Introduction

The central purpose of this book is to feature family and house ghosts, thus to have in print numerous narrative accounts that people feel reflect virtually two centuries of fact and fancy concerning themselves and their progenitors. These accounts that focus on the supernatural also describe an abundance of folk values that tend to make them precious in the eyes of the tellers and those persons who sit spellbound while hearing the stories being recounted.

Kentucky has a rich legacy of ghostly visitations, especially descriptive accounts associated with old houses and deceased family members. These orally transmitted stories are rich in historical detail about these houses and related buildings, and also provide details relevant to people’s assumed-to-be-true encounters with the supernatural. Some of the stories herein go back to pioneer times, and certain others are tied to antebellum homes and family progenitors who were present during those early years. Some even reflect the bitterness of slavery conditions and fratricidal conflict during the Civil War. All in all, ghost stories contain a lot of historical information in that they accurately describe folk practices and beliefs that have long been forgotten except by the older residents. It is important to record and place these stories in print so that the historical and personal information contained in them will be preserved for future generations.

The early generations notwithstanding, most of the interesting accounts in this book portray life and times of recent twentieth-century generations. Whether traditional or personal, such stories are an integral part of Kentucky’s regional identity with the South, and they especially enhance social and cultural ties with family, community, county, and state. From the mountains in the Appalachian portion of the commonwealth, across the lush pasturelands of the Bluegrass region, the hill country of both north-central and south-central Kentucky, and the flat-to-rolling terrain of western Kentucky, no part of the state is exempt. The force of these supernatural stories is strengthened by their obvious intent to portray things as they really happened, not merely to amuse the listeners. In this regard, Kentucky is much like other Southern states. Author Kathryn Tucker Windham writes, “There is something about the South that encourages, perhaps even requires, the presence of ghosts and the measured retelling of their deeds. And, somehow, these stories provide a nostalgic link with the past, with generations who were here before.”1

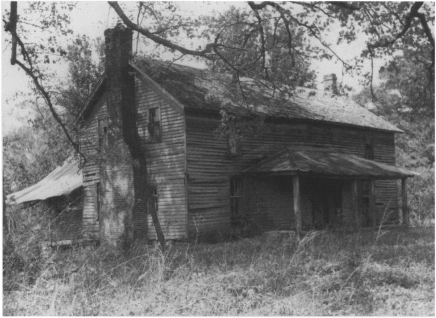

Old deserted houses like this one in the eastern Pennyroyal section of the Commonwealth are frequently the locations of family and community stories about ghostly entities. (Photo by the author)

Virtually all residents of Kentucky have shared, and many still do, in storytelling events involving supernatural visitations. Throughout history, Kentuckians have cultivated and perpetuated the telling of traditional oral narratives. John Johnson, resident of Carter County during the 1930s when he was already in his eighties, offered the following commentary to Milford Jones, member of the Federal Writers Project, about family storytelling situations:

In my growing up or younger days, the fathers, mothers, and older people would sit around the fire of a night at home and tell all kinds of scary stories about things they had seen and heard. These stories kept us children wondering and scared all the time. We were always expecting some great disaster to happen to us, such as the devil or some hideous being would carry us off. These tales and stories made me afraid to be out of a night. When I was a boy, if I had to pass a graveyard or an old deserted house, I was always looking for something fearful, or to be carried off.

The mothers would sing scary songs or tell the children ghostly tales in order to make them mind.2

As indicated in the foregoing statement, whether true or not true, these stories may serve as subtle warnings especially to children and, on occasion, to elderly persons as well. For example, after a haunted-house story is told to describe a headless being that roams from room to room with an axe in hand, a parent or grandparent may say to a child, “Stay away from that old house. Old Man Evans thought he would be killed when he saw that thing, and it just might happen to you.” Whether or not the house is haunted, stories such as this may provide sound advice to the child to stay away from that old place so as not to be snakebitten, attacked by animals, or encounter various other dangers associated with the house. In earlier times, children thus understood the situation and were typically frightened into submission.

Peoples beliefs and stories about death and dying, and the return of the deceased as ghosts, tell a lot about who these people are, where they came from, how they deal with religious and traditional beliefs, and how they cope with bewildering facets in their everyday lives. Viewed in this social context, stories about supernatural entities are not merely fictional accounts that people dream up. Instead, they are accounts based on personal experience, trust, and tradition.

Supernatural tales thus describe extraordinary events typically believed by the storyteller to have really happened. People like to hear these accounts because they are told to as “actual experiences of the contributors or of their relatives or friends. In almost every case the original teller, at least, believes that he or the person involved has had a supernatural experience.”3And these accounts are usually told to the listener in such a way that the recipient person often feels as if he or she is viewed as a very understanding individual who is being provided with very private, personal information. These accounts of spirit visitations grip the listeners, and especially the tellers, with a genuinely uncanny power. Most of these gripping, spooky stories are believed from the heart, even when logical rationale would assert that what is being described really did not happen. Although encounters with these spirit-like creatures are generally dismissed by hard science, people from all walks of life and in all world cultures nonetheless cling tenaciously to their beliefs in the return of deceased family and community members as spirits. Thus it is that the stories told to describe what happened typically gain a power of felt veracity.

Nelson Maynard II, current resident of Louisville, had the following to say about his belief in supernatural entities during his growing-up years in Pike County:

I can’t tell you exactly why I am so interested in ghostlore, or in the field of folklore in general, but for as long as I can remember I have had an interest in old-timey ways and traditions, and a particular fascination for ghost tales. Clearly, my grandparents grew up in much more interesting times, what with their log cabins and spring houses located on the old countryside….

The notion of earthbound spirits hovering about in the fog and shadows fascinated me. Growing up on Johns Creek, I was absolutely certain our old house and the countryside was positively bursting at the seams with ghosts. … As a lad, I would sometimes wake up during the night scared, then go across the hallway to my parents’ room, but taking care to first pull the sheet from my bed and put it over me so that the ghosts would think I was one of them as I walked down the hall.

This eventually developed into a bit of good preschool dread for me, as my folks endeavored to convince me that there were no such things as ghosts. They were only make-believe and perfectly harmless. Ghost stories were only stories after all. So, I eventually lost my dread of ghostly encounters, but not my fascination for them.4

According to folklorist Barbara Walker, “If the supernatural is seriously considered, the events and phenomena reported or described within a group give us evidence of a particular way of perceiving the world. It provides insights into cultural identity…. How groups regard the supernatural contributes to thought and behavior, and by attending to those patterns, we gather a fuller understanding of what is meaningful to the group, what gives it cohesion and animation, and thus we develop a rounder perspective of cultural nuance, both within the group and cross-culturally.”5

No amount of formal historical documentation can provide the human understanding relative to beliefs, customs, worldview, and social values as that which is available in oral traditional stories. And while the supernatural visitations described in this book do not offer a total picture of Kentucky’s people, simply reading these accounts helps to provide the reader with central ideas and values that continue to undergird daily life in Kentucky and depict local life and culture in meaningful terms. These oral stories are especially valuable in that they reflect people’s inner lives by articulating their beliefs, fears, dreams, and hopes.

Many people think of supernatural entities as being something terrible, something that is here to scare you, to get revenge, or perhaps even to kill you. On the other hand, those persons who witness spirit visitations from deceased family members such as a grandparent, parent, spouse, or child, often find their presence comforting or informative. Stories that recount the return of a family member as a spirit entity to the land of the living portray the visitations as necessary, so as to warn, console, inform, guard, shield, reward, or save the life of a living relative.

A Bowling Green woman shared with the author approximately twelve years ago how her grandfather’s spirit saved her life the previous week. In explaining what took place, she stated that she left Bowling Green the previous Wednesday at 2:00 p.m. en route to Louisville. She was alone in the automobile. About the time she got within fifty miles of her destination, she could feel herself falling asleep at the wheel, something she had never done before. Apparently, she did fall asleep. At that precise time, someone’s hand from the back seat of the car grabbed her by the shoulder and began shaking her to wake her up. She saw that she was headed for the ditch, and simultaneously saw her grandfather sitting there in the back seat. She immediately steered the automobile back onto the interstate highway, then pulled over to the side of the road so as to regain her composure. Once the automobile was in a parked position, she turned around to speak to her grandfather and thank him for saving her life. “But even though I saw him after his hand woke me up, he was not there any longer,” she stated. “But how could he have been? Grandfather has been dead for five years.”

This is one of the many, many accounts that people have shared with the author to illustrate the love, concern, and compassion that dead relatives continue to have for the living. Some even tell of the return of a family member to inform a living relative where his or her money was located—money that had been hidden in the house, in a tree, cave, or buried underground for many years. Thus, family ghosts return for a definite reason. Some house ghosts are also those of family members with no explicit reason for their return.

One tenth of the accounts that deal with the return of family members as ghosts claim that the return was as an unseen presence of a known person. All other stories report that the family ghost was seen and fully recognized by the recipient person. In numerical order of appearance, of the seventy-four family ghost stories herein, mothers made the most frequent visitations: twelve total. Of the other spirit visitors, there were nine grandmothers, eight grandfathers, six husbands, five fathers, four wives, three daughters, three uncles, two brothers, two sisters, two grandsons, two cousins, one great-grandmother, one aunt, and one little baby. In seven instances, the spirit visitations included two or more family members at the same time. Whether seen or not, the ghosts let their presence be known by walking on stairways or in hallways, knocking on doors, wailing and moaning, crying, or simply talking to the living.

While some family ghost stories do not explain why the spirit entity comes back to the earthly realm, most do. Articulated reasons for these returns, as indicated in the stories, include (1) the desire to console family members who are in agony, turmoil, sadness, or failing health; (2) to warn a family member of impending death; (3) to place burden of guilt on parents; (3) to reassure a family member that he or she is still loved by the deceased; (4) to tell a spouse that it is okay to remarry; (5) to agonize a former husband who had mistreated her; (6) to reveal buried treasure; (7) to persuade a brother to stop his rowdy behavior; (8) to return to a favorite piece of furniture frequently occupied when the spirit was a living person in this world; (9) to inform a widow how to conduct her business; (10) to say a final goodbye; (11) to occupy a spot where the death occurred.

Numerous Kentucky communities lay claim to a haunted house and its patron ghost. Haunted, or “hainted,” houses thus comprise the largest topical category of Kentucky ghost stories. No other category comes close. Most haunted houses in Kentucky are “people” houses—houses that were primarily designed and built by local people, for local people, using local building materials. And in times past, a residential structure often remained in the family for three or four generations; some even longer. This explains why so many of the stories about an “old hainted house” are about the return of deceased family members, who dearly loved the old home place during their life span here on earth. Of the 214 stories about house ghosts in this book, approximately one-third of the supernatural entities are not unidentifiable; female ghosts are featured in one-fourth of the stories, the exact same number that portray male visitations. Eleven stories describe the return of two or more family members at the same time as ghosts; eight of the accounts focus on babies, seven deal with children of various ages, and five feature animal ghosts.

The stories in the haunted-houses section help the reader discern the nature of ghostly appearances. In terms of numerical frequency, eighty-five percent of these stories focus on ghostly noises—sounds that especially include footsteps, ghastly cries and screams, rattling dishes, closing of doors and windows, hammering sounds, tinkling bells, chairs rocking back and forth, activated sewing machines, musical sounds emanating from various instruments such as pianos and fiddles, and hymn singing.

The next largest category of ghostly manifestations in the haunted-houses section features ghostly entities that are usually associated with the above noises. They are seen by the recipient persons, but there is no said-to-be direct contact with the ghost. Forty-two percent of these returnees are the ghosts of deceased family members; others include headless beings; some represent spirits that return to eke out vengeance against those who did them wrong in their living years; others are spirits of individuals who simply loved the old home place and cannot move out, even after death removed them from their wonderful earthly abode. Often, ghostly entities are seen as hazy, misty figures and shadows, some of whom are former plantation slaves who were cruelly mistreated by their owners. Even animals, such as dogs, sheep, and wildcats occasionally appear as ghostly creatures. No matter how or what was experienced in these haunted houses, numerous families moved out and away from them. They couldn’t take it any longer.

Other ways in which ghosts make themselves apparent to the living is by appearing as a felt presence or as a pair of ghostly eyes; sending out cold or chilly breezes; turning electric lights and electrical devices off and on; moving pieces of furniture and miscellaneous house furnishings from place to place; opening and closing windows and doors, even in the presence of living witnesses. In one instance, a ghost appeared as a puddle of water on the floor.

In the house-ghost category, it is of interest to observe where the ghosts appeared and in what numerical order. The bedroom is the most common place where ghosts were heard, felt, and sometimes seen. Ghostly visitations throughout the house ranks second. The stairway alone is next, followed by the upstairs area in general, the parlor or living room, the hallway, basement or cellar, kitchen, attic, dining room, porch, and the roof.

The manners in which the ghosts made persons aware that they were present included, in order of numerical instances, ghostly noises of many varieties; identifiable ghostly presences seen by viewers; lights, shadows, and misty figures; felt presences; ghostly touches felt by the living; scents of various perfumes; and chilly breezes blowing across the room when all windows and doors were closed.

Regardless as to how, when, and in what form these ghostly visitations occurred, those persons who experienced or witnessed the uncanny manifestations will declare that what they saw, heard, or felt really did happen. As a matter of fact, approximately one-fourth of the house-ghost stories were told as personal experiences by the narrators.

The titles of these stories were, for the most part, assigned by the author after analytically screening a story s contents. Seldom do storytellers verbally provide a title for the story they are about to tell. They simply begin with introductions such as “Now, let me tell you a story about a real ghost. Here’s what happened….” Or, if the account is universally told, and the narrators are aware of this, they may begin with wording such as “Let me tell the story as I know it about the face in the window.”

These narrative accounts are printed here verbatim from four main kinds of sources: those spoken into a tape recorder; those taken down on notepads in shorthand version and then reworded as closely as possible to the way they were originally told; those written and submitted by the narrators, some of them by email; and those that appeared as newspaper accounts I sought to retain the original form of the story; thus I never changed the wording so as to falsify the story or change the story’s intended message to the listener. Most of these stories fit the first category—stories that were recorded as told many years ago—and category three, as many were submitted in handwritten or typewritten format.

It will be of interest to see whether these accounts will be passed along from generation to generation as customarily done during ancestral times. Thankfully, some of the stories herein were told by teenagers. Perhaps this signifies that these stories will be passed along to their children and subsequent generations. So let’s read and share these narrative accounts with no feeling of ignorance, superstition, or disrespect toward those persons who provided these wonderful stories. And as you read them, do not forget to identify and glean the historically descriptive bits of information about people and houses, as such information is not likely to be available in any other source, published or otherwise.

Notes to Introduction

1. Kathryn Tucker Windham, Jeffrey Introduces 13 More Southern Ghosts (Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press, 1971), p. 5.

2. Kentucky materials gathered by members of the Federal Writers Project are on file at the State Library and Archives, Frankfort.

3. Ruth Ann Musick, Coffin Hollow and Other Ghost Tales (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1977), p. 4.

4. Nelson Maynard II, Louisville, November 20,2000.

5. Barbara Walker, Out of the Ordinary: Folklore and the Supernatural (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1995), p. 4.