EPILOGUE:

WE WILL REMEMBER THEM

An age of Death and Agony and Tears,

A cruel age of woe unguessed before —

Then peace to close the weary storm-wrecked years,

And broken hearts that bleed for evermore.1

For the men who returned it was a different world. Old values were gone. Their youth had been stripped from them. They had seen so many men killed and maimed. They had lived in filth with the threat of death ever-present. They had killed. They had developed a comradeship that few civilians could understand. To return to the familiar yet changed world from which they had come was not easy; for some it would prove all too challenging.

For Allan and Percy, returning home was made more difficult by the loss of their three brothers. Their world had been torn apart and their lives transformed; leaving their brothers behind was the most difficult task of all. They returned to a home torn apart by war, to shattered dreams and broken hearts. They had to learn to live in peace, to sleep under a roof at night, possibly to relive the horrors of war in that sleep and to confront the realisation that honour and glory fade quickly. The bonds the family shared eased the process of adjustment, as did the continued comradeship and understanding of the few neighbours and friends who had also served and survived.

For a short time, Allan remained on the family farm at Mologa. Percy returned to ‘Hayanmi’, a property a few kilometres south-west of Mologa which belonged to his aunt and uncle, Florence and Arthur Mahoney, the brother and sister of Sarah Marlow. He would farm there for the rest of his life.

On 24 March 1920, the men of the Gordon Shire (east of the Loddon River) who served Australia were officially recognised and honoured for their courage and sacrifice with the unveiling of a handsome memorial. The event was reported in the Pyramid Hill Advertiser:

The residents of this district have worthily placed on record their estimation of their soldiers by erecting a handsome stone column, which was unveiled on Wednesday 24th, by Mrs C. Marlow, to whom the honour was justly due, as is well known, by the fact that five of her sons volunteered, of whom three are in soldier’s graves in France … In the unveiling ceremony Lieut. A. Marlow escorted his mother on to the platform and the large assemblage stood bareheaded as the cords were cut and the covering Union Jack removed from the pedestal.2

Allan and Sarah Marlow unveil the Mologa War Memorial.

Every city, town and hamlet in Australia has its own memorial, erected in recognition of those who served their country, particularly those who died. So much hope rested on the shoulders of this young generation of soldiers. Each family’s loss was also a loss to the entire community.

After the unveiling of the memorial, the family continued to receive letters concerning the loss of their sons for some time, a few from family, some from complete strangers.

Water Farm

Sept 15

Manaton

Moretonhampstead

My Dear Nephew

Very many thanks for your kind letter I received this morning please forgive me for not writing sooner to thank you for the papers also the photos you sent me I received them quite safely it was nice [of] them giving your mother the honour of unveiling the memorial but it must have been a very trying day for her to think of her Dear boys lyeing so far away I should like to have known George & Albert we often think of poor Charlie I did think Allan would have sent us a line before now we hope both he & Percy are quite well. We are very sorry to hear your mother has been so ill I hope by now you have her at home again. Well you would all miss her very much I am very glad the operation has turned out so well. It does seem so funny to us for you to write about it being winter. I hope you have had some rain by now. We and people around here have had very poor crops of oats and wheat but of course this land is not suited for growing heavy crops … I hope you will leave & see it some day but I don’t expect you will this country is in a very funny state I can tell you every thing is very Dear I am afraid their will be a lot of suffering amongst the poor people in the towns this winter we had your Aunt Lizzie & her son Clem for 10 days a short time ago he is in Ireland now there is tough work going on their give our love to your father & mother Allan & Percy. I am afraid Dear Jim my letter will not be of much interest to you not knowing the place. I will close with love to all from your loving Aunt A Lee

Over 12 months after the end of the war, Sarah received a letter from one of Charlie’s mates. The author, John Wright, writes with some reluctance, afraid of causing Sarah further grief. But he is keen to fulfil a promise made to Charlie:

72 Fawcett St

Mayfield

Newcastle

18-1-20

Mrs C. Marlow,

Mologa Post Office

Dear Madam,

As this is a very sad and delicate subject I wish to write about, I hope you will forgive me if I reopen any partially healed wound in so doing. When in France in March 1918, I was with your son, Sgt. CE Marlow, near the village of Neuve Eglise, and as we mated together we exchanged numerous confidences. He knew that I had my camera with me, and, as we were near the cemetery of Kandahar he asked me if I would photograph the grave of your Son, and, if possible send it to you. This I did with the enclosed results. You will be able to have an enlargement taken from the negative, as it is pretty clear. You will, I am sure, realise the spirit with which I send this souvenir to you. My Mother, had the positions been reversed, would have only been too pleased to have a photograph of the last resting place of her Son. I did not know this boy of yours, as I was in the 35th Battalion, but Charlie, I found was a thorough gentleman in every respect, and any one that knew him will bear out my statement. Mother, father, my wife and I, join in sympathising with you for the loss of a brave son who answered his country’s call.

I remain

Yous sincerely

John G Wright

The photo Charlie asked John Wright to take of Albert’s grave.

On 18 March 1921, the Pyramid Hill Advertiser published a letter sent to the Marlows from England:

Mologa Soldier’s Grave

English author’s kind thought – Mr C Marlow of Mologa who is father of the late Cpl. G.T. Marlow, who lies buried in Belgium. – The well known English novelist and poet, John Oxenham, and his daughter, recently visited an Australian graveyard in Belgium and seeing the grave of Cpl. Marlow have sent to Mr Marlow the following touching letter:

Woodfield House

Ealing London

Dear Mr Marlow,

You do not know us nor we you, but we are full of gratitude for the great sacrifice you made in the great war, and so, as the distance may prevent you from coming yourself, we have been across to Belgium to visit the Australian graves, including the grave of your son, and to tell you a little about the place where he lies. We hope it may be comforting for you to think that an English girl and her father have visited it on your behalf. Cpl G. T. Marlow, No. 2748, 2nd A.L.T.M.B. lies in plot 23, Row B, in Lijssenthoek cemetery just outside Poperinghe, some 9 miles north of Ypres. It is a place of restful beauty with green trees and a stream on one side, and hop fields and rolling meadows and ploughed lands with red-roofed farms beyond. At times there is not a sound to be heard. The body of your loved one rests in perfect peace after the hardships and trials of war. But we know – as we are sure you know – that he himself, his real self, is infinitely happier where he is than ever he could have been on earth at its best. The graves are planted with roses, violas, pansies, wallflowers, lupins, clarkia and marigolds, with trim grass walks between, and all are most carefully tended by a staff of gardeners, who also keep a large nursery for the sole purpose of supplying the graves with fresh plants. Nothing is wanting in loving regard for those who have gone. We enclose a photograph of a part of the cemetery and with sympathy and love remain

Yours sincerely

Erica Oxenham

John Oxenham3

John Oxenham was a prolific English writer, poet and journalist whose real name was William A. Dunkerley. Erica was also a writer. Their kindness in writing to the families of fallen soldiers is extraordinary. One wonders just how many letters they wrote to bereaved families all over the Commonwealth.

‘Passchendaele’, Mologa, 1985.

Some four years after the unveiling of the memorial, Allan married Eva Jones on a rainy 24 September 1924. They are my grandparents. The bond formed in their letters blossomed into a loving relationship following Allan’s return. Grandma once told me that, on the day she opened the letter containing Grandpa’s photo, she knew he was the man she would marry.

Their new mud-brick home on the railway line between Mologa and Mitiamo was not completed until April the following year. It took some time to construct as Allan made the mud bricks and built the home himself. The kitchen sported a grand pantry in which Eva kept the baking which Allan had so appreciated, a welcome comfort in the appalling trenches of the Western Front. The cakes and biscuits were neatly stored in rows of tins.

Allan named his new home ‘Passchendaele’, scribed lovingly in stained glass above the front door. His house represented his own monument to a dreadful carnage, the home a haven which provided a stark contrast to his memories of the horrific Battle of Passchendaele. The remains of the house today exist as a haunting reminder of an experience that only my grandfather and other veterans of that terrible conflict can truly appreciate and understand. Each man emerged from the war with his own unique reflections and recollections. Perhaps ‘Passchendaele’ stood to remind us all of the tragedy of war and the peace we should fiercely protect.

Despite the name he gave his house, Allan appeared determined to forget and to live in peace with his family, although forgetting was never really possible. He chose to sleep in a purpose-built sleep-out of screened walls attached to the main family home; he struggled with enclosed spaces, a legacy of being buried alive in April 1917. He rarely spoke of the horrors he had witnessed and chose not to attend RSL meetings. During the Second World War he joined the Volunteer Defence Corps, an organisation of volunteers, largely trained by World War I veterans, who would assist in the defence of the homeland of Australia, should it prove necessary. My father remembers the targets at Mitiamo Rock in the Terrick Terrick Forest above Mologa. There Allan and other returned soldiers would instruct the volunteers, preparing them for what could have been a crucial role in the war.

Eva Marlow aged 16 in a photo dated 9 July 1916.

After his mother’s death in 1935, Allan no longer attended Anzac Day ceremonies. Sarah, like so many others, had not recovered from the anguish and loss of the horrific years of war. Perhaps the memory was just too painful; irrespective, the war had taken yet another member of the Marlow family. When asked, the family always told me that Sarah had died from a broken heart. Having followed her journey through the war, I now understand what they meant.

Allan and Eva Marlow on their wedding day, 24 September 1924.

The Pyramid Hill Advertiser reported Sarah’s death:

The blows of bereavement undermined the health of this mother of warrior sons, and later years there were recurring attacks of weakening indisposition. As late as yesterday week the late Mrs Marlow was attending to her regular duties about the home and afterwards complained of general weakness, but none thought she would never arise from her bed again …4

The day Sarah Marlow was buried at Pyramid Hill, returned soldiers formed up at the cemetery gates and marched ahead of the pallbearers.

Charles senior died 15 years later on 18 April 1950 at the age of 93. He was buried with Sarah at Pyramid Hill.

As it shattered the heart of Sarah, the war also hastened the demise of the township of Mologa. Prior to World War I, the town had been a thriving community. But the lifeblood of many of these small towns had been spilt on the soil of France and Belgium. The Great Depression saw the town slump further and it never recovered. As a child, I recall passing the dilapidated hall and school, post office, railway siding and war memorial. Today, the memorial and decaying school are all that remain. But Mologa is not forgotten, nor are the soldiers who fought so gallantly so far from home. In recent years, my Uncle Allen and Gwen Gamble of Mologa, whose father was veteran Amos Haw, have reinvigorated the memory of Mologa’s lost sons. Anzac Day services at the memorial recommenced some years ago and the numbers who arrive in the chilly pre-dawn are growing every year.

The Mologa Memorial in 1984. Little remains of the township of Mologa today.

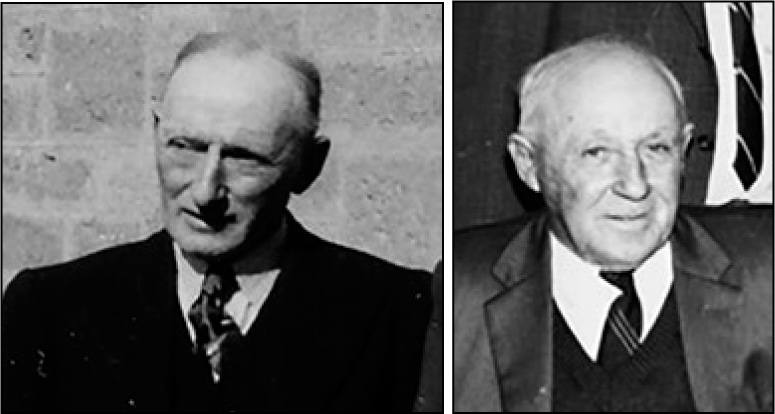

The older Allan in his twilight years (left). Percy later in life (right).

Percy died after a short illness on 20 October 1973 at the age of 78. His brother Jim, the eldest son, suffered a stroke and died five years later on 9 June 1978; he was 88 years of age. In 1924 he had travelled to Europe to pay his respects to his brothers. Neither Jim nor Percy ever married. I am told that Percy once argued with the love of his life and they were never reconciled. Of six sons who reached adulthood, only two went on to create a new generation. One of those, Charlie, would never meet his daughter. When Jim passed away, the family gradually lost contact with Pearl and Eva.

* * *

The deeds of the Australian soldiers of the Great War transformed a nation. They established a tradition, creating a unique identity and giving a young nation its soul. But this came at an unimaginable cost. The spirit of those who never came home lives on in their legacy. Those who survived are no longer with us to tell their stories, but their memories are very much alive in their letters and their words. May they and their stories live on in the hearts of those they leave behind, for they forged a legend that we can never forget.

Have you forgotten yet?

Look up and swear by the green of the Spring that you’ll never forget.

Siegfried Sassoon, Aftermath, March 1919