17.

Waterlow Park

Amateur races do not usually elicit much newspaper coverage. A round-up in the Racing Post and the Sporting Life, perhaps a mention in Horse & Hound, yes; amateur races never make the national dailies. Never, that is, unless there is a member of the Royal Family involved.

And, crucially:

It was all a bit of a hoo-ha, you see. These things happen in races—a bit of bumping here, a bit of boring there: general spirited discussion. You can’t legislate for what might occur around the tight turns of, say, Beverley, if a horse happens to jump a path and takes himself to the inside rail and someone else is bumped in the process.

Well, you can legislate, and that is what the Rules of Racing are for but, sometimes, shit happens. That’s what I’d have said to the Princess Royal, if she’d still been speaking to me. She wasn’t, though. Not after the Contrac Computer Supplies Ladies’ Handicap, a race over a mile and a half, worth £2,262 to the winner. Worth nothing to the winning jockey, obviously, apart from a rather nice crystal vase.

It was hardly the Diamond Race at Ascot, which was the highlight of the ladies’ season—the winner got a diamond necklace—but if you’re a competitive beast, you want to win every race you enter, not just the glamorous ones. Her Royal Highness the Princess Royal rode at the Olympic Games of 1976 in Montreal, won a gold medal at the European Championships of 1971 at Burghley and two silver medals in Luhmühlen in 1975. The Princess Royal is a highly competent horsewoman, of that there is no doubt.

As an amateur rider, her experience was less extensive. She had ridden many times over jumps, had had a few winners, and on the flat had won the Diamond Race in 1987. She had even ridden a winner for my father on a horse called Insular, who was bred by the Queen.

Wherever the Princess Royal rode, the ladies’ changing rooms would receive a hasty makeover, which was incredibly useful for the rest of us. She changed alongside us and did not expect any special treatment. I found this rather confusing, given that I had been brought up to curtsy to the Queen and follow official protocol.

When I curtsyed to the Princess Royal in the changing room at Beverley and called her Your Royal Highness, she said, “Don’t be ridiculous.”

She was standing in her underwear at the time, so perhaps a curtsy was inappropriate.

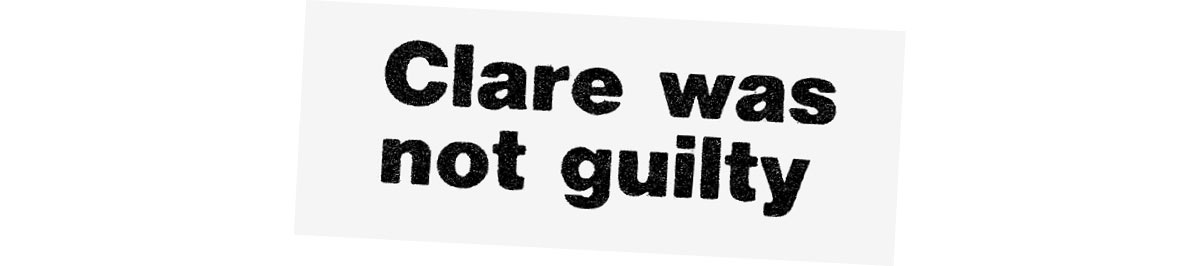

The Princess Royal was riding a horse called Tender Type. He had finished out of the money in his three starts that season and was therefore dropping down the handicap. Waterlow Park, my mount, was having a terrific season. He’d had seven runs by the beginning of August, had won three of them and finished second or third in the others. I had ridden him to victory at Goodwood in June, and he was a lovely ride, even at home. He was a big, strong chestnut with a slightly off-center blaze of white down the front of his head. He was quiet and gentle, an all-around gent. He was the perfect ride for an apprentice or an amateur.

My mother had driven me to Beverley. As we neared the course, I felt the familiar twinge in my stomach. It wasn’t stomach cramps due to laxatives; it was nerves. I rubbed my hands together—they were clammy; and my jaw was tense. I asked Mum if I could put on the lucky songs I needed to listen to before I got to the racecourse and, fairly soon, as we bombed along the A614, Peter Gabriel’s “Big Time” was blasting out of the cassette player.

My mother joined in for the chorus, and we were screaming, “Big time, so much larger than life!” as a Range Rover sped past us.

“That was Princess Anne,” said my mother. “Make sure you keep out of her way today.”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” I sang back. “Big time, my house is getting bigger. Big time, my eyes are getting bigger. And my moow-ow-outh.”

I had read the form on all the other runners, I had thought about the race and had memorized the tactics my father wanted me to use. Once the music stopped, I was on an adrenaline wave that lasted for the next couple of hours. I was in a heightened state of nerves, talking ten to the dozen, taking in details and remembering facts that I would never normally digest. If I could have taken exams when my brain was whirring like this, I’d have got straight “A”s.

I loved this stage, and I got more and more nervous before the race, running to the toilet more and more often until the point that we were called out to the paddock.

“Jockeys!” a voice shouted into the changing room, and we filed out into the weighing room and down the steps into the paddock.

My mouth would go dry and I wouldn’t say much, but as soon as I was legged into the saddle, a switch would flick. It was as if it was all happening to someone else. My heart rate slowed, my nerves disappeared and I relaxed. During the race itself, I always felt as if I had all the time in the world. If the pace was too slow, I went on. If the field was going too fast, I waited at the back of it. Gaps seemed to appear when I needed them and, if they didn’t, I would yell at someone in front to “give me some room.”

The same thing happens now when I do live television or radio. I get nervous in the build-up, have to listen to some loud music in my headphones and then, as soon as I see the red light and know we’re live, I relax. From the start of the program, I feel in control, and the more that goes wrong, the more I enjoy it. I am never happier than when the running order has been thrown out of the window, because I reckon that’s what I’m there for. Anyone can present a program that is going well; it’s what you do when it’s going tits up that makes the difference.

In this particular race, there were ten runners. Elaine Bronson, who had become a firm friend, Amanda Harwood and Tracey Bailey (who was married to the trainer Kim Bailey) were all in the line-up. The Princess Royal was wearing colors similar to mine—hers were chocolate and turquoise, mine turquoise and brown.

“I hope the gamblers don’t get us mixed up,” I said as we circled at the start.

“Unlikely,” she replied.

I swallowed hard, even though there was no saliva to swallow. I was out of my depth.

The mile-and-a-half start at Beverley is right in front of the stands, and the crowd was leaning over the rails, shouting encouragement to us.

“Come on, Cler!” I heard a voice say. “Don’t mess it up. My cash is riding on your backside.”

Waterlow Park had never been that quick to jump out of the stalls. He dawdled, stumbled slightly and broke slower than the horses all around us. We were last of the field as we passed the winning post the first time. At least, I thought we were last. As we turned away from the grandstand, he saw a path made by the pedestrians crossing to the inner section of the racecourse. He jumped it on an angle, took himself to the inside rail and made up about four lengths in the process.

It was at that point that I realized I had not been last out of the stalls. One horse had reared as the gates opened and had been almost ten lengths behind us all. By the time we got to that first bend, he had made up the ground and was just behind me, on my inside as Waterlow Park jumped the path.

“What the hell are you doing? Watch out! Watch out!”

There were other words that were shouted. Naughty words that I need not repeat here.

Oh God, I thought. I’ve carved someone up. At least it wasn’t the Princess Royal. She’d never swear like that.

I heard more chatter behind me, but I was focused on the horses ahead of me, on where the gaps might appear and what I needed to do to achieve the best possible finish. There was that man who had staked his cash on my backside. I needed to do my best for him.

We swung into the straight, and the field fanned across the course, as they often do in amateur races. It was like the parting of the Red Sea, and I let Waterlow Park accelerate. He didn’t find as much as I expected and could not pull clear. I kept pushing and could hear the cracks of whips all around. There were three of us in a line and then I could feel another horse closing fast. As we flashed past the line, I thought I might just have won, but I wasn’t sure.

A stride past the line, the turquoise and chocolate colors of Tender Type were ahead. The Princess Royal had made up a huge amount of ground in the straight and had finished faster, but none of us were sure who had been in front on the line.

I took my time pulling up, partly to allow for the result of the photo finish to be called, and partly because I was scared. I’m not sure if I was frightened of having lost or of having won. Either way, it spelled trouble.

My mother was, to quote Procol Harum, a whiter shade of pale as she greeted me in the paddock.

“Do you know what you’ve done?” she said, in an urgent whisper.

“Yes! I think I’ve won.” I attempted to win her over with a hesitant smile.

“Not that!” she replied. “The first bend. The very first bend—what the hell were you doing? You nearly brought down Princess Anne. I have just had the Duke jabbing his finger at my forehead telling me you are effing dangerous and shouldn’t be allowed loose on a racecourse in any effing country in the world.”

The Duke was David Nicholson, the Princess Royal’s racing guardian. He was a champion jumps trainer, a man who had won Gold Cups at Cheltenham and King George’s at Kempton, a man who chewed weak people up and spat them out for breakfast, moving on to idiots for lunch and strong people for supper. He had masterminded the racing career of the Princess Royal, supervising her riding out in the morning and her rides on the racecourse, even if they were for other trainers.

I could imagine him in full flow, accosting my mother (whom he’d known all his life) and taking out his fury on her. Now I could see him giving Princess Anne the full force of his opinion. She had been robbed. Robbed and mugged by a highwayman. Me.

The PA made a noise. The judge had been studying the black-and-white freeze frame of the finish for well over five minutes.

“Here is the result of the photo finish,” the voice intoned. I looked down at my saddle cloth to double-check my number. It was one.

“First”—the PA announcer milked the dramatic pause as if he were presenting a game show—“number one.”

A cheer went up from those gamblers who had backed Waterlow Park. At least they were on my side. To celebrate too much would have seemed churlish, so I patted him on the neck and practiced my “humble winner” face.

“There is a dead heat for second,” the voice continued, “between number two and number six. Fourth is number seven.”

The distances were a short-head, dead heat and another short-head back to fourth. You could have thrown a blanket over all four of us but, right on the line, Waterlow Park had stuck his neck out, and his nose, with its sheepskin noseband, had passed the post just in front of Tender Type, who finished best of all to dead-heat for second.

I slid to the ground and took my time taking off the saddle. I really, really did not want to go into that changing room.

I weighed in and went out to the winner’s enclosure to receive my trophy. On the way back into the weighing room, I noticed the door to the stewards’ room was ajar and they were looking at the film of the race. I poked my head around and made history as the only winning jockey who has ever said the following: “Could I just check, are you having a stewards’ inquiry?” Plenty of beaten jockeys have asked, but if you’re declared the winner it’s usually a good idea to thank your lucky stars and move on.

“We’re not,” said the stewards’ secretary, “but if you’d like to see the film, you’re welcome.”

So I saw how far Tender Type had been left at the start—no wonder I hadn’t realized he could have been behind me. I saw Waterlow Park jump the path and angle himself toward the inside. Tender Type was knocked sideways, causing the Princess Royal to snatch up.

“We can see clearly from this angle,” said the stewards’ secretary, a military man, with an upright back and clipped tones, pointing to the screen with a cane, “that you did not cause the interference intentionally, Miss Balding. Frankly, we feel that you could have done nothing about it and that it happened too early on to make any difference.”

Armed with my defense, I steeled myself for reentry into the war zone. I opened the door to the ladies’ changing room quietly and heard different voices saying, “She’s always doing it” . . . “Thinks she can get away with anything.”

Elaine Bronson later told me that she thought the whole thing was hysterical and that she was winding up the Princess Royal for fun. To be fair to the others, I had come on the scene a bit fast and was riding more winners than a second-season amateur should do. I was the new threat.

The Princess Royal was standing with her back to me. As she spun around, my world stopped turning. I swallowed and stood there, not knowing what to say. I looked her in the eye, mainly because she was not dressed and I was embarrassed to look anywhere else.

“So,” she said, “are they having a stewards’ inquiry?”

“No,” I replied. “I did ask but, no, they’re not. They say that it happened too early on to make any difference.”

“Really?” The air had grown chilly. “Nothing happens too early on to make the difference of a short-head.”

“I’m sorry, Ma’am. I really am,” I said. That’s where I should have stopped. I really could have walked on into the room and quietly gotten changed. But I am me and I don’t always know when it’s best to stop talking: “Most genuinely sorry . . . but I was not about to pull up in the straight and let you win.”

In the film version of this moment, I will be Spartacus and my fellow amateur riders will one by one start clapping. In the real version, they sucked in their breath. This was a dangerous move.

The Princess Royal fixed me with a steely glare.

“Well, maybe you should have done,” she said, and turned back to continue dressing. If I had had a weak bladder, I might have wet myself.

The Sun reporter wrote: “The princess had a face like thunder when returning to the weighing room. And she summoned an especially withering glance for an intrepid scribbler who attempted a brief interview.”

There was plenty of talk of me asking for a royal pardon, and the general theme of the articles was “Upstart amateur, daughter of the royal trainer, carves up the Queen’s daughter on the first bend and then beats her in a photo finish.”

On BBC television, Julian Wilson introduced the video footage from Beverley and asked Jimmy Lindley for his opinion.

“Clare Balding has committed the cardinal sin of race riding,” said the former professional jockey. “She has shown absolutely no regard for the horse behind her. You can’t do that, you simply can’t. I am surprised she was not disqualified.”

That was my first inside lesson in how the media works. A story will be told from the angle that best suits those telling it.

For the rest of that year, the Princess Royal and I rode in the odd race together and successfully avoided getting too close—either on the course or off it. Two years later, in 1991, we were back at Beverley riding in a one-mile race with only seven runners. The Princess Royal was on a horse called Croft Valley, trained by Richard Whitaker, who had also trained Tender Type. I was on my beloved Knock Knock.

The Duke saw my mother as soon as he arrived at the racecourse and walked toward her. Although tempted to run away, she stood her ground and let him say his piece.

“I’ve realized that I was a bit harsh,” he said. “I’ve watched your daughter a lot since that race—and I may have been wrong about her. She’s clearly competent. I’m sorry.”

Mum smiled. “That’s all right, but please don’t jab your finger at me again. It’s rude.”

“I won’t, if she stays out of the way this time.”

Croft Valley won by a neck from Knock Knock and, as we were pulling up, I spoke to the Princess Royal for the first time in two years.

“Well done, Ma’am,” I said. “Happy now?”

I know. I know. I should have just shut up after the “Well done,” but I couldn’t help it. The brat in me breaks out sometimes. I thought it was a funny line but, for a joke to work, you need a receptive audience.

~

Waterlow Park beating Princess Anne at Beverley had contributed to a fabulous 1989 season during which I rode six winners from nineteen starts at a strike rate of more than 30 percent. I was leading the amateur championship and the Lanson-sponsored competition to be leading Lady Rider. We came to the last race of the lot at Folkestone in October. I had flown back from Paris to ride, and my fitness as well as my weight had suffered from the baguette diet. Despite riding out in Chantilly, I felt woefully out of practice.

The only rider who could pass my points total was Elaine Bronson. She continued to tease me for being soft, rich and, now, continental.

“Jetting in from Paris, how flash is that? Still not working for a living then?”

The last time we had ridden together, Elaine had offered me CDs and Puffa jackets from the trunk of her car, at a “great discount.”

“Honest, Clare,” she promised me, “you won’t find a better deal.”

She made me laugh but, my God, she was ruthless. She had to win this race. Nothing less would do. If she won, it didn’t matter where I finished—she would win the title. If anyone finished in front of her, I would hold on to my points lead and be crowned champion.

Elaine worked for a trainer called David Wilson. He was a renowned form expert and always appeared at the races with a massive book in his hand, in which he noted down all the past runs of various horses, with comments and his ratings. He was a clever trainer, placing his horses well and often pulling off a betting coup. His talent was in targeting a horse at a specific race and making sure it had a handicap mark that gave it a chance of winning. Kovalevskia was the four-year-old filly he had selected for Elaine to ride in this final, championship-deciding race. She had run poorly in her previous three starts, all over farther than a mile and a half, so had dropped down the handicap. Now running at her preferred distance again, she had a definite chance but, according to the betting, my chance on Straight Gold was better.

“See you on the other side,” Elaine said as we loaded into the stalls.

Sharron Murgatroyd was riding in the race as well.

“Play nicely, girls,” she shouted. “And may the best woman win.”

Elaine made all the running. She was five lengths clear and stretching away as we turned into the straight at Folkestone, and as I knew Straight Gold wasn’t traveling well enough to catch her, I shouted, “Someone go after her. Please!”

Straight Gold started to run on, but it was all too late. Kovalevskia won by fifteen lengths. It was a rout.

I cantered up beside Elaine and patted her on the back.

“Well done,” I said. “Amazing result.”

“She’s a flying machine, this filly,” she said. “I knew I’d beat you, but I never expected it to be so easy.”

She winked at me and grinned. “Work—it does pay off, you know.”

Part of me was pleased for her. I liked her and, when I saw David Wilson hugging her and lifting her off the ground in the winner’s enclosure, I figured that they must have had a major bet as well. Kovalevskia had been backed in from 14–1 to 9–1. There was a lot more riding on the result for them than there had been for me.

It still hurt, though. I may have been the leading amateur, but I went there thinking I could be the champion lady rider as well, and instead I had to stand there watching someone else winning their weight in champagne, someone else being declared the best in the country. The top sportsmen and -women will tell you that it is moments like this they hold on to. They want to remember the pain of losing to spur them on in the dark, cold hours of lonely training. They are masochists, the lot of them. I really don’t want to remember it at all.

I knew I would cope, but I couldn’t bear the disappointment of others. I didn’t want to look at my father as I walked into second place. He had always maintained second was for losers. Now, he surprised me.

“Never mind,” he said. “You did everything you could and you’ve had a wonderful year. We gave it our best shot, and we’ll make sure we win both titles next year.”

With that, he kissed me on the cheek and patted my shoulder.

“Don’t forget to weigh in,” he said, as I tried to pretend that I wasn’t crying.

As we were driving home, Dad reminded me that I had at least won something. He gave me a box and a card. In the box was a butterfly brooch and on the card it said:

To the Champion Amateur

(and so nearly the lady’s too)

With lots of love from

A very proud Dad