The two categories we are dealing with in this chapter are much less intertwined than liberty and equality in the previous chapter. Justice is usually seen as the queen (Iustitia in Latin) of normative political philosophy and is not expected to have a good neighbouring relationship with solidarity. Solidarity may stand up as a critic, if not an opponent, of justice: the ‘and’ between the two terms is sometimes replaced with ‘vs.’ In mainstream textbooks of political philosophy, solidarity has no business, whereas justice reigns like emperor Charles V (1500–1558) of the Holy Roman Empire, on whose lands, which included the bi-continental Spanish Empire, ‘the sun never set’.1

The centrality of justice is partly due to its position as a meta-category. We can speak of liberty, equality and solidarity in descriptive terms by saying that a country has the highest degree of freedom, a society has a low degree of equality, or the population of a town shows a remarkable degree of internal solidarity. This leaves open to choice and debate whether or not we appreciate freedom in full measure or think it should be subjected to conditions, or believe that a higher level of equality would compromise the economic efficiency of a country. On the contrary, if we say that a society or regime or institution is just, we cannot but issue an axiological statement that is attributing a certain moral or political value to it according to our value system. Moreover, the axiological charge of statements of justice easily translates into prescription: what is recognised as just, must be enacted by agents. The predicate just/unjust can never be descriptive, as it is, by its nature, evaluative. What we, according to our particular value system, recognise as just or unjust remains to be seen: for racists it is just to exclude people with another skin colour from societal life and government; for other people this is utterly unjust and despicable. Justice is not by itself a magic word that guarantees universal respect and recognition.

In §1 a grid of possible meanings of justice is offered, while in §2 we look into the most popular example of distributive justice together with its most refined theorist, John Rawls, as well as some of his critics. What solidarity means and why it is worth being taken seriously is explained in §3.

In the history of Western political philosophy, justice started her brilliant career in Plato’s Republic, in which δικαιοσύνη/dikaiosune2 is argued by Socrates not to be ‘what is useful to the strongest’ (Plato BCE 380, Book 2, 338c), as the Sophist Trasimachos in his scepticism or nihilism would have had it, but rather to consist of ‘giving to each what is owed to him’. This very same principle ‘unicuique suum tribuere’ will be crucial in Roman law, in particular as highlighted by the jurist Ulpian (AD 170–228), along with the other principle ‘naeminem laedere’/do not inflict harm on anyone. Starting with Plato, s/he who raises the question of justice looks at the existing power structure with critical eyes and asks it to justify itself with regard to criteria that are neither self-centred nor utilitarian or opportunistic – yet modern utilitarianism is itself a theory of justice having the wellbeing of the greatest possible numbers of persons as target. Questioning power in the name of justice (but also liberty or equality or solidarity) means putting its legitimacy to the test, as we anticipated in Chapter 2, though we cannot here unfold in its entirety the connection between political legitimacy and normative categories.

Now, a first criterion useful to put order to the many versions of justice is to distinguish substantive from procedural versions. The former understand justice as the conformity of our acts, laws, political regimes to substantive values such as equality in one of its several meanings or to those enshrined in a cosmic order or belonging to what we regard as natural order – as is the case with natural law theories. In common parlance, particularly in Europe, ‘just’ is often by default merged with ‘equal’ or ‘egalitarian’.

Procedural versions avoid the identification with substantive, hence controversial and evolving values, and strive for a higher degree of generality by seeing justice realised in the application of a rule of behaviour that is applicable to all concrete cases. The drawback with these versions lies in the often empty abstractness and fungibility of some formulas such as unicuique suum, which leaves open which rule (and which value system) should be followed in order to identify what is owed to each. This found a macabre confirmation in the German version of this principle Jedem das Seine being used by the Nazis as a menacing maxim engraved on the iron gate of the Buchenwald death camp.

A different story regards another procedural principle we have already met back in Chapter 7 where we discussed our normative attitude towards global/lethal challenges: the Golden Rule. In the Old Testament this principle is formulated negatively ‘and what you hate, do not do to any one’ (Tobit 4:15); from the Gospels let us choose the positive formulation given in Luke 6:31 ‘and as you wish that men would do to you, do so to them’. The transcultural nature of this rule is proven by its likely origin in India and its presence in Confucianism; its interpretations range between do ut des reciprocity (a favour for a favour, or the other way around: do not excite others to perform tit-for-tat) and universal respect for every person’s dignity. In this second reading, it comes closer to Kant’s categorical imperative in its second formulation, as quoted in the previous chapter (cf. Kant 1785, 36). Let us note that, properly understood, these principles regard relations between individual persons, not communities or polities. It is therefore an unduly simplification to apply them directly to political relationships, except we are determined to deny any autonomy to politics and want it to be – as Kant wanted – an application of moral laws to a field whose nature can however be deemed to be very different from morality.

Let us now look at another classification of justice: commutative/retributive and distributive. The first elements of this distinction were laid down by Aristotle in Book V of Nicomachean Ethics. Commutative justice tells us to burden people (with a fine, or a prison term) in a way proportional to their wrongdoing; or to compensate them for the harm they suffered or the commendable acts they performed in a measure that matches their loss or performance. This type of justice is aimed at regulating the exchange between evils or goods. As such, it does not entail an entire scheme of political cooperation for society, but addresses primarily two cases of such an exchange: civil and criminal justice (tort law and penal law) and the wage system. In the first case we speak of retributive justice if the justice system focuses on the retribution for the wrong done that can be claimed by both victims and the state. It is, however, known that a justice system based only or primarily on retribution fills prisons to the utter limit, as in the USA since the mid 1990s, but is unlikely to lead to a permanent crime reduction; re-education – or rehabilitative justice – as the primary aim of the sentence works better.

As to the wage system, the point rather regards the capitalist system as presumably the cause of an unjust distribution of the goods produced by social cooperation, or exploitation. This used to be, and still is, a widespread feeling, but its classical formulation was given some 150 years ago by Karl Marx (1867) in the first book of Das Kapital, Chapter 4, §3. What appears to be a fair exchange between the wage-labourers offering their labour-power and the capitalist rewarding them with an amount of money corresponding to what the labourers and their family need to survive is only illusion, because, in fact, the capitalist lets the workforce toil for a much longer time and makes a profit out of this. In the sphere of production, in the factory, the illusion of a fair exchange born in the sphere of circulation on the job market vanishes. This classical explanation, meanwhile abandoned by most economists, was presented by Marx as a further development within the labour theory of value initiated by Adam Smith (1723–1790) and David Ricardo (1772–1823). It found an extension in Arghiri Emmanuel’s (1911–2001) theory of the unequal exchange between developed and developing countries in the capitalist world economy. The political outcome of these theories of social and international injustice were revolutionary and anti-imperialistic movements.

Distributive justice regards the rules of how to organise the distribution of material and immaterial goods to actors (persons, classes, countries) seen as members of a group of a given dimension (citizens of a country, countries of the world). Plain examples of the rules are distribution proportional to the personal merits in meritocracy, to the hours worked on the workplace, to everybody’s needs and/or skills in an ideal society. Some of these topics are known to us from our reflections on equality, but now the corresponding models come provisioned explicitly with the predicate ‘just’.

From Plato onwards philosophers have theorised several models of polity based on increasingly elaborate conceptions of justice. The most sophisticated and, at the same time, the most interested in a political model of justice, ‘the first virtue of social institutions’ (Rawls 1999a, 3), remains John Rawls’s theory of justice as developed in 1971 (now Rawls 1999a, 1993 and 1999b). The purpose of Rawls’s research is how to ideally set up a polity or ‘well-ordered society’ whose institutions are based on justice as fairness; he understands this model of a constitutional democracy to be an alternative to utilitarianism, which is, in his view, unfit to secure the basis of such a regime because it gives the ‘calculus of social interests’ (Rawls 1999a, 4) priority over the liberties of equal citizenship. While rerunning the basics of the contractarian tradition, from Locke to Rousseau and most importantly to Kant, Rawls designs an ‘original position’ in which citizens find out what the best principles of a just society are expected to look like. In doing so, their impartiality is assured by a ‘veil of ignorance’ that prevents them from knowing their social status, their possession of natural assets and abilities, the conception of the good they may adhere to, the generation of which they are a part (Rawls 1999a, 118–123). They are thus enabled to determine the best principles of society removed from particular interests and ideologies they would otherwise tend to let prevail. The outcome consists of the principle of greatest equal liberty for all and of a second principle, called the difference principle; they are both developments of a more general conception of justice:

All social values – liberty and opportunity, income and wealth, and the social bases of self respect – are to be distributed equally unless an unequal distribution of any, or all, of these values is to everybody’s advantage.

(Rawls 1999a, 54)

The difference principle is contained in the qualification ‘unless …’ and is further specified in §46 of A Theory of Justice in the sense that social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they ‘are to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged’ (Rawls 1999a, 266). This can, for example, justify fiscal policies that redistribute income in favour of the less advantaged layers of society, but also a rejection of radical egalitarianism, which would cancel the stimuli given to the efficiency of national economy by individual aspirations to higher income, to be attained by business creation and higher productivity. In Rawls’s order of priority, efficiency ranks, in any case, after equal liberty and welfare. The priority given to a ‘system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all’ (from the First principle as formulated in §46) explains why Rawls’s conception has been seen as the peak of (left-leaning) liberalism in the American sense of the word. In Political Liberalism (1993) Rawls corrected his own previous view of justice based on liberalism as a ‘comprehensive doctrine’ (including a theory of moral values and metaphysics) and focused on the political character of democratic liberalism. This stance is deemed to facilitate reaching an ‘overlapping consensus’ (another key item in Rawls’s vocabulary) among different conceptions of justice, provided the debate is regulated by ‘public reason’, which acknowledges only rules that can be justified in front of those to whom the rules apply; for example, civic rules deriving from a particular religion are not of this sort, since among the citizens to whom they are expected to apply some or many are no believers and are not ready to accept religious justifications of those rules.

Of the innumerable debates ignited by Rawls’s philosophy since 1971 I shall name only a few here: first the dissent about international justice that unfolded within his own followers; then, in the last part of the section, follows a brief account of the critique launched by what we could dub the opposition (Nozick’s libertarianism, communitarianism, Derrida). Only later on we will deal with the existential question as to how far general normative theory or ‘ideal theory’ makes sense in political philosophy.

Rawls conceives of international society as a society of peoples (scil. countries), not free and equal individuals; remaining far away of any cosmopolitan egalitarianism, he sees for wealthier countries only a duty of ‘assistance’ to ‘burdened’ societies, helping them attain decent and stable domestic institutions that respect human rights; this does not include a duty to narrow the gap between rich and poor. This is, with various arguments, criticised by cosmopolitan theorists of justice such as Charles Beitz (2000) and Thomas Pogge (2001), and this discussion has given birth to a current of studies and suggestions called ‘global justice’ that issues and assesses policy proposals concerning problems such as poverty, the reduction of illiteracy, the promotion of gender equality, a better food production and distribution, but also issues of international criminal justice, particularly after the creation of the International Criminal Court. Contrary to this tendency, David Miller (2000) has argued that, as nation states are ethical communities, we owe to our fellow-nationals duties that are not only different from, but also more extensive than, the duties we owe to human beings as such.

My thoughts in Chapter 7 on how to treat with respect and fairness the people of the far future may seem to come closer to this current, except that they differ from ‘global justice’ for two reasons: first, my proposal results from a political philosophy of man-made lethal challenges, not from elaborating on general normative principles. Second, the time universalism I propose finds correspondence neither in Rawls’s principle of the ‘just savings’ for future generations nor in the global justice literature, focused as it is almost exclusively on space universalism. A further difference lies in the political (as different from moral) reflection that reducing inequality and promoting retributive justice for human rights violations worldwide is not only a normative issue of justice, but also an issue of stability and peace. Egalitarian steps, for example, allowing more and more immigration from less wealthy countries because all human beings have a right to what Rawls dubs primary goods, cannot be undertaken simply out of their rightness, but must find the consent of the hosting populations, which cannot be expected to flow from discourses of charity or justice, but as the result of a well-designed political process, in which the interests of both guests and hosts are both taken into consideration. Large-scale and efficient development aid delivered in the emigration countries (side-stepping if necessary their rogue regimes) can prevent mass emigration, which is unavoidably tied to human suffering. In any case, the category of solidarity fits these problems better than that of justice, as we shall see.

***

Opposition to Rawls’s theory of justice came up vigorously three years after its publication with Nozick’s minarchism or theory of the minimal state (Nozick 1974), in which freedom, rather than distributive justice, is the leading principle and ‘end-state theories’, so-called because the final distribution is normatively fixed once and for all, are rejected. Nozick favours a historical theory of distribution, which respects property as it was originally distributed or later acquired, though a rectification procedure for past injustices is also foreseen. In his utopia people who disagree with the state of affairs in their own society can leave and found another one. In this extreme case of ideal theory (see below), the relationship between liberty and equality is brought back to the radical opposition that marked the original tension between liberalism and democracy.

A more systemic and less otherworldly opposition to the theory of justice and liberalism altogether is represented by communitarianism, a wide field including philosophers of quite diverse orientation such as: Alisdair MacIntyre (1981), Michael Sandel (1982),3 Charles Taylor (1989), Michael Walzer (1983). The landscape here is totally different: not the isolated, atomized, unencumbered individuals of liberalism, who in this communitarian description are all driven by self-interest, but the community with its traditions and customs. In it alone can individuals achieve a sense of their associate existence in a mindset that is guided by the search for meaningful ends rather than the enacting of abstract rights. The good is more important and a better motivating force than the right, as the communitarians believe in a shift backwards from a deontological to a teleological posture.4

In the communitarian rejection of liberal individualism themes come up which were all anticipated in Hegel’s critique of Kant’s moral philosophy; this was sort of inevitable, since Rawls himself presents his theory as a rerunning of Kant undertaken after (and against) the utilitarian wave that went through (Anglo-American) thought in the last two centuries. Kant reborn could not but evoke a renewed Hegelian wave, though communitarians lack Hegel’s view on world history. They do rather echo the anti-liberal and anti-capitalist, in a word anti-modern, stance of Romanticism and recall to mind the conception of community/Gemeinschaft examined in Chapter 4. Though not without influence on the philosophical debate in Europe, communitarianism has been almost exclusively an American phenomenon, and the ‘community’ it intends can only be fully understood by keeping in mind American social history and the particular aura this word is surrounded with in American political and religious language.

A critical comment on the liberal notion of justice has been formulated in France by Jacques Derrida (1930–2004), the philosopher of the now popular deconstructionism. He has pointed out the amount of force and willful decision that lies at the origin of whatever system of justice, which must therefore remain self-contradictory and impossible; his philosophy of democracy is, rather, centred on the notion of hospitality, along with the tension between the unconditional and the conditional versions of it.

We are now turning to a category that enjoys little recognition in political philosophy and is subject to misunderstanding, partly because of its binary status, analytical and normative. Its analytical version is best known through the work of Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), who along with Max Weber is regarded as the (French) founder of sociology. For him, solidarity is the force that keeps human beings together in society and consists of two sub-types corresponding to different structures of society. In traditional societies, mechanical solidarity prevails, often enforced by punitive law and violence, among individuals that are very similar to each other and live in communities with a low degree of integration, but strong common values. Organic solidarity develops in modern society, in which the division of labour creates differentiation and interdependency among individuals.

Durkheim’s solidarity concept remains objectivistic, inasmuch as it focuses upon the driving forces, resulting from the evolutionary stage of society, that keep it together; while we are rather interested in solidarity as a piece of the subjective side of politics (solidarity felt as such is a layer of political identity). We are better served by the definition found in the Oxford Dictionaries:5

Unity or agreement of feeling or action, especially among individuals with a common interest; mutual support within a group.

This wording rightly moves the focus to a ‘feeling’, though in the philosophical language we cannot say solidarity to be just an emotion. Also, this definition expresses a phenomenology of solidarity, but makes no hint at its normative element: the solidarity we are talking about here, taking place in an ‘organic’ Durkheimian context, brings together feelings and a sense of obligation, though this obligation does not result from a higher principle, but is rather felt and enlivened as a known condition of the group’s (in our case, the polity’s) survival, while the individual can only find in group support and meaning for one’s own life. This explains my suggestion to understand solidarity as a self-imposed obligation to and a feeling of mutual support and sympathy between equals. Self-imposed out of the knowledge that without mutual support of its members the polity is likely to dissolve, while none of the other normative categories can nourish the cohesion it needs to survive and perhaps flourish – cohesion is necessary also in order to let liberty, equality and justice develop. Sympathy, which is here introduced without a chance to discuss its relationship to David Hume’s (1711–1776) conception of it, is the moral sentiment accompanying the readiness to mutual support, and means the ability to put oneself in somebody’s else shoes, sharing imaginatively her/his pains and problems.

‘Between equals’ requires a more differentiated explanation. The equality meant here is not matter-of-fact, but normative: I lend my support to others because I recognise them as equal in rights and dignity with myself, even if they are presently unequal in the enjoyment of freedom and life chances. This is what distinguishes solidarity, which is horizontal, from charity and philanthropy, which rather evoke verticality. Also, solidarity as the fundamental category we are talking about cannot be downsized to its meanings in social aid groups or in Catholic social thought. Lastly and consequently, solidarity is seen here as a political virtue to be implemented by the state, not merely as a relationship between individuals.

Another question regards how to determine the perimeter of the equals: equal in the local community, in the region or province, in the nation, in a civilisation, or among humankind? To date, the current definitions of solidarity have pointed at the (however defined) particular group as the sphere within which solidarity can sensibly be expected to develop. This is well-known from its social history in the West: the Freemasons in the Enlightenment, the clubs of the French revolutionaries (before they started to send each other to the guillotine), the movements and later the parties of the working class, including their pledge to the international solidarity of the proletarians, who, however, could not but massacre each other in the trenches of the Great War. Yet can there be, contrary to this factual limitation, a solidarity extended to the whole of humankind, as it has been suggested over time by humanists, pacifists and religious leaders? With an eye towards religious cleavages and the upsurge of nations, this suggestion or appeal was, with good reason, regarded as politically ineffective. Things are now changing, as we have learned in Chapter 7: with respect to its chances to survive global and lethal threats, and only in this respect, humankind is becoming the dimension in which men and women can experience solidarity with each other and the fellow humans of future generations.6 This has normative relevance, but also – as explained above – an analytical profile: without assuming that an initial form of the solidarity of humankind is at work, especially with regard to future humanity, it is difficult to explain the progress made, for example, by a more reasonable climate policy at both a national and international level. Self-interest or security considerations do not explain everything that is going on in politics, as we shall see in the Epilogue.

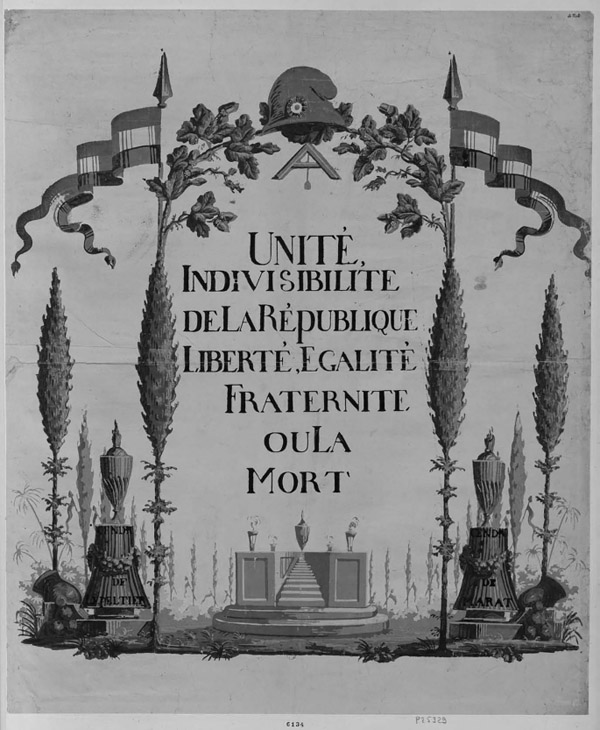

The relevance I am giving to solidarity comes from, among other things, the puzzlement about the disappearance of its predecessor fraternité from the glorious triad ‘liberté égalité fraternité’ of the ‘ideas of ’89’ (scil. 1789) – the brilliant career of the two first partners notwithstanding. It looks like solidarity had been dismissed or pushed to the sidelines due to three adverse and illusionary beliefs:

The disruptive effects of the market (A) on the social fabric when it is not shaped by rules chosen by political decision have showed up time and again in early and then again in postwar capitalism. The 2008 financial crisis was the definitive proof of unchained neoliberalism’s failure in making the economy work to the general benefit and to preserve the society in good health, instead of preaching a limitless possessive individualism. The consequences for political cohesion, such as populism and the perversion of direct democracy have been also described above in Chapter 5. Justice theory (B) does not seem to be on its way to influencing politics as the ‘ideas of ’89’ once did and remains an academic business (more on ideal theory in the next chapter). The cohesion furnished by nations (C) and their degeneration into nationalism has largely vanished after 1945, all attempts (post-Soviet and post-Yugoslavia politics in the 1990s, Euroscepticism paired with national pride in EU-member states, Arab nationalism) to reinstate it could not but fail and have sometimes shown poisonous side effects.

It is against this backdrop that solidarity needs to be rethought as both a normative category (from which duties of solidarity derive for policy-making actors) and a sense of belonging together that survives any defensive closing of the borders, both geographic and mental. Since solidarity is a word coming up more and more with regard to migrants, it is perhaps useful to be explicit on this matter: solidarity does not mean admitting all migrants for whatever reason they migrate from all possible corners, but taking care of them wherever they are, instead of leaving them in the hands of traffickers or violent governments. On the other hand, reinstating solidarity as a self-imposed obligation is not a normative indication that can go without a measure of political wisdom, for at least two reasons. First, solidaristic or welfare policies – if not well-carved and provisioned with safety mechanisms – can be easily misused by people who end up using them as a permanent instead of a temporary source of outcome, and acting as a lobby of welfare receivers. Second, the difficulties of states overburdened by tasks and not receiving enough tax money are likely to last for an entire epoch until a new wave of (sustainable) growth takes effect or the economy is reformed in a more efficient and more just way – a model for this combination is, however, not in sight.

In the light of these two considerations, a problem that comes up again is our stance towards future generations, this time however not in the framework of lethal problems affecting people of the far future. Though support cannot be mutual between generations if their life-spans do not partially overlap,7 here too time universalism applies: there is no reason why future generations should not deserve our solidarity like our contemporaries, particularly with reference to public debt and the pension system. Also, generous solidarity towards contemporaries is wrong if it compromises or spoils in advance the financial premises of similar policies to be implemented in 50 or 75 years. Let us also remark that in countries with declining birth rate, two aspects of solidarity policies – the acceptance and integration of migrants and the care for future generations – converge; the first can reveal itself to be instrumental in keeping the social security system afloat to the benefit of the posterity.

Finally, my reintroduction of solidarity as a self-standing category in the family of normative concepts accompanying politics is due to the intention to complement this family with a neglected member, by no means to counterpose it to the other, more celebrated partners. Rather than rejecting liberal political thinking altogether, as communitarians do, solidarity as a category in the company of the three others appears to be able to give answers to the questions liberalism leaves open with regard to social and political cohesion as well as the interconnectedness of individuals, who remain the fundamental agents.

How liberty and equality, justice and solidarity can interplay is not up to a textbook to determine, but is rather left to citizens, polities and thinkers reflecting and acting within specific configurations of problems and conditions. The tools that may be useful to them have been presented in the last two chapters, while in the next one suggestions and warnings as to how to use those tools will follow.

1Titles of books and articles are nowadays flooded with ‘justice’, added as a sort of universal operator (as they say in logic) to the most various topics, both in general and applied political philosophy of normative obedience. In Cerutti (2016) this approach is criticised with specific reference to climate ethics as the wrong way to develop a political philosophy of climate change.

2This word means both ‘justice’ and ‘righteousness’. As with other words relevant to political philosophy, the semantic of justice is not homogeneous across languages.

3Sandel is also the author of the famous online course (MOOC) Justice, available on the Harvard-MIT edx.platform at http://www.justiceharvard.org/.

4For this terminology see the next chapter, §1.

5 www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/solidarity

6With regard to them, I have used in Chapter 7 the notion of empathy, which is related to sympathy, though being by no means its namesake.

7This is true for support, but not in the same measure for sympathy: if we cannot know if our posterity will look back upon us with sympathy, we can, nonetheless, act in a way that we can reasonably expect it will induce them to do so.

Aristotle, Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια/Nicomachean Ethics, e-book available at http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.html

Beitz, Charles (2000) Rawls’s Law of Peoples, in ‘Ethics’, July, 669–696.

Cerutti, Furio (2016) Climate Ethics and the Failures of ‘Normative Political Philosophy’, in ‘Philosophy and Social Criticism’, 42(7), 707–726.

The English Standard Version Bible, e-book available at: http://biblehub.com

Kant, Immanuel (1785) Grundlegung der Metaphysik der Sitten/Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, Cambridge: Hackett, 1993.

MacIntyre, Alasdair (1981) After Virtue, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Marx, Karl (1867) Das Kapital/Capital, Book I, e-book available at www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/epub/

Miller, David (2000) Citizenship and National Identity, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Nozick, Robert (1974) Anarchy, State, and Utopia, New York: Basic Books.

The Oxford Dictionaries, available at www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/

Plato (380 BCE) Πολιτεία/The Republic, Book 2, available at http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.3.ii.html

Pogge, Thomas (2001) Priorities of Global Justice, in Global Justice, Oxford: Blackwell, 6–23.

Rawls, John (1993) Political Liberalism, New York: Columbia University Press.

Rawls, John (1999a) A Theory of Justice, revised edition, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, John (1999b) The Law of People, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sandel, Michael (1982) Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, Charles (1989) Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity, New York: Harvard University Press.

Walzer, Michael (1983) Spheres of Justice, New York: Basic Books.

Reading Rawls:

Freeman, Samuel (2002) The Cambridge Companion to Rawls, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mandle, John and David A. Reidy, eds. (2014) A Companion to Rawls, Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Materials on solidarity:

Bayertz, Kurt, ed. (1999) Solidarity, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Boyd, Scott and Mary Ann Walter (2014) Cultural Difference and Social Solidarity: Solidarities and Social Function, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.