Chapter 6

Apprentice Raftsmen

As I rode along the track that roughly followed the river I felt a new sense of freedom. The mist of dawn was lifting and the colt frisked about, I was happy alone after having been cooped up at Coleman's Corners for so long. The time was now early September 1791, and Papa had told me Cade and Sam had harvested most of the grain and vegetables they had planted in the spring. They had planted cuttings from the old apple trees, but some years must pass before we would have our own fruit.

I stopped at the Mallory farm to rest the mare and allow the colt to suckle. Jeremiah and Elisha were at home with their parents, Mr. and Mrs. Enoch Mallory. During the summer and early autumn they had too much work on their own land to help us prepare logs. They offered me a meal, but I accepted only some cider since I had brought plenty of supplies. As I passed Billa La Rue's cabin, I did not see anyone round. I wondered again about the strange events of that moonlit night last autumn.

Sam was working on a huge trunk with his axe when I arrived, and near the cabin Cade was keeping watch on the potash kettle, slung over a fire. I was mystified until he explained what he was doing.

“We collect ashes from burnt branches and put them into the wooden chest. See those holes at the bottom of the chest? Below them we set buckets, and then we pour water into the chest in top of the ashes and let it soak through them. What comes down into the buckets is called lye. We boil it down to make it more concentrated. Then we put it in barrels which the brigades pick up and take to the merchant in Montreal who buys it from us.”

“I suppose I'm to take over from you, “said I, and I told him of Papa's order to take the bateau to Buell's Bay.

“I'll be glad to go,” Cade told me. “My shoulder's bothering me again, and I've had to leave the heavy work to Sam. I think you should help him. I can finish this batch before I leave here,”

“I expect you won't be able to do much in the shop,” I remarked. I hoped that Papa would not have many orders or he might send me back to carry on.

“I'll be fine in the shop. I only use my good arm while handling the heavy hammer,” Cade explained. “For chopping and sawing I need both arms.”

He set off the next day, with a new sail up in a southwest breeze. Sam had made the sail out of some old canvas he found on Grenadier Island. “I suppose it was left there during the revolution by some ship of the Provincial Marine,” he said.

Right after Cade left, Sam lived up to his old reputation for laziness. He went off to a new clearing on the next farm lot to the west, which belonged to a family named Smith. I was left to chop by myself, and he did not reappear until nightfall. The next day, however, he stayed, working hard. He did not know at what time to expect the bateau, and if he were missing when Papa showed up he would be in deep trouble.

I thought Uncle William's visit to our land would be the highlight of the autumn, but I turned out to be mistaken. We did give Mama and Uncle a fine reception. Uncle was suitably impressed with our trees and he did exclaim over the rustic cabin. He did admire the view of the islands, and he did not complain about sleeping in the bateau, his skin smeared with oily horse balm to ward off mosquitoes. And Sam did take him hunting and return with a fine buck deer. All these activities, delightful though they were, were overshadowed by the arrival, a fortnight after Uncle, of Captain Sherwood in his canoe. He had a special request to make of Papa.

“Mr. Seaman, my young cousin, Reuben Sherwood, has a raft ready to sail for Quebec. He's short-handed, and I think this is a fine opportunity for your sons to learn rafting before you take your own down the rapids.”

Papa, leaned on his axe and wiped his forehead as he thought a bit. “We do have a lot going on, Captain Sherwood,” he began. “But I think you're right. I won't be sailing with such a green crew next year if some of my boys get experience now.”

“Good,” the captain replied. “I'd like to leave with them at first light. Reuben's land is the west half of Lot Two, on the river a mile below Buell's Bay.”

“Sam and Ned may go,” Papa said, to my joy. “My eldest son's at Coleman's Corners and we don't have time to send for him.”

I could hardly contain myself, and Sam fairly roared with delight. Riding a timber raft promised the sort of excitement he craved. I knew he was dependable when he liked what he was doing, and I had no qualms about going with him. We were both in high spirits when we bid Mama and Uncle and the others goodbye the following dawn. Armed with food, warm clothing and blankets we joined Captain Sherwood in his canoe.

At first, Sam paddled in the bow, then I had a turn. I was surprised at what good time we made in the sleek craft., aided by wind from the southwest and the current of the St. Lawrence. We passed Buell's Bay in the late afternoon and soon spotted the huge raft tied to some trees that grew below a sandstone bluff. Since there was no beach, we tied the canoe to a jetty. On the raft I noticed a small log cabin for shelter, and a tall mast.

“Hallo, Reuben,” Captain Sherwood shouted. “Hallo!”

Before long a hefty young fellow with broad shoulders, a thatch of unruly fair hair over bright blue eyes, came down steps cut into the cliff and joined us on the jetty. “So, Cousin Justus,” he said. “You've brought me crew.”

“As I promised,” the captain rejoined. “Sam and Ned Seaman. Samuel and Levius will join you in good time tomorrow morning.”

This adventure was proving even better than I had hoped. We would have good companions, and I liked the look of Reuben, who seemed hardly older than Sam. Captain Sherwood waved as he slipped into his canoe to return to his farm in Augusta Township, a short distance farther downriver. Reuben had us stow our things in the cabin on the raft and invited us to supper. He led us up steps cut in the bluff to a humble cabin, not as big as the one on our land. He lived alone, he told us. His father, Ensign Thomas Sherwood, owned the next farm to the east,

“I was in the ranks of the Loyal Rangers when I was fourteen,” Reuben explained. “We moved here after the revolution. At first I lived with my parents and studied surveying with Cousin Justus, and helped build rafts. I only started pioneering on my own land last spring.”

His cabin delighted me. It was filled with the kind of clutter I longed to leave about, which Mama always insisted I tidy up. The meal was baked beans, swimming in pools of grease and chunks of pork, as sweet as sugar. Reuben must have put more molasses in his beans than Mama would allow. I thought them delicious, just right for my sweet tooth.

When we were ready to settle down for the night, we carried armfuls of cedar boughs to the raft, laid them on the logs inside the cabin, and spread blankets over them. The night was clear and dry, and we took our bedding outside and slept under the stars. The shrill call of a bluejay rocking on a weeping willow bough woke me. The sky was grey, but a tinge of light in the east showed that dawn was not far off. Before long sounds coming from the cabin atop the bluff told me that the rest of Reuben's crew had arrived. We tidied up our gear and climbed the steps in search of breakfast. Levius Sherwood was there, cooking bacon and eggs in a pan over a fire outdoors.

“Hello, Ned,” he called. “Glad you could come with us.”

Samuel Sherwood seemed pleased to see our Sam. Tagging after him was a lad of twelve. “Reuben's brother Adiel,” Samuel said. Then he called to a large black man who was arranging some of their belongings. “And this is Scipio, who came from Vermont when we did.”

“Scipio's come to keep us all in line,” Levius said with a wink. “Pa's sent him because he's sensible and Reuben's only twenty-two.”

“Young but experienced,” Reuben retorted. “Do you think my Pa would risk Adiel if he thought I wasn't dependable?”

We tidied up after breakfast, and Sam and I helped the Sherwoods stow their belongings in the raft's cabin. Next, Reuben showed us how to hoist the sail and cleat the sheets. Scipio shouted the orders that sent us to untie the various mooring lines. I knew he was a slave, but he acted as though he was accustomed to giving orders and to having them obeyed promptly.

Once we were under way we had little to do and I was able to study the shore. To my surprise I found a friend paddling a canoe as we swept along. It was Mr. Truelove Butler, who had accompanied us on our journey from Schenectady after we escaped from the jail.

“How are all the Seamans?” he called out.

“Very well indeed,” Sam replied. “When can you visit us?”

“One of these days I will,” he shouted back.

Soon Levius pointed to a large square-timbered house above the shore. “Our place,” he said, waving to a woman standing on a jetty. “That's Ma, come out to see us on our way.”

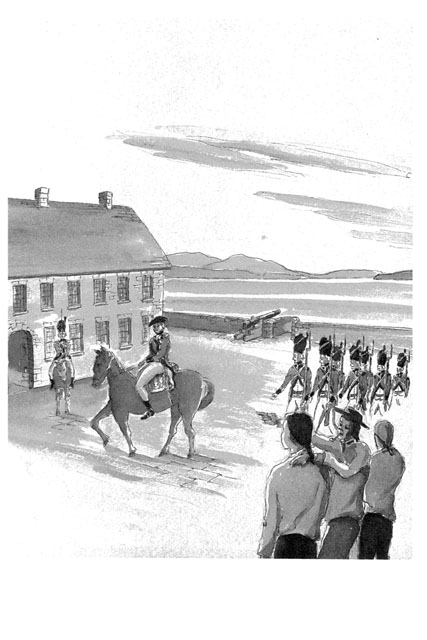

Before long we passed Fort Oswegatchie, on the south shore, with its memories of the British regular soldiers who had helped us cross into Canada. Next, on the north shore we saw Johnstown, the village of wooden houses that was our district seat. Our magistrates held court four times a year at St. John's Hall. A fleet of bateaux lay alongside the docks, and a tall sloop rode at anchor near the channel. I remembered our arrival here after our escape from Schenectady, and Mama's dismay when she caught her first glimpse of Johnstown. It did not look much different today. My thoughts were interrupted by a shout from Reuben.

“Galop Rapids ahead. Lower canvas!”

Scipio steered at the rudder while Reuben and Samuel Sherwood showed us how to loosen the halyard and keep it from tangling as the sail slid onto the log surface below. The drop down these rapids was gentle, eddies swirling along the sides of the raft. The sensation of speed was not alarming. Again at Rapide Plat the drop was gentle and we enjoyed the ride. As we were passing a large flat island I noticed we had slowed down. I helped hoist the sail again, and afterwards Reuben handed out chunks of bread and mugs of cider. Towards dusk the current was carrying us forward more rapidly Again we dropped the sail and for the second time Reuben shouted a warning.

“Long Sault ahead. We'll tie up here for the night.”

Scipio guided the raft gently alongside the bank in a sheltering bay. We crew members then had some busy moments, leaping ashore and finding suitable trees to which to tie the mooring lines. In the distance downstream we could hear the rumbling of the Long Sault. I already knew they were formidable, and dangerous.

For supper we caught some fish. Scipio made flat cakes of flour, eggs and water and fried them in a pan over glowing embers. I made a spit of green branches and skewered the fish before roasting them. That night we made our beds up round the fire and took turns keeping it going. The air had turned chilly.

Voices from the water roused us. A party of Indians in two long canoes was approaching our camp. Reuben was already up, which made me suspect he had been watching for our visitors. All of us rose to our feet, absorbed by the picture they made as they drew their canoes up on the flat shore.

Reuben nodded towards the newcomers. “Pilots for the trip down the rapids,” he explained.

“How did they know we'd be here?” I asked, bewildered.

“Scouts,” Reuben replied. “It's always the same. A raft arrives and there they are, Johnny on the spot. They're Mohawks from St. Regis, across the river. Sure footed as mountain cats. They like to earn hard cash guiding rafts through white water.”

We gave the Mohawks some tea, and they sat cross-legged in a circle, smoking their pipes while we had breakfast. Afterwards we helped them fell eight small trees and strip off the branches. Next they made a square crib, lashing the logs firmly together with withies. I watched carefully as they handled the long willow sinews. I would have to learn to twist them and tie firm knots myself before long. Then all the pilots began walking downstream along the shore. Sam and I followed until we could see the rapids, boiling and surging over the wide riverbed. Below us one of the Mohawks stopped, and the others kept on walking.

“We'd better go back,” I said reluctantly, for I wanted to see what the Mohawks would do next. “In case Reuben has anything he wants us to do.”

I must have looked confused, for when he saw me Reuben laughed and thumped me on the back. “The Mohawks take up positions all along the shore,” he said, pointing towards the rapids. “After we release the crib, they watch were it goes. That's the safest path. Then they come aboard with us. Each pilots the raft through the stretch of white water he watched, following the path the crib took.”

We waited and waited, until one of the Mohawks came to tell us the others were in position and we should release the crib. Everyone helped lever it into the water. Slowly it floated in the direction of the rapids, leapt forward, and vanished. Another long wait followed, until all the Mohawks came back. Now even Sam was looking anxious as we released the mooring lines and the raft began to move.

The guides seemed very cool. “Don't worry,” the one holding the rudder said when we suddenly picked up speed. “We've never lost a raft.”

I was not reassured. The roar of the water soon drowned out all conversation. Rolling waves towered above our heads, and I was convinced the waters would engulf us. We rose and fell, swung and swerved, the noise deafening. I was so busy hanging on that I scarcely noticed the Mohawks calmly changing places at the rudder, others nimbly running about with poles. The nightmare seemed never ending, but it probably lasted twenty minutes at most.

Then the danger was past as suddenly as it had begun. The raft moved slowly over smooth water. The pilot steered for shore, and I swayed as I stepped on Mother Earth, a mooring line in my hand. Sam, coming to his senses first, bent and kissed the ground.

“Whew!” he exclaimed. “Thank heaven that's over!”

Since he always appeared braver than me, I was glad the ride had unnerved him, too. After we tied up we all went to thank the pilots. Reuben went among them, shaking each man's hand and giving him some coins as he expressed his thanks.

“You bring the rafts,” one of the Mohawks said, head held high. “We'll get them through safely.” I thought he had every right to take pride in having such a useful skill.

The rest of the journey was fascinating, and I no longer had cause to fear the rapids. Each night we camped ashore or aboard the raft, fishing to add to our food supply. We floated across Lake St. Francis to the head of the Cedars Rapids. Again a crew of Indians built a crib and helped us steer the raft through them, and through the Cascades just below them. By that time the weather had turned piercingly cold on the water, and I bundled into all my extra clothes. We were now moving down Lake St Louis towards the Island of Montreal. At the Lachine Rapids yet another crew of Indians appeared on cue. Then we were sailing past Montreal itself, tumbledown stockade beside the shore, church spires in the distance, schooners and brigantines at anchor in the harbour.

“How I wish we could stop and see the city,” I said.

“We will on our way back,” said Reuben. “I've a list of things I must buy for myself and others. The timber merchants pay us in hard cash, and we always do our shopping in Montreal after we've sold a raft.”

Off Sorel, at the mouth of the Richelieu River, we had to be careful for a bit. A maze of low islands almost blocked the channel, and the water ran a little more swiftly. That spot was known as the Richelieu Rapids though they were nothing compared to the Long Sault, Cedars, Cascades, Lachine or even the gentler Galop and Rapide Plat. Ships were able to sail up the Richelieu Rapids to Montreal when the wind blew from the northeast. No one could take a ship upstream against any of the other rapids, no matter where the breeze came from. As we sailed, Reuben pointed out several important landmarks so we would find the right channel when the time came to sail our own raft. Below the Richelieu Rapids, as we entered Lake St. Pierre, several vessels were tacking about.

“They're waiting for the right wind to push them up the rapids,” Reuben said.

On this lake sail and current carried us slowly past flat farmlands, and on to a large town. “Trois Rivières,” said Samuel Sherwood.

“Three Rivers,” Levius added. “Samuel likes showing off his French.”

“That's where our iron comes from. From the forges of the St. Maurice,” said our Sam. “But it's awfully expensive.”

“Our Pa says there's lots of bog iron north of Elizabethtown and we ought to be mining it,” Levius remarked.

“That would be a godsend,” our Sam said.

We left Lake St. Pierre and soon walls of rock towered above us. Fortunately we always found a ledge with trees on it where we could secure the raft. “We're almost there,” Reuben called when we had been sailing eight days since leaving his farm. “That's Wolfe's Cove on the left. Plains of Abraham above. Quebec's just ahead.”

I looked up but nothing told me the city was at hand. The shore was steep, a vast mountain of rock that left us sailing in icy damp gloom. Without warning we rounded a bend and there lay a harbour lined with buildings and wharves. Ships with sails furled lay at anchor—big ones with many masts and yardarms, much larger than any that passed our land.

“What enormous ships,” I said to Reuben.

“First rate ships of the line, those big ones,” he said. “They're Royal Navy. Beauties, aren't they?”

The harbour front was alive with uniformed men, red-coated soldiers, sailors in blue with loose white trousers. Many bateaux lay alongside the wharves, but Reuben found space for the raft. I noticed some boats like bateaux but larger as we tied up. Durham boats, Levius told me.

“Rum for all hands,” Reuben called, beckoning to us. “Can't risk anyone coming down with pneumonia.”

The stinging stuff made me choke and burned my throat. It warmed me right to my toes, though. Adiel, too, spluttered over the fiery drink, but the blue tint left his face. He grinned at me. “My first trip. I've wanted to come for ages.”

“The nice part's the city,” Levius said, cradling his rum with both hands and breathing the fumes. “We'll have lots to do while Reuben and Scipio are busy with the timber merchants.”

“Tonight, we'll have warm beds at the London Coffee House,” Reuben announced. “We deserve some comfort after so many nights outdoors.”

He pointed to a vast stone building with white wood trim and a red tiled roof. It faced the wharf with its back against the rocky cliff. Once our raft was secure we gathered our belongings and hurried to the hostelry. Inside, when Reuben ordered beds, the landlord looked us over.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Room for six and a place in the stable for the slave.”

“No,” said Reuben. “Our servant must have as good a bed as you offer any of us.”

“As you wish, sir,” the landlord replied with a shrug. “A room for seven.”

We were shown into a large chamber that actually had four wide beds in it, enough space for eight. The next thing that caught my eye was a giant teacup complete with handle under one of the beds.

“What's this?” I enquired, drawing it out.

Sam laughed. “Oliver's skull! I haven't seen one in years.”

At my puzzled look Reuben took charge. “It saves going to the privy by the stables during the night. The servants empty it.”

“The correct word is chamber pot,” said Samuel Sherwood. “The nickname was an insult to Oliver Cromwell because he ordered King Charles the First's head chopped off.”

“I wondered how it got that name,” our Sam remarked.

After stowing our things we went to the dining room where a blazing fire from the hearth cast a cheery glow. The warmth was what we needed after days out in the cold. All around us people were speaking French, and we caught only the occasional bit of English. A good night's sleep followed, and we five lads were ready to explore Quebec. Samuel and Levius would serve as guides. Adiel was as keen as Sam and me to see the greatest city in the country.

Over breakfast, Reuben told us we need not hurry. “You'll have all day. The merchant we've chosen is a hard bargainer, isn't he, Scipio?”

“You're a hard bargainer yourself, Mr. Reuben,” said the black man. “It's your Yankee roots.”

Breakfast over, we climbed the steep flight of stone steps that led from the Lower Town to the more opulent Upper Town. On top of the rock, the governor's residence and the finest houses and shops were to be found.