Chapter 8

Tryst on the Hudson

At home we found everyone but Papa and Cade, who were upriver on our land. “Papa wants you and Sam to leave as soon as you can, with the filly so he can school her more,” Mama told us. “He's worried that he may not have enough logs cut before the spring work interferes.”

“Don't you need one of us here, Mama?” Sam asked her.

“We've been managing very well so far,” she answered. “Uncle is very good at showing Smith and Stephen what needs to be done.”

“Tell us about the cow,” I asked next.

“We can thank Uncle, and also Captain Meyers, who stopped in his boat at our estate before we left for home,” she replied. “He has been bringing cattle in from Oswego. William went to the Bay of Quinte with him and brought the cow on the next brigade coming east. She'll have a calf in the spring so we'll have fresh milk again next year.”

That winter of 1791-1792 all our efforts went towards having enough logs for the great timber raft. While Sam and I had been away with Reuben, Papa and Cade had been busy erecting sheds on our land so we could store enough grain and hay for the horses. The grain was from our own stump-strewn fields, and the Mallorys had used our bateau to carry most of the hay from Coleman's Corners or their own farm. Samuel and Levius Sherwood and their father spent a night in our cabin on their way to Kingston. Everyone but Cade walked home on showshoes for Christmas. He stayed to look after the horses. The rest of the time was sheer drudgery, as we chopped, sawed and hauled logs close to the shore, and burned brush ready to make potash. We did not work the mare too hard, for she was again in foal.

With the spring, Papa sent the mare home with Sam. He would attend to her when she dropped her foal, and also to the cow when her calf came. I stayed until nearly the end of May, then I left to help dig and plant the garden at Coleman's Corners. Meanwhile, the mare had outdone herself by dropping twin fillies, and the cow had a fine bull calf. After the planting was nearly finished on our land, Papa returned, and Uncle William began making suggestions as to when he should leave for Long Island. One evening, as Papa and Uncle sat at the butternut table, lighting their pipes, Papa made a startling suggestion.

“William, how would you like to have Martha go home with you for a visit?”

“You know I would,” William said promptly.

Mama, seated by the hearth doing some mending, looked up. “I can't leave. There's too much work to do here.”

“Oh yes you can,” Elizabeth joined in. “The rest of us can do what needs to be done here. I think it would be lovely for you to have a holiday, Mama. Sarah's more use these days. Now that Margaret's weaned, there's nothing we can't do without you.”

“A journey like that could cost ten pounds, maybe more,” Mama said, shuddering. “Think of how far that sum would go towards the house you long to build on our estate. Besides, we don't have that much.”

“Yes, we do,” Papa said. “I have my potash money and a buyer for the two-year-old filly. Now that we have the new twin fillies, I'm not sure we can winter so many horses. I think it wiser to sell her this season.”

“And,” said Uncle William. “I would be happy to pay part of the passage. After all, you've fed me these many months.”

“No, thank you, William,” Papa was firm. “I accepted the cow, and that's more than generous.”

“One of the boys will have to come along, to escort Martha home,” Uncle pointed out.

At that I pricked up my ears. Which one would Papa choose? Cade deserved the holiday the most, and he did have the bad shoulder. Papa's answer was what I really wanted to hear, though I did feel a pang of guilt for my two elder brothers.

“I can spare Ned the best. In away I would prefer to send Cade. He's worked so willingly for so long. But I really can't do without him at this time of year for he is the best farmer in the family. And I need Sam to school the horses and help in the shop.”

“When shall we leave?” I asked eagerly.

“As soon as you are ready, and there's a brigade going to Montreal.”

“It sounds as though you've made up my mind for me,” Mama said. “And I accept. Seeing my relations will mean so much to me. Thank you all for being so thoughtful. But I can't go just yet, not till I make some clothes.”

Elizabeth helped her, and they sewed me a coat and waistcoat of linsey woollsey. With my deerskin breeches I would have suitable travelling clothes. Uncle said he could loan me a suit or two to wear when I met relatives on Long Island. Mama made herself a gown of the muslin Uncle had brought, and a cloak from her length of red velvet. She made linen belts with many pockets to wear under our clothes. There we would each carry five pounds. Mama was determined, should we be set upon by footpads on our return journey, not to be left destitute. Our other baggage was two carpet bags borrowed from the Colemans, and two blanket rolls since we would be camping part of the time to save money.

Before we were ready to set out, a notice posted at Coleman's mill called upon all able-bodied men to muster on June 4th for militia drill. On the 3rd, Cade and Sam arrived from our land. Now that Sam was sixteen, he had to join Cade at Buell's Bay. We owned two rifles and a musket, and my brothers began to argue over which would take the better rifle. Papa settled that in a hurry.

“Cade may take the musket. Sam will make do with a broomstick.”

“But Papa!” Sam protested. “The militia order says we're to take firearms.”

“Not our precious hunting rifles,” Papa retorted. “Any old stick is good enough for drill. If the Americans should decide to attack us, I'd hand over the rifles, but I don't want to risk having them stolen or taken from you by some British officer.”

After dinner on the 4th a gang of us walked to Buell's Bay. Elijah Coleman, Jesse Boyce and I went along to watch the show. Cade and Sam, and Dave Shipman, would be drilling. When we arrived, we found confusion reigning in Mr. Buell's pasture. Captain James Breakenridge, a half-pay officer responsible for raising the battalion, was trying to bring order out of the chaos. Mr. Buell was the captain in charge of a company being formed. Mr. Mathew Howard was the lieutenant, and Reuben Sherwood the ensign. Mr. Buell asked Sam to be a sergeant, though Cade was older.

Cade was not offended. “Childish,” he murmured, leaning on the musket. “What a waste of time! Half of them've had too much rum already.”

Mr. Buell—I could not think of him as Captain—shouted several times for quiet. When he got it Captain Breakenridge lined up the men. I lazed about watching while the officers argued over what to do next. Reuben came over to speak to me, though he was supposed to be helping Mr. Buell.

“Goodness,” I remarked. “Were the Loyal Rangers this lax?”

“Almost,” Reuben answered cheerfully.

“Did you fight any battles?”

“Nope. I cut hay for the army's horses and stood guard.”

“Ensign Sherwood, remember you're on duty,” Mr. Buell shouted. “Take a party and hold the right flank!”

Reuben chose Cade and five others and concealed them in a gully beside the pasture. Captain Breakenridge divided the other men into two lines, Mr. Buell in command of one line, Mr. Howard leading the other. Sam and Dave were with Mr. Howard. Mr. Buell's force was to attack Mr. Howard's. With much shouting of “bang bang” for want of bullets, Mr. Buell's line marched towards Mr. Howard's. Suddenly Reuben's men, with Cade, appeared behind Mr. Howard's line, all of them yelling “bang bang”.

“Surrender, Lieutenant Howard,” Captain Breakenridge called out in disgust. “You're surrounded.”

“Ensign Sherwood has won the day,” Mr. Buell crowed.

“Unfair,” Mr. Howard shrilled. “Hitting us in the rear.”

“Where was your rearguard?” Captain Breakenridge scolded him. “Lie down, you're all dead.”

Sam, among those “killed” came running over, full of admiration. “How'd you learn that, Reuben?”

“From my Pa. He loves talking battle tactics.”

More drilling in line followed before the militiamen were dismissed. Mr. Buell announced rum for half price at his store, and the men surged towards it in a wave. Sam was in the forefront, Cade desperately trying to catch up with him, me pushing after them both.

“Don't,” Cade advised Sam. “Papa wouldn't approve.”

“Just one drink,” Sam begged. “I'm so thirsty.”

“Very well,” Cade conceded. “Against my better judgement.”

We elbowed our way to a keg, where each of them accepted a tankard. Cade soon handed his half-finished drink to another man, and we went looking for Sam, who had vanished. We found him outside, lying under a tree, an empty tankard in one hand, singing at the top of his lungs.

“Help me lift him,” Cade said, handing me the musket. “The walk home will do him good.”

I stuck my arm through the musket's strap and grasped one of Sam's arms. Then Dave, Elijah and Jesse appeared and the five of us raised Sam up and propelled his dead weight before us. He was steadier before we reached home, but Papa was not deceived.

“He only had one rum, Papa,” Cade explained. “But it was a whopper, not the tot you'd pour.”

Papa called for strong tea, and Mama brought it, looking very upset. Cade and I, ravenous, tucked into a huge supper, but Sam sat with his head in his hands. Over and over he kept murmuring, “Never again!”

“Demon rum! Such strong drink is dangerous!” Mama scolded.

“Next time, come away as soon as you are dismissed,” Papa admonished. For once he was being gentler than Mama. “Don't linger when hard spirits flow.”

“No fear, I won't,” a contrite Sam promised.

Our hunger satisfied, Cade and I told Papa about the skirmish Reuben had won. He roared with laughter, but Mama was not amused.

“Your father and I have lived through the horrors of war,” she said. “I can't bear to think of any of my sons being killed or wounded.”

Elizabeth sided with Mama. “I wish you'd stop. You have to drill, Dave, too, but we don't find your story very funny.”

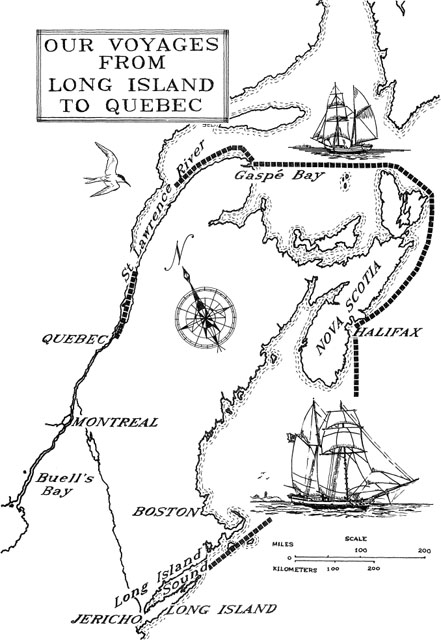

By the third week of June, all was in readiness for our journey to Long Island. We only awaited the arrival of the brigade of bateaux. We finally left on the 26th. Cade and Sam were already back on our land, but Papa had been detained because of orders for the shop. When word that the brigade was approaching reached us, we carried our baggage in the cart, pulled by Dave Shipman's horse. The mare and her two foals, and the stallion were with Cade and Sam. Only the yearling colt was at Coleman's corners, for the filly had gone to her new owner. When we arrived at the jetty there was no sign of the brigade. A man who had ridden in from the west told us we shouldn't have to wait more than an hour. We passed the time chatting, but when the boats hove into view, Mama was looking doubtful.

“Are you sure you'll be all right?” she queried.

“Of course,” several voices answered in chorus.

I found a bateau that had lots of room. Papa handed down the bags and blanket rolls. Uncle took Mama's arm and guided her to a bench under an awning. I stowed our things with the mass of bales, barrels and sacks that were piled aft. After hugs and kisses, we pushed off. From the jetty the family waved, all smiles, putting on a bold front, I knew.

“They're doing their best, the darlings,” Mama voiced my own thoughts. “Well, it's too late to back out. Now we've finally started, I do feel better about leaving, and I am going to enjoy myself.”

“Good,” said Uncle.

The brigade tied up for the night at Johnstown. I suggested Mama sleep at St. John's Hall but she declined. Papa had been generous, bat she was determined to bring back as much cash as possible. She bedded down under the awning with two other women. Uncle and I took blanket rolls and curled up near a fire on shore with some other men and boys. The night was warm, but the smoke helped keep the mosquitoes away.

“I think I've changed a lot,” Uncle said sleepily. “A year ago I would never have dreamt of sleeping outdoors, and I'd have demanded a room at the inn.”

At dawn I caught two fine pike, which we cooked over our fire. Mama, who had the knack of looking at home anywhere, squatted by the coals, holding out a pan. Soon she served us delicious fillets. Then we were off again. Below Johnstown lay Ile Royale where stood an old French fort. As we approached we made out several canoes and a bateau with a Highland piper playing in it. In one of the canoes was Reuben Sherwood, dressed in a green military coat. Paddling in the bow was an older man, also in a green coat, whom Reuben introduced as his father, Ensign Thomas Sherwood.

“What's happening, Reuben?” I called out.

“Governor Simcoe and his escort have arrived, on their way to Kingston,” Ensign Sherwood replied, as the canoe glided in beside us. “We've turned out to greet him, in our uniforms. He asked to be taken to the fort on lie Royale to see if any of the cannon the French left can be cleaned up and used.”

Farther along, we encountered three bateaux coming upstream. When they got close enough we could see a tiny lady with a large beaver hat over very black hair in the lead one. She was sitting serenely doing embroidery. Others in the brigade began clapping and set up a chorus of, “welcome Mrs. Simcoe!” She nodded and smiled, and the moment passed. The third bateau was piled high with baggage. In the second one some servants sat, and a small girl was running from one side to the other, while a nurse cradled a baby about the same age as our Margaret. Mama enquired who they were, and the nurse responded.

“These are the governor's children, Miss Sophia and Master Francis Simcoe.”

We soon had other things to distract us as the bateau slid down the Galop Rapids. It danced about far more than Reuben's heavy raft, which left me dreading the thought of the Long Sault. When we got there the boat flew up and down, and the crew frantically worked with setting poles. Several times we shipped water. The crew tossed Uncle and me leather buckets and we bailed, gingerly emptying them over the heaving gunwales. Mama clung to the bench, face set, until we reached smooth water.

“I'd never get used to that ride in a million years,” she said. Slowly the colour returned to her cheeks.

After a night at an inn in Montreal, we took a ferry to the south shore of the St. Lawrence. There we caught a stage for Fort St. Jean, a large army post on the Richelieu River. We slept another inn and rode eight miles by wagon to Ile au Noix, a fortress near the entrance to Lake Champlain. There we were in luck for a schooner was about to sail southwards. Flinging our baggage out of the wagon we raced to a ship's boat for the ride out to the schooner. An officer showed Mama into a cabin where several other women were quartered. Uncle shared one with other men, but I chose the fresh air on the rear deck.

The wind blew from the south. In the narrow lake the schooner rocked, tacking back and forth, crew bellowing as they trimmed sails. We could see each shore, and the ship had to work its way among several large islands. On both sides of the lake were outlines of high mountains, the Green Mountains of Vermont and the Adirondacks of New York, Uncle told me.

A day and a night of sailing and we reached the ruins of a very large stone fort. “Ticonderoga,” someone said. “Destroyed by the British during the revolution.”

Here the lake was very narrow, and a fleet of bateaux awaited the schooner. A short ride and we had to get out and walk. Rapids lay between us and Lake George, another long, narrow waterway that stretched into the heart of New York State. From Fort George, at the foot of this lake, we found we would have to wait a day for a wagon to take us ten miles to Fort Edward, on the Hudson River. I suggested we walk, and Mama was game. Burdened as we were, not only by bags but by the heavy coins in our money belts, I soon had second thoughts. Three very weary travellers reached an inn at Fort Edward that night. From there a sloop took us to Albany, now the capital of the state.

Albany was a shabby place compared to Montreal. A few wharves lay at the base of a steep bank. Uncle arranged for us to finish our journey aboard a sloop due to depart in two days' time. We clambered up the bank, passed through an opening in an old stockade, and made our way to the High Street. Now I was among familiar surroundings for Albany looked almost like Schenectady. The same tall houses overlooked wide grassy streets where cows grazed and pigs rooted. What a contrast this was to Coleman's Corners, where the houses were squat and far apart and fences confined the few cows and pigs.

Uncle led us to the inn he had used while on his way north. Mama shared a room with four other women, Uncle and I with two men and two boys. The night before we were to sail we were seated round a vast table with other guests, Mama between us. Suddenly I felt her stiffen, and I recognized Papa's cousin, Zebe Seaman, seating himself farther down the table. Uncle William rose to his feet as Zebe jumped up and came bearing down on us.

“Martha! What a delightful surprise. I had no idea you were coming home with William!”

At Zebe's friendly tone Mama relaxed. Rising and offering him her cheek to kiss, she said, “Zebe, what brings you to Albany?”

“The Legislative Assembly,” he replied. “I'm a member, and I have to come to meetings in this squalid town.”

Meanwhile I had risen and was standing by. Now he noticed me and stared hard. “Which son is this, Martha?”

At Mama's response, he gripped my hand. “My word, Ned, I'd never have known you. You have your father's breadth, but the look of the Jacksons still, don't you think, William? Now, let's find a spot where we can talk in private.

He ordered a table set up in a quiet corner. Talk we certainly did. Zebe wanted to know everything that happened to us since our flight from Schenectady. Mama was nearly through her recital when he suddenly interrupted her, his face serious.

“What's troubling you, Zebe,” she asked him.

“Gil Fonda. He may be at this very inn later tonight. He's a member of the assembly, too.”

Mama's face whitened, and I think mine must have as well. Uncle William rose to his feet in alarm. “We'd better find somewhere else to stay,” he said.

“I've a big room to myself here,” Zebe said. “I suggest all of you spend the night in it, and go to the sloop before dawn. That way he won't be likely to run into you in the public rooms or the hallways. Anyway, I shouldn't think he'd recognize Ned, or even you, Martha, after all this time. I'll sleep in the bed William and Ned have used.”

After we went to his room, Zebe had supper sent up, and we sat talking about the family. I listened more intently than when Uncle William had first arrived at Coleman's Corners, for I wanted to learn all I could about the people I would soon meet. About ten o'clock, Zebe excused himself.

Mama retired to the bed, which was in a dark alcove, and Uncle and I made do with armchairs. He soon dozed off, but I could not. A breath of fresh air might do the trick, but what if I bumped into Captain Fonda? The devil take him! As Cousin Zebe had said, I did look very different after more than two years. I refused to take fright at the mention of old Fonda. Out I went.

On my return, passing the tap room doorway, I spied Zebe, deep in conversation with the villain himself. So vivid was my memory that I had no difficulty recognizing Fonda even from behind. A flicker of doubt flitted through my mind. Could we really trust Zebe? I resolved to wake Mama and Uncle William well before anyone else was stirring and head for the sloop. I never closed my eyes, and when the tension was unbearable I roused the others, lit a lamp, and we closed up our carpet bags and Uncle's portmanteau. As we passed along the corridor, Zebe appeared.

“I was coming to wake you,” he whispered.

“Where's Captain Fonda?” I asked, half mistrusting him still. “I saw you talking with him last night.”

Zebe grinned at this accusation, every inch the plotter. “Blood is thicker than water, Ned. I slipped some laudanum into his whiskey, to make sure he'd sleep soundly.”

He escorted us through the town and down the steep bank to the wharf. Once aboard the sloop we thanked him for his kindness. He kissed Mama and shook our hands. “Godspeed,” he murmured. “I'll be home in a few days. Hope to see you then.”

We made good progress sailing down the Hudson River, and when we reached Manhattan we disembarked at King's Wharf. Uncle led us through the city of New York to a narrow brick house on Duke Street.

“I remember,” Mama said. “The Van Dusens live here.”

“They'll be happy to put us up for the night,” Uncle said.

Our hosts gave us rooms overlooking the garden at the back. We had a fine dinner and spent the evening chatting in an elegant drawing room. After a restful night we walked, baggage in hand, to the Long Island Ferry Dock. The oared ferry landed us in Brooklyn, where Uncle hired a chaise that took us barrelling along a smooth road towards Jericho. I gazed about me at a strange world that might have been mine, but for the fortunes of war.

“Everything's so civilized,” Mama said, sinking back on the cushions.

Without warning our driver drew up, and in the distance a horn tooted a long, flat note. Mama's eyes lit up. “The Brooklyn Hunt. We've stopped to let it pass by.”

A small red fox scampered across the road behind our rear wheels and vanished into the underbrush. On a hill the riders flashed into view, the hounds downslope in the lead. The pack scrambled through a pole fence, crossed the road and through a second fence. Noses to the ground they ran in confused circles round a pasture.

Thundering hooves shook the ground. Horses coughed and wheezed as men and women in high, round hats and scarlet coats jumped the fences and dashed over the grass. The hounds had scented something and were way out in front. I thought the fox was still in the underbrush. As we set off I saw him bolt back across the road, running away from the hunt.

“He's outfoxed them,” Mama said, chuckling. “The hounds are on a wild goose chase.”

“I wish Sam were here,” said I dryly. “He'd never believe this.”