8.

Frank

Your father’s busy.”

“But he’s always busy,” I said. “What’s he doing?”

“He’s busy and he’ll be busy all day. Now try not to disturb him. Go and play, go and read a book, go and do something.”

My mother was standing in front of the door to the sitting room with her arms crossed. I knew the television was on, I could hear it. My father was clearly watching sports, and I didn’t think that qualified as “being busy.”

It’s amazing how many hours my father spent watching sports. If only I could one day have a job where I could get away with that—now that would be cool. Dad was watching cricket and, when I eventually snuck in, quietly as I could, he explained the game to me.

I can’t pretend I grasped it the first time, and I made him draw me a diagram of the fielding positions, which I then had to hold upside down for alternate overs. But I did believe him when he said, “This is an historic event.”

Dad played the shots that the batsman should be playing and imitated the spin bowler’s wrist action. He marveled at the grace and the speed of the West Indian bowlers—this was the great side of the eighties captained by Clive Lloyd, backed up by the likes of Viv Richards, Michael Holding, Joel Garner and Malcolm Marshall. After telling me who everyone was and what they should be doing, he growled or grunted after each ball, and then he was quiet.

“Out!” I said, loudly, ten minutes later.

“What?” My father woke with a start. He was apt to sleep a lot when he was watching history in the making.

“Boycott,” I said. “He’s out. No great shame as he was scoring so slowly.”

I could feel my father’s eyes on me, so I looked at him. His mouth was open slightly and then he nodded. “That’s probably true.”

“Gooch is still there. I like him. But you’re right about that Whispering Death fellow. He shifts the ball, he really does,” I said, folding my arms.

“Good girl,” my father said.

Well, I didn’t think it was that difficult, frankly, to have an opinion that seemed to be right. You just had to listen to the commentators, watch what was going on, know who was who, and away you go. It’s hardly rocket science. When rain stopped play at the Oval, I wandered off to see Frank.

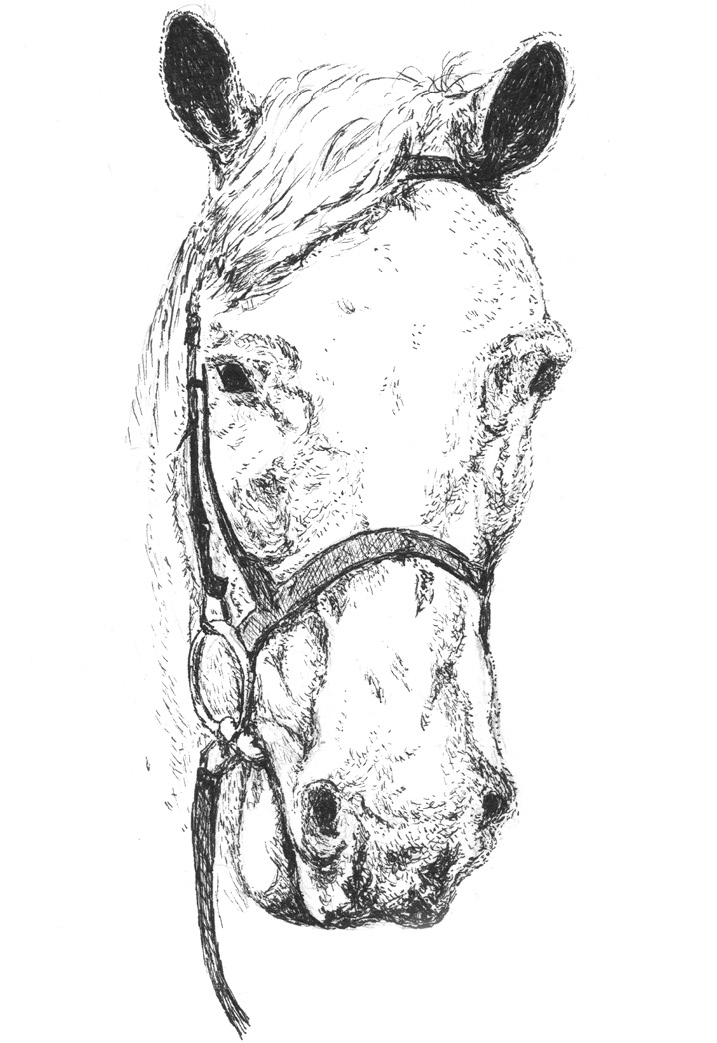

Frank was the ugliest pony I ever had. When he arrived, he was called Prince, but that seemed inappropriate, so we named him after Frank the Box Driver.

He had a short, spiky mane, rubbed raw in places, a pink nose, pink eyelids, brown ears and a gray body with brown splotches down his neck. His bottom and his sheath were pale pink. He suffered from sunburn, so had to have liberal applications of sunblock on his nose in the summer. He was what they call a “Heinz 57.” That’s not a can of soup, it’s a mixture of various different breeds. Frank was nothing, and he was everything.

His mouth was as sensitive as a block of wood, and he frequently took hold, putting his head slightly on one side and galloping off in whichever direction took his fancy. He was not straightforward, he was not handsome and he was not even affectionate, but I adored him.

Frank understood me.

Fine, he trod on my feet and barged me out of the way when he wanted to get out of his stall. Yes, he never looked clean and we were the laughing stock of the Pony Club. Yes, I wasn’t allowed near the racehorses with him because they all spooked and whipped around because he was “a freak.”

I loved him with a passion of which I had no idea I was capable. I loved him partly to defend him against the world and partly because I genuinely believed we were soul mates. If I had ever thought it was likely that my mother might sanction me having a tattoo, it would have read “Frank.” Instead, I carved it into the bark of the Hollow Tree at the top of the Downs:

CLARE LOVES FRANK, 8/1/80

In the years to come, I figured, people would see that inscription and know how much I cared.

Where other girls my age had posters of tennis players or pop stars on their walls, I had photos of Frank. I had long, long conversations with him about life at school and how much Andrew annoyed me; I told him England had drawn the Fourth Test and I admitted to him that I suspected my grandmother hated me.

I was allowed to ride on my own now, as long as I told someone where I was going. The trouble was, there were so many options, it was hard to say exactly where I might end up. I could ride on the farm, up to the Downs, over the hill to Hannington, go through the water at Gaily Mill and hack over to Ecchinswell, trespass just a bit on the edge of the Lloyd Webber estate or stay close to home and use the all-weather gallop just before Jonna harrowed away the hoof prints, to make it fresh and fluffy for Second Lot. Wherever I went there were jumps, built for the drag hunt, so I could fine-tune my eye, seeing a stride from farther and farther away.

The Berks & Bucks Drag Hunt had been established by a group of adrenaline junkies keen to gallop and jump, happy to ride to hounds but wanting to avoid the unpredictability of fox hunting. Three or four “lines” were preplanned, with fences built or hedges trimmed to allow a field of up to eighty riders to gallop and jump across country. A runner with a sock soaked in aniseed marked out the line by laying a scent trail, which the hounds followed.

For my father, the drag hunt was the ideal option. It happened on a Sunday, so he was unlikely to be racing; it guaranteed him a rush from jumping at pace and it rarely took longer than three hours from beginning to end.

“Dad, when can I come drag hunting?”

My plea became ever more persistent. I had been out to watch my father on his big chestnut, Paintbox, and my mother on her rather plain hunter, Ellie May, and I so wanted to join in. I knew Frank would love it.

“There’s a children’s meet in the spring. You can come then,” my father conceded eventually.

He was the Field Master, which meant he wore a bright-red coat, confusingly referred to as a “pink” jacket, and he led the field. The rule was that you had to stay behind him and you had to listen to what he said. Dad had never been in the army but this was the closest he ever came to being a general, barking orders, leading his troops and generally enjoying the authority.

My father was a fearless rider. He liked to do everything at racing pace, and he rode short, even in a hunting saddle. If you could stay upside my father and jump what he jumped, you earned his respect forever. This was my ambition.

Our ponies were now being kept at the stud, where the mares and foals lived. It was a short walk away from the yard and from the house, with a different team of people running it, and all of it was fiercely protected by my mother. This was her territory—she had bought the stud from Grandma, and it was up to her who worked there and which horses were kept there.

The stud had two yards, and the one on the left, where our ponies lived, was built in red brick in the same style as the John Porter racing yard, but was more compact and much friendlier. Horses and people walked through an arch into a small quadrangle with ten stalls in total: four on either side and one at each end. The tack room was on the left of the top arch and the feed room to the left of the bottom arch. The horses all looked out into a central square, laid with red clay, with a large pot, planted with marigolds, sitting in the middle. The stable doors were painted green, the stalls spacious and solid. It was, and still is, the perfect yard—quiet, functional, warm and fine-looking.

It was also a great place to keep two tearaways out of trouble. Andrew had a dappled iron-gray pony called Raffles who did everything at 100 mph. Raffles could jump a house if he had to, but he was always on the limit. To be totally accurate, he was always out of control, except when he was show-jumping. Andrew had been studying the great show jumpers of the time—Eddie Macken, Harvey Smith and Paul Schockemöhle—and had developed a rising canter, which he liked to use in the arena. He would move up and down, as if in trot, while Raffles cantered along.

For a while, Andrew wanted to be a show jumper—but he had also wanted to be a fireman, an astronaut and a Jedi knight, so we took his career choices with a pinch of salt. It was when, at the age of eight, he announced that he wanted to be a racehorse trainer that something happened. It was as if the wind had changed direction, or that smell there is when it’s about to rain had come.

My father began to have serious conversations with him about the horses, and my grandmother started sentences with the words “When Andrew’s in charge . . .” or “When Andrew lives here . . .” It wasn’t that my brother became someone else—he was still motivated by pizza, chips and chocolate—it’s just that everyone else seemed to change their attitude toward him. It was as if he mattered now.

I caught snippets of whispered conversations about Andrew’s future as the master of Park House.

“Well, thank God he wants to do it,” my mother said.

“Of course he wants to do it. What kind of idiot wouldn’t want to do it?” was my father’s clipped response.

Any suggestion of a life other than the one my father had led perplexed him. Being a racehorse trainer was surely the most valuable, important and respectable job on the planet.

Women were allowed to hold a training license by now, thanks to the efforts of Florence Nagle, who had fought hard to persuade the Jockey Club that, even though she didn’t wear trousers, she could still train a racehorse. There were a few female trainers around—Jenny Pitman started training in 1975 and won the Grand National in 1983 with Corbiere; Mercy Rimell took over from her husband, Fred; and Mary Reveley had consistent success over many decades. But, in our household, training was a man’s job.

Andrew read the Sporting Life and the Racing Post every day. He could work out fractions if it was computing his winnings from a five-pound bet at 6–4; he knew how many lengths to a pound over a mile and how it differed over a mile and a half; he remembered the effect of the draw at Chester or Doncaster; he understood weight for age and weight allowances for fillies. He could suddenly speak a language that allowed him to communicate with my parents and with Grandma. I listened to them all and nodded occasionally, saying things like, “Makes sense to me.”

But none of it did. I just didn’t get it, and I hated it because I didn’t understand what they were all going on about and why it was all so important. I resented that every conversation was about which horse was running where, who was riding it and which one of them was going to saddle it. No one read a proper newspaper or watched the news. Nuclear war could’ve broken out—we were near enough to Greenham Common for it to be all too real a prospect—and none of them would have noticed unless it meant that Royal Ascot was canceled. The world revolved around racing and, if I wasn’t in, I was out.

Once Andrew had decided he wanted to train at Park House, it was clear that I was going to have to find something else to do with my life. I was ten.

I talked it through with Frank. Well, I talked. He listened, brown ears flickering back and forth.

“I’ll show them,” I vowed.

I was riding on the farm, where twenty or so drag-hunt fences had been trimmed up, ready for the children’s meet. I squeezed him in the belly and we sailed over the tires, the timber and the barrels by the side of the Range Road. I patted Frank on the neck and slowed down to a trot, then let him open up into a stronger canter on the grass of Long Meadow. This is where I felt alive—with the wind in my face, galloping and jumping with Frank.

My beloved Frank devoured solid cross-country fences, but show jumps were a trickier prospect. He wasn’t at all sure about colored poles. For our first Pony Club event, Liz, who was working at the stud, had helped me wash Frank with soapy water. We had attempted to braid his spiky mane and make the best of his dreadful tail. Poor Frank looked like a farmer forced into a morning suit—it wasn’t him at all. Nevertheless, we trotted into the show-jumping arena.

“Next into the ring,” said the announcer, “we have Clare Balding riding Prince Frank.”

Mum and I had decided that we ought to at least give a nod in recognition of Frank’s former name, just in case it really was unlucky to change it.

I sat into the saddle, took a strong contact on the reins and squeezed Frank into a collected canter. The bell went. We found a lovely rhythm and cantered into the first—red-and white-striped poles. I thought we met it on the perfect stride, but Frank didn’t really take off and crashed straight through it. Thrown off balance, I nearly fell off but picked his head up off the floor and on we went.

The next was a rustic brown fence and he sailed over, then a blue-and-white oxer—crash, the back pole came down. Into the green-and-white double and Frank brought the first part down with his hind legs, the second with his front legs, the pole coming with us for two more strides.

I didn’t know what to do apart from keep going. The plain white or rustic fences were fine, but the colored ones he smashed to pieces. We finally finished; I patted Frank on the neck and the announcer said, “An interesting round there for Clare Balding and Prince Frank. Thirty-two faults. Don’t think we’ll be winning any prizes with that.”

My face turned bright red as we trotted out of the ring. I could tell from looking at my mother that she was in shock.

“I just don’t know what happened,” I said. “He jumps so well at home and he was fine in the collecting ring. Something must have scared him.”

“Never mind,” my mother was saying. “Poor old Frank, maybe show-jumping’s not for you.”

From across the horse trailer park, I had just caught sight of a woman running. She was making a strange sound, like a goat bleating.

“Oooh, ooh, ooh. It’s Prince. It’s my beloved Prince.”

She had flung her arms round Frank and was kissing him on the neck. He looked bemused and I felt a pang of something I would later identify as jealousy.

“Hello,” said my mother, as politely as she could. She didn’t do well in the face of public displays of affection. “Can we help you?”

“I heard the clattering,” said the woman, “and I thought—I only know one pony who could knock down that many show jumps.”

She stroked him gently as her words came tumbling out.

“Oh, I thought he’d died. I thought I’d never see him again. Where did you find him? How is he? Where’s he been? Did you know about the animal-testing place? You do know he needs sunblock, don’t you?”

The questions came so fast I couldn’t take them in, but it emerged that this woman, Sarah, had ridden Frank when she was a little girl. When she grew out of him, her father promised he would find him a nice home but, in fact, the pony had been earmarked by some scientists who had noticed his extra-sensitive skin. They wanted to test creams and potions on him and offered £1,000 for him to go to an animal-testing unit near Newmarket. Her father had accepted. When Sarah found out, they had a huge quarrel and she left home. She had not since spoken to her father.

Frank—or Prince, as she called him—had been rescued from the animal-testing place by a trainer called Frankie Durr, had gone through various racing families and had ended up at Swindon market, where my mother had bought him for £500.

“It’s the colors,” she was saying. “He’s scared of the colored poles. You’ll find he’s fine with plain ones, but stripes and all that—he hates them. Oh, I’m so pleased you’ve got him. You will keep in touch, won’t you?”

Sarah scribbled her address and phone number on the show program and thrust it into my mother’s hand. She kissed Frank on the nose and she was gone.

“Well, that was an experience,” my mother said, as she filled a bucket with water. “An animal-testing unit? Poor old Frank.”

Mum sent Sarah a letter every few months with a photo of Frank to let her know what we were up to. I tried to accept the fact that I was not the first to love him, and I hoped that Sarah would keep her distance. Over time, I realized that, as Frank couldn’t read her letters, she was not a threat.

~

The day of the children’s meet was upon us. This was the one day of the year when children were actively encouraged to go drag hunting. The fences were smaller than usual and you could go around them all if you had to. Dad had given Andrew and me a stern talking to. We were to listen to him and to stay right behind him.

I was so excited I had barely slept the night before, and I arrived at breakfast dressed in my beige jodhpurs, my shirt and my Pony Club tie. I had, however, learned my lesson. They were covered by a scruffy pair of jeans and a sweatshirt so I could get as dirty as I needed to, peel off the top layer and be spotless underneath.

Andrew didn’t mind so much, nor did he intend to do much in the way of preparation for Raffles. If he was nervous, he didn’t show it. I couldn’t stop chattering on about what we were going to jump, who would be coming, which lines we were doing and how much I thought Frank would enjoy it. Andrew sat there, stuffing toast into his mouth, grunting.

Dad was out putting up signs directing people where to park and trying to make sure they didn’t turn their horse trailers into the main entrance of the yard. He kept running back into the house, slamming the back door and shouting, “Emma!” at the top of his voice.

He had left something behind, or lost something, or forgotten someone’s name. This needed to be solved, immediately, by my mother. Mum was getting Andrew’s things together, so I headed off to the stud to start preparing Frank for the big day.

Liz, our supersonic groom, had already done most of the work. Liz did things very fast. She even walked fast, like Patrick Swayze in Dirty Dancing, or Andre Agassi, with short steps. She had curly brown hair and a round face. She never seemed to lose her temper and was so happy every day just to be paid to be working with horses. Liz had cleaned our tack and groomed our ponies, so all I had to do was put on Frank’s tack while I told him who was coming, and paint on his hoof oil. I stood back to admire my wonderful pony in all his glory.

“Ah, well, you can’t polish a turd.” My father had arrived in the yard. I had no idea what he meant, so I just sighed and said, “Doesn’t he look smart?”

“I suppose that’s one way of describing him. Now where’s your lazy brother?”

Dad was wearing his bright-red jacket with gold buttons, white breeches and gleaming black boots. He carried a hunting crop and there was a horn in a leather pouch to the side of his saddle. Paintbox, with his white face and his shiny chestnut coat, looked magnificent. And huge. He was a big horse who pulled so hard no one but my father could hold him.

I got on Frank, but there was still no sign of Andrew. Raffles was all ready in his stall, so I suggested we lead him up to the house to save time. As we headed up the path, my mother appeared, dragging my brother behind her. His shirt was hanging out, his tie had egg on it and his jodhpurs were too tight. He had spilled butter and Marmite on his smart jodhpurs so was now wearing brown ones. They would at least hide the dirt.

“He went back to bed,” Mum explained as my father made a low, growling sound, the same sound he made when a puppy peed in the house.

We rode together to the meet, in the field behind our house. There were loads of children on ponies, their parents on foot looking rather anxious. Andrew and I stood on either side of Dad for a photo and then he hollered at the assembled masses, “Gather round!” I always thought it was a good thing my father had a loud voice, because he seemed to do a lot of shouting.

“Welcome to the children’s meet here at Kingsclere. It’s lovely to see so many of you. We have four lines today and there is an alternative route round every jump so, please, if your pony decides it doesn’t like the look of something, just go round it. There are certain rules that we all need to follow for safety, so listen carefully while I take you through them . . .”

As Dad listed all the things we couldn’t do, Frank and Raffles both started to get edgy. They wouldn’t stand still, so Andrew and I peeled off from the gathering and took them for a trot around the field.

“There’s no point us listening,” said Andrew. “We’ve heard it all before.”

Raffles had a Balding gag in his mouth, a gag invented by our great-great-grandfather. It’s a bit with holes in the rings on either side and a piece of rope going through them which pulls down on the poll so that the horse lowers its head when the rider pulls on the reins, in theory making it easy to slow the horse down.

Dad had finished shouting, for now, and the hounds moved off with the Master, Roger Palmer, in his red coat at the head of them, and four more people around the hounds. They were “whipping in,” so it was their job to make sure the hounds were following the scent and staying on track.

The first line started on the farm, went down the Range Road, left up Long Meadow, through Smith’s Bushes and finished at the end of a long climb at the top of the Downs. My father thought it would take the sting out of the ponies who were too fresh and pulling hard. This was a good plan, but what he hadn’t foreseen was the downhill end to the Range Road and the sharp left turn. With fifty ponies all charging together, this turned into a Grand Prix-type chicane and hairpin bend.

Dad let the hounds get well ahead and then, with one last holler at everyone to stay behind him, he set off. I was right behind him and heading toward the first set of tires in relative control. I thought Andrew was with me but Raffles started dancing on the spot as he heard the horn of the Master. He was rearing slightly and jumping up and down, so Andrew gave him a kick in the belly and loosened his reins a notch. That was an invitation Raffles could not refuse.

The round-bellied little monster took off. As we jumped the second fence I could hear Andrew screaming as he flew past me. He took the third fence upside Dad, who shouted, “Do not go past me, I said, ‘Do not—’” he realized who it was “—Andrew, pull him up, pull him up. Turn left, left!”

Andrew had never really gotten the hang of left and right, so he went one way and then the other and ended up going straight on. At the bottom of the Range Road is a double-width six-bar white gate. It’s for the tractors and combine harvesters to come into the farm from the Sydmonton road. It’s over five feet tall and made of iron. Andrew and Raffles were heading straight for it.

Raffles cleared the gate in style but, as they landed on the other side, Andrew fell off—more out of shock than anything else. My father put his hand in the air to signal to the rest of the field to stop and called over the gate, “Are you all right?” Andrew nodded and bit his lip. “Right, catch that damn pony and stay at the back. Clare, you look after him. The rest of you, follow me.”

With that, the Field Master, our father, took the field and headed up Long Meadow. I opened a small wooden gate to the side, told Andrew to wait there and went trotting off toward the village. I found Raffles not far away, munching grass at the side of the road.

Andrew and I could see the field disappearing up the hill to the Downs, so we hacked along together, jumping all the fences up Long Meadow. By the time we’d caught them up, Mum was anxiously looking for us. Despite much hurrumphing from Dad that “the boy should carry on—it’ll be good for him,” she decided to take Andrew and Raffles home.

Over the next three lines, I stuck right behind my father. Frank was brilliant. He put in short strides, saw long ones, met most of the fences just right and didn’t even pull. When we got to the Team Chase fences, Dad said, “Come on then, girl, get right upsides me.”

We raced the whole way up to the top ring, Frank and Paintbox side by side, the one tall and handsome, the other squat and ugly. Dad turned to me as we pulled up, and grinned.

“Handsome is as handsome does, I suppose. You’re quite some pony.” He was smiling at Frank.

I felt so proud as we headed home. I was flushed with excitement; Frank was still high on adrenaline so refused to walk but jig-jogged the whole way back. We were covered in mud, flecks of sweat and froth, but we were happy.

My Frank wasn’t born to jump colored poles in smart show-jumping rings. He was born for this.

~

Grandma was not a fan of Frank’s. By way of introduction, he had stood on her toe and butted her hard in her considerable bosom.

“That pony is unattractive and ill mannered,” I heard her say to my mother. “I suppose they’ll suit each other well.”

I had been reading enough adventure books to think that it would take just one act of heroism for both Frank and me to turn Grandma in our favor. We just needed the opportunity.

That chance came on a murky evening in 1980, right at the end of the summer holidays. Grandma’s favorite dog was called Dusk. She was a small, fine-boned black whippet and a law unto herself. She would take herself off hunting for hours on end and, on this particular evening, she had been gone for longer than ever. Grandma had walked to every spot she could think, she had whistled and called, but there was no sign of Dusk.

Seeing my chance to be the hero of the hour, I said, “Don’t worry, Grandma. Frank and I will find her.”

Grandma was standing in our kitchen with her husky jacket on. Andrew was forcing cake into an already full mouth. My father was out in the yard and my mother was chopping vegetables she had picked from the garden. None of them seemed to hear me as I waved a cheery good-bye and headed off to tack up Frank.

We rode over to Grandma’s side of the road, along the boundary hedgerows, through Smith’s Bushes and up to the Downs, back down the chalk track, through the farm and over to the avenues, under the hill and down the Far Hedge, me calling all the way, “Dusk! Dusk, where are you?”

After an hour, it started to rain. Then it began to pour. It was getting so dark I could only just make out the white furlong-marker poles on the gallop to our left. There was no sign of Dusk and, even in my fervent desire to be a hero, I could tell we were doing ourselves no favors. We were only going to get wetter and colder. The dog had disappeared.

Frank was supposed to be turned out at night. He was allergic to straw and all the stalls at the stud were full, so I took him up to the row of four stables by the tennis court. He had been such a good boy and I couldn’t bear to turn him out in such filthy rain. The least he deserved, I reasoned, was a warm, dry bed for the night.

The stalls were empty and had no bedding at all. I left him standing while I carried his saddle and bridle to the tack room and then I set about my work. Andrew and I hardly did any mucking out because Liz did it all for us, so neither of us were particularly good at it, but I did know how to lay a decent bed and I was determined to do so for Frank that night. Evening stables had long since finished and there was no one around. The lads were back in their houses or watching TV in the Hostel.

In the barn at the end of the row of stalls were some paper bales wrapped tight in black plastic. They were for racehorses with respiratory problems, because there is less dust in paper than in straw, so I figured one of those would be perfect for Frank. I split open the bag with a knife, placed it carefully back on the windowsill and picked the sharpest, shiniest pitchfork leaning against the wall.

I raised it high above my head and speared downward through the paper bale. It felt as if it had got slightly stuck and I thought it must’ve gone right through to the ground, so I pulled it back out, with some difficulty, and then scooped under the paper to carry it to Frank’s stall.

As I started walking, I felt an odd sensation in my left foot. It was really itchy. When I got to the stable door, I put down the chunk of paper, leaned the pitchfork against the wall and reached down. I had to pull my boot off, because my foot felt really odd. Something was wrong. I can’t remember if I saw the blood on my sock first, or the blood on the blade of the pitchfork but, either way, it made me feel sick. Like a tap being turned on, pain suddenly coursed through my body, and I collapsed against the frame of the door.

Frank came over to nuzzle me and butt me in the ribs.

My foot hurt so much I had to stifle a scream. I couldn’t put my boot back on, so I hopped to the nearest dwelling, which was the mobile home on blocks of concrete where Spider, the Traveling Head Lad, lived. Luckily, he answered the thud on his door.

“Oh dear,” he said. “What have you been up to, young Clare?”

“I’ve had an accident,” I replied, as calmly as I could. “I was out with Frank, trying to find Grandma’s whippet.” I was whispering, but I thought it was important he knew the context. “He was so good. So good. Didn’t want to turn him out in the rain. Not fair. Was making him a bed. Pitchfork. Foot . . .”

My voice trailed off and I was falling backward, sliding out of consciousness. I felt an arm behind my head and another one under my knees. Spider had caught me and the next thing I realized was that we were heading down the gravel path by the runner beans. He was carrying me back to the house.

My mother answered the front door to see Spider standing in the rain with me in his arms.

“Oh God—what’s happened?” said my mother. I was coming back into the world to see Grandma over her shoulder, standing in the hall.

“What’s she done now?” said my grandmother. “Honestly, such a drama queen.”

“I couldn’t find her, Grandma. We looked everywhere, but I couldn’t find her.” My voice was small. I felt as if I was removed from the scene, looking on from above.

“She’s stuck a pitchfork through her foot,” Spider told my mother as he carried me into the house. “There’s a lot of blood, but I don’t think it’s broken. She’ll probably need a tetanus shot.”

“Thank you so much,” said my mother. “I’m sorry she disturbed you.”

“What do you want doing with the pony?” said Spider, laying me down on the sofa and backing out of the sitting room. “The ugly one—Frank?”

“Turn him out in the paddock at the back,” said my mother.

“No!” I thought I had shouted it, but no one seemed to hear.

Mum sighed; a big, deep exhalation of air. A “why?” without words.

“You silly girl. We’d better get you to the hospital.” My mother was in practical mode now. There was to be no fussing. I had done a stupid thing and it would have to be dealt with. There were people coming for dinner and it was damned inconvenient.

Luckily, the prong of the pitchfork had slid between my second and third toes and missed the main chunk of pedal bone. The curved blade meant that it came out the other side farther down my foot than it went in. I still have scars on top and bottom as a reminder.

Dusk was never found. Grandma is convinced she got caught in a trap or stuck in a rabbit warren. The next day she brought over a packet of Polos for Frank to say thank you.

~

My funny-colored Heinz 57 got over his fear of colored poles and became quite a good show jumper. We went to Pony Club camp together, where we won the Thelwell Prize for pony and rider most like a Thelwell cartoon. I was thrilled. (Andrew won it the following two years.)

Frank and I had a 100 percent clear round record in hunter trials. I took him drag hunting whenever I was allowed and Andrew and I rode in pairs competitions together. Mum said she could hear us shouting at each other from two fields away as we argued about who should be leading.

When I got too tall for Frank, Andrew rode him for a year, but then he got into polo and the day I dreaded had come. I cried all week leading up to it. We were giving Frank to a sweet little girl who I knew would look after him and remember to put sunblock on his nose, but I couldn’t bear to see him go. He trod on my toes, just for old times’ sake, as he was loaded onto their horse trailer. Then he backed up against their sparkling-clean wall and did the runniest, greenest dropping all down it and down his legs.

Despite his propensity to make himself look his worst, despite the fact that he had no manners and no particular affection for me, I worshipped that pony. I still don’t really understand why—perhaps because he didn’t care, perhaps because I needed an ally or perhaps because I identified with him always getting it wrong and always being the outsider. Something clicked, and I loved him more because other people did not. He was tough, he didn’t care what anyone thought—mainly because he was a pony and he didn’t understand what they were saying—but he understood me and I think I understood him.

Only a few years ago I was asked to contribute a story about my first love for a book. Who or what had I first fallen head over heels in love with? Most people chose film stars, fictional characters or real-life boyfriends or girlfriends. For me, it was an obvious choice: I wrote about Frank.