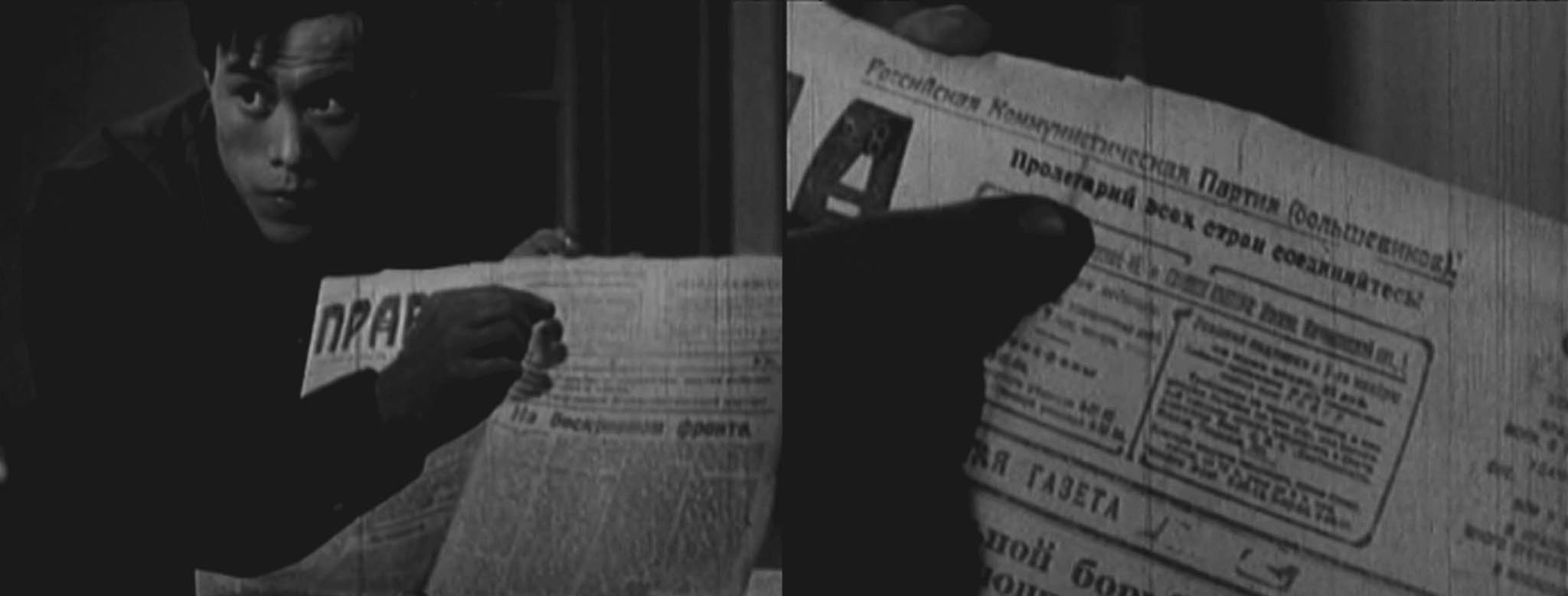

Figure 5.1 The Chinese film journal Film Art (Dianying yishu) (issue 1, 1961) highlighted this shot as a ‘touching’ (dongrende) moment of solidarity in the Sino–Soviet co-production Wind from the East (1959).

5

Visions of Internationalism in

Chinese Film Journals

Cinematic experiments in the realm of aesthetics were not isolated from Cold War politics. The propaganda state developed ambitious visions of internationalism and redefined this malleable concept in the shifting terrain of the Cold War. In the wake of decolonisation, the postwar period witnessed competing visions of socialist and liberal internationalisms. As an organised social movement and an institution, internationalism originated in nineteenth-century workers’ movements. The establishment of the Socialist International prior to World War I and the Comintern after the 1917 Russian Revolution were followed by the postwar emergence of intergovernmental and transnational institutions – the League of Nations, the United Nations, the International Labour Organization and the World Health Organization. These institutions represented the rise of Western liberal internationalism that aimed to counter socialist bloc internationalisms through developmental aid to the Third World. The ideological and political permutations of internationalism defined the tumultuous twentieth century through two World Wars, the Cold War and the disintegration of the socialist bloc. In the twenty-first century, the shifting language of internationalism remains central to political and aesthetic discourse: from ‘international’ relations to ‘transnational’ corporations, ‘cosmopolitan’ style to economic ‘globalisation’. The specific term ‘international’ has ‘retained currency across the century as the connective space that gave meaning to those other terms’.1

For the purposes of my argument, the term ‘internationalism’ must be clearly distinguished from ‘transnationalism’ and ‘cosmopolitanism’, although they often overlap in colloquial use. The latter terms denote the penetration of borders and the movement of capital, goods, technology, cultural artefacts and people between or beyond a given nation. ‘Transnationalism’ is a relatively recent term, coined in response to the term ‘globalisation’, while ‘cosmopolitanism’ can be traced back to the European eighteenth-century Enlightenment. ‘Internationalism’ acquired specific political connotations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with the emergence of European socialist parties, the world’s first communist regime, and the new world order of liberal democracy. In using the term ‘internationalism’, therefore, this chapter emphasises the contested and contingent nature of the term during the Cold War, the background against which the young PRC articulated its vision and identity within the socialist bloc and beyond. Internationalism was closely imbricated with nationalism, and both concepts helped construct and reinforce the identity of the PRC as a socialist nation-state.

This chapter is premised on two underlying notions: that internationalism, far from being a utopian ideal, had real implications in policy making in the realm of cultural diplomacy; and that the rhetoric of internationalist friendship and solidarity carried a high degree of emotional valence. Chinese film journals constructed an ideal domestic and international audience, one composed of socialist and non-socialist subjects with an explicitly international, anti-colonial and anti-imperialist subjectivity and worldview. Extensive coverage of film festivals, film theories, film technologies, and films from abroad performed an act of geopolitical and cultural mapping by creating an alternative space for internationalism to flourish among competing socialist bloc articulations, as the socialist bloc’s unity slowly disintegrated during the Cold War. Chinese film journals articulated visions of internationalism in two major international watershed moments. Initially, they positioned Chinese film production as learning from the Soviet ‘elder brother’, in accordance with the policy of ‘leaning to one side’ after 1949. In the post-Bandung era following the 1960s Sino–Soviet split, Chinese film journals envisioned Afro–Asian–Latin American solidarity. The investment in internationalism as part of state propaganda was the means by which the PRC strove for world recognition and, in the process, defined Chinese cinema as socialist and revolutionary.

Internationalism

Recent studies of socialist culture have shown that socialist propaganda states, far from being xenophobic, pursued cultural appropriation of various kinds in order to make their cultures great and recognised by the world. Katerina Clark calls the Soviet openness to Western European culture a kind of cosmopolitanism, observing that when the Soviet Union was perceived as at its most self-enclosed, it was actually at its most outward-looking: ‘Paradoxically, even as the Soviet Union became an increasingly closed society, it simultaneously became more involved with foreign trends.’2 On a similar trajectory, Nicolai Volland considers Chinese socialist literature of the 1950s an example of ‘socialist cosmopolitanism’, mapping the literary exchange and translation of foreign literature in what he calls the four concentric circles of the Chinese literary universe: the Soviet Union at the core, followed by socialist Eastern Europe and Asia and the Third World, with progressive literature from Western Europe and the United States on the periphery.3 Noting that Western European classics and works of the ‘beat generation’ continued to circulate through unofficial channels during the Cultural Revolution, Volland sees cosmopolitanism as being ‘clandestine’ in socialist China.4 Paula Iovene’s exploration of ‘literary internationalism’ shows that the Chinese literary journal Yiwen, founded in 1953 (Shijie wenxue from 1959 onwards), functioned as an ‘atlas of world literature’ by introducing literature from Asia, Africa, Latin America, Europe and North America.5

These studies explore the outward-looking nature of the socialist project in building a culture of its own, primarily in the literary realm. We are coming to understand that interactions within and beyond the socialist bloc during the Cold War must be understood as international, rather than domestic, history:

The socialist countries’ foreign policies, toward each other and toward the broader world, cannot be studied in isolation from one another. The makers of the socialist bloc talked about this constantly – if only to clarify their mutual commitment to each other and to the virtues of what they called ‘internationalism’, ‘unity’, the ‘socialist community’, or even what the East Germans liked to call the ‘socialist world economic system’.6

Socialist countries were outward-looking in appropriating other cultures. Moreover, their interconnectedness, often evoked in the rhetoric of friendship and solidarity, also meant that major events or crises within the bloc set off ramifications with domestic and international implications. The 1956 uprisings in Poland and Hungary, for instance, had critical implications for the Hundred Flowers Campaign and the Anti-Rightist Campaign. Khrushchev’s policy of peaceful coexistence and the ensuing Sino–Soviet rift reshaped Mao’s foreign policy towards the Third World. An international perspective in the study of socialist film culture – in this case, the discourse on internationalism itself – is indispensable.

The origins of competing socialist and liberal internationalisms can be traced back to the first half of the nineteenth century, when free trade and liberal capitalism were lauded as vehicles of peace and internationalism. Marx and Engels, in the last line of the 1848 Manifesto, called on the workers of the world to unite in world revolution and overthrow the capitalist world order. In 1864, the International Association of Workers (the First International) was formed, a major outcome of transnational demands for a nine-hour day put forward by workers led by the London Trades Council. Despite its dissolution in the 1870s due to internal tensions, the ‘International’ assumed ‘the value of a symbolic identity for the working classes’.7 The ‘Internationale’ song was written in 1871, and the ‘Second International’ was formed in 1889 as an organisation of various national socialist parties. It too dissolved, because of the differing stances of the socialist parties regarding the outbreak of World War I.

The Communist International (1919–43) (Comintern, also known as the Third International), which split off from socialist internationalism and grouped together various nascent communist parties, sought to overcome the weaknesses and contradictions of the previous Internationals. As Patrizia Dogliani puts it: ‘World War I and the Russian Revolution were at the root of the split between the two major internationals of the nineteenth century: socialist and communist.’8 Yet the 50 years from 1889 to 1939 were ‘the golden age of the socialist international’, a period in which parties and movements of socialist or Marxist inspiration grew and prospered.9 The first Comintern school, the Communist University of the Toilers of the East, was set up in Moscow in 1921, targeting mainly Asian students. The League of Nations, dominated by Western liberal democracies, was established in response to ‘the threat posed by the Bolshevik Revolution and the alternative international model that it promoted’.10 The competing strands of internationalism continued to manifest themselves in the postwar period, as competing political visions and internationalisms were projected onto the Third World.

The rhetoric of internationalism carried a high degree of emotional valence, whether reinforcing socialist or liberal values and beliefs. Postwar internationalism can be understood as a ‘competition of development models’ as the First and Second Worlds universalised their beliefs and values to other parts of the world:

On the Western side, words like ‘betterment’, ‘development’, ‘help’, and ‘rescue’ were regularly used, referring to the missionary, humanitarian and philanthropic dimensions at the heart of international intervention. On the Eastern side, ‘solidarity’ and ‘friendship’ were key words and pointed to the supposed equality between donors and receivers, as well as their common fight against the imperialist oppressor.11

In re-examining the history of internationalism, Glenda Sluga and Patricia Clavin have pointed out that the realism of the nation-state is often set against the idealism of the international community. One consequence of this realist–idealist divide is that internationalism is often presented as politically marginal to the project of the nation-state.12 Yet far from being a utopian ideal, internationalism had real implications in policy making in the realm of cultural diplomacy. Akira Iriye has defined ‘cultural internationalism’ as ‘the fostering of international cooperation through cultural activities across national boundaries’.13 I contend that Chinese film journals composed a cultural internationalism premised on cinematic exchange through film festivals, film theories, film technologies, and films from abroad. In these journals, the rhetoric of solidarity and friendship gradually shifted, in the 1950s and 1960s, from the Soviet Union to Asia, Africa and Latin America. This chapter discusses internationalism as a political project, a community and an identity. As a political project, it encompassed a vision of international order. As a community, it generated a network of cinematic exchanges. As an identity, it bound socialist and non-socialist subjects across national borders.14

In her study of film export patterns from the PRC to socialist and nonsocialist countries, Tina Mai Chen offers the term ‘socialist geographies’ to refer to the ways that film export and import, international film exhibitions and travelling film technologies articulated visions of modernisation and internationalism as national and global projects.15 By analysing export and import patterns, audience figures and filmic texts, and the relations between them, Chen delineates shifting temporal and spatial hierarchies within the socialist bloc. Her work highlights the malleability of the term ‘internationalism’ throughout the 1950s and 1960s, as the PRC increasingly appropriated the Soviet Union’s role as a visionary leader of socialism in relation to Asian, African and Latin American countries. During this period, film journals acted as a lens through which Chinese cinema looked out on and projected itself to the world.

Lean to One Side: From Dubbing to Sino–Soviet Co-Production

In the early years of the PRC, Chinese film journals focused on learning from the Soviet ‘elder brother’ in accordance with the policy of ‘leaning to one side’. Temporal and familial metaphors represented the ‘complex web of temporalizations through which Chinese, Soviet and international socialism acquired meaning’.16 Slogans glorifying brotherhood with the Soviet Union, such as ‘the Soviet Union’s today is our tomorrow’, abounded in Chinese film journals of the early 1950s.17 The Soviet Union, the birthplace of the October Revolution, was conceived as the leader and pioneer of socialism. The early PRC relied heavily on Soviet film expertise. From 1949 to 1957, China imported 1,309 films (including 662 feature films), of which almost two-thirds came from the Soviet Union.18 Tina Mai Chen identifies two forms of technology that figured prominently in Sino–Soviet film exchange: ‘technologies of translation’, which include dubbing and subtitling, and ‘technologies of distribution’, which include film projectors and other forms of film machinery.19 In 1949, the first Soviet film dubbed into Chinese was Leonid Lukov’s Alexander Matrosov (Yige putong de zhanshi/Putong yibing). In the next year, 1950, the national film plan envisaged the dubbing of 40 Soviet features to fill the ideological gap after the elimination of Hollywood movies from the Chinese market.20 By the end of 1953, more than 100 Soviet films had been dubbed and subtitled.21

In December 1953, a conference on dubbing and subtitling was held in Beijing for a week, marking the accomplishment of the work of dubbing since the establishment of the PRC. The conference received extensive coverage in the film journal The People’s Cinema (Dazhong dianying). The 30 or so participants included directors, translators and voice artists from the Northeast Film Studio and the Shanghai Film Studio. A slogan at the conference venue made clear the importance of film translation: ‘Dubbing and subtitling are important tools for promoting socialism.’22 Cai Chusheng spoke of the significant impact of dubbing and subtitling on the ‘political and cultural lives’ of the people and the nation, explaining that film art enabled people to learn from the ‘advanced cultures’ (the Soviet Union) of the world.23 In 1954, the national film plan announced the dubbing and subtitling of more than 40 films (mostly Soviet films), such as the Soviet biopic Belinsky (Grigori Kozintsev, 1953).24 By 1957, 206 Soviet feature films, 59 full-length documentaries and science and education films, and 202 various short films – including 24 animation films, 39 short documentaries, and 139 short science and education films and other newsreels – had been dubbed and subtitled in Chinese.25

Dubbing was perceived as superior to subtitling due to both the technologies of dubbing and the creative labour involved. As Tina Mai Chen contends, dubbing was conceived as ‘the most advanced and efficient of available translation technologies’ and the use of state studios to dub imported Soviet films ‘marked a shift in China’s status as modern’.26 This shift, and its revolutionary significance, were marked by Chinese film journals. The People’s Cinema published an article titled ‘Hard and Creative Labour’ in 1954, introducing to readers the behind-the-scenes work required for dubbing. Dubbing, the article explained, required two major steps: the translation of a screen script and ensuring lip synchronisation (dui kouxing). Translators were required to maintain the length of the original dialogues, and the translated script in Chinese had to match the foreign tongue and its lip movements. Otherwise, one would encounter ‘the weird situation where the mouth is shut on screen but the voice is still going, or the lips are moving but no voice is coming out’.27 For a close-up, the article went on, ‘one has to lip-sync word by word’.28 Lip synchronisation required voice actors to synchronise with the voice and emotions of the characters, while maintaining uniformity in pace of speech and lip movements, to create the impression that ‘foreigners on screen can speak Chinese naturally [my emphasis]’.29 Voice actors were expected to prepare themselves for their roles by reading books about their characters or interviewing people in real life. Dubbing was said to require more artistic cultivation on the part of voice artists. Moreover, the need to render the work of translation invisible on screen through seamless synchronisation meant that dubbing required a higher degree of technological sophistication than subtitling. Dubbing was conceived as having the potential to overcome language barriers and to render the foreign immediately translatable and intelligible – like magic. Dubbing therefore naturalised the fashioned affinity with the Soviet ‘elder brother’ on screen.

The first Sino–Soviet co-production, Wind from the East (Feng cong dongfang lai) (В едином строю) (Efim Dzigan and Gan Xuewei, 1959), constructs an ideal domestic and international audience with an international subjectivity.30 The feature film, dubbed entirely in Chinese, was co-produced by the Changchun Film Studio and Mosfilm. It was shot in 1957 and released in 1959 to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the PRC.31 Wind from the East tells the story of how Chinese and Soviet engineers and workers heroically combat a flood that endangers a hydropower station in China (Figure 5.1). The narrative interweaves Sino–Soviet collaboration with the lead characters’ reminiscences of their friendship. Rescued by Matveyev during the Russian Civil War, Wang Demin aspires to learn from his Soviet brother in arms. In a sequence portraying Saturday voluntary labour in Moscow, Wang voices his internationalist aspirations to his fellow multinational volunteers from the Comintern: ‘How I long to see Lenin, so that I could tell my fellow countrymen what Lenin is like!’ The sequence ends in a moment of solidarity, with Comintern representatives from various countries joining hands as they say where they come from: ‘China, Czechoslovakia, France, Bulgaria, Germany, Britain, the United States, Romania, Finland, Greece, Poland, Soviet Russia’ (Figure 5.2). Imprinted in the characters’ subjectivity, and by extension that of the ideal audience, international aspirations and the language of friendship with the Soviet Union drive the narrative forward.

Figure 5.1 The Chinese film journal Film Art (Dianying yishu) (issue 1, 1961) highlighted this shot as a ‘touching’ (dongrende) moment of solidarity in the Sino–Soviet co-production Wind from the East (1959).

Figure 5.2 Multinational representatives from the Comintern joining hands in Moscow.

In a later sequence shot in a picturesque snow-filled Red Square, Wang and Matveyev, serving as guards, are greeted by Lenin, who is drawn to Wang and greets him with ‘nihao’. Lenin’s warm greeting in Chinese is also a pedagogical moment for Matveyev: ‘You [Matveyev] are still young and should learn Chinese. It will be useful in the future. It will be extremely useful.’ The sequence continues in Lenin’s office, where Wang and Matveyev are invited for a chat. Speaking as both pedagogue and father of the Russian Revolution, Lenin asks them to translate a few words from Russian into Chinese and vice versa. Lenin’s translation tasks are a test and a lesson, which Wang completes admirably by reciting Pushkin’s poetry, translating revolutionary slogans and communicating effectively in Russian.

Wang demonstrates his communist discipleship and internationalist aspirations by eagerly telling Lenin that his friend Matveyev is teaching him Russian. Wang eloquently recites a few lines of Pushkin’s poetry, the first moment in the film when we hear him speak Russian. Wang humbly remarks on the beauty of Pushkin’s poetry, expressing regrets that he ‘cannot even speak [Russian] properly’. Impressed by Wang’s poetic sensibility, Lenin turns to Matveyev and asks him to translate the slogan ‘proletariat of all countries, unite!’ (quan shijie wuchan jieji tuanjie qilai) from Chinese into Russian. Holding a magnifying glass, Matveyev utters each Chinese character slowly and struggles to translate the slogan into his mother tongue. Wang, standing behind Lenin, helps Matveyev by quietly pointing to the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Pravda (Truth), where the slogan is printed as a small headline in Russian (пролетарии всех стран соединяйтесь) – demonstrating that he can read and translate Soviet revolutionary slogans as well as reciting poetry in Russian (Figure 5.3). Once Matveyev gets it right by cheating, Lenin laughs: ‘I caught you! Dear, I caught you! Remember, if you want to teach others, you must be a good student first.’ Wang outperforms his teacher and friend Matveyev, demonstrating how well he has learned from his symbolic ‘elder brother’ and implicitly suggesting that the younger brother has equalled, if not bested, the elder’s internationalist credentials.

Figure 5.3 Wang Demin demonstrates that he can read and translate Soviet revolutionary slogans, outsmarting his teacher and brother in arms Matveyev, who struggles with Chinese.

At the end of the sequence, Matveyev conveys to Lenin his desire to help build power stations in Vladimir. Wang joins in, adding a call in Chinese for ‘electrification of the entire Soviet Union’ (quan’e dianqihua), followed by the Soviet slogan ‘Коммунизм – это Советская власть плюс электрификация’ (Communism is Soviet power plus electrification), spoken in Russian.32 This is the second time in the sequence when we hear Wang speaks Russian, demonstrating that he can switch from Chinese to Russian quite comfortably and paying homage to both Russian literary classics and Marxism-Leninism.

Commenting on Chinese acting in 1959, the lead Soviet actress of Wind from the East, Viktoriya Radunskaya, posited an ideological, aesthetic and even physical affinity that transcended language: ‘Chinese and Soviet actors share the same language. Our friends – young Chinese actors – are very familiar with Stanislavski’s system. We were both educated under realism. Therefore, the language barrier does not affect our mutual understanding.’33 Screen acting and dubbing allowed an actor’s corporeal body to be seen and heard speaking in the audience’s language. In creating a shared cinematic language, Chinese and Soviet actors sought to overcome linguistic differences and articulate a shared international subjectivity.

Celebrating Soviet Film Weeks and the October Revolution in Chinese Film Journals

To celebrate the anniversary of the October Revolution, annual Soviet film weeks were held in the PRC in the month of November from 1952 to 1956. These Soviet film weeks featured visits from Soviet film delegations and exhibitions of Soviet films that functioned as educational models. These film weeks ‘constituted a series of experiments wherein the Chinese state, film industry and audiences engaged multiple film circuits at a local scale’.34 In some years, Soviet film weeks in China were paired with visits by Chinese film-makers to the Soviet Union. For instance, in 1954, a Soviet film week was held in 30 Chinese cities; in the same year, the PRC sent a film delegation to the Soviet Union that included Zhang Junxiang, Yuan Wenshu and the actresses Qin Yi and Zhang Ruifang. In a special article on that year’s Soviet film week, titled ‘A Glorious Model’, a writer extols: ‘The Soviet Union’s today is our tomorrow. We are marching forward on the same path that the Soviet people have travelled.’35 Three years later in 1957, The New Year’s Sacrifice (Sang Hu, 1956) was screened in the Soviet Union, accompanied by a film delegation that included Bai Yang, Huang Zuolin and Sang Hu. A 1957 issue of Shangying Pictorial (Shangying huabao) included extensive coverage of Soviet cinema to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution. In one article, a historical overview of Soviet film in China, the writer presented Soviet cinema as a benefactor that provided ‘spiritual nutrients’ (jingshen yingyang) for Chinese art.36 Elsewhere in the same issue, terms such as ‘intimate friendship’ (qinmi youyi) and ‘evergreen friendship’ (youyi changchun) were used to describe China’s partnership with the Soviet Union.37 These metaphors of friendship and intimacy in Chinese film journals represented internationalism and socialist solidarity as a personal relationship, while recalling the Soviet turn in Chinese film discourse in the Republican era.

As in the Republican era, Soviet cinema was seen as a model for Chinese cinema. The 1957 November–December combined issues of Chinese Cinema (Zhongguo dianying), celebrating the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution, published a letter to the Soviet film journal Film Art (Искусство кино). The letter was written by the editorial boards of Chinese Cinema and Film Art Translations (Dianying yishu yicong). In the letter, the editors of the two Chinese film journals described Soviet cinema as ‘a pioneer of film art’ that ‘defined a new direction for film art in the world’.38 In a metaphor that anticipated Wang Demin’s portrayal as a student of the Russian language in Wind from the East, another critic wrote that every Soviet film was a ‘lively visual textbook’.39 In the same issue, Chen Bo wrote: ‘The sun of the October Revolution rises from the East and shines brightly. We, under the shining and glorious sun, follow the path of the October Revolution.’40 This rhetoric of the ‘East’ (as opposed to the ‘West’), like the Chinese title of the Sino–Soviet co-production Wind from the East, articulated a Soviet-pioneered and Soviet-led vision of internationalism.41

The production and consumption of Chinese film journals fostered and satisfied a thirst for learning and engagement with foreign cinema. Far from being xenophobic, Chinese film journals published during the Seventeen Years from 1949 to 1966 consistently tried to internationalise their coverage while advertising Chinese cinema to the world. Filled with colourful illustrations, advertisements, film commentaries and pictures of socialist stars foreign and domestic, Chinese film journals informed readers of behind-the-scene happenings, film terms, technological practices and film production goals. Chinese film journals oriented readers to look outward, keeping them up-to-date about film happenings all over the world – not only within the socialist bloc but also beyond. After the Sino–Soviet split in the 1960s, the PRC took on the role of a leader in the socialist bloc and beyond, presenting a new vision of internationalism. When the ‘wind from the east’ shifted, China stepped into the role of its elder brother.

Film Art Translations

What follows is a brief overview of a few noteworthy Chinese film journals. The monthly Film Art Translations (Dianying yishu yicong, founded in 1952, discontinued in 1958, and restarted in 1981 as Shijie dianying) played a pivotal role in translating Soviet film theories and criticism into Chinese. Its coverage focused mostly on the Soviet Union, with occasional discussion of French and Japanese film criticism. From 1952 to 1956, the journal translated over 50 Soviet film scripts and over 50 Soviet theoretical works about film, including the major works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Stanislavski. Issues from 1955 to 1958 featured a column called ‘Learning Stanislavski’s Acting System’. The 1958 inaugural issue of International Cinema (Guoji dianying), which succeeded the discontinued Film Art Translations, featured a collection of special essays on Eisenstein and Pudovkin to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Eisenstein’s death and the fifth anniversary of Pudovkin’s.

International Cinema

While Film Art Translations focused on translation, International Cinema represented a major shift in content and organisation as Sino–Soviet tensions emerged in the late 1950s. The inaugural issue described its predecessor as a journal that specialised in Soviet film theory and practice but ‘lacked research on Chinese film art’.42 The editor wrote that Film Art Translations ‘uncritically introduced theories that were obviously flawed, resulting in negative effects on readers’.43 To overcome the weaknesses of its predecessor, International Cinema, as its title suggests, was to strive for wider international coverage rather than focusing exclusively on Soviet film theory and criticism. Although coverage of Soviet cinema was reduced in International Cinema, Soviet revolutionary classics such as Lenin in October (Mikhail Romm and Dmitriy Vasilev, 1937) and Lenin in 1918 (Mikhail Romm, E. Aron and Isidor Simkov, 1939) still occupied a canonical position.44

Chinese Cinema

Iovene has suggested that the Chinese literary journal Yiwen, founded in 1953, (Shijie wenxue from 1959 onwards), functioned as an ‘atlas of world literature’ in its ‘literary internationalism’.45 She notes that beginning in 1957, the Soviet Union was replaced in the journal’s purview by a more inclusive formulation that emphasised the journal’s reorientation toward ‘all the countries of the world’.46 A similar reorientation occurred in other Chinese film journals at about the same time, as Sino–Soviet tensions surfaced. While Film Art Translations had treated mostly Soviet film theories and criticism in specialised language targeted to a sophisticated group of readers, the journal Chinese Cinema (Zhongguo dianying), founded in 1956, discussed a diverse range of foreign film magazines and film happenings in a user-friendly manner. Yomi Braester suggests that the founders of Chinese Cinema ‘sought to introduce a major change in the popular perception of film in China’ by drawing from Georges Sadoul’s notion of cinephilia during the brief thaw of the Hundred Flowers Campaign.47 Placing Chinese film in the context of world cinema, contributors to Chinese Cinema constructed ‘a community bridging industry insiders, professional critics and informed audiences’.48 Along with introducing domestic films, almost every issue of Chinese Cinema featured a one-page column introducing a foreign film journal to Chinese readers. The December 1956 issue introduced the Polish film journal Kwartalnik Filmowy, started in 1951. 1957 issues introduced Sight and Sound (UK, 1932), Cinema (France, 1955), Deutsche Filmkunst (Germany, 1953), Filmfare (India, 1952), the Italian journals Cinema Nuovo (1952) and Unitalia Film (published in English, French, German, Italian and Spanish), Czechoslovak Film (published in English, French, German, Russian and Spanish) and the Soviet film journal Sovetskii Ekran (1957). In 1958, Chinese Cinema profiled Korean Film (Korea, 1957) and the Vietnamese journal Film (1957).

As the list indicates, Chinese Cinema introduced a diverse range of the most current foreign film journals from all over the world.49 One column writer, commenting on the Vietnamese journal Film, highlighted the similar missions of Film and Chinese Cinema. The column writer complimented the way the Vietnamese film journal introduced The New Year’s Sacrifice, translated its film script, and by extension introduced films from ‘brotherly nations’ such as China.50 A column on Sight and Sound disapproved of the way the journal ‘separated art from economics’.51 Nonetheless, the column writer allowed that ‘[a]lthough it tends towards an aestheticism that transcends class, it has its own practical usefulness.’52 The most useful features of Sight and Sound were said to be essays that introduced film artists and theories from the West, categorised into four groups: ‘The problem of film art, research on film history, essays on film artists, and film criticism.’53 As Volland suggests, foreign literature and literary developments ‘remained a crucial benchmark, indicating the larger framework within which Chinese [socialist] literature imagined itself.’54 Foreign film and cinematic developments in the capitalist bloc remained relevant and even crucial in shaping the worldview and self-understanding of Chinese socialist cinema.

Redefining Red Friendship: Post-Bandung Afro–Asian–Latin American Solidarity

We hear the groans of the people.

Their eyes shine with the spark of anti-imperialist struggle.

March on, our brothers in South America and Africa!

We are gazing at your struggle for justice.55

– ‘March On, our Brothers in Latin America and Africa!’ Sun Daolin, Zhang Ruifang, and Qin Yi

In the late 1950s following de-Stalinisation, the post-Bandung era envisioned Afro–Asian–Latin American solidarity. Red friendship was redefined, turning the spotlight away from the Soviet Union to Asian, African and Latin American countries. This shift in cinematic alignment was a result of Cold War politics. After Khrushchev’s secret speech in the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956, which initiated de-Stalinisation and the ‘thaw’, the Soviet Union was no longer seen as free from ideological flaws and revisionism. As Anne E. Gorsuch and Diane P. Koenker suggest in their critical examination of the ‘socialist sixties’, Khrushchev’s doctrine of peaceful coexistence enabled ‘unprecedented international contact’, in which ‘encounters with the West’ became the thaw’s defining experience.56 The 1960s saw the rise of Soviet consumerism, as ‘previously condemned aspects of “Western” culture – fashionable clothing, urban cafes, light jazz – were domesticated and made acceptably socialist.’57 The ‘Kitchen Debate’ between Richard Nixon and Khrushchev at the 1959 American Exhibition in Moscow about the relative merits of their economic systems introduced consumption as ‘a site of Cold War competition over the “good life”’.58 Khrushchev’s policy reshaped the socialist bloc’s collective character, threatening its unity and revealing intrabloc competitions and tensions as the PRC became increasingly critical of Soviet ‘great power chauvinism’ and past Russian imperialism. Those tensions spilled over into the Third World as the First and Second Worlds universalised their beliefs, values and competing strands of internationalism in the form of developmental aid and anti-colonial rhetoric.

In fashioning a new internationalism as a counterforce against the Soviet–US peaceful coexistence, the PRC invested in anti-colonial and anti-imperialist rhetoric. Key to understanding the PRC’s new vision of internationalism is the notion of ‘solidarity’ in creating an anti-colonial imaginary that boosted socialist China’s image at home and abroad. In his study of East German discourse on Africa and SWAPO (South West Africa People’s Organisation), Toni Weis suggests that ‘solidarity’, often used in deliberate opposition to the Western concept of development, ‘was meant to describe a relationship among equals, based on the idea of reciprocity and the membership in a shared moral community’.59 In creating an anti-colonial imaginary in solidarity with the Third World, the PRC emphasised their ‘common encounter with European colonialism and difficult exposure to Soviet aid, advisers, and forms of socialist bloc collaboration’.60

Film advertisements and the representation of film festivals and cinematic exchange in Chinese film journals played an important role in constructing this alternative vision of internationalism, one that was much broader in scope than the previous brotherhood with the Soviet Union. Chinese film journals fashioned an alternative mode of temporality and remapped world cinematic space, shifting its centre of gravity from the ‘West’ to the ‘East’ and eventually to Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Asian Film Weeks and Afro–Asian Film Festivals

Film weeks and film festivals were no less important than film production. Often receiving extensive coverage in film journals, film weeks and festivals were important venues for advertising and circulating foreign films in China, and Chinese films abroad. Chinese film delegations often attended foreign film weeks and festivals, where prizes and honours were presented, and which served as opportunities to ‘exhibit the nation to the international community’.61

In the spirit of the 1955 Bandung Conference that served as a foundation for the Nonaligned Movement, the 1957 Asian Film Week (Yazhou dianyingzhou) ‘exemplified the PRC’s early experiments in choreographing an international event participated by multiple nations’.62 With a line-up of 17 films from more than ten Asian countries, the event was held in August in ten Chinese cities: Beijing, Changchun, Guangzhou, Hangzhou, Kunming, Nanjing, Shanghai, Shenyang, Tianjin and Wuhan.63 Participating countries included Burma, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Lebanon, Mongolia, Pakistan, the PRC, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. The closing ceremony announced that the event would be continued as the Afro–Asian Film Festival (Yafei dianyingjie), with each participating country rotating the organisational duties of the mobile event.

The first Afro–Asian Film Festival accordingly took place in Tashkent, Uzbekistan in 1958, followed in 1960 by a second festival held in Cairo.64 One of the main activities of both festivals was to preview films from various participating countries. The ‘social imaginary’ represented in Chinese film journals, as Tina Mai Chen calls it, was explicitly anti-colonial and anti-imperialist.65 For example, an article in International Cinema featuring the Afro–Asian Film Festival described film festivals as an opportunity for participating countries to learn from the editing, performance, music and photography of exhibited films, and praised the way ‘[p]eople in Asia and Africa are marching ahead in the struggle against colonialism and imperialism’.66

The Third (and last) Afro–Asian Film Festival, held in Jakarta in April 1964, was an unusual festival that spurred anti-American sentiments. Participating countries included Afghanistan, Cuba, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Japan, Korea, Lebanon, Mali, Mongolia, Pakistan, the Philippines, the PRC, Somalia, the Soviet Union, Tunisia, Uganda, Vietnam, Zambia and Zanzibar. A few countries including Mali, the Philippines, Tunisia and Zanzibar presented films at an international festival for the first time. The Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin, 1961) received the Bandung award at the festival. After the festival, on 9 May, 16 organisations in Jakarta initiated a campaign for a boycott of US films throughout Indonesia.

The Chinese film journal Film Art responded to the boycott eagerly with an article titled ‘Resolutely in Support of the Indonesian Struggle against American Film’. The article described Hollywood movies as tools of ‘cultural invasion’ and ‘ideological infiltration’ because Hollywood movies dominated as much as 60 per cent of the market share in Indonesia. In contrast, only 15 domestic films were produced annually in Indonesia.67 An article in China’s Screen, titled ‘Revolution in the Afro–Asian Film World’, described the nationwide screening of Afro–Asian films and the boycott of American films in Indonesia as an ‘unprecedented revolutionary act’, and the Afro–Asian film festival in Jakarta as a ‘revolutionary’, ‘progressive’, and ‘healthy’ ‘festival of unity’.68 The Afro–Asian Film Festival was therefore not only a venue for cinematic showcase and exchange; it was also a highly political event that stirred revolutionary sentiments and called for collective action.

In addition to the Asian Film Week and the Afro–Asian Film Festival, the PRC held film weeks featuring films from specific countries in Asia and Latin America. A Mexican film week was held in 1959 in Beijing, Shanghai and Wuhan, where Espaldas Mojadas (Wetback/Toudu de kugong) (Alejandro Galindo, 1955) was shown. The Burmese Film Week was held in 1960, the ‘Year of Sino–Burmese Friendship’, during which Film Art described the friendship and cultural exchange between China and Burma as ‘family-like’ and ‘the most ancient’.69 Though ‘severed by imperialism’ in the late nineteenth century, the Sino–Burmese relationship was ‘restored after liberation and independence’.70 In September 1964, a Vietnamese Film Week was held in Beijing, Guangdong, Shanghai and three other Chinese cities to celebrate the nineteenth anniversary of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam).71 China’s Screen described China and Vietnam as ‘neighbours’ and ‘brothers’, whose relationship was as close as ‘lips and teeth’.72 The familial and temporal metaphors that had been used to fashion brotherhood with the Soviet Union were redirected to neighbouring nations with a similar colonial past, such as Burma, as the PRC reimagined itself as the leader of the Afro–Asian Third World. Socialist brotherhood was no longer exclusively tied to the Soviet ‘elder brother’; it was now extended to Burma and Vietnam in the name of anti-colonial solidarity.

Sino–Albanian Co-Production

Along with the Afro–Asian Third World, the PRC’s new internationalism extended to Albania, the only Eastern European socialist country that sided openly with China (particularly during the Cultural Revolution). Once a Yugoslav satellite, Albania relied on Soviet assistance after 1948, but abandoned that partnership for the PRC after the Sino–Soviet split in the 1960s. The worsening of Albanian–Soviet relations was due to Khrushchev’s rapprochement with Yugoslavia. Mao’s anti-Yugoslav and anti-revisionist rhetoric was very well received in Albania. When Moscow withdrew Soviet advisers and specialists from Tirana in 1961, Beijing agreed to step in and supply grain, factories and technology.73 Like the PRC, Albanian cultural authorities in the 1960s ‘sought to define a non-Moscow-centered way of being socialist in the world’.74 The first Sino–Albanian co-production, Forward, Side by Side (Krah për krah) (Endri Keko, 1964), was a full-length documentary featuring the ‘militant friendship’ between China and Albania around the ‘common cause of building socialism’ and ‘fighting imperialism and modern revisionism’.75 The film’s ‘Song of Red Friendship’ sang of ‘great oceans and high mountains set us far apart, but our two strong hands are tightly clasped together’, evoking the brothers-in-arms imagery previously used in the Sino–Soviet co-production Wind from the East. This time, however, China took on the role of an elder brother to Albania in the name of socialist and anti-imperialist solidarity.76

Forward, Side by Side and the Albanian feature film Extraordinary Mission (Teshu renwu/Detyrë e posaçme) (Kristaq Dhramo, 1963) were screened in Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan and other cities to celebrate the anniversary of the Albanian liberation. Albanian films and symbolic objects, such as the çifteli (a type of guitar) and Albanian cigarettes, continued to circulate in the PRC during the Cultural Revolution. The highly publicised and symbolic Sino–Albanian friendship demonstrated that even a small country such as Albania, as the ‘socialist light of Europe’, could play a role in big power politics.77

Advertising Chinese Cinema: The Multi-Language Film Journal China’s Screen

With the aim of internationalising its audience, the multi-language quarterly film journal China’s Screen, like foreign film journals such as Unitalia Film (published in English, French, German, Italian and Spanish) and Czechoslovak Film (published in English, French, German, Russian and Spanish), represented a major undertaking in advertising Chinese cinema to the world. With a local and international readership in mind, China’s Screen was published in Chinese, English, French and Spanish, and began to circulate in the 1960s.78 Eschewing coverage of Soviet cinema, China’s Screen focused almost exclusively on domestic film and films from Asia, Africa and Latin America. The multi-language journal, with its eye-catching mottos and colourful illustrations, represented the new anti-colonial internationalism, as the propaganda state acquired self-sufficiency and confidence in propagating and advertising the new identity of Chinese cinema as a socialist, anti-colonial and revolutionary cinema.

Both socialist and non-socialist countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America were on the radar of China’s Screen’s new internationalism. A 1964 issue featured an article titled ‘Progressive Latin American Films Popular in China’, in which films from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Cuba, Mexico and Venezuela were introduced to the journal’s local and international audience.79 ‘Reflecting the life and struggle of the Latin American people’, those films were well understood by the Chinese, ‘who shared a similar fate in the past’.80 The works of film-makers and authors with leftist leanings or activists in international front organisations were deemed ‘progressive’.81 China’s Screen’s use of the term extended its anti-colonial, anti-imperial and revolutionary sentiments to socialist and non-socialist subjects alike, in an aim to broaden its appeal to an international audience beyond the socialist bloc.

Several issues of China’s Screen in 1965 featured documentaries shot in Africa. An article introduced the Chinese documentary film The People of the Congo Will Certainly Win, which demonstrated the way Chinese people ‘support[ed] the Leopoldville Congolese people’s struggle’ and ‘condemn[ed] the crime of aggression committed against the Congo by US–Belgian imperialism’.82 Another article, ‘Forward, Africa! Fight On’, featured a provocative illustration that filled two pages, with a slogan from the full-length documentary Africa Marches Forward: ‘An awakened and mighty Africa is going to take her rightful place in the world.’83 The rhetoric here echoes Kasongo Kapanga’s suggestion that the national identity of Congolese literature and film is characterised by the ‘awakening to consciousness’ – the rise of consciousness of a collective plight – and the foundational urge to articulate that consciousness.84 China’s Screen, by articulating and propagating an awakened collective consciousness in its anti-colonial rhetoric, fostered a sense of belonging to an imagined yet concrete international community.

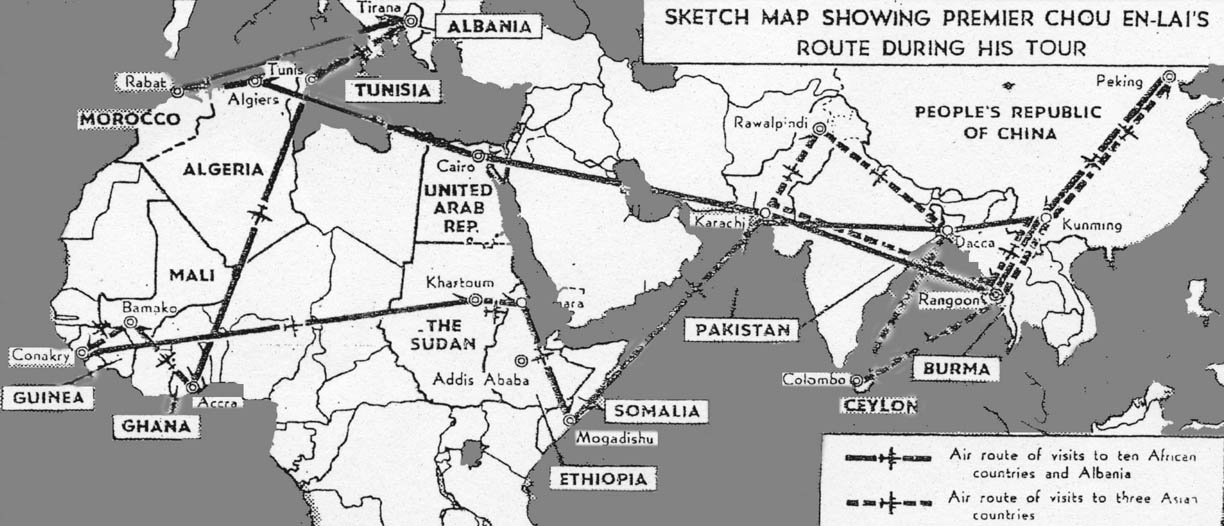

Like its literary counterpart Yiwen (Shijie wenxue from 1959 onwards), China’s Screen functioned as a cinematic atlas that boosted China’s self-image as a cinematic pioneer whose encyclopaedic quests and footprints reached the far corners of the world. Premier Zhou Enlai’s visits to Albania, Burma, Ceylon, Pakistan and ten African countries were featured in an article titled ‘A Militant, Many Splendored Friendship’. The article described Zhou Enlai’s journeys in ‘awakened, militant, and advancing Africa’: Algeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Morocco, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia and the United Arab Republic (Egypt) from December 1963 to March 1964.85 Employing expansionist logic, the article graphically mapped out Zhou Enlai’s tour, which ‘spanned a distance of 108,000 li in three continents’ (Figure 5.4).86 The tour ‘forged a bond of unity among comrades and friends’ and ‘drew a glittering arc of militant friendship between the revolutionary peoples’.87 The ‘glittering arc’ of friendship was lit by the PRC, as the sun of revolution whose rays reached three continents, awakening the people of Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe from their colonial plight. The revolutionary sun no longer resided in the Soviet Union. It rose from the PRC, the leader of the ‘East’, and shone over the far corners of the world, symbolically recasting notions of enlightenment and progress in socialist terms.

Figure 5.4 An illustrated map of Premier Zhou Enlai’s visits to Albania, Burma, Ceylon, Pakistan and ten countries in Africa, constructing a ‘glittering arc’ of friendship.

Zhou Enlai’s tri-continental tour was recorded in four documentaries produced by the Central Newsreel and Documentary Film Studio: Premier Zhou Enlai Visits Albania, Premier Zhou Visits Northern Africa, Premier Zhou Visits Western Africa and Premier Zhou Visits Northeast Africa. These were promoted in the aforementioned article, along with the tour map and Zhou Enlai’s words: ‘Our revolutionary sentiments burn together’.88 The article, tour map and documentary films made up a network of representation, revealing the anti-colonial imaginary and bonding the PRC with the revolutionary and potentially socialist community.

Emphasising the ‘age-old friendship’ between China and other Asian and African countries, the article echoed earlier efforts to glorify China’s ‘most ancient’ friendship with Burma.89 The ‘age-old friendship’ between China and many African countries, though severed by imperialism, was ‘restored’ after liberation: ‘Since China and many African countries regained their independence, all kinds of obstacles have been brushed aside and our age-old friendship has begun to shine with new luster.’90 The same was true of Burma, Ceylon and Pakistan, which all had ‘long-standing ties of friendship’ with China: ‘Our common lot as victims of imperialist aggression and oppression and our common task of fighting imperialism unite us and have added kinship to our age-old friendship.’91 A shared colonial past was constructed, situating the PRC and its brotherly nations along the same line of revolutionary struggle and liberation. This new vision of internationalism, premised on an anti-colonial and anti-imperialist solidarity, carried the PRC’s aspiration of expanding international influence as well as confidence in the superiority of Chinese socialism.

To further fashion the PRC as a leader whose light of revolution and socialist modernity reached the far corners of the world, China’s Screen publicised documentaries shot in African countries. The documentary film Visit to Uganda was promoted in China’s Screen in 1965 to show that since independence, the people of Uganda ‘have overcome all manner of difficulties in their efforts to build their country’.92 An article on ‘Chinese Cameramen in Africa’ introduced other documentaries shot in Africa: The Horn of Africa, Independent Mali, An Ode to the Nile, The People of the Congo Will Certainly Win and Resolute Algeria.93 Tina Mai Chen suggests that this production of ‘knowledge-based’ films ‘points to an increased independence and self-confidence within the PRC by 1956’.94 Documentaries filmed in African countries with an ethnographic gaze provided knowledge about brotherly nations while demonstrating the international reach of China’s film technology, establishing China as ‘an alternative center of knowledge’.95

Echoing earlier film journals like Shangying Pictorial (Shangying huabao), which had proclaimed that ‘Chinese film reaches the world’, China’s Screen, with an international readership in mind, proudly presented the Chinese film industry as self-sufficient and technologically advanced.96 ‘Some Facts about New China’s Film Industry’, written by Chen Huangmei in 1964, emphasised that China was ‘self-sufficient with regard to film apparatus and equipment, while exporting some products’.97 Cinematic exchange, Chen Huangmei went on, improved ‘mutual understanding between peoples of the world’ and forged ‘solidarity and friendship among the peoples’.98 Self-sufficiency, which laid the ground for film export, was conceived as a major accomplishment: the PRC no longer relied on Soviet assistance and imports as it took on a leadership role, exporting film and forging a new solidarity with countries that had revolutionary and socialist potential.

In addition to introducing Asian, African and Latin American films, China’s Screen advertised Chinese film to the world – which explains why the journal was published in Chinese, English, French and Spanish. The song and dance pageant The East is Red (Dongfanghong) was given extensive coverage. The East is Red proclaims the glory of revolution (and of Mao) in song and dance, telling the history of the Chinese revolution and its ensuing socialist construction. In ‘The East is Red: A Song and Dance Pageant’, China’s Screen described the performance as ‘revolutionary’, ‘national’ and ‘popular’.99 The journal’s extensive coverage of The East is Red, which was recorded on film in 1965, indicates the celebratory culmination of China’s self-image. In the period between the Sino–Soviet co-production Wind from the East and The East is Red, the PRC had displaced the Soviet Union as the leader of the ‘East’, whose revolutionary and socialist light emanated to the non-West: Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe and Latin America.

China’s Screen also featured international reactions to highly acclaimed Chinese films. Highlighting the success of domestic films in the eyes of others was a way to propagate and project China’s self-image to the world. An article on ‘The White-Haired Girl Abroad’ celebrated the success of The White-Haired Girl (Wang Bin and Shui Hua, 1950), which was subtitled in English, French and Spanish and screened in more than 30 countries. The article cited the praise of the Algerian newspaper, Le Peuple, for ‘the skillful way in which the director and actors synthesized the beautiful singing and the story’.100 Quoting Le Peuple, China’s Screen wrote: ‘This wonderful film was made under the enlightening guidance of the theories on art and literature propounded by Mao Tse-tung in May 1942.’101 It was also reported that a representative of the Malian motion picture department, after seeing the film, said: ‘Without dubbing, without subtitles, the acting alone is enough to move an audience to tears.’102 Music and the corporeality of acting were said to have overcome language barriers to reinforce mutual understanding between the Chinese and the Algerian audience. The inclusion of illustrations from Algerian and Vietnamese newspapers and magazines gave the article a sense of ‘truth’, albeit filtered by the state, in reporting the foreign success of The White-Haired Girl.

Another article, ‘A Most Outstanding Film: Reactions of Viewers Abroad to Five Golden Flowers’, described Five Golden Flowers (Wang Jiayi, 1959), a romantic comedy in an exotic ethnic setting, as a ‘refreshing change’.103 The article reported that the foreign audience ‘remarked on the pure [and] serious love shown in the film, so different from the love interest and perverse[ly] decadent emphasis on sex found in many Western films’.104 The contrast with ‘Western’ romance was emphasised to underscore the radical difference and ‘refreshing change’ that Five Golden Flowers provided; little was said about the ways the film appropriated classical Hollywood narration or its dual plot of romance and work. Five Golden Flowers was fashioned by China’s Screen as an alternative entertainment (pure love without a decadent emphasis on sex) and an ideological form (ethnic harmony under the guidance of the Han elder brother). Its foreign popularity demonstrated that Chinese socialist films were more attractive than ‘Western films’. ‘Some foreign friends’, the article continued, compared the film music to paradise: ‘The music is surely from heaven. How rarely is it heard in the world of men!’105 Like the reported success of The White-Haired Girl, the popularity of Five Golden Flowers was partly attributed to music that appealed to an international audience despite linguistic differences.106 A shared cinematic language emphasising the intelligibility of music and the corporeality of screen acting was constructed and propagated to foster mutual understanding between ideal domestic and international audiences that shared a proper international subjectivity.

The propaganda state’s cinematic experiment encompassed an ambitious vision of internationalism. Its reach spanned continents from the socialist bloc to Asia, Africa and Latin America. The cinematic experiment was an aesthetic experiment as much as it was a political project in nation building and creating an international order on the world stage. Chinese cultural authorities were heavily invested in testing what cinema could be: its emancipatory potential in calling for collective action, rousing revolutionary sentiments and liberating newly decolonised countries from their colonial past. Investing in a potentially socialist vision of internationalism and developing an anti-colonial rhetoric of solidarity were the means by which Chinese cultural authorities remapped world cinematic space, shifting from the discursive position of cultural marginality to that of a competing cinematic centre.

Chinese film journals open up a neglected international dimension on the study of Chinese socialist cinema, in which national and international characters are closely intertwined. As a form of advertisement, mass persuasion and a site of knowledge production, where information was disseminated domestically and internationally, Chinese film journals offered a self-representation of Chinese socialist cinema as a revolutionary cinema. The sheer breadth and diversity of the films introduced in Chinese film journals demonstrated belief in collective strength in numbers. Extensive coverage of film festivals, film theories and films from abroad constructed an international worldview, a community and an identity that were revolutionary and anti-colonial, articulating the potential for a worldwide socialist revolution.