16

After the pool party, Teddy goes up to his bedroom for Quiet Time and I stay downstairs in the den. Maybe I don’t want to know what he’s doing up there. Maybe things will be better for me if I stop asking so many questions.

In the afternoon we take a long walk in the Enchanted Forest. We follow Yellow Brick Road to Dragon Pass and down to Royal River, and I try to spin a new story about Princess Mallory and Prince Teddy. But all Prince Teddy wants to discuss are spirit boards: Do they need batteries? How do they find the dead person? Can they find any dead person? Can they find Abraham Lincoln? I keep saying “I don’t know” and hope that he’ll lose interest. Instead he asks how much it costs to buy a spirit board, if it’s possible to make one.

Caroline gets home from work at her usual time and I hurry out for a long run, eager to get away and burn off stress. It’s nearly seven o’clock when I get home, and Ted and Caroline are waiting on my front porch. And as soon as I see their faces, I know that they know.

“Good workout?” Ted asks.

His tone is light, like he’s determined to keep things pleasant.

“Pretty good. Almost nine miles.”

“Nine miles, really? That’s remarkable.”

But Caroline has no interest in making small talk. “Do you have anything you want to tell us?”

I feel like I’ve been dragged into the principal’s office and forced to empty my pockets. All I can think to do is play dumb: “What’s wrong?”

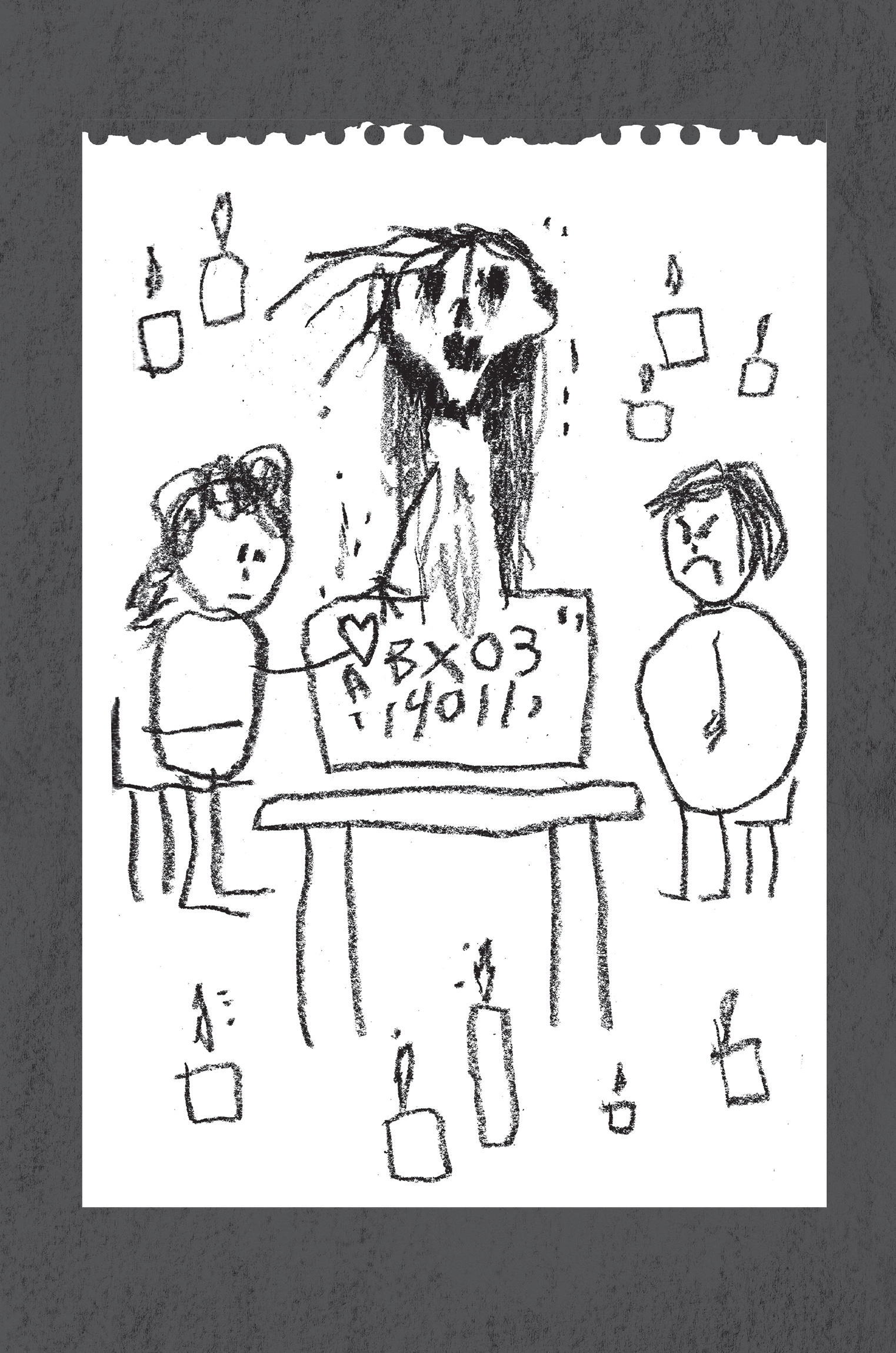

She pushes a sheet of paper into my hands. “I found this drawing before dinner. Teddy didn’t want to show me. He tried to hide it. But I insisted. Now you look at this picture and tell me why we shouldn’t fire you on the spot.”

Ted rests a hand on her arm. “Let’s not overreact.”

“Don’t patronize me, Ted. We’re paying Mallory to watch our child. And she left him with the gardener. So she could play Ouija board. With the pothead who lives next door. How am I overreacting?”

The drawing looks nothing like the dark sinister pictures that were left on my porch and refrigerator. It’s just a bunch of Teddy’s stick figure characters—me and an angry woman who’s obviously Mitzi, gathered around a rectangle covered in letters and numbers.

“I knew it!”

Caroline narrows her eyes. “Knew what?”

“Anya was here! At the séance! Mitzi accused me of pushing the pointer thing, but it was Anya! She was moving it. Teddy saw her. The picture proves it!”

Caroline is bewildered. She turns to Ted and he raises his hands, pleading with us to settle down. “Let’s all take a deep breath, okay? Let’s unpack what we’re hearing.”

But of course they’re confused. They haven’t seen everything I’ve seen. They’ll never believe me without seeing the pictures. I open the door to my cottage and urge them to follow me inside. I get out the stack of drawings and I arrange them on my bed in a grid. “Look at these. You recognize the paper, right? From Teddy’s sketch pads? Last Monday I found the first three drawings on my porch. I asked Teddy and he said he had nothing to do with them. The next night, I went out to dinner with Russell. The door to my cottage was locked. But when I came home, there were three more drawings on my refrigerator. So I hid a camera in Teddy’s bedroom—”

“You did what?” Caroline asks.

“A baby monitor. From your basement. I put the camera in his room during Quiet Time and I watched him draw.” I point to the next three pictures. “I watched him make these. He was using his right hand.”

Caroline shakes her head. “I’m sorry, Mallory, but we are talking about a five-year-old boy. We all agree that Teddy’s gifted but there’s no way he’s capable—”

“You’re not understanding me. Teddy didn’t draw these pictures. Anya did. The spirit of Annie Barrett. She’s visiting Teddy in his bedroom. She’s using him like a puppet. Somehow she’s controlling his body and she draws these pictures and she brings them to my cottage. Because she’s telling me something.”

“Mallory, slow down,” Ted says.

“We tried the séance so Anya would leave Teddy alone. I wanted to communicate with her. Directly. Keep Teddy out of it. But something went wrong. It didn’t work.”

I stop to pour myself a glass of water and gulp it down. “I know it sounds crazy. But all the proof you need is right here. Look at these pictures. They’re coming together, they’re telling a story. Help me make sense of it, please.”

Caroline sinks into a chair and buries her face in her hands. Ted manages to stay composed, like he’s determined to resolve the conversation. “We are committed to helping you, Mallory. I’m glad you’re being open and honest with us. But before we make sense of these pictures, we need to agree on a couple of facts, okay? And the biggest one is that ghosts don’t exist.”

“You can’t prove they don’t.”

“Because you can’t prove a negative! Look at the flip side, Mallory—you have no proof that the ghost of Annie Barrett is real.”

“These pictures are my proof! They’re on Teddy’s sketch pad paper. If he didn’t draw them—if Annie didn’t magically deliver them to my cottage—how did they get here?”

I see that Caroline’s attention has drifted to the small end table beside my bed, where I keep my phone, my tablet computer, my Bible—and the blank sketch pad that Teddy gave me a month ago, when I first started working for the Maxwells.

“Oh come on,” I tell her. “You think I’m drawing them?”

“I never said that,” Caroline says. But I can see her mind working, I can see she’s probing the theory.

After all: Wasn’t I prone to memory lapses?

Didn’t a box of Teddy’s pencils go missing last week?

“Let’s ask your son,” I tell them. “He won’t lie.”

It only takes a minute to cross the yard and get upstairs to Teddy’s bedroom. He’s already brushed his teeth and changed into his fire truck pajamas. He’s down on the floor next to his bed, building a Lincoln Log house and filling its bedrooms with plastic farm animals. We’ve never confronted him like this—all three of us entering his bedroom, amped up and stressed out. Immediately, he knows something is wrong.

Ted walks over to the bed and tousles his hair. “Hey, big guy.”

“We need to ask you something important,” Caroline says. “And we need you to answer with the truth.” She takes the pictures and fans them out on the floor. “Did you draw these?”

He shakes his head. “No.”

“He doesn’t remember drawing them,” I tell her. “Because he goes into a kind of trance. Like a twilight sleep.”

Caroline kneels beside her son and starts playing with a plastic goat, trying to keep the tone light. “Did Anya help you make these drawings? Did she tell you what to do?”

I’m staring at Teddy, trying to get him to make eye contact, but the kid won’t look at me. “I know Anya isn’t real,” he tells his parents. “Anya is just a make-believe friend. Anya could never draw real pictures.”

“Of course she couldn’t,” Caroline says. She puts her arm around his shoulder and squeezes him. “You are absolutely right, sweetie.”

And I start to feel like I’m going crazy. It’s like we’re all willfully ignoring the obvious, like we’ve all suddenly decided to agree that 2+2=5.

“But you all smell something in this bedroom, right? Look around you. The windows are open, the central air is running, his bedsheets are clean, I washed them today, I wash them every day, but there’s always a bad smell in here. Like sulphur, like ammonia.” Caroline shoots me a warning with her eyes but she’s missing the point. “It’s not Teddy’s fault! It’s Anya! It’s her scent! It’s the smell of rot, it’s—”

“Stop,” Ted tells me. “Just stop talking, okay? We understand you’re upset. We hear you, all right? But if we’re going to fix this problem, we need to deal with facts. Absolute truths. And I’m being honest with you, Mallory: I do not smell an odor in this room. I think Teddy’s bedroom smells perfectly fine.”

“Me, too,” Caroline says. “There’s nothing wrong with the way his bedroom smells.”

And now I’m certain I’m going crazy.

I feel like Teddy is my only hope but I still can’t get him to look at me. “Come on, Teddy, we talked about this. You know the smell, you told me it was Anya.”

He just shakes his head and bites his lower lip and suddenly he explodes into tears. “I know she’s not real,” he tells his mother. “I know she’s make-believe. I know she’s just pretend.”

Caroline puts her arm around him. “Of course you do,” she says, trying to comfort him, and then she turns to me. “I think you should go now.”

“Wait—”

“No. We’ve talked enough. Teddy needs to go to bed, and you need to go back to your cottage.”

And with all of Teddy’s tears, I realize she’s probably right, there’s nothing else I can do for him. I gather up the pictures and leave the bedroom and Ted follows me downstairs to the first floor.

“He’s lying to you,” I tell Ted. “He’s saying what you want to hear, so he doesn’t get into trouble. But he doesn’t believe it. He refused to look at me.”

“Maybe he was afraid to look at you,” Ted says. “Maybe he was afraid you’d get angry if he told the truth.”

“So what happens now? Are you and Caroline going to fire me?”

“No, Mallory, of course not. I think we just take the night to cool off. Try to clear our heads. Does that sound good?”

Does it? I don’t know. I don’t think I want to clear my head. I’m still convinced that I’m right and they’re wrong, that I’ve collected most of the puzzle pieces and now I just need to assemble them in the correct order.

Ted puts his arms around me.

“Listen, Mallory: You’re safe here. You’re not in any danger. I will never let anything bad happen to you.”

And I’m still sweaty from my run—I’m sure I smell terrible—but Ted pulls me closer and smooths the back of my hair with his hand. And in just a few moments it goes from comforting to weird; I can feel his warm breath tickling my neck, I can feel every inch of him pressing against me and I’m not sure how to break free of his grip.

But then Caroline comes stomping down the hallway. Ted springs away and I move in the opposite direction, slipping out the back door so I won’t have to see his wife again.

I don’t know what just happened but I think Ted is right.

Someone definitely needs a night to cool off.