Au Tombeau de Charles Fourier

I

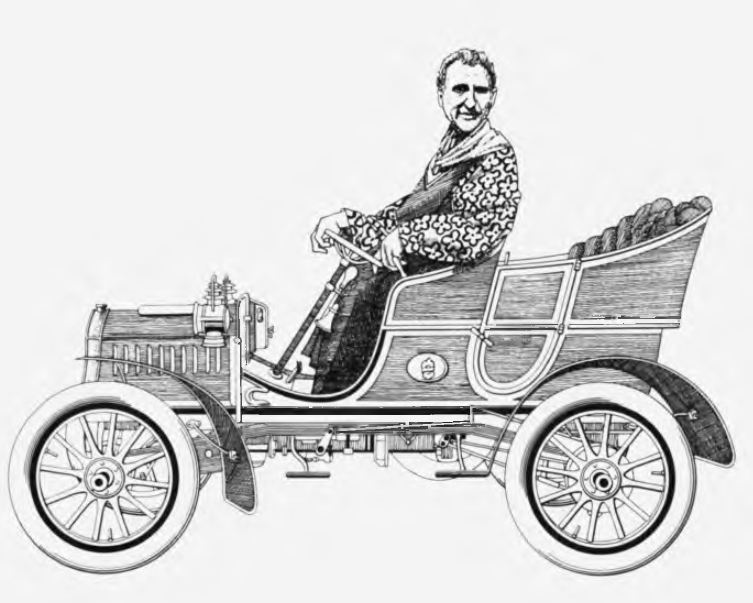

Here, chittering down the boulevard Raspail in her automobile, is Miss Gertrude Stein of Alleghany, Pennsylvania, a town she has no memory of at all and which no longer exists, and of Oakland, California, where as she will tell you, there is no there there.

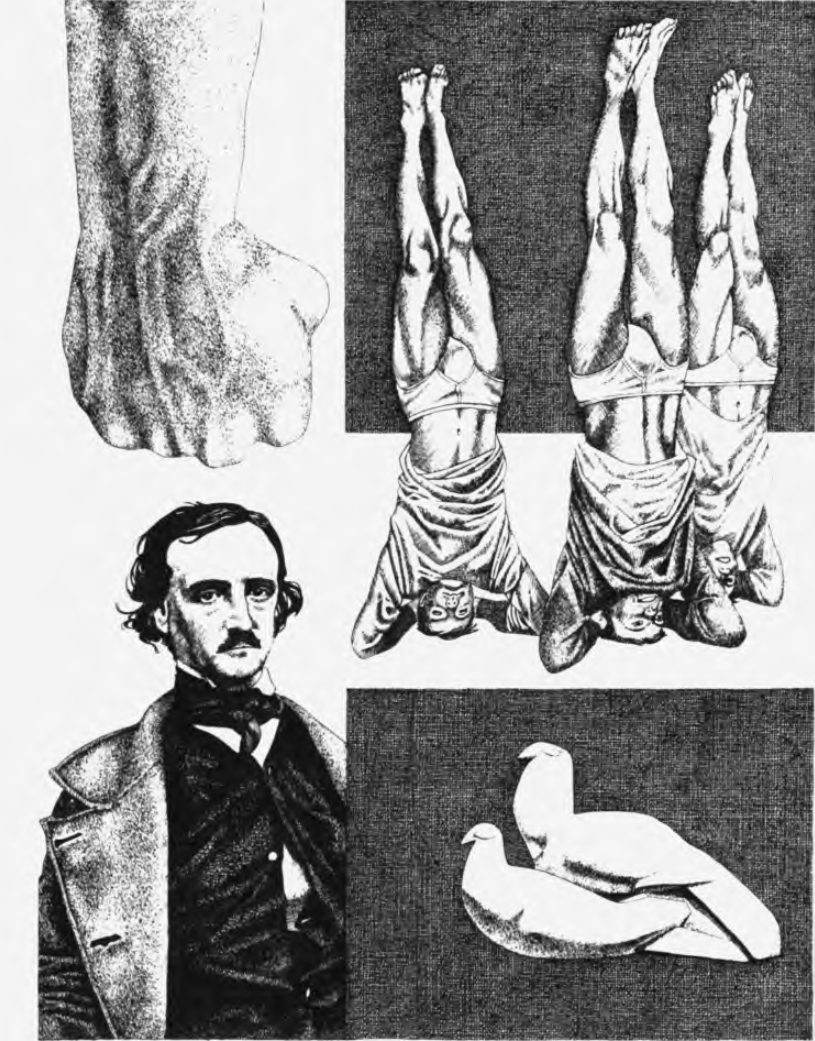

She has delivered babies in Baltimore tenements, dissected cadavers at The Johns Hopkins Medical School, and studied philosophy and psychology under William James at Harvard. She has cut her hair short to look like a Roman emperor and to be modern.

She has cut her hair short because behind her back Hemingway talked about her immigrant coiffure and steerage clothes and because Picasso had painted her portrait with her elbows on her knees in allusion to Degas’ Mary Cassatt sitting that way.

And what was there to do after that but to cut one’s hair, to end that chrysalis time. So many beginnings all her life made Gertrude Stein Gertrude Stein. She walked from the Luxembourg Gardens to the butte Montmarte to sit for Picasso and to be modern.

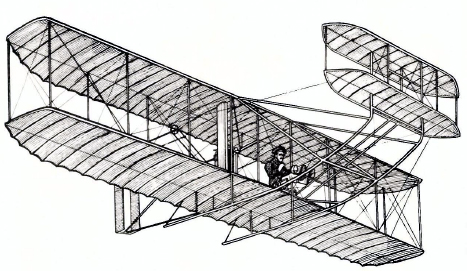

She has flown in an airplane since then and with her foot on the gas like Wilbur Wright flying at Le Mans and her Printemps scarf fluttering behind her like Blériot’s crossing the Sleeve, the Friedmann, the Clichy, the Raspail were hers, all hers.

She is driving home from reading The Katzenjammer Kids to Pablo. And The Toonerville Trolley and Krazy Kat. Genius is as wide as from here to yonder. Long ago, William James said in a lecture, the earth was thought to be an animal as yes it is.

Its skin is water, air, and rock. It is the horse, the wheel, and the wagon all in one. A single intelligence permeates its every part, from the waves of the ocean of light to the still hardnesss of coal and diamond deep down in the inmost dark.

In Professor James the nineteenth century had its great whoopee, saw all as the lyric prospect of a curve which we were about to take at full speed, but mistaking the wild synclitic headlong for propinquity to an ideal, we let the fire die in the engine.

And after dinner the Vanderbilts had the servants bring in baskets of Nymphenburg china which they smashed against the wall, cup by beautiful cup, for the fun of it. We let the fire die in the engine. Marguerites the meanwhile bloomed at Les Eyzies de Tayac.

II

And Elizabeth Gourley Flynn in shirtsleeves marched with the striking silk workers in Paterson. Between quiet and glory the usurers gobbling with three chins were spreading their immondices of bank money which is not money, no it is not money.

It is not the sou in the concierge’s fist nor the honest buck in the farmer’s. Between Picasso’s mandolin and pipe and Le Figaro bright on a tabletop they forced their muck of credit and interest, the business of business, not of things.

What could Rockefeller or Morgan care that the only time in history the command Beh-TELLion! Lee ye doon! was given was to the 96th Picton’s Gordon Highlanders at Quatre Bras when Wellington drove a charge of cavalry over their heads.

Alice in her ribbons! Alice in a kilt! C’était magnifique et c’etait la guerre. And down went the bagpipes missing never a skirl, and down went the black banners touching never a blade of Belgian grass and red coats and sabres flew over their heads.

The horses streamed over their heads even though they were advancing with bayonets en frise. Lord, what porridgy comments must have sizzled all burr and crack on what by fook the daff and thringing Sassenach duke thought the hoor’s piss he was doing.

Here she honked her klaxon at a moustached and top-hatted old type crossing the Raspail like a snail on glue, who cried out Espèce de pignouf! Depuis la Révolution les rues sont au peuple! Whereupon she honked back at him Shave and a haircut, two bits.

And Wellington’s cavalry flowed like so many Nijinskys over Wellington’s Highland Infantry and that was the glory that was fading from the world and all for money that is not money and Alice was waiting for her at home on the rue de Fleurus, next left.

Wasps fly backwards in figure eights from their paper nests memorizing with complex eye and simple brain the map of colors and fragrances by which they can know their way home again, in lefthand light that bounces through righthand light, crisscross.

The queen when she has chosen a site for a nest flies in wider eights than the cursory and efficiently warped ovals of scouts out to forage or the wiggly eights of trepidous adolescents on their timid first flight out from their hexagons shy but singing.

III

Ogo in his stringbean bonnet dances under the Sahara moon. That is not a sugarcane whistle we think he is playing. It’s his squeaky little voice so high, so high. He alone of all the creatures God made has no twin, none to trot by, none to nuzzle.

None that he can mount, now that time’s begun. The mud houses of Ogol in the rocky scrub country of the great Niger bend crowd their brown cubes under tall baobabs and cool acacias. Walls facing the trembling light of the Sahara are the color of pale biscuit.

The shadowed walls are the strong bister of red cattle. The square towers of the granaries rise higher than the houses. Ogotemmêli, the Dogon metaphysician, sits in his chicken yard, blind, telling of Ogo and Amma, his hands clasped behind his head.

He wears the oblong tabard of brown burlap which old men might wear in the freedom of the house. His grizzled beard is trimmed neat and close. He is teaching the clever frangi the history of the world, by command of the Hogon of Ogol.

He teaches him the structure and meaning of the world. The man Griaule, the frangi, who comes every year in his aliplani, sits before him. He makes marks along thin blue lines on pressed white pulpwood fiber finer than linen, putting a mark for every word.

Ogotemmêli touches the silver stylus with which Griaule makes the marks, runs his fingers over the thin leaves where the marks are put. The Hogon had decided: tell the white man who for fifteen years has come to Ogol asking, asking, tell him everything.

He already knows many things, the rites, the sacrifices, the order of the families, the great days. But never yet have they told him the inmost things, for fear that he would not understand. It was Ogotemmêli at the council who thought that he might understand.

He is like a ten-year-old child, but he is uncommonly bright, he had said to the Hogon. Might he not understand the system and the harmonies if they were explained to him slowly and carefully, as one instructs a boy? Besides, he gives our words to others.

The Hogon spoke with the Hogon of their brother people in the valley, who spoke with Hogons over near the sea, up and down the river, until it was decided that the white man was to know. So Ogotemmêli lights his pipe. Good thoughts come from tobacco.

IV

In the beginning, he said, there existed God and nothing. God, Amma, was rolled up in himself like an egg. He was amma talu gunnu, a tight knot of being. Nothing else was. Only Amma. He was a collarbone made of four collarbones and he was round.

You have heard the Dogon say: the four collarbones of Amma are rolled up together like a ball. Amma is the Hogon of order, the great spendthrift of being. He squanders all, generosity unlimited, and arranges what he squanders into an order, the world.

Amma plus one is fourteen. Say Amma and you have said space. For Amma to squander he needed space. He is space itself and only needed to move himself outward, to swell himself out, like light from the sun, like wind from the mountains, like thunder.

Three days after Picasso learned the word moose he was pronouncing it muse. It has a nose the likes of which you see on critics but the horns they have still verdaduramente the glory of God in them from the week of creation, a beast part hill, part tree.

You love all that’s primeval, Gertrude says, while I love all that’s newer than tomorrow. What is cubism but tilting our vision, ceasing to pretend that we see with our heads in a clamp? Each eye sees, that is Cézanne’s lesson, eyes move in looking, that is yours.

Matisse began to include the edges especially of women as they are seen a little more to the left than you would see if the right is there and a little more to the right than you would see if the left is here, a primitive and intelligent way of looking.

And then with Spanish generosity Pablo gives us more tilt of head everywhere, even in the middle of things, like Mercator’s map. She has told him with an earnestness that makes him whinny that if he were to fly he would see that the world is a cubist painting.

In an aeroplane? Braque and I wanted to build one, can you imagine? But only for a little while. We liked the shape, the circles of the wheels so balanced with the lines of the body. But no, Jertrude old girl, you’ll never get me up in one of those things.

An alcool framboise at the Closerie: the laughter of Apollinaire and Picasso, tears running down their cheeks, and Gertrude’s cackle right along with them, pounding each other’s backs, was there anything like it? One sees a lot of gypsies, the waiter said.

V

Of Diktynna not even the waff of a talus as she slips behind a sycamore, nor the rax of her talbots as they up and pad sprag after the crash of her toggery. Her cats, though, his cats are here, tabby and pied, get of the friends of the enemy of silver.

He lies under a slant stone bearing at its corners parabola, hyperbola, circle, ellipse. Bones, buttons, dust of flesh. High the jugal line would jut, and mortal holes gape where once there had been the iambus of his wink, a dust of flowers sifted through his ribs.

The fluid tongue is now trash. The bones of his thin fingers lie crossed over the immortally integral crocket of pubic hair, inert with silicon, gray and zinziber, mingled now with the rubble and pollen of his landlady’s hydrangeas and Charles Gide’s last roses.

La série distribue les harmonies, the stone reads. Les attractions sont proportionelles aux destinées. Elm leaves lie crisp and stricken upon the lettering. A porcelain wreath of some antiquity shares the moss and lichen that are claiming the slab.

ICI SONT DEPOSES LES RESTES

DE

CHARLES FOURIER

NE A BESANCON LE 7 AVRIL 1772

MORT A PARIS LE 10 OCTOBRE 1837

The series distributes the harmonies. Linnaeus died when he was six, Buffon when he was sixteen, Cuvier was his contemporary. Swedenborg died the week before he was born. All searched out the harmonies, the affinities, the kinship of the orders of nature.

All of nature is series and pivot, like Pythagoras’ numbers, like the transmutations of light. Give me a sparrow, he said, a leaf, a fish, a wasp, an ox, and I will show you the harmony of its place in its chord, the phrase, the movement, the concerto, the all.

The morning before we went to Fourier’s grave we watched President Giscard-d’Estaing walk from his inaugural up the Champs Elysées to the Arc, republican, pedestrian, affable. There was no La Marseillaise, no parade. Hatless he strode along alone.

But if it had been the month of Floréal in the Year 120, first pentatone of the Harmony, the sillima trees a water of hsiao chung and chinkled pyrite, we might have seen a scout of the Hordes and two little girls in Romany finery dancing with a ginger bear.

VI

The air rich with the peculiarly Parisian aroma of roasting chestnuts, quagga droppings, and baskets of marigolds, two little girls in Romany finery shimmy down the Elysées behind their elder brother tapping a timbrel above his head as he strides.

He twirls it high and brings it down with a clash and a hoodah! against the naked brown of his thigh. An elder recommends to his gaffers over their wine that they eye the nisser and the kobold, outriders as they read the emblems of the Chrysanthemum Horde.

They and the Goldenrods are of the Phalanstery Nora Joyce, them skirts as dazzled in the tuck and ruff as a margery prater all the colors of pepper from Floréal to Vendémiaire, Paraguay green, English blue, and a red to grace the boot of a Manchu khan.

Chilimindra and Gazella the girls, Crispin the brother, Strummel Jark the bear. Police of the Gardens and Corporals of Fine Tone salute as they pass, children all, clad by tribe, or naked except for the boondoggle of their clan and their doggy dignity.

Farther back, coming through the Arc, bouncing to drums, a zebra patrol enters the Elysées with a fanfare of E-flat trumpets. The colors out front are those of the XXI Hungarian Typhoons, Company Marie Laurencin, Magyar reds and pinks.

The guidons jig from under the arch, Phalanx Petulengro, Apollinaire, Souza Andrade, Marcel Griaule, Max de Bégouën. Chilimindra, Gazella, and Crispin, ten, eleven, and twelve, are champion makers of fudge, masters of zebras, of cobbling and of knots.

They are masters of horns and flowers, of printing and dancing, of the cello and cartography, of crystals and snakes, of polyhedral tensegrities and cetacean speech, of history and embroidery. They are companions palatine of the Great Bear of the Dnieper.

The circle on Fourier’s tomb means friendship, the hyperbola ambition, the ellipse love, the parabola family. The Little Hordes are two thirds boys and one third tomboys, the Little Bands are two thirds girls and one third shy mama’s boys.

Their mounts are zebras for the Hordes and quaggas for the Bands. The Grand Hordes, of Vestals in rawhide, prancing to trumpets, of naked Spartans with javelins and winebowl hairdos, of the Pioneers Major and Minor, are mounted all on tarpans.

VII

It was in Huffman’s Meadow out from Dayton on the way to Xenia that we mastered flying around a honey locust and Mr. Root the editor of Gleanings in Bee Culture saw us. We came through the film first in wild winds over the sands at Kill Devil Hill.

We came over the sands at Kitty Hawk, our huffer and zinger made of iron with feet that kicked in its heart where lightning burst the blood of blue grandfather scum rotted and gunked from the time of the chicken lizards. Our wings were made of cloth.

Our wings were made of splinters and knitten flax, our eyes were another’s and nothing was wholly right for shape or go. We could rock in rising and settling like a hornet, ride like a bee, but the figure eight of the wasp, or a clapfling proper, we could not do.

You cannot forage until you can twist your loop, shimmer of red on the up, shake of green on the down, with wood to chew on every bought, and a pear gone wine beyond the briars, and a liquor of roses sweet as wives drenching all, wind and light combing light.

Ogotemmêli lifted his head, cupping his hand behind his ear. There was something interesting in the air. Dougodyé, he said. I hear the step of Dougodyé. A young shepherd approached in sunglasses, a French undershirt, and wide baggy Dogan trousers.

Innekouzou’s cow, he said with a grin, has thrown twin calves. Give me a sou. Amma numo, said Ogotemmêli, vira aduno vo vaniemu! Come, Brother Griollu, lead me to the baobab, where we can drink beer for the blessed ancestors. Twin calves, I’ll be bound!

We must go honor the sign of twins, a blessing that refreshes me to hear. He went into his house with blind caution and came back in his Phrygian cap, his checkerboard tabard of goat’s wool, and a sou for Dougodyé. The armpit drums and Ogo fife had begun.

They walked between granaries and houses, by altars, to the great baobab. Everything that reaches up to God must be firmly rooted, Ogotemmêli said, bowing to the bows which he knew were being made to his rank, his blind steps sure. Twin calves!

A woman with many beads of cowries and beaten gold nummo put a gourd of cool beer into his long fingers. Elders with staves came gravely to the tree, talking of other twins in other days, holding cups to the calabash. This too, said Ogotemmêli, is worship.

VIII

Quagga, brother of the Herero and Himba, ran in gray herds silver through the mimosa. The mares pranced out before, smelling for lioness, foals and yearlings swirled girlishly behind, and the stallions, maned and haughty, confidently trotted at the rear.

Orangutans furiously pulled grass and put it on their heads as the quaggas streamed by. O moon, cried the orangutans, O moon. Elephants rolled their trunks, by which they meant that you never go to the waterhole except to find there a family of nickering quaggas.

They come to the water as picky as antelopes, their honest eyes looking at everything, their nostrils atick with the dusty smell of elephant, green fragrance of water, blunt odor of rhinoceros, the far stink of panther and the carrion cough of hyena.

Stepping to trumpet and snare they were to have been the mounts for patrols foraging for virtue from phalanx to phalanx, galloping out under banners citron and blue, captained by ten-year-olds, Bears of Artemis braceleted with silver snakes.

She rides, this Jeanne or Louise, with the poise of an Iroquois and the hauteur of a Cherokee. She wears, transactu tempore, like her flowery troop, braccae phrygiae, persimmon trousers open on a dapper bias from hip to inner thigh, tucked into canvas boots.

She wears, like the boys, a buttonless vest embroidered with frets and florets, a neckerchief as yellow as the Icelandic buttercup, and a tam sporting the gray and white ribbons of the Phalanx Jules Laforgue, Escadrille Orage XI, Grammarian First Class.

They are off, quaggas, girls, boys, and a shuffle of forty raccoons kept in pod by Weimaraner corporals. Of going a progress the raccoons understand nothing, but Weimaraners trained to shepherd raccoons on marches between phalanxes they understand.

The Weimaraners understand the Little Hordes, Quagga masters and spadgers after Harmonian honor, gosling cadets in the affinities, the gammes, who are out to gather optima, centibonum by centibonum, pips and stars and blue ribbons and duck feathers.

For getting the raccoons from phalanx to phalanx hale and chipper, five centibona. For taking over the chores of the local goslings, fifteen. For general good nature, judged by the Police of Tone and Manners, twenty. For coining a new word, twenty-five.

IX

For spending the day with an elder and looking intelligently at everything shown and listening with full attention to everything told, ten centibona. And then there were the decorations differing from phalanx to phalanx given for the fun of distinctions.

These were in millicupidon points convertible through Common Measure into centibona, called mush in Horde argot, for freckles, bluest eyes, messiest hair, dirtiest feet, mentula longissima, silliest giggle, slyest wink, grubbiest fingernails, charm.

Goldenest smile, earliest pubic hair, nautch in the innominata, largest number of warts, longest period between the frumps, slickest kiss, keenest whistle, worst joke, roundest behind, highest pisser, brightest glow from a dandelion under the chin.

A wark in the gaster, a curr in the jaws, and she flies in a figure eight. She bounces in the air, trig of girth and smelling of ginger-flower wax, of apples, of vespa. She thirls her wings, clapfling and brake flip, shimmering her neb. She dips.

He zips in for a squinny, mucin in his ringent jaws, buzzing. She hums. He rimples his golden crissum, sprag for a hump. He brushes her antennae with his forelegs, she his. They dance, a jig, insect of ictus, in linked orbits, more wiggle than step.

Zizz! She pounces, lifts him with all her legs, and flies up. He dangles, wings closed over feet. Over the rose she carries him, through the liliodendron, between the zinnias and sage, peonies, hollyhocks and comfrey, color milling in a quick of sugar.

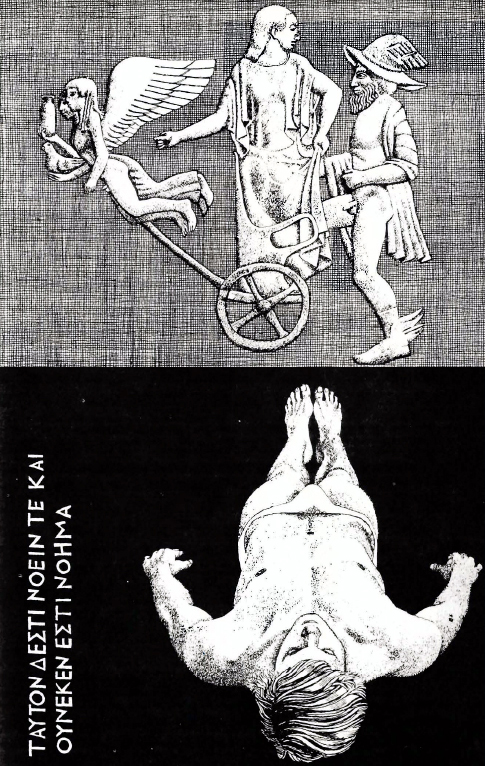

Amma drew a plan of the world before he created it. He drew the world in water upon the emptiness of space. To draw the egg of Amma you draw a long table of signs and you call this the stomach of all that is. Put a navel at the center. One dot starts all.

Divide the table into quarters, north east south west. Divide each quarter into sixty-four parts. Count them: you have two hundred and fifty-six parts. Add two numbers for each crossline that first divided the table into quarters, and two for the navel.

These are the two hundred and sixty-six things out of which Amma made the world. The quarters are earth, fire, water, air. The crosslines are the bummo giri, the eye lines. Four pairs of signs in the quarters are masters of all the other signs of Amma.

X

What works in the angle succeeds in the arc and holds in the chord.

XI

At the Casa da Vinci you could see an owl from Germany, a book of drawings showing the inside of the body, bowels, lungs, a baby in the womb, muscles knit around joints and stretched from bone to bone, a bat, thunderstones, and an egg of the ostrich bird.

You could see the imp Salai, so accomplished a rogue at ten that you could picture his neck in a noose by twenty. Marco had gone at him with a knife and had been thrashed for it by Ser Leonardo himself, who rarely lifted an angry hand. But for Salai, O già.

Salai was beautiful. Ser Leonardo was said to be the handsomest man in all Tuscany. Sono belli tutti i bastardi! Gian Antonio, as good-natured as a puppy, had been the favorite before Salai, and therefore undertook to deprave him properly and for good.

To discover that he himself was not half as depraved as he thought he was. Human nature, Leonardo said, spreading his hands, is varied. Talents are to be nurtured. Genius in the young is as yet mere energy. Gluttony matures into taste, lust into love.

The pinnace of the Santa Maria bore upon Guanahanì on the other side of the world, its banner of Leon and Castille and standard of the Admiral of the Ocean Sea moving in a tossing majesty through strange, crying, wheeling seabirds, fowl of Cathay.

Trumpets, drums, fifes, tabors and pipes sounded a music appropriate to an arrival in China from all the way around the world, a pomp for the procession of dukes toward the queen. The cross was held high on the prow, in triumph, before the scarlet flags.

A little boy the meanwhile in Firenze was drawing a bicycle. He begins with the wheels, turning a compass inexpertly: they are not quite round. Then, with a brown crayon, he draws the spokes, frame, handlebars, seat, sprocket, chain, pedals.

The chain is exactly the same kind as we use now, but Salai does not understand in the drawing he is copying how it is to work. Ser Leonardo’s drawing has hachures and fine lines too hard to make. He turns to something easier to draw, a pizzle.

By putting fowl’s legs to the balls, he achieves an uccello, a bird. He draws another, that smells the rump of the first, as with dogs. He smiles. He laughs. He calls Gian Antonio to come see. Perche l’uccello di Gian Antonio pende a metà agli sui ginocchi.

XII

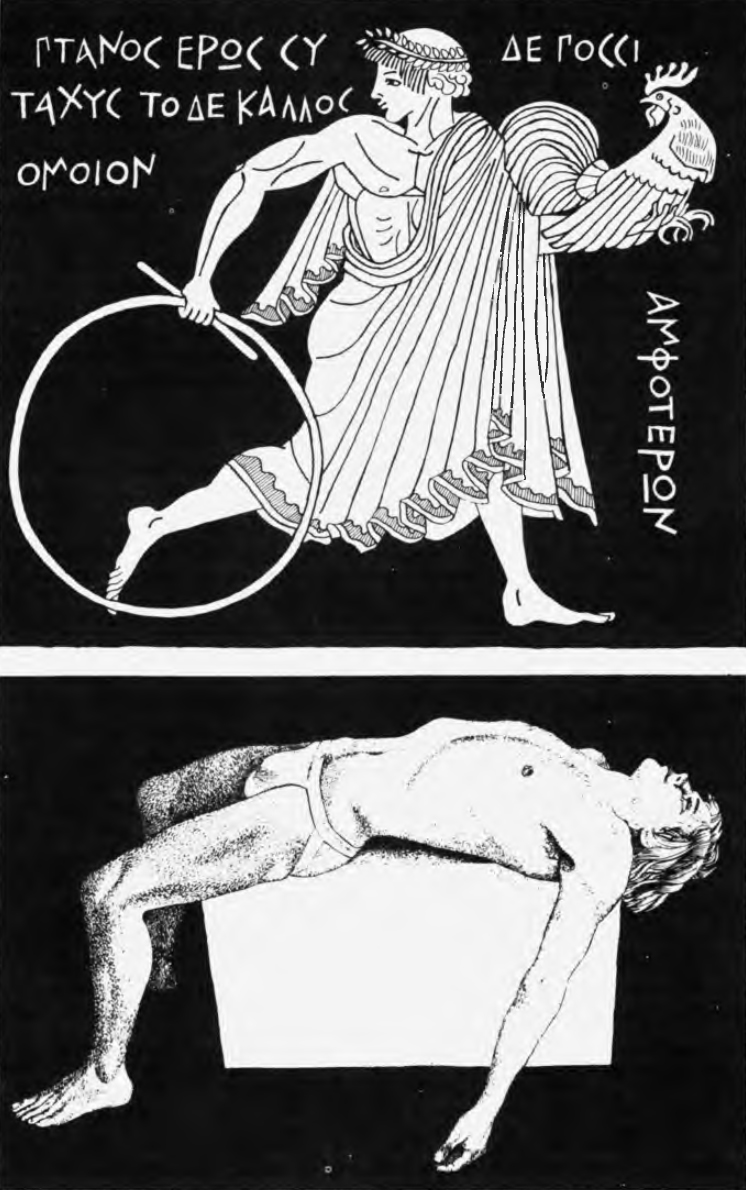

The Greeks called these winged phalloi that Salai drew by the bicycle pteroi, seeing the word eros in pteros, wing. Such poultry are scrawled everywhere in Mediterranean cities, in the sporting houses of Pompeii, the yellow walls of Naples, on Venetian doors.

You could see the design on Corinthian vases in the time of Paul, on bedside lamps in the days of Jonah, and the Florentines still call their members uccelli. Gian Antonio took the crayon and drew a supercilious, spoiled face on the page.

He added frogs and points to show that he meant Salai, whose jacket was so decorated. Now, he said, there are three pricks on this page. See the real thing, said Salai. Wait till I get the magnifying glass, and what’s this thing with two wheels, pig?

Scrotum of the Pope! Look what you’re drawing on. On the other side of the sheet was a round city with concentric walls, towers, galleries, roofed concourses, the kind of thing the maestro was forever drawing, whatever the eye of a strega they were.

The four pairs of signs which we make in the quarters are the masters of all the others, the Hogon signs. The other signs are of the world. All of this is Amma invisible. The signs are of women and rain and calabashes and antelopes and okra.

They are of things we can see and feel. But inside them all, inside everything, is the great collarbone. Amma is the inside of everything. The world is God’s twin. Amma and his world are twins. Or will be, when there is a stop to the mischief of Ogo.

These signs are bummo. Two of them, masters of all the rest, belong forever to Amma. The other signs are two hundred and sixty-four. By family, twenty-two. There are twenty-two families of things. Here they are. Listen with sharp ears. First there is God.

The ancestors, the serpent Lébé, that’s three, the Binou, speech, the new year at winter solstice, that’s six, reconciliation, springtime, the rainy months, that’s nine, autumn, and the time of the red sun when the earth is parched and cracked.

Hoeing, that’s twelve, the harvest, the smithy, weaving, that’s fifteen, pottery, fire, water, that’s eighteen, air, earth, grass, that’s twenty-one, and the twenty-second is the Nummo, the masters of water with red eyes and no elbows and no knees, like fish.

XIII

Each family has twelve signs, bummo, which we cannot see. They are inside the collarbone, in the crabgrass seed. We can begin to see the signs yala. These are the corners and joints of things, where you can make a point, where lines meet at an angle.

A dot everywhere a dot can be made in the shape of a thing gives us its yala. When you make the yala of a thing it has entered being. Its sign is still in the collarbone but it itself has begun to be here in the world. Four dots can define a field.

The yala are cornerposts, elbows, knees, the point at which a branch grows out from a trunk. Connect the dots of a yala with lines and you have the tonu of a thing. Walls connect cornerposts, shin connects ankle and knee. The tonu are boundaries and structure.

Fill up the yala and tonu with wood, with stone, with flesh, and you have the toy, the thing itself as we know it, as much as Amma means us to know. For Amma a thing is an example of a plan. The bummo is his mind, the toy of that bummo is our world.

As bummo a thing exists as a scratch or wrinkle in the four collarbones rolled into an egg. As yala a thing has come into space. With the tonu it is given its bones and outline. As toy it enters the world, made of Amma’s old squandered God stuff.

What a toy when Amma connects the yala of the stars with tonu! All we can make is what God has thought. Matter is alive, has a soul. In the bummo there already exist the four kikinu, the souls of our bodies, and in them is our life, our nyama.

Nor does the life of things depart, however you change their form. The life of each grain of dust lives on in the mud with which we build a house. The tonu of mud has assumed the toy of house. Still mud, it is also house, bummo, yala, tonu. It is part of God.

For is not a house a still animal, needing a soul? What man touches God has first touched. A man’s seed is yala, the baby in the womb is tonu, the baby is born when it has become toy. So with seed, plant, and fruit. Nit, caterpillar, butterfly.

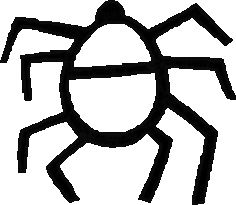

Only Amma sees the bummo in his four collarbones rolled into a ball, though bummo is written in every seed, finer than any eye could ever see. It is written in every crabgrass seed, it is written in the okra, in the spider’s eye, in the stars.

XIV

To get to Fourier’s grave you go along the avenue Rachel to the Caulaincourt viaduct from which steps lead down to the Cimitière Montmartre. Like Père Lachaise this cemetery is a city of the dead, with tombs for houses along streets with names.

Zola lies here, Eugène Cavaignac, Stendhal, Daniel Osiris, Théophile Gautier, Horace Vernet, Berlioz, Dumas fils, and Boum Boum Medrano, of the circus. The leaf-strewn streets are alive with cats who range the tombs and wash their wrists and yawn.

Ask at the lodge and a comfortable registrar in a blue uniform will want to know if you are kin to this Monsieur Fourier. Not by family connection, no. He died when? October 1837. He finds and takes down a ledger from the time of Balzac.

Here we locate the name in menu calligraphy. Someone has written in later sociologue français. His address in this mortuary town is 37 avenue Samson, 23rd Division, second row. Cornices and grilles, soot and leaves, medallions, crosses, angels, flags.

We find the tomb, the geometrical figures, the strange words. La série distribue les harmonies. Les attractions sont proportionelles aux destinées. He died fallen across his bed, as if he’d knelt to say his prayers before sleep, hands clasped together.

His tribe of cats hissed and slunk away when they smelled death around him. At the funeral there were fellow clerks and neighbors, journalists, economists, sallow revolutionaries and disciples. Charles Gide, weeping, laid late roses on the hands.

Hop, thump, and skitter, little Ogo! The armpit drums talk from beyond the brush. Your big ears are up, capacious as ladles, and you stand on your toes. You are too smart to squeak in your kitten’s voice, whistle keen, that is the despair of God.

You imitate the leopard’s cricket chirr at the back of your throat. You hear the drums, the blood drums, and you cock your tail and frisk, grinning sideways with impudent eyes that roll upward and laugh, and let your docked tongue hang out for fun.

You laugh as the acacia laughs in the first rainfall after drought. You dance the dance of the stars when they jiggle in the sky, and toss your stringbean hat for sheer wickedness. We know you are there, Ogo. We know you are laughing at us all.

XV

You kick like a zebra, bounce like a hare. Amma looks at you with distress and you chitter in his face. The lightning walks like silver shears opening and closing across the black clouds, and thunder drowns out the ancestor nummo drums.

The long wind that burns the desert makes your hair stand backward, but what do you care, Ogo fox, when you can peep with your yellow eyes through the okra and laugh? You break the thread in the shuttle, eclipse the moon, muddy the well.

You clabber the milk, mother the beer, wart the hand, trip the runner, burn the roast, lame the goat, blister the heel, pip the hen, crack the cistern, botch the millet, scald the baby, sour the stew, knock stars from the sky, and all for fun, all for fun.

The darkest and utmost wanderer, five billion six hundred million miles from the sun, the planet Fourier is seven hundred times fainter against the absolute black of infinity than yellow Saturn ringed silver by nine titanic moons, unfindable, unseen.

It is now crossing Cassiopeia as it has been since flags floated through the savage smoke at Shiloh and fifty bugles shrill above a roar of drums loosed the red charge at Balaclava, a speck the size of a midge’s eye, a jot of carbon on tar.

It swings so wide afield and so imperially slow that it has been around the sun but four times since Plato was crowned with wild olive at Olympia. It moves backward around the sun, the tenth of the planets and the largest, forever unseeable.

You can see what was most brilliant in the genius of the French at the century’s beginning by considering Jacques Henri Lartigue and Louis Blériot as pure examples of its candor and spontaneity. Lartigue made his first photograph when he was six.

He had an older brother to idolize. His father, a banker who liked automobiles and kites, stereopticons and bicycles, was a splendid father. His mother and grandmother were perfect of their kind. The house swarmed with aunts and uncles and cousins.

There were female cousins who dashed down steps and spilled off their velocipedes, male cousins who jumped fully clothed into the mill race. Papa drove a car like the one drawn by Toulouse-Lautrec, the sort you steer with a stick and start with a crank.

XVI

In goggles and dusters, gauntlets and scarves, they tore over the Seine and Loire, scattering geese, making horses rear. The world children inhabit, floating to the moon in a basket launched from the fig tree, is observation that has become perception.

Little Lartigue so loved places and moments that he began to stare at them, close his eyes, stare again, and keep this up until he had memorized a scene in every detail. Then he had it forever. He could summon it again with perfect clarity.

He knew the fly on the windowpane, the mole on a cousin’s neck, the skiff tethered to a poplar on the canal. His father saw him at this memorizing, asked what he was up to, told him about cameras, and bought him one to externalize and share his vision.

You took a cork out of a hole in the front of the camera to make an exposure. He stood in his father’s joined hands to photograph racing cars zooming by. He followed the racers with a sweep of the camera, getting oval wheels and a forward stretch.

Blériot wept when he saw Wilbur Wright drone up in his Flyer at Le Mans and buzz through figure eights in the blue French summer sky. Blériot’s wasplike Antoinette CV flew like a moth and Wilbur Wright’s mothlike Flyer No. 4 flew like a wasp.

The persistence of the Antoinette would eventually combine with the agility of the Flyer to become the Spad that Captain Lartigue flew over the trenches of the Marne. When Blériot flew across the Channel in 1909, a man walking a dog saw him land.

The man was Henry James. Did he see the Antoinette glide and cough onto English grass and trindle to a halt? He did not bother to say. Birds come before. The soul, if noble, becomes a speckled bird at death, in ancient belief, or dove or raven.

It rides to the world beyond on the withers of an elk. The pace of this progress is solemn, between red larches and past white water, rocks, wolves in naked light, outposts with lamps and turrets, prophets in booths, structures of the utter continuum.

The rattling yaffle of the silver-stockinged rainbird in its scarlet mutch, the owl’s idiot eye, the sparrow’s chat and note, the imperial eagle upon its pole: in the ice-age cave in the Lascaux hills there is a bird on a perch to sign a hunter’s death.

XVII

Amma the Great Collarbone has put his people the Dogon, their altars, granaries, ancestor tortoises, and trees here in this rocky land so hot, so dry. There are no rivers. For nine months of the year no rain falls. The trees are the baobab and tamarind.

The trees are kahya, flame-tree, butternut, sa, jujube, and acacia. At first, from the beginning of time, the Dogon lived in the Mande, before Timbuctoo was there. This homeland was called Dyigou. Then came the men with curved knives, on camels, Islam.

The Dogon brought their altars to Mali. They brought the earth of the first field in baskets and in boats on the Niger. Ogo came with them. That was nine hundred years ago. The earth on which the ark came down they brought to Mali in many baskets.

The forebrain of wasps is built up of a rich tangle of nerve fibers around two quick cups of denser flesh that are like mushrooms of keen mentality and tenacious memory socketed into tissues of casual liveliness and accurate response astride a fat knot.

This central knot seems to be that point around which nature whorls her symmetries. To the right and left of this small brain there stick out like petals the nerves sensitive to light which stream forward and out onto the diamond surfaces of the eyes.

There is yet a third mass of brain that branches down the chest and belly to order the legs, wings, and sting, and to send back the feel of the wind, the wild sweet of coupling, the juicy pull of apple wine, rotten pear mush, the larkspur’s velvet nap.

The keenest nerves cluster in the jaws and stomach. The bigger the mushroom cups in the brain, the smarter the insect, for the spies and gatherers among wasps and bees have the deepest cups in their brains of all the foragers, the sharpest eyes.

They discover all and remember all that’s useful to their lives. Yellow crumbles, soft meal, gum, grains on the grippers, bright. Green is crisp, gives water, ginger mint keen. Yellow is deep, green is long. Green snaps wet, a wax of mealy yellow clings.

Yellow clings and our jaws crunch green. Crunch curls of dry wood. Cling around green, red shine is the line and red shine is wobble the happy and shimmy the sting. Dance the ripen red, hunch the yellow bounce. Red the speckle, green the ground.

XVIII

The red beyond the red is the finest of the dancers and in that tingle shakes a green. Latch green, brush red. She does no spin for she sucks no wine. We dangle when we suck the wine. She is stronger than the brandy. Red then is the green and red the yellow.

The world in his head, Amma began to make the world. The two hundred and sixty-six bummo were written in the collarbone. From himself he took a pinch of filth, spat on it, kneaded it in his fingers, shaping it well, and made the seed of an acacia.

That was the first of all things, an acacia seed. Inside it was the world, all the bummo. The filth that Amma brought up from his throat, that is the earth. His spit, that is our water. He breathed hard as he worked, that is fire. He blew on the seed.

That’s the air. Then he made the acacia tree on which to hang the seed. Amma then took a thorn from the acacia and stood it point up, like the little iron bell called the ganana, the one we ring with a stick, and on this he stuck a lump.

He stuck on it a little dome of acacia wood, so that altogether the two, thorn and dome, looked like a mushroom. Then he stuck another acacia thorn, point down, into the little dome from above. Here he put the two hundred and sixty-six things.

The top thorn he called male, the bottom female. When our children spin their tops they repeat the first dance of the world. How busy is a top, and how still! Amma spun the first world between the thorns, and the seeds of everything were inside.

But — ah! — that little dome, as everybody knows, was Ogo’s paw. This first world failed that Amma made for us. The dome spun but the things inside went wrong. All the water sloshed out. That’s why the acacia tree is both dead and alive, wet and dry.

That is why the acacia is bigger than a bush and smaller than a tree, neither one nor the other, and yet both. It is Amma’s first being. It is therefore a person. And yet obviously a tree. It is both person and tree and neither. It is God’s failure.

Amma saw that he could not make a world out of the acacia and destroyed it, saving the seed, which contains the plan of all things. Amma began a second time to make the world. For the new world he invented people but he decided to keep the acacia too.

XIX

Miss Stein walked home by Les Editions Budé on the corner of the boulevard Raspail and the rue de Fleurus with its yellow Catulles and Tite Lives in the vitrine that made her think of Marie Laurencin and Apollinaire pink and mauve on the Saint Germain.

Rousseau whom Berenson took to be the Barbizon painter and William James the philosopher who wore Circassian dress as by the Pantheon painted their double portrait using a tape measure to get a likeness, poet and muse, Apollinaire who knew so much.

He could see the modern because he loved all that had lasted from before. You see Cézanne by loving Poussin and you see Poussin by loving Pompeii and you see Pompeii by loving Cnossos. What the hell comes before Cnossos if this sentence is to be a long one?

Alice, what comes before Cnossos, what comes before Cnossos, Pussy? The Musée de l’Homme, says Alice, where Pablo says you can’t get your breath, it inspires asthma. On the wall her portrait by Picasso broods and a portrait of Madame Matisse by Matisse.

Madame Matisse in a hat and Madame Cézanne in a conservatory and by Picasso a naked girl holding a basket of roses so glum in her inwardness as to be pouting perhaps for having to pose for Picasso’s eating eyes and her bewildering beauty is in her feet.

The little boy Lartigue was just another French scamp to Wilbur Wright if ever they passed on the Haussmann and Wright was but a lean Anglais to Lartigue. She picked up a notebook and wrote: fact in Cézanne is essence. Sunlight is always correct.

Wilbur Wright was Ohio and Ohio is flat and monotonous, green and quiet. And so was he, a splendidly tedious man. You cannot be a mechanic and not be tedious, nor the first man to fly and not be green as Ohio is green, nor a hero and not be quiet.

After he flew at Le Mans in figure eights Blériot wanted to kiss him on both cheeks in the French way and the aviators wanted to take him on their shoulders to a banquet but he said that he was too busy and had to make adjustments on his machine.

Wasps in an Ohio orchard, fat black bees in an English garden, butterflies at Fiesole. Wasps drunk on nectar grabble into a yellow umble licorice and lavender, bourrée and gigue. Ant tells the poppy when to bloom, and sleeping lions make mimosa spread.

XX

Picasso’s little girl with a basket of roses has a tender button you can believe and has thrummed it with her grubby finger. She has a good French notion of why big girls whisper and why women sigh. She knows perfectly well why little boys are impudent.

Little boys with their silly spouts and bubbles. She knows why roses ripple round like cabbages and why her name is Rose. Her name is Rose. Fat and intelligent, she sat with her notebooks and pictures around her, brooding and writing and seeing.

Alice was mincing a duck. Outside, to the left, was the Raspail, to the right, the Luxembourg where a captain of artillery first noticed the polarization of light, windows reflecting windows reflecting the level late brilliant winter sun.

On the Raspail she had seen Wilbur Wright looking like a U.S. Cavalry Scout as lean as whang leather. In his keen and merry eyes Paris might have been a country fair, a dream, a postcard from an old trunk. People in Paris are all somehow somebody for sure.

People in Pittsburgh on the other hand are always nobody. But the people in Pittsburgh know who’s who. In Paris you don’t ever. Sir Walter Scott on the stairs of a hotel asked James Fenimore Cooper if he knew how to find James Fenimore Cooper.

For years she didn’t see that and didn’t like the painting, it had charm but not the charm of a painting. At Deauville every white and blue building of which is by Boudin you rarely see a barefoot girl except the feet of the Gypsy children naked and brown.

Gypsy children with long innocent brown feet and in the Bois you can see little boys who have terrified their bonnes by shedding their shoes but little boys’ feet are square and with a knarl of ankle and curled toes but Picasso stops at nothing at all.

There are lovely little girls’ feet in Mary Cassatt who came to 27 rue de Fleurus and said I’ve never seen so many ugly people in all my life, or so many ugly pictures, take me home away from all these Jews, and lovely feet in Degas and yes Murillo.

But they, Degas and Cassatt, were inside painters and kept to the pretense like Henry James that art was art and life was life. Picasso sees all and will paint all in time, even the inaccrochable, wait and see, that was next you could be sure.

XXI

Amma began the second world by making the smallest of the grains, the crabgrass seed, in which he put the two hundred and sixty-six things. A yala, the corners and turn of things by dots. They are there, in a spiral. Sixty-six of the yala are the cereals.

The next four are calabash and okra. The next hundred and twenty-eight are The Great Calabash Round. The last sixty-four are the seed itself, the four collarbones rolled into a perfect roundness. The first six yala are male, like the crabgrass.

Three is a male number, penis and testicles. Twin males begin the series. Even Ogo once had a twin. The acacia belongs among the cereals, first of the sixty-six yala. But, having nyama, a human soul, it is also a person. It is Amma’s tree and Ogo’s paw.

Wasps in the Baltic amber of the Eocene ran afoul of that pellucid gum eighty million years ago, grave queens eating all of an autumn day against the winter’s sleep, fatherless males out foraging in the half light of swamps, worker daughters looking to the young.

The structure of their society in the Eocene is unknown. They enter creation with flowers, and their sharp eyes would have seen the five-toed horse, the great lizards, forests of ferns, daylong twilight under constant clouds and eternal thunder.

How they learned to make paper nests, neatly roomed with hexagonal cells, we cannot begin to know, nor how they invented their government of queen and commoners, housekeepers, scouts and foragers, nurses and guards at the door of the hive.

Ogo. The white fox of the brush, Griaule said. He was to have been one of the spirits of time and matter, a nummo like his brothers and sisters. In the collarbone, among the thoughts of Amma, he was greedy. He misbehaved in the crabgrass bummo.

He bit the placenta of all things. He was looking for his twin before Amma was ready to give him his twin. And then, by nobody’s leave, he went on a journey, to see creation. Creation, you understand, was still at this time inside Amma’s collarbones.

Space and time were still the same thing, unsorted. So before God extended time or space from his mind, Ogo began to create the world. His steps became time, his steps measured off space. You can see the road he took in the rainbow. To see creation!

XXII

Amma, Amma! little Ogo squeaked. I have been to see creation! Before I have created sun and shadow, Amma cried in fury and despair. Chaos, chaos. Mischief. Oh, but Ogo also stole the nerves inside the egg of Amma and made himself a hat to wear.

Ogo’s bonnet. They were the nerves with which Amma was planning to make the stringbean. The stringbean is Ogo’s bonnet. Not only that, and worse, but he put the bonnet on backwards, for impudence. For hatefulness. To add fun to his Ogo sass.

Amma cut off part of Ogo’s tongue for that foolishness. That is why Ogo barks hoarse and high. His pranks nevertheless went on full career. He stole part of the world’s placenta, made an ark, and came down to the unfinished world way before he was welcome.

He played God, and havoc. He made things out of the piece of placenta he stole. Look at the plants he made, all in Ogo style: sticktight, mimosa, thorny acacia, dolumgonolo, hyena jujube, Senegal jujube, whitethorn, pogo, redtooth, balakoro, and bombax.

He made crabgrass, indigo, atay, cockleburr, arrowwort, brush okra, broomsedge, tenu, toadstools, gala. And look at them, all, all inedible. He made insects, waterbugs with one side of the placenta, grasshoppers with the other. He made ticks.

He made aphids. He made all these as he was falling through the air, figure eights all the way down. Amma turned the placenta into our earth, and tried to do what he could with the things Ogo created, so that they would fit together somehow, some way.

But the way Ogo made the world was not the way Amma would have made the world. And then there’s Dadayurugugezegezene. Spider. She’s the old bandylegs who tends to Ogo’s spinning, what a pair, and she lives in the branches of the acacia tree.

When Acacia reached the earth in Ogo’s ark, it took root, and ended the disorder of the descent, spiraling like a falling leaf, down the birth of space and time. Amma came behind, putting things in place. Acacia is Ogo’s world. It is his sign.

Its thorns are his claws, its fruit the pads of his little feet. Like Ogo, the acacia is incompletely made. Like him it searches for its twin. It searches in sunlight the completion of its being. It must search forever, never finding, like Ogo.

XXIII

Leaves fell on Fourier’s grave and we thought of the Hordes moving from phalanx to phalanx like fields of tulips. That morning we talked with Fourier’s publisher on the rue Racine. We talked about the attempts to build phalanxes in Europe and America.

We told him how the last phalanx in the United States, outside Red Bank, New Jersey, had recently been bulldozed, a large wooden hexagon of a building beautifully covered with kudzu and still inhabitable. The owner bulldozed it rather than sell it.

He would not sell it when he learned that the damned place had been built by Communists. No grand orgies of attractions by proportion and destiny were ever holden to music in its rooms, no quadrilles danced at noon or at midnight there.

No Hordes of children ever set out on quaggas from its gates. About the time this New Jersey phalanstery was sinking into transcendent boredom, having misfollowed Fourier, not quite believing him, German hunters in Africa shot the last quaggas.

The acacia twists in a spiral as it grows. That is its journey. See how its bark is twisted on the bole. See how the branches spiral up. That is the way it spun as it fell in Ogo’s ark, turning and turning, casting out the seeds of all other things.

Dada the spider was sent by Amma to set Ogo’s chaos in order. Seeing the wild career of Ogo, she decided that he and not Amma would be the landlord of the world. She heard him brag how he had stolen bummo, the plan of all creation from the crabgrass.

What grows, spins. So Dada began a web in the acacia, around and around, digilio bara vani, weaving a cone with its point toward the earth. She spins to the right, the acacia in its growth spins to the left. Amma’s world is a cone turning opposite a cone.

She spins Ogo’s word, which is nothing but the word move. The world is atremble, it vibrates, it shifts from one foot to another, it shakes, it dances its dance. It dances Ogo’s dance. Did I say he wears his stringbean hat backwards for sass?

Ogo talks with his feet, leaving his tracks in the plan of the ark we draw every evening at the edge of the village. The signs he marks with his paws are the signs we must live by that day. For it is Ogo’s gift that he built accident into the world’s structure.

XXIV

Mr. Beckett in the Closerie des Lilas lit an Henri Winterman cigar and sipped his Irish whisky. Joyce, he was saying, had first lived somewhere around Les Invalides when he and Nora first came to Paris. They moved, it seemed, every month thereafter.

This was Nora’s doing. She was trying to find Galway in Paris, I think. A charming smile softened the hawk’s gaze that we knew from photographs. He wore a tweed jacket, old and mended, corduroy trousers, and black turtleneck sweater, and socks.

The socks, we knew, were unusual. His briefcase on the table bore the initials SB above the clasp. Joyce, he said, liked the epigraph from Leopardi on the title page of his Proust because il mondo could be made to sound like the French immonde.

É fango il mondo. The sentiment flowed back and forth from Italian to French, declaring that the world is nasty. We had remarked at Les Invalides that here was the Napoleonic museum in the opening of the Wake and the riverain of Napoleon’s will.

And the concealed Stephen in past Eve and, and he smiled again at God knows what memories of the alert blind face asking the Greek for this and the Gaelic for that, the ringed fingers tip to tip. He’d a letter from Lucia in England that day.

Jarry with his powdered face had sat in this room, sipping Pernod with the dour Gide. Picasso had sat at these tables drawing caricatures of Balzac and Hokusai. Here Ford and Hemingway corrected the palustral proofs of The Making of Americans.

You must understand, Becket said, that Joyce came to see that the fall of a leaf is as grievous as the fall of man. I am blind, Ogotemmêli said, opening a blue paper of tobacco with his delicately long wrinkled fingers, his head aloof and listening.

Tobacco gives good thoughts. We are all blind in relation to Amma. You must go into the caves where the contents of Ogo’s ark are painted in tonu. There are shepherds who will take you. You must see the shepherds when they dance in Ogo’s skirt.

They wear the masks and bloody skirts and make the drums speak. I shall never see them again, except in my mind. The dancers come from afar. They have been away for days. They enter the bounds wearing the masks of creation. They wear the granary and the ark.

XXV

They wear the ark of Ogo and the granary of the world and the skirt of the earth bloody from Ogo’s rape. We fire the Frangi rifles. Our hearts are light, our hearts are gay. It is a funeral and a birth. The eight families of drums begin to beat at dawn.

The Hogon in his iron shoes is with his smiths. The Lébé serpent is to dance for us again. The sun is bright and hot upon the granaries. The altars run with blood. We cry with joy. The calendars are right, the great calendar of the sun, the yazu star.

Venus, said Griaule. And, said Ogotemmêli, the calendar of sigi tolo. Sirius. Once Ogo had hastened creation and wrecked it, the world needed uguru. Another ark had to descend from heaven. All had to be reorganized, redone, reset in their ways, made over.

This was the work of the nummo anagono, the catfish. The nummo were in the placenta that Ogo had not stolen. They were twins. The mud-wiggler catfish, nummo anagono titiyayne, would be the victim, by his own wish, the sacrifice, the redeemer.

He is the beginning of sacrifice. Our altars are in quincunxes because that is the way his teeth fell when he submitted to disintegration. First he was separated from the umbilical cord by which he was attached to Amma in the collarbone.

The cord lay across his penis, which was cut away with the cord. It is now in the sky, the star Sirius, spindle of the world, the pole, the hub. The blood from this severing became the stars. Their spiral is the turning of the world. O greater than acacia!

Greater than Dadayurugugezegezene’s work, greater than Ogo’s work! The sperm spilt from the testicles of the Nummo became the male waters of wells and rivers and springs and the female water of the sea, the great ax of the rain in its season.

The sperm became the dugoy stones which are the twins of the grains, the cowries, and the catfish anagono sala. These six things are in the crabgrass seed. The Nummo, to organize the world half made and crazy, circumcised Ogo and made the sun.

The sun is Ogo’s foreskin. That is his female twin whom he can never approach, for the fire of the sun is intolerable to be near. As the sign on earth of the sun, the lizard nay is Ogo’s foreskin. Foreskins are female. It is chaos we slice away in circumcision.

XXVI

When we circumcise we take the chaotic element from the male, the female part of the male. We are born into Ogo’s world, and our work is the Nummo’s, to organize. We are nummo in the womb, an unborn child is a catfish, anagono, and when we die.

We are born crazy, full of mischief, like Ogo. From the woman we take her clitoris, from the man the foreskin. The sun is woman, the moon man. Sirius is the center of the sky, and around him there circles a star you cannot make out with the eye.

The center of the earth is the crabgrass seed. Balance of quinces, basket of oranges. Alice, tell me, tell me, Alice, how so settled a soul as I can be so giddy about la gloire. About what? says Alice. La gloire. You have it, says Alice, whatever it is.

Wilbur Wright flying around the Statue of Liberty and then up the Hudson over all those warships and dipping down to receive the hoot of the Lusitania’s whistle, c’est la gloire. Nijinsky up there at the top of his leap looking like the young Gorki.

You’ve got flying on the brain, says Alice. Besides, Nijinsky has gone crazy. They say he thinks he’s a horse. There is nothing more worthy of admiration to the philosopher’s eye, Dr. Johnson said, says Gertrude, than the structure of animals.

What a strange thing for Johnson to have said, says Alice. It is of course architecture that is most worthy of admiration and his not saying so is an example of not seeing architecture. People don’t, people who walk take architecture for granted.

They take it for granted because it is good. When everybody has an automobile as in the United States architecture will go all to hell. Architecture is for people on foot. The Chinese had no architecture, nor the Magyars, until they got down off their horses.

There is no architecture in America, never will be. A skyscraper is a city street turned on end. But, says Alice, we drove our Ford through the War. We have seen the trenches of the Ardennes. You have lectured at Oxford and you have lectured at Cambridge.

And at the Wednesday Club in St. Louis. We own Picassos and Cézannes. We have stayed with the Alfred North Whiteheads. Cocteau says he is influenced by you. It is not enough. We have passed Joyce and that Frenchman Fargue on the Victor Hugo.

XXVII

The Frenchman raised his hat to us, Joyce did not. He didn’t see us. L’aveugle et le paralytique, the concierges call those two. It is not enough. We saw the victory parade through the Arc, down the Elysées, O grandest of days, except one other.

When the nummo circumcised Ogo, Amma said: You should have waited. I could have destroyed him utterly. Now you have mixed his blood with all of creation. So Amma reversed the spiral of the nummo, took the sacrifice, and drenched the world with blood.

Stars began to turn, grain came up, rain fell, wind blew. The fellow traveler of Sirius is the crabgrass seed above, female twin to the crabgrass seed down here. That little star, which many cannot see, unsuspected by some, we know to be the world’s granary.

The day after his sacrifice there sprang from the Nummo’s blood the donu, whose blue wings flash on the Niger in the season of the rains. And the antelope. The Nummo danced as a serpent under our fields. His eyes are red like the first light of the sun.

His skin is green. For legs he has snakes, and his arms are without elbows or wrists. He eats light, and his droppings are copper. But we do not see the Nummo as he is, only his presence in catfish, rain, trees. The Nummo is in the shine of things.

The crabgrass is the granary, the basket the ancestors brought from heaven, the ark of the two hundred and sixty-six things. It is the menstrual blood. You have seen wild rams on the rocks near the village at dusk? You have seen a little of the Nummo.

The light in the fleeces of the wild rams is wonderful. You see the Nummo when rain walks in its season from the east, smelling of the river, of green leaves. You see the white of it under the clouds before the first fat drops fall on our red dust.

That is the Nummo. The rain ram. Split a green stick halfway down. Run your knifeblade up each tine so that it curls. That is his sign. You have seen it above the smith’s door. Even the French must have seen him in the yala of the stars, the Ram.

Between his horns is the sun, the Great Calabash, which is female, the seed basket, the granary, the crabgrass. His horns are testicles, his forehead the moon, his eyes stars, his mouth and his bleat are the wind. His fleece is the earth, the very world.

XXVIII

His fleece is of course copper, which is to say, of water, which is to say, of leaves. When the wind speaks in the leaves and a light like burnished copper dances in the green, and rain falls, that is the presence of the Nummo. His tail is the serpent Lébé.

Lébé danced under our fields when he swallowed his brother ancestor and spat out the dugoy stones, the points and junctures of the world. His front feet are the small animals, his hind feet are the big animals, and his mentula is the rain.

The granary. It turns in the middle of the air. At the zero point of time its four sides faced the Fish of the Twin Nummo, the Nummo, the Woman with the Grains, and the Nummo with the Bow. Now time is out of kilter, askew, but turning again to zero.

The floor of the granary is round, the roof square, so that the walls rise from their foundation as a cone and find in tapering upward the four creases of the roof’s corners. Up each side, in all four directions, there is a long stairway.

The stairway is of ten steps, female on the tread, male on the rise. On the western stairs are the untamed animals, antelopes at the top, and then downward are hyenas, cats, snakes, lizards, apes, gazelles, marmots, lions, and the elephants.

Beside the animals on their steps are the trees in order, from baobab to mimosa, together with all the insects. The tame animals stand on the south steps, chicken, sheep, goats, cattle, horses, dogs, house cats, ancestor tortoise who lives in the yard, mice.

House mice and field mice. On the eastern steps are the birds, hawks, eagles, ospreys and hornbills majestic at the top. Then ostriches and storks. Buzzards and lapwings. Then vultures, chicken hawks, herons, pigeons, doves, ducks, and bustards.

On the northern steps are fish and men. The fish are joined at their navels, like the two fish in the stars. There are four kinds of women, pobu, whose wombs are shaped like beans and who have malformed children unfortunate to behold, a grief.

There are women with a vulva like an antelope’s foot who bear twin boys, women with a double womb who have twins of different sexes, women with wombs like the crabgrass spiral inside its seed who have twin girls. These are all the kinds of women.

XXIX

There are three kinds of men, men with a short thick mentula, men with a mentula like a lizard’s head, and men with a fine long mentula. Our fields are our shrouds. We will be catfish when we die and return to Amma. We are silent at night, lest we stink.

In sixty of Ogo’s burrows are hidden the sixty ways of being. We know twenty-two of these: the world, villages, the house for women during their periods, the house of the Hogon, the granary, sky, earth, wind, and animals who have four feet.

Birds, trees, people, dancing, funerals, fire, speech, farming, hard work, cowrie shells, journeys, death and peace. The Nummo’s face is leaves and flame. The other thirty-eight ways of being are all that stand between us and Ogo.

They shall be known in time. They are like the young shepherds who have not been seen for weeks in the village, who have gone away in discipline, and who come all unexpected to dance Ogo’s dance. Long before they come we hear their drums from afar.

We hear the smith’s drum and the armpit drum. The drums speak to the Nummo, for the Nummo. We will have been hearing the drums a long while before we see the young men in their bloody skirts leaping in the first light, wearing Ogo’s bonnet.

They wear Ogo’s bonnet and pipe in his thin voice. The unshown things will be revealed to us slowly at first, and dimly, as in a mist at dawn, an awakening and a coming, but suddenly and swiftly at the last, like a loud stormwind and rain.

Everybody was on the streets, men, women, children, soldiers, priests, nuns, we saw two nuns being helped into a tree from which they would be able to see. And we ourselves were admirably placed and we saw perfectly. We saw it all.

We saw first the few wounded from the Invalides in their wheeling chairs wheeling themselves. It is an old french custom that a military procession should always be preceded by veterans from the Invalides. They all marched past through the Arc.

They all marched past through the Arc de Triomphe. Gertrude Stein remembered that when as a child she used to swing on the chains that were around the Arc de Triomphe her governess had told her that no one must walk underneath.

XXX

Her governess had told her that no one must walk underneath since the german armies had marched under it after 1870. And now everyone except the germans were passing through. All the nations marched differently, some slowly, some quickly.

The french carry their flag best of all, Pershing and his officer carrying the flag behind him were perhaps the most perfectly spaced.