Determining the Gender of Masculine Nouns

Determining the Gender of Masculine Nouns 03 / Grammar

Intro to Grammar

English and German are Germanic languages and are derived from the same Indo-European source. It is that legacy of language that still exists in modern English that makes learning German a relatively easy task.

Understanding Gender

In the English language, “gender” refers to the sex of living things: Males are of the masculine gender and females are of the feminine gender. Inanimate objects are called neuter. German is a bit different.

The German Concept of Gender:

In general, German looks at words that represent males as masculine and words that represent females as feminine. But gender is not entirely based on sex. It is related to how a word is formed, rather than the sexual gender involved.

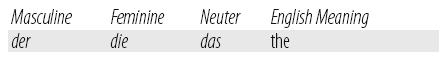

Der is used frequently with males: der Vater, der Professor, der Student. Die is used frequently with females: Der die Mutter, die Frau, die Tante (aunt). But that’s where it ends, because the three genders, denoted by the articles der, die, and das, depend more on word formation than anything else to determine what is masculine, feminine, or neuter.

English speakers must clear their minds of the idea that gender is strictly sexual and animate or inanimate. When you speak German, you must accept the idea that masculine nouns, which use der as their definite article, do not necessarily refer to males. Likewise, feminine nouns, which use die as their definite article, do not always refer to females. And neuter nouns, which use das as their definite article, do not refer exclusively to inanimate objects.

Person, Place, or Thing?

In many German language textbooks, students are told that they must simply memorize the gender of each noun. That’s not very efficient, and that’s certainly not what Germans do. As they grow up with their language, German children hear the patterns of words that require a certain gender and gradually conform to them. Along the way, they memorize the exceptions. Identifying the patterns is very helpful in determining gender, and it eliminates the need for a great deal of memorization.

There are some broad rules for determining which gender a noun is. And it should be admitted early that in many cases there will be exceptions to the rules. But the rules are helpful guideposts for making intelligent choices when using der, die, or das.

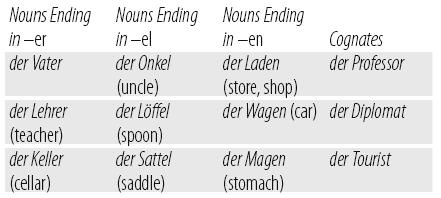

Here are four basic categories of masculine nouns. (There are more than just four, but these are a good starting point.) Many—but not all—words that end in –er, –el, or –en tend to be masculine. In addition, cognates that refer to men also tend to be masculine. Take a look at some examples.

Determining the Gender of Masculine Nouns

Determining the Gender of Masculine Nouns

Notice that half of the words listed above are inanimate objects. But all are masculine.

Additionally, nouns ending in –ling are always masculine.

der Frühling (spring)

der Frühling (spring)

der Neuling (novice, beginner)

der Neuling (novice, beginner)

der Sperling (sparrow)

der Sperling (sparrow)

Nouns ending in –ig and –ich are masculine.

der König (king)

der König (king)

der Teppich (rug, carpet)

der Teppich (rug, carpet)

Many words of one syllable that end in a consonant are masculine.

der Arzt (doctor)

der Arzt (doctor)

der Brief (letter)

der Brief (letter)

der Stuhl (chair)

der Stuhl (chair)

der Bus (bus)

der Bus (bus)

der Tag (day)

der Tag (day)

der Film (film)

der Film (film)

der Tisch (table)

der Tisch (table)

der Freund (male friend)

der Freund (male friend)

der Wein (wine)

der Wein (wine)

der Markt (market)

der Markt (market)

der Zug (train)

der Zug (train)

der Park (park)

der Park (park)

der Platz (market square, place, theater seat)

der Platz (market square, place, theater seat)

The Feminine Nouns

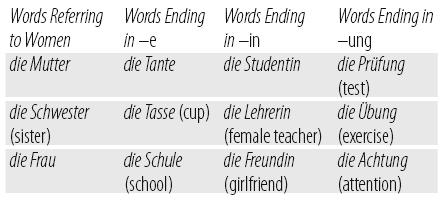

There are categories of feminine nouns that will help you determine the feminine gender. Words that refer exclusively to women are usually (but not always) feminine. Words that refer to women and inanimate objects ending in –e tend to be feminine. Words ending in –in are feminine. Words that end in –ung are feminine. Look at these examples:

Determining the Gender of Feminine Nouns

Determining the Gender of Feminine Nouns

Notice how many of these words are inanimate objects. Yet they are all feminine.

Feminine nouns ending in –in usually have a masculine counterpart that does not have that ending. The two forms distinguish males and females having the same role. Here are some examples:

Gendered Roles

Gendered Roles

| The Male Role | The Female Role |

| der Arzt (physician) | die Ärztin (physician) |

| der Freund (boyfriend) | die Freundin (girlfriend) |

| der Künstler (artist) | die Künstlerin (artist) |

| der Sänger (singer) | die Sängerin (singer) |

| der Schüler (pupil) | die Schülerin (pupil) |

Additionally, nouns ending in –schaft are always feminine.

die Botschaft (message, embassy)

die Botschaft (message, embassy)

die Wirtschaft (economy)

die Wirtschaft (economy)

die Freundschaft (friendship)

die Freundschaft (friendship)

die Wissenschaft (science)

die Wissenschaft (science)

die Landschaft (landscape)

die Landschaft (landscape)

Words that end in –ei are feminine:

die Bäckerei (bakery)

die Bäckerei (bakery)

die Konditorei (confectioner)

die Konditorei (confectioner)

die Metzgerei (butcher’s shop)

die Metzgerei (butcher’s shop)

Words that end in –tät are feminine:

die Qualität (quality)

die Qualität (quality)

die Universität (university)

die Universität (university)

Nouns ending in –heit, –keit, and –ie are always feminine:

die Einsamkeit (loneliness)

die Einsamkeit (loneliness)

die Gesundheit (health)

die Gesundheit (health)

die Poesie (poetry)

die Poesie (poetry)

Both German and English have inherited a large number of words that end in –tion. In German they are always feminine, and they usually have the same meaning as their English counterpart. But the German pronunciation of –tion is different from English: Position (poh-zee-tsee-OHN), Situation (zit-oo-ah-tsee-OHN). Look at the following words:

die Formation

die Formation

die Information

die Information

die Inspektion

die Inspektion

die Koalition

die Koalition

die Konstitution

die Konstitution

die Position

die Position

die Reservation

die Reservation

die Revolution

die Revolution

die Situation

die Situation

die Ventilation

die Ventilation

die Vibration

die Vibration

The Neuter Nouns

Let’s start with a reminder: Not all inanimate nouns in German are neuter (das). There are patterns to watch for when deciding whether a noun is neuter. Diminutives are always neuter. They end either in –chen or –lein. Words that end in –um or –ium are always neuter. Words that begin with the prefix Ge– tend to be neuter. Look at these examples:

Neuter Nouns

Neuter Nouns

| Diminutive with –chen or –lein | Ending –um or –ium | Prefix Ge– |

| das Mädchen (girl) | das Datum (date) | das Gemüse (vegetables) |

| das Fräulein (young lady) | das Studium (study) | das Getreide (grain) |

| das Brötchen (bread roll) | das Gymnasium (prep school) | das Gespenst (ghost) |

Note that some of these neuter words refer to people rather than to inanimate objects.

Another category of neuter nouns is infinitives that are used as nouns. These are always neuter.

das Einkommen (income)

das Einkommen (income)

das Singen (singing)

das Singen (singing)

das Schreiben (writing)

das Schreiben (writing)

das Essen (food)

das Essen (food)

das Tanzen (dancing)

das Tanzen (dancing)

Certain categories of words tend to be of one gender. Take note of how the following words are related and of their gender.

A Category of Words That Share the Same Gender— Das Metall (Metal)

A Category of Words That Share the Same Gender— Das Metall (Metal)

| English | German |

| aluminum | das Aluminium |

| brass | das Messing |

| gold | das Gold |

| iron | das Eisen |

| lead | das Blei |

| silver | das Silber |

| tin | das Zinn |

German wouldn’t be German without an exception. The metals have one, too: der Stahl (steel).

Exceptions to the Gender Patterns

Since there are exceptions in the various patterns, here are just a few to consider:

das Bett (bed)

das Bett (bed)

das Bier (beer)

das Bier (beer)

das Brot (bread)

das Brot (bread)

die Fabel (fable)

die Fabel (fable)

das Fahrrad (bike)

das Fahrrad (bike)

das Flugzeug (airplane)

das Flugzeug (airplane)

der Franzose (Frenchman)

der Franzose (Frenchman)

der Geschmack (taste)

der Geschmack (taste)

das Glas (glass)

das Glas (glass)

das Kind (child)

das Kind (child)

das Konzert (concert)

das Konzert (concert)

der Junge (boy)

der Junge (boy)

die Schwester (sister)

die Schwester (sister)

die Tochter (daughter)

die Tochter (daughter)

das Wasser (water)

das Wasser (water)

das Wetter (weather)

das Wetter (weather)

das Wochenende (weekend)

das Wochenende (weekend)

die Wurst (sausage)

die Wurst (sausage)

You’ve learned that many words that end in –e are feminine: die Dame (lady), die Tasse (cup), die Lampe (lamp), and so on. But there are several masculine words that end in –e, too. Memorize these so you can remember that they don’t follow the rule.

Masculine Nouns Ending in –e

Masculine Nouns Ending in –e

| German Noun | English Meaning |

| der Alte | old man |

| der Buchstabe | letter (of the alphabet) |

| der Franzose | Frenchman |

| der Hase | hare |

| der Junge | boy |

| der Knabe | boy, lad |

| der Löwe | lion |

| der Matrose | sailor |

| der Name | name |

| der Neffe | nephew |

| der Ochse | ox |

Exceptions to the rules, like those words listed above, will always exist. With these words, there is no getting around memorizing their gender when you learn the noun.

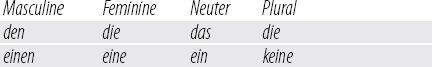

In German, the articles and indefinite articles that you learned here are called the nominative case. This simply means that these nouns are acting as the subjects of sentences.

Articles Are Important

Just like English, German has definite and indefinite articles. Definite articles refer to specific persons or things (the man, the woman, the child), and indefinite articles refer to unspecific persons or things (a man, a woman, a child).

The articles you have learned so far are the definite articles. Let’s review them.

Definite Articles and Gender

Definite Articles and Gender

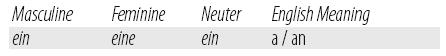

The gender patterns that you encountered earlier in this chapter work the same with indefinite articles. But the good news is that you only have to keep your eye on feminine nouns when choosing the indefinite article. Masculine and neuter nouns have the same form: ein. The feminine indefinite article is eine.

Indefinite Articles and Gender

Indefinite Articles and Gender

Look at these examples to see how they relate to the definite articles:

Comparing the Indefinite and Definite Articles

Comparing the Indefinite and Definite Articles

| Masculine Nouns | Feminine Nouns | Neuter Nouns |

| der Mann / ein Mann | die Frau / eine Frau | das Kind / ein Kind |

| der Laden / ein Laden | die Klasse / eine Klasse | das Studium / ein Studium |

| der Onkel / ein Onkel | die Freundin / eine Freundin | das Geschenk / ein Geschenk |

Making Nouns Plural

So you understand articles and that all nouns have gender. But what about when there are more than one of something? In this section you’ll learn how to talk about men, women, cars, books, and anything else you can have two or more of, plus you’ll learn how to use pronouns so you don’t have to keep repeating yourself.

Several German nouns are identical in both the singular and plural. You can tell when the noun is plural only by the verb used with it or by a number preceding it. Look at these examples:

| ein Brunnen ist . . . | a well is . . . |

| zehn Brunnen sind . . . | ten wells are . . . |

| ein Mädchen ist . . . | a girl is . . . |

| zehn Mädchen sind . . . | ten girls are . . . |

| ein Schauspieler ist . . . | an actor is . . . |

| zehn Schauspieler sind . . . | ten actors are . . . |

When a noun is plural, it uses die as its definite article, no matter what its gender. Very few German nouns form their plural by adding an –s, though a few do follow that pattern. See the following table for some examples.

Making a Noun Plural by Adding an –s

Making a Noun Plural by Adding an –s

| Singular Noun | Plural Noun |

| der Park (park) | die Parks (parks) |

| das Foto (photo) | die Fotos (photos) |

| die Kamera (camera) | die Kameras (cameras) |

This is the simplest way that plurals may be formed, but it is not the typical way. Most plurals are formed in other ways, similar to irregular plurals in English, such as child/children, mouse/mice, goose/geese.

The Plural of Masculine Nouns

Masculine nouns that end in –er, –el, or –en have no ending in the plural, but they may require adding an Umlaut. Some examples with masculine nouns are shown in the following table.

Plural of Masculine Nouns Ending in –er, –el, or –en

Plural of Masculine Nouns Ending in –er, –el, or –en

| Singular Noun | Plural Noun with Numbers | Plural Noun with Definite Article |

| der Schauspieler (the actor) | sechs Schauspieler (six actors) | die Schauspieler (the actors) |

| der Löffel (the spoon) | zwei Löffel (two spoons) | die Löffel (the spoons) |

| der Laden (the shop) | acht Läden (eight shops) | die Läden (the shops) |

| der Vater (the father) | drei Väter (three fathers) | die Väter (the fathers) |

Note how Laden and Vater have added an Umlaut above the a in the plural form.

Other masculine nouns, particularly short, one-syllable nouns, usually form their plural by adding –e to the noun. Often an Umlaut is required.

Masculine Plural Ending –e

Masculine Plural Ending –e

| Singular Noun | Plural Noun with Numbers | Plural Noun with Definite Article |

| der Abend (the evening) | zwei Abende (two evenings) | die Abende (the evenings) |

| der Brief (the letter) | sechs Briefe (six letters) | die Briefe (the letters) |

| der Bus (the bus) | zwei Busse (two buses) | die Busse (the buses) |

| der Markt (the market) | drei Märkte (three markets) | die Märkte (the markets) |

| der Sohn (the son) | vier Söhne (four sons) | die Söhne (the sons) |

| der Stuhl (the chair) | vier Stühle (four chairs) | die Stühle (the chairs) |

| der Tag (the day) | zehn Tage (ten days) | die Tage (the days) |

| der Zug (the train) | acht Züge (eight trains) | die Züge (the trains) |

One high-frequency masculine noun that doesn’t follow these patterns is der Mann (man). It forms its plural by adding an Umlaut and the ending –er: zwei Männer (two men), die Männer (the men).

Feminine Nouns in the Plural

Just like masculine nouns, feminine nouns don’t change to the plural by simply adding an –s. Most feminine nouns change to the plural by adding –n or –en. And just like all other plural nouns, they use die as the definite article.

Forming Plurals of Feminine Nouns by Adding –n or –en

Forming Plurals of Feminine Nouns by Adding –n or –en

| Singular | Plural |

| die Frau (the woman) | die Frauen (the women) |

| die Schwester (the sister) | die Schwestern (the sisters) |

| die Straße (the street) | die Straßen (the streets) |

| die Tasse (the cup) | die Tassen (the cups) |

If a feminine noun ends in –in, the plural ending is –nen. Die Freundin (girlfriend) becomes die Freundinnen (girlfriends).

There are two notable exceptions to the rule regarding –n or –en for feminine nouns. Note that the only change in these two words is the addition of an Umlaut in the plural:

die Mutter (mother) / die Mütter (mothers)

die Mutter (mother) / die Mütter (mothers)

die Tochter (daughter) / die Töchter (daughters)

die Tochter (daughter) / die Töchter (daughters)

Making Neuter Nouns Plural

Many neuter words follow a similar pattern to some masculine words: There is no ending change in the plural. Examples:

Neuter Plural Formation for Nouns That Take No Ending

Neuter Plural Formation for Nouns That Take No Ending

| Singular | Plural |

| das Fenster (the window) | die Fenster (the windows) |

| das Klassenzimmer (the classroom) | die Klassenzimmer (the classrooms) |

| das Mädchen (the girl) | die Mädchen (the girls) |

Neuter words, particularly those of one syllable, tend to form their plural by the ending –er. An Umlaut may also be added in some cases.

Neuter Plural Formation for Nouns That Take an –er Ending

Neuter Plural Formation for Nouns That Take an –er Ending

| Singular | Plural |

| das Fahrrad (the bicycle) | die Fahrräder (the bicycles) |

| das Glas (the glass) | die Gläser (the glasses) |

| das Haus (the house) | die Häuser (the houses) |

| das Kind (the child) | die Kinder (the children) |

| das Land (the country) | die Länder (the countries) |

Words that end in –chen and –lein change just the article from das to die; no endings are added. Das Mädchen (the girl) becomes die Mädchen (the girls), das Röslein (the little rose) becomes die Röslein (the little roses).

Be aware that these rules regarding plural formations show only a tendency. They are meant to help guide you. But there will always be exceptions. Using German plurals accurately will come with experience and time.

Pronouns

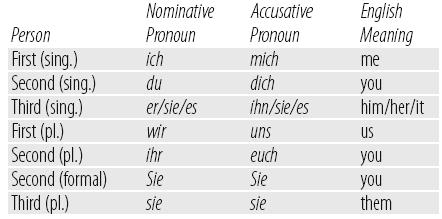

Now that you have a feeling for German gender, it’s time to meet the pronouns that go along with the gender of nouns. Pronouns are words that take the place of a noun. They follow the patterns you have already learned with nouns. Interestingly, the German pronouns for “he,” “she,” and “it” resemble very much the definite articles.

Third Person Singular Pronouns

Third Person Singular Pronouns

| Gender | Definite Article | Pronoun |

| masculine | der | er (he or it) |

| feminine | die | sie (she or it) |

| neuter | das | es (he, she, or it) |

Remember that German gender is not based on sexual gender. That’s why er means both “he” and “it,” and sie means both “she” and “it.” It depends on the meaning of the noun. Look at these examples:

Pronoun Substitution

Pronoun Substitution

| Noun Subject | Pronoun Replacement | Translation |

| Der Mann ist da. | Er ist da. | He is there. |

| Der Mantel ist da. | Er ist da. | It is there. |

| Die Studentin ist in der Stadt. | Sie ist in der Stadt. | She is in the city. |

| Die Schule ist in der Stadt. | Sie ist in der Stadt. | It is in the city. |

| Das Kind ist hier. | Es ist hier. | He/she is here. |

| Das Geschenk ist hier. | Es ist hier. | It is here. |

You and I

In addition to the third person pronouns that you just learned, you should know the first and second person personal pronouns.

Personal Pronouns—Singular

Personal Pronouns—Singular

| Person | English Pronoun | German Pronoun |

| First | I | ich |

| Second | you | du (informal), Sie (formal) |

| Third | he, she, it | er, sie, es |

Sie is the formal way to say “you,” which you would use with anyone you don’t know or anyone older than you or in a position of authority. There’s no exact English equivalent. It is always capitalized. And don’t let the word for “she” or “it” (sie) confuse you, even though it looks the same—it’s always spelled with a lowercase letter except at the beginning of a sentence.

The German word for the pronoun “I” is ich and is never capitalized except at the beginning of a sentence. It’s just the opposite of English.

Plural Pronouns

To talk about nouns that are plural without repeating them over and over, you’ll need to use the plural pronouns.

Personal Pronouns—Plural

Personal Pronouns—Plural

| Person | English Pronoun | German Pronoun |

| First | we | wir |

| Second | you all | ihr |

| Third | they | sie |

Here are some examples:

Vater und Mutter becomes sie (pl.)

Vater und Mutter becomes sie (pl.)

Benno und Ilse becomes sie (pl.)

Benno und Ilse becomes sie (pl.)

Karl und ich becomes wir

Karl und ich becomes wir

der Schüler und ich becomes wir

der Schüler und ich becomes wir

Using You

German has three different pronouns that mean “you,” as you have now seen. German has a plural, informal pronoun (the plural of du). It is ihr. Yes, it also means “you.” And, of course, you’ve already encountered Sie, which is the formal pronoun “you.” So let’s look at those forms of “you” again and put them in perspective.

| du (you, sing.) | used to address one person on an informal or familiar basis |

| ihr (you, pl.) | used to address more than one person on an informal or familiar basis |

|

Sie (you, sing. or pl.) | used to address one or more persons on a formal basis |

“Informal” here means that the person to whom you are speaking is a relative or a close friend and you are on a first-name basis with one another. “Formal” here means that the person to whom you are speaking is older, in a position of respect or authority, or is someone you don’t know well. You use a title and a last name when addressing this person: Herr Braun, Professor Brenner, Doktor Schmidt.

Adjectives and Where They Stand

Just like English adjectives, German adjectives can stand alone at the end of a phrase to describe a noun in a sentence. These adjectives are called predicate adjectives.

The child is little. Das Kind ist klein.

The child is little. Das Kind ist klein.

Uncle Jack is young. Onkel Hans ist jung.

Uncle Jack is young. Onkel Hans ist jung.

Grandmother gets furious. Großmutter wird wütend.

Grandmother gets furious. Großmutter wird wütend.

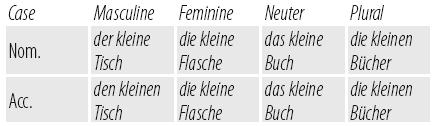

In this regard, German and English adjectives are used in the very same way. But when an adjective stands directly in front of a noun, that’s where English and German differ. German adjectives add an ending when they stand in front of a noun.

The little child is sad. Das kleine Kind ist traurig.

The little child is sad. Das kleine Kind ist traurig.

The young man is playing soccer. Der junge Mann spielt Fußball.

The young man is playing soccer. Der junge Mann spielt Fußball.

The old lady likes it. Die alte Dame hat es gern.

The old lady likes it. Die alte Dame hat es gern.

When using the definite article (der, die, das) with a singular noun, the adjective ending is –e. But if the noun is plural, the ending is –en.

Das kleine Kind ist traurig. Die kleinen Kinder sind traurig.

Das kleine Kind ist traurig. Die kleinen Kinder sind traurig.

Der junge Mann spielt Fußball. Die jungen Männer spielen Fußball.

Der junge Mann spielt Fußball. Die jungen Männer spielen Fußball.

Die alte Dame hat es gern. Die alten Damen haben es gern.

Die alte Dame hat es gern. Die alten Damen haben es gern.

Adjectives

Adjectives

| German | English |

| arm | poor |

| kurz | short |

| blau | blue |

| lang | long |

| braun | brown |

| langweilig | boring |

| gelb | yellow |

| neu | new |

| grau | gray |

| reich | rich |

| grün | green |

| rot | red |

| hässlich | ugly |

| schwarz | black |

| hübsch | beautiful/handsome |

| weiß | white |

| interessant | interesting |

Here are some examples of predicate adjectives (which take no endings) compared to adjectives in front of the nouns they modify (which do take endings).

Die Lehrerin ist alt. (The teacher is old.)

Die Lehrerin ist alt. (The teacher is old.)

die alte Lehrerin (the old teacher)

die alte Lehrerin (the old teacher)

Das Kind ist klein. (The child is small.)

Das Kind ist klein. (The child is small.)

das kleine Kind (the small child)

das kleine Kind (the small child)

Die Kinder sind traurig. (The children are sad.)

Die Kinder sind traurig. (The children are sad.)

die traurigen Kinder (the sad children)

die traurigen Kinder (the sad children)

Die Frauen sind hübsch. (The women are beautiful.)

Die Frauen sind hübsch. (The women are beautiful.)

die hübschen Frauen (the beautiful women)

die hübschen Frauen (the beautiful women)

Die Vase ist grün. (The vase is green.)

Die Vase ist grün. (The vase is green.)

die grüne Vase (the green vase)

die grüne Vase (the green vase)

Verbs: Infinitives, Auxiliaries, and Conjugations

A verb is one of the most important elements of any language. They tell what’s going on: singing, running, fighting, crying, sleeping, drinking, talking, loving, and . . . on and on. Here you’ll learn how to conjugate verbs and form sentences. Before long, you’ll be speaking like a native!

Conjugate What?

Infinitives, in any language, are the basic form of verbs. In English, infinitives begin with the word “to” and look like this: to run, to jump, to follow, to argue, to be. In German they end in –n or –en: sein, gehen, heißen.

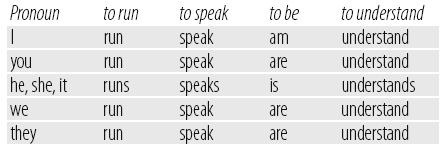

Conjugating a verb means to put the appropriate endings on the verb that correspond to the various pronouns. In English that’s a relatively simple matter. You drop the word “to” from the infinitive and add an –s to the third person singular (he, she, it). Look at the example here.

Verb Endings in English

Verb Endings in English

When it comes to verbs, English is a little more complicated than German. Watch out for the two present tense forms that we have in English. German has only one. And both English forms are translated into German the same way. Look at these examples:

I buy a house. Ich kaufe ein Haus.

I buy a house. Ich kaufe ein Haus.

I am buying a house. Ich kaufe ein Haus.

I am buying a house. Ich kaufe ein Haus.

He goes home. Er geht nach Hause.

He goes home. Er geht nach Hause.

He is going home. Er geht nach Hause.

He is going home. Er geht nach Hause.

The German Verb

You have already learned a bit about one of the most important verbs in German: sein. That’s the infinitive form of the verb “to be.”

Conjugating sein (to be)

Conjugating sein (to be)

| Person | English Conjugation | German Conjugation |

| First (sing.) | I am | ich bin |

| Second (sing.) | you are (informal) | du bist |

| Third (sing.) | he is, she is, it is | er ist, sie ist, es ist |

| First (pl.) | we are | wir sind |

| Second (pl.) | you are | ihr seid |

| Second (sing., pl.) | you are (formal) | Sie sind |

| Third (pl.) | they are | sie sind |

You probably have noticed that there are three pronouns in German that look an awfully lot alike: sie (she), Sie (you formal), sie (they). Germans have no problem distinguishing these pronouns, because their usage is so specific. For one thing, sie ist can mean only “she is,” because the verb ist is used only with er, sie (she), and es. And the context of a conversation would make clear whether Sie (you formal) or sie (they) is meant.

In this book, you will know that “you” is the meaning of Sie when you see it with a capitalized S. The other two forms will be identified as singular and plural. If you see sie (sing.), you will know that it means “she.” If you see sie (pl.), you will know it means “they.”

Going Somewhere? Verbs of Motion

It’s time to start moving around a little more. Let’s look at four verbs that are called verbs of motion. They describe how you get from one place to another: gehen (GAY-EN), to go on foot; kommen (KAW-men), to come; fliegen (FLEE-gen), to fly; and fahren (FAHR-en), to drive or to go by transportation.

They’re used almost in the same way that their English counterparts are used, except that German tends to be a little more specific. In English we say, “I go to school.” We don’t tell whether we walk there, drive there, or fly there. In German there’s a tendency to specify the means of conveyance: walking, driving, or flying.

To learn how to conjugate these verbs, you need to know the term “verb stem.” A verb stem is the part of the infinitive remaining when you drop the final –en: fahren/fahr, gehen/geh, and so on. You add endings to the verb stem to conjugate each verb according to the person and number (singular or plural). Take a look at the following table.

Conjugational Endings of Verbs

Conjugational Endings of Verbs

| Person | Ending to Add to Verb Stem | Example |

| First (sing.) | –e | ich gehe |

| Second (sing.) | –st | du gehst |

| Third (sing.) | –t | er, sie, es geht |

| First (pl.) | –en | wir gehen |

| Second (pl.) | –t | ihr geht |

| Second formal (sing. or pl.) | –en | Sie gehen |

| Third (pl.) | –en | sie gehen |

Now let’s look at the conjugations of these verbs of motion.

Conjugating Verbs of Motion

Conjugating Verbs of Motion

| gehen | kommen | fliegen | fahren |

| ich gehe | ich komme | ich fliege | ich fahre |

| du gehst | du kommst | du fliegst | du fährst |

| er/sie/es geht | er/sie/es kommt | er/sie/es fliegt | er/sie/es fährt |

| wir gehen | wir kommen | wir fliegen | wir fahren |

| ihr geht | ihr kommt | ihr fliegt | ihr fahrt |

| Sie gehen | Sie kommen | Sie fliegen | Sie fahren |

| sie (pl.) gehen | sie kommen | sie fliegen | sie fahren |

Notice that the second person singular and third person singular (du, er, sie, es) add an Umlaut in their conjugation of the verb fahren: du fährst, er fährt, sie fährt, es fährt. This is called a stem change.

Let’s look at some examples of ways to use these verbs.

Ihr kommt aus Berlin. (You all come from Berlin.)

Ihr kommt aus Berlin. (You all come from Berlin.)

Wir fliegen nach Hause. (We fly home.)

Wir fliegen nach Hause. (We fly home.)

Er fährt mit dem Bus. (He goes [drives] by bus.)

Er fährt mit dem Bus. (He goes [drives] by bus.)

Ich gehe mit Hans. (I go with Hans.)

Ich gehe mit Hans. (I go with Hans.)

Sie fahren mit dem Zug. (They are going by train.)

Sie fahren mit dem Zug. (They are going by train.)

The phrase kommen aus is used regularly to tell what city, locale, or country you come from: Ich komme aus Hamburg. Er kommt aus Bayern (Bavaria). Wir kommen aus Amerika.

Essentials for Life: Eating and Drinking

Essen (ESS-en) (to eat) and trinken (TRIN-ken) (to drink) are not verbs of motion. But notice that their conjugation follows the same pattern as the other verbs you have learned.

Take note that the verb essen, like fahren, requires a slight change in the second and third person singular (du, er, sie, es): du isst, er isst, sie isst, es isst.

Conjugating essen and trinken

Conjugating essen and trinken

| essen | trinken |

| ich esse | ich trinke |

| du isst | du trinkst |

| er/sie/es isst | er/sie/es trinkt |

| Sie essen | Sie trinken |

| wir essen | wir trinken |

| ihr esst | ihr trinkt |

| sie (pl.) essen | sie trinken |

Present Tense

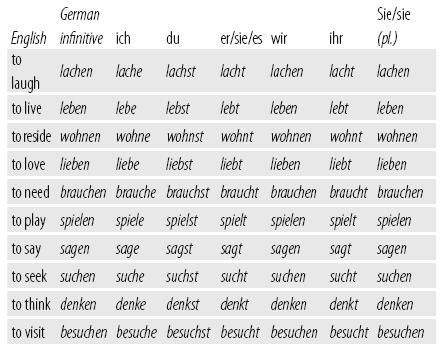

Now that you know how to put the correct endings on German verbs, it’s time to start collecting some useful ones to add to your vocabulary.

Present Tense Conjugations of Some New Verbs

Present Tense Conjugations of Some New Verbs

Watch out for leben and wohnen. The former means “to live, to be alive.” The latter means “to live or reside” somewhere. Andreas lebt wie ein König. (Andreas lives like a king.) Andreas wohnt jetzt in Berlin. (Andreas is living in Berlin now.)

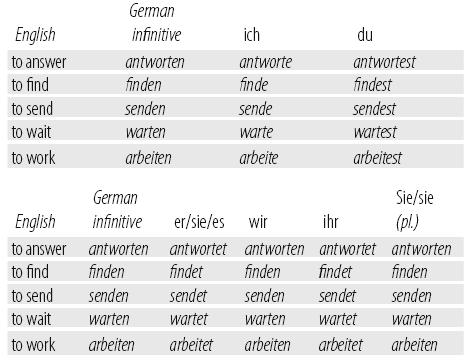

Below are five more new verbs to add to your German vocabulary. But they have a variation in the verb stem that you’ll have to watch for.

If a German verb stem ends in –d or –t, you have to add an extra –e before adding a –t or an –st ending. This makes the conjugated verb easier to pronounce. You’ll remember that the –t ending is needed after er, sie, es, and ihr and –st is used after du. Look at these examples:

Verb Stems Ending in –t or –d

Verb Stems Ending in –t or –d

Verbs That End in -ieren

There are numerous patterns of words that help to build a vocabulary rapidly. Another pattern is the verb ending –ieren. Verbs that have this ending tend to be very similar to English. And they’re all regular verbs, so they don’t require a change to the stem in conjugations.

Here are some useful words to learn:

akzeptieren (to accept)

akzeptieren (to accept)

arrangieren (to arrange)

arrangieren (to arrange)

diskutieren (to discuss)

diskutieren (to discuss)

isolieren (to isolate)

isolieren (to isolate)

konfiszieren (to confiscate)

konfiszieren (to confiscate)

kontrollieren (to control, supervise)

kontrollieren (to control, supervise)

kritisieren (to criticize)

kritisieren (to criticize)

marschieren (to march)

marschieren (to march)

fotografieren (to photograph)

fotografieren (to photograph)

reduzieren (to reduce)

reduzieren (to reduce)

reparieren (to repair)

reparieren (to repair)

reservieren (to reserve)

reservieren (to reserve)

riskieren (to risk)

riskieren (to risk)

studieren (to study)

studieren (to study)

A Very Versatile Verb

The word bitten is one of the most frequently used German words. It has more than just one meaning, of course.

Bitten means “to ask, to request” or “to beg.” But it doesn’t have anything to do with asking questions. It refers to asking someone to do something: “He asks her to remove her hat.” “The teacher asks the class to remain very quiet.”

Er bittet sie, stehen zu bleiben. (He asks them to remain standing.)

Er bittet sie, stehen zu bleiben. (He asks them to remain standing.)

Ich bitte ihn, nach Hause zu kommen. (I ask him to come home.)

Ich bitte ihn, nach Hause zu kommen. (I ask him to come home.)

In addition, you will often hear the word when you walk up to a salesperson in a store. “Bitte,” the salesperson will say cheerfully. Or, “Bitte schön.” It’s comparable to “May I help you?” in English.

When the salesperson hands you your purchase, he or she might also say, “Bitte schön.” In this case it means something like “here you are” or “here’s your package.”

And when you thank the salesperson (danke schön), the response will be “bitte schön” or “bitte sehr” (you’re welcome).

Negation

To negate a sentence in German, you can use the word nicht (not). The word nicht comes after the verb.

Ich bin nicht Peter. (I am not Peter.)

Ich bin nicht Peter. (I am not Peter.)

Er wohnt nicht in München. (He does not live in Munich.)

Er wohnt nicht in München. (He does not live in Munich.)

Sie studiert nicht französisch. (She is not studying French.)

Sie studiert nicht französisch. (She is not studying French.)

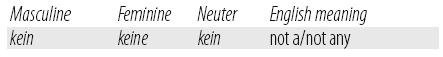

However, if you use a sentence that uses the indefinite article ein, you can’t use nicht. To negate ein, you use the word kein (KINE), which means “not any” or “no.” Kein always replaces ein.

Ich habe kein Geld. (I don’t have any money.)

Ich habe kein Geld. (I don’t have any money.)

Ich habe keinen Teller. (I have no plate.)

Ich habe keinen Teller. (I have no plate.)

The same endings that you learned to use with ein must also be used with kein. You’ll learn more about the endings that ein-words can take in the next chapter.

Negating ein in the Genders

Negating ein in the Genders

Sie sehen eine Brücke. Sie sehen keine Brücke. (They see a bridge. They don’t see a bridge.)

Sie sehen eine Brücke. Sie sehen keine Brücke. (They see a bridge. They don’t see a bridge.)

Ich kaufe einen Teller. Ich kaufe keinen Teller. ( I buy a plate. I don’t buy a plate.)

Ich kaufe einen Teller. Ich kaufe keinen Teller. ( I buy a plate. I don’t buy a plate.)

Irregular Verbs

Now that you’ve learned the basics about German verbs, it’s time to look more closely at some verbs that take stem changes in the present tense. One of the most often used is the verb “to have.” This section will also cover using the present tense to talk about the future.

The German Verb

One very common German verb is “to have”—haben. This verb, like some that you already learned, doesn’t follow the rules of conjugation exactly. In the second and third person singular, the stem of the verb (the part left after you drop the –en) changes. It’s time to become acquainted with the little irregularities found in this verb.

Conjugating haben (to have)

Conjugating haben (to have)

| Person | English Conjugation | German Conjugation |

| First (sing.) | I have | ich habe |

| Second (sing.) | you have | du hast |

| Third (sing.) | he/she/it has | er/sie/es hat |

| First (pl.) | we have | wir haben |

| Second (pl.) | you all have | ihr habt |

| Second (formal) | you have | Sie haben |

| Third (pl.) | they have | sie (pl.) haben |

Practice saying the conjugation of the verb and place it in your memory. It’s a very important verb to know. And just like sein, you can use it in a sentence with heute to indicate the present tense.

Maria hat ein Examen. (Maria has an exam.)

Maria hat ein Examen. (Maria has an exam.)

Heute haben wir eine Übung. (We are having an

Heute haben wir eine Übung. (We are having an

exercise today.)

Ich habe eine Klasse. (I have a class.)

Ich habe eine Klasse. (I have a class.)

Du hast es. (You have it.)

Du hast es. (You have it.)

Er hat eine Prüfung. (He has a test.)

Er hat eine Prüfung. (He has a test.)

Expressing Like with Haben

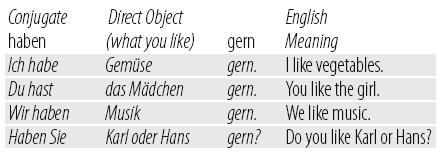

German has a special way of saying that a person likes someone or something. To express “like” in German, conjugate haben, say what it is you like, and follow the whole phrase with the word gern.

Using gern haben to Express Like

Using gern haben to Express Like

You can also use gern following other verbs to show that you like doing something:

Ich esse gern Obst. (I like eating fruit.)

Ich esse gern Obst. (I like eating fruit.)

Er trinkt gern Bier. (He likes drinking beer.)

Er trinkt gern Bier. (He likes drinking beer.)

Wir singen gern. (We like singing.)

Wir singen gern. (We like singing.)

This is a very common phrase and one you should put in your treasury of vocabulary.

The Word Morgen

Morgen means “tomorrow” and indicates that something is occurring in the future. It is an adverb that tells “when” something is occurring. But you can use the present tense of a verb and still mean the future. It’s just like English. You can specify the time by “today” or “tomorrow” using only a present tense verb.

Today he is in Germany.

Today he is in Germany.

Tomorrow he is in Germany.

Tomorrow he is in Germany.

Look at some German examples:

Heute sind wir in Hamburg. (We are in Hamburg today.)

Heute sind wir in Hamburg. (We are in Hamburg today.)

Morgen sind wir in Hamburg. (We are in Hamburg tomorrow.)

Morgen sind wir in Hamburg. (We are in Hamburg tomorrow.)

Heute habe ich eine Prüfung. (I have a test today.)

Heute habe ich eine Prüfung. (I have a test today.)

Morgen habe ich eine Prüfung. (I have a test tomorrow.)

Morgen habe ich eine Prüfung. (I have a test tomorrow.)

You can also use the present tense to infer a future meaning using the verbs of motion that you learned earlier.

Heute kommt er ins Kino. (He is coming to the movies today.)

Heute kommt er ins Kino. (He is coming to the movies today.)

Morgen kommt er ins Kino. (He is coming to the movies tomorrow.)

Morgen kommt er ins Kino. (He is coming to the movies tomorrow.)

Heute fliegen wir nach Hause. (We are flying home today.)

Heute fliegen wir nach Hause. (We are flying home today.)

Morgen fliegen wir nach Hause. (We are flying home tomorrow.)

Morgen fliegen wir nach Hause. (We are flying home tomorrow.)

Stem Changes in the Present Tense

You learned early that German has some special forms in the present tense. The verb fahren, for example, requires an Umlaut in the second person singular (du) and third person singular (er, sie, es): ich fahre, du fährst, er fährt, and so on.

Three other verbs you should know fall into the same category of special changes. But notice that each verb has its own peculiar way of changing. The verb wissen (to know) becomes a new form, the verb sprechen (to speak) changes the vowel –e to –i, and the verb laufen (to run) adds an Umlaut.

The Conjugation of wissen, sprechen, and laufen

The Conjugation of wissen, sprechen, and laufen

Be careful of the spelling of the conjugation of wissen. There is no ending on the stem of the verb weiß with the pronouns ich, er, sie, and es. And with the pronoun du you only add a –t to the stem weiß (du weißt).

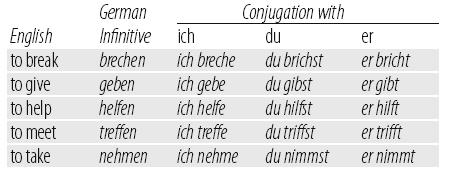

There aren’t many verbs that change their form the way wissen does. But there are lots of useful words that follow the pattern of sprechen and laufen. Many words that have an e in the verb stem, like sprechen, change that e to an i or ie. And words that have the vowel a in the stem often add an Umlaut, like laufen. But remember that these little changes only occur in the second person singular (du) and the third person singular (er, sie, es). Here are some examples.

Verbs That Change e to i

Verbs That Change e to i

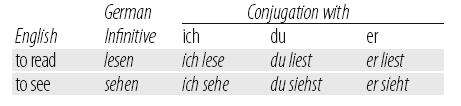

Verbs That Change e to ie

Verbs That Change e to ie

Verbs That Change a to ä

Verbs That Change a to ä

The Many Uses of Werden

Werden is a frequently used verb in German. It means “to become” or “to get” (She becomes a doctor. It’s getting warm).

Its conjugation follows the pattern you already know, with a slight variation in the second and third persons singular.

Conjugating werden (to get/to become)

Conjugating werden (to get/to become)

| Person | English Conjugation | German Conjugation |

| First (sing.) | I get / I become | ich werde |

| Second (sing.) | you get / you become | du wirst |

| Third (sing.) | he/she/it gets / he/she/it becomes | er/sie/es wird |

| First (pl.) | we get / we become | wir werden |

| Second (pl.) | you all get / you all become | ihr werdet |

| Second (formal) | you get / you become | Sie werden |

| Third (pl.) | they get / they become | sie werden |

Past Tense

In German, there are two types of past tense, regular and irregular. Don’t let it worry you. Fortunately for you as an English speaker, you have the advantage of knowing very similar past tense patterns in your native language.

For now you’re just going to concentrate on the regular past tense. In English, that’s where you tack on the ending “–ed” to a verb, and it takes on a past tense meaning.

| he jumps | he jumped |

| we look | we looked |

| I travel | I traveled |

Just think of all the English verbs there are that form their past tense by this simple method. The German method is just as easy. Just add –te to the stem of the verb and it becomes past tense.

Forming the Past Tense

Forming the Past Tense

| Infinitive | Verb Stem | Past Tense |

| spielen (to play) | spiel | spielte |

| fragen (to ask) | frag | fragte |

| suchen (to search) | such | suchte |

If the stem of the verb ends in –t or –d, you have to add an extra –e before placing the past tense ending –te on the end of the stem:

warten (to wait) wart wartete

warten (to wait) wart wartete

After you have formed the past tense (spielte, fragte, suchte, wartete), you’re not quite done. As with all German verbs, the conjugational ending must still be added. But notice that the endings for ich, er, sie, and es are the same: –te. The past tense conjugation of regular verbs will look like the ones in the following table.

Conjugating the Past Tense

Conjugating the Past Tense

| Pronoun | spielen | fragen | warten |

| ich | spielte | fragte | wartete |

| du | spieltest | fragtest | wartetest |

| er, sie, es | spielte | fragte | wartete |

| wir | spielten | fragten | warteten |

| ihr | spieltet | fragtet | wartetet |

| Sie | spielten | fragten | warteten |

| sie (pl.) | spielten | fragten | warteten |

As you can see from the above table, there are no new conjugational endings to learn for the past tense.

This past tense formation is called das Imperfekt in German. It is used primarily to show that something was done often (Sie spielte oft Tennis. / She played tennis often.) or in a narrative that describes events that happen in sequence. Unlike English, German has one past tense form.

Comparing English and German Past Tense Forms

Comparing English and German Past Tense Forms

| English Past Tenses | German Past Tense |

| we were learning | wir lernten |

| we learned | wir lernten |

Forming Questions in the Past Tense

It is easy to ask questions in the past tense. There is no special formula for forming past tense questions. What you already know about questions in the present tense also applies to the past tense.

In German questions the verb always comes before the subject: Hast du einen Hund? (Do you have a dog?). This is true even when an interrogative word begins the sentence: Was hast du? (What do you have?). For past tense questions, merely form the past tense stem and put the proper conjugational ending on the verb.

Contrasting Present Tense and Past Tense Questions

Contrasting Present Tense and Past Tense Questions

| Present Tense | Past Tense |

| Spielst du Tennis? (Do you play tennis?) | Spieltest du Tennis? (Did you play tennis?) |

| Brauchen Sie Geld? (Do you need money?) | Brauchten Sie Geld? (Did you need money?) |

| Hören Sie Radio? (Do you listen to the radio?) | Hörten Sie Radio? (Did you listen to the radio?) |

| Lernst du Deutsch? (Are you learning German?) | Lerntest du Deutsch? (Did you learn German?) |

| Wo wohnt er? (Where does he live?) | Wo wohnte er? (Where did he live?) |

| Wer arbeitet hier? (Who works here?) | Wer arbeitete hier? (Who worked here?) |

| Wen besucht er? (Whom is he visiting?) | Wen besuchte er? (Whom did he visit?) |

| Was kauft ihr? (What are you all buying?) | Was kauftet ihr? (What did you all buy?) |

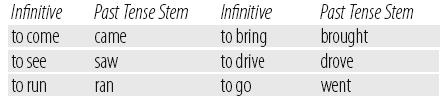

The Past Tense of Irregular Verbs

The German past tense has a long list of verbs that change to the past tense by irregular stem formations. That sounds like trouble, but for English speakers it’s really not so bad. These verbs are often called “strong verbs.” In this book they’re just going to be called “irregular.”

What you already know about the past tense will help you to use irregular verbs in the past. Regular verbs simply put a –te on the end of the stem of the verb. Then the conjugational ending is added.

But irregular verbs do something different, and it’s exactly what irregular verbs do in English: They form a completely new stem. Let’s look at some examples in English.

Verb Stems of the English Irregular Past Tense

Verb Stems of the English Irregular Past Tense

If you think about it, you can come up with a very long list of irregular verbs in English. You know them because you slowly absorbed them during your childhood.

Comparing English and German in the Past Tense

As American kids grow up, they make mistakes: Little Johnny might say, “I drinked all my milk, Mom.” But he’s only five years old. In time, he’ll know that the past tense of “drink” is “drank.”

German kids do the same thing. For a while they form all their past tense verbs like regular verbs with a –te ending. But eventually they begin to remember the irregularities and use the past tense of these verbs correctly.

And you will do the same thing. You’ll discover that German irregular past tense forms follow very closely the pattern of English past tense forms.

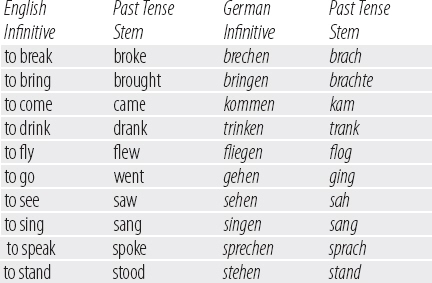

Let’s look at a list of some frequently used verbs so you can see what happens in both languages.

Irregular Verbs in English and German

Irregular Verbs in English and German

Remember that the simple past tense (das Imperfekt) is used in narratives and to show repetition.

What are some of the verbs that require stem changes in the past tense? The following table is a list of some common verbs that are irregular in the past tense. Notice how many follow a pattern similar to the English past tense.

Irregular Past Tense Stems

Irregular Past Tense Stems

| English Infinitive | German Infinitive | Past Tense Stem |

| to bake | backen | buk (or backte) |

| to be called | heißen | hieß |

| to become | werden | wurde |

| to drive | fahren | fuhr |

| to eat | essen | aß |

| to find | finden | fand |

| to give | geben | gab |

| to have | haben | hatte |

| to help | helfen | half |

| to hit | schlagen | schlug |

| to know | wissen | wusste |

| to know, be acquainted | kennen | kannte |

| to let | lassen | ließ |

| to meet | treffen | traf |

| to read | lesen | las |

| to run | laufen | lief |

| to sleep | schlafen | schlief |

| to take | nehmen | nahm |

| to think | denken | dachte |

| to wash | waschen | wusch |

| to wear, carry | tragen | trug |

| to write | schreiben | schrieb |

Conjugations in the German Irregular Past Tense

You recall from previous chapters that German verbs always have to have conjugational endings. That’s also true in the irregular past tense. You already know those endings.

Irregular Past Tense Conjugations

Irregular Past Tense Conjugations

As you can see, there’s nothing new about the conjugation of the irregular past tense. Once you know the stem, you merely use the endings you already know.

Did you notice that, like in the past tense of regular verbs, the pronouns ich, er, sie, and es do not add a conjugational ending to the stem?

The Importance of Being

The infinitive sein is a very important verb. It’s used as frequently in German as “to be” is used in English. You are very familiar with it in the present tense. But now it’s time to become familiar with its past tense.

Just like English “to be,” German sein makes a complete transformation in the past tense. “To be” becomes “was.” Sein becomes war. You’ll find that, like other irregular verbs, conjugating war is a snap.

The Past Tense of sein

The Past Tense of sein

| Person | English | German |

| First (sing.) | I was | ich war |

| Second (sing.) | you were | du warst |

| Third (sing.) | he/she/it was | er/sie/es war |

| First (pl.) | we were | wir waren |

| Second (pl.) | you all were | ihr wart |

| Second (formal) | you were | Sie waren |

| Third (pl.) | they were | sie waren |

A Special Look at Haben and Werden

These are two very common verbs in German. Alone they mean “to have” and “to become,” respectively. But they have another use—these verbs, along with sein, will be used to form the more complex perfect tenses. Watch out for these two! Haben and werden are irregular in both the present and past tenses.

The Past Tense of haben

The Past Tense of haben

| Person | Conjugation |

| First (sing.) | ich hatte |

| Second (sing.) | du hattest |

| Third (sing.) | er/sie/es hatte |

| First (pl.) | wir hatten |

| Second (pl.) | ihr hattet |

| Second (formal) | Sie hatten |

| Third (pl.) | sie hatten |

The Past Tense of werden

The Past Tense of werden

| Person | Conjugation |

| First (sing.) | ich wurde |

| Second (sing.) | du wurdest |

| Third (sing.) | er/sie/es wurde |

| First (pl.) | wir wurden |

| Second (pl.) | ihr wurdet |

| Second (formal) | Sie wurden |

| Third (pl.) | sie wurden |

Future Tense

Knowing the past tense is great for talking about things that have already happened. But what about the plans you’re making for next summer or even next weekend? In this section you’ll learn how to use the future tense. You’ll also learn how to use the imperative form of verbs to give commands. Ready? Go!

The future tense is so simple to use. You just use a present tense conjugation in the context of a future tense meaning.

Heute geht Karl in die Schule. (Karl’s going to school today.)

Heute geht Karl in die Schule. (Karl’s going to school today.)

Morgen geht Karl in die Schule. (Karl’s going to school tomorrow.)

Morgen geht Karl in die Schule. (Karl’s going to school tomorrow.)

But just as English has a more specific way of forming the future tense, so does German. Its formation is very much like English. In English you simply use the verb “shall” or “will” and follow it with the verb that describes what will be done in the future:

| I go there. | I shall go there. |

| You are late. | You will be late. |

| Mother has a problem. | Mother will have a problem.* |

Using

The other way to form the future tense is really quite simple. It has to do with another use of a verb you already know: werden. To form the future tense, conjugate werden and follow it by the infinitive that describes what will be done in the future. But be careful! In German the infinitive has to be the last word in the sentence—no matter how long the sentence might get. How about some examples?

Er wird nach Hause gehen. (He will go home.)

Er wird nach Hause gehen. (He will go home.)

Die Kinder werden morgen im Park spielen. (Tomorrow the children will play in the park.)

Die Kinder werden morgen im Park spielen. (Tomorrow the children will play in the park.)

Ich werde am Sonnabend in die Stadt fahren. (I will drive to the city on Saturday.)

Ich werde am Sonnabend in die Stadt fahren. (I will drive to the city on Saturday.)

*Did you notice that English has two tense forms for each tense? For each of those pairs, German always has only one tense.

Present, Past, and Future

You have already become acquainted with three important tenses in German. With these three you can speak about anything that has happened, that is happening, or that will happen.

There are three “signal” words that tell you what tense to use: heute (today), gestern (yesterday), and mor-gen (tomorrow). Heute is the signal for the present tense, gestern for the past tense, and morgen for the future tense. Let’s look at how the three tenses differ in form and meaning with regular verbs.

Contrasting the Present, Past, and Future Tenses

Contrasting the Present, Past, and Future Tenses

| Tense | English | German |

| Present | I am learning German. | Ich lerne Deutsch. |

| Present | I learn German. | Ich lerne Deutsch. |

| Past | I was learning German. | Ich lernte Deutsch. |

| Past | I learned German. | Ich lernte Deutsch. |

| Future | I will be learning German. | Ich werde Deutsch lernen. |

| Future | I will learn German. | Ich werde Deutsch lernen. |

Look at the sentences below and notice how the three tenses differ in verb formation and usage.

Present Heute bin ich in der Hauptstadt. (I am in the capital city today.)

Past Gestern war ich in der Hauptstadt. (I was in the capital city yesterday.)

Future Morgen werde ich in der Hauptstadt sein. (I will be in the capital city tomorrow.)

Future Tense with Irregular Verbs

Because in the future tense you use werden plus an infinitive, the irregular verbs are very easy to use in the future tense. There’s no stem change to remember. Remember that when you form the future tense of any verb, you conjugate werden and place the conjugated verb “as an infinitive” at the end of the sentence. That means that you have to change any irregularity in the present tense back to the verb’s infinitive form, when restating a sentence in the future tense.

Contrasting the Present and Future Tenses of Irregular Verbs

Contrasting the Present and Future Tenses of Irregular Verbs

| Present Tense | Future Tense |

| Er liest die Zeitung. (He reads the newspaper.) | Er wird die Zeitung lesen. (He will read the newspaper.) |

| Sie läuft in die Schule. (She runs to school.) | Sie wird in die Schule laufen. (She will run to school.) |

| Sabine trägt einen neuen Hut. (Sabine is wearing a new hat.) | Sabine wird einen neuen Hut tragen. (Sabine will wear a new hat.) |

| Das Kind spricht kein Deutsch. (The child doesn’t speak any German.) | Das Kind wird kein Deutsch sprechen. (The child will not speak any German.) |

| Andreas fängt den Ball. (Andreas catches the ball.) | Andreas wird den Ball fangen. (Andreas will catch the ball.) |

| Wo trifft sie die Touristen? (Where is she meeting the tourists?) | Wo wird sie die Touristen treffen? (Where will she meet the tourists?) |

Prefixes

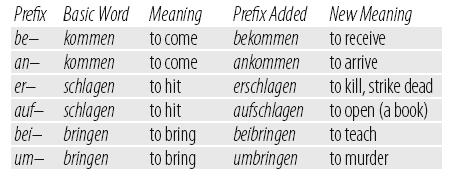

You probably have noticed by now that many German words appear with different prefixes. Those prefixes change the meaning of a word, but they don’t change how the basic word functions. For example, an irregular verb is still irregular no matter what the prefix might be.

Prefixes aren’t unique to German. There are many in English, and they alter the meaning of words just like German prefixes. In the following table, notice how the meaning of a word is changed by adding a prefix.

Prefixes with German Words

Prefixes with German Words

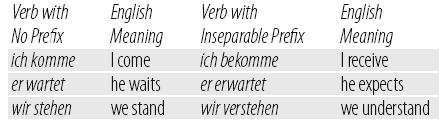

Inseparable Prefixes

The inseparable prefixes are: be–, ent–, emp–, er–, ge–, ver–, and zer–. Here are some verbs that have these prefixes: bekommen (to receive, get), entlassen (to set free, dismiss), empfinden (to perceive), erwarten (to expect), gehören (to belong to), verstehen (to understand), and zerbrechen (to break to pieces).

When these prefixes are attached to a word, the accent is always on the second syllable: besuchen (beh-ZOOCHen) (to visit), gebrauchen (geh-BROWCH-EN) (to use), verlachen (fair-LUCH-en) (to laugh at).

Conjugating Verbs with and Without Inseparable Prefixes

Conjugating Verbs with and Without Inseparable Prefixes

Separable Prefixes

Some of the primary separable prefixes are: an, auf, aus, bei, ein, her, hin, mit, nach, um, and weg. To conjugate a verb with a separable prefix, place the prefix at the end of the sentence and conjugate the verb normally. For example, the infinitive: ansehen (to look at) in the present tense:

Conjugating a Verb with a Separable Prefix

Conjugating a Verb with a Separable Prefix

Ich sehe . . . an.

Du siehst . . . an.

Er sieht . . . an.

Wir sehen . . . an.

Ihr seht . . . an.

Sie sehen . . . an.

Add the following words to your vocabulary and take careful note of how the prefixes change the meaning of the words.

hören (to hear)

hören (to hear)

aufhören (to stop, cease)

aufhören (to stop, cease)

nehmen (to take)

nehmen (to take)

stehen (to stand)

stehen (to stand)

verstehen (to understand)

verstehen (to understand)

Be savvy about prefixes. Always check out the prefix of a word before assuming what the word means. Although you know that stehen means “to stand,” that information can’t necessarily help you to know what entstehen means. (By the way, entstehen means “to originate.”) You know that nehmen means “to take.” But the meaning of the verb er nimmt . . . an and of the verb er nimmt . . . ab has been altered to “he assumes” and “he reduces.” Never underestimate the importance of the prefix.

Using German well means knowing prefixes and using them properly.

Direct Objects

To discover the direct object in a sentence, just ask “what” or “whom” with the verb. Examples:

Finding the Direct Object

Finding the Direct Object

| Sentence | What or Whom? | Direct Object |

| John buys a car. | What does John buy? | car |

| I like it. | What do I like? | it |

| She sent a long list of problems | What did she send? | list |

German is very similar to English in that some nouns—feminine and neuter nouns, specifically—don’t make any changes when they’re used as direct objects. And just like English, most German pronouns do require changes. Look at these examples:

German Nouns and Pronouns as Direct Objects

German Nouns and Pronouns as Direct Objects

| Noun as Subject | Noun as Direct Object |

| Die Schule ist in der Stadt. (The school is in the city.) | Sie (pl.) sehen die Schule. (They see the school.) |

| Die Lehrerin ist da. (The teacher is there.) | Sie (pl.) sehen die Lehrerin. (They see the teacher.) |

Pronoun as Subject | Pronoun as Direct Object |

| Ich bin in Berlin. (I am in Berlin.) | Sie (pl.) sehen mich. (They see me.) |

| Du bist in Hamburg. (You are in Hamburg.) | Sie (pl.) sehen dich. (They see you.) |

Nominative and Accusative

The nominative case is the name given to the subject of a sentence. The subject is said to be in the nominative case.

English: The boy is going to the park.

English: The boy is going to the park.

German: Der Junge geht zum Park.

German: Der Junge geht zum Park.

Direct objects are said to be in the accusative case.

English: My brother knows the teacher.

English: My brother knows the teacher.

German: Mein Bruder kennt den Lehrer.

German: Mein Bruder kennt den Lehrer.

Whenever you change a masculine noun from der Mann to den Mann, you have changed it from the nominative to the accusative case. And with feminine and neuter nouns, the nominative and accusative cases are identical. This is also true of plural nouns.

Mein Bruder kennt den Lehrer. (My brother knows the teacher.)

Mein Bruder kennt den Lehrer. (My brother knows the teacher.)

Mein Bruder kennt die Lehrer. (My brother knows the teachers.)

Mein Bruder kennt die Lehrer. (My brother knows the teachers.)

Definite and Indefinite Articles in the Accusative Case

Definite and Indefinite Articles in the Accusative Case

A verb that is often followed by a direct object is haben (to have). Look at these examples:

Sie (pl.) haben die Zeitung.

Sie (pl.) haben die Zeitung.

(They have the newspaper.)

Wir haben ein Problem. (We have a problem.)

Wir haben ein Problem. (We have a problem.)

Pronouns in the Accusative Case

Pronouns in the Accusative Case

Using Adjectives with Direct Objects

You learned that masculine nouns as direct objects change to the accusative case. That means that der Mann becomes den Mann. The same –en ending occurs when an adjective is added: der alte Mann becomes den alten Mann in the accusative case. Since the feminine, neuter, and plural are identical in both the nominative and accusative cases, there is no change in the adjective ending when they are used as direct objects.

Look at the pattern of adjective endings in the nominative and accusative cases.

Comparing the Nominative and Accusative Cases

Comparing the Nominative and Accusative Cases

Let’s look at some examples using adjectives with direct objects:

Der neue Schüler wohnt in Deutschland. (The new student lives in Germany.)

Der neue Schüler wohnt in Deutschland. (The new student lives in Germany.)

Wir besuchen den neuen Schüler. (We visit the new student.)

Wir besuchen den neuen Schüler. (We visit the new student.)

Die arme Frau kommt aus Österreich. (The poor woman comes from Austria.)

Die arme Frau kommt aus Österreich. (The poor woman comes from Austria.)

Hören Sie die arme Frau? (Do you hear the poor woman?)

Hören Sie die arme Frau? (Do you hear the poor woman?)

Prepositions That Take the Accusative

The accusative case is also required after certain prepositions

bis (to, till)

bis (to, till)

ohne (without)

ohne (without)

durch (through)

durch (through)

um (around, at)

um (around, at)

für (for)

für (for)

wider (against)

wider (against)

gegen (against)

gegen (against)

Accusative Case with Direct Objects and Prepositions

Accusative Case with Direct Objects and Prepositions

| Gender | Direct Object | Preposition |

| Masculine | Ich sehe den Mann. (I see the man.) | Es ist für den Mann. (It is for the man.) |

| Feminine | Ich sehe die Frau. (I see the woman.) | Es ist für die Frau. (It is for the woman.) |

| Neuter | Ich sehe das Kind. (I see the child.) | Es ist für das Kind. (It is for the child.) |

| Plural | Ich sehe die Kinder. (I see the children.) | Es ist für die Kinder. (It is for the children.) |

It works the same way with pronouns.

Accusative Pronouns with Prepositions

Accusative Pronouns with Prepositions

| Pronoun | Direct Object | Preposition |

| ich | Sie sehen mich. (They see me.) | Es ist für mich. (It’s for me.) |

| du | Sie sehen dich. (They see you.) | Es ist für dich. (It’s for you.) |

| er | Sie sehen ihn. (They see him.) | Es ist für ihn. (It’s for him.) |

| sie (sing.) | Sie sehen sie. (They see her.) | Es ist für sie. (It’s for her.) |

| wir | Sie sehen uns. (They see us.) | Es ist für uns. (It’s for us.) |

| ihr | Sie sehen euch. | Es ist für euch. |

| (They see you all.) | (It’s for you all.) | |

| Sie (formal) | Sie sehen Sie. (They see you.) | Es ist für Sie. (It’s for you.) |

| sie (pl.) | Sie sehen sie. (They see them.) | Es ist für sie. (It’s for them.) |

Indirect Objects

It may sound like just another confusing grammatical term, but an indirect object is something that you are already very familiar with. You use it every day in English. It’s really quite simple to identify in a sentence. Ask “for whom” or “to whom” something is being done and the answer is the indirect object. See the following for some examples in English:

Identifying Indirect Objects

Identifying Indirect Objects

| The Sentence Ask “for whom” or | “to whom” | The Indirect Object |

| He gave her a dollar. | To whom did he give a dollar? | her |

| We sent them a letter. | To whom did we send a letter? | them |

| I bought you a ring. | For whom did I buy a ring? | you |

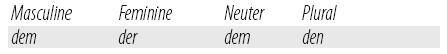

In German the indirect object is indicated by the dative case. Like the accusative case, this case requires changes to the definite and indefinite articles of nouns.

Definite Articles in the Dative Case

Definite Articles in the Dative Case

You’ll see that, unlike with the accusative case, which changed only masculine nouns, all nouns and pronouns make a slight change when used in the dative case. Masculine and neuter words change der and das to dem. Feminine nouns change die to der. And plural nouns change the article die to den.

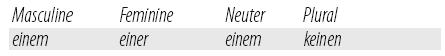

Indefinite articles also take different endings when they are used in the dative case.

Indefinite Articles in the Dative Case

Indefinite Articles in the Dative Case

In addition to these changes to the definite and indefinite articles, plural nouns also require an ending on the noun itself. In the dative plural the noun must end with an extra –n if there isn’t already one in the plural nominative: mit zwei Heften. Take a close look at the following examples to see how the dative endings are used in comparison with the nominative and accusative cases.

The Nominative, Accusative, and Dative Cases of Nouns

The Nominative, Accusative, and Dative Cases of Nouns

Let’s look at some sentences that demonstrate the use of the dative with an indirect object:

Die Männer geben der alten Frau ein Brötchen. (The men give the old lady a bread roll.)

Die Männer geben der alten Frau ein Brötchen. (The men give the old lady a bread roll.)

Der Vater kaufte seinem Sohn ein Fahrrad. (The father bought his son a bicycle.)

Der Vater kaufte seinem Sohn ein Fahrrad. (The father bought his son a bicycle.)

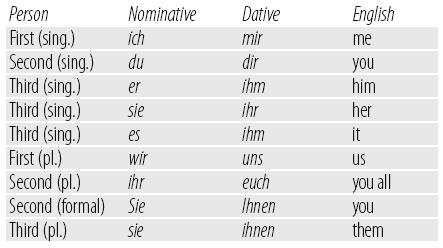

Changing Dative Nouns to Pronouns

You have already learned how to change nominative and accusative nouns to pronouns. The same idea is used when changing dative nouns to pronouns.

The key to making the change correctly is identifying the gender of the noun. If the noun is masculine or neuter, change to the pronoun ihm. If the noun is feminine, change to the pronoun ihr. And if the noun is plural, change to the pronoun ihnen. You already know that a noun combined with ich (mein Vater und ich) is replaced by wir. Therefore, if the noun/ich phrase is in the dative case, change it to the pronoun uns. Let’s look at some examples.

Pronouns in the Dative Case

Pronouns in the Dative Case

Notice that the dative forms of Sie and sie (pl.) are identical except for the capitalization of Sie and Ihnen.

Some example sentences with dative pronouns as indirect objects:

Er gibt ihm ein Geschenk. (He gives him a gift.) (To whom? Him.)

Er gibt ihm ein Geschenk. (He gives him a gift.) (To whom? Him.)

Wir kaufen ihr einen Hut. (We buy her a hat.) (For whom? Her.)

Wir kaufen ihr einen Hut. (We buy her a hat.) (For whom? Her.)

Dative nouns and pronouns also follow the dative prepositions: aus, außer, bei, gegenüber, mit, nach, seit, von, and zu (out, apart from, at, opposite, with, after, since, from, to).

Replacing Dative Nouns with Pronouns

Replacing Dative Nouns with Pronouns

| Noun in the Dative Case | Pronoun Replacement for the Dative Noun |

| Ich gebe dem Kind einen Bleistift. | Ich gebe ihm einen Bleistift. (I give him a pencil.) |

| Sie tanzt mit meinem Vater. | Sie tanzt mit ihm. (She is dancing with him.) |

| Mark wohnt bei seiner Tante. | Mark wohnt bei ihr. (Mark lives with her.) |

| Er kaufte den Kindern Schokolade. | Er kaufte ihnen Schokolade. (He bought them chocolate.) |

| Sie bekommt einen Brief von Hans und mir. | Sie bekommt einen Brief von uns. (She receives a letter from us.) |

Sentences Can Be Chock Full of Pronouns!

Have you noticed that sentences that contain an indirect object also have a direct object in them? Sie gibt ihrem Vater das Buch. (She gives her father the book.) To whom does she give the book? Ihrem Vater is the indirect object. What does she give to her father? Das Buch is the direct object.

You’ve practiced changing either the indirect object noun or the direct object noun to a pronoun. But it’s possible to change both to pronouns. You do it in English, but you may add a word when you do so. You place the preposition “to” or “for” in front of the pronoun that has replaced the indirect object. Look at these examples of changing both the direct object and indirect object nouns to pronouns:

Mary sent the man some sandwiches.

Mary sent the man some sandwiches.

Mary sent them to him.

We bought Sally a new toy.

We bought Sally a new toy.

We bought it for her.

German doesn’t have to add a preposition when changing indirect and direct object nouns to pronouns. But there is a little switch made: The indirect object pronoun changes position with the direct object pronoun. Take a look at some examples:

Ich gebe dem Mann eine Tasse. Ich gebe sie ihm.

Ich gebe dem Mann eine Tasse. Ich gebe sie ihm.

Erich kaufte seiner Schwester ein Fahrrad.

Erich kaufte seiner Schwester ein Fahrrad.

Erich kaufte es ihr.

Dative case nouns and pronouns are also used after the dative prepositions: aus, außer, bei, gegenüber, mit, nach, seit, von, and zu (out, apart from, at, opposite, with, after, since, from, to). For example: mit dem Mann (with the man), von ihr (from her).