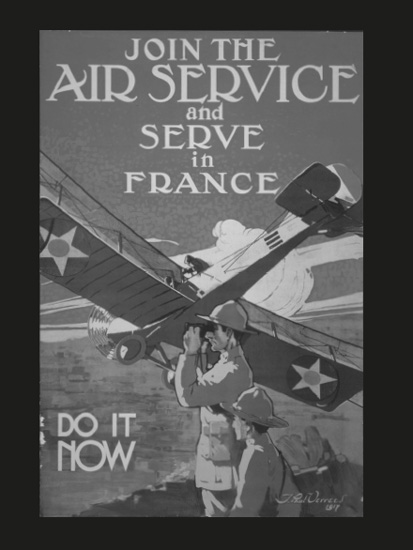

World War I was the first war where airplanes were used extensively. This 1917 poster urges Americans to join the air service. During the war, pilots and crew were part of the U.S. Army. A separate U.S. Air Force was not formed until 1947, after the Second World War.

Before World War I, battles had pitted soldier against soldier. Lines of infantry—soldiers on foot—from opposing sides would move toward each other. Armed with rifles, they would shoot an enemy or run him through with a bayonet. Cavalry—soldiers on horseback—would follow, their horses diving into combat with the enemy’s cavalry, swiping with swords and sabers to bring down the enemy’s horses and men. There were cannons and other artillery—large guns that stood in place, manned by more than one soldier—that fired from a distance. Their ammunition could kill several troops at a time or leave large holes in the ground. But most fighting was up close, man to man. Artillery was not powerful enough to wipe out assaults by hundreds of soldiers.

All that changed during the course of World War I. At the advent of the war, soldiers of the Allied Countries and Central Powers were still charging one another. But bigger and better weapons could shoot down many men before they could take on each other singly. “Those who knew the great [European] armies of the pre-war days would hardly recognize them now,” declared a 1917 article in Hearst’s Sunday American. “Everything has changed—uniforms, weapons, methods, tactics. Experience has shown that almost all our pre-conceived ideas were wrong. . . . Cavalry have played no role on the western front for nearly two years.” Older artillery—weapons such as cannons—used in the field had to be “reinforced by new giant artillery.”

The cavalry still used some horses, but horses were also important for other jobs. More reliable than vehicles for getting through mud, they hauled much of the war’s artillery. They transported supplies and carried the wounded. The British alone used half a million horses. Most of these were shipped from the United States, which sent 1,000 a day. Horses could be killed as easily as soldiers. At the Battle of Verdun in 1916, as many as 7,000 horses were killed in one day alone by French and German shells. Horses also died from harsh weather and working conditions.

But as Hearst’s Sunday American pointed out, it was not in the cavalry but “in the infantry . . . that you see the greatest changes. The average person’s idea of an infantry battalion is that of a thousand men armed with rifles and bayonets who have little to do on their own responsibility except to obey orders of their officers and carry a ghastly weight [of equipment] long distances on their backs. . . . Every infantryman is now a highly trained specialist who has a particular job to perform in attack and defense, and who requires at least a year’s hard training to perfect him.”

After the first few months of the war, soldiers began to spend much more time in the trenches than they did in direct attack. As harsh as life in the trenches was, they offered the best protection from the deadly weapons developed between 1914 and 1917, when the United States entered the war.

Once the pride of traditional armies, the cavalry became less important during World War I, although such units still existed. These British cavalrymen are passing through the ruined village of Caulaincourt on April 21, 1917. It was more common to use horses to transport weapons and supplies.

Field guns shot out millions of shells during the war. Bullets were solid metal; shells were hollow cylinders filled with various kinds of explosives that made a big impact on landing. They came in all sizes. During the first Battle of the Marne in 1914, French field guns fired shells three inches in diameter. A battery of field guns could cover ten acres of land in less than fifty seconds without approaching the enemy. In five days they had fired 432,000 shells.

Soldiers could tell when a shell was heading toward them. “There was a sound like the roar of an express train, coming nearer at tremendous speed with a loud singing, wailing noise,” an American Red Cross volunteer described the experience in 1916. “It kept coming and coming and I wondered when it would ever burst. Then when it seemed right on top of us, it did, with a shattering crash that made the earth tremble. It was terrible. The concussion felt like a blow in the face, the stomach and all over; it was like being struck unexpectedly by a huge wave in the ocean.” The Red Cross volunteer was not hurt, but the shell left a crater in the earth “as big as a small room.”

It was exactly this kind of fighting power—killing tens of thousands of men in the first weeks of the war—that led to trench warfare. On November 2, 1917, “[a]t three o’clock in the morning the Germans turned loose . . . several thousand shells,” recalled U.S. Corporal Frank Coffman. “[T]he only thing that prevented our platoon from being entirely wiped out was the fact that our trenches were deep, and the ground soft and muddy with no loose stones.” Nevertheless, the firing went on for forty-five minutes. Then the Germans fired above the frontline soldiers to keep support troops from advancing. “[T]wo hundred and forty [Germans] . . . hopped down on us,” continued Coffman. “They had crawled up to our [barbed] wire under cover of their barrage and the moment it lifted were right on top of us.”

Living with the sounds and vibrations of shells could cause “shell shock”—similar to what is now called “post-traumatic stress disorder” (PTSD). At first, this was thought to be caused by the physical force of the blast. Many of the victims, however, had no visible wounds. By 1917, doctors realized that shell shock was a breakdown of the mind caused by constant stress, even if the soldier was not physically injured. Harvey Cushing, a U.S. Army field surgeon, described one patient he met in France: “twenty-four years old, a clean-cut, fair-haired young fellow, of medium height and well built. . . . Apart from a couple of minor wounds (including burns from mustard gas) he was physically uninjured when he left the front . . . but he was suffering from severe visual and motor disturbance.”

American soldiers surround a 155mm field gun. It fired shells that are a little more than six inches in diameter, which are lined up next to the gun. Exploding shells made loud noises and caused vibrations. Soldiers exposed to many explosions sometimes developed “shell shock,” or post-traumatic stress disorder.

At the patient’s first “real battle” in July 1918, all the officers above him were killed or wounded. He was put in charge. He was told to take a town from the Germans. The town was won and lost nine times over the course of five days. He served as messenger and medical officer for his troops. Then he “was quite badly stunned by a high-explosive fragment which struck his helmet—like getting hit in the temple with a pitched baseball. . . . [He] was shaking and stammering and even found it difficult to sit down. . . . [He was] suffering from a severe headache, heard whistling in his ears, felt dizzy. . . . His memories became incoherent.” The patient wanted to go back to the front lines but couldn’t. Dr. Cushing diagnosed him as having “psychoneurosis in line of duty.”

Different versions of shell shock are now common in every war. During World War I the condition was treated with rest. Some shell shock victims were able to return to the front. Others did not recover quickly and needed extensive stays in psychiatric hospitals. Some did not recover at all.

Bullets fired from machine guns also terrorized World War I soldiers. Machine guns had been invented in the nineteenth century. A team of men, not an individual soldier, was needed to operate one. Because machine guns were heavy and difficult to move from place to place, they were not used a lot at the beginning of the war. But the Germans soon realized the guns would be excellent for defense, for cutting down rows of advancing soldiers. A soldier with a rifle could shoot fifteen accurate rounds of bullets a minute; a machine gun could shoot hundreds of rounds in the same amount of time. As the war progressed, machine guns on both sides became easier to use and more reliable.

U.S. Corporal Robert L. King was “assigned to a machine gun company. . . . We’ve been taught how to kill the Germans and we sure ought to get some of them with these machine guns for they shoot 600 times a minute. It takes two men to feed in the bullets, we are not supposed to get in the trenches with the infantry but [stay] slightly to the rear, for we shoot over the infantry’s heads. We are stationed at both ends of the trenches.”

Germans designed the first submachine gun that was easy to use. While the machine gun stayed in one location, the submachine gun could be carried by individual soldiers. It was able to fire multiple rounds per minute and had far more firepower than a rifle.

The automatic rifle, a weapon between the rifle and machine gun, was also faster to fire than a regular rifle. The French army used it to create “walking fire,” a line of soldiers marching forward and shooting at the enemy at the same time. The Americans introduced the Browning automatic rifle. The first shipment arrived in France in the summer of 1918. These rifles were “highly praised,” said a U.S. government report. They endured “hard usage, being on the front for days at a time in the rain and when the gunners had little opportunity to clean them, they invariably functioned well.”

Three soldiers of the 101st Field Artillery fire an antiaircraft machine gun at a German observation airplane. Ordinary rifles could shoot fifteen rounds of bullets a minute. A machine gun could shoot 600 rounds in that time.

Many of the weapons in World War I grew out of simpler versions from earlier times. Some form of hand grenade—basically an empty container filled with gun powder—had been used since the fifteenth century. The grenade might be filled with stones or metal. There was a fuse attached—a kind of string that could be lit with fire at one end. After a soldier lit the fuse, he threw it at the enemy. When the flame reached the end of the fuse, the grenade exploded. Flying metal parts or stones could wound and kill people. Hand grenades were dangerous to use, because they could go off accidentally. An English engineer invented a relatively safe grenade in 1915. It had a pin that was pulled for firing—a version of today’s grenades. It could also be aimed more accurately. Millions of these were used in World War I by both the Allies and the Germans. They were often dropped into trenches and were deadly to anyone near them when they exploded.

Flamethrowers—Flammenwerfers in German—also developed first in Germany. A version that could be carried like a backpack, with a hose for shooting out a stream of flammable liquid (such as gasoline), appeared in 1910. The German army first used flamethrowers in a battle in 1915. British Captain F. C. Hitchcock remembered, “The defenders of . . . [his] sector had lost few men from actual burns, but the demoralising element was very great. We were instructed to aim at those who carried the flame spraying device. . . . It was reported that a . . . [German with a flamethrower] hit by a bullet blew up with a colossal burst.” Eventually there were both knapsack flamethrowers and large ones fired from field artillery, which shot out containers filled with flaming fuel. The way to fight an attack, said Hitchcock, was to use “rapid fire and machine gun fire. As the flames shot forward, they created a smoke screen, so we realised we would have to fire ‘into the brown’ [smoke].”

The French army was the first to use gas—a form of tear gas—in August 1914. The German army next used it against the Russian army in January 1915. This was not deadly, but it irritated soldiers’ eyes. Cold weather made the gas less effective, so it did not have a big impact on the Russians, who were often battling in an icy environment. In April 1915, the Germans used chlorine gas against the Allies at the second battle of Ypres in Belgium. Canadian soldier A. T. Hunter saw a “queer greenish-yellow fog that seemed strangely out of place in the bright atmosphere of that clear April day.” The fog “paused, gathered itself like a wave and ponderously lapped over into the trenches. Then passive curiosity turned to active torment—a burning sensation in the head, red-hot needles in the lungs, the throat seized as by a strangler. Many fell and died on the spot.” Chlorine gas attacked the lungs so that soldiers could not breathe. Later, phosgene gas, which also damaged the lungs, was added to chlorine.

These soldiers are learning to use gas masks at a training camp at Fort Dix, New Jersey, before they are sent overseas. Gas masks could prevent troops from breathing in chlorine or phosgene gas that damaged lungs. But they could not protect against mustard gas, which passed through skin—and even through clothing and boots—into the body, affecting breathing and often causing temporary blindness.

The Allies too used gas as a weapon. The British used chlorine gas in September 1915 at the Battle of Loos in France. By 1918, 25 percent of the shells launched on the European front by both sides held some kind of gas. The Germans relied on gas the most. The French used about half of what the Germans did, and the British about one-third. Wearing a gas mask worked well to protect soldiers against chlorine and phosgene gas, and many styles were developed. Soon every soldier at the front carried one. There were also gas masks designed for horses and dogs. “Gas travels quickly, so you must not lose any time [putting on your mask]; you generally have about eighteen or twenty seconds in which to adjust your gas helmet,” wrote Arthur Empey, an American who joined the British army before the United States entered the war. “A gas helmet is made of cloth, treated with chemicals. There are two windows, or glass eyes . . . through which you can see. Inside there is a rubber-covered tube, which goes in the mouth. You breathe through your nose; the gas, passing through the cloth helmet, is neutralized by the action of the chemicals.”

This heavy British tank moves toward a bridge across the Somme River. The Somme Offensive, when French and British troops attacked German troops, began on July 1, 1916. It was one of the most deadly fights in any war. Tanks were not effective at the Somme, but they proved successful in later battles.

But gas masks did not offer protection against mustard gas, which was first used in 1917. Mustard gas could enter the body directly through exposed skin. It could even pass through clothes and heavy boots. Mustard gas dried out the tiny network of tubes in the lungs, making it painful to breathe. It caused blindness, vomiting, blisters, and bleeding. It actually caused relatively few deaths; only 2 to 3 percent of soldiers affected with mustard gas died. However, many were put out of action for days or weeks. While soldiers recovered from the symptoms of mustard gas, they could not fight.

Gas also frightened soldiers in a way that even the most dangerous artillery did not. Except for chlorine gas, it was invisible. Panic could spread if gas was in an area. Many soldiers complained of symptoms even though they had not actually been gassed. And all gases were dangerous weapons to use, even for the attacker. If the wind changed direction, they could affect one’s own soldiers, not the enemy. The Americans, who produced gas for the British and French, did not use much gas themselves, partly for that reason.

Tanks were another weapon introduced in World War I. They were basically farm tractors covered with iron to protect the soldiers inside as they moved across almost any kind of land—open, hilly, muddy, covered with trees or crisscrossed with barbed wire. They also drove over trenches and stopped machine-gun shells. But they were heavy, often weighing more than thirty tons, and they moved slowly—about two and a half to three and a half miles an hour, the speed of a brisk walk. American soldier George Noble Irwin left a memoir for his son describing what it was like to be in one. “Life in the Mark V [tank] was very unpleasant, the air contaminated from poorly ventilated gases of carbon monoxide and cordite fumes. Loud beyond belief with temperatures reaching 120 degrees. The crews wore helmets, and masks of chain mail to protect them from pieces of metal and rivets knocked loose from shells hitting the external armor.”

An American airplane is caught at the moment when its pilot is doing a loop in the air. This photograph shows how fragile early airplanes were. Yet Allied pilots were not allowed to use parachutes.

The British used tanks first, in 1916 at the Battle of the Somme. They started with forty-nine tanks. Seventeen broke down even before they got to the battlefield. Many of the ones left got stuck in muddy ground. “As we approached the Germans they let fire at us,” wrote British Lieutenant Basil Henriques, who was in one of the tanks. “At first no damage was done and we retaliated, killing about 20. Then a smash . . . caused splinters to come in and the blood to pour down my face. Another minute and my driver got the same. . . . Then another smash, I think it must have been a bomb. . . . The next one wounded my driver so badly that we had to stop. By this time I could see nothing at all.”

In the Battle of Cambrai in late 1917, tanks proved effective where the ground was firmer and the tank crews better trained. They managed to move five miles into German-held territory. “The English have brought in a new and terrible weapon,” wrote German teenager Elfriede Kuhr. “These armoured vehicles are called tanks. No one is safe from them: they roll over every artillery battery, every trench, every position, and flatten them—not to mention what they do to the soldiers. Anyone who tries to take shelter in a shell-hole no longer has a chance.” By 1918, the other Allies, including the Americans, were using tanks with success. The Germans never developed an effective tank of their own until after World War I, but they used captured British tanks to fight back.

World War I was the first war in which airplanes were used as weapons. The planes were relatively crude and hard to maneuver. At first they were used in place of hot-air balloons to observe the battlefield from above and report back on movements by the enemy. Airplane pilots not only had to observe field positions but also had to be on the lookout for enemy planes wanting to bring them down. Made of wood covered with canvas, the planes were easy to destroy. A plane would attempt to fly above an enemy plane and drop bricks to punch holes in its wings. Sometimes pilots used guns or grenades to bring the other plane down. The French were the first to fasten machine guns to airplanes.

Parachutes had been invented—soldiers in observation balloons wore them—but air pilots were not given them until 1918, and then only in Germany. Military leaders thought that having a parachute would make pilots more likely to bail out than engage in combat. The death rate among pilots was very high, for soon airplanes were not just used for spy missions. German and Allied pilots fought one-on-one with each other as well. These battles were called “dogfights,” and they required great skill. Many of the pilots died. The ones who succeeded again and again became famous worldwide. Pilots who shot down five planes were called “aces.” Perhaps the two most famous were Manfred von Richthofen—the German “Red Baron”—and the American Eddie Rickenbacker. “At 150 yards [from a German Pfalz plane] I pressed my triggers,” Rickenbacker wrote of one fight. “The tracer bullets cut a streak of living fire into the rear of the Pfalz tail. . . . The swerving of its course indicated that its rudder no longer was held by a directing hand. At 2,000 feet above the enemy’s lines I pulled up my headlong dive and watched the enemy machine continue on its course. . . . [T]he Pfalz circled a little to the south and the next minute crashed into the ground.”

But by 1916, solo airplane flights and dogfights were less common. Planes flew in groups or squadrons. They dropped bombs on trenches and cut down troops with machine-gun fire from the air. They also bombed enemy cities. On June 13, 1917, fourteen German planes dropped more than one hundred bombs on London, killing 162 civilians, the highest number of deaths in London during the war. German airplanes also bombed Paris. In the spring of 1918, the British and French began bombing German cities. Their main objective was to knock out German industries, but they also frightened civilians in places like Frankfurt and Mannheim.

German submarines proved dangerous to Allied ships throughout the war. This photograph captures the moment when the crew of German U-58 came out of their sub to surrender to the American destroyer USS Fanning on November 17, 1917. This was the first time in the war that an American ship captured a German vessel at sea.

Submarines—or U-boats—played a major part in the war at sea. The Allies had submarines, but the German subs that went after Allied merchant ships were the most famous and saw the most action. They sank some 5,000 merchant ships during the war. The convoy system helped greatly to protect Allied ships after 1917, but there were still losses.

Submarines were almost impossible to spot when submerged. The British developed a “hydrophone”—an underwater microphone to pick up sounds—but it was still difficult to locate the subs exactly. By the end of 1918, 178 U-boats had been sunk by the Allies, but Germany was quick to replace them with new ones.

Submarine crews lived in very tight quarters. Johannes Speiss, a German officer on a U-boat, explained that the watch officer’s “bunk was too small to permit him to lie on his back. He was forced to lie on one side and then, being wedged between the bulkhead to the right and the clothes-press on the left, to hold fast against the movements of the boat in a seaway.” The center of the sub “served as a passageway . . . [where] a folding table could be inserted. Two folding camp-chairs completed the furniture. While the . . . [officers] took their meals, men had to pass back and forth through the boat, and each time anyone passed the table had to be folded.” Inside the submarine was hotter than the sea, so drops of water formed on the steel structure. These drops fell onto the sleeping sailors. “Efforts were made to prevent this by covering the face with rain clothes or rubber sheets,” said Speiss. “It was in reality like a damp cellar.”

The countries that fought in World War I had a continual need for submarines and all the other ships, vehicles, and weapons necessary to fight. Many of these were made in Europe, but the United States, both before and after it became a combatant, remained a big provider. Producing weapons and food and encouraging civilian participation kept the American home front very busy during the war.