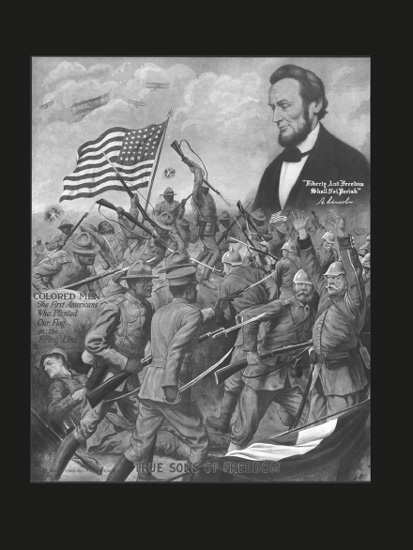

This 1918 poster celebrates contributions by African Americans to wars fought by the United States. It shows black doughboys attacking Germans, with President Abraham Lincoln in the upper right, to remind viewers of how black soldiers served valiantly during the Civil War.

At the end of April 1917, three weeks after the United States had declared war on Germany, a letter signed by “a Negro Educator” circulated through the small town of Friars Point, Mississippi. “Young negro men and boys what have we to fight for in this country?” it asked. “Nothing. Some of our well educated negroes are touring the country urging our young race to be killed up like sheep, for nothing. If we fight in this war time we fight for nothing. . . . [F]ight not for we will only be a . . . shield for the white race. After war we get nothing.”

African Americans in 1917 had few civil rights and were denied opportunities for education, decent housing, and jobs. Even if they did not live under segregation in the South—where, for example, they could not eat in “whites only” restaurants and had to sit at the back of streetcars—they suffered from discrimination. They were prevented from voting and often faced racial violence in riots and lynchings.

African Americans had every reason to question why blacks should fight to defend democracy in Europe when they lived as second-class citizens in the United States. But when war was declared, many volunteered to serve in the U.S. Army. At first, “Negro enlistment was discouraged,” wrote Emmett J. Scott, an African American and special assistant to the Secretary of War. The army, which had only a small number of black troops serving at the time, did not want more. Southern politicians expressed racist concerns if black men were drafted. That would result in “arrogant strutting representatives of the black soldiery in every community,” said Mississippi Senator James K. Vardaman. However, America’s military needed the manpower. Army leadership soon changed its mind. African Americans were drafted in large numbers, sometimes more than white men from the same towns and cities. White men were more likely to be exempted from service than black men. More than black men, white men had the kinds of skilled jobs in industry that allowed them exemptions. An estimated 370,000 African Americans served during World War I. They counted for 13 percent of the American military, while black people made up only about 10 percent of the U.S. population.

The majority of black Americans agreed with civil rights leader and editor W. E. B. Du Bois, who wrote, “Let us not hesitate. Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our white fellow citizens. . . . We make no ordinary sacrifice, but we make it gladly and willingly with our eyes lifted to the hills.” Leaders like Du Bois believed that by showing loyalty and patriotism, fighting in the war would put them in a better position to gain civil rights at home when it was over. Ellen Tarry of Alabama remembered supporting the war, but “though we carried huge signs in . . . a parade about fighting for democracy and how everybody should try to buy bonds, the Negro children were still put at the end of the procession.” Charles Brodnax, a black farmer from Virginia, simply “felt that I belonged to the Government of my country and should answer to the call and obey the orders in defense of Democracy.”

This African American man, in his doughboy uniform, served in the AEF in France. Even though the federal government did not want to recruit black soldiers when the war started, it finally drafted more than 300,000 men.

Horace Pippin served in the 369th Infantry, the famous black combat unit. These pages from the autobiography he wrote and illustrated after the war shows three soldiers marching. Although Pippin’s right hand was permanently injured, he became an extraordinary painter. Some of his work vividly portrays the African American experience of slavery and segregation.

Having volunteered or been drafted, a black soldier had few opportunities for advancement in the U.S. military. He served in segregated units, almost always under white officers. (There was one segregated training camp for a small number of black officers in Iowa, but none could rise above the rank of captain.) Many of the military training camps for black, as well as white, men were in the South. White Americans feared that letting black Americans use guns would increase their pride and literally put a weapon into their hands.

On August 23, 1917, black troops from a “colored” battalion—not draftees, but all experienced soldiers—attacked white civilians in Houston, Texas. The soldiers had finally found the segregation laws intolerable. They killed seventeen people. The battalion was put under arrest, more than one hundred of the men were court-martialed, and more than a dozen were executed. This incident actually halted the draft of African Americans until September 22, while the army worked out a way to train black troops quickly in camps close to their homes—in hopes of avoiding further conflict—and then send them to France. Another reason the U.S. Army sped up the process, even if the troops were undertrained, was because more manpower was needed. (Many white troops also received little training before they were shipped to France.)

Perhaps because of the fear of arming them, only 20 percent of black soldiers served in combat units. The vast majority were placed in labor battalions. They unloaded ships, built roads, dug trenches, constructed buildings, salvaged weapons and equipment, and performed other physically demanding jobs. It was similar to work they did in the United States and disappointed many black leaders, who had hoped the war would prove the fighting abilities and courage of black soldiers.

Horace Pippin, who later became a well-known and respected artist, wrote an autobiography of his experiences in World War I. “I remember the day very well, that we left the good old USA,” he wrote. “She was in trouble with Germany, and to do our duty . . . we had to go . . . and we did on the 17th of November 1917.” In France Pippin and his unit “laid about five hundred miles of rail . . . and we went to bed in the dark and got out in the dark, only the moon shone and did give us a little light. . . . We were in water up to our knees all the time. It was slow work and wet work, you would go to bed wet.”

Pippin did his share of labor, but he also served in combat with the 369th Infantry. The U.S. Army formed two black combat divisions, the 92nd and the 93rd. The 92nd Division was made up of men from several training camps who had not previously worked together. Training together made them more likely to know and understand what each one should do in battle. It also built up trust and comradeship between the officers and the soldiers. The 92nd Division did not do well in its first battles, but at the end of the war, through greater experience, its record improved. The 93rd Division, assembled from National Guardsmen (who already had training) and draftees from South Carolina, had an excellent record. They fought at the Meuse-Argonne and the Oise-Aisne in the summer and fall of 1918.

“I remember the first night that I put foot in No Man’s Land,” Pippin wrote. “It was the first time my company ever had any men in No Man’s Land.” He went on a scouting trip, creeping through wire into a shell hole. When he got back to his trench, “it was . . . raining, the water was dripping off of us. . . . We did not dare make a fire not even strike a match in the trench so it was not the first time I went to bed wet.”

Pippin fought in the Argonne Forest several times. At one point, the Germans “gave us shell fire, and the gas was thick, and the forest looked as if it were ready to give up all of its trees every time a shell came crashing through. . . . There was a big acorn tree that stood by my dugout, it was a fine one. But . . . the shell tore off the top of it. We hardly knew what to do, for we could not fight shells. But we could [fight] the Germans. We would rather for the Germans to come over the top than to have their shells.” Pippin was eventually shot and lost some of the use of his right arm, but it didn’t later stop him from painting.

Four of the 93rd’s regiments fought directly under French command. General Pershing advised the French officers commanding these black troops that they “must not eat with them, must not shake hands with them, seek to talk to them or to meet with them outside the requirements of military service. We must not commend too highly these troops, especially in front of white Americans.”

Here African American infantry troops are marching near Verdun, France. This photograph was taken on November 5, 1918, one week before the armistice.

Despite Pershing’s racist suggestions, the 93rd Division thrived. The most famous of its units was the 369th Infantry, the one in which Pippin served. Soldiers in the unit were called “the Harlem Hellfighters” because they came from the neighborhood of Harlem in New York City. These men spent 191 days at the front, longer than any other American regiment. As they marched toward the trenches for the first time, one black soldier remembered, “There were a whole lot of blind men, and one-legged men, and one-armed men, and sick men, all coming this way. I asked a white man where all these wounded men come from? And he says, ‘N_____r, they’re coming from right where you’re going the day after tomorrow.’”

The 369th arrived at Minacourt, France. Their white commander, Major Warner Ross, described the scene: “Stones, dirt, shrapnel, limbs and whole trees filled the air. The noise and concussion alone were enough to kill you. Flashes of fire, the metallic crack of high explosives, the awful explosions that dug holes fifteen and twenty feet in diameter. The utter and complete pandemonium and the stench of hell, your friends blown to bits, the pieces dropping near you.”

On May 15, 1918, two African Americans were on duty in the Argonne Forest. “While on night sentry duty, . . . [Pvt. Henry] Johnson and a fellow Soldier, Pvt. Needham Roberts, received a surprise attack by a German raiding party consisting of at least 12 soldiers,” stated an official U.S. government citation for bravery years later.

“While under intense enemy fire and despite receiving significant wounds, Johnson mounted a brave retaliation resulting in several enemy casualties. When his fellow Soldier was badly wounded, Johnson prevented him from being taken prisoner by German forces.

“Johnson exposed himself to grave danger by advancing from his position to engage an enemy soldier in hand-to-hand combat. Wielding only a knife and being seriously wounded, Johnson continued fighting, took his Bolo knife and stabbed it through an enemy soldier’s head.

“Displaying great courage, Johnson held back the enemy force until they retreated.”

These two African American soldiers received the French Croix de Guerre (Cross of War). By the end of the war, the entire 369th Infantry and two other black regiments were honored by the French with the Croix de Guerre for courage under fire. Pershing reversed himself after the war, stating, “I cannot commend too highly the spirit shown among the colored combat troops, who exhibit fine capacity for quick training and eagerness for the most dangerous work.” As for a reward from the United States, Henry Johnson, who died in 1929, received the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously (that is, after his death) in 2002. He finally received the United States’ highest honor, the Medal of Honor, in 2015.

Despite blatant discrimination, black Americans admirably served their country. Melville Miller, who was sixteen when he joined the army, recalled a march through parts of France that had once been held by the Germans. “That day, the sun was shining. . . . And the band was playing,” Miller said. “Everybody’s head [was] high, and we were all proud to be Americans, proud to be black, and proud to be in the 15th New York Infantry.”

At the same time African Americans were serving in France, those at home were going through major changes. After the economic recession of 1913, the war that started in Europe in 1914 created a demand for weapons, chemicals, metal products, and other materials needed by the Allies. But the war also diminished the wave of European immigrants who had been employed in large numbers in American factory and construction, as well as unskilled, work. Industries in the North had jobs to fill. Southern black Americans, tired of strict segregation and poverty, began to travel north and west to take advantage of the need for labor. “There is no advancement here for me,” decided an African American living in Texas in 1917. “I would like to come where I can better my condition[.] I want work and am not afraid to work. All I wish is a chance to make good.”

This porter, shown in 1917 with her supplies, cleaned the New York City subways. Although the majority of black people lived in the South, by 1914 many were heading north for jobs. Between 1914 and 1920, an estimated half a million African Americans moved to cities like New York, Chicago, and Detroit. This is known as “the Great Migration.”

“Because Negroes have made few public complaints about their condition in the South, the average white man has assumed that they are satisfied,” wrote African American W. T. B. Williams in a government report; “but there is a vast amount of dissatisfaction among them over their lot. . . . [T]he Negro’s list of grievances that have prepared him for this migration is a long one.”

Between 1914 and 1920, some half a million African Americans left the South, moving to cities including New York, Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Omaha. This was the beginning of what came to be known as “the Great Migration.”

This migration of blacks created opportunities for them but also considerable racial tension. They faced discrimination in housing, education, and the job market. They tended to live in informally segregated neighborhoods, in poor housing, some “that had no water and no toilets, whose roofs leaked and whose cellars were flooded,” reported one account in southeastern Pennsylvania. “Negroes were coming in a great dark tide from the South, and they had to have some place to live,” remembered poet Langston Hughes. “Sheds and garages and store fronts were turned into living quarters. As always, the white neighborhoods resented Negroes moving closer and closer. . . .”

Black workers were also called upon to work as strikebreakers, crossing picket lines to take the jobs of strikers. They did this because they were often desperate for work and not allowed into unions. But this angered white laborers. There were race riots, with whites attacking black people, including one in East St. Louis on July 7, 1917. Forty-seven people died, among them thirty-nine African Americans. Lynchings continued, especially in southern states, which were anxious about losing so much black labor. Eighty blacks were lynched in 1915, fifty-four in 1916, thirty-eight in 1917, and fifty-eight in 1918. President Wilson himself said that “lynching is unpatriotic,” but he also said that “the Federal Government has absolutely no jurisdiction over matters of this kind.” On top of everything else, the Wilson administration began to segregate employees in federal jobs, which were not segregated in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries. Some federal services were also segregated. Black people who wanted to mail letters now had to go to segregated windows in post offices, both in the South and the North.

Soldiers of the 369th Infantry, an African American combat regiment, arrive back in New York after their distinguished service in France. Known as “the Harlem Hellfighters”—Harlem is a traditionally black neighborhood in New York City—they were cheered by hundreds of thousands of black and white supporters in a victory parade on February 17, 1919.

Did African Americans do better in the United States because of the war? “Optimism as to the status of the Negro after the war is ill-timed,” wrote Chandler Owen, a black socialist, in March 1919. “Like all other people who have fought battles for their country, the Negro will have to return to engage in a political and industrial fight with his own country to secure his just rights. Not an inch or ell will be yielded except through compulsion and necessity. No one will say to the Negro, ‘you have fought so gallantly and vigorously, your loyalty was so unadulterated and true, you were so patriotic that we are going to give you the vote in the South . . . segregation in places of public accommodation will be made unlawful; lynching will be stopped by the stern arm of Government.’ . . . This indeed will not happen.”

Owen was right; it did not even begin to happen, at least not until the desegregation of the military in 1948 and the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In some ways, the situation was worse. As white men returned to civilian life, blacks lost their jobs. In 1919, several race riots broke out, in cities such as Chicago, Washington, Omaha, Charleston, and Knoxville. African Americans, including veterans of the war, continued to be lynched. But many blacks now lived permanently in the North, where, although they experienced discrimination, they were able to vote because there were no segregation laws or difficult registration tests to stop them, and they had a better chance of a good education. Organizations like the National Urban League, founded in 1910, helped them adapt to cities by finding them jobs and campaigning to open labor unions to African Americans. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, actively campaigned for black civil rights and would, in the 1930s, start a series of lawsuits against segregated education in the South. Gaining equality was a gradual process, and World War I did nothing major to advance it.

But the experience of being in France personally changed many African American soldiers even if it didn’t change the attitudes of white people. Bill Broonzy, a blues composer and singer, came home to Arkansas after serving in the war. “I had a nice uniform,” he commented. “I met a white fellow that was knowin’ me before I went into the army. So he told me, said, ‘Listen, boy,’ says, ‘Now you been to the army.’ I told him, ‘Yeah.’ He says, ‘How’d you like it?’ I said, ‘It’s OK.’ He says, ‘Well,’ he says, ‘you ain’t in the army now. . . . And those clothes you got there . . . you can take ’em home an’ get out of ’em an’ get you some overhalls [overalls]. . . . Because there’s no n_____r gonna walk around here with no Uncle Sam’s uniform on up and down the streets here.’”

Racist comments like that didn’t change the fact that black Americans had been treated well in France. “You know now that the mean, contemptible spirit of race prejudice that curses this land is not the spirit of other lands,” Reverend Francis J. Grimké said to black soldiers returning from Europe in 1919. “[Y]ou know now what it is to be treated as a man . . . to be treated like real American men.”

W. E. B. Du Bois summed it all up:

“We return.

“We return from fighting.

“We return fighting.

“Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France, and . . . we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.”