Approaches to improvisation.

Throughout these books I’ve provided you with a range of tools with which to improvise. We’ve studied key centres and the scales that bind them. We’ve looked at extensions, alterations and the scales that work over dominant 7s. We can now talk jazz. But can we play it?

In my introduction to book 1, I suggested that for most of us, instinct alone does not suffice. The majority of artists choose to study technique and theory before these aids merge into the subconscious. For most of us, the magic doesn’t just happen.

In book 2, I said this about instinct:

“Believe me, I'm not belittling instinct. Indeed, the only time I feel I'm playing a decent solo is when I'm not thinking. The last thing I want to be doing is consciously going for a diminished scale or sharp 9. In the same way, when speaking, I'm not thinking about letters of the alphabet; I've done that work.”

So how do we get beyond the theory, and access the magic?

===============

Exploration

When an animal explores, it rarely rushes, but takes its time, checking and rechecking an area before moving on. An inexperienced improviser will do the opposite, and is more likely to make a noisy entrance with all guns blazing.

This is understandable if you have just one chorus to express yourself, but there is normally no need to throw everything in at once. A headlong approach makes it harder on you as well as the listener.

Oscar Peterson and Count Basie recorded and performed together. It was never a competition; this was evident by how comfortable they both looked. Although, had it been a competition for the most notes played, Peterson would have won hands down. Both pianists were masters; however one played lots of notes and the other played few, but making each note count. You can watch some of these performances on YouTube, but I’d particularly recommend Blues in G.

===============

The journey

If you have two or more choruses stretched out before you, begin as though you were setting off on a journey.

Don’t rush in with a flurry or notes. It’s an exploration, not a race. There’s nothing to prove. Take your time.

Even though it’s your solo, your ears should still be open to the drummer and bass player. The more interaction between musicians, the richer your solo will be. Soloing doesn’t mean ‘now it’s my turn.’ It shouldn’t feel that that the spotlight is now on only you, as the others fade into the background. Listen to the Keith Jarrett trio. They are always playing as a unit, whoever happens to be soloing.

===============

Developing each idea

Inexperienced improvisers have a tendency to throw too many ideas into one solo. All these ideas, as creative as they might be, are often far less effective than taking just one phrase and developing it.

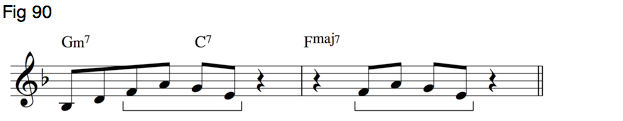

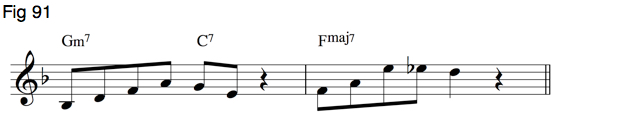

Begin with a clear statement. This can be anything from two notes, to a phrase stretching over a group of chords.

This initial phrase can then be developed in a number of ways. Here are some examples.

1. Reshape the phrase to fit over the upcoming chords.

2. Shift the phrase, so that it begins at a different point in the bar.

3. Develop a fragment of the initial phrase.

4. Respond in a way that answers or echoes the initial phrase.

===============

Developing the melody

If the composer has written a beautiful tune, it seems sacrilegious to immediately disregard it at the moment your solo starts. Players such as Thelonious Monk, Ben Webster and Keith Jarrett seem to delight in the melodies and pay them respect during their solos.

Listen to Monk's April In Paris, Webster’s My Funny Valentine and Jarrett’s Someone To Watch Over Me.

Fig 92, below, is the opening melody of There Is No Greater Love.

And here’s an improvised phrase that reflects this melody.

===============

Creating space

Piano players are guiltier than most musicians of filling every space with notes. Perhaps it’s because we have all those keys laid out in front of us. Or we may feel some irrational responsibility to hold the rest of the band together.

Halfway through a rhythm section workshop, my old piano tutor turned to us student pianists and dropped this bombshell:

“You guys seem to be putting in a lot of work, but perhaps you should reconsider your role as a member of a trio. In one sense, you are redundant. The drummer is providing the rhythm; the bass player is providing the harmony. So, in a way, you have nothing left to do. Instead of playing all those chords and notes, how about just adding to what’s already there?”

He was, of course, exaggerating to get his point across. But his comment has stayed with me. It was, perhaps, the first Bill Evans trio that worked as equal partners. By playing rootless chords and leaving space, Evans allowed Scott LaFaro, the bass player, a much freer rein to weave his own creative lines rather than merely support.

The message can be stated simply: play when you have something to say. Do you know anyone that won’t stop talking? The crude phrase for this affliction is ‘vocal diarrhea’ and many musicians have the musical equivalent. Fortunately, we have an obvious musical guideline for when to play: over the dominant 7.

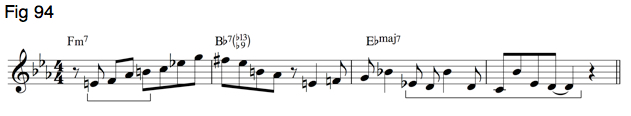

Compare figs 94 and 95.

Although there’s nothing wrong with fig 94, the notes tends to ramble on in areas where there’s little to say.

Fig 95 shaves away redundant material from the start and end of fig 94. What remains is just one concentrated statement that focuses on the tension within the dominant 7. The idea then concludes as it crosses the finishing line of the tonic chord. This approach also opens up space for the bass player and drummer.

===============

Playing over the bar

In fig 96 and 97, I’m using a simple, ascending 4-note phrase: three short notes, then one long note. In both examples, notes are adjusted to fit the

I – VI – II – V sequence.

This is rather dull and predictable, as the phrase and accompanying chord always fall on beat 1.

Compare this with fig 97, below.

Although I’m using the same ascending pattern, the result is far more satisfying, as each new phrase begins on a different beat. The effect is heightened by an accompanying chord played and accented at the top of each phrase, rather than at the start of every bar.

In most situations, the drummer and bass player are already marking beats 1 and 3. Continually placing your chords on these beats may be helping you to keep your place, but it will not benefit the music. Similarly, avoid starting too many phrases on these strong beats.

If the rhythm section is solid, the soloist is free to glide over bar lines. Try comping behind Cannonball Adderley’s solo on Autumn Leaves. (You’ll find this track on the album Somethin’ Else. See chapter 11 for details.) Because the pulse is ever-present, Adderley can express himself without needing to refer to the downbeats.

===============

Two-handed solos

Many learning jazz pianists compartmentalize the function of each hand, using the right for soloing and the left for chords. Keith Jarrett claims not to focus on the chords but rather on creating a polyphonic line with the bass player. In others words, two lines are moving horizontally and the chords naturally occur as the lines interweave.

Try using both hands to create your solo.

• One hand might cross over the other, or you could create rhythms with both hands working together.

• How about trying to play a solo with your left hand only? The result will surprise you. This is because you are no longer able to play the licks and clichés locked into the muscle memory of your right hand.

Brad Mehldau has a strong left hand; Monk explores with both. Watch any video featuring Stan Tracey: a wonderful pianist from the UK.

==================

Eyes and ears

You don’t need your eyes to make music. I’ll go further: the more you look, the less room there’ll be for creativity. While you’re staring at the sheet music, the keyboard or your fingers, valuable ‘magical space’ will be replaced with non-musical clutter. Sheet music is not actually the music; it’s just information. When I’m playing in a band, I only need my eyes to communicate with other musicians for cues etc.

When playing, although I’m not visually focusing on anything, I prefer not to close my eyes. In Zen meditation it is vital to ‘stay in the room’ rather than to float off. One needs to be totally aware and in the present moment. Any top sportsman is doing exactly this. Our own heightened awareness as musicians is in the aural realm. We become one big ear that acts like an antenna, in constant readiness to transmit and receive ordered sound. While we are in this heightened state of listening and responding, how can there be room for looking at sheet music or deciding which scale or lick to play?

There’s nothing special or spiritual about this state of awareness; it’s just human. We have all experienced this state: you might be swimming, eating or involved in a conversation. It is neither excited nor particularly relaxed but calm, aware and totally awake.

You’ve put in the work; now create the music.

====================