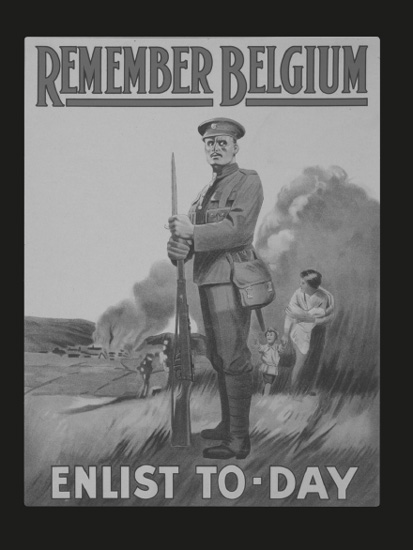

Germany invaded Belgium early in the war, violating its right to be neutral. Britain joined in Belgium’s defense, becoming one of the Allies. This 1915 British poster encourages men to sign up for the army in order to protect innocent Belgians, especially mothers and children.

“Heir to Austrian Throne Assassinated; Wife by His Side Also Shot to Death,” blazed the headline in the New York Tribune on June 29, 1914. “Bullets from a . . . revolver in the hands of [a] . . . youth riddled the heir apparent and his wife. . . . Another terrible chapter has thus been written into the tragic and romantic history of the House of Hapsburg [rulers of Austria-Hungary]. . . . The flying bullets struck [Franz] Ferdinand full in the face. . . . An instant later he . . . sank to the floor of the car in a heap.”

The nineteen-year-old assassin was Gavrilo Princip, one of a group of seven young men who planned to kill Franz Ferdinand. The shooting happened in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, but not the Bosnia on the map today. Bosnia in 1914 was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was a territory much larger than today’s Austria. The empire also included what is now Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia, and parts of Poland, Romania, Italy, and Ukraine. It ruled people speaking more than fifteen languages, including German, Hungarian, Czech, Polish, and Italian, as well as the southern Slavic languages. Each had some desire to be independent. There was a movement to unite all Slavic-speaking peoples within their own nation. This was a nationalist movement—supported by people who thought that those with the same language, culture, and history should be able to live in countries governed by themselves.

Princip and his partners were from Serbia, which at the time was a small, independent country whose people spoke a Slavic language. They wanted Bosnia to become part of Serbia. Serbia was a leader in the movement to free Slavic-speaking peoples from Austria-Hungary. Austria-Hungary, however, wanted to control Serbia, stop all nationalist dissent, and rule southeastern Europe. The assassination of Franz Ferdinand set the Austro-Hungarian Empire against Serbia. Many people believe this tense political situation was the start of World War I.

Did a war that came to involve the entire world—a war that involved armies from six continents—really start because one man was shot and killed? In fact, the countries of Europe had been rivals for hundreds of years. So when Princip attacked the Austro-Hungarian heir in Bosnia, there was already a long history of feuding and competition. Austria-Hungary wasn’t alone in wanting to hold more territory and have more power. Britain, France, Russia, and Prussia (which became part of Germany), as well as Austria-Hungary, fought wars against one another during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Russia fought Japan in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5, over control of land in China and Korea, and lost. Serbia was successful in two Balkan wars in southeastern Europe in 1912 and in 1913. (The “Balkans” is one name for the area in southeastern Europe that includes Serbia.) The first pushed the Turkish (Ottoman) Empire out of some of its European territory. In the second, Serbia defeated Bulgaria, a relatively large country that was a rival for Slavic control.

The shooting of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was the spark that set off World War I. Here he is shown with his wife, Sophie, killed at the same time, and their three children.

The boundaries and names of countries were continually changing during this period. Germany, for example, did not become the country known today as Germany until 1871, when the German-speaking region of Prussia united with other German-speaking states to its south. Prussia was already an organized, powerful state. After Germany formed, the country not only built up its military forces but also began claiming colonies in Africa and the Pacific Ocean region. These included Togoland (now Ghana and Togo), the Cameroons (now Nigeria and Cameroon), German East Africa (now Tanzania), and Papua New Guinea. Germany was becoming an imperialistic nation—one that sought control over other countries, through either political arrangements or force.

This map shows the countries of Europe as they were in 1914. Austria and Hungary are part of one empire. Serbia sits below it. Most of Poland and Ukraine are part of Russia.

Germany’s increasing power threatened Britain and France, already major imperialist countries. They had built up colonial empires of their own. Britain had control of countries around the world, including India, South Africa, and parts of China. Countries such as Canada and Australia governed themselves but continued to have close ties to Britain. They would provide military support if Britain ever went to war. France ruled colonies in Africa—including Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, the Ivory Coast, and Senegal—and also in Southeast Asia—Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Having colonies made a country more powerful. The colonies provided raw materials, trading partners, and land for immigrants from the home countries to settle and develop for farming and business. Colonies usually made the home countries richer.

In the early twentieth century, Britain had the largest empire and the largest navy in the world. The new Germany, itself an empire, challenged that supremacy. France had a long history of quarrels with Prussia and the other German territories. (In 1871, France lost a war to Prussia, which then took over parts of what had been French territory, Alsace and Lorraine. The French were still bitter about this loss in 1914.) Russia, which included what is now most of Poland, sat on Germany’s eastern border; it was also Germany’s rival in trying to influence the countries of eastern Europe. By the early twentieth century, Germany felt surrounded by potential enemies. (Britain did not border Germany on land but was superior on the seas off Germany’s coast, although Germany was rapidly building up its own navy.) Germany decided to become the ally of Austria-Hungary—many people in Austria-Hungary spoke German—to balance the power of the other European countries. By the time it joined forces with Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was fairly weak but still trying to control the different nationalities inside its borders. (Austria-Hungary did not have a colonial empire.)

The European countries signed treaties, some of them secret, agreeing to protect one another in case of war. By 1914, Russia had a treaty to defend Serbia. (Russians also spoke a Slavic language.) France had a defensive treaty with Russia and one with Britain. Britain had an agreement to defend Belgium, a small country that had stayed neutral through earlier wars. Austria-Hungary and Germany had a treaty to protect each other. Both countries had a treaty with Italy to protect them if they were attacked first; together the three formed what was known as “the Triple Alliance.” Finally, Japan had an agreement to support Britain in case of war.

Few people expected that all these different treaties would be called upon at the same time or that all these countries would find themselves at war. But even ordinary people could sense that something was changing. “Germany endeavored to act as mediator in the Austro-Russian conflict,” wrote the newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung on July 31, 1914. “In this effort she was supported by England, France, and Italy, because all these Powers, as is clearly shown by the attitude of their Governments and also by the expressions of public opinion, wished to avoid a great European war. But it appears that . . . we are at the beginning of that great European war of which there has been so much talk, but in which no one seriously believed until today.”

The American novelist Edith Wharton noted that “Paris went on steadily about her mid-summer business of feeding, dressing, and amusing the great army of tourists who were the only invaders she had seen for half a century. All the while, every one knew that other work was going on. . . . Paris counted the minutes till the evening papers came. They said little or nothing except what every one was already declaring. . . . ‘We don’t want war.’ . . . If diplomacy could still arrest the war, so much the better; no one in France wanted it. . . . But if war had to come, then the country, and every heart in it, was ready.”

Three weeks after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Austria-Hungary demanded justice from Serbia. Serbia actually agreed to most of Austria’s demands, but the empire declared war anyway on July 28, 1914. Like a tower of blocks falling one after another, the other countries followed.

Russia immediately began putting together a large army to aid Serbia and fight Austria-Hungary. On August 1, Germany (Austria-Hungary’s ally) declared war on Russia. Germany then declared war on France (Russia’s ally) on August 3. Later that same day, France declared war on Germany. On August 4, Germany marched into neutral Belgium on its way to Paris, pulling Britain into the war. Japan declared war on Germany on August 23. Austria-Hungary then declared war on Japan. Italy decided to stay neutral; this did not violate the country’s treaty with Germany and Austria-Hungary, because the Italian government believed that Austria-Hungary had started the war. Even though Austria-Hungary was the first to declare war, Germany—with more military power and ambition—became the main enemy for France, Britain, and Russia and, eventually, for the United States.

When Sarah MacNaughtan, a Scotswoman who would later be an aid worker in France, arrived in London toward the end of August, she wrote in her diary: “Hardly anyone believed in the possibility of war until they came back from their August . . . Holiday visits and found soldiers saying goodbye to their families at the [train] stations. And even then there was an air of unreality about everything. . . . We saw women waving handkerchiefs to the men who went away, and holding up their babies to railway carriage windows to be kissed. . . . We were breathless, not with fear, but with astonishment.”

Germany declared war on Russia on August 1, 1914, and war on France on August 3. Here hundreds of Germans cheer in front of the cathedral in Berlin when they hear the news.

People in the warring countries and observers like the United States expected the war to be a short one. Each side felt sure it would quickly win. In fact, everyone predicted that the soldiers would be home for Christmas. But instead, the war lasted from 1914 through 1918 and drew in countries around the world. Italy eventually joined on the side of the Allies—Britain, France, and Russia—in May 1915. Among the nations supporting the Allies were China, Greece, Portugal, Brazil, Guatemala, and Romania. Those who entered the war later on the side of the Allies were called “Associated powers.” Japan and Portugal, for example, were Associated powers. The United States was as well. It preferred to be an “associate” rather than one of the main Allied powers, so that it would be completely independent from the British, French, and Russian governments in making military and diplomatic decisions.

These soldiers from India, one of Britain’s colonies, fought with the British against the Germans. Both Britain and France used colonial troops in the war.

Britain and France brought in troops from their colonies and former colonies to fight the war. Troops that supported the British included Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, East Asian Indians, and South Africans. France had the help of troops from Senegal, Morocco, and its other African colonies. Not only did colonial troops fight in Europe, but the Allies fought Germany in Germany’s African colonies. Germany provided support for the Ottoman Empire, which had success in battles against the British in Egypt but never completely controlled the country. It lost German East Africa to the Allies, but German forces continued to fight in parts of Africa until the end of the war. Japan protected Allied trade routes in the western Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean from the German navy and took over German colonies in the Pacific and East Asia.

Countries fighting on the side of Germany and Austria-Hungary included Bulgaria and Turkey. Turkey was the center of the Ottoman Empire, with territory in parts of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. Germany, Austria-Hungary, and/or Turkey fought Russian, British, and French forces in several territories and countries, including Iran, Iraq, Egypt, Palestine (parts of which are now Israel or are occupied by Israel), Syria, and southeastern Europe.

In April 1917, the United States joined on the side of the Allies. Almost all of America’s fighting was in France, against the Germans. Americans fought Austria-Hungary only in support of Italy. The United States declared war on Austria-Hungary in December 1917, after that country had defeated the Italians at the Battle of Caporetto and Italy requested help from the Allies. The United States never declared war on the Ottoman Empire. American troops were also sent to Panama to protect the Panama Canal.

U.S. troops fought in Russia only after the Russian government was taken over by the Bolshevik party in the October Revolution of 1917, which led to the establishment of the Soviet Union. The Bolsheviks were communists who maintained that the people of a country should jointly own all property, such as farms and factories, and that they should share equally with one another. In practice, communist governments did not allow much dissent or disagreement. The other Allies did not welcome the idea of communism in their own countries. The United States, for example, did not recognize the Soviet Union until many years after the war had ended.

The Allies were left with a new problem, however, when the Bolsheviks quit their war against Germany, signing a peace treaty in March 1918. Since the Allies were not sure that Germany would honor this peace—especially since there were a lot of weapons supplied by the Allies still in Russian territory—several Allied Countries, including the United States, sent troops to Russia.

Looking back at all these events, we realize now that World War I was neither short nor simple. But even so, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated—even after war broke out between a few European countries in 1914—it would have been hard to imagine that over the next four years battles would rage in nearly every corner of the world.