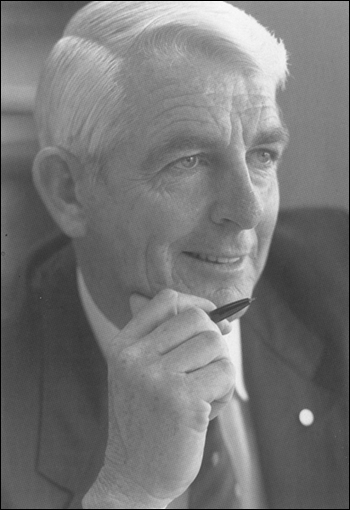

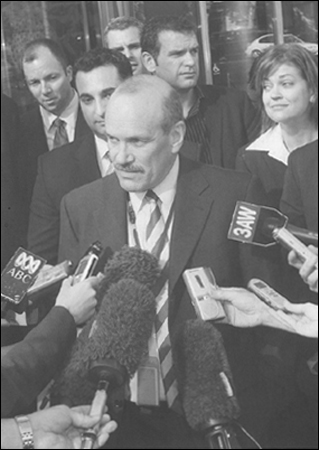

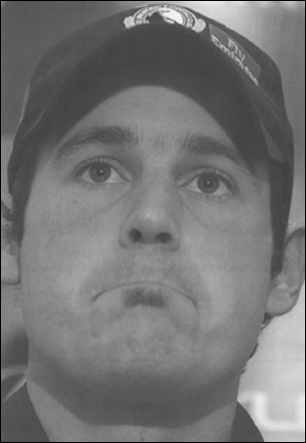

Don Hancock: Former Western Australia police crime chief, killed in bikie bombing after a mystery shooting on the goldfields.

If they were not outlaw bikies many would be just overweight, middle-aged men with no career prospects, few life skills and chronic body odour …

THE bikies had every reason to hate Don Hancock. They knew the former senior Perth detective turned country publican had shot dead a Gypsy Joker member called Billy Grierson after a minor dispute in October 2000.

By the time police got to Hancock he was showered and changed. The stickler for police procedure refused to hand over his original clothing, defied instructions to stay at the scene and then ate an orange to remove gunshot residue.

Investigating police believed Hancock was the sniper who shot Grierson that night in the West Australian goldfields town of Ora Banda.

The Gypsy Jokers believed Hancock, former head of the CIB, was not charged because the reputation of an ex-policeman was more important than a bikie’s life.

They vowed revenge – and then went to war. They repeatedly bombed Hancock’s pub and home – concealing the explosives before one attack in the coffin of a teenage boy.

Hancock – known as the Silver Fox – knew he was a marked man and returned to Perth where a state-of-the art security system was set up in his home.

Although retired he was allowed to carry a handgun because of the constant threat to his life.

But video cameras and a .38 revolver would never be enough to protect the 64-year-old former policeman.

For months the bikies tried to follow Hancock without getting close enough to kill him but they soon found his weakness. The former old-school copper was a creature of habit who regularly went to the races with a mate, retired bookie Lou Lewis.

When Gypsy Jokers were leaked the details of the bookie’s car by a tame source within the WA Transport Department the rest was easy.

Gang members strolled around the Belmont Park racecourse until they found Lewis’ unlocked car and then gently slipped a bomb under the passenger seat.

As the two men drove home on September 1,2001, one of the bikies used a mobile phone (as terrorists often do) to trigger the ammonium nitrate bomb, muttering ‘Rest in peace, Billy’ before the bomb detonated, obliterating both victims.

The explosion was heard more than eight kilometres away. The ramifications would last for years.

Don Hancock was their enemy but Lou Lewis was not involved. To the bikies he was just acceptable collateral damage.

Welcome to the world of outlaw motorcycle gangs, where violence is often the first and only resort.

ON June 18, 2007, as Melbourne’s morning rush was peaking, behind closed doors in the so-called entertainment district centred on King Street, some were still coming down from the night before.

A stripper from Spearmint Rhino, Autumn Daly-Holt, was dancing provocatively next door in Bar Code. Then she was bashed savagely, allegedly by a member of the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang.

The bikie, Christopher Wayne Hudson, was alleged to have then jumped in a taxi with another stripper, Kaera Douglas, 24. As they argued the cab pulled up at the corner of Hinders Lane and William Street.

Witnesses said a man, later identified as Hudson, tried to drag her from the car.

Two men, solicitor Brendan Keilar, 43, and Paul de Waard, a 25-year-old Dutch backpacker, tried to step in. Keilar was shot and died in the street. De Waard and Douglas were also shot and seriously injured.

Witnesses said the gunman hesitated then pointed the gun under his own chin as if considering suicide. But self-preservation instincts over-rode the impulse and he dumped the gun before escaping.

The obscene violence that morning graphically exposed what happens when Melbourne’s underbelly of guns, drugs and vice collides with the mainstream world on a busy city street.

And while the rampage cannot be blamed on the Hell’s Angels – it appeared to be a domestic dispute gone mad – it raises questions about the bikie culture and the community’s response to the ever-present threat.

The Australian Crime Commission says there are seventeen outlaw motorcycle gangs in Victoria, and 35 throughout Australia, with a total of 3500 fully-patched members and perhaps as many again who are associates.

The ACC is investigating bikie groups as established criminal networks, and has connected them with prolific money laundering, tax fraud, firearms trafficking and drug manufacturing.

The commission has found that the ‘size, profile, geographic spread and level of sophistication of OMCG (outlaw motorcycle gangs) criminal activity presents a significant threat to Australia and its interests’.

It says gangs infiltrate legitimate business enterprises, ‘including finance, transport, private security, entertainment, natural resources and construction’.

There is nothing subtle about outlaw bikies. While many gangsters try to conceal their underworld connections behind closed penthouse doors, bikies wear their colours to show their criminal spots.

It is a deliberate strategy designed to forge military-style loyalty between members while simultaneously intimidating outsiders.

Some brag they are like a swarm of bees that will attack (and die) to protect the hive.

The analogy has some substance. Most of the bikies are like worker bees. They do not share in the massive profits but get their identity from the collective.

If they were not outlaw bikies many would be just overweight, middle-aged men with no career prospects, few life skills and chronic body odour.

But those who rise to run the clubs often have affluent lifestyles and manage to run successful businesses – suspected of being fronts to launder drug money. Bikies have also moved into debt collecting, using their fearsome reputations to stand over parties in civil disputes.

They have been known to wear their gang colours to auctions – a move designed to intimidate rival bidders.

The outlaw bikie world remains in a constant state of tension, with smaller clubs at risk of violent takeover by the Hell’s Angels, Bandidos, Rebels, Outlaws, Black Uhlans and Nomads.

Police in Sydney are facing bikie violence as gangs battle to gain control of the lucrative nightclub drug scene. In the same week as the Melbourne CBD shooting a bomb exploded outside a Hell’s Angels clubhouse in Sydney. Similar battles have broken out in Queensland.

Unlike the Melbourne underworld war, in which victims were shot in ambushes, the Finks and Hell’s Angels went to war within a crowd of 1600 people at a kickboxing event on the Gold Coast.

In Geelong the Rebels’ headquarters were firebombed in April 2007 and the Bandidos’ clubhouse was sprayed with bullets.

Earlier that month two gunmen shot four Rebels gang members in an Adelaide nightclub.

Police say outlaw gangs in Australia have been bullying their way into nightclub ownership, club security, strippers, entertainment, modelling agencies and prostitution. They have attempted to buy a legal brothel using associates with no criminal records as a front.

In Melbourne, while bikies do not appear to own nightclubs – at least on paper – police intelligence shows gang associates own, run and control security at some venues.

Police say rival bikie gangs are trying to gain control of security at popular venues so they can green-light the distribution of their drugs through sanctioned dealers.

‘Control the front door and you control who gets in. Control who gets in and you control the distribution of drugs,’ according to one veteran investigator.

In Victoria, bikie headquarters are easily identified and heavily protected.

The Special Operations Group has used bulldozers, a ram truck and explosives to gain access. In Western Australia special anti-fortification laws have been passed to try to stop bikies building domestic forts in Perth.

In the 1980s an Australian Bureau of Criminal Intelligence investigation into bikies codenamed Wingclipping found the gangs to be a serious organised crime threat.

And the problems have only escalated in the past two decades. In Angels of Death: Inside the Bikers Global Crime Empire, Canadian experts William Marsden and Julian Sher say Australia has the highest number of bikies per capita in the world.

Marsden and Sher found that since the mid-1990s Australian bikies have been locked in a decade-long battle to control their slice of the massive drug market. ‘Over the next five years, 32 bikies would die and many more would be beaten as the Hell’s Angels, Bandidos and other clubs fought over the amphetamine trade.’

In fact it was in the mid-1970s that the Hell’s Angels pioneered the trade in Australia – and first established the international nature of Bikie Inc.

PETER John Hill was not an average bikie. The former private school boy and son of a bank executive loved motorbikes and became an original Melbourne Hell’s Angel.

Hill became friendly with senior Californian Angels, including hitman James Patton ‘Jim Jim’ Brandes.

When Hill visited the Oakland Chapter, Brandes took him to prison to meet the gang’s amphetamine expert – Kenny ‘KO’ Walton.

Walton told Hill how to make speed and later mailed him a detailed recipe. In return Melbourne Hell’s Angels organised to smuggle a vital ingredient for amphetamine production to the US gang.

At the time the chemical P2P was difficult to source in the US but remained freely available in Australia.

Hill and his team filled three-litre Golden Circle pineapple tins with the chemical and mailed them, two at a time, to the Oakland chapter.

After 50 deliveries the Californian gang had sufficient to make $US50 million in speed.

Bob Armstrong was the Victorian policeman who would spend half a career in investigations, surveillance and undercover work that centred on the bikies. His original team smashed the Hell’s Angels Greenslopes amphetamines lab in 1982, finding three kilograms of speed, cash, handguns and a machine-gun.

Later he received a call from Peter Hill’s mother, Audrey, telling the detective that a US hitman was on his way to kill him.

The suspect was grabbed as he walked from his plane into Melbourne Airport.

It was ‘Jim Jim’ Brandes, who had previously seriously injured an American detective after setting off a bomb next to the policeman’s car.

Peter Hill later fell out with the Angels and in an act of revenge he sold the original speed recipe to a rival gang for just $1000.

That gang was the Black Uhlans, whose founding members included the ambitious John William Samuel Higgs, later to become the biggest speed producer in Australia.

Higgs was in constant trouble with the police as a teenager, with his first conviction recorded at thirteen. He later gathered convictions as varied as manslaughter and the illegal possession of a stuffed possum.

Higgs was to become wildly rich and showed his gratitude to his gang by donating its Melbourne clubhouse. In return he was made a life member.

Higgs was the target of eight National Crime Authority, federal and Victorian Police operations from 1985, including Australia’s longest-running drug investigation, codenamed Phalanx. This eight-year inquiry led to the arrest of 135 people and the seizure of chemicals with the potential to make speed valued at $200 million.

The money made by select bikies places them squarely on the A-list of crime.

The investment portfolio of some gangs is vast.

Police say some have invested heavily in natural resources, including Australian mining and Indonesian oilrigs.

One illiterate ex-labourer and former bouncer known as the ‘Maltese Falcon’ controlled a real estate portfolio worth $3.3 million, 70 motorcycles and two Rolls-Royces. Bikies have also infiltrated government departments to access confidential computer records.

Investigating hardcore bikie gangs is notoriously difficult. They are usually security conscious, rarely trust outsiders and use expendable ‘hang-arounds’ and ‘prospects’ to complete low-end criminal activities.

They often have signs plastered on phones to remind them they may be bugged – although recently several forgot and used the phone to try to organise a quick insurance scam. The slipup resulted in a successful prosecution.

They also have professionals electronically ‘sweep’ their clubhouses after police raids looking for listening devices. Routinely police find hot leads peter out when witnesses go cold.

A tow-truck driver who removed a bikie’s vehicle seized by police was later bashed. A safe expert who opened a bikie safe after a police raid found his business badly damaged by fire.

One man who made a statement against a bikie was at first forced to move from Melbourne, and when he was threatened with a one-way trip to the cemetery, fled the country never to return.

One man who woke up in hospital after being tortured told police he had no idea what had happened.

Victoria’s Chief Commissioner Christine Nixon defended the police response to bikie crime by saying the problem was greater in some other states.

‘We are, in fact, working on these different bikie gangs. We are part of a whole national approach working on these bikie gangs.’

But some police disagree. The specialist bikie unit in the organised crime squad has been closed during a restructure. Some senior members of the crime squad want the decision reviewed.

It is difficult but not impossible to infiltrate bikie groups. Ten years ago two Victoria Police codenamed Wes and Alby went undercover for thirteen months to infiltrate the Bandidos as part of a secret operation codenamed Operation Barkly.

Alby and Wes were involved in more than 30 deals buying marijuana, amphetamines, LSD and ecstasy from Bandidos in three states.

They were so trusted that Alby became the secretary-elect for the Ballarat chapter, giving him access to the club’s financial records.

Police eventually arrested twenty bikies as a result and uncovered plans for the gang to open nightclubs in Geelong and Ballarat as fronts for drug dealing.

Operation Barkly was closed because of the danger to the undercover police. During the investigation three Bandidos, including president Michael ‘Chaos’ Kulakowski, were murdered.

Bikies pride themselves on protecting and dealing with their own, but there is a limit.

The suspect in the CBD shooting was cut loose by the gang and had no choice but to surrender.

Hudson gave himself up after his lawyer negotiated a deal with a ‘trusted’ senior detective.

After two days of fruitless efforts to find him the breakthrough came when Northcote solicitor Patrick Dwyer contacted Detective Inspector Kim West, of the major crime investigation unit.

Hudson was frightened he would be intercepted and killed by police as he left his country hide-away to drive to a designated police station.

The first sign that Hudson had no alternative but to give himself up was when a Queensland lawyer who previously represented the suspect rang the homicide squad to say he could no longer act for him as it conflicted with the interests of his existing clients – the Hell’s Angels.

The lawyer knew Hudson well. That’s because Hudson had been involved in a vicious public gun battle in Queensland the previous year between the Finks and Hell’s Angels gangs – but that time he was a victim.

He was shot in the jaw and back in the riot between bikies in the crowd at a kickboxing show at the Royal Pines Resort at Southport in March.

Three people were shot and two stabbed. Four were bikies, and the fifth was a teenager caught in the crossfire.

The fight was allegedly sparked by Hudson’s defection from the Finks to the Hells Hell’s Angels and by him encouraging others to follow.

The Angels recruited Hudson because of his links to local nightspots. He later moved to Sydney where he established new connections in the nightclub industry before he landed in Melbourne.

He had strong connections with bikie chapters in Queensland, Sydney, Adelaide and Melbourne but after the CBD shootings those links were severed.

Less than 48 hours after the shootings police were told the Hell’s Angels had persuaded the suspect to give up. Whether the decision was a moral one based on what he was alleged to have done – or a practical one because the gang knew that while the suspect was at large they could expect to be the focus of an intense investigation – is largely irrelevant.

It was the right result.

Just after 4.30pm on June 20, Hudson was driven to the police station at Wallan, in Melbourne’s north, from a safe house where he had been hiding.

He was unarmed and had suffered a badly damaged left wrist courtesy of a self-inflicted wound that would require plastic surgery.

Turning himself in means Hudson’s fate will be decided under due process. Due process means an accused’s guilt or innocence is decided by a jury selected from the broader community.

This suspect is perhaps lucky to have avoided judgement by his peers in the bikie world.

But the story of Christopher Wayne Hudson and his involvement in Melbourne nightclubs began six days before the CBD shooting, due to a meeting with a Collingwood footballer who was looking for adventure.

THE luckiest drunken footballer in Australia is not Alan Didak, whose close encounter with the Hell’s Angels could have been life-threatening as well as career-ending, but his day-time opponent and night-time drinking mate, Melbourne’s Colin Sylvia.

Even the sight of naked women dancing in the King Street strip club Spearmint Rhino was not enough to keep Sylvia awake.

Fatigued from a hard game of football on June 11, 2007, and a harder night of drinking, he slowly descended into alcohol-induced unconsciousness.

Drunk and asleep, Sylvia was gently evicted by bouncers without incident. (A few days later he was quoted without a hint of irony as saying the mid-season break was an ideal opportunity to relax his mind and body.)

Without his football mate, Didak accepted a lift from Christopher Wayne Hudson, the man who would later stand accused of the Melbourne CBD shootings.

Didak’s decision, the subsequent police investigation and the football club’s initial farcical response, left many holes in the story that began as a drunken adventure and ended in allegations of gunfire.

For Melbourne and Collingwood, the Queen’s Birthday match that day was the perfect punctuation mark for the mid-season break.

With no game scheduled the following week, the players had one of their few in-season opportunities to slip the AFL’s tight lifestyle leash and head out on the town. But the idea of a few beers soon turned into a binge of mixed drinks and straight spirits as a group of players headed from nightclubs to strip clubs.

Eleven years earlier the previous Collingwood coach, Tony Shaw, banned his players from King Street bars, but that rule, like many others, had been quietly shelved.

After drinking at several venues, Melbourne and Collingwood stayers, including Didak and Sylvia, descended to the Bar 20 strip club.

While the other footballers drifted off, Didak and Sylvia tottered up King Street to Spearmint Rhino.

Drinking vodka, lime and sodas and straight shooters, they were flying by the early hours of Tuesday.

The last thing Didak needed was another drink but unwisely he accepted one – this time a bourbon and cola – from a heavy-set man with burning eyes who said he was a fan of the Collingwood forward.

With Sylvia having lost interest and heading for the comfort of his bed, Didak chatted with the fan, who had recently moved from interstate.

The supporter, Christopher Hudson, followed two clubs. One was Collingwood and the second was the Hell’s Angels.

But Didak’s ability to judge the situation was severely affected by hours of drinking and he apparently saw no signs of danger from the man he had just met.

Some time after 3am, the two left, Didak slipping into the passenger side and Hudson behind the wheel of the bikie’s powerful black Mercedes-Benz.

Didak would later tell police he had accepted an offer of a lift home to Kew when it all went horribly wrong. It is a version of events that detectives found harder to swallow than a free bourbon and Coke.

The football club’s spin initially suggested Didak was a victim who wanted to head home but was virtually abducted and driven to the Hell’s Angels East County headquarters in Campbellfield.

Supposedly terrified, he asked to be driven home, only to be embroiled in a shooting incident and a dangerous high-speed trip before being dropped in the city shaken – but not stirred enough to contact police.

‘While in the car the person insisted that Alan accompany him to a bikie gang clubhouse. Alan felt he had no choice but to comply,’ a poker-faced Collingwood chief executive Gary Pert told the media when the story finally broke after the CBD tragedy and Hudson’s subsequent arrest.

Police suspect, but can’t prove, that Hudson, 29, bragged that he was a Hell’s Angel and invited Didak to the headquarters.

The footballer, curious to see inside the heavily fortified premises, accepted, an act that, while foolhardy, was not illegal.

It was only minutes after they left the strip club that Didak realised his night was going off the rails. Police allege that as the Mercedes sped over the Bolte Bridge, a high-powered handgun was produced and several shots were fired from the window.

Speeding along the Tullamarine Freeway, they arrived at the bikie headquarters around 4am.

Didak, 24, was greeted by at least one other member of the chapter. (Bikies rarely leave their headquarters vacant at any time to deter other gangs from raiding the property and police from breaking in to hide bugs.)

If Didak was terrified, he hid it well. When he was offered yet another drink, he accepted and stayed for up to 45 minutes before hopping back in the car, this time in the back seat of the coupe.

Two men sat in the front.

They sped off, flying through a red light across the Hume Highway just as a local police divisional van cruised past.

The police followed, but the Mercedes slipped into the Scania trucking industrial estate, out of sight, where it might have stayed if not spotted by an early-morning worker. It then cruised slowly out of the factory complex and stopped in Northbourne Road.

The police, having spotted the car, pulled up about 50 metres behind. Several shots allegedly were fired from the driver’s side window of the Mercedes before it sped off again.

Police did not give chase. If they had, Didak might well have been permanently delisted, courtesy of a police bullet or a high-speed car crash.

Later police would find ten spent shells and one live one on the ground in two separate places on Northbourne Road – meaning someone in the car fired a volley of shots before slipping into the estate and a second set when the police pulled up behind.

Because of the pressing danger of a gunman on Melbourne streets who was prepared to fire shots at police to avoid arrest, the investigation was immediately handed to the experts, the armed crime task force.

A police appeal that morning brought an immediate response through Crime Stoppers.

One caller reported a black Mercedes speeding wildly down the Tullamarine Freeway to Melbourne with one man in the back leaning forward and talking to the driver.

Detectives traced the Mercedes to a luxury vehicle dealer who at first denied any connection with Hudson. But detectives found the name of a Sydney woman who was alleged to have bought the car. She had once worked at Spearmint Rhino and knew Hudson.

Within 48 hours of the shooting police were looking for Hudson but they did not know where he was living and still did not have enough evidence to make an arrest.

Six days after the alleged shooting spree, Hudson is alleged to have opened fire in the city with tragic consequences.

The first police knew of a link between the footballer and the suspect was when they went to Hudson’s apartment and found a handwritten note with Alan Didak’s name and phone number.

A homicide detective and another from the armed task force quietly visited Didak away from the club to ask him some informal questions.

They gave him a few days to think deeply before he was to be formally interviewed.

But as rumours of Didak’s involvement started to circulate in football-mad Melbourne, the interview was pushed forward, to be held discreetly at the Boroondara police station rather than at the St Kilda Road crime headquarters on June 28 – 10 days after the CBD shooting.

But the media were waiting. It was the lead item on TV news and made page one the following day. Didak gave police a version of events.

In some parts it was clear and in other parts strangely vague. He can remember the events at the strip club, the drive to the clubhouse, shots on the Bolte Bridge, drinks with the Hell’s Angels and the dangerous trip back to the city. He can even remember leaning forward asking the driver to slow down on the freeway (an act independently corroborated by the Crime Stoppers call).

He was lucid enough when dropped at Flinders Street to even ask police in a passing van if they could give him a lift.

In the brief discussion he failed to mention his close encounter with the bikies.

The police declined the opportunity to act as an AFL shuttle service and Didak grabbed a cab.

Yet, when finally interviewed by detectives, Didak suffered a memory lapse that blanked out the crucial ten minutes when the shots were allegedly fired in the vicinity of police.

Perhaps he passed out – a convenient but entirely possible scenario considering the amount he had drunk.

No-one would really know whether Didak was asleep as Hudson isn’t talking and the other passenger in the Mercedes is yet to be identified.

But what Didak did not know was there was another witness – not a person with a faulty memory, but a video camera.

When the driver of the Mercedes slipped into the Northbourne Road industrial estate to avoid police, a security camera filmed three men in the car, with the rear passenger conscious and clearly animated.

There is no doubt that after the event Didak was terrified. He feared the Hell’s Angels, a group with a reputation of hunting down and silencing potential witnesses.

But Didak was safe. The Angels had turned on Hudson. He was on his own, whereas Didak had Collingwood.

Police briefed senior Collingwood officials on their investigation but were staggered when they saw how the player was initially portrayed as an innocent victim.

‘He is not a suspect, he is not a victim, he is a witness and not a very good one,’ a senior policeman said.

At the same time, police say suggestions that if Didak had come forward the CBD shooting may never have happened are unfair to the footballer, who on the known evidence was guilty only of being a fool and then remaining silent on the grounds of self-preservation.

But how silent? Police believe he did tell some team-mates, including those he was drinking with that night, what had happened after they had left.

Just hours after the Campbellfield incident he was on a plane to Queensland with the team. Collingwood staff hastily briefed club president Eddie McGuire as he was about to fly back to Australia from Europe.

But when he returned he quickly saw the club’s position as untenable. Increasingly uncomfortable with what he saw as a less-than-comprehensive briefing, he shifted the position from victim Didak to last-chance Didak.

Far from Didak being an innocent caught up in events as first portrayed, McGuire now says, ‘he was out too late, met bad people and it was just stupid’.

Later McGuire said Didak would have faced the sack if he had not shown remorse and that the footballer would only remain at the club if he accepted a nightclub and alcohol ban and a lam curfew.

Meanwhile, Chief Commissioner Nixon provided some unlikely support for Didak. ‘I think it has been quite amazing to watch how he has been treated in the media. I think, as a young man, he’s under enormous pressure and in some ways he’s been damned without people really understanding what might be the circumstances,’ she told 3AW.

Of course, the young police who were stopped in their tracks when shots were allegedly fired at them in Campbellfield would have also felt a touch of pressure before the Mercedes sped off.

At yet another Collingwood press conference, the slant that Didak was a victim was finally dumped.

With Eddie McGuire now in the driving seat, the player fronted the media to say his actions were ‘reckless, embarrassing and stupid’ and had damaged his reputation.

‘I understand if I don’t comply (with the restrictions) that is’ the end of my career at Collingwood,’ he said.

Collingwood was worried its brand was being damaged. Its first Didak news conference was held with sponsors’ logos visible. They were removed for subsequent briefings.

The Hell’s Angels had a similar worry earlier in 2007 when they expelled a senior member. They solved the brand issue by removing the former member’s Hell’s Angels tattoos – with a steam iron.

AFTER he fired the shots that killed Brendan Keilar and wounded two others, the gunman placed the pistol barrel under his chin. For a moment, he seemed set to kill himself, but he lost his nerve and ran.

If he had pulled the trigger, it would have blown his head off. It’s that sort of gun.

A court will formally decide who carried out the shootings but the handgun is already guilty. It is illegal in Australia on two counts: It combines a brutally heavy calibre with a short barrel that makes it easy to hide, a recipe for carnage in criminal hands, and it is a product of a sinister black market that, like the drug trade, ran out of control while authorities concentrated on easier targets.

‘A highly concealable heavy hitter’ is how one disgusted licensed gun dealer describes the weapon used to kill the heroic Melbourne lawyer, wound the equally brave Dutch backpacker and then injure an exotic dancer.

Overseas, such a pistol is used by ‘narcotics agents, undercover cops and bodyguards’, the dealer says. And gangsters, of course.

In Australia only an underworld enforcer or the dangerously deluded – or both – would carry such a man killer, more powerful than Victoria Police service revolvers. The pistol that blighted so many lives was found at a city building site soon after the shootings.

It was a .40 calibre Llama Minimax. It is small, relatively light and yet, with its hefty calibre, all too deadly.

Its stubby barrel is not made for accuracy – to hit targets or hunt – but to blow a hole in humans at murderously close range.

A few years ago, a handgun like that, or its Chinese equivalent, would have brought between $1000 and $2000. But the black market is so turbocharged by drugs, money and paranoia that it could bring much more now.

The word on the underworld rumour mill is that the city gunman paid $5000 for the murder weapon less than two weeks earlier.

For something that can destroy a life with such awful efficiency, the Llama is a relatively crude tool.

Not quite, perhaps, the ‘gangster junk’ that purists might label it, but so poorly thought of by legitimate target shooters that no dealership sells Llamas in Australia, and few were ever imported in the past.

The murder weapon almost certainly reached Australia through an underground network as pernicious as the drug trade – and inextricably entwined with it.

In the dog-eat-dog underworld, drug money and gun violence go together. Melbourne’s underworld war proved that.

The path that ended with death in William Street began at a factory in northern Spain, the Basque region that has produced terrorism for decades and cheap pistols for much longer. For most of the twentieth century the area boasted three pistol-making plants, mostly making copies of American brands Colt and Smith & Wesson.

One factory, run by the Gabilondo Y Cia company, made pistols at Vitoria until 2003, when it moved to Legutiano under a new name, Fabrinor.

Arms dealers sell to whoever buys. In 1943, the firm supplied’ the Nazis in German-occupied territories with thousands of specially badged pistols.

After the war it found new markets, including a niche for a two-shot ‘pistol’ disguised as an office stapler, which authorities feared would be used by terrorists.

From the mid-1990s until it closed in 2005 the firm was making 20, 000 pistols a year, with 17, 000 a year going to the gun-hungry US.

It is almost certainly one of these that shot Brendan Keilar and the other two victims in Melbourne.

So how did it get here? While it’s possible the pistol was exported to the Philippines and then smuggled here by light plane or small boats through Papua New Guinea, Timor or the Pacific Islands, it is far more likely it came via America.

It was probably bought there as part of a job lot for as little as $US400 ($A470) new or even $US200 second-hand. And it’s likely the buyer was fronting for an outlaw bikie gang with a proven smuggling route all fixed.

Don Hancock: Former Western Australia police crime chief, killed in bikie bombing after a mystery shooting on the goldfields.

Every dog has its day: Carl Williams in happier times, when he gave the press conferences and the police said ‘no comment’. It didn’t last.

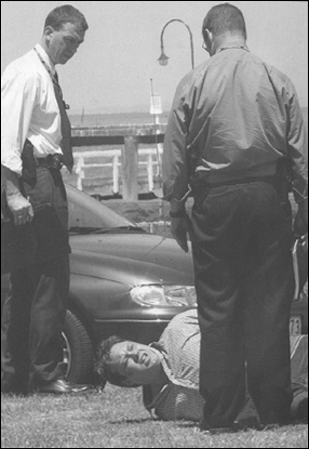

Cop this: The day the man behind the gangland killings found the tide had turned against him.

Purana task force members led by dogged detective inspector Gavan Ryan (centre) just after Williams had been sentenced to 35 years. This time, police held the press conference.

Too late for shoosh: Carl Williams’ fiercely loyal mother Barb with the drug dealer’s then latest glamour puss. May be the girl was just wagging school.

What’s the story? Carl Williams is a fat drug dealer who won’t be out of jail before he’s 71, if he lives that long. Yet this young woman turned up at court daily to support him. Go figure.

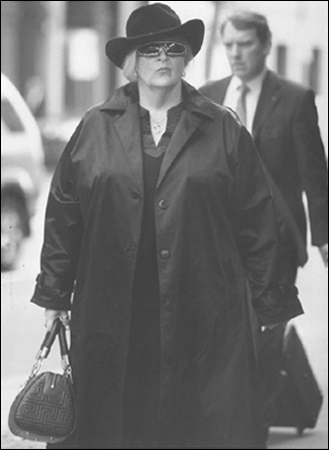

Black widow: An angry Judy Moran rolls into court in boutique mourning clothes to see Carl Williams sentenced. Her late son Jason had put holes in his manners, and Williams’s belly, with a .22 pistol.

Unhappy: Roberta Williams (far right, in the cap) expresses her displeasure to her chubby hubby’s new buxom best friend.

You’ve got to be kidding (1): What could be the last photograph of Carl Williams, taken in court moments before Justice Betty King sentenced him to a minimum 35 years jail. He stopped smiling then.

You’ve got to be kidding (2): Ben Cousins’ bizarre statement to camera in which he admitted but failed to explain his involvement with drugs, at the same time wearing a garment rejected by Miami Vice. Go figure.

Rehab West Coast style: Ben Cousins with unidentified female who may or may not be a drug counsellor.

Collingwood footballer Alan Didak on a different type of bike. He lived to regret his night out with a Hells Angel.

I’m no Angel: Alan Didak faces the media to speak about his drunken adventures with outlaw bikie gang members. His memory was shaky.

Didak searches his memory. Only two things are known: Shots were fired, and there were holes in his story.

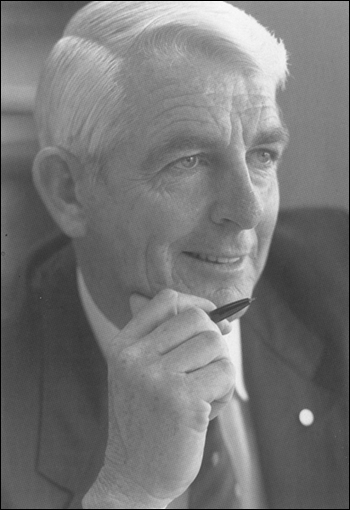

Hudson after his arrest: Gave himself up after gentle persuasion from Hells Angels.

Christopher Wayne Hudson: Alleged CBD killer, former Fink and Hells Angel gang member, keen Collingwood supporter.

Outlaw bikies are known for trafficking amphetamines. But their link with guns goes back further and runs deeper.

When police raid bikie gangs looking for drugs they do not always find them, but they usually find firearms.

Such as in the raid on a Nomads clubhouse in suburban Thomastown in 2004 when a policeman accidentally kicked a step, which fell apart to reveal five handguns.

Another raid, in country Victoria, uncovered a cannon, two machine-guns and night-vision goggles at a bikie house.

From their beginnings in the US after World War II, the ‘one percenter’ outlaw gangs fostered an image of hard-living ‘cowboys’ riding steel horses across a mythical frontier, guns on hips.

A lot of rebel gang members were ex-military people who knew too much about guns to live without them. Next step was to trade in them, and so gunrunning has also always been a bikie cash cow.

Australian Hell’s Angels brought back the original recipe for amphetamines from the US in the 1970s and bikies have controlled a slice of the Australian ‘speed’ since.

But guns, the other side of their business, still have to be imported.

According to underworld sources and former police, the most common smuggling method is to hide pistols in engine blocks and mechanical parts imported from the US.

‘Bikies are constantly involved with cars and trucks. They loved bringing in big cars like Cadillacs to restore and drive around,’ says a former drug squad policeman.

‘They would fill the sump with stripped-down pistols.’ Sniffer dogs don’t find guns covered in oil. And, hidden in engine blocks, they are undetected by X-rays. The only way to find them would be to intercept and strip every engine passing through every port.

Barely one in twenty shipping containers is searched, so that’s unlikely.

Even if systematic searches were done at big ports such as Melbourne and Sydney, officials might not be as efficient at some smaller ports around Australia. Such as in Tasmania. Not just Hobart but sleepy Burnie and Devonport.

Underworld lore has it that most new black market pistols arrive in Melbourne from the south, across Bass Strait.

If ‘the Territory’ is the Deep North, Tasmania is the Deep South. Before the Port Arthur massacre in 1996, Tasmania was one of four states and territories with much laxer gun laws – and enforcement – than in more heavily populated Victoria and NSW.

A sparse population scattered over a large area of wilderness, a tradition of hunting and fishing and a rural-based economy meant it had more in common with outback Queensland or the Northern Territory than with Victoria.

Gun use there reflected that – at all levels of society. In a place where many people are related or connected, gun enthusiasts include police, and prison and Customs officers as well as farmers, fishermen and forestry workers, some of whom resented the post-Port Arthur laws that demanded they hand in certain weapons.

Not all did, hiding guns and creating a cache of ‘orphan’ (unregistered) guns that became part of a black market linking some former mainstream shooters with underworld elements.

Enter the bikies. Tasmania offers cheap land in isolated areas, yet is only a short plane trip or boat ride from Melbourne.

Inevitably bikie gangs such as the Coffin Cheaters and the Black Uhlans saw it as a good place to do things away from prying eyes.

Rural solitude is ideal for producing amphetamines and dealing in cannabis and guns. With the state’s small population, low employment and depressed wages, the bikies and their associates exert influence with both muscle and money.

It is widely known in underworld and police circles that large groups of bikies ride the Spirit of Tasmania back and forth regularly, and not to take the fresh air.

Vehicles and luggage are not routinely searched and, in any case, the bikies are skilled hands at building caches for drugs and guns into vehicles.

In theory, guns should be no easier to import to Tasmania’s ports than those on the mainland. Anecdotally, they are. One reason is that until the 2001 terrorist attacks, US Navy ships regularly called into Hobart (and Fremantle) en route to the Middle East.

Authorities either deny or ignore it for diplomatic reasons, but it is a fact that US sailors routinely smuggled in large numbers of handguns, easily done because the sailors do not have to clear Customs.

There is proof this also happened in Melbourne, and every reason to think it still happens in any port where US warships call for rest and recreation.

On November 12, 1998, for instance, the huge aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln anchored in the Derwent River and most of its 5500 sailors came ashore over five days.

One group carried a wooden crate through the rudimentary ‘beach guard’ on Princes Wharf, hailed a taxi and went to a nightclub for a pre-arranged meeting.

Inside the crate were 40 new Colt .45 calibre semi-automatic pistols, a favourite US military sidearm. Not only lethal handguns, these were prized collectors’ items commanding a premium that made the crate of 40 worth more than $100, 000 on the black market.

Today, they would be worth up to three times as much, an indication of how the black market has been inflated by drug money, and the alarming penchant of nightclub poseurs to carry ‘a piece’.

Although smuggling guns is an easy way for American sailors (and soldiers) to raise local currency, the aircraft carrier crew was not after money this time.

As part of a pre-arranged plan, it swapped the crate of pistols for another crate.

This held a breeding pair of young Tasmanian devils, trapped to order a few days before near Richmond, east of Hobart.

Americans are fascinated by the animals because of the popularity of the Warner Bros cartoon character Taz. The devils were smuggled on board the ship.

And the pistols? Almost all of them were taken to the mainland and sold covertly, not all to active criminals.

A former policeman, posted to the Melbourne docks to protect US ships from anti-nuclear protesters in the mid-1980s, recalls several of his colleagues swapping their police jackets for new pistols taken from the ship’s armoury.

‘The first time I went was for the USS Sterett. For some reason the crew were mad on collecting jackets everywhere they went. Obviously the armoury officer had done a deal with the sailors, because they would take your jacket, then direct you to the armoury guy and he would give you the pistol,’ the former policeman said.

‘The funny thing was that every time a (US) warship came into port after that, cops would be running around collecting jackets to swap for pistols.

‘They must have got dozens. From memory they were nine-millimetre Berettas.’

US Navy ships have visited Australian ports only rarely since September 11, 2001.

But plenty of cruise ships and freighters visit, and dozens of them visit Tasmania’s ports. Somehow, somewhere, illegal handguns are flowing in unchecked, according to underworld and police sources.

In Melbourne’s northern suburbs, underground dealers have boxes full of American-made handguns: Colts, Rugers and Smith & Wessons, in calibres from .22 to .45.

Most sell for about $5000 each, but $20, 000 will get five, allowing a cashed-up buyer to sell four to others and keep one ‘for nothing’. Those willing to take the risk can drive them to Sydney, where they bring up to $8000 each.

Handguns have become a fashion accessory for even low level drug dealers who want the gangster lifestyle centred on money, sex and violence.

The most favoured pistols are the most concealable: like the lives of most of those who buy them, they are nasty, brutish and short.

And every one that ends up on the streets, under a car seat or stuck down the back of someone’s jeans is only a heartbeat away from repeating the horror of what happened in Melbourne in June 2007.