My mother, Bettye Jean Triplett née Gardner.

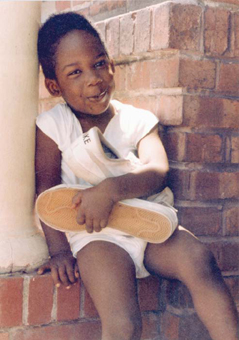

Me as a baby.

Graduation day, me in the center with my navy class, Company 208.

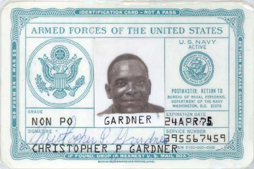

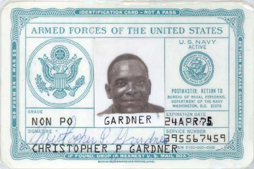

My military ID, an eighteen year old eager to ship off to exotic lands.

My son and I enjoying free outdoor entertainment.

Chris Jr. sleeping.

The quiet before the storm.

Chris Jr. preparing to walk in his father’s shoes.

Chris Jr. finally in a new home after a year on the street.

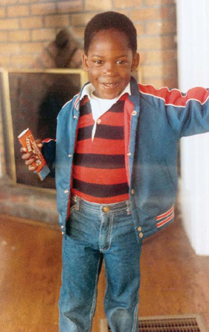

Christmas in San Francisco—Jimminy Cricket.

Shaking hands with President Clinton at the National Teacher of the Year Award ceremony in the Rose Garden.

Uncle Henry, the first man I fell in love with.

Barbara Scott Preiskel:

My mentor, my hero, my patron saint.

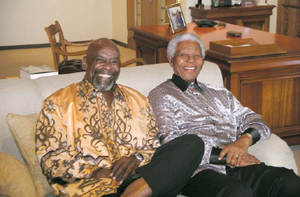

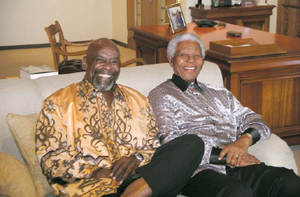

Shoulder to shoulder with the great Nelson Mandela.

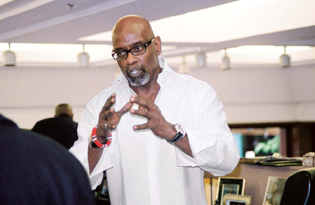

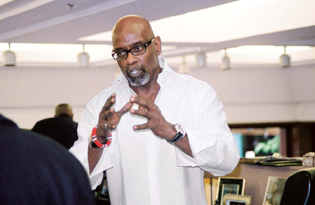

At the helm of my own firm. (Photo by Leonard Simpson)

My head is in my business, but my heart is always with my children.

“That’s what the lecture’s about?” I asked, reminding him that my work schedule was pretty tight.

“That’s the problem,” he went on. “Wanting material things, wanting to be middle-class, aspiring to be bourgeois. You think that your work is who you are, right? No, man, who you are is who you are, not what you do.”

Sounded interesting enough to get me there. Even then, at what turned out to be a seminar called EST, run by a guy named Werner Erhard, nobody would explain what IT was all about. In fact, you had to get IT. And if you couldn’t get IT, you had to be trained to get IT. And you had to pay a lot of money to be trained to get IT. Sitting on the floor, cross-legged, in a room full of nearly a hundred people, my three friends and I kept exchanging frustrated expressions as Werner Erhard and his lieutenants took turns yelling at us, just like in the military, and telling us how our lives weren’t working and how we had all this baggage that we wouldn’t take responsibility for. How could we do that? We had to get IT. But nobody could tell us what IT was! What was more, they didn’t want us to basically leave until we got IT. No eating or going to the bathroom. With my three friends, Bill included, I soon began to roll my eyes in frustration. What I wanted to say was, Look, just tell us what IT is, because maybe we could get IT if we knew what IT was. Maybe we got IT already.

It occurred to me, that not even the seminar leaders seemed to knew what IT was. When that became apparent, after about an hour of all this berating, I stood up and finally said, “Yeah, I got IT.” Just before the EST army could move in, I added, “Fuck IT. Fuck IT, and fuck you, and fuck that.”

The four of us became very vocal. “Yeah, fuck IT!” repeated one of the guys. “IT ain’t shit!” shouted another. Bill yelled, “I don’t want IT!” I finished up by saying, “Keep IT.”

As the only brothers in the room, we started to sense there was going to be a racial issue, but pretty soon most of the white people in the room began to give us looks like, Ah, they do have IT. All hell just about broke loose when one white guy stood up and joined us, saying, “Yeah, that’s right! Fuck IT!” This was enough for us to be escorted quickly out because we had definitely messed up the game. That little experiment proved to me that I didn’t need other doctrines to enlighten me. But Bill kept on searching.

A few years later I heard that he and his lady became followers of a charismatic leader who convinced his flock to turn over all their worldly possessions—to him—and leave the United States for Jonestown, Guyana. In November 1978, I would hear the news that Jim Jones had persuaded over nine hundred followers to drink cyanide-laced Kool-Aid in a mass suicide. Bill was among those who died that day. It really made me wonder how someone who was so street-smart and who could challenge the belief system of the status quo could then adopt such a radical belief system like the Jonestown thing without questioning it.

Part of my defense mechanism was the need I had for control that had been with me since childhood. This was also why I continued to resist the excesses of drugs and alcohol in these experimental years. Of course I tried stuff now and then, like the one time I smoked some angel dust and had to talk myself out of believing that I could fly. The moment the PCP reached my brain, I proceeded to do one hundred pull-ups on the heating pipe in my building—a supernatural feat when I stopped to think that in the Navy I could only do twenty-five pull-ups on a good day.

When I started looking out my window and trying to decide what landmark I should fly toward, something sober and wise inside me recommended: Forget flying, how about a walk?

From the Tenderloin, I walked and walked and walked, effortlessly, feeling that I was rising up with the angle of the hills, then coasting down them, being pulled toward one bridge and then toward another. Magically, I arrived in Chinatown, like I’d been sailing and had come ashore, coincidentally in the middle of a holiday marked by a lavish parade. Without being invited, I joined right in, dancing in the street with everyone in costumes and masks, many holding Chinese lanterns and papier-mâché creatures, many looking at me strangely, no doubt wondering, Who is that happy man? He’s not Chinese.

By the time I started to come down, I was in a bar in North Beach, grooving to an eclectic band that comprised a snare drum and a harmonica. Man, I thought I had to be in Carnegie Hall. It was a good thing that I recognized how dangerous that high was. Music in itself can be a mind-altering experience, so to be on an even more altered level, the music was just mind-blowing. Out of control! When it came time to finally return to the Tenderloin, I trudged home not so effortlessly, sobering up fast and realizing that this wasn’t a drug I needed to try again.

The reality was that for all my exploration during off hours, my major focus of experimentation was in the laboratory doing the work that Dr. Ellis had brought me out to do for him. My friend Bill who took me to the EST meeting had accused me of having bourgeois aspirations, and it was true—I was seduced by the idea of a potential career in medicine. If that was what I wanted, if I was passionate and dedicated, Bob Ellis was willing to place an incredible amount of trust in me, to teach me, and to open up an entirely new world in medical research, one that was different from the Navy world I’d worked in.

The project was being conducted in conjunction with the Veterans’ Administration Hospital—located at the farthest beachhead of San Francisco at Fort Mylie, out by the Golden Gate Bridge—and the University of California San Francisco Hospital, near Golden Gate Park and Keysar Stadium. At the VA, where I spent most of my hours, the research aim was to create a laboratory—basically from an old operating room—that duplicated the environment in which the heart functions during open-heart surgery. Specifically, we were trying to determine what concentration of potassium best preserved the high-energy phosphates in the heart muscles. We would do a set of experiments with a high-potassium solution, a set with a low-potassium solution, and a set with a minimal-potassium solution, taking samples of heart tissue over time and using those results for our findings. Ultimately, it was the high-potassium solution that we found to be most conducive to preserving the high-energy phosphates—information that would transform how heart transplantation and surgery were done, as well as influence cardiovascular science. For an information sponge like me, this work put me right in my element.

“Gardner,” said Dr. Ellis on one of my first days of work, “I want you to meet Rip Jackson.”

I turned to take in the startling appearance of Rayburn “Rip” Jackson, imported to San Francisco by Ellis from back in Jacksonville, North Carolina. Just as Dr. Ellis looked the part of a young brilliant surgeon—average height and build, glasses, balding, with a nose like an eagle’s beak, meticulously sniffing out details, passionate, and sometimes high-strung—Rip Jackson had the mega-wattage intensity of the medical scientist-technician genius that he was. Slim, short, and clean-shaven, with shocking white hair and small, piercing blue eyes, Rip extended his hand to shake mine and greeted me in an accent that was purebred country boy, straight out of the North Carolina backwoods. “Nice to meet ya’,” he said, with barely a smile. “Heard a lot about ya’, Gardner.”

My instincts told me that Rip could have been a Ku Klux Klansman in his younger days. Something about him reminded me of that old woman at the gas station who threatened us with a shotgun. He wasn’t so extreme, but as time went on certain comments he let slip confirmed that he was a bigot all right. Having worked for many Jewish doctors, he apparently was careful not to make anti-Semitic remarks. But perhaps because he’d had little exposure to black doctors, Rip didn’t censor himself, for example, when it came to expressing how he felt about seeing an interracial couple at the hospital. He shook his head in disgust, commenting to me, “I think I’d rather see two men together than a black man and a white woman.”

Interestingly enough, it may have been a function of how well we got along that he made comments like that in my presence. In any event, from the beginning he saw not only that I wanted to learn from him but that I was quick to get IT, and he treated me with the utmost respect. The way we progressed was that he came out initially for a month, trained me to oversee everything that Dr. Ellis needed done for the next six months, and then came back at various intervals as needed.

His personal racist hang-ups aside, Rip Jackson was so great at the mechanics of building a laboratory and teaching me how to run it that he earned the utmost respect from me. Even though he wasn’t a licensed medical doctor, his technical expertise equaled that of a top surgeon, and he trained me in this highly specialized area to do everything to support Dr. Ellis. Our responsibilities ranged from excision of hearts to catheterizing blood vessels and suturing, from ordering equipment and supplies to administering anesthesia, performing biopsies on heart tissues of patients, and analyzing the results.

Adding to the extraordinary education I was getting from Bob Ellis and Rip Jackson was a third exceptional rocket scientist in the medical laboratory—a guy by the name of Gary Campagna. Gary didn’t have a medical degree either, but did for a vascular surgeon named Dr. Jerry Goldstein what Rip did for Dr. Ellis. A San Francisco native, Gary was witty and hip, an Italian American gentleman, and he took me under his wing, teaching me about technique and the importance of finesse. I now saw that it wasn’t enough to know what you were doing; you had to have the hands, you had to have the right touch.

Gary had memorable sayings to emphasize certain techniques. In grafting veins, for example, precision was mandatory in first being able to control the blood flow—to shut it off, basically, like a spigot—in order to excise the portion where the graft needed to go, then to suture it all the way around without any blockages. In the clinical setting, I learned how to do that, to determine the kind of slice required for excising a portion of the artery, what type of sutures to use, what type of ties to make, what kind of graft ultimately would be needed depending on the condition of the vein. Gary warned me off making the common mistake of trying to handle the vein too abruptly, cautioning, “Stroke it, don’t poke it.”

These three—Gary, Rip, and Bob Ellis—were providing me with the equivalent of a medical school education, at least in this specialty. As the game plan now unfolded in my mind, I imagined that once our work was completed and I took the time to knock off a college education, I would be a prime candidate for any top Ivy League medical school in the nation. The prospect was thrilling. Could I really do that? Could I reach that far? My mother’s words echoed—If you want to, you can.

The excitement didn’t come just from the potential status and money that a career as a surgeon promised. To me, it was the challenge, the quest for information, the opportunity to apply my focus in a venue that required me to learn what amounted to a foreign language. It was starting to dawn on me that there was a language specific to all things and that the ability to learn another language in one arena—whether it was music, medicine, or finance—could be utilized to accelerate learning in other arenas too. Scientific language was fun to master—not only the medical words and meanings but also the prose, with its rhythm of urgency and its precise way of describing phenomena and processes. That understanding of process—how to get from here to there—was the real bait for me, what hooked me and made me want to learn more. Because I was so motivated and naturally curious, the learning felt easy.

Once I had learned the language, doors at the VA and the UCSF Hospital literally opened as Dr. Ellis brought me in to sit and talk with the top tier of his medical colleagues. In those settings few had any notion that I hadn’t been to medical school and wasn’t a doctor, let alone that I had never been to college and had barely finished high school. Sure, there were moments when I felt my lack of education, but I discovered that rather than pretending to know something I didn’t, there was a way to ask, “Now, I’m not following you here, can you explain?” that most doctors were more than happy to answer.

In time, Bob Ellis developed so much faith in my mastery of our research that I went on to co-author several papers with him on the preservation of myocardial high-energy phosphates—papers that were published in various medical journals and textbooks. Even some Harvard Medical School grads can’t claim to being as widely published.

“Where did you go to med school?” was a question that inevitably came up, especially from the interns working under Dr. Ellis and Dr. Goldstein. It confounded Ellis that so many of the interns who were starting their residencies in surgery had so little practical awareness. They didn’t have the hands, didn’t have the eyes, didn’t know the controls or the procedures. Some didn’t know how to handle instruments. Instead of wasting his time on these basics, he started sending them upstairs for me to train. Suddenly, all those questions that I had been asking—“What are you doing?” “How do you do that?” “Why are you doing that?” “Can I try that?”—became questions that I was answering.

The interns were all bright and knew anatomy and physiology, biology and chemistry. But only a few had the hands. I frequently caught myself sounding just as intense as Dr. Ellis, Rip, and Gary combined. During tests that involved open-heart surgery on dogs, it was maddening to witness rough handling, as often was the case, of the canine patient’s arteries and fragile organs. In my lab, as Dr. Ellis called it, I was free to say, “No, don’t pull. You apply pressure gradually.”

When an intern gave me that look that said, Who are you to tell me what to do? I was even more adamant, raising my voice and saying again, “No, you don’t do it that way. You’re not up under the hood of your car.”

There may have been some bigotry involved, given the fact that the interns at the time were all white males from Ivy League medical schools and I was some black dude without a medical degree saying, “No! I don’t want that. Give me the scissors!” But what really seemed to get on their last nerve was that they had to do what I said. Dr. Ellis made it clear to every intern he brought upstairs to me: “This is Gardner’s world. Whatever he says goes. He’s in charge.”

My feeling was that if someone wanted to learn or was willing to try, I’d bend over backward to help. But some of the interns were so arrogant, they dismissed my input out of hand, as indicated less by what they said and more by their body language, which showed they didn’t want to listen to me. In those situations, all I had to do was to tell Dr. Ellis, “You know what? This guy Steve—I can’t help him.” That was it. After that I’d never see the intern again. On occasion I was even more specific: “That guy Richard—he doesn’t want to listen. You know what, don’t waste my time, don’t send him back to my lab.” Dr. Ellis only nodded in agreement, respecting my opinion and appreciating that I was as passionate as he was.

Dr. Goldstein’s interns in vascular surgery were some of my tougher challenges, giving me big-time attitude when I called their lack of finesse into question, reminding them of Gary Campagna’s “stroke it, don’t poke it.”

“What exactly are your qualifications?” some of these interns were indignant enough to ask out loud.

My matter-of-fact response was: “I don’t have a degree, but this is my room. You’ve been invited here. You’re a visitor, and I’m doing my work. If I can help you, I will, but you have to listen.”

In certain instances, I could see by the expressions of resentment on some of their faces that they had never had any black person in authority telling them what to do—they had never encountered a black person in control. Some were able to get past that hurdle; some weren’t. For my part, I had to learn not to take some of their superior attitudes personally, in the same way that I couldn’t take it personally when my mentors put me in that position of control. The powerful truth that emerged for me was something Moms had tried to tell me when I was younger—no one else can take away your legitimacy or give you your legitimacy if you don’t claim it for yourself.

Before leaving for the Navy, I had apologized to her that I hadn’t gone on to college, thinking how proud that would have made her. Momma surprised me by saying, “Boy, it’s better to have a degree from God than from anywhere in this university system. If you got your degree from God, you don’t need all this other stuff.”

In my mother’s language that didn’t mean that an intricate knowledge of the Bible or religion was required. Rather, she was talking about self-knowledge, about an authentic belief system, an inner sense of oneself that can never be rocked. Others may question your credentials, your papers, your degrees. Others may look for all kinds of ways to diminish your worth. But what is inside you no one can take from you or tarnish. This is your worth, who you really are, your degree that can go with you wherever you go, that you bring with you the moment you come into a room, that can’t be manipulated or shaken. Without that sense of self, no amount of paper, no pedigree, and no credentials can make you legit. No matter what, you have to feel legit inside first.

Momma’s point of view certainly resonated during this period, not only when I was being questioned but when I questioned myself. There were times during meetings of more than one hundred doctors—some of the brightest minds in medicine—when I’d look around and notice that I was the only black man in the room. But if it wasn’t an issue for me, it didn’t have to be an issue for others. My blackness was a fact of who I was, yet the more comfortable and secure I became in my expertise, the less my color defined or distinguished me, and the more comfortable I became holding my own with white people further up the ladder than me or lower down. What distinguished me was my knowledge, my command of the information that was the focus of the research Robert Ellis was pursuing. This awareness gave me incredible confidence that I could succeed in this field of endeavor, and succeeding meant the world to me. That was why I was prepared to hang in for the long haul, even if it took me another fifteen years to attain the degrees necessary for me to practice medicine. Whatever it took, I was worth it, as was the effort to study and learn, day in and day out, repeating tests sometimes over and over again, like a blacksmith hitting an anvil every day.

There were only two clouds on the horizon—money and sex. Even though Dr. Ellis kept increasing my salary, up to around $13,000 a year by early ’76, there was very little more he could squeeze out of his overall budget for the project. Even for someone who was willing to slum it, San Francisco was a costly place to live. Believe me, living in the Tenderloin—in the same neighborhood as the Y but in an apartment of my own at 381 Turk Street—I was definitely slumming it. My salary was stretched even without car payments or insurance. Since I couldn’t afford a car, I hadn’t even gone out to get my license yet, although I did know how to drive and sometimes ran errands for work in the hospital van. The necessity of getting a second job loomed. Then again, that would use up whatever free time I had for enjoying something of a social life.

The constant money crunch I could handle. But the sudden halt to my heretofore successful pursuit of the opposite sex was a shock to my system. What was going on? In a city like San Francisco, full of beautiful single women, I couldn’t for the life of me figure out why nothing was clicking. Not that I wanted to fall in love, but what I really wanted, to get laid, wasn’t looking good. There was a doctor I’d started seeing, one of the few African American women I’d met at the hospital. She was attractive in a smart, ambitious way, but she was uptight about sex. The chemistry never happened.

Then there was a pretty sister that everybody at the hospital was into. Sweet and curvaceous, with long wooly hair and a rich caramel complexion, she finally accepted my invitation to go to the movies, and we started hanging out. Seemed like it took forever to get an invitation back to her place, but when it happened at last, in a cruel twist of fate I was so tired from work that day I actually lay down on the bed to get comfortable with her and promptly fell asleep.

The next thing I knew this lovely woman scorned was shaking me by the shoulder and pointing to the door. Glumly, I scuffed on out of there, apologizing all the way. As I stepped outside a gust of wet wind smacked me in disdain. “Sure is cold out here,” I said, hoping she’d change her mind.

“That’s too bad,” she replied, “because it’s hot in here.” Then she slammed the door in my face.

That was the sad state of my extracurricular life on that memorably beautiful spring day when I was out on my own at Union Square and the middle-aged guy with the briefcase struck up a conversation with me about San Francisco being the Paris of the Pacific.

As it’s getting toward late afternoon, there is nothing out of the ordinary when he says, “Hey, I’m going around the corner to have a drink. Care to join me?”

Even though I don’t drink much, I figure—Why not? I’m still getting to know the city and not sure where the women are hanging, so I tag along enthusiastically. The bar, a joint called Sutter’s Mill, turns out not to be where the women are hanging. In fact, as we step inside the pitch-black interior of the place and I try to focus my eyes in the darkness, I don’t see any women. What I do see are nothing but men, and two of them are in a corner kissing. Of course, I realize that this is a gay bar.

“You know what,” I say to the guy, as if I just looked at my watch for the first time, “I got an early shift tomorrow, and, uh, great to meet you, but I gotta go.”

Before he can say a word, I’m gone.

This isn’t the first time I’ve been hit on by gay men in San Francisco. Usually, I have no problem explaining that I don’t work that side of the street. Actually, compared to the attitudes in the Navy, I think of myself as extremely tolerant. Yet with my bad case of the no-woman blues, I’m not even in the mood to be polite.

Unable to establish a relationship here in San Francisco, I find myself picking up the phone more than usual to call my long-distance girlfriend, Sherry Dyson, who I have never quite gotten over since that first time I saw her with the T-shirt in the window of the army-navy surplus store. In this time period, she has returned to Virginia with her master’s degree and is working as an educational expert in mathematics. Besides our regular phone contact, she has been out to visit a couple of times, although neither of us has made any moves to indicate that we should be getting more serious.

So we’re talking one night and it hits me that there’s no one who gets me like Sherry, no one who can just say, “Chris, you’re full of shit,” when I’m being too full of myself, and no one else that I’ve ever pictured with me in the life that I’m working toward. In a romantic rush, out of the blue, almost just to hear myself say the words, I change whatever subject we’re on and ask, “All right, so when we gonna get married?”

Without skipping a beat, Sherry says, “Well, how about June 18?”

So much for sexual exploration and experimentation. Not sure what I had just gone and done, I said good-bye to the no-woman blues and prepared myself to enter into the institution of marriage.

For the next three years I lived what could have been called in some respects a storybook life. The wedding, held as planned on June 18, 1977, was picture-postcard perfect: beautiful, tasteful, and simply done in a park near Sherry’s parents’ home—a place that had become synonymous in my mind with stability and security.

Moms was there, glowing with pride. She and Sherry bonded immediately. My Navy buddy Leon Webb, soon to head out to San Francisco, flew in to be my best man, and he couldn’t have been happier for me. We were all impressed with the Dysons’ home. Nothing over the top, the house looked like something out of a magazine—exquisitely decorated with southern charm, rare artwork on the walls, chandeliers throughout the two-story space, gourmet food in abundance, and a bar stocked with wine and liquor imported from around the world.

The Dysons’ way of life represented the ideal of home that had been in my dreams from the time I’d seen The Wizard of Oz as a kid. For a while, I’d even dreamed of moving to Kansas when I grew up because of that portrayal of safety and serenity. In Oz there were witches and maniacal flying monkeys and the same sense of imminent insanity that was in our household. Back in Kansas, folks were normal and kind, and there was no threat of not knowing what could happen next, how far it was to the pay phone, would the police come in time, would your mother and siblings be killed when you got back.

Part of the attraction, unquestionably, was my longing to belong to the world that Sherry came from—a world in which she had grown up adored as an only child, with the same mother and father together, the same house, with a sense of being anchored and with none of the chaos and violence that had afflicted my childhood. Her parents didn’t seem to mind that I came from a different world and were as gracious as they could be in welcoming me to their family. Certainly, like Sherry, they saw that I had potential and was on a solid path to becoming a physician, even though I had a ways to go.

Still, I had begun to have misgivings about this marriage from the moment I spontaneously popped the question, much of which I passed off as typical prewedding jitters.

The first person I had told in San Francisco was Dr. Ellis. If I was looking for someone to beg me to reconsider, Robert Ellis wasn’t that person. Genuinely pleased for me, he went on to loan me the hundred bucks I needed for a suit to get married in, and then he shocked me even more by suggesting, “Take an extra day off.” For a guy who was as obsessed with work as Buffalo Bob, that was unheard of.

My next stop was the jewelry district on Market Street, where I miraculously found a diamond ring for nine hundred dollars that I bought on credit. It looked old-fashioned, with clusters of little diamonds in a flower shape and a band that turned out to be white gold. En route to Virginia on the airplane, I was so nervous carrying a diamond ring in my pocket that I had to check on it every five minutes to make sure it hadn’t been mysteriously stolen during that time. It was the nicest thing I’d ever bought for anyone, and I was sure Sherry was going to like it.

My misgivings vanished the moment the two of us embraced upon my arrival. We had a deep connection, a comfort and fondness for each other that was really all that mattered. Watching Sherry take charge of the wedding made me admire her even more. She had planned everything, her Pops had written the check, and all I had to do was show up. I loved how she carried herself, her confidence, intelligence, and humor, her vivacious manner that attracted people to her in general. She was gorgeous in a wholesome, distinctive way, and her legs were great. I loved her strong personality and the fact that she had definite opinions about what she liked and didn’t like. Therefore, it didn’t bother me that she wasn’t so crazy about the ring.

“Oh, it’s beautiful,” she reassured me. “Just not the cut I had in mind.”

I had no idea what that even meant, but I wanted her to have what she wanted, so we agreed to exchange it when we went back to San Francisco. For all I knew, they might have been cubic zirconium, not even diamonds. That was something else I appreciated about Sherry, that she could educate me about the finer things in life. Caught up in the festivities, we both were in one major whirlwind, and it was only the next morning, after a farewell brunch, that the two of us had a chance to be alone as newlyweds. Neither of us said as much, but the reality had finally settled in. We were both probably wondering if we really had done the right thing.

Nonetheless, with our lives together ahead of us, we packed all of Sherry’s earthly belongings into her blue Datsun B210 and hit the long road to San Francisco. Even though my mother-in-law had insisted that I get my driver’s license while I was in Richmond, Sherry did most of the driving. In spite of the summer heat that hovered from start to finish across Interstate 80, the lack of air conditioning in the Datsun, and my frequent naps, we had enough to talk about and plan to make the trip at least a little less arduous.

Sherry had visited me before in the Tenderloin and was somewhat prepared for the seedy atmosphere that greeted us, although she was adamant that we move from 381 Turk as soon as possible. In no time, she got a job as an insurance claims adjuster, and shortly after that she greeted me with the breathless news, “I found a place on Hayes. I fell in love with it. It’s a third-floor walk-up with hard-wood floors, bay windows, and French doors!”

This was all foreign to me, but if it made Sherry happy, I was happy. Still in the ’hood, the area was known as Hayes Valley and had a lively black community feeling to it, not to mention that we were out of the ’Loin. Thus, we entered into a nesting phase as Sherry turned our new apartment into a warm, welcoming environment. She decorated amazingly on our budget—with potted plants like ficus Benjamins and wandering Jews adorning shelves and hanging from the ceiling, a nice brass bed, a wicker rocking chair, a stylish couch, new cookware and serving pieces. I was as into transforming our living space into a home together as she was.

In the kitchen, Sherry was a fantasy come true. Man, could she cook: soul food including the best fried chicken ever, pasta in every shape and form, and gourmet dishes to rival any of the great chefs of San Francisco. She was always coming out with new creations too. “Remember the way they made that dish at the Vietnamese restaurant?” she’d say. “I’m going to try doing something like that.” And it would be even better.

We moved up in the world again after Sherry met me at the door one night and announced, “Wait until you see the place I found on Baker. It’s in one of those Victorian buildings I’ve had my eye on. Chris, you’ll love it! It’s got five rooms, great sunlight.”

I only laughed and went along with the plan, thinking not only how much she enjoyed re-creating for us in San Francisco what she’d grown up with in Virginia, but also how lucky I was that she was educating me, elevating my sense of culture and style. She wasn’t just giving me an awareness of what a Victorian-style building was, something I never knew, she was opening me up to a lifestyle that included theater, comedy, and social gatherings with fascinating, intellectual conversation. We filled my few nights off with trips to comedy clubs to see the likes of Richard Pryor or to dinner parties with a serious, creative crowd at the home of Sherry’s cousin, Robert Alexander, a writer. Whenever we were there, I gravitated to the same group of three guys, very smart, hip, and active in the arts. One was a brother named Barry “Shabaka” Henley, and the other two were cats named Danny Glover and Samuel L. Jackson. Little did I know the three would later be in the top tier of actors on stage and screen.

But even while our portrait of a happily married life seemed to be what we both wanted, within a couple of years I began to confront a feeling deep down that something was missing. If I had been better at communicating my feelings or if I had taken the time to try to resolve what wasn’t working, it would have been so much better than what I did by trying to ignore and run away from the problems.

Some of those problems had to do with basic differences in where we came from and in our likes and dislikes. Sherry liked the better restaurants on Fisherman’s Wharf; I liked the countercultural vibe of the Haight. To me, the better restaurants were predictable; to Sherry, the anything-goes, hippie atmosphere of the Haight was too wild. Fairly conservative, she was a good churchgoing Episcopalian. That mentality was nothing like where I’d come from: straight-up Baptist, and that’s all I knew. Episcopalians reminded me of Catholics in church, always doing calisthenics on cue—standing up, kneeling down, standing up again, kneeling back down again, reciting lines appropriately, in unison. Quiet, dignified, subdued. Being demonstrative with feelings seemed to be discouraged. Tears were dabbed away by handkerchiefs or simply held in. Not like in the Baptist church, where there was competitive shouting. No comparison. In the Baptist church where I grew up, when my big sister and I were taken there by Aunt TT, folks sang, danced, sobbed out loud, spoke in tongues, had dialogues with the preacher and God at the same time, and caught the Spirit in the most dramatic ways. Women threw up their arms, screamed, and fainted! Men jumped and shouted! Every Sunday somebody got carried out. As a kid, I didn’t know intellectually what was going on, but it was exciting and real. Oh, man, it was hot too. Episcopalian churches were cool, hardly a drop of sweat to be seen. In the church where I grew up, you got high on the heat. Those fans everyone had didn’t do a damn thing to cool us off.

Of course, I enjoyed going to church with Sherry, knowing it would open me up to new things. But there was a loudness, a wildness that was lacking. In my heart of hearts, I was slowly coming to face the truth that I didn’t want to live a picture of a life—whether it was by having to live up to the role of doctor that I was striving for, or whether it was in my marriage. Sherry had to have been having similar concerns, especially when a parade of houseguests started descending on us.

When my best friend Leon Webb came out to get work in radiology, the path he’d begun in the Navy, that wasn’t a problem, even though he stayed for three or four months. Sherry and Leon got along just fine. But when my childhood buddy Garvin came to stay for a while, she and he didn’t mesh at all. This was her home, after all, so I was in the position of encouraging Garvin to find somewhere else to stay, soon, which unfortunately hurt our friendship. Of course, if things had been just peachy with Sherry in other respects, it wouldn’t have been an issue at all.

The real problem that took me forever to admit had to do with what was or wasn’t happening in the bedroom. We loved each other deeply, profoundly. We were presidents of each other’s fan clubs, cheering each other on more than anyone else. But our sex life was nice, predictable, quiet. Not hot. I wanted to compensate for not getting to go around the world and meet all those foreign, exotic women. I’d had a taste or two of the X-rated versions, and I wanted more, what else could I say? But rather than say something or initiate what I wanted, I became aloof.

We might have been hamstrung from the start. After all, we had built our romantic relationship over telephone wires and on letter paper, always with that theme music of Summer of’ 42 playing in the background. Early on, it had been a major turn-on to be the younger man with the more worldly, college-educated woman. Now I was looking to her to introduce more spice. But she didn’t know that, and I didn’t know how to shake up the routine.

Ironically, the safe, stable home that I’d wanted since childhood turned out to be too structured, too orderly, too rigid. Later I was able to take the long view and realize that I had gone from one institution, the Navy, to another, marriage, with barely a break in between. At the time, I didn’t stop to think about it in those terms, except to realize perhaps that I’d learned the classic lesson: Be careful what you wish for because you might just get it!

Obviously, I had some serious inner conflicts about what really was the good life for me. Those qualms were put to the side when Sherry became pregnant, something that was as exciting and different as it was terrifying. Instead of questioning my marriage, I put those doubts on the back burner and suddenly began to question, for the first time, how married I was to the idea of becoming a doctor. Even though I was up at sixteen thousand dollars per year now, that wasn’t going to support a family and pay for me to go to college and then med school. I went out and got a second job.

Not out of her first trimester, Sherry miscarried, a disappointment to both of us, but one we took in stride. Now that I’d faced the need for more money, I kept up my second job working as a security guard at nights and on weekends, not doing too badly. That was, until I was sent to fill in on a graveyard shift at the pier as the guard of a creaky old unused ship. With nothing but a flashlight, I took up my post at a chair, freaked out by the horror movie sounds but too exhausted to stay awake, only to be nudged back into consciousness by something rubbing up against my leg. My first thought was of those cats in my nightmares about the witch woman’s house back in Milwaukee. Instead, when I felt that same thing scratch me, I looked down and saw a rat the size of a large cat, its jaw unhinged and preparing to munch on me. As God was my witness, my time in the Navy notwithstanding, I had never been on a boat before and had no idea that there were rats on boats and had never dreamt that rats could be so goddamned huge. Screaming like a girl, I jumped straight up out of my chair. The rat screamed too and ran, and so did I, the two of us in separate directions. So much for my stint in security.

From then on, I managed to grab odd jobs here and there in my off hours, doing things like painting houses on the weekends and working for moving companies.

Though she said nothing, Sherry may have noticed that I was spending less time at home, not just because of these extra jobs, but because I was looking to break up the routine. Some nights I went by myself to hear music on Haight Street; other times I hung out with some characters I’d met in the neighborhood, watching football games, smoking some weed, passing time. Sherry wasn’t overly fond of some of these cats, especially a couple of the guys who had moneymaking enterprises that weren’t all on the up-and-up. In one of my covert acts of rebellion against too much structure, I actually went so far as to try to make extra dough dealing on the side. Besides the fact that I was a complete failure at it, I practically got myself killed when some big-time gangsters came waving guns to collect cash that I didn’t have. Somehow I got hold of that cash real fast. It wasn’t more than three hundred dollars, but to a ghetto boy like me, that hurt. When a couple of my friends next proposed that I go in with them on an insurance scam, I politely declined.

My short-lived life of crime had the fleeting effect of making me grateful for what I had at home and at work. It also taught me the major principle that there ain’t no such thing as easy money. Banging on that anvil, that was the way. Even so, it was frustrating after five years that I hadn’t been able to buy a car. Sherry’s Datsun B210 still was our only means of shared transportation, though fortunately we could both take advantage of San Francisco’s excellent public transit system. There were also morning rides to work that I hitched with my coworker and friend, Latrell Hammond.

“Chris, listen to me,” she’d begin every morning when I jumped into her much-abused, lime green 1961 Ford Falcon after she arrived to pick me up. Every morning she had some new advice she was selling, and it was usually good. A force of nature, Latrell had the gift of gab as one of the fastest-talking, most scandalous women I’d ever seen in my life, with the ability to sell you anything—including your own shoes that you had on your feet at the time.

Latrell and I were strictly platonic friends. She and Sherry were tight, so she had the best interests of my marriage in mind at all times. There were occasions, however, when I’d wonder if she had the best interests of me surviving her driving in mind. Latrell was outrageous. But because of her gift for gab, no matter how late we arrived at work—and she was chronically late—she could always pull it off. From the minute I hopped in the car, as I tried to follow her latest line of conversation, and as the two of us slid around on the Falcon’s seatbelt-less bench seats, Latrell gabbed away, putting on her makeup, drinking coffee, smoking and gunning for the green lights, all at the same time.

She acted completely unaware that I was praying aloud, “Oh, my God, don’t let me die in this lime green Ford Falcon.”

If we caught all the green lights, we could make it to work in fifteen, sixteen minutes. That’s still not good if you’re already late. But if one red light caught us, we were shit out of luck. Remarkably, while I didn’t even bother trying to make excuses when a whole room full of interns were waiting for me to arrive, in her department Latrell had a new and exciting excuse every day—which her superiors never questioned.

Sherry was such a contrast. There was only one morning, to my knowledge, that she left the house without being organized and in control. That was revealed later that evening when she returned from work and confessed that something was wrong.

Was this the conversation that I had been hoping for and dreading at the same time? “What’s wrong?” I asked.

“I think something’s wrong with my ankles.”

“Your ankles?”

“I’ve been walking funny all day,” she explained. “I can’t figure it out.”

Being the investigative medical guy that I was, I suggested, “Let me take a look.” When I did, at first I saw nothing. Then I realized, cracking up as I did, that she had become a fashion victim of what I called her shoe garden. Because she had amassed such a collection, she kept the shoes neatly arranged in a basket in our bedroom. But somehow in her haste to get to work on time, she’d grabbed two different shoes.

She joined in laughing with me when she saw it for herself. That was so unlike her. But it was indicative of how together and consistent her routine normally was.

A short time after that incident, I had a reaction to a Richard Pryor line that was indicative of how much I was dying for a change in our sexual routine. Pryor was talking about some of the crazy things that doing blow could do to people. At the time, I had only tried it once and didn’t get what all the hype was. Now Pryor was talking about how it affected your sex drive, and he was telling a story about how he’d be high and make up wild stuff to do, telling his lady, “Now, baby, I want you to go up on the roof. I’m going to run around the house three times, and on the third time I want you to jump off on my face.”

Sherry didn’t laugh. I didn’t laugh either. Instead, I thought to myself, Aw, yeah, that would be cool.

That’s where my mind was lurking. So when I meet this kind of cute, kind of plump, but fairly hip woman with a short tight natural who happens to have a nice little place and who happens to tell me, “I really want to give you a blow job,” I do not say no. And when I say yes, and this kind of cute chick turns out to be a fellatio expert, I start to mess up bad. Really bad. It’s stupid enough to be stepping out to get my dick sucked, but worse, I invite this woman to where I live when Sherry’s at work one day and I have the afternoon off.

The whole time I’m doing it, I feel so good, but the minute I come sanity returns, and I know that this is one of the worst mistakes I’ve ever made in my life. Not just because it’s wrong every which way, but because in the last few times we’ve gotten together, I’ve come to understand this woman is stone cold crazy. The next time I see her at her place, I let her know that while it’s been swell, we shouldn’t get together anymore.

“What are you trying to tell me?” she asks, fury in her eyes.

“Well, I don’t want to see you anymore.”

“Are you breaking up with me?”

Realizing that she’s not getting it, I try to remind her that we weren’t together that way to be a couple in the first place. “Look,” I say, “you’re the best, and I’ll remember our time together, but nothing else is gonna happen between us. Let’s just be friends.”

Now, either she is not satisfied with how I’ve broken it off or she is really nuts, because a few mornings later I wake up in the morning to find that Sherry’s car, the Datsun B210, has been brutally vandalized. A can of white paint has been dumped on top of the roof, spilling white stripes of paint right down the windows and the windshield wipers, everything. The tires are slashed, sugar’s in the gas tank, and prominently etched by finger in the paint is a message that reads: FUCK YOU!

I know who’s done it but I can’t prove it. I can’t let Sherry know. Standing there pissed off at myself more than anything, I decide that I’ve got to now lie big-time and say that I’ve got no idea who would have done something so violent. A random act, no doubt.

A brother from the neighborhood approaches as if to make conversation. “Hey, man,” he says, “let me holler at you for a second.”

Not wanting any chitchat, I turn away, letting him know, “Yeah, okay, talk to me later.”

With a shrug, he insists, “I was just trying to tell you who did that to your car.”

“Oh?” What else am I going to say?

“It was that little fat bitch with short hair,” he says with a snicker. “Okay?”

Well, I know who did it, the street knows who did it, but thank God Sherry doesn’t know, and the insurance agrees to cover it, only after they ask, “Mr. Gardner, what happened?”

“I don’t know,” I say in my most indignant voice. “I came out and found it like this. I must have made somebody angry, but I don’t know who it was. Maybe whoever did this just made a mistake. I just don’t know.” The insurance claims person points out that a message like that is usually personal, not a random act or a mistake, but leaves it at that.

In the days that followed it was obvious from the whispers and looks that word had traveled through the grapevine. The incident soon passed but remained an ugly memory for me. Sherry never indicated that she knew anything about it, but she did seem to be picking up on my discontent, asking me more often than not where I was going or where I’d been out late the night before.

When we finally did have a talk, toward the end of 1979, with my twenty-sixth birthday not too far down the road, it was to confront a change of professional plans. I had decided that I wasn’t going to be a doctor.

Baffled, Sherry groped for words. “Why? I mean…” She just looked at me. “Isn’t that what you’ve been working toward?”

She knew that the challenge was gone. We had talked about that before. I was already the medical whiz kid. It was going to be ten years more of education before I could officially do what I already was doing. But it wasn’t just that, as I explained to Sherry. My mentor, Dr. Ellis, had raised his concerns with me, opening my eyes to some of the trends that were about to radically alter the health-care field. In plainer language, he had said, “Chris, you really need to reconsider being a doctor because it’s going to become a vastly changed profession.”

What was coming down the pike at the time were versions of socialized or nationalized medicine, precursors to what became HMOs. As Dr. Ellis rightfully predicted, this meant that a top surgeon who might make several thousand dollars per surgery then could be looking at as little as a few hundred dollars for the same services in coming decades. Not only were the new insurance plans going to cover less, but they were also going to emphasize noninvasive procedures and create bureaucracies that set fee structures. Bob Ellis made it clear that he believed in me, that I had the talent and energy to succeed and, even more important, to make a contribution to others.

Except for the time that Moms had told me I couldn’t be Miles Davis, no one else had ever put a hand on my shoulder to steer me in one direction or another. I had to listen. As I went on to explain to Sherry, there were plenty of options for me in the medical field, perhaps in administration, sales, pharmaceuticals, or the insurance business. I would start checking out some of those options as soon as I could.

There was even a sense of relief that flooded me. No longer did I have to play the part of a future doctor. But Sherry was anything but relieved. That future had been part of the package she married: Chris Gardner, college graduate, medical student, doctor. She had every reason to be disappointed, even though she expressed her support for whatever I decided to do.

After cheating on her already, I had made up my mind 100 percent never to repeat that mistake. Yet we were starting to drift further apart, our differences showing up in stark ways.

This comes crashing in on me on a Saturday after we head down to Fisherman’s Wharf, just to do some sightseeing and some shopping, when I can’t help but notice this fine woman out for a stroll. I don’t want to ogle, but my penis stands up at attention to salute, rock hard. Everybody in the vicinity on Fisherman’s Wharf gets a full view of me walking around with a major piece of wood bulging in my pants.

One brother walks by and comments, “Still strong, huh?”

What can I do? Kind of embarrassed, but not really, I glance over at Sherry and am shocked to see how livid she is. “That’s disgusting,” she says, mad as hell.

There’s a part of me that wants to get mad too and tell her it’s not disgusting, it’s normal. There’s another part that’s regretting not having taken the time to be single and sow my wild oats a little more.

It’s funny how life can turn on such an unplanned minor event as a spontaneous boner or a thoughtless comment. In that moment the stage was set for my marriage to be over. I would always love Sherry Dyson to death. What she had given me was so much more than the picture of a life I was looking at, maybe more than any woman, other than Moms. Sherry gave me the gift of believing in me, of pushing me to set the bar high for myself, of sending me the message that I was worth it—sometimes when I had forgotten. Whether she was ready to admit it or not, back before we were married, she too had definitely felt some ambivalence about our long-term prospects, but her love was always unconditional. In years to come, she would become my best friend in the world, even though in the short term she would suffer terrible hurt for which I was sorely to blame.

The real turning point that changes everything in our marriage and our lives comes shortly after that day on the pier when we go out to a party together and my future—in the form of an exotic black goddess named Jackie—sees me checking her out and gives me a look. She is five-ten, statuesque, stacked, wearing a shimmering dress like she’s poured into it, just oozing sexual energy. And without hesitation or premeditation whatsoever, I reach over, grin, and grab her ass. My favorite kind of ass, it feels just like a basketball. My hand lingers. She doesn’t slap me, doesn’t flinch. Just raises her eyebrow and smiles. As if to say, What took you so long to find me?

I hurried headlong as a door opened into a world that promised absolute sexual joys I couldn’t even begin to imagine, a world that was also destined to turn into a horrendous nightmare, and that’s putting it lightly.