Chapter 9

Two Homecomings

The soft, to my eyes dainty, countryside unfolded mile by mile. Not long after noon we stopped at an inn for food and a fresh horse. The day slipped by and the shadows lengthened. Against a red sky Mama pointed out a neat square brick house set in a grove of trees.

“Uncle Isaac and Aunt Phoebe Seaman live there,” she said. “Papa's brother and my sister. Their children, Jonathan, Caleb and Abigail, are your cousins twice over.”

“Because two sisters married two brothers?” I asked. “Yes, Papa grew up in that house. Isaac inherited it when your grandfather Seaman died.

“Will we see it in daylight, Mama?”

“I think Isaac will invite us.” She sounded uncertain. Was there bad blood between Papa and his brother?

Uncle gave the driver some instructions. Guided by lanterns on each side of the chaise, we approached a brightly lit square building somewhat larger than Uncle Isaac's. A black servant in livery hurried down the few steps and opened the chaise door.

“Good evening, Mr. William. Welcome home,” he said.

“Jason! How good it is to see you. Kindly give a hand to Mrs. Seaman,” Uncle said.

Jason handed Mama down, took our bags and followed the three of us into a wide hallway. As Mama was anxious to freshen up, with Jason we climbed a broad staircase and he led us to two large rooms. Each had a four poster bed with a canopy and a soft thick carpet. After he lit the lamps and pointed to fresh towels in Mama's room, he repeated the little ceremony in mine. I poured water from a flowered china pitcher into a matching basin, and removed the day's grime. Then I put on a clean shirt, tapped on Mama's door, and we descended the staircase side by side.

“Such splendour,” I observed. “No wonder Uncle was so shocked when he first saw our house.”

We joined Uncle in his drawing room until Jason announced that supper was ready Uncle gave Mama his arm for the walk to the dining room. Over a meal of hot roast mutton Mama and Uncle discussed the people she wanted to see. Their elder brother, Uncle Townsend Jackson was high on her list, but she spoke of her hope to see Uncle Isaac.

“I've sent Jason to Isaac's to tell him you're here,” Uncle said. “And my groom will take a note to Townsend in the morning.”

After the port, Uncle rose with a yawn. Mama could hardly wait to return to her room, and we two followed her to the staircase. Uncle led me to his room and selected two suits which I tried on. They were only a little large, and he told me to borrow both of them.

The sun was well up when voices below wakened me. My room faced the front of the house, and I beheld two saddled horses standing on the drive below. A groom was loosening the girth on one. My curiousity aroused, I dressed in one of Uncle's suits and hurried downstairs. Mama was seated in the drawing room with a strange man and a lad about my own age.

“Your Uncle Isaac and Cousin Caleb, Ned,” Mama said.

From the way she was smiling I knew that Uncle Isaac Seaman had come out of friendship. I thought he looked less like Papa than cousin Zebe, but Caleb reminded me of Cade. For a time the two of us stood awkwardly, listening to Mama and his father. To break the ice, I suggested we go outside and look around.

“Pity you weren't here yesterday,” Caleb said when we were by ourselves. “The Jericho Hunt met, and we bagged a brace though we had to dig for one.”

“Foxhunt,” I said. I had not the foggiest notion what he meant but I was not about to display ignorance, at least not yet.

“We meet again day after tomorrow,’ Caleb went on. “I know Uncle will lend you a horse. Won't you join us?”

I hesitated. If Sam heard I'd taken part in such an outlandish business I'd never hear the end of it.

“You do ride?” Caleb asked in a tone that implied I was some lower form of life.

“Of course,” I responded, nettled. Sam could go hang. I'd show Caleb I could ride as well as anyone on Long Island.

“I'll call for you at eight sharp,” he said. “Uncle usually rides, but I bet he'll stay home with your Mama.”

Uncle Isaac and Caleb left soon afterwards, and we had accepted an invitation to dine the next afternoon. Later, while we were still seated at our midday meal, we heard a coach rumble up the drive. The Townsend Jacksons had arrived—and like a clap of thunder. Uncle Townsend's wife, Aunt Mary, was kept hopping about by their ten lively children. I could not keep them straight, but the clamour and confusion reminded me of home.

Mama looked radiant surrounded by her near and dear. Any feeling of guilt I had over not being home to help with the work was put to rest. I was glad we had come, but oh, the muddle over names! Uncle Townsend had a Samuel, Stephen, Elizabeth, Sarah, and Margaret. I could not tell whether Mama was talking about his brood or ours in Canada.

“Thank goodness Uncle Isaac has only three children,” I remarked when the noisy visitors had left. “I won't have trouble keeping them straight tomorrow.”

In good time Uncle's carriage, driven by his groom, set out for the Isaac Seamans'. This time I could see the neat brick house clearly. Like Uncle William's the door was in the centre, flanked by pairs of windows. Fields lay on either side of the long drive, three horses in one, cattle and sheep in the other.

“Why didn't Papa learn farming when he was a boy?” I wondered.

“On Long Island many landowners employ managers and have slaves or hired men to work their land,” Mama explained. “They don't make their livings only from farming.”

I knew that my grandfather Seaman had owned the schooner Whitewings. Uncle Isaac, Mama said, had a store in Jericho, and was still operating the schooner. Uncle Townsend had two ships that crossed the Atlantic. Uncle William had fifty acres, Uncle Isaac sixty-five, and Uncle Townsend eighty. Amongst them they had less land than Papa but to me they lived like kings. I found Cousin Caleb good company, though in my mind his name belonged only to Papa. Caleb's sister Abigail, a bit younger, was a tease who reminded me of our Sarah. Twenty-year-old Jonathan had taken Whitewings to Boston, a disappointment to me. I longed to see the ship Papa had sailed in his youth.

“With more than 200 acres you must be very rich,” Caleb said. “How many labourers does Uncle Caleb keep?”

He looked incredulous when I replied, “None. We do our own work, and we're not wealthy. We'll be better off once we finish our raft and sell some of our timber.”

I described our wilderness acres and the raft on which our future depended, but he only half listened. Our worlds were poles apart. I did not go to school and would become a blacksmith. He went to a boarding school in Connecticut during the winter, and hoped to enter a law office. Yet I did not envy him. Long Island was too finished. My family had a new country to build. After the first excitement had worn off, I thought life on Long Island would seem very humdrum.

The morning of the hunt, Caleb clattered up the drive. As well as a horse, Uncle William loaned me boots and a scarlet coat. The tall round hat was a bit loose, but a strip of paper inside the sweat band made it secure. With my deerskin breeches I looked as though I belonged as we rode away. The riders gathered before a tavern in Jericho, where what Caleb called the master of foxhounds and the whippers-in waited with the hounds. The landlord brought cups of brandy, and astride our mounts we downed them, rather too fast for my liking.

We trotted out of the village, hounds capering in all directions, noses to the ground. Their baying started as they scented something. We picked up speed, jumped a gate and circled a field in single file. It was planted with grain and we were careful not to damage it. From a clump of bushes a fox broke cover. The frantic little thing leaped through a rail fence and sped over some pasture. The horses jumped one after another and the hunt spread out. The fox was out of luck. Before it could find somewhere to hide the dogs were tearing it to pieces. The whippers-in arrived too late to stop the destruction.

“Pity,” Caleb commented. “The mask and brush are ruined.”

“Eh?” I queried, nauseated by the sight of the dismembered fox.

Caleb's look suggested I was an utter dunce. “The face and tail. Trophies to give to the best rider of the day.”

We got three more foxes, making what Caleb called two braces. We walked the horses back to Jericho to cool them. At the tavern where the hunt had assembled, the master rode up.

“Did you enjoy your day, young man?” he enquired.

“Yes, sir.” I lied, but what else could I say without offending anyone?

The crowning humbug was still to come. Someone called my name, and Caleb took charge of my horse and pushed me forward. The master held up a tail, dried blood visible on one end.

“For our Canadian visitor,” he called loudly. “A fine rider.”

I accepted the grisly trophy. Caleb and some of his friends thumped my heartily on the back and I did my best to look pleased. Riding home, I resolved to make an excuse if I were asked to hunt again. Much as I loved a good gallop, the reason for this one repelled me. Instead I accompanied Mama when she wanted to ride. She sat a sidesaddle, a long riding skirt draped over breeches—both borrowed from Aunt Phoebe Seaman. One day, riding back from Uncle Townsend's, Mama looked at me in a strange way.

“I'd like to show you a house near here,” she said softly.

I did not need to ask who had once lived there. We turned off the main road and halted before a large white clapboard dwelling. Beside it stood a substantial stone building, great double doors open. Inside I saw several blacksmiths at work. I pointed to the stable yard visible beyond.

“Is that where the rebels seized Papa?”

She nodded. “Let's get away from here before I weep.”

I knew the rest. The rebels took Papa up the Hudson to a prison camp. When Mama heard where he was, she took Cade and Sam, mere babies at the time, and followed him. Papa escaped and they headed north. Eventually they settled in Schenectady and remained there until our flight to Canada. I felt haunted as we rode back to Uncle William's. The size of the shop had not eluded my eyes. Papa had sacrificed a lot for King George the Third.

The highlight of the visit, for me, came when Jonathan Seaman brought Whitewings into Oyster Bay and invited me aboard. Happily I climbed her rigging, but we hadn't time to sail in her. We had to get back to Uncle Isaac's, eight miles away, for supper. I liked Jonathan because he was very interested in my stories about the timber rafts, both the one we were building and Reuben's. The next day, back at Uncle William's, Cousin Zebe came to pay his respects. Before he left he gave me a letter for Papa.

“I'm sending him the names of the other Seamans who were Loyalists,” he explained. “A dozen families of our cousins are now in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. He may want to visit them.”

“Thanks, Cousin Zebe. I'm sure he'll be glad to know where they are.”

By the time we had been on Long Island three weeks, my conscience was really bothering me, and Mama was getting restless. When she told Uncle William we must leave, he had a bright idea. Why not go by sea? A ship of which he was part owner would be sailing for Halifax in a few days and we could have passage aboard. We would then have to pay only from Halifax to Quebec.

“Mama's jaw was set. “William, we'll pay all the way.”

“Fiddlesticks,” her brother countered. “If you won't let me do that much, I'll never come to Canada again to see you.”

“I'd love to go by sea,” I piped up, not wanting to miss the chance to sail on the Atlantic.

“Very well, and I'd better write to let Caleb know we're coming by sea,” Mama said.

“There's not much point,” Uncle replied. “You'll get home about as quickly as any letter even though you're taking the long way round.”

When the early August day arrived, Uncle William drove us to a tavern on the shore of Oyster Bay where all the relatives gathered to see us off. A schooner rode in the distance, sails flopping. While we watched, a ship's boat was lowered over her side and began moving towards us. We all trooped down to the shore as the oarsmen drew the boat upon the shingle. After kisses and handshakes all round, we stepped aboard. The crew put our baggage in and pushed off.

Mama waved, tears in her eyes, as we glided out into Oyster Bay. Suddenly I remembered! In these very waters the uncle whose name I bore had drowned. An eerie feeling swept over me that was broken by Mama.

“I'm sorry to leave, but longing to get back home to my dear family,” she said, dabbing at her eyes with a hankerchief.

My eyes were glued on the trim schooner whose great sides rose and fell, looming larger every minute. A sea voyage to Halifax! Another to Quebec! This would be a journey to brag about when we got to Coleman's Corners.

The name Annabel was painted on the schooner's hull. A rope ladder dangled down from the gunwale which a boatman caught and held steady for Mama. With considerable agility she gathered up her skirts and toe by toe climbed to waiting arms that hoisted her over the side. I followed, leaving the baggage to the crew, more experienced than I at climbing the flimsy, bouncing ladder.

Welcome aboard, Mrs. Seaman,” I heard a hearty voice boom above me. “Captain Josiah Clagett at your command.”

As I peered over the gunwale Mama was shaking hands with a burly man, weather beaten face partly hidden by a flowing beard. He did not look like the captain to me. He was dressed in the same garb as the crew—loose canvas trousers, woollen jacket and greasy pigtail at the nape of his neck. Captains of merchantmen, I decided, lived by less formal rules than officers in the Royal Navy. He led us down a companionway, his rather ordinary appearance outshone by a courtly manner. The port cabin, where we were to sleep, and his own to starboard, were the finest quarters on the ship, and he told us we would take our meals with him. Someone had hung a curtain between the two berths in our cabin, for privacy. Leaving Mama unpacking, I went back on deck, afraid of missing something.

Captain Clagett and a man he called Mr. Jukes were barking orders. Crew hauled up the sails. Out front on the schooner's jutting bowsprit were three small foresails, and aloft she carried topsails. The Annabel swung sideways as the wind billowed her canvas. We ran down the sound, flat Long Island to our right, the more rugged Connecticut coast on our left. The day was perfect, a fair breeze and strong sun.

A peep in the galley, reached by a companionway aft, revealed two bearded cooks, labouring before a brick oven with iron doors. An appetizing smell wafted from the small, cramped room. Beside it and below were the crew's quarters. That night we dined in the captain's cabin. A sailor served us, and our other company was Mr. Jukes, the ship's mate.

The voyage to Halifax was uneventful. August was a month when winds tended to be light and steady. When we went ashore the captain and mate came with us, for they had business to attend to. On firm ground I still felt the roll of the ship, and Captain Clagett was amused.

“”Still got your sea legs. That'll soon wear off.”

Halifax reminded me of Quebec, more for activity than appearance. Soldiers and sailors on and off duty were everywhere. Ships of the line, sails furled, rode at anchor in the huge harbour, and wharves lined the waterfront. Guided by Captain Clagett we found the harbour master, who knew which vessels were bound for Quebec. One, called La Mouette was about to sail.

“She's a fine brigantine,” Captain Clagett said. “Her master's Captain Pierre Kelly. Bit of a powder keg, being part Irish, but a good man for all that.”

He showed us a large hull with two tall masts and many yardarms. Captain Kelly spoke to us in French at first, but he switched to English at our blank looks. He had plenty of room, and he assigned Mama a cabin. Then he made me an offer I could not resist.

“Would you like to ship with me to Quebec, lad?”

“Wouldn't I just!” I replied eagerly.

“I'll refund half your passage money if you show you've a head for it.”

In a flash, deaf to Mama's objections, I began climbing the rope steps tied between two stays of the mainmast. At the topmost yardarm, tucking my toes into the safety ropes, I worked my way outwards and back again. When I looked down I felt dizzy, but the game was to look ahead. Gingerly I climbed back to the deck.

“You'll do,” Captain Kelly said approvingly.

Mama was not convinced. “We don't need to be that thrifty.”

“Please let me,” I begged her. “I'll never have a chance like this again And Papa was a sailor when he was young.”

“You won't let him do anything rash?” she asked the captain.

“Nothing I wouldn't do myself,” he replied.

I found setting the sails great fun as long as the breeze remained light, and the crew made good companions when I was off duty. In keeping with my humble station, I slept in a hammock below. The fun ended when, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence a storm blew up. Captain Kelly ordered us to reduce canvas before the pounding waves opened the timbers of the hull. With other crewmen I climbed the mainmast stays and crawled along the top yardarm to help furl a vast sail. What a job that was, fighting to gather up the sail without letting go the yardarm. Fortunately for Mama's peace of mind, she was feeling queasy and had gone to her cabin.

La Mouette put into Gaspé Bay to ride out the worst of the storm. At the head of the bay was a village and mail and passengers came out in a whaleboat. Back and forth we tacked against both wind and current. Our progress was so slow that we began to doubt the wisdom of returning by sea. The land journey would have been more tiring, but we might be nearly home by now. Not until mid-August did we make Quebec.

“How long before we reach Buell's Bay?” Mama enquired as the ship's boat was taking us ashore.

“Eight to ten days,” I confessed uneasily. “I'll go to the Upper Town as soon as we land and reserve seats on the next stage.”

We were in luck. Two seats were available first thing in the morning. We stayed at a hostelry in the Upper Town to avoid the long climb from the London Coffee House. At Montreal we had to wait two days before a brigade would be leaving for Kingston. We took lodgings at the inn we had used on our outward journey, and tried to be patient.

“Let's go to my room,” Mama said. “It's empty and we can count our money in private.”

We found, thanks to Uncle Williiam's generosity and to my working passage, we had four pounds left over. Mama decided to take advantage of Montreal's lower prices to buy things we badly needed. With a light step she led the way. We window shopped till she had made up her mind where she could get the best bargains. She chose needles, thread, sugar and tea, and two large bolts of heavy wollen cloth, enough to make winter coats for everyone. Her last purchase was on impulse. We were taking a walk towards the mountain when she spotted a tinsmith's shop. She halted, rubbing her cheek with a forefinger, making up her mind.

“I'll do it,” she said firmly. “I'm going to buy a tub. It's high time we had baths. Let's see if the smith has one for sale. If not, I'll order one and have it sent in a later brigade.

A customer had cancelled an order and the tinsmith had a tub on hand. We lugged the awkward thing to our lodgings. With our original baggage and the items we had bought, we were loaded down by the time the brigade was ready. After we carried the tub to the docks, Mama stood guard while I fetched the rest of our things from the inn.

When we reached Buell's Bay, I left Mama with the baggage and hurried home to fetch our cart, hoping a horse would be there. I found Sam, who had ridden in on the mare to catch up on orders for the shop. In jig time we were back at Buell's Bay.

“Oh, my,” Sam remarked as he heaved our tub aboard the cart. “We'll have to haul lots of water to fill this.”

Mama laughed. “If I recall, Samuel Seaman, you'd lie in a bath as long as I'd let you.”

At home, Mama began giving lots of cuddling to Smith, Sarah and Stephen to make up for the two months she had been away. Robert and Margaret, however, clung to Elizabeth. To Mama's sorrow they did not remember her at first.

We told our story that evening as we sat round the hearth, a small fire taking the chill out of the early September air. Brazenly I fetched the grisly brush and decided to present it to Sam.

“Where'd you get that?” he asked, holding it up and waving it about.

“Promise not to laugh?”

“What's funny about a fox's tail?” he snorted scornfully.

“You remember Uncle William telling you about foxhunting?”

“Ridiculous,” he scoffed.

“Gruesome's a better word,” I rejoined.

With that I described the hunt. Arms akimbo, Sam listened. When I finished he threw back his head and bellowed. “Well, I never,” was all he could say.

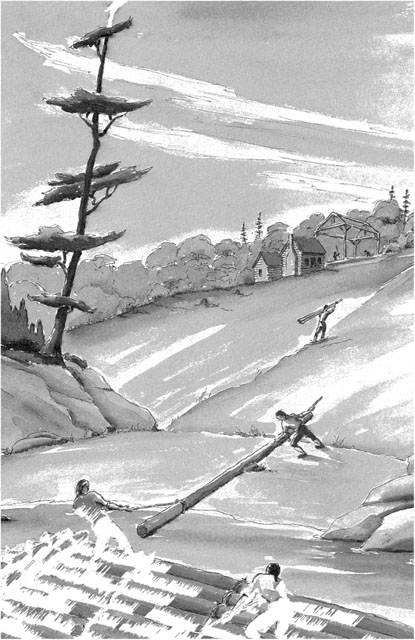

I helped Sam finish the ironwork, and we left together for our land, taking turns riding the mare, trailed by the twin fillies, now much grown. I could hardly believe my eyes when I beheld the great raft, though it was only half built. It floated in our bay, already almost as large as Reuben's. Cade and Papa, with the Mallorys, were tying another huge log that was floating loose, anchoring it with thick withies.

I hopped into the water at once and Papa had me pulling on a long willow strip to help tighten it till the log no longer shifted. Sam joined us as soon as he had rubbed down the mare and put feed out for her.

“Glad you're back, Ned,” Cade said. “And when it's dark you must give us a blow by blow description of your journey.”

“I'll like that,” said I. “And I know you will, too.”