Lacan’s Theory on the Four Discourses.

During the late sixties and the early seventies, the intellectual talk of the town was about structuralism and the structuralists, with Foucault, Lacan and Barthes being the most prominent figures. The fact that each of these three denied being a structuralist was considered irrelevant, and added a bit of Parisian spice and frivolity to the discussion.

As far as Lacan is concerned, I find it rather difficult to answer the question of whether he was a structuralist or not. In such a discussion, everything depends on the definition one adheres to. Nevertheless, one thing is very clear to me: Freud was not a structuralist and, if Lacan is the only postfreudian who lifted psychoanalytic theory to another and higher level, then this Aufhebung, elevation in Hegel’s sense, has everything to do with Lacanian structuralism and formalism. The rest of the postfreudians stayed behind Freud, even returning very often to the level of the prefreudians.

It is obvious that Freud was fundamentally innovative. He operated on his own a shift towards a new paradigm in the study of mankind. He was so fundamentally innovative that it would seem almost impossible to go any further. So, if we state that Lacan operates an Aufhebung, we have to explain what we mean by that. What is there to gain with Lacanian theory?

In order to appreciate the gain, we have to return to the fundamental difficulty in every psychological study. Within a classical scientific approach one has to start with observation and description in order to take the step towards categorisation and generalisation. This is the approach of prefreudian and postfreudian psychology and psychiatry, and it is an approach which is doomed to fail. The step from the observation of an individual to a generalised category proves to be a very frustrating business. Everyone who has been trained in psychodiagnostics, being the first step in this kind of scientific approach, knows exactly what I mean. By means of observation and interview with an individual patient, you sample a number of characteristics, which have to match the characteristics dictated by a psychiatric handbook. They have to match, but, of course, they never do. Still within the classical approach, the solution is always a variant on the same theme: one differentiates between primary and secondary characteristics; in that respect, you have for example the primary and the secondary characteristics of schizophrenia. The modern solution to the same problem is illustrated with the DSM, in which there remains an element of choice: a patient is called borderline if he shows at least five symptoms out of a list of eight, etc. There are multiple examples, but these are so boring that I won’t go any further into them.

The more interesting part of it is the ever-returning field of tension between clinical reality on the one hand and conceptualisation on the other. Lacan has summarised this tension in one of his paradoxical statements: “Psychanalyse, c’est la science du particulier”, that is: psychoanalysis is the science of the particular. One of the reasons why Freud was so innovative lies in his solution to this problem. Instead of making his own categorical system in which every patient had to find his proper place and trying to convince the world that his system, and his alone, was the only useful one, he chose a completely different line of approach. Every patient is listened to, and every case study results in a category into which one and only one patient fits. Already in his Studies on Hysteria he remarks that hysteria does not exist as a separate category, that in clinical reality we always find mixtures of different kinds of neuroses, whose pure form is only a matter of ‘textbook-psychology’. The paradoxical result of this Freudian approach, focusing on the individual, even on the individual symptoms of one individual patient, is that Freud is the only one who succeeded in making a general theory on the human psyche. His method is not a secret one, on the contrary. In order to take the step from individual clinical reality to a general conceptualisation, Freud makes use of a ready-made theory, or at least almost ready-made. Indeed, the core of Freudian theory is based on classical myths and stories, with the Oedipus tragedy and the story of Narcissus being the most famous examples. In the last volume of the Standard Edition, we find ten pages filled with references to works of art and literature. Freud goes even further with his solution: where he did not find a suitable myth, he invented one himself, and that is of course the story of Totem und Tabu, the myth of the primal father.

This Freudian approach resulted in a major breakthrough, a new paradigm. Nevertheless, there are a couple of serious disadvantages to it. This method is useful only as long as one keeps the story sufficiently vague. From the moment one studies any individual myth in its own particularity, it becomes part of that science of the particular. Even Oedipus himself had his own version of the Oedipus complex. Within the realm of cultural anthropology, Lévi-Strauss had the same problem, and that is why he considered each myth as a local variant of a hidden matrix. A second and even more important disadvantage has to do with the content of myths and the possibility that this content gets psychologized, which means that it becomes a substantial reality. That is what happened with Jungian and post-jungian theory. We won’t go any further into that, one Lacanian quotation suffices to announce the danger of such an approach. Abbreviated, it runs as follows: “Thus to authenticate everything of the order of the imaginary in the subject is properly speaking to make analysis the anteroom of madness, (…)”.1

In this light, we have to consider Lacanian theory as a major breakthrough. Whereas Freud made the step from the individual patient to the underlying myths, Lacan makes the step from these myths to the formal structures, which govern those myths. The most important Lacanian structure in this respect is, of course, the theory on the four discourses.

The advantages of these formal structures are obvious. First of all, there is an enormous gain in level of abstraction. Just as in algebra, you can represent anything with those “petites lettres”, the small letters, the a and the S and the A, and the relationships between them. It is precisely this level of abstraction which enables us to fit every particular subject into the main frame. Secondly, these formal structures are so stripped of flesh and bones that they diminish the possibility of psychologizing. For example, if one compares the Freudian primal father with the Lacanian master-signifier S1, the difference is very clear: with the first one, everybody sees an elderly greybeard before his or her eyes, roving between his females, etc. It is very difficult to imagine this greybeard using the S1 … which precisely opens up the possibility of other interpretations of this very important function. This brings us to the third advantage: these structures permit us to steer the clinical practice in a very efficient way. It makes a great deal of difference, for example, whether one uses a master discourse or a hysterical discourse in a given situation; the respective formulae allow you to predict what the effect of your choice will be.

There is of course one disadvantage to this system. Compared to the Freudian solution, with the myths and the age-old stories, the Lacanian algebraic structures are boring, tedious even. Indeed, there is no flesh to them, since they are concerned only with the bare bones and, therefore, they completely lack the ever-present attraction of the imaginary order that is pre-eminent in those stories. That is the price one has to pay.

The theory of the four discourses is without any doubt the most important part of the Lacanian formalisation. The discourses are the summary and — as far as I am concerned — the summit of Lacan’s theory.2 This implies that they are very dense and quite difficult. At the same time, they are also very easy to understand and to handle, once one has grasped their inner logic. The ever-lurking danger is that one reduces each discourse to one concrete implementation, resulting in a return to the captivating imaginary scene. In the long run, the only answer to this captivation of the imaginary lies in one’s own analysis.

The idea of communication has been the focus of attention in many different fields for the last twenty-five years, starting with ‘human relations’ and on to electronics and to genetics. There is one unifying aim which characterises those different aspects of so-called communication theories: they want to bring communication up to a perfect standard by eliminating any kind of “noise” so that the message can flow freely between sender and receiver. The basic myth governing those theories concerns the existence of the perfect communication, without any failure whatsoever.

Those theories are very different form the original concept of discourse, as it was coined by Michel Foucault in December 1970 during his inaugural speech at the Collège de France. For him, there is a very special relationship between power and discourse. The impact of a given discourse makes itself clear by imposing its signifiers on another discourse. For example, when, during the Gulf war, bombing was described as “surgical measures” carried out with “surgical precision”, these metaphors express the power of the medical discourse, because they are used outside the proper field of their application. In this respect, the analysis of discourse is a very useful instrument within the framework of historical research on the evolution of power, which is precisely what Foucault wanted to do.

And now for something completely different. The Lacanian theory has nothing to do with either of those two. His theory is even in radical opposition to communication theory as such. Indeed, he starts from the assumption that communication is always a failure; moreover, that it has to be a failure, and that is the reason why we keep on talking. If we understood each other, we would all remain silent. Luckily enough, we don’t, so we have to speak to one another. The discourses stretch a number of lines along which this impossibility of communication can take place. This brings us to the difference from Foucault’s theory. In his discourse theory, Foucault works with the concrete material of the signifier, which puts the accent on the content of a discourse. Lacan, on the contrary, works beyond the content and places the accent on the formal relationships that each discourse draws through the act of speaking. This implies that the Lacanian discourse theory has to be understood primarily as a formal system, i.e. independent of any spoken word as such. A discourse exists before any concretely spoken word; even more: a discourse determines the concrete speech act. This effect of determination is the reflection of the Lacanian basic assumption, namely that each discourse delineates fundamental relationships, resulting in a particular social bond. As there are four discourses, there are four different social bonds.

Before we go into that, I want to emphasize again the a priori emptiness of each discourse. They are nothing but empty bags with a particular form, which determines the content that one puts into them. The important thing to understand is that they can contain almost anything. The moment one reduces a given discourse to one interpretation, the whole theory implodes and one returns to the science of the particular.

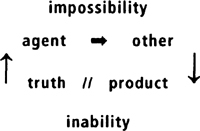

What does the discourse bag look like? Each bag has four different compartments into which one can put things. The compartments are called positions, the things are the terms. There are four positions, standing in a fixed relationship to each other. The first position is very logical: each discourse starts with somebody talking, called by Lacan the agent. If one talks, one is talking to somebody, and that is the second position, called the other. Those two positions are nothing else but the conscious expression of each speech act, and in that sense we can find them in every communication theory:

Within this minimal relationship between speaker and receiver, between agent and other, one aims at a certain effect, that is, there is a purpose to it. The result of the discourse can be made visible in this effect, and that brings us to the next position, called the product.

An example is when you tell your son to work hard at school and, as a result, he produces one failure after another. Up to this point, we are still within classical communication theory. It is only the fourth position that introduces the psychoanalytic perspective. As a matter of fact, it is not the fourth, but the first position, namely the position of the truth. Indeed, Freud showed us that, while speaking, we are driven by a truth unknown to ourselves. It is this position of the truth which functions as motor and as starting-point of each discourse.

The position of the truth is the Aristotelian Prime Mover, affecting the whole structure of the discourse. Its first consequence is that the agent is only apparently the agent. The ego does not speak, it is spoken. Of course you can come to this conclusion by looking at the process of free association, but even normal speaking yields the same result. Indeed, when I speak, I do not know what I am going to say, unless I have learned it by heart or am reading my speech from a paper. In all other cases, I do not speak but I am spoken, and this speech is driven by a desire, with or without my conscious agreement. This is a matter of simple observation, but it is fundamentally wounding to man’s narcissism; that is why Freud called it the third great narcissistic humiliation of mankind.3 He coined it in a very clear statement: “dass das Ich kein Herr sei in seinem eigenen Haus” (The I is not master in its own house). The Lacanian equivalent of this Freudian formula runs as follows: “Le signifiant, c’est ce qui représente le sujet pour un autre signifiant” (the signifier is what represents the subject for another signifier). In this readjustment of the scales it is not the subject who stands to the fore in the definition; rather, all importance goes to the signifier. Lacan defines the subject as a passive effect of the signifying chain, certainly not the master of it. So, the agent of the discourse is only a fake agent, “un semblant”, a phoney. The real driving force lies underneath, at the position of the truth.

The second consequence of the introduction of this driving force is that the communicative sequence of the discourse is disrupted. One would expect an almost logical line according to which the agent translates the truth into a message directed to the other and resulting in a product which, in a feedback movement, returns to the sender. This is not the case. In Lacanian theory, there is no such thing as a truth, which can be completely put into words; on the contrary, the exact nature of the truth is such that one can hardly put words to it. Lacan calls this characteristic “le mi-dire de la vérité”, the half-speaking of the truth. This is essentially a Freudian idea: the complete verbalisation of the truth is impossible, because primary repression keeps the original object definitively outside the realm of language, which means at the same time Beyond the Pleasure Principle, with as a consequence the endless compulsion to repeat, as a never-ending attempt to verbalise the non-verbal. The consequence is the endless insistence of this “mi-dire de la vérité”, which was beautifully expressed by Kierkegaard in his book on repetition: “Repetition is a beloved wife, which one never gets tired of.” As a consequence, every discourse is an open-ended structure, in which the open-endedness functions as causal factor. Because of the structural lack, the discourses keep on turning. Already in 1964, at the time of seminar XI, Lacan had described the unconscious as a process of “béance causale”, a gap with a causal function, in a typical movement of opening and closing. It is this idea that he retakes in the discourse theory.

Besides these four positions, the formal structure of a discourse consists of two disjunctions, expressing the disruption of the communicative line. These disjunctions are the most important and the most difficult part of the whole theory. On the upper level of the discourse, we have the disjunction of impossibility; on the lower level, we are confronted with the disjunction of inability. The two are interrelated.

On the upper level, there is the disjunction of impossibility: the agent, who is only a make-believe agent, is driven by a desire which constitutes his truth. This truth cannot be completely verbalised, with the result that the agent cannot transmit his desire to the other; hence a perfect communication with words is logically impossible. This is the Lacanian explication of the classical communication difficulties. Besides that, though, this disjunction of impossibility goes much further. What Lacan is expressing here is nothing less than the illustrious “Il n’y a pas de rapport sexuel”, the non-existence of the sexual relationship. This statement, being already a very dense summary of a whole theory, is even more condensed here in the disjunction of the upper part of the discourse. Suffice it to say that the bridge between agent and other is always a bridge too far with, as an important result, the fact that the agent remains stuck with an impossible desire. This is important because it forms the basis of a particular social bond, characterising each discourse. Each of the four discourses unites a group of subjects through a particular impossibility of a particular desire.

Next, on the lower level, we find the disjunction of inability. This inability concerns the link between product and truth. The product, as a result of the discourse in the other, has nothing to do with the truth of the agent. If it were possible for the agent to verbalise his truth completely to the other, this other would respond with an appropriate product; as this precondition is not fulfilled, the product can never match what lies at the position of the truth.

If we want to depict these two disjunctions in a banal way, we’d better start with the opposite point of view, where the disjunctions would be abolished, the Sunday of Life (La dimanche de la vie), where the dreamt-of perfect communication and sexual relationship would be possible. In that case, the truth would find a complete expression in the desire of the agent for the other, thus realising the perfect relationship between those two with, as a product, the final satisfaction, embracing the truth. The necessary condition of this Hollywood scenario is that everything takes place outside the realm of the signifier, otherwise it would be structurally impossible. Once one speaks, one does not succeed in verbalising the truth of the matter with, as a consequence, the impossibility of realising one’s desire at the place of the other (“my place or your place?”), resulting in the inability of the convergence between product and truth.

As I already said, these two disjunctions are the most difficult and the densest part of the discourse theory. They condense a major Freudian discovery, namely the ever-present failure of the pleasure principle, and the consequences of that failure. This failure finds its expression in the disjunction of inability, whose consequence is impossibility. Man can never return to what Freud called “die primäre Befriedigungserlebnis”, the primary experience of satisfaction.4 He is unable to operate this return because of the primary splitting of the subject due to language. Nevertheless, he keeps on trying, and during this process he gets stuck on the road, and that is where he experiences the impossibility. Every biography can be read as a story about this impossibility.

Instead of bemoaning the typical human condition, it is much more important to understand the crucial thing about this impossibility, namely that it is only the upper layer of an underlying inability, and that the structure in its totality is a protective one. If we were able to return to this primary experience of jouissance, the perfect symbiotic relationship would be realised, which would imply the end of our existence as a subject. That is why the psychotic subject, who does not share the discourse structure, has to find a private solution to this ever-present danger of disappearing in the great Other.5

A normally divided subject is protected against this danger. To put it bluntly: on the road to the bliss of all-embracing jouissance in which we would disappear, we get stuck at the point of orgasm, which means the end of it, and then we can start all over again. Some people are even so afraid that they don’t even reach that point, and stop at an earlier roadblock.

In this sense, the four discourses are four different ways for the subject to take a stance towards the failure of the pleasure principle – that is the upper level, and four different ways to avoid the jouissance – that is the lower level. In that way, each of the four demonstrates a certain desire and the failure of it, resulting in a typical social bond. In order to understand this, we need to study the terms. The four positions and the two disjunctions always remain the same throughout the different discourses. The difference is situated in the terms, more particularly in the rotation of the terms over the positions. The terms themselves are very obvious, as they originate in the earlier Lacanian theory on the unconscious and the structure of language. We need at least two signifiers in order to have a minimal linguistic structure, resulting in two terms: the S1 and S2. The S1 being the first signifier, the Freudian “border presentation”, “primary symbol”, even “primary symptom”, has a special status. It is the master-signifier, trying to fill up the lack, posing as the guarantee for the process of covering up that lack. The best and shortest example is the signifier “I” which gives us the illusion of an identity of our own. The S2 is the denominator for the rest of the signifiers, the chain or network of signifiers. In that sense, it is also the denominator of “le savoir”, the knowledge which is contained in that chain.

The next two terms are both an effect of the signifier. Indeed, once we have two signifiers, the necessary condition for the introduction of a subject is fulfilled; remember: “a signifier is what represents a subject for another signifier”. So, the third term is the divided subject  . The last of the terms, last but not least, is the lost object, notated as object a.

. The last of the terms, last but not least, is the lost object, notated as object a.

In summary: the result of language acquisition is a loss of a primary condition called ‘nature’. From the moment you speak, you become a subject of language (a divided subject for that matter), who tries to grasp an object beyond language, or, more accurately, a condition beyond the separation between subject and object. This object represents the final term of desire itself; as it lies beyond the realm of the signifier and thus beyond the pleasure principle, it is irrevocably lost. In that sense, it constitutes the motor, which keeps us going forever. For Lacan, it constitutes the basis of every form of causality for us, humans.

The four terms — S1 and S2,  and a — are standing in a fixed order. These terms, with respect to the fixed order, can be rotated over the positions, resulting in four different forms of discourse. Indeed, with the fifth rotation, one returns to its starting point, due to the fixed order of the terms.

and a — are standing in a fixed order. These terms, with respect to the fixed order, can be rotated over the positions, resulting in four different forms of discourse. Indeed, with the fifth rotation, one returns to its starting point, due to the fixed order of the terms.

The first discourse is that of the master. It is the first one because it founds the symbolic order as such, presenting us with a formal expression of the Oedipal complex and the constitution of the subject. It is the discourse in which terms and positions seem to match. The agent is the master-signifier, pretending to be one and undivided. As Lacan puts it: it is that particular signifier which gives me the idea that I am (master of) myself: “maître/m’être à moi-même”. Indeed, the desire of this discourse is being one and undivided, that is why the master-signifier tries to join the S2 at the place of the other:

This desire is impossible: once there is a second signifier, the subject is necessarily divided between the two of them. That is why we find the divided subject at the position of the truth; the hidden truth of the master is that even he is divided.

In Freudian terms: the father is also submitted to the process of castration, the primal father is only a construct of the subject. The result of his impossible craving to be one and undivided through the use of signifiers is a mere paradox: it ends in the ever-increasing production of object a, the lost object.

This object a, cause of desire, can never be brought into relation with the divided being of the  . The effect is that the discourse of the master precludes the basic fantasy in its very structure:

. The effect is that the discourse of the master precludes the basic fantasy in its very structure:

a is not possible, the master is unable to assume this relation. That is why the master is structurally blind in this respect:

a is not possible, the master is unable to assume this relation. That is why the master is structurally blind in this respect:  // a. He cannot afford to acknowledge the imaginary part of his identity, as caused by the object a.

// a. He cannot afford to acknowledge the imaginary part of his identity, as caused by the object a.

One of the most interesting things about this discourse is the relationship between the master-signifier at the place of the agent and the S2 at the place of the other. This implies that knowledge is situated at the position of the other, which means that the other has to sustain the master in his illusion that he is at one with this knowledge. The pupils make the master or, in the Hegelian sense: it is the slave who confirms by his knowledge the position of the master.

A classic example, since the study by Jean Clavreul concerns the medical discourse.6 A medical doctor functions as a master-signifier, without any respect for his being divided as a subject; his division is situated underneath, as part of a hidden truth. In functioning as master-signifier, he reduces the patient to an object of his knowledge, and this shows in the terminology used, e.g. when referring to a patient as the “cardiac failure of room 16”. The net result of the discourse is the lost object, which means that the master will never be able to assume the cause of his desire, as long as he stays in this discourse. If he wants to do that, he has to turn to another discourse, but from that moment he is no longer able to function within the previous one. For example, one of my patients is an oncologist who had to interrupt his medical career the moment he was confronted with his father as cancer patient. At that moment, he was overwhelmed by his own being as a divided subject, confronted with an ever-receding truth; in his turn, he had to look for a master-signifier which would provide him with a satisfying answer. He had exchanged the master discourse for that of the hysteric and that is when he really started his analysis.

When we turn the terms one quarter forwards, we obtain the hysterical discourse. At the place of the agent, we find the divided subject, which means that the desire of this discourse is desire itself, beyond any satisfaction. The social bond of this discourse is what Freud described as the hysterical identification with an unsatisfied desire. A typical example can be found in The Interpretation of Dreams, i.e. the salmon dream of the wife of the butcher. The Freudian theory about this identification is written down in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego. Indeed, this phenomenon can give rise to a mass movement, which is always mass hysteria.

In this way, hysteria as a social bond puts the impossibility of desire to the forefront. This discourse, being the logical sequence to the discourse of the oedipal master, is at the same time the discourse of every normal neurotic. The moment one speaks, one has lost the primary object and becomes divided between the signifiers. The net result of that process is an ever-unstable identity and an ever-insisting desire, which can never be satisfied or destroyed, as Freud discovered at the end of The Interpretation of Dreams.

This desire, originating in the primary loss, has to express itself by way of a demand, directed to the other. In terms of discourse, one has to turn the other into a master-signifier in order to get an answer. Hence, the hysterical subject makes a master out of the other, an S1 who has to produce an answer:

When the hysterical students during the May revolt of 1968 interrupted the very seminar in which he was preparing the discourse theory, Lacan gave them a very cold answer: “Vous voulez un maître, vous l’aurez” (you are looking for a master, you will surely find one). It took them twenty years to understand.

The questions put to the master can be very different, but basically they are the same: “Tell me who I am, tell me what my desire is”. Tell me who I am as a man, a woman, as a father, a mother, as a daughter, a son. Although the master can be found in different places – (s)he could be a priest, a doctor, a scientist, an analyst, even a husband for that matter – they all have one thing in common: the master is supposed to know and to produce the answer. That is why we find S2, that is, knowledge, at the position of the product.

Sadly enough, this answer will always be beside the point. The S2 is unable to produce a particular answer about the particular driving force of the object a at the place of the truth:

This failure inevitably results in a never-ending battle between the hysterical subject and the master on duty, especially if the latter wants to keep his master-position. That is why revolutions always end with the installation of a new master, usually a bit more cruel and more harsh than the previous one, and that is why every master sooner or later ends up with his head in a place where it is not supposed to be.

Structurally, the hysterical discourse results in alienation for the hysterical subject and in castration for the master. The answer, given by the master, is always beside the point, because the true answer concerns object a, the forever-lost object, which cannot be put into words. The classical reaction of the master to this failure is to produce even more signifiers, which creates of course an ever-increasing distance from the lost object at the position of the truth. This in turn results in a confrontation between the master on the one hand and the fundamental lack in the signifying chain on the other, that is, the impossibility of the signifying chain to verbalise the final truth. This impossibility causes the failure of the master, and so his symbolic castration. In the meantime, the master at the position of the other as S1 has produced an ever-increasing S2 and thus a body of knowledge. It is this knowledge which determines time and again the fundamental alienation for the hysterical subject. As an answer to his or her particular question, (s)he receives a scientific theory, a religion, a…

Whether or not (s)he complies with it, i.e. whether or not (s)he identifies herself with it, is beside the point: in every case, the answer is an alienating one. The knowledge as a product is unable to say anything important about the object a at the place of the truth: a // S2. Throughout history we find grosso modo the following evolution:

| a | S1 | S2 | S |

| ? | priest | religion | saint or witch |

| ? | scientist | science | believer – cured sceptic – not cured |

| ? | analyst | psychoanalytic knowledge | good hysteric bad hysteric 7 |

The bonus is a growing body of knowledge. If we look at the history of science, we can interpret it as a hystory: science has always been an attempt to answer the existential questions, and the only result of that attempt is science itself … This is all the more clear in human sciences where, for example, even psychoanalysis is a product of hysteria; the same thing can be said of every development of knowledge, even on a strictly individual level. A developing subject wants to know the answers about his own division: that is why he keeps on reading, speaking etc. He will end up with a considerable body of knowledge, but that doesn’t teach him very much about his own lost object at the place of truth.

This knowledge takes the position of the agent in the university discourse. Indeed, if we turn the elements in the master discourse one quarter backwards over the four fixed positions, we obtain this university discourse, as a regression of the discourse of the master, and as the inverse of the hysterical discourse. The agent is the established knowledge; the other is reduced to being the mere object, cause of desire:

In the university discourse, the social bond results from the desire to reach the lost object through knowledge. This knowledge is presented as an accumulated, organised and transparent unity, coming straightforwardly to us from the textbooks. The hidden truth is that it can only function if one has a guarantee for it, a master-signifier.

Every field of knowledge functions by the grace of such a guarantee: for example, in our field, “Lacan has said that …” “Freud has said that …”. The primary example of this relationship between knowledge and master-signifier is Descartes, who needed God to guarantee the correctness of his science. A more recent example is Einstein, when he refused the implications of quantum mechanics with his “God doesn’t play with dice”.

At the position of the other, we find the lost object a, cause of desire. The relationship between this object and the signifying chain is structurally an impossible one. As the object is precisely that element, Das Ding, beyond the signifier, the signifying chain is the least appropriate agent for reaching for it. As a result, the product of this discourse is an ever-increased division of the subject. The more knowledge one uses to reach for the object, the more one becomes divided between signifiers, and the further one gets away from home, that is, from the true cause of desire.

In this discourse, there is no relationship between the subject and the master-signifier. The master is supposed to secrete signifiers without there being any relationship with his own subjectivity:

This implies one of the classical requirements of science: the so-called objectivity, which this discourse shows to be a mere illusion.

This brings us to the last discourse, that of the analyst, being the inverse of the discourse of the master. At the place of the agent, we find the object a, cause of desire. It is this lost object which founds the listening position of the analyst, which obliges the other to take his divided being into account. That is why we find the divided subject at the position of other:

This relationship between agent and other is impossible, because it turns the analyst into the cause of desire of the other, eliminating him as a subject and reducing him to the mere residue, even the trash beyond the signifiers. That is one of the reasons why Lacan stated that it is impossible to be an analyst, the only thing you can do is to function as such for somebody during a limited time. This impossible relationship from object a to divided subject is the basis for the development of the transference, through which the subject will be able to encircle his object. This is one of the goals of an analysis, “la traversée du fantasma”, the journey through the basic fantasy.

Normally – that is, following the discourse of the Master who sets the norm – the relationship between subject and object is unconscious and makes up part of the inability disjunction:  // a. The analytical discourse, being the inverse of that of the master, brings this relationship to the forefront in an inverted form. From inability it goes to impossibility, but it is an impossibility which can be explored in its effects (coined in seminar XX as “Ce qui ne cesse pas de ne pas s’écrire”, it doesn’t stop not being written).

// a. The analytical discourse, being the inverse of that of the master, brings this relationship to the forefront in an inverted form. From inability it goes to impossibility, but it is an impossibility which can be explored in its effects (coined in seminar XX as “Ce qui ne cesse pas de ne pas s’écrire”, it doesn’t stop not being written).

The product of this discourse is the master-signifier; in Freudian terms: the oedipal determinant particular for that subject. It is the function of the analyst to bring the subject to that point, albeit in a paradoxical way. The analytical position functions through a non-functioning of the analyst as a subject, his/her being reduced to the position of object.

This is the reason why the end result of the analytical discourse is radical difference. Beyond the world of make believe, “le monde du semblant” in which we are all narcissistically alike, we are fundamentally different. The analytic discourse yields one subject, constructing and deconstructing itself throughout the process of analysis; the other party is nothing but a stepping-stone. This process reminds me of several folk tales and fairy tales in which the beloved one, the object of desire, can no longer talk for one reason or another, so that the hero has to create a solution in which essentially he is confronted with his own being, unknown to him before.

The position of knowledge is remarkable in this discourse. One of the major turns in Freud’s theory and practice concerns precisely the way in which the analyst makes use of his knowledge.8 This is indicated by the discourse of the analyst and it is quite paradoxical:

The knowledge functions at the position of the truth, but – as the place of the agent is taken by object a – this knowledge cannot be brought into the analysis. The analyst knows, oh yes, he does know, but he can’t do much with it, as long as he takes the analytical stance. That is why this knowledge can be expressed by the idea of Docta Ignorantia, i.e. “learned ignorance” as it was called by Nicholas of Cusa in the fifteenth century. The analyst has wisely learned not to know, and this opens up a way for the other to gain access to that which determined his or her subjectivity.

The four different forms of discourse are four different social bonds, each time based on an impossible desire. This brings to mind the Freudian formula about the three impossible professions, “Edukieren, Regieren und Analysieren”; to educate, that is the university discourse, to govern, the master discourse, and to analyse, the analytic discourse, each giving rise to a particular brotherhood.9 Freud forgot the most obvious one, the one that holds us together on a mass scale, namely to desire. What I did not describe are the interrelations between the four forms, and the way each discourse topples over into another. As this is material for another lengthy paper, suffice it to say that this interchange has everything to do with the two disjunctions: the disjunction of impossibility of one discourse gives rise to the disjunction of inability in another, and so on.

In my introduction, I stressed the usefulness of this theory. Its formal character makes it possible to use it in many different particular instances. Nevertheless, in my experience, the greatest danger is that of reducing each discourse to one concrete implementation. The discourse of the hysteric, then, would be the way a neurotic person interrelates to someone else – very annoying; the discourse of the master would be synonymous with a kind of aristocratic narcissistic authority – always suspect; the discourse of the university would be the babbling of teachers – extremely annoying; and the discourse of the analyst would be the true and only one, leading to paradise – very expensive.

Besides the epitheta ornantia, these implementations are fundamentally wrong. The discourses, existing as a formal structure even before one speaks, are continually interchanging through the interrelationships between their disjunctions. The reduction to one implementation is a fortiori a reduction. Let us take the hysterical subject as an example. He or she can come to the consulting room with a typical hysterical discourse, in which the other is forced to take the position of the master, with the obligation to secrete knowledge and end up castrated. On the other hand, the same hysterical subject can appear on the scene with the discourse of the master – and that is not such an unusual situation. In that case, the patient identifies him or herself with his or her symptom as master-signifier S1 about which the other functions as a guarantee because he is supposed to possess the knowledge about it. “I have a postnatal depression, I am my postnatal depression, you are the specialist who knows (S2) about such things, so just go ahead and cure me, do anything you want, as long as I don’t have to enter the game as a subject”. Thirdly, the same hysterical subject can come to us with a university discourse. He or she can impress us with a considerable sum of knowledge by which he or she reduces the other to a mandatory silent object, and by which he or she avoids looking at the hidden master at the position of the truth.

Just as the reduction of hysteria to the hysterical discourse is wrong, the same goes for every discourse. As the truth can only be half said – “le mi-dire de la vérité” – the wheel keeps on turning. In the second chapter of his seminar Encore, Lacan tells us that, each time one changes one discourse for another, there is at that moment an emergence of the analytic discourse, as a possibility for grasping the determination from object a to  . In the same paragraph he tells us that every crossing of discourse is also a sign of love. As knowledge stops there, it is appropriate to stop this paper at this point as well.

. In the same paragraph he tells us that every crossing of discourse is also a sign of love. As knowledge stops there, it is appropriate to stop this paper at this point as well.

1. Lacan, J.(1993). The Seminar of J.Lacan: Book III. The Psychoses 1955-56. Edited by J.A.Miller, translated with notes by R.Grigg. New York, Norton, p. 15.

2 As we consider this theory to be a condensation of Lacan’s evolution, every bibliographic reference to his work is too limited. The theory itself was coined during the seminar of 1969-70 (Le Séminaire: Livre XVII. L’Envers de la psychanalyse. Texte établi par J.A.Miller. Paris, Seuil). See also Radiophonie (In Scilicet, 1970, nr.2/3, pp. 55-99) and the next seminar: D’un discours qui ne serait pas du semblant. A further elaboration can be found in Encore, his seminar of 1972-73, translated as The Seminar of J.Lacan: Book XX. On Feminine Sexuality, the Limits of Love and Knowledge. Edited by J.A.Miller, translated with notes by B.Fink. New York, Norton, 1998.

3 Freud, S. (1917a). A Difficulty in the Path of Psycho-Analysis. S.E. XVII, pp. 139-43; The Resistance to Psycho-Analysis (1925e). S.E. XIX, p. 221.

4 Freud, S. (1887-1892). Project for a Scientific Psychology. S.E. I, pp. 317-320. This idea persists through the whole of Freud’s work.

5 That is why the psychotic patient is uncanny to us: we do not share the same social bonds, because the psychotic does not share the discourses, due to his solution of the Oedipus complex – a solution that lies outside the discourse of the master, and hence, outside the very structure of discourse.

6 Clavreul, J. (1978). L’ordre medical. Paris, Seuil, pp. 1-284.

7. The expressions “good or bad hysteric” were naïvely coined by E. Zetzel in her paper “The so-called good hysteric” (In Int. J. Psychoanal., 1968, 49, pp. 256-260). The difference between the hysteric as a saint or a witch was not naïvely described by G. Wajeman’s Le maître et l’Hystérique (Paris, Navarin/Seuil, 1982).

8. I have described this evolution in Freud as an evolution in discourses, starting with the hysterical discourse, via the discourse of the master to the analytical discourse: Verhaeghe, P. (1999). Does the woman exist? From Freud’s Hysteric to Lacan’s Feminine. New York, The Other Press, revised second edition.

9. Freud, S. (1937c). Analysis Terminable and Interminable. S.E. XXIII, p. 248.