Decoding jazz standards.

This chapter can be read in conjunction with video lessons 18 and 19.

Click here to purchase lesson18.

Click here to purchase lesson 19.

Towards the end of chapter 2, I referred to Jerome Kern’s All The Things You Are. Although I would hesitate to describe Kern as a better songwriter than Irving Berlin, he certainly had a more sophisticated knowledge of harmony, and this fact alone has much appeal to the jazz improviser. As we will later discover, this beautiful tune journeys through no less than five keys in the space of 36 bars.

In any well-written song, both melodic and rhythmic repetition feature strongly. The repetition and variation of melodic phrases makes the song easier to digest. It also provides the singer or instrumentalist with breathing spaces between these phrases.

Composers and lyricists are constantly asked the same question about songwriting: which comes first – the melody or the lyrics? Later in his career, when the lyricist Oscar Hammerstein was working with Richard Rogers, Hammerstein chose to write the lyric before handing it over to Rodgers, the composer. Hammerstein took great care with breathing places and choice of vowel sounds that the singer requires to sustain a note. Both these considerations are even more critical in a ballad (a slow, lyrical song) such as All The Things You Are. However, back in the late 30’s Hammerstein didn’t have this luxury, as Kern insisted on writing his tune first. Here is the melody and lyrics of the first eight bars.

Although some singers need to take a breath after the word ‘are,’ the natural end of the first phrase is ‘springtime.’ We therefore have two phrases:

1. You are the promised kiss of Springtime

2. That makes the lonely winter seem long.

The next 8 bars follow the same pattern, but in a new key.

1. You are the breathless hush of evening

2. That trembles on the brink of a lovely song.

At bar 16, there’s a pick-up of three quarter notes that leads into the 8-bar B section (also known as the bridg or middle eight. Once again, the second phrase echoes the first, but in a new key.

Although a singer may need to breathe after ‘glow,’ the natural end to phrase 1 is ‘star.’ Similarly, a breath may be required after ‘know,’ but phrase 2 should drive on until ‘are.’

1. You are the angel glow that lights a star.

2. The dearest things I know are what you are.

The final ‘C’ section contains just three phrases; phrase 1 echoing the very first phrase of the song.

1. Some day my happy arms will hold you.

2. And some day I’ll know that moment divine

3. When all the things you are, are mine.

Although the words are not exactly Wordsworth, (I’ve yet to meet anyone with happy arms), I would recommend that you acquaint yourself with the lyrics of a song. It not only brings the tune to life; the song structure also becomes more apparent. And it’s not only singers and brass players that take a breath between phrases. I’ve recently noticed doing this myself when soloing on piano!

There are countless excellent recordings of this song, but my personal favorite is by the pianist Hampton Hawes. The solo introduction is a little flowery, but once the trio kicks in, Hawes creates one glorious idea after another. See chapter 10 for details of this recording.

The song structure is usually described as ABC: 16 + 8 + 12 = 36 bars.

• A1 states the melody.

• A2 repeats it in a new key.

• B, the bridge, introduces a new 4-bar phrase and then transposes it down a minor 3rd.

• C returns to the original melody, but remains in the same key, taking four extra bars to conclude.

The form could also be described as AABA: 8 + 8 + 8 + 12 = 36 bars.

A good songwriter takes great care when placing the targeted or emphasized melody note over its harmony. A strong, grounded melody note might be 1 or 5, but a more lyrical note is 3. This is Kern’s choice for most of his tune.

A song can be in any key that the singer or bandleader chooses. However, tunes played as jazz instrumentals often have default keys. All The Things You Are is usually written in Ab major, so I’ll stick with that.

Here are the first 16 bars.

I’ve boxed all the 3s. Notice how every 3, with two exceptions, falls on beat 1 of the bar.

The two exceptions, in bars 4 and 12, occur on beat 2, as this is where the melodic accent falls.

====================

Root movement

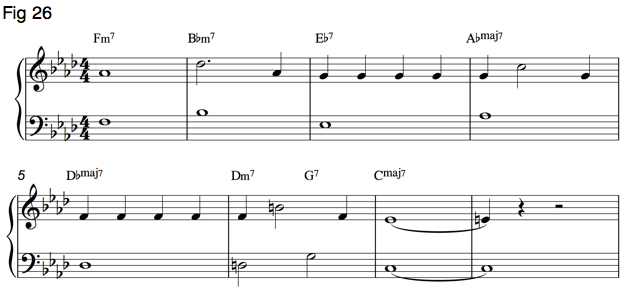

One way to learn a song’s chord sequence is to follow its harmonic journey through the root movement. Play the melody, together with just the root of each chord, as in fig 26, below.

Here are bars 1 – 8.

From bars 1 – 5, the root moves through the circle of 5ths.

• Remember that moving down a perfect 5th reaches the same note as moving up a perfect 4th. This is why the circle of 5ths is sometimes called the circle of 4ths.

Fig 27 illustrates this movement. I’ve transposed it to the treble clef.

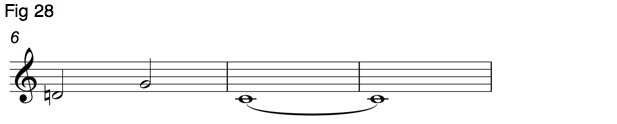

Then, at bar 6, after shifting up a half step, the root moves through another circle of 5ths.

Here are the first 8 bars of All The Things You Are, just showing the root movement in the bass clef, plus the target notes in the treble clef. The interval between left and right-hand notes is a tenth (octave + major 3rd).

====================

Mapping the harmony

We’ll now analyze the harmony of these first 8 bars. Whenever you first encounter a song, follow this simple procedure:

1. Identify the key signature.

2. Locate every dominant 7 chord. Does this chord resolve to its tonic? Does it follow on from its minor 2 chord?

Here’s the chord sequence for bars 1 – 8. I’ve boxed the dominant 7s.

• The key signature of four flats indicates either Ab major or F minor.

• There are two dominant 7s.

• In both cases, the chord that follows has moved up a perfect 4th to its tonic.

We have therefore established two V – I pairs:

Eb7 – Abmaj7

G7 – Cmaj7

Eb7 – Abmaj7 suggests that we are in the key of Ab major rather than F minor.

G7 – Cmaj7 indicates a transposition to the key of C major.

Now examine each chord that precedes these two dominant 7s.

• Bbmin7 leads to Eb7

• Dmin7 leads to G7.

Again, the interval between these two chords is a perfect 4th.

TIP: When a minor 7 chord is followed by a dominant 7 a perfect 4th up, the resulting sequence is II – V.

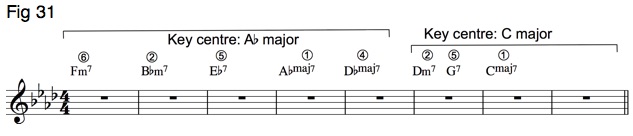

We can now identify two sets of II – V – I sequences in these 8 bars.

• Bbmin7 – Eb7 – Abmaj7

• Dmin7 – G7 – Cmaj7

The first 5 chords are all a part of the same family within the key of Ab major.

The 3 chords in bars 3, 4 and 5 are numbered as follows:

Bbmin7 = II

Eb7 = 5

Abmaj7 = I

We can now number the remaining two chords in this key centre:

• Fm7 is at bar 1 and Dbmaj7 is at bar 5.

• Fm7 is on pitch 6 of the Ab major scale and Dbmaj7 is on pitch 4.

So here’s how bars 1 - 5 number up.

Bar 1: Fmin7 = VI

Bar 2: Bbmin7 = II

Bar 3: Eb7 = V

Bar 4: D bmaj7 = IV

The second key centre, from bars 6 to 8, is C major.

Bar 5: Dmin7 = II

Bar 6: G7 = V

Bars 7 and 8: Cmaj7 = I

Here’s the complete picture from bars 1 – 8.

These first 8 bars can be referred

to as A1.

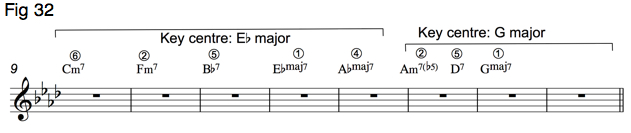

The following 8 bars, A2, follow exactly the same pattern, but transposed up a minor 3rd.

(At bar 14, Amin7 contains flat 5. This is to accommodate the melody, which, at this point, hits the note Eb.)

We can now summarize the key centres of the 16-bar A section.

• Bars 1 – 5: Ab major

• Bars 6 – 8: C major

• Bars 9 – 13: Eb major

• Bars 14 – 16: G major

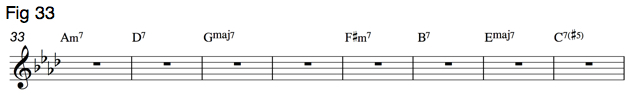

Can you now identify the key centres in the 8-bar bridge?

This B section remains in the key of G major,

commencing with another

II – V – I.

This is followed by a second II – V – I, but now in E major.

The final chord, at bar 40, is a dominant 7 that points back towards the original key of Ab major. The sharp 5 supports the melody note of G#.

Therefore, the key centres of the bridge are as follows:

• Bars 33 – 36: G major

• Bars 37 – 39: E major

• Bar 40: a single, linking dominant 7 that will lead us back to the original key of Ab major at section C.

Traditionally, it is the composer’s job to devise a route back to the original key and then remain there till the end of the song. The final 12 bars (section C) therefore remain in the key of Ab major.

You will recognize the chord sequence from bars 25 – 29. This is because it replicates bars 1 – 5, found at the start of the song: VI – II – V – I – IV in the key of Ab major.

However, in that first section, A1, Kern veered off into the key of C major. In this final section, in order to remain in Ab major, he follows the IV chord (bar 29) with a minor IV (bar 30), and concludes with VI – II – V – I to take us home.

Note that the III chord at bar 31, Cmin7, has a strong relationship with the tonic (I) chord, in that both these chords share three notes.

III: Cmin7 = C, Eb, G, Bb.

I: Abmaj7 = Ab, C, Eb, G.

Also note the VI chord, F7, at bar 32. This is far stronger, harmonically, than minor 7 for the following reasons.

1. It creates a secondary dominant with the chord that follows:

F7 – Bbmin7 = V – I.

2. It creates a II – V with the chord that precedes it:

Cmin7 – F7

This works well with the melody.

====================