Chapter 11

Our Great Raft

Sam was standing on the raft when we arrived in the bateau. “You'll never guess what,” was his greeting.

“I don't care much for guessing games,” Cade said. “What's the matter?”

Still Sam teased. “Come and look. Something's missing.”

The three of us furled the sail and secured the bateau before joining him on the raft. Cade and I could not find anything amiss. I suppose that was because we had looked at the raft so often. Elizabeth, though, was seeing it with different eyes.

“Don't you need a rudder?” she enquired.

Cade clutched the sides of his head and groaned. “How on earth could we have overlooked that?”

We found Papa outside the barn, patting one of the fillies while deep in conversation with Elisha Mallory. I assumed he was making last-minute plans, for Elisha was to stay and look after our farm while Jeremiah accompanied us on the raft. Papa glanced up at our approach, and his face seemed troubled. When we explained about the rudder he looked grave for a moment, then he saw the funny side.

“We'd have discovered that pretty quickly if we had prepared to sail,” he said. “But Elisha has sad news.”

“I was just telling Mr. Seaman that Pa's had a fall and won't be able to do our work for a while. Jeremiah's needed at home and can't go with you as crew.”

“The rest of us can manage the raft,” I spoke up. “Elizabeth can handle mooring lines as well as any of us. The only time we'll miss Jeremiah is when we have to take the raft apart in Quebec. That's pretty heavy work for anyone.”

“Surely I can help in some way,” Elizabeth said.

“We put fifty logs from our farm into the raft,” Elisha continued. “Pa says you should give us cash for forty, and the other ten will be payment for delivering them at Quebec.”

Papa shook his head. “That's far too much. We'll pay you for all fifty. I'll not profit from another's ill luck.”

“Whatever you say, Mr. Seaman. We want to be fair.”

“Then that's settled,” said Papa. “Now for the rudder and then we can get under way.”

That did not take long. We had plenty of boards lying about and we soon fashioned the long, oarlike arm, the blade good and wide. We built a bracket on the back of the raft to hold it, and Papa practiced sweeping it back and forth to make certain it worked properly. Then he checked the halyard and had us raise and lower the sail yet again. By now those motions were second nature to us, which was what he wanted. At last he was satisfied. He inspected the baskets of food stowed in the cabin—smoked hams, dried apples, eggs, cheese, lots of potatoes and carrots, and flour from which we could make pancakes. With the fish we could catch, we would be well fed for most of the journey.

There was not much breeze, but it was from the southwest, and the sail filled as soon as we hoisted it. Sam was at the rudder as we loosened the mooring lines. Elizabeth watched intently as the cumbersome raft began to move. She caught a line I tossed her and began coiling it neatly as I jumped aboard. The unfamiliar part, for me, was the first few miles. We had to move out into main channel, the one the ships used, once we were below Grenadier Island. There were many shoals close to the north shore which would spell disaster if we grounded on any of them.

When we were above the Narrows we steered across the river almost to the north shore. The main channel now lay north of the islands of the Narrows, close to the Canadian shore. We took turns steering, as Papa kept watch for patches of dark or rough water that warned of shoals. At this point there were many, lying close to both sides of the main channel.

About a mile below Buell's Bay, a canoe approached us and we recognized Mr. Butler in the rear. A young lad was paddling in the bow, and a woman rested her back against the centre thwart.

“We've brought a picnic,” Mr. Butler called out. “Since you're worried about tying up here.”

“What a delightful surprise,” Papa called back. “Welcome aboard!”

Elizabeth caught the line the boy in the bow threw, and I took Mr. Butler's hand to draw the stern parallel with the side of the raft. In a trice we had tied both ends of the canoe, and the introductions began.

“My son Truelove,” Mr. Butler said as the boy hopped out. “My wife Mrs. Butler.”

“Very nice to meet you at last, Mrs. Butler,” Papa said as he took her hand and helped her out of the tippy canoe.

I thought Truelove Junior resembled his father, the same sturdy build. Mrs. Butler was pleasant-looking with pink cheeks and brown curls round her face. Her gown and cloak were of homespun and a straw bonnet covered her mob cap. Mr. Butler handed up two baskets. It was mid-afternoon and we were well and truly ready to dine. The Butlers spread out blankets, and on top of them a glistening white table cloth. From the baskets came cold chicken, slices of freshly baked, buttered bread, preserved strawberries in thick, sweet syrup, carrot pudding and flagons of cider. By this time we were passing Captain Sherwood's farm.

“I guess he's already left with his latest raft,” Mr. Butler observed. “It was nearly finished the last time I was down here.”

In no time all the food was gone. We chatted for a bit and I told Mr. Butler about taking Mama to Long Island and about seeing Captain Fonda in Albany. He whistled over that, and told me he had finally been sent the money from his late father's estate. That was the reason why he had gone back into New York State, when he had been recognized as a Loyalist and found himself in the Schenectady jail.

He rose to his feet. “We'd better not linger,” he said. “We'll be paddling against the current, and must get home for evening chores.”

“We certainly appreciate such kindness,” Papa said as he bowed over Mrs. Butler's hand and kissed it. “Your meal was delicious.”

After we waved them off in their canoe, we lowered sail for the ride down the Galop Rapids and left it down until we had passed Rapide Plat. I watched Elizabeth as the raft surged forward, and she seemed to be enjoying the motion. Cade, Sam and I moved about, inspecting the withies, but all of them held firm. Papa was at the rudder at the time. Afterwards we looked out for a good place to stop for the night, and he soon steered into quiet waters. We caught plenty of fresh bass, built a fire on shore, and feasted.

“After everything we ate this afternoon, how can we be this hungry so soon?” Elizabeth remarked.

As the night was fine, most of us slept wrapped in blankets near the fire. Papa stayed aboard the raft so that if it broke loose he would know to rouse us. We next tied up at the spot above the Long Sault Rapids where Reuben had stopped the autumn before. It was only mid-afternoon and we kept watching for the Mohawk pilots. They came in their canoes before nightfall, and slept round our fire, ready to build their crib at first light.

Papa, Sam and I knew what lay ahead, while Cade and Elizabeth had questioning looks on their faces. We gave everyone breakfast—more fresh fish, slices of ham and cakes made of eggs, flour and water which we fried in one of our pans. Elizabeth made tea, which the Mohawks seemed to relish. Then we got to work on the crib. Papa, Cade and Sam helped cut the eight logs. Elizabeth and I went in quest of the willow strips to bind it. We severed them with the knife Uncle William had given Cade, and returned with our arms laden down. One of the Mohawks gave Elizabeth a wondering look.

“Aren't you a woman?” he asked.

She laughed as she nodded. “Petticoats don't go with rafts.”

“Well, you don't need to be afraid when we go down the rapids,” he continued. “We're very good pilots and always bring the rafts through in one piece.”

“I know I won't be afraid,” she responded.

Again the Mohawks stationed themselves along the rapids, and again we released the crib. Again we waited a long time before the Mohawks were all back and aboard the raft. The roar of the water soon drowned out everything but the shouts of the pilots as they changed places at the rudder and used their poles. I watched Cade and Elizabeth while hanging on with everything I possessed. Even this second time I was terrified, and I felt faint when the last pilot was steering for shore.

On the bank a very pale Cade swayed and dropped the mooring line I threw him. Elizabeth seemed wobbly, but so did Sam. Once we had tied up, we thanked the Mohawks, this time with Papa in the lead, shaking each man's hand and giving him some coins.

“Will we see you next year, sir?” one of them asked.

“Maybe,” Papa rejoined. “But I think in two years is more likely.”

“You may see Captain Sherwood at Quebec,” another informed us. “He's only two days ahead of you.”

Before we untied, Papa had us inspect the withies again, and he was not satisfied with some of them. We spent the rest of the day bringing in more of the willow strips and binding some of the logs more tightly. The Long Sault Rapids were the worst, but Papa did not want to take any risks. We still had to tackle the white waters at the Cedars and Cascades and at Lachine.

We had rain as we floated along Lake St. Francis below Pointe au Baudet, at the boundary between Upper and Lower Canada. We tied up to trees and spent a night in the cabin because the land was so wet. At the Cedars Rapids, Indians built another crib and guided the raft as before, until we had descended the Cascades.

“This is Lake St. Louis,” I told Elizabeth as the shores became more distant. Montreal's not far ahead now.”

“I'm looking forward to landing there,” she said.

“That won't be until we're on our way home,” I told her.

“What a good time we'll have on this visit. With pots of money to spend,” Sam gloated, rubbing his hands together.

“Let's not think about that till we have the money in hand,” Papa cautioned. “Isn't there a saying, ‘don't sell the bear's skin till you've killed it’?”

We had no difficulty with the Lachine Rapids. After the Indian pilots left the raft, Papa again had us check the bindings carefully to make certain everything was still strong. Again we added more withies. This was freezing cold work now, as the temperature of both air and water was very low. We found we needed all the heavy clothing we had brought.

For me, the most alarming part of the voyage began when we were off Sorel. We were heading for the stretch of slightly fast water called the Richelieu Rapids. The breeze was from the northeast, but I knew the raft would float down the rapids. Our problem was finding our way through the flat islands. Even with Reuben's list of landmarks we had trouble finding the right channel. My own fears were confirmed when Papa began to look ever more worried. The opening through the maze of islands kept eluding us, yet we were drawing ever closer to them.

“If we ground on a sandbar, we'll be in real trouble,” Papa said.

We were moving only with the current that day. Our sail was of no use when the breeze was against us, for it only worked when it was behind us, pushing the raft. Unlike the topsails on a schooner, our lateen sail could not carry us into the wind. At last we thought we were saved when we spotted a white sail coming from between what must have been two islands. Until that moment we thought we had been looking at the unbroken shoreline of just one island.

“That's the right opening,” Sam cried. “I remember now.”

“It has to be, since the sailing vessels are able to come though it upstream,” Papa agreed.

We moved forward slowly, and found other ships coming towards us into the channel. The wind was blowing in our faces, but for the ships it was behind them, pushing them upstream. Papa looked more and more worried as we slipped downstream. Our raft was unwieldy and might easily collide with an upbound vessel. We all felt very tense as some schooners kept running towards us. To give their helmsmen credit, they were trying to avoid us while making their way against the current.

“Pray we get through this without crashing into any vessels, or running aground while trying to avoid them,” Papa said.

“Amen to that,” Cade murmured. “I don't like this at all.”

My teeth were chattering, not so much from cold as fear. Our raft was now picking up speed as it descended, while the ships had almost stopped moving forward. The breeze had suddenly shifted to the south, which did not affect the raft but it left the ships almost becalmed. Papa really showed his skill as a sailor, and left me bursting with pride. He could not manoeuvre the raft about, but he was able to shout advice to upbound helmsmen, which helped them keep out of our path. At last, we were well below the islands where the ships had more room to avoid us.

“The next time, we'll wait for a southwest wind even if we're delayed as much as a whole week,” Papa said. “That way, fewer ships will be trying to come upstream.”

The worst danger was past, but not the end of hardship. On Lake St. Pierre a storm threatened and we steered for shore and tied up. There we remained for three days, watching the huge waves moving eastwards downstream. We constantly checked our mooring lines and added extra ones to make certain the raft would not break loose and rush away in such high winds. Otherwise we huddled in the cabin, longing for a roaring fire on shore. With everything so soggy from the rain, and in such winds, we doubted we could start a fire or keep it going if we succeeded. How we avoided catching cold I'll never know. We tried to pass the time telling one another stories, but we had not the heart for them.

When the winds finally dropped and the sun shone, we spread clothing and blankets out to dry round a fire. The dampness had penetrated everything we owned. Afterwards we set out again, the breeze light so that our progress was slow. I thought we would never reach Three Rivers, at the foot of the lake. When we finally did we brought the raft in beside a wharf. Papa left we three boys to guard it, and he told Elizabeth she could come ashore with him.

“I want to order some iron to be sent with the first brigade that has space for it,” he said. “I hope it will be waiting for us at Buell's Bay when we return.”

Once we had left Three Rivers, the waterway narrowed and we were again in the St. Lawrence. Most of the rest of the journey was smooth sailing, except for two days when we were almost stopped by a northeast wind blowing straight up the river at us. By mid-November we were watching for Wolfe's Cove, gliding below the high cliffs. The air was colder than ever, for rock walls blocked out the sun, leaving the raft constantly in the shade. Yet we were all in good spirits, happy to be so close to the end of our voyage. With a sense of relief we glowed at the thought that we had brought the raft safely to our destination.

“Now we're nearly there, Papa, I keep remembering what you told me about Uncle Isaac,” I said.

“About his having been here with General Wolfe?” Papa asked. “As a drummer boy?”

That was news to Sam and he pricked up his ears. “Which regiment was he with, Papa?”

“The 60th,” Papa answered. “It was raised in the colonies.”

“How old was he?” Cade enquired.

“Fourteen,” Papa replied. “He ran away and enlisted. Your grandfather was not pleased with him over that.”

“Where were you at the time, Papa?” Sam wanted to know.

“I was nineteen then, and starting my business and also serving in the militia.”

“No wonder I long to be a soldier,” Sam said. “It's in my blood.”

“If we're so close, why can't we see the city?” Elizabeth repeated what I had said the year before when I first saw Wolfe's Cove.

“It's about to burst upon you,” said I.

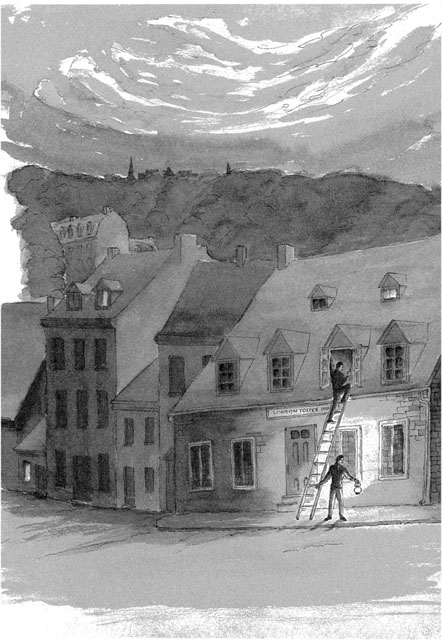

Even the second time, when the raft rounded the bend and the harbour of Quebec appeared as if by magic, I was still taken by surprise. There were the tall spars of the Royal Navy vessels, the smaller merchantmen and the many bateaux. I could see the red tiled roof of the London Coffee House as I searched for space at a wharf where we might tie up. The sky was grey and to me Quebec was not looking its best.

“Beautiful!” Elizabeth exclaimed. “I've never seen anything like this. Even on such a dull day it's splendid.”

“There's a likely spot to moor,” Sam said, pointing.

“You're right,” said Papa, who was steering at the time. “Down sail. Quick!” Once we had obeyed, he explained. “We've just enough way so that we won't stop before we reach the wharf. And we're not going fast enough to crash into it.”

From up front Sam yelled, “Do you see that shallop?”

I ran forward, and before I could spot it Sam was shouting and waving his arms. “Tack! Tack!” he fairly screamed. “Get out of our way!”

Now I had a clear view and I joined in, waving my arms and shouting. The tiny craft brushed against the side of the raft before its sail swung over and it proceeded on the other tack.

“What a close call!” I cried, sweat on my face despite the cold.

“I'll say,” Papa admitted, pale and shaken. “You'd think, anyone sailing in this harbour would have a healthy respect for a timber raft. Whoever he is, he's lucky to be still afloat!”

We brought the raft safely to the wharf, and Elizabeth and I were the first to hop out. Cade and Sam threw us lines and we found iron cleats to which we attached them, wrapping the rope round and round. Once we had finished, and the others had joined us, we counted three other rafts moored farther along the wharf.

One was deserted. The crews aboard the other two rafts sported fringed hunting shirts and buckskin leggings. Some of the men in our settlement dressed that way, but it was more common among American frontiersmen.

“Where do you think they come from?” I asked Papa.

“Somewhere along Lake Champlain, perhaps,” he replied. “Men from Vermont and northern New York bring timber to sell at Quebec, because the streams from there all lead to the St. Lawrence.”

“And rafts don't float upstream very well,” Sam added.

“Any dunce knows that,” I snapped. I had been cold long enough on the raft and was in no mood for Sam's humour.

“That will do,” Papa said sternly.

Now Cade changed the subject. Touching my arm he pointed toward the steps of the London Coffee House. “The Sherwoods. The empty raft must be theirs.”

With Captain Sherwood were Samuel, Reuben and the slave Scipio. As I was about to wave to them, a shouted order from one of the occupied rafts chilled me to the marrow, if I could have become any colder. My eyes were drawn back towards that sound. The dress was unfamiliar, but the set of the shoulders was unmistakable. My last glimpse of them had been through the taproom door of that inn last July in Albany. The man in the frontier garb shouted another command and I could sense Papa's eyes upon him.

Shivering, I whispered,” Captain Fonda!”

“Who?” Sam demanded loudly.

“Hush!” Papa commanded. “Ned's right. Don't attract any attention, Sam.”

“Well, who is he?” Sam repeated, softly this time.

“Captain Gilbert Fonda,” I hissed. “We'd better make ourselves scarce.”