10.

Ellie May

It would be too easy to think that snobbery is a trait restricted to human beings. Horses can also be arrogant, and thoroughbreds, bred for beauty and speed, tend to be the most self-admiring and superior of all. Then there are horses who are slightly less refined, whose bones are thicker and whose coat does not gleam like mahogany, however much it is brushed and polished. They look like grown-up ponies. These horses are referred to, even by people who would hesitate to define themselves as snobs, as “common.”

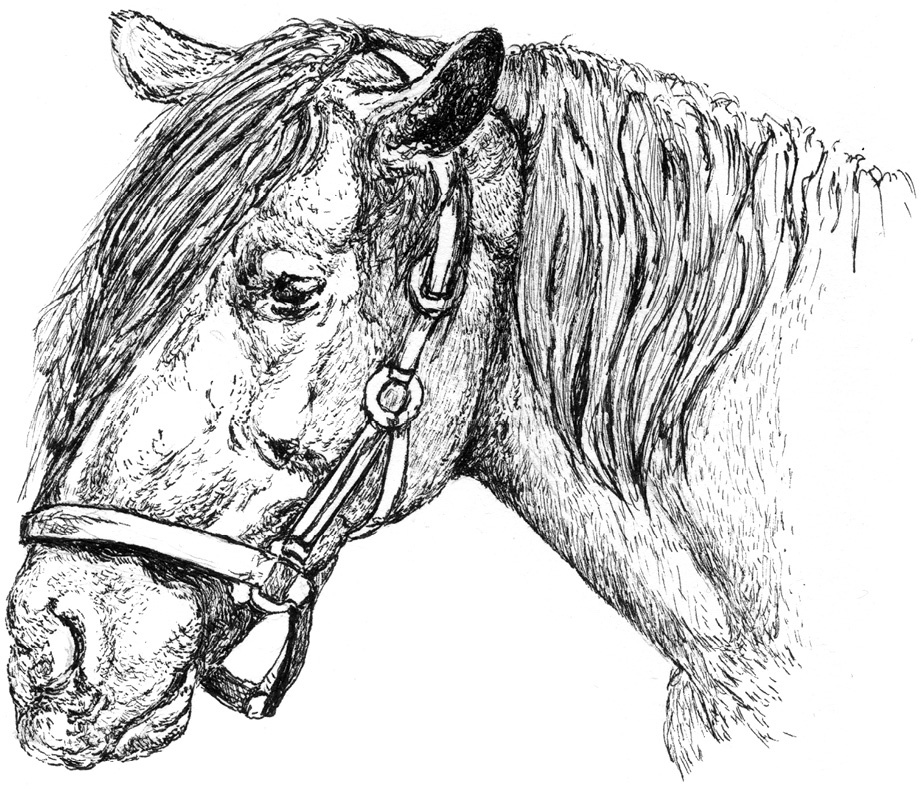

Ellie May was as common as you like. She had a deep girth, a thick-haired mane and tail, an enormous backside and a head that was pretty only to those who believe boxer dogs beautiful. Consequently, my mother adored her. Ellie May was Mum’s hunter and, a bit like my beloved Frank, her mouth had all the sensitivity of a block of concrete.

Ellie May may have had a bit of Irish Draft in her and a bit of cob. She was chunky and strong, with an ankle sock of white on her hind legs, a tiny line of white above her near-fore hoof and a small white star at the center of her head. She was officially “bay,” meaning she had a black mane and tail and a deep-brown body, neck, face and upper legs. She was fifteen hands three inches high and about seventeen hands round: to ride her, my mother’s legs went out sideways before they dropped downward.

Ellie May was no beauty, but she was safe and reliable. She would never fall, never refuse, and although she could pull she wasn’t fast enough to run away with her rider. She would plod along at the same pace, see a fence and shorten her stride accordingly, finding a place to put down her hooves where no space looked available. If two fences were five strides apart, Ellie May could fit in seven.

“She looks like a carthorse,” my father would say from his tall, handsome thoroughbred.

“Well,” said my mother at the opening meet of the Berks & Bucks Draghounds, “let’s just see who comes home in one piece, shall we?”

My father duly fell off three times as his fancy horse jammed on the brakes at the last minute, once sending him flying over a hedge on his own, while my mother took the sensible options and returned without a hiccup. She and Ellie May knew their limits and preferred to remain within them.

My mother was firmly of the belief that there is no point looking the part if you can’t do the job.

Unfortunately for me, Mum’s lack of interest in physical appearance meant that she had no truck with “fashion.” My growth spurt meant that I needed a new set of clothes and, while she relented enough to buy me blue suede ankle boots and purple-and-white-striped leg warmers, she stopped short at collarless shirts and oversized cashmere sweaters. She also refused to buy me white jeans because they were “impractical.” I managed to catch my father at a weak moment and persuaded him to give me a few old shirts and sweaters that had shrunk in the wash. With a pair of scissors and a bit of uneven sewing, the shirts were transformed into collarless ones, while the sweaters were stretched over the back of an armchair until they hung loose and shapeless, just how I wanted them.

~

My year in the Removes at Downe House had come to an end and we were allocated what would be our senior accommodation. A house was more than a place to live, it was also the team for which you would play, the group you would represent, and it would form the basis of the friendships you’d make. There were four houses at Downe House, and each had a different character. Tedworth was known as being quite academic, Aisholt was sporty, Holcombe was laid back and Ancren Gate (known as AG) had a reputation for being anarchic.

We were all moving from a tight-knit, tiny cluster of sixteen girls in Darwin to be divided up into random groups with the Hill House girls and then flung into one of those four houses, where we mixed with all of the girls up to the age of sixteen. It was potluck.

The Removes sat together as Mrs. Berwick called out the names and which house they had been assigned. There were cheers as girls who were friends discovered they would be in the same house for the next five years. These were nascent friendships that would become cemented into unbreakable bonds.

“Clare Balding,” announced Mrs. Berwick, “Ancren Gate.”

There were no cheers. If anything, there was a sigh. None of those already selected for AG particularly wanted me there, and all the friends I had made in Darwin and through lacrosse—Becks, Toe, Heidi, Char, Katherine, Cass and Shorty—were going into Aisholt or Tedworth.

The AG gang were confident, casual and detached. They seemed older than their years, and infinitely more sophisticated. I longed to be able to flick my hair from one side of my head to another, I dreamed of having a leather jacket, an older brother and a chalet in Switzerland. I so wanted to belong to this gang and yet I knew it was impossible—unless I changed.

I would have to impress them by being even cooler, even more daring, than they were. I would have to be the wildest child of the lot.

Some lessons in life, you learn the hard way.

AG was separated from the rest of the school. It was half a mile down a tarmac drive, surrounded by pine trees. We would cycle or walk up to the main school, our cloaks billowing out behind us like trainee witches’. It felt like an exclusive world, a closed environment where we could live and behave differently. Perhaps it was that degree of separation that encouraged those who felt they could write their own rules.

I was in a four-bed dorm with three other girls known as Bear, Pickle and Snorter (this was a girls’ school—we all had nicknames). They had all been in Hill House together and were firm friends. Bear was tall, with long, dark hair and a voice so deep you’d swear she’d been smoking since the day she was born. Pickle was thin as a rake and had scruffy blond hair permanently tied back into a scrunchie, with wisps carefully pulled out to fall around her face, which was drawn and worried. She bit her fingernails and had patches of dry skin on her arms, which she scratched when she was fretting. Snorter was always snorting. She would snort her food, snort out her words and snort when she was laughing. Her job was to laugh at everything Bear said, whether it was funny or not. She was a one-woman show reel of canned laughter.

As I unpacked my trunk on the first day of Michaelmas term 1982, I had a strange sense of foreboding. This was not going to end well.

Lessons were fine. I really loved learning. Having been a long way behind the others in subjects that hadn’t been covered at my primary school, particularly in French, Latin, math (I just didn’t get it), religious studies and chemistry, I was slowly catching up. My savior was English. I couldn’t get enough of reading, and I could use a book as a shield. I could disappear into my own little world, where the fact that I wasn’t included in the AG gang didn’t matter anymore.

I was fascinated by Greek and Roman myths. (I particularly noticed Golden Fleece winning the Derby that year, with Pat Eddery in the saddle, because of Jason and the Argonauts.) I enjoyed the impossible challenges thrown down to humans, the tragedy of vanity—Narcissus falling in love with his own reflection or Echo’s mournful cry haunting remote, rocky places. I loved the story of Pandora opening the box she had been told to leave closed. Out flew pestilence, war, disease and a myriad of evils. She shut the box and heard a knocking. The last thing remaining in the box was hope, without which none of us would be able to cope with life. I would remind myself of this tale when things went wrong—which they did.

The girls in my dorm largely ignored me. So I decided it was time to do something attention grabbing. We were on a school outing to Oxford, all of us wearing our skirts, blazers and long green cloaks. A small group, including me, took a detour into W. H. Smith.

“Time for some fun,” said Bear. “The one who comes out with the most free gear is the winner.”

Snorter snorted her approval. Pickle looked nervous but nodded enthusiastically.

“Come on, Balders,” Bear said to me. “Stop being such a square.”

So the gauntlet was laid down. In my head, I would be Hercules. I would fulfill the impossible task and become a hero in the process. My magic cloak would protect me. So I started to scan the shelves, accidently knocking off five bags of Opal Fruits. I bent down to pick them up, my cloak covering the ground beneath me. Four of the bags made it back onto the shelf, one went invisibly into my blazer pocket. Sherbet Dip Dabs were next, followed by strawberry Chewits and a packet of green-and-white-striped Pacer mints.

Underneath my cloak, my pockets were bulging. I could see Snorter and Pickle slipping smaller but more valuable items into their pockets—a fountain pen, ink cartridges, a Dennis the Menace ruler and even a cassette of Thriller. I could hear my heart thudding against my chest as I turned for the door. The rush of adrenaline made me feel faint.

Outwardly, I remained calm and cool. I even smiled at the assistant as I walked out, and said, “Thank you so much.”

We had agreed to meet up in a side street around the corner from Smith’s. I got there first and waited nervously for the other three to appear. Pickle came sprinting around the corner, her face flushed. She was giggling hysterically as she showed me some of the booty in her pockets.

“Wow, that was awesome. But so scary too. I sooo thought I was going to get caught.” Pickle was almost crying with relief.

Snorter appeared at a rapid rate a few minutes later. “Ohmygod, ohmygod,” she snorted. “The security bloke came in. With a walkie-talkie and everything. And Bear’s still in there. Ohmygod, ohmygod! What if she gets caught? What will we do?”

We looked at each other in shock, and then Pickle said, with tears in her eyes, “If my parents find out, I’m dead meat.”

She put her arms around Snorter and me. Together we formed a tight ring, chanting as one, “Bring back Bear! Bring back Bear!”

For the first time, I had been allowed into the group. Adversity—well, crime—had united us. Then came a deep, raspy voice.

“What the hell are you lot up to? You haven’t gone soft on me, have you?”

I looked through the sliver of a gap between Pickle and Snorter’s bodies to see the familiar swagger of our gang leader.

“The Bear!” we said in unison. “The Bear is back.”

We were all talking at the same time, all asking the same questions as fast as we could. None of it made any sense, but the sentiment was genuine. If you could smell relief, we stank of it.

We started to count the goods and to divide them equally between us. We were like the Four Musketeers or the Famous Five minus Timmy the dog, and I was high on love, laughter and adrenaline. We developed our own terms: “What did you buy?” covered goods you paid for, whereas “What did you get?” meant “What did you steal?”

Bear was the undisputed shoplifting queen. She came back from Newbury once wearing a brand-new leather jacket.

“Wow, how much did that cost?” I asked, still envious of anything that resembled a fashionable item of clothing.

“Nothing,” said Bear laconically. “Well, it would have cost over a hundred quid if I’d paid for it,” she said, running her right hand through her hair. “But I didn’t, did I? I tried it on, liked it and walked out with it on.”

I gasped. I was staggered at the daring. Pickle and Snorter were told of the Bear’s latest achievement, but it was strictly a dorm secret. No one outside those four beds was to know about it.

~

It is a Downe House tradition that, when it is someone’s birthday, a collection is made in a trash bin. The bin fills up with Hunkydory colored writing paper, purple Sailor pen cartridges, sweets, stickers, felt-tip pens and the like. If the birthday girl is really popular, the bin will overflow with goodies. If she is not, it will be a rather measly offering. The deal is that you only ask for gifts from your year and the years below; you never ask an older girl for presents.

As the youngest year in AG, we were constantly getting a knock on the door and the call of “Whacky-bee!” That’s what the birthday bin was called—a whacky-bee. Our dorm, obviously, had a huge collection of gifts, so we would happily pass on our stolen goods throughout the house. That way I could tell myself that, in fact, we were robbing from the rich to give to the poor.

This, of course, was a ludicrous defense. 1. No girl at Downe House was poor, and 2. Stealing from shops was not the same as robbing taxes back from draconian landowners to divide among the poor who paid them in the first place.

I had backed off the whole shoplifting season for a month or so, opting out of trips or insisting that I had to go to another shop without Bear or Pickle or Snorter, where I wouldn’t find anything I liked enough to steal.

“Oh, Balders, you just don’t get it,” said Pickle, chewing the sides of her already raw fingers. “You don’t have to like it or want it to nick it. You just do it for the thrill, you div.”

I was being edged out of the gang, I could feel the foundations of our dorm starting to tremble beneath my feet. I needed them. I needed to feel that I was part of the team.

So, one Saturday, after the three forty-minute lessons that took up the morning, we all hopped on our bicycles to head off to the Cold Ash village store, Foxgroves. It was about a mile down the road, and we were only allowed to go there on weekends. It was December, a week before the end of term, and we had decided to give each other a special Christmas whacky-bee—a bit like a stocking, only with stuff we actually liked.

I had saved up my pocket money so that I could buy some proper presents for the others. All our money was kept in a safe, and you had to be supervised by the housemistress if you took any of it out, signing in a book to confirm the amount.

I didn’t want to steal stuff, because this was a show of mutual respect and affection—you couldn’t just pass on “hot property.” I was in the far-right corner of the shop, inspecting the furry toys, when Snorter came up behind me.

“Look at these,” she whispered. She had in her hand three sets of tiny plastic mechanical feet. When you twisted the button on the side, like winding up a watch, they marched forward. They looked like brightly colored Doc Marten boots, and Snorter thought Bear and Pickle would love them.

“Cool,” I said, as this was the stock response.

“The thing is,” said Snorter, “I haven’t got any money and I haven’t got the right clothes on to, you know, ‘get’ them . . .”

Her voice trailed off and she looked at me with baleful eyes.

“I can buy them for you,” I said. I pulled out a ten-pound note from my pocket. “Look!”

“Don’t buy them, Balders. Christ, you div. Don’t buy them. Get them for me.” Her voice was urgent.

Snorter left the mechanical feet on the shelf beside me and walked to the cash register to chat to the shopkeeper. I could hear them laughing and realized that she was trying to distract Mr. Fell for me. So I took the three mechanical pairs of feet and slipped them into the enormous square pockets of my very square jacket.

I walked up to the cash register to pay for the other presents I had found, and Mr. Fell looked at me strangely.

“Is that all?” he said.

“Yes,” I smiled. “I think it is for now.”

“Are you sure?” He seemed to look straight into my soul as he asked.

I had been here before, so I knew that I could get away with it. We were invincible. Besides, they were only mechanical feet—it wasn’t a leather jacket.

“Thank you so much.” I smiled at him again as I paid and turned to go. “You have lovely things in here.”

If I had looked back, I would have seen the sadness in Mr. Fell’s face. I would have seen him shaking his head as he picked up the phone.

I gave Snorter the feet as soon as we got back to our dorm, and she hugged me.

“Cheers, Balders. You’re a rock. The others thought you’d lost your nerve, but I knew better.”

She patted me on the back. I sank into a beanbag to read my book, An Amateur Cracksman by E. W. Hornung. It was about a gentleman thief called Raffles. An hour or so later, there was a heavy knock on the door.

“Come in,” I shouted from my beanbag. Raffles was climbing over the rooftops with a diamond necklace in his dinner-jacket pocket. I kept reading. I looked up when I heard a clearing of the throat.

Mrs. Hamilton, the housemistress of Ancren Gate, was standing just inside the door. I had always thought she looked a bit like a rabbit, with buck teeth, fluffy hair and an edgy way about her. She seemed to be hopping from one foot to another.

“Clare, Miss Farr wants to see you.” She sounded terrified. “I really don’t know what it can be about on a Saturday but you are to go to her drawing room. Immediately.”

I closed my book. I really was calm, considering my little world was about to explode in the most unfortunate way. I patted the blanket on top of my bed as I left the room.

My legs carried me downstairs and on to my bicycle, but my brain had gone into neutral. I knew disaster awaited me, and I was flatlining. Don’t look into Medusa’s eyes, I thought. You will turn to stone.

Miss Farr was our headmistress. She was a jolly sort, round-faced, pale-blond hair scraped back into a sort of a do that none of us could work out. It wasn’t a bun, but it all folded in on itself and seemed magically to stay in place, except when she played lacrosse, when it would escape from the pins and stray down her head. Miss Farr had been an England lacrosse player, and she personally coached the first team.

I carefully opened the fragile wood and glass double doors that led to the headmistress’s drawing room and walked up the green-carpeted stairs. I knocked at Miss Farr’s door and sat to wait.

“Enter!” said the voice.

My hands were clammy. This didn’t feel good.

“Ah, Clare. Sit down, would you please?” Miss Farr was behind her desk, writing in a large leather-bound book.

I swallowed hard and sat. I looked out of her windows. There were so many of them. There was glass all down the south side of the room and beyond the windows was a stone-flagged balcony that connected the two sides of Aisholt, the house that was as near to the center of the school as possible. As I stared out of the window, I saw two of my year walk across the balcony. They looked in, and I quickly sank into the chair, hoping they wouldn’t see me.

Miss Farr looked up. She did not smile. Her eyes were kind, but I looked away, not wanting to hold her gaze.

“Now, Clare, you have a chance here. A chance I would like you to take. I had high hopes for you, very high hopes indeed.”

She sighed and her shoulders shuddered with the effort.

“I need you to tell me whether you were acting alone,” she said, and then stopped.

“Sorry?” I replied. “What do you mean?”

“There is a video camera at Foxgroves. They had it installed a few years ago, when we had an unfortunate incident. Mr. Fell informs me that you were in the shop this morning and that you left without paying for certain items.”

She paused, and I felt her gaze upon me. I was looking at my hands, which were gripped together in my lap. The rug, I remember, looked Persian.

“That,” continued Miss Farr, “is beyond dispute. It is captured on film. You will be suspended immediately. I am not going to expel you, although I certainly could. What I would like to know is this—were you acting alone or were you told to steal the items?”

“No,” I said immediately. “No, it was just me. No one else. It was all me.”

I thought this is what Hercules would do. He wouldn’t let his friends go down with him.

“I see,” said Miss Farr. “It just strikes me that you are not the strongest character at Ancren Gate and I fear you may have been led astray by other, more daring girls. Are you telling me that this is the first incident of its kind and that you are the only guilty party?”

“Yes. Yes, I am.”

They would really love me now. I would come back a hero.

“Right,” said Miss Farr. “Well, that is a shame. I have rung your mother already, and she is on her way here to collect you. You are suspended with immediate effect and, as we are only a week from the end of term, you will not be coming back to Downe House until January. By which time, young lady, I hope you will realize the error of your ways.

“I do not wish you to return to Ancren Gate,” she continued. “You will come here, to Aisholt, where I can keep an eye on you. I think you will find a more suitable set of friends here. Now go.”

Miss Farr picked up her pen and started writing again in her leather-bound book. She did not look up as I left the room. I felt as if I had been in a boxing match and, although bruised and beaten, I had upheld the honor of the noble sport of pugilism. I just needed someone to pass me a towel and raise my arm above my head.

I cycled back to AG and went up to our dorm. There was no sign of Pickle, Bear or Snorter. I started packing and, as I folded my clothes, a tear trickled down my cheek. I organized the three Christmas whacky-bees for my roommates and hid them in the cupboard where I knew they would eventually find them before the end of term. I left a note on top of the dressing table.

“Have a great Christmas. You guys are the best. Love, Balders. xxxx”

As I dragged my trunk down the stairs, I saw Bear appear in the hallway.

“Hey,” I said. “Looks like I got caught, but don’t worry, I didn’t say a word.”

Bear walked straight past me and went up the stairs, without even looking at me. So much for our special bond, our proper friendship. So much for loyalty. I was more hurt by this than anything that had happened that day.

I sat on my trunk at the bottom of that long tarmac road to AG hoping my mother would arrive before the rest of the house came back from watching and playing in matches. I heard the chugging of the Citroën Dyane before I saw it and saw my mother sitting behind the steering wheel, her hair in a ponytail. She was chewing her lip.

“I don’t know what the hell you’ve been up to,” she said, as she lifted one side of the trunk and we lugged it into the car and across the backseats, which were pushed down. “But you’ve got a bloody decent headmistress there. Why on earth she didn’t expel you, I do not know.

“You’d better have those bloody feet with you as well, because we’re taking them back.”

“I can’t, I don’t,” I stammered. “They’re not mine to take back, you see.”

I stopped. To say anything more would be to give the game away, so I fell back on another solution.

“I have this, though.” I pulled out the change that was left from my pocket money. It was nearly eight pounds.

“Well, why the hell didn’t you pay for the things you wanted if you had the money? Honestly, even now we’ve given you the money you’re still stealing. What is your problem?”

My mother slammed the door and walked to the driver’s side. She stopped at Foxgroves and pointed at the door. I got out, went inside to apologize to Mr. Fell and gave him the money for three pairs of mechanical feet. We drove home in a heavy fog of silence.

My father wanted to know exactly what had happened. He knew I was lying, and he told my mother so. It didn’t stop him from being cross, knowing that I had been part of a gang—he was livid—but it did help explain why I had got into such trouble. My father was a blow-up, blowout kind of man: one big eruption and then he would forget about it. Mum was a stewer, and her anger simmered on for weeks, months, even years.

Mum erased any benefit I may have thought I was getting by being on holiday early by banning me from riding. I wasn’t even allowed down to the stud to see Ellie May or Hattie. I offered to help muck out and groom, but Mum wouldn’t have it. She made me work every day in the dining room, as if I was still at school.

I felt as if the oxygen had been turned off at the valve. I was plodding through each day with no joy, no comfort. Please let me off the hook before Christmas Day, I repeated to myself. Please.

Andrew came back from prep school, and the glow around him shone brighter than ever. Grandma came over for tea to hear his stories and to ask him what he wanted for Christmas. She only looked at me once, and said: “I think you can do without a Christmas present this year, don’t you?”

I told Andrew what had happened to me—he was shocked but defended me whenever he thought I was being unfairly blamed for something else. He was my little brother, and he would fight for me.

Once Andrew was home, it was harder for my mother to keep me locked in the dining room all day, so I was partially freed and allowed to ride. Hattie was having the first part of the winter off so, if I wanted to ride something that jumped, it would have to be Ellie May. In my ridiculous Downe House way, I had been a bit of a snob about the heavy-footed, bushy-tailed Ellie May. She was not as fine as Hattie and I had felt faintly embarrassed as I rode through the yard on her.

I decided to take Ellie over on to the farm to jump the drag-hunt fences, just to give myself a thrill. I was still feeling full of self-loathing and my head was dull, as if I was recovering from a concussion. As I turned down Long Meadow, Ellie took it upon herself to wake me up.

She broke into a canter and then picked up the pace, her stride not altering in length but multiplying at a faster rate. I had her on a line toward the first of the fences, a heavy log over red barrels. As we came toward it, I started to lose my nerve and tried to steer her around it, but Ellie wouldn’t hear of it. She ignored my tugging on the reins and attempts to pull her sideways, and set herself like a large ship on a Channel crossing.

I could only sit tight and try to go with her. We sailed over the barrels and, as the tempo increased, we came to the Tiger Trap, then the tractor tires and the row of straw bales. There were three sizes to this last set—nine jumps in all, the biggest of which were about three feet six. Sizable enough for an eleven-year-old riding an unfamiliar horse. I attempted to angle Ellie toward the smaller option, but it was pretty clear by now that she was in charge, and I was too tired to fight. I sat into the saddle, squeezed my legs round her belly and felt her soar off the ground. Once, twice, three times she flew over the big straw bales, which had a thick black telegraph pole on top of them.

It was the first time I had ever jumped the biggest bales at the end of Long Meadow. Ellie May pulled herself up to a trot after she had jumped the last one, then to a walk, puffing at the effort of it all. We had covered a mile in distance, jumped nine large cross-country fences, and all of it had been at her insistence. She turned her head to the left, looking straight at me with her left eye, and then nodded, as if to say, “That’ll teach you, you stuck-up little rich girl.”

As we walked down the chalk path that ran below Smith’s Bushes back toward the farm, I thought about where I had gone wrong so far at Downe House. I had been sucked into valuing appearance and possessions above all else. I had lost my respect for honesty, for kindness and for hard work. Ellie May was the proof I needed that I should not judge anyone on looks alone.