5

My weekends are pretty quiet. Caroline and Ted will often plan a family activity—they’ll drive to the shore for a Beach Day, or they’ll take Teddy to a museum in the city. And they always invite me along but I never go, because I don’t want to intrude on their family time. Instead I’ll just putter around my cottage, trying to keep busy, because idle hands invite temptation, etc. On Saturday night, while millions of young people across America are drinking and flirting and laughing and making love, I’m kneeling in front of my toilet with a spray bottle of Clorox bleach, scrubbing the grout on my bathroom floor. Sundays aren’t much better. I’ve sampled all the local churches, but so far nothing’s clicking. I’m always the youngest person by twenty years, and I hate the way the other parishioners stare at me, like I’m some kind of zoological oddity.

Sometimes I’m tempted to go back on social media, to reactivate my accounts with Instagram and Facebook, but all my NA counselors have warned me to steer clear. They say these sites carry addiction risks of their own, that they wreak havoc on a young person’s self-esteem. So I try to keep busy with simple, real-world pleasures: running, cooking, taking a walk.

But I’m always happiest when the weekend is over and I can finally go back to work. Monday morning, I arrive at the main house and find Teddy down under the kitchen table, playing with plastic farm animals.

“Hey there, Teddy Bear! How are you?”

He holds up a plastic cow and mooooos.

“No kidding, you turned into a cow? Well, I guess I’m cow-sitting today! How exciting!”

Caroline darts through the kitchen, clutching her car keys and cell phone and several folders stuffed with papers. She asks if I can join her in the foyer for a minute. Once we’re a safe distance from Teddy she explains that he wet his bed and his sheets are in the washing machine. “Would you mind moving them into the dryer when they’re done? I already put new ones on his bed.”

“Sure. Is he all right?”

“He’s fine. Just embarrassed. It’s been happening a lot lately. The stress of the move.” She grabs her satchel from the hall closet and slings it over her shoulder. “Just don’t mention that I said anything. He doesn’t want you to know.”

“I won’t say a word.”

“Thank you, Mallory. You’re a lifesaver!”

Teddy’s favorite morning activity is exploring the “Enchanted Forest” at the edge of his family’s property. The trees form a dense canopy over our heads, so even on the warmest days it’s cooler in the woods. The trails are unmarked and unlabeled so we’ve invented our own names for them. Yellow Brick Road is the flat, hard-packed route that starts behind my cottage and runs parallel to all the houses on Edgewood Street. We follow it to a large gray boulder called Dragon’s Egg and then veer off onto Dragon’s Pass, a smaller trail that twists through a dense thicket of sticker bushes. We have to walk single file, with our hands outstretched, to keep from getting scratched. This path brings us down a valley to the Royal River (a fetid and slow-moving creek, barely waist deep) and Mossy Bridge, a long rotting tree trunk spanning the banks, covered with algae and weird mushrooms. We tiptoe across the log and follow the trail to the Giant Beanstalk—the tallest tree in the forest, with branches that touch the sky.

Or so Teddy likes to say. He spins elaborate stories as we hike along, narrating the adventures of Prince Teddy and Princess Mallory, brave siblings separated from the Royal Family and trying to find their way back home. Sometimes we’ll walk all morning without seeing a single person. Occasionally a dog walker or two. But rarely any kids, and I wonder if this is why Teddy likes it so much.

I don’t mention this theory to Caroline, however.

After two hours of stumbling around the woods, we’ve worked up an appetite for lunch, so we go back to the house and I make some grilled cheeses. Then Teddy goes upstairs for Quiet Time, and I remember that his bedsheets are still in the dryer, so I head upstairs to the laundry room.

On my way past Teddy’s room, I overhear him talking to himself. I stop and press my ear to his door, but I can only make out words and fragments. It’s like listening to one side of a telephone conversation where the other person is doing most of the talking. There are pauses between all his statements—some longer than others.

“Maybe? But I—”

“..….….…. .”

“I don’t know.”

“..….….…. .”

“Clouds? Like big? Puffy?”

“..….….….….….…. .”

“I’m sorry. I don’t under—”

“..….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….……”

“Stars? Okay, stars!”

“..….….….….….….….….……..….….….….….….……”

“Lots of stars, I got it.”

“..….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….……”

And I’m so curious, I’m tempted to knock—but then the house phone starts ringing, so I leave his door and hurry downstairs.

Ted and Caroline both have cell phones but they insist on keeping a landline for Teddy so he can dial 911 in case of an emergency. I answer, and the caller identifies herself as the principal of Spring Brook Elementary. “Is this Caroline Maxwell?”

I tell her I’m the babysitter and she stresses that it’s nothing urgent. She says she’s calling to personally welcome the Maxwells to the school system. “I like to talk with all the parents before opening day. They tend to have a lot of concerns.”

I take her name and number and promise to deliver the message to Caroline. A little while later, Teddy wanders into the kitchen with a new drawing. He places it facedown on the table and climbs up into a chair. “Can I have a green pepper?”

“Of course.”

Green bell peppers are Teddy’s favorite snack so Caroline purchases them by the dozen. I grab one from the refrigerator, rinse it under cold water, and carve out the stem. Next I slice off the top, creating a sort of ring, and slice the rest of the bell into bite-size strips.

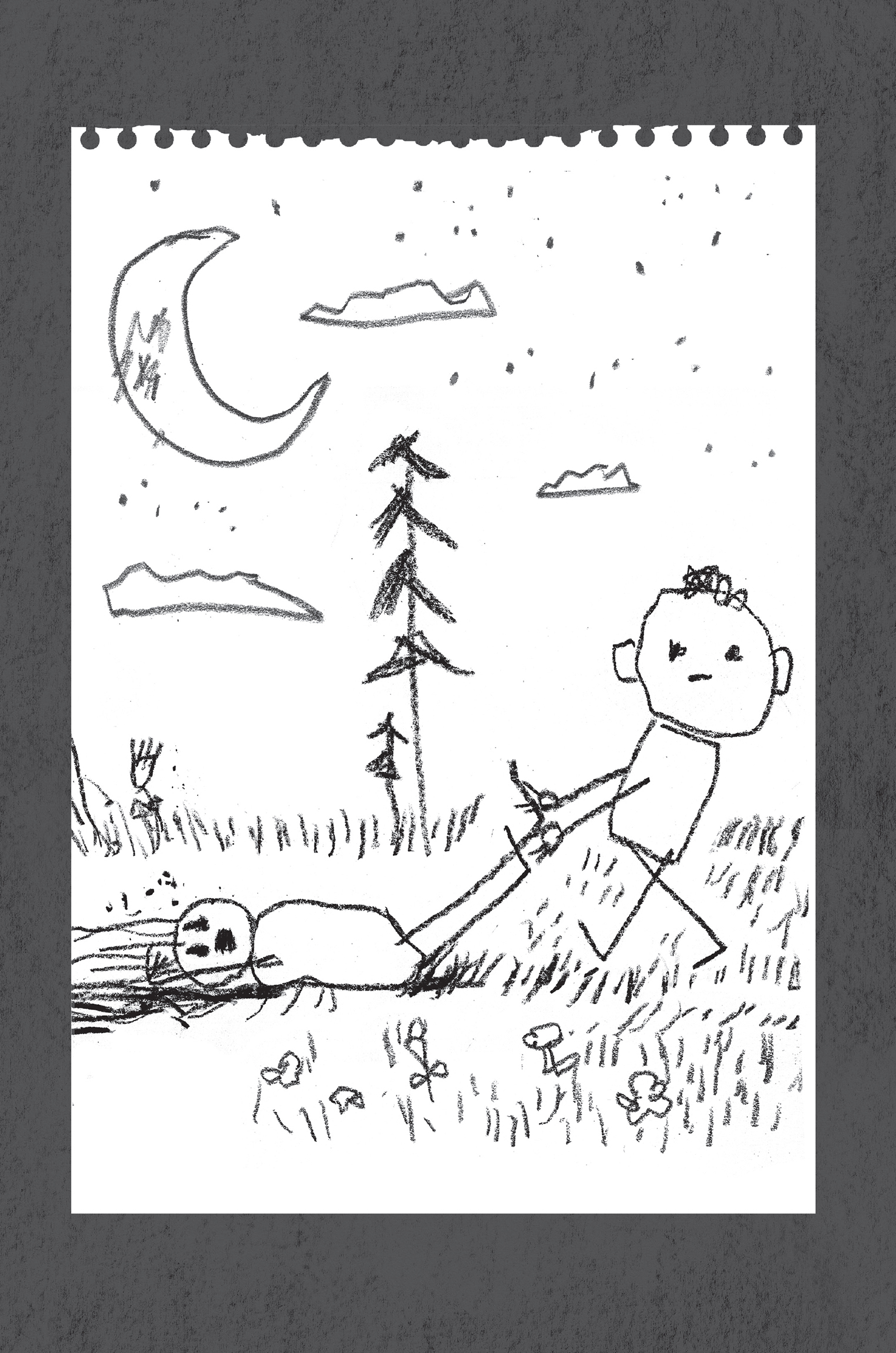

We’re sitting at the table and he’s happily munching on his pepper when I turn my attention to his latest illustration. It’s a picture of a man walking backward through a dense and tangled forest. He’s dragging a woman by the ankles, pulling her lifeless body across the ground. In the background, between the trees, there’s a crescent moon and many small twinkling stars.

“Teddy? What is this?”

He shrugs. “A game.”

“What kind of game?”

He bites into a strip of pepper and answers while chewing. “Anya acts out a story and I draw it.”

“Like Pictionary?”

Teddy snorts and sprays little flecks of green pepper all over the table. “Pictionary?!?” He flops back in his chair, laughing hysterically, and I grab a paper towel to wipe up the mess. “Anya can’t play Pictionary!”

I gently coax him to calm down and take a sip of water.

“Start over from the beginning,” I tell him, and I try to keep my tone light. I don’t want to sound like I’m freaking out. “Explain to me how the game works.”

“I told you, Mallory. Anya acts out the story and I have to draw it. That’s it. That’s the whole game.”

“So who is the man?”

“I don’t know.”

“Did the man hurt Anya?”

“How should I know? But it’s not Pictionary! Anya can’t play board games!”

And then he flops back in his chair again, caught up in another giggle fit, the kind of blissfully carefree laughter that only children can produce. It’s so joyous and genuine, I suppose it outweighs any concerns I might have. Clearly there’s nothing bothering Teddy. He seems as happy as any kid I’ve ever met. So he’s created a weird imaginary friend and they play weird imaginary games together—so what?

He’s still flailing around in his chair as I stand and carry the drawing across the kitchen. Caroline keeps a file folder in the bills drawer where she’s asked me to place Teddy’s artwork, so she can scan all the pictures into her computer.

But Teddy sees what I’m doing.

He stops giggling and shakes his head.

“That one’s not for Mommy or Daddy. Anya says she wants you to have it.”

I haven’t owned a computer since high school. For the past few years, I’ve been getting by with just a phone. But that night, I walk a mile to a shopping plaza and spend some of my paycheck on a new Android tablet. I’m back at the cottage by eight o’clock. I lock the door and change into my pajamas and then get into bed with my new toy. It only takes a few minutes to set up the tablet and connect to the Maxwells’ Wi-Fi network.

My search for “Annie Barrett” generates sixteen million results: wedding registries, architecture firms, Etsy shops, yoga tutorials, and dozens of LinkedIn profiles. I search again for “Annie Barrett + Spring Brook” and “Annie Barrett + Artist” and “Annie Barrett + dead + murdered” but none of these yield anything helpful. The internet has no record of her existence.

Outside, just over my head, something smacks against the window screen. I know it’s one of the fat brown moths that are all over the forest. They have the color and texture of tree bark, so they can easily camouflage themselves—but from my side of the window screen, all I see are their slimy segmented underbellies, three pairs of legs and two twitchy antennae. I rattle the screen and shake them loose, but they just fly around for a few seconds and come back. I worry they’ll find some gap in the screen and wriggle through, that they’ll migrate to my bedside lamp and swarm it.

Next to the lamp is my drawing of Anya being dragged through the forest. I wonder if I was wrong to keep it. Maybe I should have passed it to Caroline as soon as she walked through the door. Or better yet, I could have crumpled it into a ball and stuffed it into the recycling bin. I hate the way Teddy has drawn her hair, the obscene length of her long black tresses, dragged behind her body like entrails. Something on my nightstand shrieks and I spring out of bed before realizing it’s just my phone—an incoming call with my ringtone set to high.

“Quinn!” Russell says. “Am I calling too late?”

This is such a typical Russell question. It’s only eight forty-five, but he advocates that anyone serious about fitness should be in bed with the lights out by nine thirty.

“It’s fine,” I tell him. “What’s up?”

“I’m calling about your hamstring. The other day, you said you were tight.”

“It’s better now.”

“How far’d you go tonight?”

“Four miles. Thirty-one minutes.”

“You tired?”

“No, I’m fine.”

“You ready to push a little harder?”

I can’t stop staring at the drawing, at the tangle of black hair trailing behind the woman’s body.

What kind of kid draws this?

“Quinn?”

“Yeah—sorry.”

“Everything okay?”

I hear a mosquito whine and I slap the right side of my face, hard. Then I look at my palm, hoping to see mangled black ash, but my skin is clean.

“I’m fine. A little tired.”

“You just said you weren’t tired.”

And his voice shifts gears a tiny bit, like he’s suddenly aware there’s something going on.

“How’s the family treating you?”

“They’re fantastic.”

“And the kid? Tommy? Tony? Toby?”

“Teddy. He’s sweet. We’re having fun.”

For just a moment, I consider telling Russell about the situation with Anya, but I don’t know where to begin. If I come right out and tell him the truth, he’ll probably think I’m using again.

“Are you having glitches?” he asks.

“What kind of glitches?”

“Lapses in memory? Forgetfulness?”

“No, not that I can recall.”

“I’m serious, Quinn. It would be normal, under the circumstances. The stress of a new job, a new living situation.”

“My memory’s fine. I haven’t had those problems in a long time.”

“Good, good, good.” Now I hear him typing on his computer, keying in adjustments to my workout spreadsheet. “And the Maxwells have a swimming pool, right? You’re allowed to use it?”

“Of course.”

“Do you know the length? Ballpark?”

“Maybe thirty feet?”

“I’m emailing you some YouTube videos. They’re swimming exercises. Easy low-impact cross-training. Two or three times a week, all right?”

“Sure.”

There’s still something in my voice he doesn’t quite like. “And call me if you need anything, okay? I’m not in Canada. I’m forty minutes away.”

“Don’t worry, coach. I’m fine.”