Unarm, Eros, the long day’s task is done . . .

William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra

Five weeks after he left the Army, Mayne was in Montevideo, awaiting the arrival of Mike Sadler and John Tonkin. By signing a two-year contract to work in Antarctica, he had deferred a long-term career decision; he had also opted for a further period in the comradeship of men rather than family or wider society. It would be a life lived very much in the open, in an inhospitable environment. Whimsy may have prompted his decision, but he was giving himself time to think; he was returning to a wilderness – this time to a snow desert; and he intended to write.

In a letter to his mother, Mayne said that he had been offered an interesting job, but his letter revealed nothing about the nature of that job. Omitting detail may have been a continuation of wartime practice; it may also have been because, in some quarters, it was felt a degree of secrecy should continue to surround what the UK was doing in Antarctica, for the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey was more important in terms of its political and strategic purposes than its scientific ones.

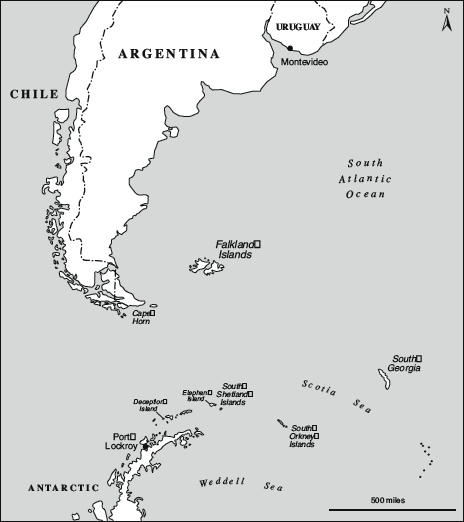

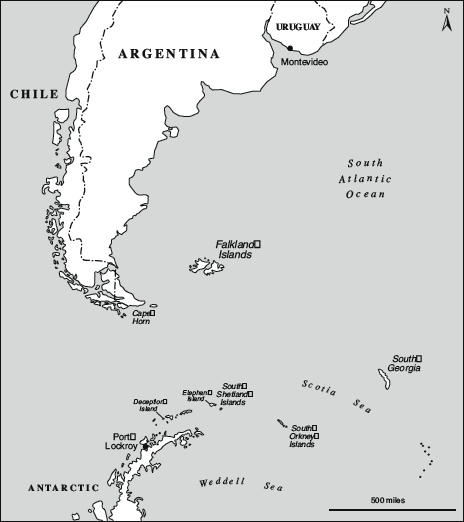

Antarctica was of strategic importance to Britain in time of war. The area had been the scene of naval encounters during the First World War, and continued to be important in the Second World War for the control of shipping lanes around Cape Horn. But, in addition, Britain had an issue of sovereignty over what were then called the Falkland Island Dependencies (now South Georgia, South Sandwich Islands and British Antarctic Territory) against competing claims from both Argentina and Chile to parts of Antarctica. Political developments in the 1940s in Argentina in particular were of concern to Britain lest that country take control of the southern side of the Drake Passage. To forestall these countries setting up bases in areas that were considered important to British interests, in 1943 the government inaugurated Operation Tabarin.1

An inter-departmental expedition committee was set up, drawn from the Colonial Office, Admiralty, Foreign Office, War Transport, Crown Agents and a section within the Colonial Office which was studying biology in the Southern Ocean. Operation Tabarin came under the command of Cdr Marr RNVR. The intention was to establish a number of bases. During 1943–4, Base A was set up at Port Lockroy and Base B on Deception Island; the following year, these two bases were restored and a third, Base D, was set up in Hope Bay in northern Graham Land. When Cdr Marr had to return to the UK in early 1945 due to ill health, his replacement, Capt Taylor, was provided by the Army. But with the end of hostilities in 1945, Operation Tabarin was renamed the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey and came under the command of Cdr Bingham RN. His orders were to restore these three bases and, as top priority, set up a new base on Laurie Island. He was also ordered to place depots in unoccupied Sandy Fjord Bay on Coronation Island, on Argentine Island and Debenham Island. Finally, he was to establish a base in Marguerite Bay on Stonington Island.

There were competing interests, however. The group who had gone to Base A in 1943–4 found a metal Argentine flag left by the ship Primero de Mayo a few months earlier. Confirmation of what the survey could expect by way of political intent on the part of other countries with an interest in the region appears in Cdr Bingham’s final report. He revealed that in the year following the survey’s arrival both Argentina and Chile sent expeditions to establish bases. Shortly after the survey set up a base in Admiralty Bay on King George Island, a Chilean ship arrived with an expedition and found themselves forestalled. Similarly, when an Argentine group landed at Port Lockroy they found an ‘occupation party’ of two men already there, forcing them to move to an alternative area which Bingham, in his report, wrote, ‘can, I think, be considered to be in a most unsuitable place, and of little political and less strategic importance’.2 He also confirmed that when these expeditions landed they were being challenged by the survey. In his opinion the Chileans and Argentinians had put up ‘an opposition show’ to test the reactions of the survey. But the scale of these countries’ expeditions was larger than that of the UK Survey: the Argentines mustered six ships, and the Chileans a frigate and two transports.

Falkland Islands Dependencies 1945–6

So at the end of the war, the UK’s strategy remained as it had been: asserting its sovereignty over these territories but shading the emphasis of its purposes from the military connotations of the Operation Tabarin expedition to the claims of science. This was also a useful device, because there had been two strands of British interest in Antarctica since the beginning of the century. The Scott and Shackleton expeditions represented the imperialist strand of British interest, and the lesser-known Scotia expedition of Bruce represented scientific interest. Hence, in late 1945, the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey was a quasi-military group of some thirty members, part service personnel, part civilians, commanded by a naval officer who was a surgeon-commander with experience in the Antarctic and a second-in-command who had commanded 1 SAS; as well as surveyors, geologists, meteorologists, some carrying out general scientific work, telegraphists and two other former officers of the SAS.

Most of the expedition’s members and all its supplies were to converge by different ships on Montevideo. However, Bingham and Mayne travelled by air.

Airline schedules were skeletal immediately after the war and Mayne’s route took him via Portugal, West Africa and Brazil to Uruguay, where he arrived on 8 December. The first ship carrying personnel and supplies for the expedition, Empire Might, was not due to arrive until 17 December. The British Embassy facilitated local organisational affairs, so Bingham and his second-in-command were able to enjoy an indolent few days, though Bingham, shortly after their arrival, suffered from a bout of tonsillitis and took to his bed. And Mayne, in his hotel, on Saturday 15 December, following what would have been standard practice on explorations and expeditions, began to write a journal. It is probably the longest sustained personal record-keeping that he undertook. Coming as it did within months of the end of the war, it is of considerable interest.

Very little is known about this period of Mayne’s life; and in the only book where it was dealt with – almost entirely from hearsay – the account turns out to be fantasy.3 The greater part of what has been written about Mayne over the years is based on anecdotal reports. There are problems, however, with relying too heavily on this approach, particularly in the case of someone of his status and stature: for one, there are inconsistencies, and respondents may also have an agenda; and in our society, an aura surrounds the warrior hero which tends to generate hyperbole. Here, in his journal, Mayne wrote with insight about others and himself, providing a touchstone against which some of what has subsequently been written about him can be tested. It is written in an informal style, for the most part, and its syntax reflects the speech patterns of his part of Ireland.

While Mayne wrote his first entry on 15 December 1945, he chose as the starting point for his thoughts the Sunday at Chelmsford when he left the army. He briefly summarised the intervening weeks: he had had a week at home, then he flew first to Portugal then via West Africa to Natal in Brazil, where he stayed for a few days. Something occurred there that stayed with him. He had gone to an open-air cinema, but he felt that the film was not very good and so he, ‘spent most of the time watching Orion. He looked just like an old friend, even though he was upside down with Sirius higher than Pleiades.’4

On 26 November, in Natal, Mayne wrote to one of his former soldiers, Billy Hull. Hull had been his most recent driver in the regiment, and he also came from Newtownards. He had asked Mayne to help him obtain the let of a property in Newtownards, which was owned by the Mayne family. In his letter, Mayne reassured Hull that he had enquired about the legal position concerning the house and advised him what next he should do. His letter shows the continuing commitment that Mayne felt to those who had served under him and who requested his assistance, for he did not leave matters there: he gave Hull his address with the survey lest further follow-up was required.5

From Natal he went south in Brazill and had several days in Rio de Janeiro, sightseeing and swimming, before arriving in Montevideo. It was a time for rest and recuperation and his journal records the trivia of a lazy few days. Mayne relaxed, went swimming – one day he stayed too long in the sun – and in the evenings dined and socialised with members of the British community. He had drinks in the English Club with Peter Swan, the Press Officer at the British Embassy. After war-ravaged Europe, he contrasted the South American lifestyle when he took Pirrie Geddes out to dinner at Las Palmas: ‘melon and ham tournedos and strawberries with lashings of cream. They certainly do feed themselves well in this country’. One Saturday night he wrote, ‘I ate the largest steak I have ever seen, or at least ate most of it. It weighed about two pounds, a snack as far as the Uruguayans are concerned.’6

Mayne anticipated the arrival of his two colleagues from the SAS, and he planned the kind of welcome for them that would have confounded some of those who have written about him in the past:

I haven’t yet regretted signing on for this business. I’m looking forward to seeing Sadler and Tonkin again. They are due on Monday. I have arranged a party for Tuesday night. Pirrie is finding another couple of girls. I imagine we will probably still be here next week.

Bingham has recovered from his tonsillitis. He got up yesterday, celebrated his return quite successfully, or appeared to have when I saw him last night.7

The writer of these words had been the commanding officer who, months or a year earlier, had objected to having women at a party in the mess. However, his perception of the dedication that was required from each individual if the unit was to function in war was not motivated by misogyny, as we have already seen. But many have made this wrong assumption. It is perfectly clear from the early pages of his journal onwards that he appreciated the company of women. On two occasions Mayne wrote about someone called Eileen, who may have served on the Embassy staff. In the first reference to her he simply put it, ‘started to think about Eileen’, and in the second, ‘Eileen looked very well this morning’. On another occasion he had lunch in the home of a Briton who had a Uruguayan wife; also invited was someone whom Mayne described as ‘a most amazing-looking Englishwoman’. But, in addition to her looks, he thought her lack of sensitivity to the feelings of others worthy of note, for he wrote that she proclaimed that ‘the food was so pleasant that Lucy, the wife, might almost be English’. She continued categorising throughout the meal, asking finally, ‘if the pudding had been tinned by Swifts?’

On 17 December, Mayne learned that the Empire Might would not now arrive, it was said, until Friday, so ‘I have cancelled the party I arranged for Tonkin and Sadler.’ But he assuaged his disappointment that night. Mayne’s journal gives proof (as it were) that, in terms of the two groups that life-insurance companies divided people into at the time – those who were teetotal and those who took ‘an occasional refreshment’ – he was firmly in the latter category, for such was the degree of refreshment he achieved that, when he picked up his pen to record his thoughts in the early hours of the morning, his writing became completely illegible. It is as though he wrote in snatches over some hours, because towards the end it becomes legible. While his psychomotor skills were severely impaired, he had reached the point where the imbiber experiences great lucidity of thought:

It is 4 o’clock now I am blathering somewhat by my sobriety.

How do you prove that you are sober?

It is about time everyone went to bed.

I am the only person who is not asleep.8

Then he went on to make an eloquent case for drinking. Acting as solicitor for the defence, he put forward the prosecution’s case for drinking only in moderation, then countered it with the argument for immoderate drinking – but with a caveat. First he asked the question, ‘How do you become a sensible person who drinks merely when there is reason?’ Then he delivered the response, ‘Why shouldn’t you drink as long as you are not a NUISANCE. A bad thing if you get pickled; you shouldn’t.’ And, having disposed of the argument, his final statement simply reads, ‘Started to think about Eileen’.

But in his sobriety, Mayne gives insights into his kind of drinking and his attitude to it. Agnostic he may have been, but behind that lay a Presbyterian moral rectitude and concern about public propriety; for he monitored his drinking. On one occasion he recorded ruefully – admitting it required five asprins to cure his headache – ‘Five gin and tonics and one gin and vermouth is overmuch before lunch.’ At 5.25 a.m. on the last Wednesday before Christmas, regretting the excesses of the night before – though his concession to abstinence would not have impressed a liver specialist – he wrote, ‘I’m only going to drink beer until I leave these South American shores.’ Later, he thought better of that undertaking. After Tonkin and Sadler had joined the group, and each member of the survey had been allocated to one of three ships for the first leg of the trip south, the night before Sadler was due to sail, Mayne went round to Sadler’s hotel, the Florida.

We left there about 4.30 and unfortunately instead of having a spot of sleep started talking and drinking with O’Sullivan until 7.00 when we went round to Las Palmas where I had some more gin and then on to the Swans, cocktails and lots too much whisky. I wasn’t sober. Went into town and talked and drank until Sadler went aboard at 6.00. Much too long a day.9

However, it was not simply hangover-induced guilt that prompted those thoughts, for he recalled, when at home four weeks earlier, a ‘usual unfortunate Saturday’, and another time referred to a memorable spree six years before, of which he had but a hazy memory. While Mayne undoubtedly had a high tolerance level, his drinking was social, not solitary. He was not dependent on it; and he certainly anticipated a drought when he signed a two-year contract to work in Antarctica. His last reference to drink was written on 27 December; for the next two and a half months there was none.

On 18 December, the day after his binge, he revealed that he was suffering from the effects of an injury that had been sustained years earlier.

Incidentally, walking around Las Palmas my back didn’t hurt me. I felt that I was missing an old friend; knew there was something wrong. A doctor would probably diagnose it as still anaesthetised.10

It was when he was in Italy that Mayne, in a letter home, had referred to treatment for a back injury. His sister Barbara, a nurse, wrote back in some concern, but, replying on 20 October 1943, he played it down, and, of course, he did not reveal the problem to anyone in the unit. When and how the injury happened is unknown, but it was a chronic condition that got progressively worse during the following two years.

In his journal entry of that same day, 18 December, there is an arresting statement. Mayne recorded that he intended to write a novel in Antarctica, which he was entitling ‘The Growth of a Unit’. That he intended to write at length is not surprising. He had written up the unit’s war diaries and reports since the days of the Special Raiding Squadron. But his choice of title, ‘The Growth of a Unit’, is interesting: it has a resonance with both the title of the chronicle of the unit, ‘Birth, Growth and Maturity of 1st SAS Regiment’, and the final chapter of Pleydell’s book Born of the Desert, which is subtitled ‘The Growth of a Unit’ and deals very briefly with the period after Mayne took over. Now, Pleydell’s book was published by Collins in 1945, so Lt Col Ian Collins at Airborne Headquarters would have known of it and would certainly have discussed it with Mayne. Then again, Mayne and Pleydell had corresponded, so Mayne’s provisional title was no accident. However, his decision to opt for the novel form rather than a historical account of the development of the SAS is more surprising. He did have the chronicle in his possession (whether he took it with him for this expedition is unknown), and it gives names, dates and reports of significant operations, and so he could have attempted a first-hand account. But the choice of the novel form allowed him a distancing device. Mayne was not self-serving in his written and oral accounts of action; on the contrary, he was laconic, self-effacing, and played down his own importance. This was not false modesty: for example, in his journal, which he wrote simply for himself, he recalled his short leave at home after being demobilised. On the Saturday, he had ended up in the Belfast Arts Club where, he said, the President had welcomed him. He described his feelings in one word: ‘embarrassing’. No, an autobiographical account was not his style.

Pleasant as those early weeks were, Mayne was keen to get underway, and he was looking forward to the experience. Before the other members of the expedition arrived, he wrote of two stories he had heard which amused him: one was by a Jimmy Scott, about huskies eating their traces; another was by Bingham, about the care one must take in selecting the books to be taken out on sledges (as to the texture of the paper), because nothing was to be wasted. Huskies from Labrador had been brought to Antarctica and used successfully the previous year in north Graham Land, when Base D had been established, and Bingham had played an important part in their acquisition and training.

On 20 December, the first of the members of the expedition to arrive disembarked from the Trepassey and a theme began to emerge in Mayne’s journal which has recurred throughout this book: his assessment of others. Shrewd judgement of people is often considered to be one of the characteristics of a successful leader; a characteristic that is, of course, associated with leadership in a wide range of activity, and not at all confined to the military. Mayne’s views in the journal are particularly interesting because he was in a transition stage from the SAS to the survey; he would have to make adjustments, accepting and working with personnel in whose selection he had played no part:

Trepassey arrived this morning, Slessor and O’Sullivan aboard plus fifty-four dogs and eight puppies.

They both seem pleasant, different types. Slessor looks about thirty-two or three, doctor, spent four years at the Rotunda [hospital], comes from Aberdeenshire, looks painstaking and is temperate.

O’Sullivan just a youngster, good-looking in a typically Gaelic Irish way, quite talkative and probably not so temperate. O’Sullivan with us for lunch and Slessor for dinner.

On first impressions I would quite like them to be at the same base as myself.

Empire Might and probably Paraguay will arrive tomorrow.11

Surgeon-Lieutenant Stewart Slessor and Sub Lt Tom O’Sullivan had earlier been sent to Labrador to obtain the huskies and bring them back for the expedition.12 It is interesting that although Mayne rated Slessor as temperate, he was happy that they should both be at the same base, so the whisky test for officer volunteers for 1 SAS (if indeed it was administered) was not designed to reject non-drinkers.

However, their arrival gave Mayne an opportunity to observe Bingham operate as the leader of the group. Until now, during the waiting period, their relationship had been relaxed and informal. They had socialised together, and both were from Northern Ireland, though their service background was very different. Bingham was a surgeon-commander and his man-management experience would not have been as extensive as that of a commander coming up through the seaman branch. Mayne, on the other hand, was not a career officer, but he had the greater leadership experience. On that first occasion, Mayne observed Bingham relating to the two survey members and, very insightfully, he began to make his provisional assessment. From what we have seen, Mayne was considered to be an excellent leader, both by his soldiers and his superiors. But his leadership attributes were not simply instinctive: he had observed and analysed. It becomes clear, for example, from what he wrote that Mayne did not subscribe to the leaders-are-born-and-not-made school of thought. Styles of leadership, in his view, could be cultivated.

The qualities that he felt were important in a leader were: integrity, self-confidence, sensitivity for concerns of others, flexibility of thinking and the confidence to trust others’ judgement. But the whole process and the way the elements were put together he considered an art. Mayne began to assess Bingham:

The Commander gives me the impression he might be, in a way, difficult to work with; that he might think that no one can do a job properly except himself and that the old way of doing things is always the best. I hope I am wrong, for he is a very pleasant person. He lacks guile. I am not certain whether that is a good or bad thing. He does not lack self-confidence. He is, I am certain, a very honest man.13

Mayne went on then to make a brief contrast with David Stirling – perhaps one of the very few records there are of Mayne’s views on Stirling. A shortcoming about Bingham as a leader, in Mayne’s eyes, was that he did not have the ability of ‘making you think you are a most important person. Stirling was a master of that art and it got him good results.’

Concluding his provisional assessment of Bingham, Mayne noted two other characteristics which were important in his reckoning:

I don’t think he is a good listener. I hope he is not indecisive; at times he tends to make me think he is, in that I always seem to have to hang about when we are leaving somewhere, or especially some person. That of course is no criterion, probably very different when there is something to be done in a hurry.14

Sadler, of course, at the time had no idea that Mayne kept a journal. Fifty-six years later, reading what Mayne had written about Bingham, Sadler commented, from his experience of working with the Commander:

I think he could listen but I don’t think he wanted to, because I think he had a theory of command and how you retained command in the naval manner. Whatever you asked him he said, ‘I’ll tell you in good time.’ And he didn’t. I think he was frightened that people would argue with him and he would lose his authority.15

Spare a thought for Bingham though. If, as Sadler suspected, he needed the security of rank to sustain his authority, as commander he could have faced the scenario for a nervous breakdown; for he had as his second-in-command someone who, according to all accounts written since 1958, had floored a superior officer – and there would be no provision for close detention in Antarctica. Bingham, however, almost certainly lost no sleep on that score; for in 1945 the legend about Mayne had not developed to the stage it reached in later years.

No, it was not Bingham who had difficulties; it was Mayne. He would have to adjust to being in a subordinate position on the expedition to Antarctica. And that Thursday morning of 20 December, as he watched Bingham relate to Slessor and O’Sullivan, Mayne reflected on himself. How would he, after having commanded a unit of the calibre of 1 SAS, live with this situation? What comes through, when he considered his new role, is self-awareness and humility.

My own position is simple enough, at least I hope it is. I am not certain just how good I will be at being an underling, but I can be lazy enough to enjoy it, or possibly to tolerate is a better word. I don’t think anyone no matter how lazy could enjoy it. What I will find difficult is not having my opinion asked; not that so far anything has cropped up on which I am sufficiently versed to give a considered opinion. I have no intention of putting forward any suggestions without being previously asked. Better all round if I didn’t.

This is the gloomy side of the picture. I am prepared – and hope – to find myself completely wrong.

In my opinion Slessor and O’Sullivan have done a very good job with the dogs: they merited a little more praise, I believe, than they received – remembering that this is the first time I have ever seen huskies. As little knowledge as the curate, who on the return from his honeymoon and asked if he had found everything all right replied, ‘Yes, but isn’t it hidden in such a cute fashion.’16

So relating to the leader of the expedition presented no insuperable problem; but there were other personnel. Mayne had had no say in their recruitment; he had no expert knowledge in any of the fields that they represented. Nonetheless, all the various specialisms would have to be subsumed for much of the time: general teamwork would apply for the creation and maintenance of bases. Huts had to be erected; supplies from the vast logistical exercise providing materials for accommodation, supplies and fuel had to be manhandled. Sites would have to be found for new bases and the whole enterprise had to be undertaken speedily within the austral summer; and in all of that, interpersonal relationships would be stretched to the limit. As the ships with the personnel and their supplies began to arrive at Montevideo, Mayne’s rigorous sifting and categorising of individuals went on. The basis of his assessment was on character. The qualities which he tolerated least in individuals were conceit, a sense of self-importance and crudity. He had a meal with one of the newcomers and assessed him: ‘It was on the Sunday night that Walton ate with me; he is insufferable, practically, with his conceit in his knowledge; an annoying type, he appears to consider himself most important.’ Of another, he wrote, ‘Salter, a bearded meteorologist is a bore, considers himself important.’ A third he wrote off as ‘a crude little cockney’.

At some point, for there is no date alongside, Mayne wrote a jingle that occurs in its final form at the back of his journal. It may have been intended for the book he planned to write about the unit, because it turns out to be his bowdlerised version of a bawdy song the officers of the unit sang in the mess.

As I was walking down the street,

A fair young maid I chanced to meet,

A Piccadilly bint she hawked her wares,

With shimmying hips and golden hair,

She said, ‘Will you come and share my flat,

Shed your coat and hang your hat?’

I thought of the words of my mother dear,

And the words of love I would never hear,

But I went with her and she taught me much

Of the art of love and the magic touch,

She talked to me of the life she had led,

Of sleepless nights and days in bed,

Now that is the life that is meant for me,

The wine and the women and the laughter free.

When Sadler saw it over half a century later, it rang a bell with him.

This reminds me of a song we used to sing in the mess. It has been rearranged; that is very much the gist of a song we used to sing. He certainly based it on another song. It doesn’t go quite the way I recall it. He may have rewritten it to amuse himself I think. It was too coarse a version for him. He was very anti anything vulgar.17

But it is interesting that while he was against sexual crudity, and therefore tamed the obscene version they used to sing, he kept its erotic edge.

The expedition was divided into three groups for the first leg of the journey, from Montevideo to Stanley in the Falklands. As second-in-command, Mayne noted personnel, their specialist area and their departure. On 21 December, the first ship to leave was William Scoresby with Salter, meteorologist; Mason, surveyor; Joyce, geologist; Butler, signaller; Cummings, signaller; Crutchley, signaller; Francis, surveyor; and Featherstone, meteorologist. The remainder of the expedition spent Christmas in Montevideo. On Christmas Eve, Mayne dined with Tonkin and Andrews at Merinis after ‘a pleasant spot of singing in the English Club’. He returned to the club afterwards with O’Sullivan, until O’Sullivan went to Mass, and he then went round to Sadler’s hotel.18

On 26 December, Trepassey sailed with Slessor, O’Sullivan and Sadler, as well as Stock, signaller; Croft, geologist; Hardy, meteorologist; and Choice, meteorologist. Mayne was anxious to be under way. He had heard that some of their stores were on the Peldie, which was not due until 6 January 1946, and they were trying to find out whether these stores were important enough to hold them up until their arrival. He did not want to spend another nine or ten days in Montevideo. Most of it he enjoyed, he wrote, but if they were delayed until 6 January, he would have been there a calendar month. Since the vast exercise bringing the component parts of the expedition had been orchestrated elsewhere, he and Bingham had little to do until the stage after leaving Stanley for Antarctica, and as the weeks passed he found that doing nothing was very boring. In the event, however, at 11.30 p.m. on Sunday 30 December 1945, the third group of Bingham, Tonkin and Walton, along with Small, signaller; Freeman, surveyor; Andrews and Mayne sailed out of Montevideo.

Then the unexpected happened. On the voyage to the Falklands, Mayne’s spinal injury began to give him severe pain. Now, he had suffered pain with it for at least two years, but this was different. Two weeks elapsed between the journal entry in Montevideo and his next on 11 January 1946, during which he had been examined by two doctors in Stanley: Doctor Slaydon, who was probably based in the hospital there, and Slessor, the survey’s doctor. Mayne recorded the outcome:

My back started getting much worse on the way down to the Falklands, hurting me at night. I tried it out pretty strenuously when we arrived there. It lasted the first day all right, but on the second it went badly. Agonising. Slaydon and Slessor examined it and advised me not to come down. Talked of paralysis and serious trouble, so I am going home. It is still hurting me quite a bit. I think the movement of the ship causes a lot of the trouble.19

This development, however, did not necessarily mean that Mayne would be unable to fulfil his contract with the survey. One option was to go to the UK for treatment and return to the expedition the following year. Another turned up unexpectedly when he was in the Falklands. He and Bingham, with the remainder of the third group, arrived off Stanley late on 3 January and went alongside the following morning. Mayne and Bingham stayed at Government House during the five days that they were there. Mayne wrote, ‘a pleasant old soul the Governor. I enjoyed our stay.’ His Excellency the Governor was not only a pleasant old soul, he was also quick-thinking. Reacting to the medical advice that Mayne should not continue to a base in Antarctica but undergo treatment, he offered Mayne a job in the Falklands.

As they sailed from Stanley in the early hours of 9 January 1946 and headed for Fox and Goose Bay, the choice uppermost in Mayne’s mind appeared to be completing the assignment, because the following day he had an opportunity to discuss matters with Sadler:

Talking to Sadler for a time yesterday; difficult to know what to do when all this is over. He will be twenty-eight when he comes back, I’ll be thirty-three. I am not particularly worried. The Governor’s offer of a job in the Falklands did not attract me overmuch.20

Until he read those words in 2001, Sadler had no inkling of Mayne’s problem, because during the war Mayne had not revealed it in the unit. Reflecting on their time with the expedition, Sadler recalled, ‘I thought at first – at the time – that it might have been a diplomatic pain, that he couldn’t stick Bingham, but that might be wrong. He was obviously in much worse pain than I thought he was.’21 However, Mayne had no need to come to a decision immediately. A quick return to the UK was not possible anyway: the allocation of groups to their respective stations had to be completed, and he would have to return by one of the survey ships (bringing back returning members from Operation Tabarin). They continued south. Their destination in Antarctica was Deception Island, Base B, between the South Shetland Islands and the continent of Antarctica.

The first two days out from the Falklands were calm, but as the ship got well into the Drake Passage, the temperature got much colder and the sea became boisterous. The pitching and rolling of the ship did not do much good for Mayne’s back and on the night of 11 January, he recorded that he had scarcely slept with the pain he was suffering. In other respects, he was a good sailor and suffered the effects of sea sickness less than the two colleagues, Freeman and Small, with whom he shared a cabin. Of Small he wrote, ‘I like him, young but amusing and pleasant. I like good manners in people.’22

In the knowledge that he would have to return home, Mayne appears to have felt fairly relaxed about the dislocation of his plans. He may have viewed his situation as he would had something similar happened during the war: delayed admission to hospital for treatment, followed by convalescent leave and return to unit. Certainly, judging from his journal entries, for about ten days after Doctors Slaydon and Slessor examined him, such seems to have been his reaction. And the interest that he showed in the beginning in anticipating living in the South Polar Region was maintained.

As they headed further south, the temperature fell below freezing and there were snow showers and periods of sunshine. Choosing his moment, he photographed some icebergs. Throughout his time with the survey, Mayne’s journal shows that he responded with sensitivity to his surroundings. On 11 January, he noted that he had seen a whale and, the following day, his first iceberg. Then there were whales blowing and ‘lots of penguins bumping through the water’. Although his back was giving him a lot of trouble, he tended to be optimistic each day: ‘I hope I don’t notice it so badly tonight.’ But two days later, he recorded that he had wakened with a most annoying headache, which he associated with his spine and pressure on a nerve. He came on deck as they were passing Cape Melvin on King George Island and witnessed, he said, a terrific sunrise.

On 13 January they reached Deception Island and the ship worked its way round to the entrance: Mayne described Deception Island as being formed from an extinct volcano whose centre provided an excellent harbour. There Featherstone and Crutchley disembarked along with their supplies. Then the ship headed further south for Port Lockroy, Base A, where Hardy and Stocks were to be based. To each of the bases, Mayne wrote, two Falkland Islanders were also assigned. On 17 January, he took a photograph at 1.30 a.m. before they left Lockroy, heading for Louise Island and then Laurie Island. As a base he preferred Lockroy to Deception Island: it was cleaner, whereas there was a lot of lava at Deception Island. They were making first for Louise Island, where Base C was to be established. On 19 January, passing the black basaltic cliffs of Elephant Island, Mayne recalled Shackleton’s party’s survival there and the epic journey Shackleton and five companions made to South Georgia to bring rescue:

Saw seven or so whales yesterday and also seals on the ice. Today we passed Elephant Island where Shackleton set off for South Georgia from. I would have liked to have gone ashore and seen if anything or any relics remained of his party’s stay.23

Mayne may have read of Shackleton’s expedition, but there were more direct links. The first leader during 1943–4 of Operation Tabarin was Cdr Marr, who as a young man had been one of Shackleton’s team on the Quest expedition, so there was a local tradition of knowledge. So when Mayne wondered if there would be any evidence or relics of the party’s stay on Elephant Island, what he had in mind were traces of the most fundamental means of support that they had been able to take with them for their survival – sledges, implements and tents. The party had had to survive for about ten months in some of the most inhospitable conditions on the globe. Shackleton’s strength of character was critical in imbuing the will to survive, and his great care for his men was well known. His was a kind of leadership that Mayne understood. Indeed, there are parallels in leadership between Shackleton and Mayne: each was an inspiration to his men; each, subsequently, became an inspiration to others for decades.

Earlier that day, 19 January 1946, as they were making their way towards Laurie Island, Mayne reviewed his shorter-term options:

I am then half-thinking of transferring to the Trepassey and going round to Marguerite Bay with her. Doing that I couldn’t be back to Stanley until some time in early April. It might be quite pleasant to travel on with her up to Newfoundland and cross from there home. Except at night, my back isn’t too bad. I put some Elastoplast on yesterday to see whether or not it would help.

If I went that way I would probably be home some time in June, go straight to hospital and be home in July, take two or three months convalescent leave and then decide what to do, either to come out here again or to settle down in some job.

Coming out here again all depends on what party I would be with, or rather what personnel would compose the party. I wouldn’t stay at the same base as Walton. He is about the only one who would be left who really gets my goat.24

Mulling it over, Mayne debated the pros and cons of opting to return to complete his contract. At this stage he took the optimistic view that hospital treatment would cure his back problem and allow him to keep his options open. On the side of returning to the South Polar option, he constructed a best-case scenario:

People I would like to be with are O’Sullivan, Small, Tonkin, Sadler, Hardy, Slessor and Featherstone. To be with people like that, I would willingly come out. A decent geologist and the present two surveyors, Mason and Freeman. That would leave out from E Base Walton and Salter. About either I can’t visualise many tears being wept. I don’t know whether Bingham would be staying or not.

I could spend a very happy year with that crowd. One objection to it is that the whole lot would be coming back home at the end of the two years, but that would not be insurmountable. The new people at D would have had a year’s acclimatising for it.25

As far as he was concerned, returning was a serious option and, after all, his original reasons for choosing to go on the survey to Antarctica were unfulfilled. The drawback would be that the two-year contract of the others would be completed; his would have one year to run.

The other element that influenced Mayne’s thinking was, of course, Cdr Bingham. But to what extent? As we saw earlier, Mayne’s provisional assessment of Bingham, as they spent time in Montevideo, was balanced. Basically, he found him pleasant and thought that he was honest; but against that, perhaps inflexible, timorous about trying out innovation and lacking insight into himself and others. Bradford and Dillon’s version of this period had Bingham laying down the law to Mayne about who was in charge. But Mayne’s journal shows that this is fanciful.

Mayne mentioned Bingham little after that first assessment on 20 December – only that they sailed on the same ship to the Falklands and both stayed in Stanley at Government House – until 13 January.

Bingham mentioned that he thought of taking Walton to Base E; it is his business, but the combination of Salter and he will be hard for Sadler to stand.

I cannot quite assess Bingham. I have been doing my best to put a good word in for him on every occasion: the chaps are all prepared to like him. I hope he doesn’t behave like a schoolmistress with a crowd of kids out on a picnic.26

So, although Mayne had expressed reservations early on about how good he would be at playing the underling, he fulfilled his role as a loyal first lieutenant and was consistently supportive of Bingham. Then, on 19 January, six days later, Mayne came back for the last time in his journal to Bingham, and in penetrating detail. Mayne anticipated seeing him the following day, 20 January, at Laurie Island.

It would help the party as a whole if Bingham kept them better posted about what is happening and what would be likely to occur. If I can, I will persuade him to tell these chaps that they will be at other bases next year. Incidentally I was forgetting about Choice and Joyce. Choice might also need to be moved to D, need three more ‘met’ [meteorologists] people to come out.27

But something happened unexpectedly which was to mean that Mayne did not get the chance to meet and speak with Bingham.

Mayne’s entry for 19 January 1946 is lengthy and was written on two separate occasions. There is no indication when he wrote the first section, but he began the second part at 10 p.m.

At 8.30 tonight we turned back towards Stanley. Why, I don’t know; we would have been at Laurie Island tomorrow after midday. A confounded nuisance, I hope it doesn’t make any radical difference to Base D being established. Stops me going on to Marguerite Bay and to Newfoundland; may be better as far as my back is concerned, but I wasn’t going to worry about it.

It seems damned stupid turning back now when we were only another day’s steaming away, less than another day. I had wanted most of all to see Bingham again and try to fix up a decent party for next year. No way of getting in touch with him, letters won’t reach him in time.28

The strongest terms used in Mayne’s journal, ‘confounded nuisance’ and ‘damned stupid’, preface his wish to see Bingham the next day to discuss allocation to bases the following year, so returning to complete his contract was certainly still an option. However, he accepted the new situation and took stock of its implications:

I suppose I will probably be home some time at the end of March. Stanley next Tuesday, that is the 22 January. Leave the Falklands about the 14 February; Montevideo by the 18th and then it depends on how soon we can get ship and how quickly we get back. If it is a meat ship from Buenos Aires, it shouldn’t take more than, I don’t know, in a month I suppose. At any rate I should be out of hospital by the end of April. I wish I knew what I really wanted to do. I could enjoy a couple of months at home, taking things easy and doing a bit of work about the place, though everything I can think of involves a lot of twisting and straining of my back.29

Mayne then returned to Bingham and made an assessment of his own attitude and Bingham’s leadership qualities:

If Bingham wasn’t staying down next year I believe I would be keener to return. But probably in any case by this time next year he will have got over the first flush of being in command. It wouldn’t take very many changes to make him into a good leader, or rather an excellent leader. At the moment he hasn’t got everybody’s confidence, he is bad at explaining what he wants done and what he intends to do. He also has a bad habit of talking too much to outsiders.30

Had the above assessment been given to Bingham by his superior at an appraisal interview – and subsequently reviewed at a higher level – it would not have been considered destructive. However, according to Sadler, Bingham did not change and continued to overcontrol and behave as a manager rather than a leader. Five years later, in a letter to Peter Swan, Mayne wrote a postscript, ‘Ted Bingham is at the naval depot in Londonderry. I haven’t seen him and I am not particularly keen to do so as I am afraid he bores me.’31 So in retrospect, his feelings about Bingham were in the category of low-level irritation rather than fundamental antipathy.

But on the night of 19 January 1946, turning his mind to the present, Mayne was more interested in his surroundings.

I am sorry I didn’t get a photograph of Trepassey with her sails up. She looked well tonight bucketing through the heavy seas. The spray was freezing on our rigging this evening; before we turned off we had quite a bit coming over. When the wind gets up it makes a great difference in the temperature; yesterday we had a following breeze, about the same strength as our own speed and on the flying bridge I believe sunbathing would have been tolerable and even pleasant.32

However, when the ship carrying Mayne changed course at 8.30 p.m. on 19 January 1946 to cover the 590 miles to Stanley, whether or not he had made the decision at that point, it was to lead to a parting of the ways with the survey. Sadler and Tonkin continued with it; but Sadler found Bingham too inflexible in allocating men to bases and, after an argument with him, left the following year. Tonkin had another close escape from death: he was walking ahead of his dog team when he fell through surface ice, plunged perhaps twenty feet down a crevasse and was stuck fast. He was rescued and the person principally responsible, the man lowered down to reach Tonkin, was Walton.33 Then fate dealt with Bingham in similar fashion to Mayne: he was considered medically unfit to spend another winter in the Antarctic and he went to Stanley. In his final report on the survey – probably written some time in 1947 – Bingham confirmed that the objectives he had been given had been met, but that they had run into some unexpected company with the arrival of an American team on Stonington Island. He questioned the secrecy which surrounded the survey (in comparison with the Americans, who published reports). He also pointed out that both the Chilean and Argentine bases were on a more pretentious scale and more extensively equipped; and he complained about the adequacy of their ship, Trepassey, which had been built during the war and had only land-type diesel engines. It had suffered three cracked cylinder heads during its last tour of the bases. Given the politically sensitive nature of the operation, Bingham chose his words carefully for maximum impact. ‘It would be bad for British prestige’, he wrote, ‘were she to be towed to safety by an opposition expedition ship.’ Then, in a gracious gesture, he put on record the loyal cooperation he had received from all members of the survey, ‘often under exasperating and to them entirely strange conditions’.34

Mayne went into hospital in Stanley on 23 January. He made only two entries in his journal while he was in hospital; both are short. On Friday 25 January he wrote that he was becoming rather bored: he had been receiving radiant-heat treatment twice a day but he felt that it was not doing much good. Bradford and Dillon’s version had him in the wrong country, undergoing the wrong treatment (Buenos Aires for an operation to his back). However, Mayne crossed a watershed between 19 January, when he had pondered the option of returning the following year, and 29 January, when he made his second journal entry in hospital: he had come to a final decision – not to return.

Getting a little bored here. Today I have been mapping out my future career. At the moment my inclination is to find a partner and start off as a solicitor. With or without a partner, no more subservience. I imagine I can always make a living.

Thinking about the letters I must write. To: Bill Irwin, Mrs Hanbury, Poat, Niall Nelson, Williams, Pleydell. I can do them all before I leave the Falklands. Can’t write in bed though.

Haven’t heard any more about the party down south, whether they left the Orkneys or whether they are in Marguerite Bay yet.

Lots of moths in this country, falling all over the bed.35

He did not reveal his reasons for ruling out returning to Antarctica. He may have been medically advised that it would be unwise, or he may have felt that it was just not worth the candle, from the point of view of the changeover of personnel and the short-term nature of the contract. It is clear, however, that, having made up his mind, he did not review the matter.

On 11 February 1946, Mayne sailed on the return leg of the voyage home from Stanley to Montevideo. On 13 February, he wrote his only retrospective comment on two weeks in Stanley: ‘Quite enjoyed my stay in hospital, the matron was pleasant, Joan Treize her name. Wrote some letters before I left to Poat, Mrs Hanbury, Bill Dowie and home.’ The ship ploughed north through heavy seas in gale-force winds for two days; ‘not many parading for meals’, he recorded. He shared a cabin with Ashton and Berry, whom he described: ‘Ashton is a real craftsman, quite pleasant, Berry a typical old QM.’ Here, he was referring to members of Operation Tabarin, who, having completed a two-year tour of duty, were returning home. Ashton was a Royal Navy rating, a carpenter, and Berry was a Purser. They had both been at Base A, Port Lockroy in 1943–4 and had been moved to Base D at Hope Bay during 1944–5. They and other members of Operation Tabarin were going home now that the survey had taken over.

Mayne, on that occasion, also recorded that he was not sleeping much at night: ‘bunk too small and narrow and my leg troubles me then’. Anticipating his return to Ireland, he wondered if he would be home in time to celebrate St Patrick’s Day:

Looks as if we will be home 1st week in March. I wonder will I be in Ireland for the 17th. Last time was 1940, quite pleasant what I remember of it. Stationed at Sydenham then. Lot of everything flowed under the bridge since then.

Possibly be in hospital, more than likely; I will, if I can manage it, go to hospital at home. I would like that, go in about the 20th, convalesce through May and June, have some holidays through July and August; hope for some deer stalking in September and then, I suppose, think of doing some work. A pleasant programme and I am just about due that amount of leave. I wonder how long it will be before they terminate my contract, should get a couple of months out of them after my return to UK.

Would like to get fit again. Had a shock when I tried on some shorts which fitted me two years ago – about three inches of a difference.

They were due to arrive in Montevideo on Friday 15 February but he anticipated that, because of the weather, they would not arrive until the Saturday morning. Then, he went on, ‘Rumour has it we board the Ajax that afternoon. Would have liked up to a week in Montevideo.’ Rumour, on this occasion, was correct.

The battlecruiser HMS Ajax was no stranger to these waters: River Plate had been added to its battle honours for its part in the pursuit and damage leading to the destruction of the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee off Montevideo in December 1939. The connection was re-established six years later when Ajax left home waters in January 1946 with orders to escort a troop ship, Highland Monarch, which was bringing back the German crew of the Graf Spee who had been interned for the remainder of the war.36 Ajax had shown the flag in Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires; on 16 February it sailed to Montevideo, where Mayne embarked; that afternoon it weighed anchor and headed for Freetown in West Africa. The Royal Navy, as one of the progenitors of Operation Tabarin, retained an interest and responsibility for the survey team and was the means of bringing its members home. There were other expedition members on board Highland Monarch and they were to transfer to Ajax at Freetown.

When Mayne boarded HMS Ajax in Montevideo that Saturday afternoon of 16 February 1946, the journal, which he had begun in that same city, came to its logical end. Its purpose was over. In fact he recorded just two more brief entries. The first was on 25 February when he noted that they had crossed the line that morning and that it ‘has been a pleasant trip’. He also said that they were escorting the Highland Monarch and were due in Freetown on 27 February. The last entry is again brief. It is dated Saturday 3 March, and reports that he had had lunch with Capt Cuthbert of Ajax, and commented, ‘Interesting enough’. He wrote that they took on board the remainder of the expedition from Highland Monarch, which was then going to Hamburg. He then began a new paragraph: ‘We have on board here now . . .’ He had reached the foot of a page, so it looks as though the next page is missing. All that remains, towards the end of the book, is the song previously quoted about the girl from Piccadilly.

While the objectives of the survey had been met, the larger political issues, of course, concerning competing sovereignty were not resolved. These were effectively put on hold when the Antarctic Treaty came into force in 1961. The Falkland Island Dependencies Survey then became the British Antarctic Survey in January 1962. A faint echo of Operation Tabarin fading into the Falkland Island Dependencies Survey in 1945 resonated in 2001 when the British Army garrison in South Georgia, which had remained there since British Special Services regained the island from Argentine occupation in 1982, handed over its base to the British Antarctic Survey.37

Mayne’s journal does not illuminate the political background to the survey, but it does have a value that extends far beyond the period it covers. It is important in a number of ways. Most of what others have written about Mayne in the past, both as a man and as a leader, was based on anecdotal reports; there has been very little from written sources and virtually nothing (apart from letters home) from his perspective. His journal of the Falkland Island Dependencies Survey corrects that.

It certainly supports what both Malcolm Pleydell and Fraser McLuskey observed during their respective times in the unit: Mayne searchingly assessing individuals. For throughout his journal, it is the most prevalent theme. He was adamant that he simply was not prepared to work at the same base as Walton; and this is consonant with his reasoning and swift action in leaving No. 11 Commando in 1941 when Keyes became acting commanding officer. Also, the tenor of Mayne’s probing and assessing is consonant with how David Stirling described him at their first meeting: ‘He questioned me rapid-fire style, but always in that gentle, slightly mocking voice.’38 Now, assessing men is an important part of a combat leader’s role – their lives depend on one another, so they have to be trustworthy – but Mayne continued the practice beyond the war. Jimmy Storie served with Mayne when the unit operated in small groups in the desert. He put it like this: ‘He had to like you. If he took a dislike to you, you might as well forget it. If he liked you, you were made for life.’39 But since Mayne made no secret of his contempt for the arrogant, the self-conceited or the crude, they knew it. There can be no doubt that three on the survey knew it. Now, to know you have the unconcealed contempt of a physically powerful man cannot be a comfortable sensation; you would certainly not go out drinking with him. So Mayne made enemies, and it is easy to see how the fear that some had of him – as Sadler related – could come about. And it heavily underlines the problem facing those whose interpretion of Mayne’s character was derived from hearsay.

But equally, the people he wanted to associate with were pleasant, agreeable and considerate. Such people could come from different backgrounds; he did not restrict his friendship to one circle of society; there was the shipwright and the doctor. Mayne’s own qualities appear in his journal; those who knew him well could discern them. As a padre, Fraser McLuskey had no difficulty relating to him.

He wasn’t, he would have said, a religious man. Yet he had a real reverence for God. Because I stood for something he respected, he helped me. It was a wonderful friendship.40

Nor did he set a different standard for women. The appearance of an ‘amazing-looking Englishwoman’ was insufficient to compensate for her feelings of superiority – although he chided her inconsiderateness more subtly than he did the men. From his values and his attitudes, the impression that one is left with is of a very decent man, and a humble man.

Mayne’s journal reaffirms what was already evident from his analyses of field reports during the French campaign – that he was reflective. It illustrates his cognitive and rational side; his writing shows, too, that he had the ability to deal with ambiguity and cope with the frustration of working with a commander whose leadership calibre he questioned. He had clear ideas about good leadership; he believed that successful leadership styles could be cultivated; and, in the case of Bingham, he made allowances for his rawness to a position of command. Moreover, he demonstrated self-knowledge and intellectual honesty.

But the journal reveals more about the man. The extent of the pain he suffered from his damaged spine he had never acknowledged before, so no one knew of it. He referred to it in entry after entry in a matter-of-fact way; it did not dominate his thinking, but it was a severe problem for him. The journal also suggests that Mayne had difficulty sleeping, for many of the entries were made in the early morning. (Sadler’s first remark when he saw the journal’s transcript was, ‘Where did Paddy get time to write all this?’) His inability to sleep would partly have been the result of pain, but not completely. He was often awake and writing without making any reference to his back.

Those who have claimed that Mayne was a misogynist did not know that he had kept a journal during his time with the survey in which he clearly revealed an attraction to and an appreciation of women. The first entry reveals that when he arranged a party for Sadler and Tonkin it was not to be a male rebonding session, but a mixed group, with a local contact bringing two more girls. During the first week in Montevideo, until the weather broke, he went swimming with men and their wives, with the McCormicks and the Swans. He was attracted to someone called Eileen. When he met her he was about to depart for Antarctica for two years; when he returned, he expressed the wish to have had another week in Montevideo. And while Mayne showed contempt for crudity, he himself wrote of matters sexual, though he did so lightly – in his amusement at the other-worldly clergyman’s honeymoon experience and in the jingle of the young man’s sexual initiation. But in his version of the song, he showed that he responded sensitively to women, and he wrote without lewdness.

The journal clarifies the pattern of his drinking. Sometimes he had a binge, if he was in the right company; more often it was social drinking with friends. But he had his standards; for he considered that six preprandial gins were over much. He did not appear to drink because of pain – although he referred to its anaesthetic properties – and he did not tend to drink alone. However, references to drinking are all contained in the short period between 15 and 27 December; the last, ‘Drank some whisky in my room with the Swans, and Bingham afterwards’. After that there is none.

It has often been claimed that Mayne did not want to go back to practising law. But his own words refute that. The steps in his decision-making process are laid out in his different journal entries. First of all, projecting that he would be thirty-four if he returned to complete the two-year contract, he wrote that he was not particularly worried. So at that stage he was flexible; he considered the job offer from the Governor of the Falkland Islands Dependencies, but it did not appeal. A week later, he had been giving the matter more thought: whether to return to complete his contract with the survey or to settle down in some job, though he acknowledged that he did not know what he really wanted to do. Finally, ten days later, he had made up his mind: ‘Today I have been mapping out my future career.’ His decision was to return to the law – not in a subordinate capacity but in partnership: ‘With or without a partner, no more subservience.’ He was definite on that, and he reckoned that he had the skills and ability to earn a living.

But the journal reveals something else about Mayne: not through what he wrote, but in what he did not write. While he began it in Montevideo, its opening entry is set that Sunday in Chelmsford five weeks earlier. Yet, not once in the journal did he allude to his part in the war, nor did he refer to the war directly; there is no backward glance. He allowed himself no anecdote from his military experience; nor did he permit a comment on his war experience in relation to the calibre of personnel he was with now, compared to those in the unit he had commanded. Perhaps in one comment it is implied that he had been in the military: his reference, ‘Berry a typical old QM’. However, avoiding any direct reference to the war was not simply a case of writing a journal focused on the expedition, because he did refer to a prewar incident. In the entry of 19 January 1946, after the ship had changed course for Stanley, he wrote that he had borrowed a pen from a South African meteorologist, Niddrey, whom he had met and had a drink with in Pietermaritzburg in 1938 when he had toured with the British Lions. But he maintained strict control over mind and his feelings concerning the war period. So controlled was he that it suggests avoidance.

He did, however, make four allusions to the war. The first was the image of Orion’s steadfastness as an old friend, which he conjured from sitting in the open-air cinema in Natal. The second was the reference to writing ‘The Growth of a Unit’ and the third was to David Stirling’s masterly command of a useful leadership technique. But the fourth is poignant, because it alludes to the impact of the war. He had recalled his last St Patrick’s Day in Ireland in 1940, before going overseas. ‘Lot of everything flowed under the bridge since then.’ Not only was there a lot compressed into that statement, there is the suggestion of emotional numbing.

But Mayne’s instincts in signing on for the Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey were sound. There would have been time in the vastness and the solitude of Antarctica to think without the social pressures of ordinary living; and writing a fictional account of the reality he had gone through the previous few years could have been therapeutic. That his time in Antarctica was cut short was something that he came to terms with. He may have suspected for some time that there would be a future reckoning for the earlier damage to his spine. But that apart, he knew that when the two-year contract came to an end, decisions about the future would still have had to be made. The shortened time with the survey probably had some benefit as well: like the diver coming up from the pressure at great depth, it provided a period of ‘decompression’ before returning to family and local community.