Chapter 10

Finishing Touches

Not till after we had tied another withy did I notice a huge wooden framework standing close to the sheds Cade and Sam had built the autumn before. “What's that?” I enquired of Cade.

“The next stage in our farm,” he said. “We're going to have a barn before winter, so we can store enough feed. Papa wants to keep all the horses here after we come back from Quebec. Raising the frame was fun. Lots of neighbours arrived and so many hands made the job quick and easy.”

“We won't have time to finish it before we leave with the raft, will we?” I asked. “Surely it will take us weeks to do the walls, floor and roof.”

“They're well on the way,” Cade replied. “The logs for the walls are piled inside the frame, and Mr. Coleman will soon send the floor and roof boards and shingles. We expect to have the barn up and the raft ready to sail before the end of October.”

That evening we lit a great fire. “Now,” said Cade as we were making ourselves comfortable round it. “Ned, it's time to hear about this marvellous journey of yours.”

I did enjoy being the centre of attention. Sam actually listened as I explained, often with Papa's help, who was who. “Even after shopping in Montreal, we brought home two pounds ten left over,” I finished my story.

Papa looked at me accusingly. “You can't possibly have done such a trip and made your purchases on so little. Did Uncle William help out?”

“Only with the passage on the schooner,” I said hastily. “Mama felt she could accept that without embarrassing you.”

Then I remembered Cousin Zebe's letter and fetched it from my bag. Brows knitted, Papa read it, folded it and stuffed in his pocket. “I'm pleased to know where some of our cousins are, but Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are so far away. I'll never have a reason to visit any of them.”

“Now that you've seen the place we came from, where would you rather live, Ned?” enquired Cade.

“Oh, here, of course,” I said stoutly. “I loved Long Island. But seeing how people live in an old settled place made me appreciate what we've built here. And we've really only begun.”

“Didn't you envy the relatives their wealth?” he asked. “Those fine houses?”

I was watching Papa as I replied. “No, I didn't. Their lives are different, but ours are just as good.”

“What did you make of your Uncle Isaac?” Papa asked me.

“He was polite, but I really did not talk with him much.”

Papa laughed to himself. “I guess he was feeling ill at ease. He used to be very proud that he was a drummer boy at Quebec under General Wolfe.”

“Was he indeed?” Cade interrupted. “Then you're two of a kind, Papa. Look how long you took over telling us about our past, our roots?”

“Now,” said I. “Tell me all your news.”

“We were here when Governor and Mrs. Simcoe passed by soon after you left with Uncle William,” Cade began. “They stopped in Kingston, and some people from here went to see them.”

“We saw Mrs. Simcoe, too,” I said. “Is Kingston our capital?”

“No, he went on to Niagara and called an election.” This came from Papa, which did not surprise me.

“I guess it's as well Mama missed that,” I said, though I was sorry I had. “Were there many fights?”

“None at all,” Papa admitted. We did not have a contest in our riding. Governor Simcoe had Mr. John White, the attorney general, run here. Mr. White is an Englishman who arrived in the spring. We thought we should not run anyone against a man the governor had chosen. We've some new names, though. The governor set up counties. Ours is Leeds. The one to the east, where the Sherwoods live, is Grenville. This township has been named Yonge.”

“Who decided on the names?” I was disappointed that our name would never grace the township.

“Governor Simcoe. He's calling all the townships after his friends, and the counties after British ministers,” Papa finished.

“What do people think of him, I wonder?” Sam asked.

Papa sighed. “The Yankees are saying the assembly that's to meet at Niagara later this month has no power. We'll have to wait and see what happens.”

“Meanwhile, we've too much to do here to worry about the government way off at Niagara,” Cade said. “Goodnight all. I'm off to bed.”

“Me, too,” Papa said, getting to his feet. “I want to take the bateau to Buell's Bay and go home for a quick reunion with Mama. I can't stay long, of course.”

We were all up early. By the time Papa left, we were levering another huge log into the water. Later in the day Jeremiah and Elisha Mallory arrived. The work on their own farm was caught up and they had time to help us again. We were adding a second layer of logs to the raft by that time, laying each log crosswise over the lower logs. The bottom layer was of white pine, but some of the logs in the upper one were of oak.

“Oak is heavy and floats so low that the surface of the raft would always be wet,” Cade explained to me. “Pine's lighter and will make the raft float higher in the water so we'll stay dry.”

“Reuben's raft was only one layer,” I recalled. “But all his logs were white pine.”

Later, Captain Sherwood rode in with Levius. They were on their way to Kingston, where Levius would stay for school. Samuel had had enough education, and would be helping his father with the survey work and the timber rafts.

“Lucky Samuel,” commented Levius.

When he saw Captain Sherwood, Cade came hurrying from the raft. “We could use some advice, sir, and our father will be at Coleman's Corners till tomorrow at least. We need a sailmaker and hope you know where the nearest one is to be found.”

“I have a man at Kingston,” the captain replied. “Would you like me to order a sail, made from the pattern he used for mine?”

“Please do, sir,” Cade said. “I have some cash here. Should I send it with you?”

“No, just write me a note. Once we know how much the sail will cost, you can arrange payment.”

When Papa returned the next day, he had Mama, Robert and Margaret with him. “I've come to give you decent meals and to watch the autumn colours,” Mama greeted us. “And I couldn't bear to think of the raft going without seeing it for myself.”

A few days later we postponed work on the raft in order to finish the barn. With six nearly grown men all helping we did not take long to pile log on log for the walls. Before we had the walls up, Captain Meyers arrived in his Durham boat. I seemed to be the only one who did not know why he had come when Papa called us to join him beside the boat.

“The boards from Coleman's mill,” Cade explained as we were running to the shore.” Mr. Coleman sent them to Buell's Bay by wagon, and Captain Meyers brought them along the river for us.”

His son Jacob was with him. “Hallo, Ned,” he greeted me. “That Yorker captain hasn't caught up with you yet, I see.”

I had to think a moment before I realized he meant Captain Fonda. Then I decided to make a good story out of our near encounter. “He came close in Albany a few weeks back. Staying at the same inn, but we eluded him.”

“What!” Papa exclaimed sharply. “You didn't say anything to me, nor did your mother. You mean you actually saw Gilbert Fonda?”

“It wasn't important, for nothing happened,” said I lamely, wishing I had not bragged to Jacob. Then I told them about Zebe putting the potion in old Fonda's drink, and about our stealing away at dead of night.

We unloaded the Durham boat and the Meyers left for the Bay of Quinte. In a surprisingly short time the barn was up. Cade and I then worked on stalls for the five horses—the stallion, mare, yearling colt and the twin fillies—and on feed bins. Hay had been drying in stacks and we carted it in and pitched it into the loft we had floored.

Mama, meanwhile, was making the cabin more comfortable between preparing enormous meals and sewing heavy coats from the cloth she had bought in Montreal. When she had a few moments, she sat on the great rock that extended from our shore, the one where we liked to dive, gazing out at the islands. They did look a picture. The reds of the maples were as bright this season as last. The sky was usually a vivid blue, with small wisps of white cloud, and none of us ever tired of the scene. An added attraction was the occasional ship that we could see passing above the western end of Grenadier Island. Some were merchantmen, but most were government ships of the Provincial Marine.

We really appreciated Mama's meals. The colder the days grew the more we seemed to need to eat. Wading in the St. Lawrence was becoming a very chilling business, and we were desperate to put the few remaining logs in place. At last the job was done, and Papa was satisfied that we had bound the logs with enough withies for the journey down the rapids. Next, we had to erect a cabin like the one that had protected us on Reuben Sherwood's raft, and the mast.

We chose a slender, straight white pine for the mast, and stripped it. Then Papa took charge of raising it. Though I had walked over the logs many times, I had not noticed the square hole, smaller than the bottom of the mast, in the centre of the raft. It had been left when the logs were being placed. Nor did I see the importance of wooden cleats on the front and on each side of the raft. Before we tried to lift it, Papa had Sam and me shave around the bottom end of the mast to make it fit into the hole. The thicker part above would keep it from slipping down.

Next came a halyard—the rope we rigged to raise and lower the sail. Papa was most particular over that. He fussed with the rope and a wooden pulley he had made, watching it slip smoothly along the length of the mast.

“If the sail should jam and not drop at the rapids, we could lose control of the raft,” he said when we were growing impatient. “This has to work perfectly.”

Next, he attached the forward and side stays a third of the way from the top. Once he was satisfied that the halyard was running smoothly, we had to step the mast, and that was tricky, too. With all of us holding it along its length, Papa had us direct the bottom of the mast into the hole in the raft. Then we walked it up as high as we could reach. Papa took hold of the forward stay and pulled, calling on Sam and the Mallorys to help him. The tall pole rose steadily until it was almost at right angles to the surface of the raft.

“Hold it right there,” Papa shouted. “Ned, come here and help hold the stay till I look at the angle.”

He wanted the mast tipped backwards slightly, raked, he called it. That way the sail would pull better. He had Cade and the Mallorys fasten the side stays first, then several of us held the forward stay steady while Papa fastened it to the front cleat and wound the rope securely. Again, with the mast up, he slid the halyard up and down.

“Now,” he said. “All we need is the sail.”

He decided to take our bateau to Kingston to pick up the sail Captain Sherwood had ordered. It would be bulky, and with no decent road he could not use a cart. I would love to have gone along but I was not disappointed when Papa chose Cade to help him in the bateau. After all, the others had borne the brunt of the work for most of the summer. While they were gone, Sam and I worked on the raft's cabin, and with the Mallorys' help it was nearly ready when Papa and Cade came floating back from Kingston three days later.

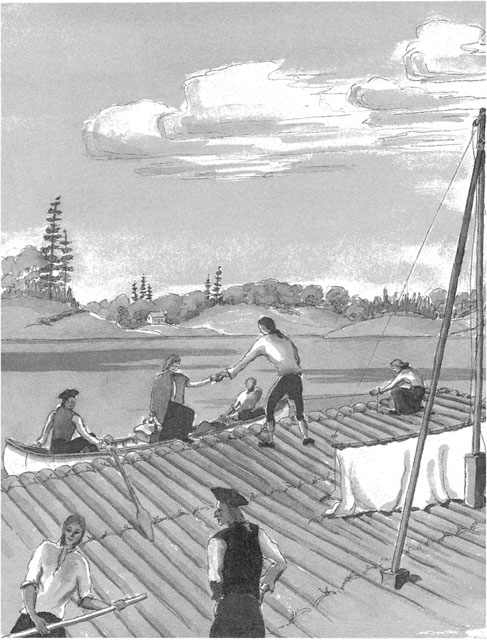

We helped them spread out the huge lateen sail on a patch of grass. A slim yardarm was lashed along the top of the canvas. Papa examined the sail for a time before he figured out just how to raise it. Then we folded it carefully, moved it onto the raft, and unfolded it. Papa attached the halyard to the middle of the yardarm, and Cade and I hauled while Sam and he kept the sail from twisting about. Up the sail went without a hitch, and Papa showed us how to cleat the halyard tightly.

Mama came aboard to admire it. “You haven't lost the knack, Caleb,” she said to Papa.

“Wait till I see how it comes down,” he cautioned her. “Uncleat the halyard, Ned. Now, very gently.”

We strained against the line, letting out a little at a time. The sail descended to the surface of the raft as smoothly as it had on Reuben's. Papa was still not satisfied though. “Hoist it again!” Before we could cleat it, he shouted, “Now I want to see how it would work in a crisis. All let go now!”

We obeyed and the sail fell down, the yardarm making a bang as it struck the logs. Papa brushed an arm over his forehead. “I think we can trust that. If the wind pushes you where you don't want to go, at an island, for instance, you must be able to down sail in a flash. Even then a heavy raft will keep moving for some time, but we don't want the sail helping it along.”

Sam and I were used to keeping our feet on a raft, after being with Reuben, but Cade and the Mallorys needed practice. Elisha and Jeremiah had cowhide boots, which tended to slip more than our moccasins. Mama got busy and made pairs for them, sewing them with thongs as we sat by our fire after supper. One night she put down her work and was looking sad.”

“Penny for your thoughts, Martha,” Papa said.

“I'm thinking about Elizabeth, back at the house, taking care of things there. I wish she could have a break as I did.”

I thought she was giving me the opening I needed. “Could she come with us to Quebec City on the raft?”

“Would you allow her?” Papa asked Mama. “She would be as safe as any of us.”

Mama smiled. “I think that's a wonderful idea.”

“You'd be on your own, with the five youngest,” Papa said, looking doubtful. “Smith's still only eight. He tries hard, but he's not very big.”

“I could have one of the McNish girls come and spend the nights with me. I don't mind being alone with the children during the day. I'm not nervous about the nights either, but I would like company in case anyone takes ill.”

“Then that's settled,” said Papa. “As long as Elizabeth wants to come.”

“She'll jump at the chance!” I said confidently. I knew my sister better than anyone else. “I'd like to see her face when you tell her.”

“You will,” Papa said. “You and Cade may take Mama home in the bateau and bring Elizabeth back. I want to send some grain to Coleman's Corners for winter feed, and to be ground into cornmeal and flour.”

Before we were ready to leave, our friend Mr. Truelove Butler came by in his canoe, as he had promised when he saw us with Reuben. I had first met him when we were arrested in Schenectady, and Papa and I found him in the jail cell where we had been confined. As soon as I recognised our old friend, I ran to the beach and helped him lift the delicate craft from the water. While we walked towards our stubble fields, the rest of the family gathered, Mama in the lead.

“How nice to see you again, Truelove,” she said, extending a hand.

“I've wanted to come for months, but I had to wait till my autumn work was finished,” he said. Then he pointed to our raft. “I've heard about that, Caleb, and decided I had to see it close up.”

“I pray it's sturdy enough,” Papa said. “Tell me what you think.”

Everyone trooped to the raft and got aboard. Mr. Butler seemed most impressed. Papa had us hoist and lower the sail, which we did without tangling anything. Our guest invited us to have a meal at his farm while we were on our way downriver, but Papa declined.

“I'm sorry, but I am afraid to stop just there. The river's very straight and the current is strong. The only way to slow these rafts down is by steering out of the channel and into a quiet bay.”

That surprised me. I could not recall that Reuben had trouble stopping the raft. Then I thought again, and realized Papa was right. Reuben had chosen spots where the current was weaker than in the main channel.

Mr. Butler stayed the night, and he set off in his canoe just before Cade and 1 left in the bateau with Mama, Robert and Margaret. The southwest wind was blowing briskly, which gave promise of a fast run to Buell's Bay. Cade kept the canvas straight while I pulled on the halyard and our sail slipped up the mast. Margaret and Robert were happy, trotting along the floor, Mama keeping a watchful eye in case they got too close to the gunwales. In four hours we were at Mr. Buell's and Mama was picking up a few things she needed.

“My hired boy will drive you to Coleman's, Mrs. Seaman,” Mr Buell told Mama. “I hear the only horse at your place is the colt. How is the raft coming along?”

“It's ready to sail, Mr. Buell. I expect it will be leaving Yonge Township as soon as Cade and Ned return there. And thank you for your kind offer. I'd be most grateful for the drive home.”

Needless to say, Elizabeth was delighted when Mama told her she could come with us if she liked. “I never hoped to see Montreal or Quebec,” she fairly shouted, dancing about.

She went off to the McNishes almost before we were in the house, and returned with the promise that Hannah, the eldest girl, would come the next evening and stay as long as Mama wanted her. Elizabeth showed us the cloak she had made from the green velvet Uncle William had brought. It was lined with squirrel skins for extra warmth.

“I'm glad I thought of the fur,” she said. “It will be perfect for late autumn.”

“You can't wear that on the raft,” said I. “You'd ruin it.”

“For the raft and the brigade,” Mama said. “I think a pair of Ned's outgrown breeches I've saved for Smith, and one of the coats I've been making. But you should pack the cloak and your good muslin dress to wear at inns and the one you're wearing for the stage coming home. And I'll send the cloth Uncle gave Papa so he can have a suit made in Montreal.”

“We'll have quite a lot to carry,” Elizabeth said. “Dave'll be happy to drive us in his cart, I know.”

I felt that usual stab of jealousy, but I turned to practical matters. “What'll we do about the dog?”

“Goggie will stay here,” Mama said. “He's such a good watch-dog.”

“You'll have to keep him tied all the time we're gone,” I said. “Or he'll go looking for Elizabeth.”

“I should have thought of that myself,” Elizabeth sounded so sad. “We'd still have Goliath if I hadn't left him to go on the raft we made while on our journey from Schenectady.”

Goliath was the furry beast who had got lost in the forest and was never seen again. Elizabeth adored him, but I had thought him rather stupid. When we decided to move our belongings on a raft, Elizabeth, Cade, Sam and I went with Mr. Butler. Papa and Mama and the four youngest went with the horses, and Goliath. When he disappeared we believed he had gone in search of my sister. Personally, I much preferred Goggie, who was more intelligent than Goliath.

As Elizabeth expected, Dave Shipman drove us to Buell's Bay. We carried the extra warm clothes, some food for the raft, and blankets. Behind us Goggie, tied up outside the house, howled in misery. I did not know whether I was sorrier for the dog or for Elizabeth, who soon covered her ears and shut her eyes.

We had not finished loading the bateau before we heard Dave's dismayed, “Oh, no!”

A delighted Goggie came galloping from behind Buell's store, a length of rope dangling from his deerskin collar. “Didn't take you long to chew through that, did it, boy?” said I. “Now what'll we do? He'd be a nuisance on the raft, and I don't think dogs are allowed on the stages.”

“I'll take him home with me,” Dave said.

What a hope! Visions of Goggie meeting us downstream filled my head. Fortunately I had misjudged my sister, the dog, and Dave. As Goggie sat quivering in the bateau, Elizabeth raised an arm and pointed to where Dave was standing on the jetty.

“Go with him, Gog,” she commanded sternly.

Tail drooping, he looked as though he had lost his last friend. She glared and repeated the order. Slowly, head bowed, he hopped on the jetty and pattered to Dave's side. “Good fellow,” Dave praised him, rubbing his head. “Come along.”

As Dave climbed into his cart, the dog followed him. We hoisted the bateau sail and Elizabeth and I each used a pair of oars till we had cleared the bay. The wind was from the northeast this morning, which meant sailing rather than rowing. It was also bitterly cold, and I sat hunched under a blanket at the rudder while Cade manned the sheets.

“Happy?” I asked Elizabeth.

“What do you think?” she replied, sighing deeply.