15.

Mailman

I think I’m having a nervous breakdown,” I said.

“Don’t be ridiculous. People like us do not have nervous breakdowns.” My grandmother was standing in our kitchen. “Only people with too much time on their hands do that.”

Apparently, “people like us” didn’t have depression either.

“Deeply selfish,” said my grandmother.

We weren’t obese (“lack of self-control”) or anorexic (ditto). We didn’t get pregnant out of wedlock and we didn’t “do” divorce. When one of my relatives suddenly left his wife for another woman, Grandma said, “If he wanted to have sex, I really don’t see why he had to make such a fuss about it. Just have an affair and keep quiet. But this—so public and, frankly, so cheap.”

Grandma used to walk every day, her walking stick in hand, striding out across the fields with her greedy Labrador, Chico, or her whippets—first Dawn, and then the ill-fated Dusk. She was a dog person. I always got the impression that she thought cats rather common—which is why it was so out of character that she had two of them: Tommy and Katie.

She always called Tommy by his name, and he followed her around, but Katie she called Titty-Wee.

“It’s the ugliest name I can think of,” she said. “And she is an ugly cat. Useless as well.”

Andrew and I had never had much to do with the cats, apart from carrying out a practical experiment to prove whether or not they always landed on their feet. This involved rolling each one up in a blanket and dropping it over the banister from the top of the stairs. Yes, was the answer, they did land on their feet. We did not get the chance to repeat the experiment—not because Grandma discovered us (she may have approved) but because both cats disappeared whenever we walked into the house.

The tension I was feeling was because my “A” levels were imminent.

“Pressure?” Grandma scoffed. “You have no idea what pressure is.”

I expected my grandmother to launch into a list of her most grievous worries: inheritance tax, the problems of finding a good butler these days and the difficulty of cleaning raw silk. Instead, she said, “I was in the WRNS during the war, you know. I loved it. We drove armored vehicles, deciphered codes and learned how to fire a gun. I even took an electrician’s course. I’m a whizz with a bunch of wires.”

I had never imagined my grandmother doing anything except issuing orders to other people who “did” things. I knew she was intelligent—she did the crossword every day and she played Scrabble—but I hadn’t realized she could be practical as well.

“It was a funny time, the war,” she said. “The world sort of turned upside down for a while. It was better when the men came back.”

Now here’s a thing I have never understood. My grandmother was denied a trainer’s license because of a misogynistic law, she was one of the first female members of the Jockey Club, she was a steward at various top racecourses and a director of Newbury racecourse, she managed a farm and a stud, she was one of the most independent and self-sufficient women I have ever met—and yet she did not believe in equal rights for women. Nor did anyone in my family.

“You can’t do that.”

“Why on earth not?”

“Well, you’re a girl, for starters.”

My Uncle Toby, whom I adored, used to say, “Women ain’t people.” My father and brother would laugh along. My mother treated it as a joke. I never laughed, because I was appalled.

“Are you turning into a feminist?” my mother would ask, raising her left eyebrow. She rolled the distasteful word around her tongue and spat it out.

I was reading Mary Wollstonecraft at the time, so I was full of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. She wrote it in 1792, and I was overflowing with righteous indignation that we had achieved so little in the two centuries since.

“I would hope I am a feminist, yes,” I said.

I went on strike, refusing to load the dishwasher or help set the table unless Dad and Andrew did so as well. Mum never asked them to, so why should I do it?

“Because you’re a girl,” said my brother, refusing to budge from the window bench on the inside of the table, where it was nearly impossible to get out anyway. “It’s your job.”

I walked out, in a huff, and heard him saying, “I just don’t know why she gets so wound up about it. It’s not as if women can’t vote.”

My father has only just stopped putting his coffee mug, still half full, in the kitchen sink and started putting it in the dishwasher, where it belongs. He is seventy-three years old and has never done the supermarket shopping. He is not an idiot, but he has found it suits him much better to pretend he can’t work the stove or the dishwasher or the washing machine, and my mother has let him get away with it.

“You will get along a lot better in life if you learn to massage a man’s ego,” my mother told me. “Even if you have a good idea, it’s much better to let a man think it’s his idea.”

I know what she was trying to do, but I just couldn’t see the point of massaging anyone’s ego. If they were good at what they did, I’d say so, but if they weren’t, why would I lie, just to make a man feel superior?

I vowed that I would not pretend that I was ditzy or uninspired, I would not back down from doing the things I wanted to do and I would not wait for a man to define my position in the world. That did not mean I did not like men, but I could not deal with men who did not recognize a woman’s value beyond the size of her breasts.

I tried to say all of that without bursting into tears, which would have rather ruined the whole effect. My mother raised that dangerous left eyebrow again and said, “Well, I’m sure you feel better now you’ve got all that off your chest.”

~

I had been to a meeting with the careers officer at Downe House, a short, round woman called Mrs. Trumble. She told me I was being overambitious in trying for law at Cambridge.

“Honestly,” she drawled, in the most acerbically rich accent you can imagine, “I cannot think what it is that makes you think you are capable of Oxbridge. It is misplaced confidence, I am afraid. The other universities will take it out on you, mark my words.”

In the short term, Mrs. Trumble was proved right. The offer from Cambridge was two “A’s and a “B.” I got an “A” and two “C’s. Not good enough for my first choice, nor for my second- and third-choice universities. I left the results slip on the kitchen table and ran down to the stud. I tacked up Stuart and disappeared for over two hours. We galloped, we jumped, we stopped to look at the view, and I told him everything as I let the tears flow. By the time I got back, I had dealt with my own disappointment. What was harder to deal with was the disappointment of my parents.

My father could not understand why his old college, Christ’s, that had taken him with no “A” levels at all, on the basis of his ability to catch a book flung at him by the senior tutor, would not take me. Nor would Bristol, nor would Exeter.

“I didn’t get the grades,” I explained for the third time. “It’s really simple. They made me an offer and I couldn’t match it.”

“But I don’t understand,” he kept saying, over and over again.

Many years later, I discovered that part of his anger derived from the knowledge that he had made a rather large donation to the Christ’s College fund. He insists that he did not try to buy me into Cambridge but I was not convinced and could happily have drowned him in the horses’ swimming pool.

~

“How much do you weigh?” My father was speaking as he read the Sporting Life. I was sitting at the breakfast table, buttering a piece of toast.

“I’ve no idea.” I hadn’t weighed myself since the spring, when I was riding in point-to-points. “I’ve been a bit busy taking exams to worry about it.”

“Well, run upstairs and use my scales. I need to know exactly how much you weigh.”

He had bought some new scales with weights along the top which you moved to position for stones and pounds. They were so accurate, they could tell you if you had put on or lost ounces. I moved the weights along to what I hoped I was, and then moved them along a bit more, when I realized I was a bit heavier than I had thought.

“Ten stone five,” I said, as I came back into the kitchen.

“Well, no more of that then.” Dad pointed at the toast and butter. “You need to be nine stone ten in ten days’ time. You’re riding in a flat race at Salisbury, so you’d better get sweating.”

He asked me my weight that evening, the next morning and again the next evening. He lent me his sweat suit and showed me how to work the sauna.

“Don’t let it get too hot,” he said. “If you do, you’ll just burn. Keep splashing the water on the coals here. That’ll make it steam, and it’ll help you sweat more. Then lie down on the bed for a while with lots of towels round you, and you’ll sweat a bit more. You can lose six or seven pounds in a day if you do it right.”

What he meant was he could lose six or seven pounds in a day. I never could. Two or three, yes, but never more than that. I rode out three horses every morning, went running in the afternoon in the sweat suit or cycled for miles on the exercise bike, wearing the sweat suit and listening to INXS on my Walkman. Then I would sit in the sauna for forty minutes. I tried to read books there, but the glue in the spines melted and the pages fell out, so I turned to magazines and would emerge from the sauna with print all over my hands and face.

I stood on the scales at least six times a day and, if I wasn’t moving the weights to the left, I felt worthless. As for eating and drinking: half a cup of tea when I woke up, before I rode out First Lot; a slice of melon at breakfast with half a glass of orange juice and slurp of coffee; a salad for lunch; and a ready-made Lean Cuisine meal for supper. I was so tired from the running and the sweating that I was good for nothing in the evening, and would collapse into bed by nine o’clock, hoping beyond hope that I would wake up two pounds lighter than I had gone to sleep.

It was hard work, and it was horribly boring, because all I could talk about was how many pounds I had lost or needed to lose and whether chicken and orange or beef stroganoff was my favorite flavor Lean Cuisine. I was obsessed. I trimmed my fingernails, shaved my legs, cut my hair, all to save the odd ounce. I loved being able to fit into slimmer clothes, and I felt more confident about my body, but the dieting was not about looking good, it was all about numbers. How much did I weigh? Dad needed to know exactly.

The answer was that I weighed nine stone thirteen pounds. I nearly fainted if I stood up too fast, and my mouth was dry with dehydration. I was going to have to put up overweight, which would be broadcast humiliatingly on the loudspeaker system, but I could do no more. If I had been born a light-boned waiflike thing, none of this would have been such a heartbreaking effort.

~

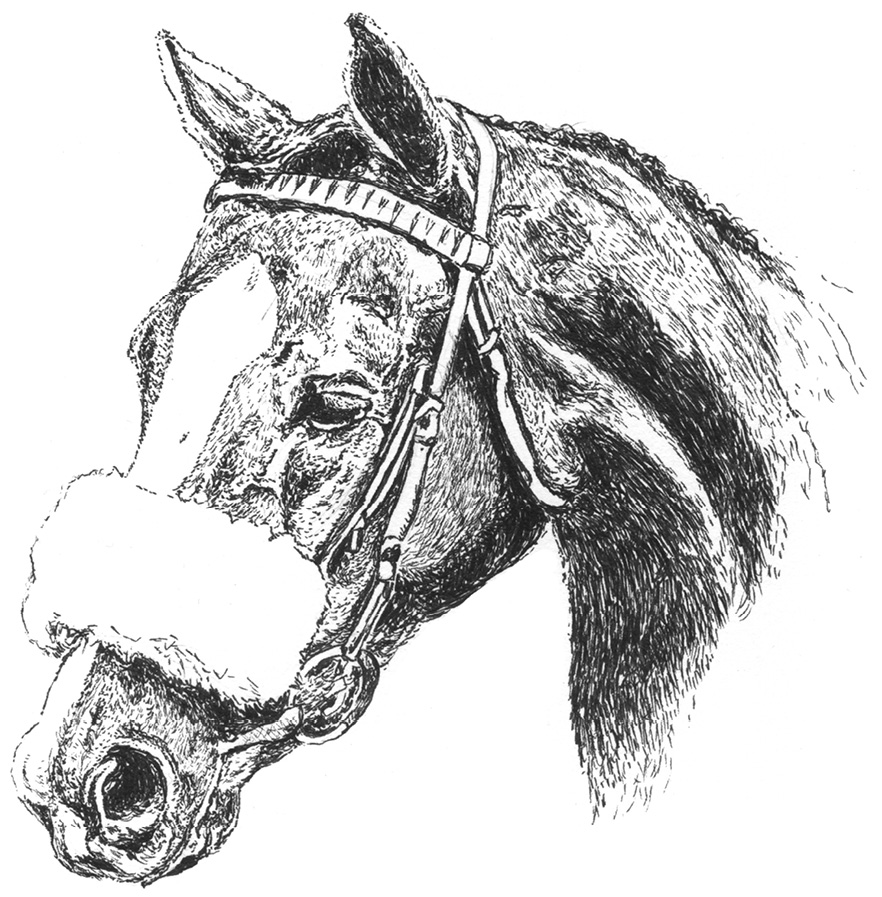

On July 9, 1988, I rode in a mixed amateur race at Salisbury on Mailman, the tall, lean, liver chestnut horse with a white blaze down the front of his face. He was nine years old now, and set in his ways. At home, he was a difficult ride and pulled so hard that only Bill Palmer could ride him. Dad had suggested I ride work on him, just once on the Downs, so that I could get a feel for him. He ran away with me when we were doing our steady first canter and scooted past all the other horses in the string.

I could hear Dad swearing at me, and I swore back because I was grouchy. I was doing the best I could, but my strength had gone. We set off over a mile for a piece of work that was meant to be at three-quarter pace for six furlongs, quickening up to full racing pace for the final two furlongs. I struggled to keep Mailman at three-quarter pace, so we ended up going flat out for six furlongs and steady for the last two, by which time he was exhausted. Dad said I was useless, but he still insisted that I should ride in the race itself.

I was terrified. What if I couldn’t hold Mailman and he took off with me? There were fifteen other runners, and I’d look a fool. It would be shown in betting shops around the country. I may not have been getting paid for riding him, but there was plenty at stake.

Salisbury is a right-handed course in the shape of a number 9 with the loop on the left of the tail. The mile-and-a-quarter start is at the top of the tail, and you are fairly quickly into a tight, right-handed bend. I walked the course carefully to see if it was slippery on the inside, or if there were ridges to avoid. The straight was long, more than five furlongs, so I figured there was plenty of time to make up ground if I needed to. That’s if I could settle Mailman behind the other runners.

There were twenty-three runners for the Brooke Bond Tea Cup Handicap Stakes for Amateur Riders. I had weighed out at ten stone two, including a saddle and the lightest girths Spider could find. I blocked my ears as the announcement was made on the public-address system that Miss C. Balding would be carrying three pounds overweight. I had had my hair cut even shorter to try to save a few ounces, but it wasn’t enough.

It was my first time jumping out of starting stalls and I had watched videos of professional jockeys doing it to try to work out how to avoid bouncing up and down in the saddle as if you’re on a space hopper. I decided that the best way was to lean forward, grip the neck strap tightly and use it to pull myself up into “race position” as the stalls opened. Professionals do not do this (most of them don’t use neck straps), but for a thick-thighed amateur whose bottom had a gravitational force worthy of its own square law, it was a sensible option.

When the stalls open, there is a fractional delay before any of the horses react. In that moment, the world seems to stop and then suddenly bursts into life again. The field set off at a fearsome gallop. There is never any lack of pace in an amateur race, as someone is nearly always getting run away with. In this case, I was grateful it wasn’t me. Mailman settled into his stride in the middle of the field, and I waited for things to happen.

What I know now is that, in most flat races, you do not have the luxury of “waiting for things to happen.” You make them happen. Jane Allison, who was riding a three-year-old trained by Paul Cole, made her move four furlongs from home and shot clear of the field. With apologies to all those who may have had money on Mailman, I have to confess I did not even notice. I was merrily galloping along, saying, “Good boy,” in Mailman’s ear, thrilled that he had settled so well and thinking about how long the straight was.

With three furlongs to go, I could hear shouts and the crack of whips around me and, with two furlongs to go, I figured I’d better try to do something about it. Jane was ten lengths ahead, and the rest of the runners had nothing left to give, so Mailman and I set off in lone pursuit. I could see the orange colors of Storada getting closer and closer. There was a roar from the grandstand that I’d never heard before as punters who had backed Mailman or Storada shouted their chosen horse home. When you’re standing in that crowd, it’s like listening to an orchestra reaching the end of a crescendo. When you’re riding, the wind rushing past your ears means that the music stops and starts.

I tried to move in rhythm with Mailman, urging him to quicken. I didn’t use my whip because, despite my father’s careful instruction, I did not feel confident at all about taking one hand off the reins for fear of losing my balance. I may have tapped him down the shoulder, but no more than that. We were making ground with every stride, reaching Storada’s quarters then drawing level as the winning post came closer.

I looked sideways as we flashed past the post. A stride after it, Mailman was in front. On the line, where it counted, he was a head behind.

“Bloody hell, that was close,” said Jane, as she puffed out her cheeks in relief.

The result of the photo finish was announced as we pulled up.

“First, number 6, Storada. Second, number 22, Mailman.”

I should have been disappointed. I should have been frustrated at my lack of urgency, but I was too busy being elated. It was such a thrill, a total rush of adrenaline to have survived in that big a field, and for a nine-year-old gelding to have run that well against a three-year-old colt. I was beaming as Jo, who looked after Mailman, led him back into the winner’s enclosure. Spider had given him a pat and said, “Well done.” Everyone seemed really pleased.

Except the punter who shouted, “A few less pies next time, Clare!”

And my father.

“You should have bloody won” were his first words. “What the hell were you doing? It’s a race, not a bloody Pony Club event. There are no rosettes for finishing second.”

I kept smiling, slid down from the saddle, patted Mailman and kissed him on the nose. My mother walked with me back into the weighing room, where I stood on the scales to check that my weight was the same as before the race. Much as I would have loved the experience to have miraculously turned me into a featherweight jockey, the scales read exactly the same.

Dad fumed pretty much the whole way home and made me watch the video again and again while he told me exactly where I should have made my move and what I needed to do to galvanize even more acceleration from my horse. He made me sit on the arm of the sofa, as Andrew and I used to do for the Grand National, and practice using my whip.

“You don’t need to use it often,” he explained, “but the noise will make a horse run faster. You make sure you hit him in the right place, up here.”

He took my arm and showed me how to raise the stick so that I would hit a horse on the top of the quarters, where there is plenty of protection, rather than down the flank, where the skin is thin. I was used to carrying a whip for everyday riding, and for eventing. When you’re trying to control half a ton of horse, it helps if you’ve got something that can get their attention and remind them of your presence, but I had rarely had cause to raise the whip in anger. Dad was trying to show me how to use it effectively, judiciously and tactically—never in anger, and always in rhythm with the movement of the horse.

I had spent so much of my life resenting the hold horse racing had over the rest of my family that I had deliberately avoided getting too involved. I recognized the good horses and enjoyed the big races but, beyond that, my knowledge and my concern was limited. Overnight, I was interested in racing.

Now I had actually ridden in a race and felt a response from a racehorse, I was intrigued. I rode out each morning with the rest of the yard, rode work on Wednesdays and Saturdays and, steadily, I got the hang of it. I concentrated hard on my diet, ran every day in a sweat suit or went on the exercise bike and weighed myself constantly. The markers on the scales started to go to the left.

Three weeks after that first ride at Salisbury, Mailman and I teamed up again, this time at Ayr. It was the PG Tips Tea Cup Handicap Stakes for Amateur Riders. There were eight runners on a miserable, gray, soggy day on the west coast of Scotland. Mrs. McDougald’s colors were pale gray and pink. In the rain, they stuck to my skin and became see-through. This was my major concern as I cantered down to the start, having weighed out at ten stone exactly. I had decided to ride in a much smaller saddle so that I could make the weight. Mum was in charge this day, as my father had runners down south, and she raised that damned eyebrow as she collected the saddle from the weighing room.

“Are you sure you’ll be all right in this?” She lifted the saddle between her thumb and forefinger. It was barely bigger than her hand.

“I’ll be fine,” I snapped. “Just stop fussing.”

Mailman, on the strength of his good run at Salisbury, was second favorite. I walked into the paddock to join my mother and Andrew, who was on hand as a would-be assistant trainer. In theory, he was meant to give me my instructions, but all he said was “Wow, those colors are totally see-through.”

Mum gave me a leg-up in the paddock, and I felt for the stirrups. They were much shorter than I wanted, so I leaned down to adjust them. There were no more holes in the leathers—they were at maximum length. I had never ridden in this saddle before and hadn’t thought to check the stirrup leathers until now. It was too late.

Of course I said nothing to my mother. I cantered down to the start looking like Lester Piggott, and just hoped that my legs would hold out for the mile and a quarter on the way back. I think my father had told me to ride a similar race to Salisbury—try to settle Mailman in the middle of the field but make my move sooner and be aware of what the other runners were doing.

“Remember, it’s a bloody race!” he said.

It’s hard sometimes to do exactly what you’re told to do, especially if the stalls open and you find yourself in front. So I just let Mailman gallop. He wasn’t out of control, he was setting an even tempo, and I didn’t have an awful lot of choice about it. I figured he’d run in around fifty races, so he knew what he was doing.

I could feel the rain lashing at my face, and I couldn’t hear anything. As we approached the final furlong, still no cracking of whips, no hooves, no shouting. I let my reins out a few inches, Mailman stretched his head forward and we stuck close to the rail as we covered that last 220 yards. With a hundred yards to go, I suddenly heard something.

Dad had told me not, under any circumstances, to look around: just keep looking forward, ride for the line and keep going right past the post. So all I had was this sense of impending doom. A whistling noise, a roaring, a blast of breathing that was intensifying with every stride.

“Grrr. Go-on, go-on!”

It was a man’s voice. I could feel a horse’s head at Mailman’s tail, then at his quarters, then level with his girth. I kept pushing, but I didn’t pick up my stick. I was frightened that, if I did, I might fall off. My legs had gone to jelly. I looked up and saw the winning post and, as we passed it, I glanced sideways. We had held on by a neck from Simon Whitaker on the favorite.

I had ridden my first winner on only my second ride. Simon shouted, “Well done,” as we tried to pull up, and all I was thinking was: Don’t fall off, don’t fall off.

I clamped my hands down on Mailman’s withers and used them for support, as I hoped that he would naturally slow down to a trot. He did, and he turned himself around and started cantering gently back to the entrance to the paddock. That horse could have done it all on his own if he had to. I had merely been a passenger, and I knew it.

Mum was waiting in the number one spot under a large umbrella, her face lit up by a huge grin. I slid off and, as my feet touched the ground, my legs gave way. I tried to cover it up, but my mother is not a fool. I assume that people thought she was hugging me rather than holding me up.

“Those stirrups were much too short,” she whispered. “Don’t make that mistake again.”

I only rode in four more races in 1988, but three of them were sponsored by Brooke Bond, because my father had suddenly realized that I had earned enough points to be in contention for the Brooke Bond Oxo Amateur Riders’ Championship, a series of ten races for amateur riders. The winner would get a brand-new Austin Rover Mini. I had not yet taken my driving test.

The final race of the Brooke Bond series was at Haydock on October 1. No one had ridden more than one qualifying winner, so the points were wide open. I had earned five points for winning at Ayr and three for finishing second at Salisbury, so was the joint leader. The Princess Royal had won one of the qualifying races, as had Jane Allison and the leading female amateur Elaine Bronson. Any one of ten riders could win the Mini outright if they finished in the first four.

If none of them did (and not all were riding in the race), I would be the joint winner with Yvonne Haynes. If she finished in the first four and I did not, she would win the Mini on her own.

There were sixteen women and four men making up the field of twenty and, for the only time in the year, the ladies’ changing room at Haydock Park was full. Loudest of the female riders was Sharron Murgatroyd, who three years later would suffer a fall at the final hurdle of a race at Bangor that would deny her the use of her limbs. Since the age of thirty-one, Sharron has been a tetraplegic and has written fabulous prose and poetry about her life then and now.

Murgy, as we called her, was taking the mickey.

“You can’t win the car, Balding!” she shouted. “You can’t even drive. How are you going to get it home? In the back of Daddy’s horsebox?”

Sharron was never unkind, but she made it clear that I was among the fortunate ones. I did not have to ring unsympathetic trainers begging for rides or travel the length and breadth of the country on no travel expenses riding no-hopers in egg and spoon races. I had my father’s support; I had a silver spoon sticking out of my rich little mouth.

Elaine Bronson, another chirpy, chatty, hardworking rider, joined in.

“Give us those ’ands!” she said, grabbing my hands and turning them over in hers. “Look at ’em. Soft as a baby’s bottom. You’ve never done a hard day’s work in yer life, ’ave you?”

“Ah,” I said, “but look at that line there. That says I’ll be lucky and, if you can’t be hardworking, you might as well be lucky.”

Elaine and Murgy laughed, and we walked out to the paddock together, past the sparkling red Mini on display just outside the winner’s enclosure.

“Lovely, innit?” said Elaine, stroking the hood of the car. “Don’t touch it, Clare, you’re not allowed. If you haven’t got a driver’s license, you can’t touch it.”

She cackled with laughter and headed off to meet her trainer, while I looked for my parents in the paddock. For once, my weight was not an issue. Waterlow Park, the horse I was riding, was near the top of the weights in the handicap, so I could have a big saddle with lead weights in it. I had made the most of not having to diet, and my breeches were a little tighter than they should have been.

There are plenty of sports in which you are reliant on the achievements of others to decide your own fate, but the key in each one is to try to control the things within your grasp. The only way I could do that was to do my damnedest to finish in the first four. Dad told me to keep it really simple, to stay out of trouble and, on soft ground, to make sure we had enough left in the tank for Waterlow Park to finish well.

It didn’t sound that “simple” to me, but we did our best. I was in the first four until the last furlong. Murgy came past me to finish second, and then Geraldine Rees, who a few years before had become the first woman to complete the Grand National. I had memorized all the colors of the riders who could overtake me in the standings, and couldn’t see any of them ahead of me. If I could just hang on to fourth place, I would win the Mini.

Waterlow Park was starting to get tired, the soft ground sapping his energy. I shouted encouragement at him, slapped him down the neck with my whip and tried my best to move a little bit in rhythm. I could feel another horse coming to our quarters, so I got desperate. I picked up my whip in my right hand and tried to hit him on top of his quarters, just as my father had shown me.

I missed. Honest to God, I did the equivalent of an air shot, and nearly fell off. That was the first and last time I ever tried to hit a horse behind the saddle. I rode seventeen winners in total over my short, sharp riding career, and I did not hit a single one of them. I couldn’t do it. I got overtaken for fourth place and crossed the line in fifth, half a length ahead of Elaine Bronson. Crucially, Yvonne Haynes finished down the field.

My father was busy working out the points situation as I came back into the area of the paddock where the “also rans” are unsaddled. If he had noticed my failed attempt at a backhand crack with the whip, he didn’t say so.

“I don’t know how they’ll do this,” he said. “You’ve both finished on eight points. If they do it on count back, they’ll have to go down to fifth places, so today was crucial, but if they do it on overall rides, she’s had more than you.”

In the event, Brooke Bond decided to award two cars. Yvonne Haynes was presented with the keys to the Mini that was at Haydock that day, and she drove it home. Ten days later, I passed my driving test and a bright-red Mini (number plate F661 MTF) was presented to me by a man with a mustache on the forecourt of the Austin Rover dealership in Newbury. Unfortunately, in the photo taken for the Newbury Weekly News, you can’t see any Austin Rover signs—but you can see, clearly in the background, a sign for Magnet kitchens.

I had learned to drive in my mother’s Volkswagen Golf and had taken my driving test in it as well. The gearshift for that moved to the left for first and second gears, straight up and down for third and fourth. Driving the Mini home from Newbury, I could not work out why, every time I shifted it up for third, it went back into first gear. I settled for second gear and drove it all the way home in that. I had no idea what “running in the engine” meant.

Between riding in races and winning the Mini, I retook my history “A” level and got it up to an A grade. In terms of finding a place at a university, I now had decent enough grades with which to go to war.