Chapter 3 Of Winter and Strange Goings On

In the woods most of our time passed in boring hard work. Evenings were the only time for fun, for which we never seemed too tired. Our first shelter was of bark, similar to those we had used at the camp of the Oneida Indians on our way from Schenectady. We stripped great pieces of bark from some birch trees, and laid them over a frame of saplings. After dark we sat round a blazing fire, swapping tales, the taller the better. The Mallorys were craftier at this than Cade and me.

Whenever anyone's gravely ill,” Elisha said one night. “They go see the witch who has a cabin back among the lakes. She can cure better than Dr. Jones.”

“Back there they keep a close watch on their cats,” Jeremiah added. “Or they're likely to end up in her magic pot.”

“Ugh!” Cade said, lip curled in disgust.

“Turned into some sort of potion,” Elisha said. “Unless they're black. Those she keeps.”

“I don't believe all that,” Cade retorted scornfully.

“That's because you're from New York. We're from Vermont, where they've lots of witches.”

Sometimes in the autumn night we heard strange growling sounds. “They're catamounts,” Elisha said. “There are plenty of them on the American side of the river.”

“You mean panthers, mountain lions?” Cade queried.

“Yes, those are other names. In Vermont we say catamount.”

“We think one stalked us while we were coming north from the Mohawk Valley,” I added. “They can be dangerous. We'd better watch out for them.”

“Haven't seen any on this side,” Elisha said. “The river's a barrier. They mostly stay in or close to the Adirondacks or the Green Mountains.”

Often I would lower my axe as the days passed. Of course, I had to ease my aching arms and shoulders, but my real reason was because I admired the view. Jeremiah Mallory said the autumn colours were better than usual, and to me the trees were a picture. The crimsons of the maples, the deeper reds of the oaks, the yellows of the birches, and the deep green of the white pines dazzled my eyes.

“I wish Mama were here to see all this,” I said to Cade as he, too, rested, rubbing his shoulder. “Those islands are like sugar cakes, much prettier than they looked last May.”

“She'll have years to admire this view,” the ever practical Cade observed. “When the house gets built on her favourite spot.”

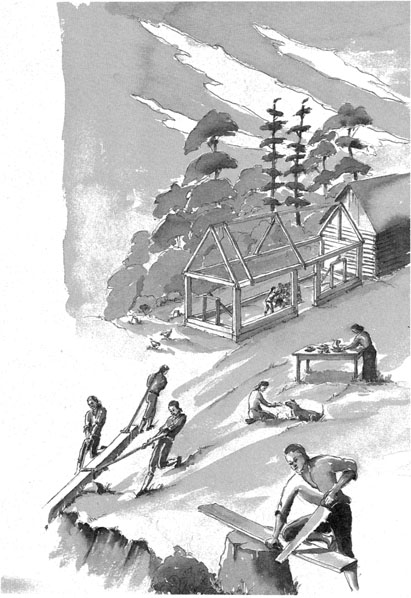

We were careful, when we started building the cabin, to put it off to one side so as not to spoil Mama's chosen place. First came a chimney of loose stones we gathered from the shore. The soil was mostly sandy, but we did find a patch of sticky clay to chink between the stones to hold them in place. The part of the chimney above the roofline was of sticks well covered in clay so that they would not be set afire easily. We chose small trees for the log walls, notching each log at both ends so that they would fit together without leaving too wide gaps. Jeremiah Mallory worked with us, often telling us what to do, though we had helped build the cabin at Coleman's Corners and knew what we were about. Elisha meanwhile was making a large chest, to hold wood ashes for the potash operation. The rest of us used some of the boards brought from Coleman's mill for the cabin floor and the roof. We covered the roof boards with sheets of birch bark to keep out the rain. Sad to tell, we ran out of boards for the door and the shutters for the windows, and had to split logs into boards by hand. In two weeks we had a snug cabin and were making it cosier by filling in cracks along the walls with clay. Otherwise our wants were few though our furniture was rustic. We split some more logs to make bed frames, while thicker logs cut crosswise served as stools and a small table. With the shutters and the door closed, the place was dark except when the fire was high. Even then cold air seeped in around the edges of all openings.

About a week after we had moved inside, the Mallorys told us about buried treasure said to be on land between ours and theirs. The owner of that land was Billa La Rue, who had built a cabin and started damming a stream that dropped swiftly into the St. Lawrence. He planned to build mills once the dam was finished.

“Everyone knows he's hid a fortune in gold coins in the woods,” Elisha said, looking cunning.

“Where would anybody get gold coins these days?” Cade enquired, sceptical.

“There're all sorts of tales about that,” Jeremiah said. “Some say it's King's gold. Billa was a spy for King George during the revolution.”

“Anyway, the only time to look for it is at midnight,” Elisha spoke with conviction. “To make sure old Billa's asleep.”

“But I've heard tell of ghosts,” Jeremiah interrupted. “Do we really want to go at midnight?”

“If Sam were here, he'd be off like a shot to look for it,” I remarked.

“What Sam can do, we can do,’ Cade bragged, unusual for him, I thought. “Why not let's go see if we can find it.”

“How about tonight?” Elisha suggested. “We can leave the fire banked and come back to a warm place. The moon's nearly full. We ought to look before it snows so we won't leave tracks.”

“Good thinking,” Jeremiah said.

Thus we found ourselves marching along, each with a wooden shovel over a shoulder, guided by the shore, the river shimmering to our right. We laughed and chatted till Jeremiah motioned for silence. “The La Rue cabin's just beyond those trees,” he said. “Follow me and keep quiet.”

We moved in single file now, trying to step silently as we circled the trees and found ourselves to the rear of the darkened little dwelling. Not quite sure what we were looking for, we fanned out and some time passed as we examined the ground. At length Cade came to me, the others right behind him.

“There's a place where the ground looks different, as though someone might have dug it up and filled it in again,” he whispered.

“We can try there, but I suspect it's too far from the cabin,” Elisha said.

“Wait,” said Jeremiah. “Try to put ourselves in Billa's shoes. Maybe he'd think it's safer not too close.”

“Let's look there first,” I suggested. “We've nothing to lose.”

The moon throwing an eerie light, Cade led us to the place, and we began to dig. We made quite a large hole and were about to give up when one of the shovels struck something that had a metallic ring. “There seems to be a box down there,” Elisha said.

I was the first to jump into the hole to investigate, and was soon scrabbling with my hands around what seemed a corner of a chest. Suddenly I could not see what I was doing for something large appeared to be shading me from the moon. Next I wondered why none of the others had followed me into the hole, as I turned to see what was shading it.

Towering over me was what seemed to be a huge, silver-hued bull, prancing, horns flashing, but making no sound. In my imagination I could hear snorting as a gust of wind chilled my face. For a moment I was frozen before I fairly flew out of the hole, my feet like wings.

I brushed past a whole herd of shining phantom cattle, prancing silently as I dashed to the shore. Of Cade and the Mallorys there was no sign. On I ran, my breath coming in short gasps, certain I could feel the whole herd hard on my heels, expecting to be gored by ghostly horns at any moment. As I dashed past the La Rue cabin I imagined I heard a sound like a cackle. I made for our cabin, half fearful the others would not be there. Perhaps they had run for the Mallory farm for safety, rather than the empty cabin.

I was so relieved when I pushed open the door to see Cade, poking up the fire, the others behind him. All were close enough to the flame for me to see how ashen their colour was. Gradually my heart stopped thudding in my breast.

“Old Billa can keep his treasure for all I care,” I muttered when I found my voice.

“Sorry I ran out on you,” Cade murmured. “But I was that scared.”

No one slept much during what remained of the night. Nor did anyone ever mention that night nor try to understand what had occurred. That was not the end of the matter either. I was the first to go outside after dawn, and I could not believe my eyes when I spotted four shovels standing in a row against the side of the unfinished potash box. Now I remembered that we had taken them with us, and I certainly had not stopped to find mine before I leapt from that hole. I don't imagine the others bothered to remove theirs either. Did old Billa hear us and spirit them over?

I ran back inside. “Our shovels are here,” I said.

No one answered me. In fact no one said anything at all for hours. We were all happy to see a real human being later in the day when Captain Sherwood rode in, leading a second horse. He was on his way to Kingston and would be bringing his two sons home from school for the Christmas holidays. Soon after he left, Papa and Sam arrived, rowing our new bateau. Like Mr. Buell's, it was about half the size of the government ones that passed by in brigades. It had a mast, but as yet no sail.

We helped them unload barrels, wooden buckets, and a large iron kettle, all purchased from the bit of money Papa had earned working on the Sherwood raft and for the use of the stallion. We all had much to admire, which helped take our minds off the strange happening of the night before. Papa was pleased with the cabin, and we praised Sam for the fine work on the bateau. They were to stay till nearly Christmas, when we would all go home for the celebration.

Papa soon had us making snowshoes, for we would need them to get about once the white blanket lay thick on the land. He thought of them, and the Mallorys knew how to make them. We put long strips of wood for frames in the river and soaked them until they became soft. Then we bent them round and tied the ends together with a deerskin thong. Next came the stringing with more strips of deerskin. We were still employed in this way when towards dusk one evening Captain Sherwood appeared, Samuel and Levius on the spare horse.

“Great things are happening,” Mr. Seaman,” was his greeting.

“Will you stay the night, Captain?” Cade asked him.

“The very thought I had,” Papa said. “You're rather late to try for home.”

“I was hoping you'd invite us. Yes, thank you. We would like a warm spot to sleep.”

“You've grown a lot, Ned,” was Levius' greeting for me.

“And not a bit too soon either,” said I.

During the night heavy snow fell. We asked the Sherwoods to stay as long as they liked, but they set out anyway. “We may not get all the way home in this but I'd like to try,” said the captain.

Once we finished the snowshoes, we had to learn to walk on them. They were awkward until we learned to keep our feet wide apart. Sam's first effort was fun to watch, for he disliked spreading his legs out. He kept setting one shoe on the edge of the other and falling down. I wanted to burst out laughing, but his scarlet face warned me to watch my step. For the first few days I found the muscles of my inner thighs very sore, before I got used to stretching so far.

On the 23rd of December the Mallorys departed for their farm, and we left on our snowshoes for Coleman's Corners soon afterwards. The temperature had fallen, and we decided not to risk the bateau getting frozen into the ice at an inconvenient spot. We shovelled the snow out of it, pulled it well up on the beach, and with much heaving turned it over so it would not get full of snow again. Well bundled, carrying some food, we waved to the deserted cabin and followed the shore.

I shuddered as we passed the La Rue cabin, and I think Cade did, too, but we avoided each other's eyes. It was dark by the time we walked into Buell's Bay, and I wondered how I would ever cover the last three miles. After a bit of rest at Buell's store I felt better and was ready to continue. By now the moon that had shone the night we went treasure hunting had waned, and we could hardly see the road.

“Thank goodness we're nearly there,” Papa said as he almost fell when a snowshoe tipped sideways into a rut.

“Amen to that,” Cade agreed. “I'm bone weary.”

“When we go back, we'll be bringing the stallion and can take turns riding him,” Sam said.

Mama seemed to sense when to expect us, for she opened the door before we could remove the snowshoes. She emerged, moccasins on her feet, wrapped in a shawl, unable to wait till we were inside. The young ones flowed out after her, Elizabeth calling them to come back out of the cold. Finally we were all within, amidst some hubbub removing coats and warming our chilled bodies at the hearth. When the excitement died down, Mama took the floor.

“I have some news,” she announced as Elizabeth nodded.

“We've got a letter!” Sarah chanted, dancing around before Mama could tell us herself. “We've got a letter!”

Trust her to spoil Mama's surprise, thought I.

Papa ignored Sarah. “From whom, my dearest?” he said.

Mama hesitated, gazing at Papa. “My brother William. He wants to visit us next summer.”

“All the way from Long Island?” Sam broke in. “Some journey!”

Papa paid no more attention to Sam than he had to Sarah. “You should write immediately, Martha. Tell William we'll be happy to receive him.”

Mama smiled, less tense. “I hoped you'd feel that way. It's time we healed the breach the revolution made in our families.”

“Is anyone coming with him?” Papa enquired. “He may have a wife and children by now.”

“He'll be alone,” Mama replied. “He says he has never married.”

“Did he say how he found out where we were?” I asked her.

“Zebe told him about seeing us in Schenectady and of how we disappeared in the night. A friend who comes to Montreal on business suggested we might be near Johnstown,” Mama replied. “William sent his letter to our district postmaster in the hope that someone would know us and deliver it. Thank goodness Papa left some money with me, for I had to give Mr. Buell sixpence. He paid the postage and brought the letter from Johnstown.”

“When your reply is ready, Cade may ride to Johnstown and leave it at St. John's Hall, the inn,” Papa said. “The sooner it reaches there the better. Who knows how long it will be before a reliable person is found to carry letters to Albany.”

Thus far Cade had been a mute observer. “I could take the letter straight to the postmaster, Captain Munro,” he suggested. “Samuel Sherwood said his farm's only five miles east of Johnstown.”

“I should have thought of that myself,” Papa said.

Mama's face brightened. “I'd feel easier in my mind if Cade put the letter in the postmaster's own hands.”

“I'll give you some cash, Cade,” Papa said. “You'll have to spend a night somewhere. There and back would be too long a ride for the stallion.”

“Not to mention my tail end after bouncing on his backbone,” Cade rejoined. “When our ship—er, raft—comes in, let's order a saddle.”

Mama found some paper, purchased for the school she kept each afternoon for Smith, Sarah, Stephen and some village children. Papa slipped out and borrowed a piece of sealing wax from Mr. Abel Coleman, the miller and my friend Elijah's father. After Mama folded her letter and addressed it, Papa melted the tip of the wax over a glowing brand. He dropped a little on the edge of the paper and pressed it with his ring, engraved with the letter S.

“I'll go at first light,” Cade promised Mama.

She scarcely heard him. “This place!” she moaned, looking about her in dismay. “Where on earth can we put a guest?”

Papa rose and strode back and forth as he liked to do when he made a plan. “It's high time we had more room. We've lots of our own timber. The boys and I will fetch logs from our land for an addition, and I've enough cash to pay to have the timbers squared at Coleman's mill. We ought to be able to put up a two-room wing before the summer work. One will be a parlour, the other a bedroom for visitors.”

Mama put her arms around him, shaking her head. “You haven't time. We've new orders for the shop, and what about your plans for the raft?”

Now it was Papa's turn to shake his head. “We'll make time, my love. I won't have William going back to Long Island saying I'm not able to provide you with a decent home.”

Still Mama had doubts. “Suppose we do finish an addition. Will we have time to make more furniture?”

Of course,” Papa said cheerfully. “I wish we could hire a cabinet maker but I'd have to borrow money to pay him.”

“We mustn't go into debt,” Mama said in alarm. Then she had an idea of her own. “Sam, do you think you could turn out some nice pieces?”

“I'd like to try,” Sam replied. “I know I can go to Mr. Buell if I get stuck. He's a cooper by trade.”

Mama sighed happily. “More room and the thought of William's visit will make this winter fly by. It's lovely to have something special to look forward to.”

Cade was gone overnight taking the letter to Postmaster Munro's house. When he returned he proudly handed Papa some coins. “I didn't need much,” he said. “I bumped into Samuel Sherwood and he invited me to spend the night at his house after I'd been to the postmaster's.”

“How's Levius?” I asked.

“Groaning over his Latin. The schoolmaster at Kingston ordered him to work on it during the holidays for he's way behind in it.”

“Poor fellow,” said I. Being not so well off had its bright side. If Papa could have afforded it, he might have sent me to school, as he had done in Schenectady.

On Christmas day we held a special service in Coleman's barn, which was warmer than Boyce's field. I was less enthusiastic about our feast that followed. Before he left for our land, Papa had butchered the pig the McNishes had given Cade. We had made a pet of it, and I thought we had lost a friend.

“I feel like a cannibal,” I whispered to Cade as Papa began carving the roast that reposed on a wooden platter he had made.

“You're too tender-hearted, Ned,” he scolded softly, hoping no one would notice us. “Papa had to kill it for we don't have enough scraps from the table. We never leave anything on our trenchers, and we've nothing else for feed. We'll be lucky if the chickens, ducks and horses don't starve before spring.”

The work party that returned to our land was comprised of Papa, Sam and myself. Cade was to have a turn looking after the shop and helping Mama. With Papa there, Sam and I wouldn't get into many fights. We were delayed by heavy snowfalls early in January. When we finally did set out Papa was leading the stallion, our supplies packed on his back. We would not be riding him, to Sam's disgust. The snow lay so deep that even with snowshoes we sank down and found the going tough.

Now, joined by the two Mallorys, we began felling the trees in earnest. Each had to be chopped down with axes, then stripped of branches with our saws. Afterwards, driving the stallion, often with most of us pulling to help him, we moved each huge log close to the river shore. From there we would in time move the logs into the water a few at a time, and bind them together securely with long, pliant willow strips the Mallorys called “withies”.

February was bitterly cold and my toes got frostbitten. I had to stay inside for a few days, and Papa set me to brewing batches of spruce beer. We had trekked some potatoes and carrots from Coleman's Corners, but to save weight we had brought molasses and yeast, traded with Mr. Buell. The recipe was the one Mama had used to prevent scurvy during our first winter in Canada.

I heated about two pounds of spruce tips and two gallons of water in a cooking kettle. After it boiled I removed the spruce, added molasses and yeast to the liquid, and set the kettle near the hearth to ferment. The beer was a time-honoured method of warding off scurvy, learned from the Indians, and was every bit as good as fresh vegetables. I didn't care for the taste, but making it gave me something to do till my feet got better.

Early in March, a silly accident put an end to my life in the woods for some weeks. I, who had done very well with an axe cutting down huge white pines, let it slip while splitting kindling. The blade gashed my right foot, and a frantic Papa left Sam working with the Mallorys to take me home. After wrapping the foot to stop the bleeding he set me on the stallion and led him towards Coleman's Corners where Mama could give me the care I needed. I crossed my right knee and propped my injured foot in front of me. If the leg hung down it throbbed and Papa was afraid it would bleed again.

I felt about spent by the time we reached home. Mama, to my surprise, seemed to be watching for us though we were not expected. In jig time I was lying on my parents' bed, my wounded foot stripped of Papa's bandage and propped on two pillows. Mama squinted at it, brow furrowed. Beside her Elizabeth was looking all sympathy.

“Fetch my sewing basket,” she said. “This needs stitches.”

At that I could not keep from shuddering!