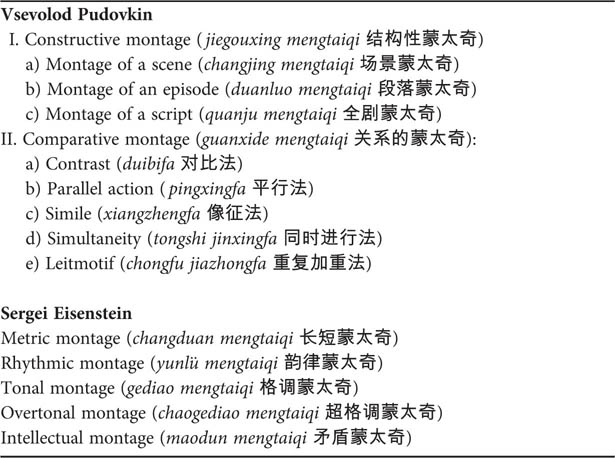

Table 3.1 Pudovkin’s and Eisenstein’s categories of montage.

3

Translating Soviet Montage

The term ‘Soviet montage’ refers to the wave of experimentation in film method that flourished in Soviet Russia in the 1920s. Its most important figures included Lev Kuleshov (the Kuleshov experiment), Sergei Eisenstein (the montage of attractions), Dziga Vertov (The Man with a Movie Camera) and Vsevolod Pudovkin (Storm Over Asia), men whose directorial work or film theory and criticism would become part of the standard canon in film studies. Soviet montage theory would become synonymous with avant-garde and modernist aesthetics, along with other early twentieth-century artistic movements like Dadaism, futurism and surrealism. Although different directors advocated different aspects of Soviet montage, all of them acknowledged film’s formal malleability: the way editorial rearrangement of shots (film negatives) allows for defamiliarisation or estrangement (остранение). For Dziga Vertov, montage allowed the camera eye (кино глаз) to perceive reality differently, creating what he called ‘film truth’ (кино правда). Sergei Eisenstein pushed the limit of film form to forcefully manipulate audience emotions through the ‘montage of attractions’, a technique that gave montage immense potential as an aesthetic experiment and as a form of propaganda and persuasion.

This chapter primarily examines the ways Eisenstein and Pudovkin were received and read in China after 1949. Rather than discounting their revolutionary allure, I look at how Eisenstein’s and Pudovkin’s different formulations of montage were accorded authority in China through the work of translation at a time when ideas branded as ‘Soviet style’ were eagerly received, sometimes with ideological modifications according to the needs of the time. Soviet montage held discreet attractions for Chinese revolutionary cinema, which was invested in provoking the senses through propaganda. In her study of Chinese opera film in the 1950s and the early 1960s, Weihong Bao has described the period’s critical debates as ‘unparalleled’: ‘Few moments in the history of Chinese film criticism have been so intensely focused on questions of form and medium’, including the ascending prominence of Soviet montage theory and publication of several major works of film theory.1

As the film term ‘montage’ underwent translation and crossed into another cinematic system, in a different temporal and spatial context, it underwent a number of linguistic and cinematic transformations. The theoretical permutations of ‘montage’ as it was translated and introduced into China beginning in the early 1930s, and the resulting film practices as Chinese film-makers continued to re-read, redefine and reinvent it after 1949, were significant developments in Chinese cinema and international film theory. These developments can reframe our understanding of the methods, forms and impact of revolutionary cinema.

In the 1930s, their sense of the revolutionary potential and allure of Soviet montage led Chinese film-makers to attach a mysterious aura to the Chinese transliteration mengtaiqi 蒙太奇, which literally means ‘veil (is) too strange’. During the later period of intense engagement with international film theory, from 1949 to 1962, Chinese film-makers would demystify the inscrutability of montage, broadening it into a synonym for film editing generally, including both Soviet montage and Hollywood continuity editing. This discursive move would allow Chinese film-makers and cultural authorities to implicitly accept, aspire to and traverse Hollywood continuity editing and Soviet montage – without openly capitulating to the ideological enemies those systems might have signified politically.

Close reading of critical discourses and selected films shows ‘montage’ being reconceived and deployed for the particular goal of cinematically constructing a collective subject. This cinematic creation was often achieved through montage that orchestrated climactic moments. The attractions that montage generated in Chinese revolutionary film were visual, aural, kinaesthetic, political and even erotic, with spectatorial implications larger than, and different from, either the ‘montage of attractions’ (монтаж аттракционов) formulated by Eisenstein or the ‘cinema of attractions’ suggested in Tom Gunning’s writings on early cinema.

Stephanie Donald and Ban Wang have discussed, respectively, the cinematic construction of a collective subject through the creation of the ‘socialist realist gaze’ and the sublimation of private desire; yet not much has been said about film method per se.2 Jason McGrath has supplemented the sublimation thesis by looking at how genre conventions of classical Hollywood heteronormative romance are deployed to facilitate sublimation. He has suggested that while fiction films during the Seventeen Years mostly follow classical Hollywood narration, they were also filled with ‘rhetorical flourishes reminiscent of early Soviet montage’.3 Those rhetorical flourishes were the result of Chinese film-makers’ longstanding efforts, beginning in the 1930s, in experimenting with and perfecting the use of montage.4 As a cinematic method that put together images from different temporal and spatial contexts, montage was deployed in Chinese revolutionary cinema to showcase the success of revolution for mass persuasion, and to evoke the memory, romance and heroics of revolution.

Although Soviet montage was no longer openly promoted once the Sino–Soviet split emerged in the mid-1950s, its attractions would be re-created by a renewed use of montage that combined continuity editing (for chronological development of plot) with Soviet montage. Both techniques served to attract, provoke and persuade spectators at the level of the senses with clarity, simplicity and forcefulness. In the hands of Chinese film-makers, montage would be taken in a new direction to create a revolutionary aesthetics that renegotiated the position of Chinese cinema vis-à-vis the world.

‘Too Strange’: Translating the Riddle of Montage

‘Montage’, as an imported foreign word, a theoretical notion and a film method, befuddled many in the Chinese film industry. The current widely accepted Chinese translation of the term ‘montage’ is in fact a transliteration (and a creative translation) that approaches the sound of the original: mengtaiqi 蒙太奇. Interestingly, this transliteration is a phonetic and semantic pun in Chinese. The first character, meng 蒙, literally means ‘veiled’ or ‘clouded’, whereas the second and the third characters, tai-qi 太奇, mean ‘too strange’, ‘too extraordinary’ or ‘too marvellous’. The transliteration creates a new meaning in Chinese that is absent in the French original – ‘veil (is) too strange’ – attaching to it a mysterious aura and an alluring sound.5

It is not entirely clear who first translated the term ‘montage’ into Chinese with such creativity and mischievousness. Even Cheng Bugao, one of China’s first directors, could not recall the origins of the translated term in his memoirs. Describing himself as one among the many directors who used to consider montage ‘magical’ (shenqi), Cheng Bugao referred to montage as a ‘riddle’ and an ‘unsolved mystery’, for which ‘no one could give a simple and clear definition’.6 A look at left-wing dramatist and director Hong Shen’s A Dictionary of Film Terms (1935), China’s first such specialised dictionary, gives us some clues to how ‘montage’ acquired its strangeness as a result of translation. The size of a coffee-table book, Hong Shen’s dictionary succinctly defined over 700 foreign film terms in Chinese, with a separate English and Chinese index at the end. Foreign (mostly English) film terms ranging from ‘movie’ (huodong yingpian) to ‘dolly shot’ (tuila jingtou) and ‘close-up’ (texie) were translated into Chinese, with the English original supplied next to the Chinese translations.

The French term ‘montage’ is introduced at the end of chapter 23, ‘The director’. ‘Montage’, conceived as a technique employed at the director’s discretion, is translated as jiegou (structure) and transliterated as mengdaqi 蒙达奇:

Mengdaqi 蒙达奇 is the transliteration of the French term montage [original in French]. Translated into English, the word means ‘mounting’ [original in English] or ‘setting’ [original in English] – more or less equivalent to ‘construction’ [original in English]. Hence, it doesn’t hurt to translate it as jiegou 结构 (structure).7

It is notable that the transliteration listed in Hong Shen’s dictionary, mengdaqi 蒙达奇 – phonetically similar to the currently accepted mengtaiqi 蒙太奇 – literally means ‘veiled (to the point of) reaching strange’, conveying the core idea of strangeness (qi) associated with montage. The transliteration mengtaiqi would gradually win over the indirect translation jiegou (through the mediation of English as the vehicular language) as the established translation of the term ‘montage’: a victory of phonetic sound over meaning. Jiegou, lacking both the appealing subtext of strangeness and an attractive sound, was too mundane to live on as a term.

The acquired strangeness and extraordinariness of the term mengtaiqi had to do with the foreignness, even untranslatability, of ‘montage’ as a newly imported theory and method in China in the early 1930s, as well as with Chinese left-wing film-makers’ fascination with the revolutionary promise of Soviet montage. The foreignness, untranslatability and lack of a Chinese equivalent for the term were apparent in the 1933 translation of Pudovkin’s The Film Director and Film Material (Кинорежиссер и киноматериал) (Dianying daoyan lun) (1926).8 Throughout their translation, left-wing screenwriters Xia Yan and Zheng Boqi rendered montage in the French original, retaining its foreign flavour and untranslatability. Nothing could better accentuate the foreignness, strangeness and untranslatability of the original term than leaving the foreign letters untranslated.

However, Xia Yan and Zheng Boqi did attach the French term montage to the Chinese adjectival and adverbial modifier de di 的地, creating a half-French and half-Chinese neologism: montage-dedi. The newly formed adverb literally embodied the linguistic encounter between languages as well as the encounter between different cinematic systems. As Lydia Liu has explained, translation is a process that takes place in ‘the zone of hypothetical equivalence’:

One does not translate between equivalents; rather, one creates tropes of equivalence in the middle zone of translation between the host and guest languages. This zone of hypothetical equivalence, which is occupied by neologistic imagination and the super-sign, becomes the very ground for change.9

The historicity of translation, and the power inequality that constitutes the work of translation, can be seen throughout the continuous effort of translating foreign film terms that circulated as cultural currency in the Chinese market in semi-colonial Shanghai in the 1910s.

Highly conscious of the peripheral position of Chinese cinema in relation to Hollywood cinema after World War I, Xia Yan and Zheng Boqi established a discourse on film-making by translating Soviet works on montage as a counterforce against the domination of Hollywood cinema. Chinese film-makers’ enthusiastic response to Soviet montage coincided with the left-wing cinema movement, whose representatives perceived Soviet cinema as offering a new path for Chinese cinema. Xia Yan’s and Zheng Boqi’s translation of Pudovkin was one of two path-breaking events marking the beginning of Soviet influence on Chinese cinema; the other was the 1931 public screening of Pudovkin’s 1928 film, Storm Over Asia (Потомок Чингис-хана).10 Xia Yan described Soviet cinema as a ‘progressive’ and ‘socialist’ cinema that pointed China to ‘the path of realism’.11 Beginning in 1932, after the restoration of relations between the Nationalist Party and the Soviet Union, there were further efforts to introduce the Chinese audience to Soviet directors like Eisenstein and Pudovkin. The 1930s also witnessed a surge in film reviews and articles about the attractions of Soviet cinema, its pedagogical value and cinematic novelty. It is not surprising that under such circumstances, news of Soviet montage as a revolutionary idea and a formal experiment began to circulate widely, with the term gradually acquiring its unusual attractions. From montage to mengdaqi 蒙达奇 and jiegou 结构, and the eventual phonetic and semantic twist to mengtaiqi 蒙太奇, the birth of a new phonetic phrase conveying a newly acquired strangeness helped set the stage for a number of important Chinese cinematic innovations.

The Revolutionary Allure of Soviet Directors: Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin

The French word montage simply means ‘editing’ in a general sense; that is, how shots are put together to make up a film. Chinese translators, left-wing film-makers and critics in the 1930s and 1940s, however, were primarily interested in Soviet montage as a formal experiment in the strict sense. In a series of articles published in the early 1940s, Shen Fengwei, a Chinese film critic, selectively delineated various categories of montage formulated by Eisenstein and Pudovkin (Table 3.1).12

Table 3.1 Pudovkin’s and Eisenstein’s categories of montage.

Shen yoked Eisenstein and Pudovkin as representatives of Soviet montage at the expense of further discussion of the disagreements between the two directors:

We know that montage originated in France, but it is the most developed in Russia […] Some people describe montage as the ‘Russian editing style’ (eguoshi jianjie). Obviously, this description is not correct. Montage is not merely editing. Nevertheless, the term ‘Russian editing style’ draws our attention to Russia and its two directors – Pudovkin and Eisenstein.13

Shen makes two intentional choices here. First, although montage, as a term, is said to have originated in France, Shen associates ‘montage’ as a specialised film method with Russia, where it blossomed.14 Second, Eisenstein and Pudovkin are singled out as its masters. Amy Sargeant has suggested two reasons why, despite their differences, Pudovkin and Eisenstein have often been brought together under the term ‘Soviet montage’: Soviet silent films continued to be popular among foreign audiences well into the sound period because of their ‘revolutionary’ aura, and ‘[a]lthough Kuleshov, Pudovkin and Eisenstein elect to practice montage differently, true to type as a Soviet “school”, in the 1920s at least, they agree that editing is the technique by which film distinguishes itself.’15 The formally and politically revolutionary aura of Soviet montage explains why Eisenstein and Pudovkin were coupled by Shen, who selectively introduced montage from the Soviet Union, the birthplace of revolution, to the Chinese public.

Given the canonical place that Eisenstein’s and Pudovkin’s formulations of montage occupied in Chinese reception of Soviet montage, Eisenstein’s phrase, ‘montage of attractions’, and Pudovkin’s ‘montage as series’, provide a point of departure and terminological framework for this chapter.16 Eisenstein’s montage of attractions consists of rapid alternation between sets of shots that are independent of one another, generating collision and giving rise to an idea not necessarily present in the shots at the denotative level; and collision of shots as a result of fast cutting and unusual camera angles, defamiliarising norms of time and space. Pudovkin’s montage as series refers to the unrolling of an event through a series of fragments (a narrative following a given course with maximum continuity and minimal disruptions from non-diegetic inserts).

Pudovkin’s comparative montage (contrast, parallel actions, simile, simultaneity and leitmotif) was a refinement of D. W. Griffith’s basic editing, one that achieved narrative economy and diegetic contiguity. The five kinds of comparative montage categorised by Pudovkin in ‘The Film Script (The Theory of the Script)’ would be reiterated by Shen and other film critics beginning in the 1940s and throughout the 1950s:17

(1)Contrast (контраст): To illustrate how a contrast can force viewers to make comparisons between two activities, Pudovkin offered the example of a contrasting comparison between the plight of a starving man and the senseless gluttony of a rich man, established by individual shots within scenes.

(2)Parallel action (параллелизм): Pudovkin used the example of the impending execution of a strike leader and his drunken boss looking at his watch in a restaurant to illustrate how ‘two thematically unconnected actions are linked together and proceed in parallel.’18

(3)Simile (уподобление): A simile conveys an abstract concept without intertitles. For instance, in the final scene of Strike (Eisenstein, 1925), a series of shots that alternate between the shooting down of the workers and the slaughtering of a bull convey brutality with vividness and intensity.

(4)Simultaneity (одновременность): To illustrate the ‘simultaneous rapid development of two actions, with the outcome of one depending on the other’, Pudovkin used the example of the ending of D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), composed of a series of shots rapidly alternating between the impending execution of a worker and his wife trying to catch up with the governor’s train in order to obtain a pardon for him.19

(5)Leitmotif (напоминание): A device of reiteration that emphasises a main idea of the script: for instance, the recurring shot of a bell in the Church in an anti-religious script to convey the hypocrisy of the Church.

It is notable that Pudovkin’s categorisation of comparative montage was favoured over Eisenstein’s montage methods, which were deemed ‘esoteric’: ‘Practically speaking, Eisenstein’s theory is too broad and esoteric. It is difficult to apply and comprehend.’20 Taking into account Eisenstein’s labelling as a formalist in the Soviet Union by the 1930s, Chinese film critics who appreciated Eisenstein’s film art began to re-evaluate his films with a critical eye. Their positive attitude towards Pudovkin, sometimes referred to as the ‘Russian Griffith’ (because of Pudovkin’s explicit acknowledgement of D. W. Griffith’s editing style, upon which he developed his montage methods), is not surprising, given the popularity of Hollywood movies in semi-colonial Shanghai beginning in the 1910s.21 By the 1930s, Republican Shanghai cinema had mastered the close-up, crosscutting and comparative montage refined by Griffith (in the classical continuity system), Pudovkin and others, and had creatively put those methods to use.22

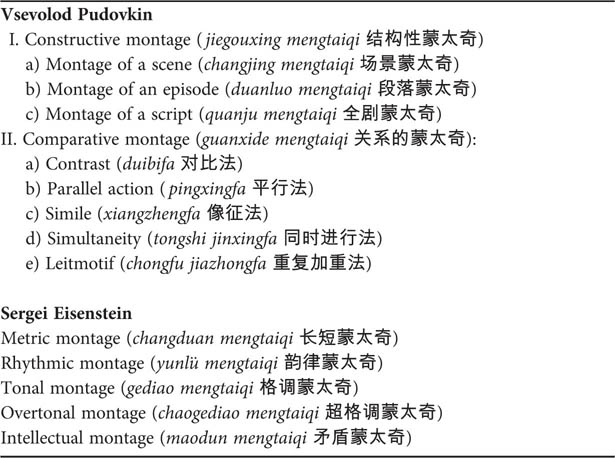

For example, the left-wing film-maker Cai Chusheng mobilised montage for political criticism in The New Woman (1934). While the story of The New Woman largely adheres to classical Hollywood narration as the tragedy of the protagonist Wei Ming unfolds, there are specific moments when the use of montage intervenes in the narrative flow and heightens its affective intensity. In the scene where Wei Ming dances with her suitor, for example, a contrast montage sequence juxtaposes close-up shots of dancing feet with shots of the labourers’ feet, framed by a clock, establishing parallel actions in a shared temporality (Figure 3.1). The combination of similarity in form (the circular frame) and contrast in meaning points to class contradictions.23 Here, montage creates a third meaning through the collision of two images framed by a clock.

Figure 3.1 A contrast montage sequence that establishes parallel actions in The New Woman (1934).

The contrast montage sequence is later followed by a split-screen montage sequence (montage within a frame), in which Cai Chusheng unified temporally and spatially disconnected images, depicting teacher and students singing a revolutionary song on one corner of the screen while the rest of the screen depicts the colonial architecture on the Bund in Shanghai (Figure 3.2). Through the use of the split screen, the two unrelated events are linked together and proceed in parallel. As well as paralleling the actions, the split-screen montage sequence most importantly establishes a contrast through the singing of a revolutionary song against the backdrop of semi-colonial Shanghai. At its inception in Soviet Russia, sound was conceived by both Eisenstein and Pudovkin as a distraction from the visual and thus an inhibitor of the aesthetic and ideological functions of montage; however, in The New Woman, situated on the threshold of the sound era in Chinese cinema, sound elevates the affective intensity of montage with clarity and forcefulness.24

Figure 3.2 A split-screen montage sequence that establishes contrast as well as parallel actions.

Despite the versatility of Chinese film-makers in creatively combining classical Hollywood narration with Soviet montage, Shen nonetheless perceived shortcomings relative to foreign (primarily Western) cinematic counterparts: ‘What is it that we lack? The reason why we are not able to separate film from stage drama is that we are not using montage well enough.’25 Here, montage is conceived as a cinematic means of expression and a cinematic currency with the potential to enable Chinese cinema to overcome its deficiencies. Yet rather than calling for a wholesale subscription to Soviet montage, Shen advocated selective theoretical and practical adoption and modification of Soviet montage: ‘If possible, we should improve and supplement montage in terms of theory or technique.’26 Importantly, Shen’s statement is not concerned with authenticity, originality or fidelity to certain conceptions of montage. This pragmatic attitude, a first step towards unveiling the mystery of montage, was accompanied by his call for Chinese cinema to innovate: ‘Now that film is an independent art, we should walk a new path. This new path may be “montage”, or maybe not. Nonetheless, a new path is absolutely necessary.’27 Shen’s attempt to move past the enigma of montage was to be echoed by later film-makers, who took up the task of reinventing montage after 1949.

Reinventing Montage: The Rhetoric of Simplicity

As Bao has pointed out, montage, understood as a key mode of cinematic expression, was ‘part and parcel of the institutionalization of cinema, when theories of montage and realism gained currency just as the film industry in the People’s Republic was solidifying’.28 The eventful year of 1953 witnessed the institution of the First Five-Year Plan, under which film theory was considered one of the three major targets of ‘film construction’. Socialist realism, officially endorsed by Zhou Yang as ‘the road of advance for Chinese literature’, would become the banner under which study of Soviet film theories and techniques took place.29 That same year, a Chinese study group of 20 film artists and technicians travelled to Moscow to learn about various practices in the Soviet film industry for a year, and Eisenstein’s The Film Sense (Dianying yishu sijiang) was translated into Chinese.30

By the second half of the 1950s, discussions of montage had become theoretically sophisticated, resulting in several major translations and anthologies on Soviet montage as well as publications about montage, editing and the specificity of the filmic medium. For instance, Shi Dongshan’s Dianying yishu zai biaoxian xingshi shang de jige tedian (Several Characteristics of the Cinematic Means of Expression) (1958), Zhang Junxiang’s Guanyu dianying de teshu biaoxian shouduan (On the Specific Means of Cinematic Expression) (1959) and Xia Yan’s 1958 speech on screenwriting at the Beijing Film Academy (later published in 1978 as Xie dianying juben de jige wenti) all highlighted film’s artistic specificity and construed montage as a fundamental means of cinematic expression.31 Publications on montage continued to flourish in the early 1960s: Eisenstein’s and Pudovkin’s selected writings were anthologised in two volumes in 1962, concurrent with the publication of Ji Zhifeng’s Mengtaiqi jiqiao qiantan (A Brief Introduction to Montage Techniques).32 Briefly outlined here, the burgeoning publications on film theory and practice in the 1950s and 1960s constituted a sophisticated film discourse, notwithstanding the rhetoric of simplicity often used to characterise cinematic production during the Seventeen Years.

The reinvention of montage was in fact heavily invested in the rhetoric of simplicity, in accordance with the talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art in 1942 in which Mao had explicitly advocated popularisation over raising artistic standards. In the 1950s, Xia Yan highlighted accessibility and simplicity as guiding principles to understanding and practising montage: ‘Montage in Chinese film can be more accessible (pingyi), from the perspective of the masses (qunzhong guandian). Our principle should be accessibility for the majority.’33 Similarly, Shi Dongshan considered comprehensibility a priority in film editing: ‘The basic technique of editing is, first, striving for comprehensibility for the audience. Second, maximising the fundamental strength of cinema.’34 Yet though accessibility, simplicity and comprehensibility were often emphasised in Chinese discourse on montage, one must keep in mind that the rhetoric of simplicity is itself artistically sophisticated. The reinvention of montage operated on a complex social and aesthetic agenda with deep concerns for spectatorship. Chinese film-makers, working under the auspices of the state, sought to create for its targeted audience a revolutionary aesthetics: simultaneously accessible and attractive, pedagogical and pleasurable to the eye. Rather than taking the rhetoric of simplicity at face value and thereby labelling Chinese revolutionary film as a simple form of mass propaganda, we can and should reconceive it as a cinema that strove to be accessible, pedagogical and popular.

The first step by which Chinese film-makers and cultural authorities redefined montage was to debunk its mystery by keeping a theoretical distance from Soviet directors. This strategic discursive move was in part necessitated by international politics. Chinese film-makers and critics became highly conscious of the dangers of formalism and aestheticism from the mid-1950s onwards, as the Sino–Soviet split emerged, followed by the Hundred Flowers Campaign and the Anti-Rightist Campaign, opening up debates on the nationalisation of cinema. As a result of these shifts, Chinese film-makers gradually distanced themselves from the Soviet directors they had embraced in previous decades. The prefaces and postscripts to anthologies served as a framing discourse and regulatory force to contain, repackage and relabel Soviet montage theories that continued to circulate in the PRC after the Sino–Soviet split. For instance, Eisenstein and even the less esoteric Pudovkin were perceived by Zhang Junxiang as masters who had followed the wrong path: ‘Today, nobody is obsessed with form or considers the organisation of shots as the only method of film-making. Nonetheless, there was a period when masters like Eisenstein and Pudovkin followed the wrong path.’35 Zhang rejected earlier exaggerations of the artistic value of montage in sayings such as ‘an individual shot is lifeless’, ‘film is born on the editing table’ and ‘the director’s materials are film negatives’.36 Similarly, Qi Zhou, the translator of Eisenstein’s The Film Sense, described Eisenstein as a genius director who nonetheless ‘gave in to the temptations of formalism’ and ‘lost the connexion with life’, reminding his Chinese readers of the need to carefully ‘select’ and ‘digest’ what was beneficial to them.37 The official policy of ‘leaning to one side’ was revisited as the Sino–Soviet split emerged, resulting in a more critical reception of Soviet masterpieces. This more selective approach to Eisenstein’s and Pudovkin’s works reveals the contingency of their original reception and the various ways in which they were claimed, used and revised by the work of translation and the canonisation of film theories.

The second step by which Chinese film-makers and cultural authorities reinvented montage was to redefine the term’s scope to encompass all film editing methods, thus returning to the original meaning of the French word. This discursive move gave Chinese film-makers the freedom to creatively manoeuvre between Hollywood continuity editing and Soviet montage without explicitly endorsing or wholly adopting either.

Shi Dongshan, one of the most prominent Chinese film-makers who contributed to the rethinking of montage, explained the two approaches to montage in the history of Chinese cinema. The first approach considered montage ‘mysterious’ and ‘incomprehensible’, whereas the second approach took a ‘narrow view’, emphasising the contrastive effects of montage that, according to Shi Dongshan, were the hallmark of Eisenstein’s montage of attractions.38 Shi Dongshan rejected the narrow approach, insisting that continuity and contrast should be united rather than oppositional. He defined lianxu de gouchengfa (continuity editing) as an editing method that broke down shots according to the development of plot; duili de gouchengfa (contrastive editing) included Eisenstein’s montage of attractions, which juxtaposed shots depicting one phenomenon with non-diegetic inserts depicting another to produce contrast, conflict and collision that stimulate the audience’s thinking. Shi Dongshan pointed to the mass slaughter sequence in Eisenstein’s Strike (1925), which juxtaposes non-diegetic inserts of a butchered bull and shots of the slaughtered masses, as an example of contrastive editing (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3 Shi Dongshan considered the mass slaughter sequence in Eisenstein’s Strike (1925) an example of contrastive editing.

Shi Dongshan went on to say that defining montage narrowly, confining it to contrastive editing, would be the same as ‘adopting the view and tone of formalism’.39 Montage should include ‘all editing techniques, whether they belong to continuity editing or contrastive editing’,40 especially since Soviet cinema, like many other cinemas, ‘uses continuity as the basic editing method’.41

Like Shi Dongshan, Xia Yan favoured continuity for clarity and comprehensibility. An outstanding montage, according to Xia Yan, was ‘in accord with reason, sensibility, actual life and visual logic’.42 Xia Yan highlighted the complications of luan (chaos) and tiao (jumps) – chaotic narration, chaotic plot, chaotic frames and chaotic directions – in the use of montage in Chinese cinema. He looked to Pudovkin for theoretical guidance, offering ‘a good quote from Pudovkin: “Generally speaking, the basic demand of film is to direct the audience’s attention to the chronological development of plot.”’43 Xia Yan’s emphasis on chronological narration and continuity is best expressed in his explanation of the term fenjingtou juben (shooting script): ‘In English, a shooting script is called “continuity” [original in English]. The word comes from the verb “continue”, and the meaning of “continue” includes “to connect” and “to go on”.’44 In favouring clarity, chronology and continuity, Shi Dongshan and Xia Yan implicitly leant towards Hollywood continuity editing for the sake of accessibility and comprehensibility by a wide audience.

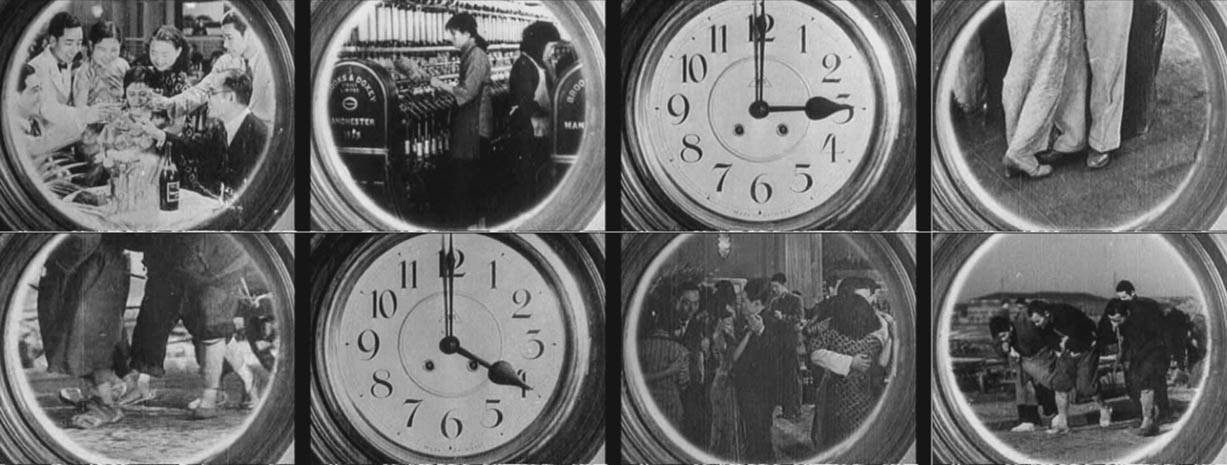

To reinvent montage as a general term for all film editing methods, Chinese film-makers and critics such as Ji Zhifeng, Shi Dongshan, Xia Yan and Zhang Junxiang redefined its scope to include four aspects of film editing: the structure and composition of individual frames, the editing of shots, sound (as constitutive of montage), and montage as a method that creates continuity and contrast. Ji Zhifeng redefined and re-codified montage as a general term for all film editing methods in an illustrated reader-friendly manual, Mengtaiqi jiqiao qiantan (A Brief Introduction to Montage Techniques) (1962) (Table 3.2). In the introduction, Ji Zhifeng, like his counterparts Shi Dongshan and Xia Yan, broadened the scope of montage to include ‘all the techniques related to the arrangement of shots and sound composition’, though the ‘editing of shots’ is ‘the foundation of montage’.45 Chinese film-makers’ mid-century redefinition of montage as a synonym for ‘film editing methods’ facilitated the creative adaptation of Hollywood and Soviet methods in creating Chinese revolutionary cinema.

Table 3.2 Ji Zhifeng’s Mengtaiqi jiqiao qiantan (A Brief Introduction to Montage Techniques) (1962) is divided into nine sections, which together establish montage as a general term for all editing methods.

Shot Division as Re-Creation

Chinese film-makers like Shi Dongshan began by defining their terms, revisiting the basic principles of shot division in montage: ‘What is called “editing” (jianjie) actually belongs to the category of shot division (fen jingtou) (there are many people who are confused by the concept). That is because the editing of shots in narrative films is determined by shot division.’46 Shot division and the writing of a shooting script, described by Cheng Bugao as a ‘re-creation’ (zai chuangzuo), were developed into a specialised and collaborative method during the Seventeen Years, when all films produced were based on shooting scripts written after multiple discussions and revisions.47 Shot division was the second step in the process of film production, right after the writing of a literary script (wenxue juben).

Cheng Bugao’s word, ‘re-creation’, described shot division as the reinvention of a literary script in its filmic form, one that required a re-conception of the script in terms of shot distance, camera angle, length of shots, division of segments, pausing and sound. In short, shot division and the writing of a shooting script involved rethinking film as a visual medium. Shen Fengwei, writing in the 1940s, thought Chinese cinema ‘lacked’ this specificity of medium:

I used to ask a few foreign experts what they thought of Chinese film. They all said that ‘Chinese film seems too close to stage drama (wutaiju).’ Such an answer is earnest, but it is also a euphemism. They may as well say that Chinese film lacks the specificity of the filmic medium.48

Zhang Junxiang’s redefinition conceived montage as the grammar of film, a grammar that enabled Chinese cinema to overcome a ‘lack of actions, excessive dialogue and oral narration, and [overly] complex structure’.49

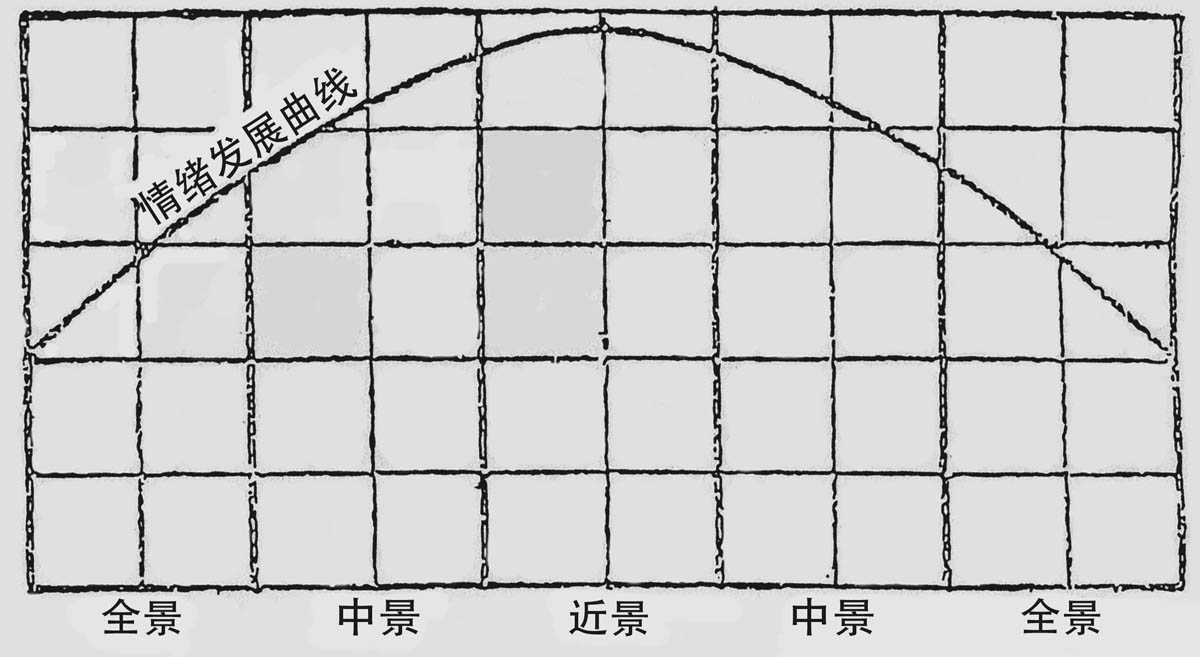

In Mengtaiqi jiqiao qiantan, Ji Zhifeng opened by discussing shot distance and camera angle. He illustrated the correlation between shot distance and emotional intensity as a curve: the shorter the shot distance, the higher the emotional intensity (Figure 3.4). According to Ji, a close-up would yield more intense emotions and facilitate audience identification with the characters on screen, an explanation that echoed Pudovkin’s appraisal of Griffith’s refinement of the close-up as a crucial component of montage. Correlating shot distance and emotional intensity would become the basis for engineering climactic moments in Chinese revolutionary film.

Figure 3.4 Ji Zhifeng illustrated the correlation between shot distance and emotional intensity as a curve, which he called the curve of ‘emotional development’. The shorter the shot distance, the higher the emotional intensity. The X-axis labels read (from left to right): long shot, medium shot, medium close-up shot, medium shot and long shot. Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

Ji Zhifeng also explained that camera angle worked hand-in-hand with shot distance to create the visual image (shijue xingxiang) of a fictional character. High-angle shots were typically used to depict villains and class enemies, whereas low-angle shots were typically used to depict heroes and heroines so that they appear larger than life. For example, the condemned Wang Shiren in The White-Haired Girl (Wang Bin and Shui Hua, 1950) is depicted in a high-angle shot that visually belittles the moral villain and class enemy kneeling on the ground. In contrast, the eponymous heroic female soldier in Zhao Yiman (Sha Meng, 1950) is glorified with a low-angle shot. In The Urgent Letter (Shi Hui, 1954), even a child soldier is depicted in a low-angle shot, visually enlarging the child’s physical stature against the vast landscape.

Attractions

Despite the discursive move away from Soviet montage, its discreet attractions persisted in subtle forms in Chinese revolutionary film. Although contemporary critics felt the need to broaden the meaning of montage from 1949 onwards, they nonetheless retained the term. And indeed, montage can be seen in Chinese revolutionary cinema, recognised as a highly self-conscious cinematic technique that creates attractions at climactic moments. Those visual, aural, kinaesthetic, political and even erotic attractions facilitated audience identification with a collective revolutionary subject and the Party.

My use of the word ‘attractions’ intentionally establishes a dialogue with Eisenstein’s ‘montage of attractions’ and the ‘cinema of attractions’ analysed by Tom Gunning in his writings on early cinema. Gunning’s term helps us understand the exhibitionist quality of early cinema, before the integration of narrative from 1906 onwards. According to Gunning, the act of showing and exhibiting (such as the recurring look at the camera by actors) ‘incites visual curiosity’ and ‘supplies pleasure’ to an audience fascinated by the potential of the new medium.50 Gunning, too, takes the term ‘attractions’ from Eisenstein, in his case because of the latter’s emphasis on direct stimulation rather than diegetic absorption.

In the context of Chinese revolutionary cinema, montage sequences accompanied by revolutionary songs functioned as direct stimulation integrated into diegetic absorption – for instance, in the way sound augments the affective intensity of montage in The New Woman. Montage sequences of this sort heightened dramatic, emotional and ideological persuasion, creating experiential moments of sight and sound in the midst of the cinematic narrative that facilitate diegetic absorption. This is one of the primary attractions of Chinese revolutionary cinema, which was premised on direct stimulus and persuasion rather than the intellectual leap generated by Eisenstein’s montage of attractions.

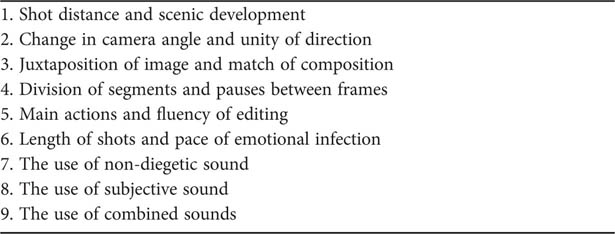

Montage and Revolutionary Songs

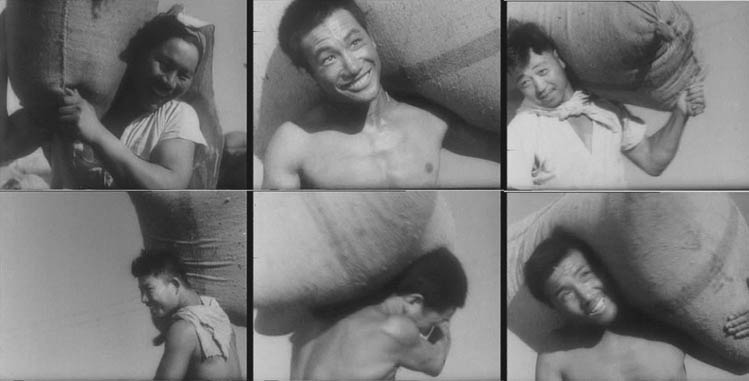

In the early socialist revolutionary film Gate Number Six (Lü Ban, 1952), a film about the success of a workers’ strike, fast cutting, combined with a montage sequence accompanied by revolutionary song, generates a visually and aurally provocative kinaesthetic rhythm. The montage sequence is characterised by quick editing with manifold shot ranges and camera positions that defamiliarise, exhibit and glorify physical labour as a joyous collective endeavour (Figure 3.5). As a result of the rapid succession of individual smiling faces and bodies in medium shots, spectators are stitched into the diegesis with little choice in what they see. As David Bordwell has suggested in the context of historical–materialist narration: ‘Rapid editing is the most self-conscious effort of the rhetorical narration to control the pace of hypothesis formation.’51 Combined with the forceful rhythm generated by the theme song, fast cutting maximises the narrative economy and diegetic contiguity central to Pudovkin’s ‘montage as series’ (the unrolling of an event through a series of fragments) and creates a strong sense of kinaesthetic motion. The orchestration of visual and sound effects through the use of montage creates the impression that, in the words of McGrath, ‘communists have more fun’ – it is ‘precisely through collective action that the individual finds the greatest meaning and fulfillment’.52 The combination of fast cutting and revolutionary song in Gate Number Six’s montage sequence attracts spectators at the level of their senses, glorifying collective labour in its anonymous mass heroes.

Figure 3.5 Fast cutting is combined with a revolutionary song in a montage sequence in Gate Number Six (1952).

Chinese revolutionary cinema also made use of Hollywood-style montage sequences to condense the passage of time into a succession of images connected by superimpositions, dissolves and fades. These montage sequences, often accompanied by songs, function as cinematic punctuations, transitions and conclusions. For instance, the montage sequence in the climactic ending of the early socialist revolutionary film The White-Haired Girl, accompanied by a revolutionary song, celebrates the destruction of the villain Wang Shiren’s property, the reunion of the couple and the change of seasons in a concise and rhetorically compelling manner.

Comparative Montage and ‘Subjectified Sound’: The Case of Nie Er

Use of comparative montage and sound matured in the late 1950s, as exemplified by the ending of Nie Er (Zheng Junli, 1959), in which crowd scenes and various kinds of comparative montage – contrast, parallel action, simile and leitmotif – coexist in the film’s final moments, culminating in the climax of the song that would become the PRC national anthem. The highly complex montage sequence combines various modes of montage and distorts temporal–spatial order to unify actions in various times and spaces (Figure 3.6). By crosscutting, the sequence creates an illusion that all critical events – long lines of suffering labourers at the prison gate, a mass demonstration in front of the government office, the Japanese army’s execution of Chinese patriots, the capture of Luding Bridge by the communists, a peasant field revolt, and Nie Er at his desk composing ‘March of the Volunteers’ in a flash of inspiration – take place in parallel. From the song’s germination to its completion, the sequence reinforces montage’s capacity to defamiliarise temporal–spatial norms and reconstruct a novel sense of narrative time and space. Pudovkin’s ‘montage as series’ – the unrolling of an event through a series of fragments – was reinvented in the hands of director Zheng Junli, who put together fragments of multiple events to condense and speed up time and re-create the kinaesthetic motion of revolutionary struggle.

Figure 3.6 A montage sequence in Nie Er (1959) that distorts temporal–spatial order to re-create a historical continuity that represents revolutionary struggle.

Nie Er’s rhetorical combination of images taken from the diegetic world not only functions as typical Hollywood-style montage flashbacks, but also ‘allows the narration to present images initially designed to denote fabula information, and then to recall them for connotative purposes’.53 The recurring images of the mass demonstration, the suffering labourers and the heroine Zheng Leidian are reiterated in this sequence to constitute leitmotifs for the film as a whole. The first half of the sequence, depicting suffering and humiliation, is contrasted with the latter half of the sequence, depicting victory. A simile is established between the flare in the field, where the peasants revolt, and the fire of inspiration that Nie Er ignites as he writes at his desk in front of a burning candle, composing the lyrics in ‘March of the Volunteers’: ‘brave the enemy’s fire, march on’. Multiple coexisting modes of comparative montage strengthen the overall ideological and aesthetic goal, defining Nie Er as a revolutionary hero on the cultural front, working simultaneously with the collective, who fight on the military front and heroically sacrifice themselves.

Also within this sequence, the enlargement of certain details such as inserts of the music sheets and close-up shots of Nie Er direct viewers’ attention to the subjectivity and creative activity of the composer. According to Ji, ‘subjectified sound’ (zhuguanhua yin) referred to the sounds (both diegetic and non-diegetic) generated to convey the subjectivity of revolutionary heroes and heroines. ‘Subjectified sound’ was often combined with montage and ‘subjective shots’ (zhuguan jingtou) of positive characters (zhengmian renwu) to ‘directly convey the psychological actions of characters’.54 The alternation and succession of images in Nie Er’s montage sequence, accompanied by the revolutionary song, create variations of tempo and a constant shifting of emphasis from Nie Er (the hero through whom the audience hears the song) to the fighting army and the collective subject of the masses. The use of ‘subjectified sound’, orchestrated by montage, produces the voice of the collective. As Zhang Junxiang suggested: ‘When the same sound crosses over to a scene in a different time and space but of the same nature, an emphasising effect is created.’55 The musical continuation does not necessarily contradict the content of individual frames; instead it enhances the emotive and persuasive power of individual frames, accumulating through the end of the montage sequence, which culminates in the final completion of the song. The montage sequence, with the aid of revolutionary song, establishes continuity despite and because of its distortion of temporal–spatial order.

Without excessive reliance on speech, the use of multiple modes of comparative montage combined with sound allowed director Zheng Junli to cinematically depict a complex network of actions, to construct a historical narrative, and to create a distinct image of the hero for the audience to identify with. The film combined the use of various kinds of comparative montage, accompanied by sound, to convey its revolutionary message with a high degree of conciseness and clarity, ruling out any possibilities for narrative, visual and aural ambiguity.

Internal Montage: Superimposition, Memory-Making and Leitmotif

Chinese film-makers also employed superimposition, described by Ji Zhifeng as an ‘internal montage’ (that is, montage within a frame), to arouse revolutionary memories, which function as leitmotifs within filmic narratives. Superimposition depicts two images from different times and spaces through double exposure. In the hands of Chinese directors it became a highly malleable rhetorical device for the purpose of memory-making.

In Stage Sisters (Xie Jin, 1965), the literary character Xianglin Sao, emblematic of feudal oppression, becomes a leitmotif replicated and cited by montage at a turning point in the film when Chunhua attends an exhibition. The scene begins with a close-up shot of Jiang Bo and Chunhua looking at a woodblock print of Xianglin Sao as Jiang educates Chunhua about Xianglin Sao’s misfortune: ‘She [Xianglin Sao] was widowed twice and people shunned her as a woman who brings misfortune.’ Succeeding this shot is a frontal close-up shot of Chunhua. The camera then slowly tracks into an extreme close-up shot of Chunhua’s teary eyes as she is overwhelmed with emotions. At this critical moment, extra-diegetic music is played simultaneously with a cut to a close-up shot of Xianglin Sao’s face. As the camera tracks in, Xianglin Sao’s face begins to fade, superimposed with Little Chunhua’s face (Figure 3.7). At this point, the extra-diegetic music reaches its climax as the sequence cuts to another extreme frontal close-up shot of Chunhua in tears. Twenty seconds of this 30-second sequence are taken up by Chunhua’s emotional absorption with Xianglin Sao, visualised in a series of alternating close-up shots of their faces. This montage sequence constitutes the climactic moment of the film, in which Chunhua begins to understand the suffering of peasant women as a collective. Xianglin Sao’s highly malleable cinematic image, superimposed with the image of Little Chunhua, constitutes a leitmotif that produces revolutionary memory for mass persuasion, a role it plays within and beyond Stage Sisters: Xianglin Sao, a feudal icon that appeared in multiple media, was repeatedly replicated and cited by montage. This type of repetition and citation through the use of leitmotif indicates the immense rhetorical potential of montage as a highly condensed cinematic language.

Figure 3.7 The use of internal montage in Stage Sisters (1965).

Empty Shots and the Relay of Gazes

The orchestration of the relay of gazes through montage constitutes one of the most signatory moments of Chinese revolutionary cinema. Stephanie Donald suggests the term ‘socialist realist gaze’ as a way to understand the cinematic convention used to evoke ‘the romance of revolution and a heroic future’.56 The socialist realist gaze regards an off-screen space rather than a defined diegetic object, signalling a leader’s political consciousness. According to Donald, the socialist realist gaze ‘needs to be shared by the characters and the audience’ in a moment of ‘ecstatic communion’.57

I suggest that the socialist realist gaze was prefigured by the cinematic relay of gazes between lead characters and supporting characters. The relay of gazes was often punctuated by empty shots, which were eventually displaced and replaced by non-diegetic inserts such as Party symbols as components of montage. The collective subject was constructed cinematically by relayed gazes in montage sequences, and the viewing subject was implicated in its visual logic.

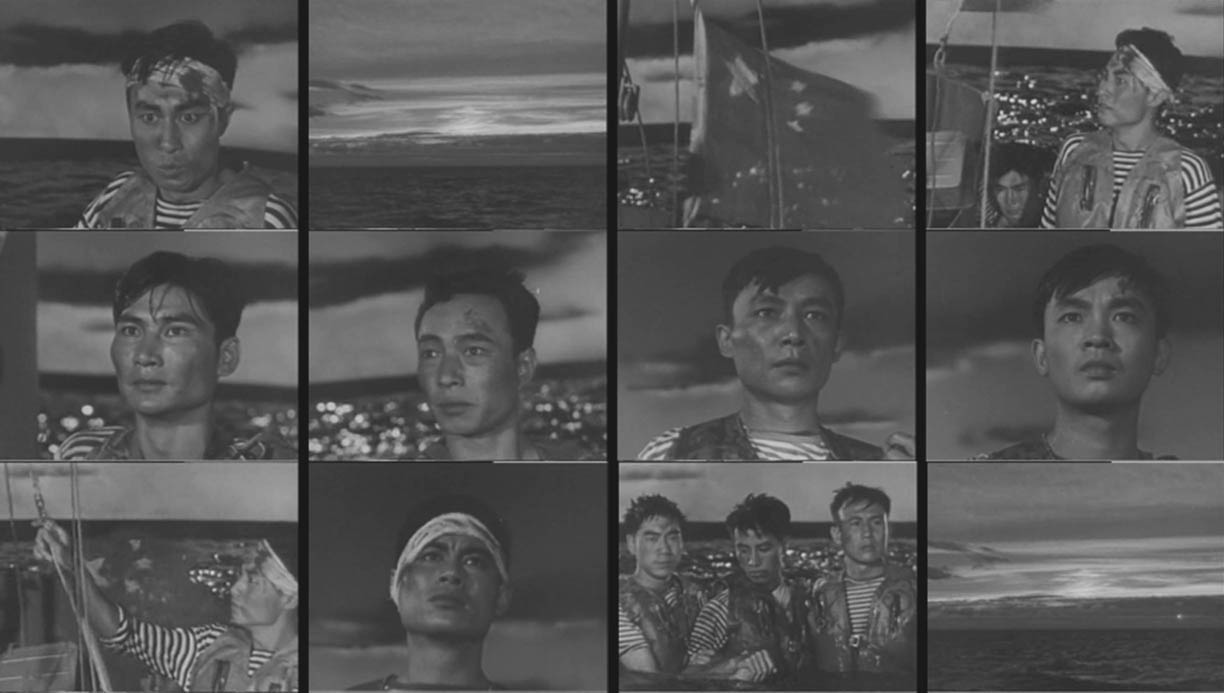

A precursor to this relaying of gazes can be seen in Pudovkin’s montage sequence in Storm Over Asia (1928), where a crowd of Mongols looks with rapture at a precious fox fur. To arouse the audience’s curiosity, Pudovkin joins together numerous close-up shots of the Mongols, whose gazes are all directed to an off-screen space, presumably the fur’s location (Figure 3.8). Variations in shot distance, camera angle and composition create an aestheticised effect and a pace that intensifies audience curiosity. Pudovkin’s ‘montage as series’ relays the Mongols’ gazes in succession, one after another, and hence directs audience attention to the fox fur, the sale of which drives the narration and the ensuing conflict forward.

Figure 3.8 Relay of gazes in a montage sequence in Pudovkin’s Storm Over Asia (1928).

The relay of gazes between characters can be seen in the final moments of the early socialist revolutionary film Zhao Yiman (Sha Meng, 1950). When the heroine Zhao Yiman is about to be executed, there is a relay of gazes from the lead character to the supporting characters to the passionate onlookers behind the prison bars. The relay begins with a medium shot of Zhao looking to an off-screen space as she shouts, ‘Long live the Communist Party!’ followed by two medium close-up shots of supporting characters looking at an off-screen but defined diegetic object, Zhao herself, behind the prison bars. Their gazes are then relayed to the sympathetic onlookers, also gazing into an off-screen space (presumably where Zhao is), in three consecutive medium close-up shots. The relay of gazes then returns to the fearless Zhao, once again looking towards an off-screen space, followed by a close-up shot of a supporting character. The film’s final shot is a medium close-up of Zhao, looking towards the horizon as she fearlessly marches ahead (Figure 3.9).

Figure 3.9 Relay of gazes from the lead character to supporting characters to passionate onlookers in a montage sequence in Zhao Yiman (1950).

The relay of gazes from Zhao to onlookers and back to Zhao is rhythmically punctuated by montage, relaying in succession a series of static gazes using the eyeline match, a type of cut central to the continuity editing system. The remarkable frontality of the gazes looking up invites and solicits the audience to look up and identify with the collective revolutionary subject, headed by Zhao, in a moment of solidarity. Positioned as the camera’s eye, the spectator performs the act of filling in the blanks and produces for him/herself a third meaning: the fearless Zhao inspires her comrades to become fearless revolutionaries. The relay of gazes freezes the narrative, elevating it to a higher level of emotional intensity. Spectators are drawn into, and implicated in, the chain of gazes, creating an effect in which ‘the gaze of the camera, the spectator and the cinematic subject are ideally brought together in a visual logic.’58 The relay of gazes orchestrated by montage creates this visual logic, by which a collective subject is constructed cinematically.

Figure 3.10 Relay of gazes and empty shots in a montage sequence in Sea Hawk (1959).

In the later socialist revolutionary film Sea Hawk (Yan Jizhou, 1959), there is a somewhat different handling of the relay of gazes. Sea Hawk’s relay of gazes takes on even greater clarity and forcefulness with shots of the national flag, close-ups of the individual faces of supporting characters and ‘empty shots’ (kongjingtou). In the scene in question, the hero removes the national flag from his sinking warship; his gaze is relayed to his comrades, whose gazes are projected towards an off-screen space, presumably where the national flag is sinking. The camera depicts in close-ups and low-angle shots the supporting characters’ individual faces in a succession of gazes, thereby directing audience attention to the sinking national flag off screen (Figure 3.10). Most importantly, the montage sequence is twice punctuated by empty shots that strengthen its emotional impact.

Chinese film-makers used the term ‘empty shots’ to refer to shots that function as pauses (jianxie) succeeding cinematic climaxes. Ji Zhifeng explained the need for long pauses after a film’s climax so that spectators could ‘calm their emotions’ and ‘use their imagination’ without narrative distractions.59 An empty shot generally depicts only scenery and contains no plot-related actions. It temporarily freezes the narrative and therefore achieves the purpose of pausing. In Sea Hawk’s montage sequence, each empty shot of the sun setting over the ocean lasts for eight seconds, suspending the narrative in a moment of emotional saturation. As a component of montage, these empty shots punctuate the relay of gazes towards the flag as a form of rhetorical emphasis, using silence as a form of persuasion: this particular sequence evokes a solemn mood and a sense of national unity. Empty shots, as an integral component of ‘montage as series’, do not interrupt continuity; they solicit the audience to fill in the blanks following cinematic climaxes by using their affective imagination.

Romance and Reunion

The Party gaze was also evoked in Chinese revolutionary film through reunions between heterosexual couples to which the Party is an implied witness. Romance and reunion were often conveyed by the Hollywood convention of shot/reverse-shot editing, a technique thoroughly assimilated in China by the 1960s and included in Ji Zhifeng’s definition of montage (Figure 3.11). When combined with mise-en-scène, lighting and acting, the shot/reverse-shot convention was typically employed to depict one-on-one conversations, combats and romance.

Figure 3.11 An illustration of an establishing shot and a shot/reverse shot that crosses the axis of action in Ji Zhifeng’s Mengtaiqi jiqiao qiantan (A Brief Introduction to Montage Techniques) (1962). Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

The shot/reverse-shot convention was also typical of reunion scenes in Soviet war films like The Fall of Berlin (Mikheil Chiaureli, 1949), which was screened regularly in China throughout the 1950s and warmly embraced by Chinese audiences. The film’s climax, in which a couple is reunited after long years of wartime separation, is conveyed through a series of shot/reverse shots and facial close-ups, all witnessed by Stalin (Figure 3.12). The couple’s kisses and physical embrace are not discouraged, but openly acknowledged by the leader: victory in war allows reunion with loved ones, the motherland and the Party. The film’s happy romantic and personal ending does not jeopardise Stalin’s status as leader. Rather, Stalin’s presence heightens the import of the romantic reunion.

Figure 3.12 The use of shot/reverse shot to orchestrate kisses and physical embrace in a reunion witnessed by Stalin in The Fall of Berlin (1949).

In Sea Hawk, the climactic ending is also a reunion sequence. The reunion takes place on the ocean, using various camera set-ups to avoid physical intimacy and create an alignment of gazes that would otherwise be produced by the shot/reverse-shot convention. In contrast to The Fall of Berlin, the relay of gazes in Sea Hawk, from the heroine to the hero and his comrades and back to the heroine, point to an off-screen space with a defined diegetic object, presenting the hero and the national flag as twinned objects of desire (Figure 3.13). The national flag in the background symbolises the presence and victory of the Party, without which the hero cannot triumphantly return and reunite with his implied lover, the heroine. In this reunion sequence, the camera set-up on the ocean creates an exchange of gazes typical of the shot/reverse-shot convention, but without any indication of physical touch, at the same time heightening audience identification with the hero, the heroine and the Party.

Figure 3.13 The relay of gazes in Sea Hawk (1959) points to an off-screen space with a defined diegetic object, presenting the hero and the national flag as the heroine’s (and the ideal audience’s) twinned objects of desire.

Unlike classical Hollywood narration, in which the dual plot of romance and work achieves closure with love consummated and mission accomplished, Chinese revolutionary cinema resolves the dual plot with mission accomplished through the sublimation of private desire. Recall Ban Wang’s claim about the ‘recycling of the individual’s libidinal energy for revolutionary purposes’; echoing it, McGrath supplements his sublimation thesis by looking at how genre conventions of classical Hollywood heteronormative romance – visual elements of the mise-en-scène, shot/reverse-shot editing, close-ups and non-verbal performance cues – are deployed to facilitate sublimation.60 Chinese revolutionary film typically lacks overt physical touch; compare the embraces in The Fall of Berlin with the reuniting couple in Sea Hawk, who stand on two boats separated by a stretch of the sea. In Chinese revolutionary film, romance and reunion are conveyed through shot/reverse-shot editing and camera set-ups, through visual rather than physical connexion, so that a revolutionary goal is accomplished through sublimation.

Figure 3.14 Neither relayed through other major or supporting characters nor punctuated by empty shots, Qionghua’s gaze becomes properly socialist as she leaps to political consciousness as a Party member in The Red Detachment of Women (1961).

In revolutionary films such as Song of Youth (Cui Wei and Chen Huaikai, 1959) and The Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin, 1961), however, the narrative trope of martyrdom – the death of a male hero – establishes the surviving female lead character as the custodian of the socialist realist gaze. In The Red Detachment of Women, a montage sequence signals the heroine’s epiphany and leap to political consciousness. At a critical moment in the film, Qionghua, having witnessed the death of her mentor and implied lover, Changqing, encounters the official papers approving her admission to the Party. The sequence cuts to an extreme close-up shot of Qionghua’s gaze, superimposed with Party documents (Figure 3.14). The montage sequence, combined with subjectified sound (the Internationale), visually and aurally evokes her psychological reactions through a highly condensed succession of visual motifs: Party documents and Qionghua’s socialist realist gaze.

The montage sequence can also be read as the moment when Qionghua’s libidinal energy is rechannelled and sublimated into political goals – the Party becomes Qionghua’s locus of memory after her mentor (and implied lover) sacrifices himself for a revolutionary cause. Hence, the attractions that the montage sequence creates are in part derived from the unconsummated romance between Qionghua and Changqing.61 Qionghua’s gaze becomes properly socialist because it is neither relayed through other major or supporting characters nor punctuated by empty shots. Instead, her gaze points to an off-screen space without a defined diegetic object, signalling her leap to political consciousness. The document certifying her admission to the Party defines her gaze as one that belongs exclusively to Party members.

Since spectators implicated in the visual logic of the relay of gazes are central to the evolution of the socialist realist gaze, I suggest that the use of montage in Chinese revolutionary cinema was premised on the theoretical notion that film viewing is a collective and a participatory experience on a sensual and ideological level. Cinematic attraction, after all, is premised on direct visual and aural stimuli and the reactions of the audience, as Eisenstein underscores in his explications of the montage of attractions:

The attraction (аттракцион) has nothing in common with the stunt (трюк) […] In so far as the trick (трик) is absolute and complete within itself (в себе) [original emphasis], it means the direct opposite of the attraction, which is based exclusively on something relative, the reactions of the audience (реакции зрителя).62

In the hands of Chinese film-makers, montage was reinvented to provoke, attract and persuade the audience at the level of the senses, but without the kind of intellectual leap required by the montage of attractions.

The formal categories described in this chapter – relay of gazes, comparative montage and the use of revolutionary songs and subjectified sound – help us to understand how Chinese film-makers adapted the montage as series and montage of attractions from Pudovkin and Eisenstein in creating affective moments in Chinese revolutionary films. Their adherence to Hollywood continuity editing and the maintenance of narrative economy and diegetic contiguity allowed Chinese film-makers to strive to make films accessible and comprehensible by a rural mass audience. Their reinvention of montage as an umbrella term for all film editing methods not only served to unveil montage and reduce its strangeness, but also allowed Chinese film-makers and critics to swiftly traverse both Hollywood continuity editing and Soviet montage in repositioning Chinese cinema vis-à-vis its foreign counterparts.

In her study of film export from the PRC in 1949–57, Tina Mai Chen calls for rethinking the early years of PRC cinema ‘not as a period of disengagement from world cinemas, but as part of linked political, social, economic and cultural projects within the PRC that brought the national to the international – and vice versa’.63 The riddle of montage and the evolving discourse around it since the 1930s shed light on the ways Chinese film-makers and cultural authorities actively pursued theoretical and practical dialogue with Soviet film theories and other cinematic precedents. Highly informed by international film theory, Chinese revolutionary cinema was not a passive recipient in the dissemination of film theory, but an active participant in rereading (or even creatively misreading), redefining and reinventing montage.