By the time Celeste and Stevie joined us, I’d picked up one of the fliers somebody had already dropped on the ground.

ACCORDING TO THE FIRST AMENDMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION, IT’S AGAINST THE LAW TO FORCE RELIGION ON ANYONE. STAND UP FOR YOUR RIGHTS!

“They are NOT serious,” Celeste said, reading the flier over my shoulder.

“They look pretty serious to me,” Trent said. He pointed to a trio of boys—all of them jocks—who were hooking up a portable loudspeaker to a microphone.

“This is unreal,” Stevie said.

I looked at the crowd of kids that was swelling by the second. Several of them were calling out, “Sweet!” and, “That’s what I’m talkin’ about!” When I peered more closely, I caught a glimpse of someone standing behind them. A guy with a saddened expression—and a ponytail.

A gasp slipped from me.

“Yeah—exactly,” Stevie said.

But she was nodding toward the microphone where Gigi was climbing up onto a box amid catcalls, which she was apparently enjoying.

“Somebody please tell me she isn’t going to make a speech,” Celeste said.

I jerked back to the crowd and tried to find Ponytail Boy again, but he was gone—if he had ever really been there at all.

“Just so you know,” Gigi was saying—too loudly—into the microphone. There was a feedback screech, and about six guys leaped to correct the problem.

“Get over it,” Joy Beth muttered.

“We want this to be a peaceful demonstration,” Gigi went on. “We simply wish to be heard above the preaching that’s been going on at ’Nama Beach High, which is absolutely unconstitutional.”

“What?” Celeste said. Her voice outdid the PA system by several decibels.

“Shut UP, Celeste,” Trent said through his teeth.

“When SHE does,” Celeste hissed through hers.

“My biggest concern—” Gigi was saying.

“Is that you might break a nail,” Stevie said close to my ear.

“—is that there are teachers involved in undermining the constitution.”

“Teachers?” I whispered.

Joy Beth jerked her chin toward a sign carried by that Jeremy kid from history class:

MRS. ISAACSEN SHOULD READ HER CONSTITUTION!

He was holding it up like it was suddenly his mission in life. But from the way he was leering at Allison as she walked beside him with her hand in his back pocket, it was obvious that his true mission had nothing to do with the First Amendment.

“Now that is just WRONG!”

A ripple went through the crowd, and everybody’s neck craned to see who was about to make this little demonstration more interesting. I’d croaked it—out loud—almost before I thought it. And that wasn’t all of it.

“Mrs. Isaacsen never tried to push anything down our throats!” I said. “She’s a great Christian, but she’s not going around selling it!”

“I said I wanted this to be a peaceful demonstration,” Gigi said. Her voice was a study in righteous disappointment.

“So we’re supposed to stand here and swallow a bunch of bunk?” Celeste shouted at her.

“NO!” Joy Beth hollered. She raised a fist in the air. Then she grabbed poor Trent’s hand and held it up with hers.

What went down after that resembled a practiced drill, as though the administrators had been preparing for just such an occasion. Mr. Stennis, the vice principal for discipline, took the microphone from Gigi—with an apology—and told the crowd to go on to class.

Mrs. Vaughn, the academic vice principal, put her arm around Gigi—as though this incident would surely cause an emotional breakdown—and helped her down from the box as about 13 boys crowded around to offer their support as well.

Then suddenly Mrs. Underwood towered behind us. She put one man-sized hand on my back, the other on Celeste’s, and said, “Let’s go, ladies.” The jerk of the cement hairdo included Joy Beth and Trent.

She pushed us through the crowd—who were all either staring as if we were naked or taking shots like, “Busted!” and, “Hey, thanks a lot.” Even when Jeremy said, “Jesus freaks,” Mrs. Underwood acted like she didn’t hear him.

When we got inside the building, she steered us toward the main office. Stevie was on our heels.

“Wait out here,” Mrs. Underwood said to us. “Stephanie, go on to class. You do NOT need to be involved in this.”

But Stevie shook her head.

“We’re all in it together,” she said. “I want to go in.”

“In,” it was apparent by now, was going to be the office of Mr. Wylie, the principal. With so many vice principals on staff nobody went to HIS office unless they were about to be made a Rhodes Scholar or expelled from school. I was pretty sure this wasn’t about a scholarship, and my mouth turned to fiberglass.

The only other BFF who even looked concerned was Trent. His little mouth was pulled in so far, I was afraid he was going to swallow his lips. Celeste, on the other hand, looked like she was ready to take out the next person who crossed her, although she would have to stand in line behind Joy Beth. Even Stevie had her shoulders squared and was the picture of courage. But they were all looking to me. I took in a big ol’ gulp of air and hoped God came with it.

“They can’t suspend us just for expressing our opinions,” I said. My voice had gone back into its frog-like mode. I had no idea how I’d been able to speak so clearly across the schoolyard.

“Did you have to EXPRESS yours like you were trying to incite a riot?” Trent said to Celeste.

“Did you find anything on the Internet, Trent?” I said quickly.

“Now would be a good time for you to start spittin’ out some facts,”

Celeste said.

Mr. Wylie appeared just then and nodded at Mrs. Underwood to usher us all into his office. When he followed us in and shut the door behind him, I was grateful Mrs. Underwood didn’t join us.

Our principal was a short man with a slight build, but he was solid. His white dress shirt fit him well enough to reveal that he obviously worked out on a regular basis. He wore his silver-tipped dark hair in a severe buzz-cut style and had the military posture to match.

He jabbed a finger toward three faux leather loveseats arranged in a U at one end of his office and said, “Have a seat.”

We sank down in unison—all but Celeste, who had to be told twice. Stevie kept a hand on Celeste’s arm after that, which I appreciated. This was SO not the time for Celeste to go ballistic.

God, I prayed—with my eyes open and glued to Mr. Wylie’s grim face—something is so messed up here. Please—give me a word—just a word.

I felt a narrow ribbon of peace slide through me. This was, after all, a chance for us to put the pledge into action. We could handle this like Christians.

“Is there a problem, Mr. Wylie?” I said.

“Ya think?” Celeste said. “They don’t drag you in here to ask how your day’s going.”

I put a hand on Celeste’s other arm. “We’re not going to do that, ” I said to her.

Celeste held a debate with her face for a couple of seconds before she sat back on the couch. “Then you’d better do the talking, Duffy,” she said.

“How about if I do the talking?” Mr. Wylie said. His gaze bore down on me. “I don’t like what happened out there, and I hope you don’t either.”

He didn’t give us a chance to answer.

“Gigi Palmer came to me late yesterday afternoon,” he said, “asking for permission to have a peaceful demonstration regarding some concerns she has about the school. I told her it was fine as long as no one stirred up any trouble.” The gaze drilled deeper into me. He didn’t have to say he thought I’d been out there with a giant wooden spoon. “I also told her that the minute there was any resistance, it would be over.”

He was starting to remind me of a miniature Doberman.

“I wasn’t trying to stir anything up,” I said. “I was just standing up for Mrs. Isaacsen. She’s the best person on the entire staff, and she doesn’t deserve—”

“Mrs. Isaacsen?” he said.

“Kids were carrying signs about her not upholding the constitution,” Stevie said.

“Let’s keep the focus on you people, shall we?” Mr. Wylie folded his arms across his chest like he was Arnold Schwarzenegger. “You certainly have a right to your own beliefs and opinions, but you may not proselytize on this campus.”

“I don’t know what that is,” Celeste said. “But I know I don’t do it.”

“It means trying to make converts,” Trent said. His voice was so faint it was quieter than mine.

“Were we breaking a law out there?” Stevie said.

Joy Beth gave Trent a major jab in the side with her elbow. He slid down, squeaking against the faux leather, but he couldn’t escape Joy Beth’s killer gaze.

“Did you find out some stuff?” Celeste said to him.

Trent nodded miserably.

“Were we breaking the law?” Stevie said again.

“We aren’t in violation of the Federal Equal Access Act,” Trent said through a small hole.

“What’s that?” Stevie was using her softest voice—the one most guys would go into battle for. Too bad Trent wasn’t most guys.

“It means most student-led, noncurriculum-related clubs have to be allowed to organize in public high schools,” he said. “Even religious ones.”

Mr. Wylie recrossed his arms impatiently. “First of all, you weren’t AT a private club meeting—it was a public demonstration. Second of all, I was never informed that there was such a club here at Panama Beach High. And you mentioned Mrs. Isaacsen. A noncurricular club like this can’t be sponsored by a teacher.”

The BFFs all looked at me as if they’d been shot.

“She doesn’t sponsor us!” I said. “And it isn’t really a club. Aren’t we allowed to—”

“Look, people,” he said. “I don’t want any trouble in my school.” He focused his eyes directly on me. “And you, Miss Duffy, have a reputation for finding it.”

“I was the one who got everybody going out there just now,” Celeste said. She flashed a white-toothed smile at Mr. Wylie. “I got a big mouth sometimes.”

“All you need is a little provocation—isn’t that right?” he said. His eyes were still on me. “I don’t want a repeat of this. That’s all. My secretary will give you passes to class.”

Somehow we were shown out of the office and handed yellow admit slips. I was so confused I couldn’t even decide what books to get out of my locker.

“What just happened in there, Duffy?” Stevie said to me.

“I have no idea. We HAVE to talk to Mrs. I.”

I had never needed her more. But when we all showed up at her of-fice for activity period, there was a sign on the door:

NO COUNSELING GROUP TODAY.

MRS. ISAACSEN HAS BEEN CALLED AWAY.

I turned around to locate Michelle, who was filing papers at a nearby cabinet.

“Don’t ask me,” she said. The pitch of her voice was raised several octaves, which meant that was all she was going to say about it.

K.J. flung her bag over her shoulder. It hit her in the back, right where her bandana-print halter top stopped. Mrs. Isaacsen’s “call” must have happened before K.J. got dressed that morning.

“All right, give it up, K.J.,” Celeste said. “What’s this about?”

K.J.’s eyes narrowed to points. “Like I know. But I bet it’s about that demonstration. Her name was all over those signs.”

“I hate this,” Stevie said. She raked a hand through her hair.

“I just hope she doesn’t get fired over it,” K.J. said. “Now THAT would be something worth protesting.”

“We weren’t the ones who started that whole mess,” Celeste said. “That was Gigi’s gig—and it wasn’t about religion. It was about putting Stevie down.”

“Whatever,” K.J. said, and she turned on an almost-stiletto heel and strutted off, thighs exposed.

“Okay, that skirt is out of control,” Stevie said.

But my mind was far from K.J.’s wardrobe. I had a knot in my stomach to match the tangle in my brain. I didn’t even know what to pray for, so for the rest of the day I tried to just let God breathe into me. It was amazing that I didn’t get run over when I was walking to my car in the parking lot after school. As it was I didn’t see Joy Beth until she was beside me, her face set like concrete.

“You okay?” I said. “You aren’t having an insulin reaction, are you?”

She shook her head. Her hair was tucked firmly behind her ears, as if she’d been preparing to lay something on me and she didn’t want anything to get in the way.

“I can’t get in trouble like that again, or Coach Powell said I’d be off the swim team,” she said. She looked at the toe of her Nike as she dragged it back and forth across the asphalt. “I can’t do anything religious on campus.”

“So—I guess baptizing people in the pool is out of the question,” I said.

She didn’t laugh.

“Joy Beth, what’s this about?”

She swung her head in rhythm with her foot. “Coach just says I can’t do anything that’s gonna give the swim team a bad name. Not that we would—but HE thinks so.” For the first time she looked at me, and her eyes were wet. “I have to swim, Duffy. I’ve wanted this all my life, and now I have a chance. I can’t—”

“Of course you can’t,” I said. “I promise I won’t ask you to walk on water or feed the five thousand with your bologna sandwich until AFTER the Olympics.”

She still didn’t laugh. Neither did I.

“You do what you have to do,” I said.

“I think God wants me to swim.”

“Then do it.”

I patted her hefty arm, and she nodded before she walked away, her face aimed toward the pavement again.

What just happened, God? I prayed. I am SO confused.

Which was probably why I found a parchment envelope waiting for me when I went back to my locker before heading home. I didn’t have to open it to know it was from my Secret Admirer. And I didn’t even struggle over who he might be. I’d seen Ponytail Boy that morning at the demonstration. He was back, which meant I really must be in trouble.

What I pulled out of the envelope was not a note but a card—a wedding invitation.

Great, I thought, he’s marrying somebody else.

Stuff from him always made me think weird things.

It was written in his usual perfect handwriting, and it said:

The honor of your presence, Laura Duffy,

is requested at your marriage.

Prepare to meet the bridegroom.

Oneness will be celebrated

with a banquet of praise.

Right about then I’d have taken him up on a marriage offer. Be swept away by a tall, slender man with an ethereal ponytail—or stay here and get clobbered from every side by people who didn’t know prayer from a case of hyperventilation? Like that was a choice.

But he wasn’t exactly proposing. I read the invitation three more times just to make sure, but there was no declaration of love. It kind of ticked me off.

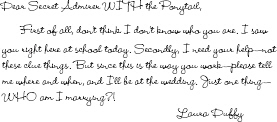

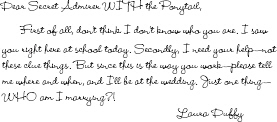

I dug into my backpack, tore out a piece of paper, and grabbed a gel pen. I scrawled in less-than-perfect penmanship,

I folded the paper again and again until it couldn’t get any smaller. Then I stuffed it into my locker and slammed the door.