1.

Candy

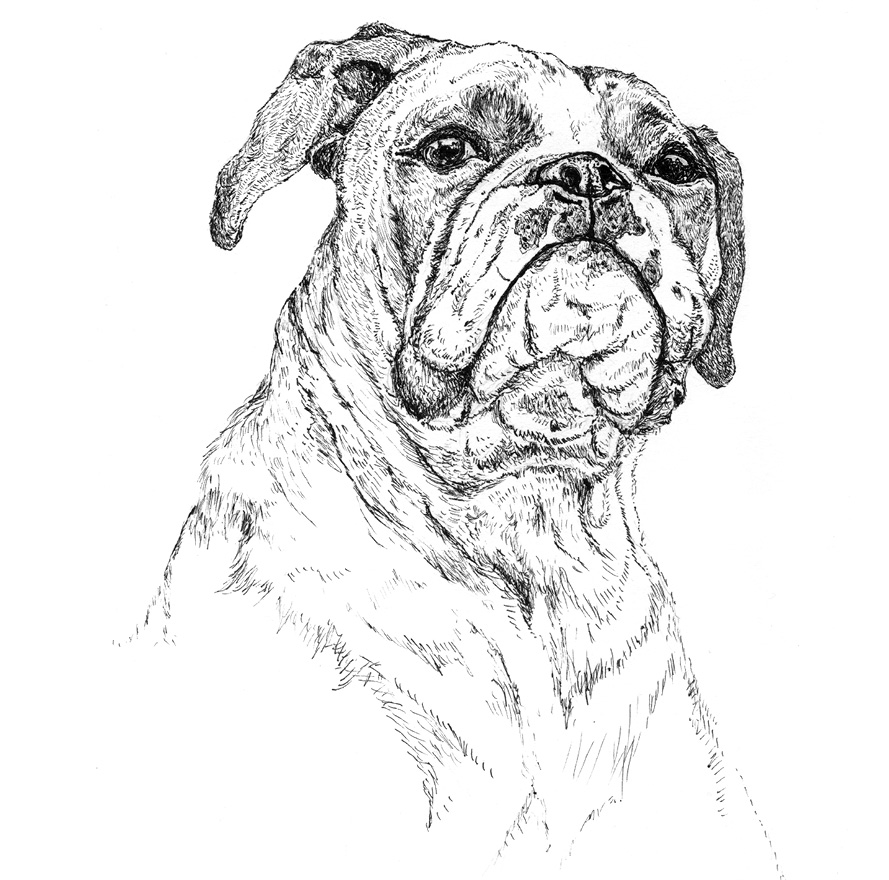

The first face I can remember seeing was Candy’s. She was my protector and my companion, my nanny and my friend. A strong, snuffling, steady presence.

I looked into her big brown eyes, pushed my pudgy fingers into her cavernous wrinkles and smelled her stale breath. It was an all-in sensory experience. I was home.

I pulled her ears, lifted back her lip to examine her tiny teeth and gripped her rolls of fat, but she never snapped, never growled, never even gave me a warning glare. Candy was a saint and she knew her role in life. She was put on earth to guard me and she would, to the end of her days.

Candy was my mother’s boxer, and the pecking order was clear—in terms of affection and attention, Candy came first and anyone else, new baby included, came second. Candy loved my mother without question and my mother needed that from someone, even if it was “only” a dog.

Candy was what they call a red-and-white boxer: a deep-chestnut color in her body, with a white chest, white around her neck and across her face. Her eyes sagged, her titties swung low and loose and her girth was wider than was strictly desirable. But as far as my mother and I were concerned, Ursula Andress could move aside—she had nothing on Candy.

When she was excited, Candy’s whole body showed it. The move started in her stub of a tail and proceeded to her hips, which would rotate from side to side, making it virtually impossible for her to walk. Her body shook with delight and her lips drew back in an unmistakable grin. Most of the time she was rather matronly and sensible, but when she was happy, she was delirious.

I adored her and she responded with an immediate, unquestioning sense of duty. She would lie by my side, move if I moved and allow herself to be a living, breathing baby-walker as I used her to climb to my feet, wobbling on my plump, short legs as she pulled me gently forward. When the strain got too much and I collapsed on to a diaper-cushioned backside, she would sit and wait for me to get going again. She didn’t much like other people coming near me, particularly men, warning them off with a withering glare.

Candy seemed to be the only one who was pleased to get to know me. The day that I first came back from the hospital, Mum put the basket down on the floor and left me there. Bertie, the aloof lurcher with pretensions to grandeur, had a quick sniff, cocked his leg on the side of the basket and demonstrated exactly what he thought of it all. He stuck his head in the air and walked off, never to give me a second glance.

Candy, on the other hand, planted herself next to me, and there she stayed. It was a comfort, now I think about it, that she was so protective. You see, I was a disappointment from the minute I popped out, and there wasn’t a thing I could do about it.

“Oh,” said Grandma, a woman routinely described as “formidable,” “it’s a girl. Never mind, you’ll just have to keep trying.”

Robust and six feet tall, my grandmother was a daunting presence. Her hair, neither long nor short, was “done” once a week by a woman called Wendy, who came to the house. Grandma wore no makeup, believing it to be “for tarts and prostitutes.” Her favored formal uniform for race days was a raw-silk dress and matching coat, tailor-made to accommodate her unfeasibly large bosom, and nonpatterned, because patterns accentuated the mountains. Sensible court shoes, a spacious handbag to hold wallet, glasses, diary and binoculars, the outfit topped off with a matching beret or—in the summer—a silk turban-style hat.

During the week Grandma would wear a calf-length skirt with a plain-colored polo neck or cardigan. She never wore trousers. Once upon a time she had been a competent horsewoman, but she gave up riding when the sidesaddle was discarded. She refused to countenance the idea of riding “astride” and did not approve of women wearing jodhpurs.

She didn’t much approve of women, full stop, especially women with “ideas above their station.”

Grandma came from a family of statesmen, prime ministers and patriarchs. Her grandfather was the 17th Earl of Derby, but, as the daughter of his daughter, she would inherit little more than a nice collection of jewelry and a strong sense of entitlement. Her childhood had been split between a town house in London, an estate at Knowsley on the outskirts of Liverpool (now Knowsley Safari Park) and a villa in the south of France. Her mother, Lady Victoria Stanley, had died in a hunting accident when Grandma was just seven years old. Perhaps that accounted for her lack of maternal instinct.

None of the children got much attention, but the boys at least had the advantage of registering a presence. For the one girl in the lineup, early life was a losing battle.

My mother had had one staunch ally during her childhood years: her father. Captain Peter Hastings could trace his lineage back to the House of Plantagenet, which included Henry V and Richard the Lionheart. Deep in that family tree was also a mysterious link to Robin Hood. As far as my family is concerned, Robin Hood is not a fictional figure. He was Robert, Earl of Huntingdon.

He existed, and he still does. And not just in Hollywood films but in the middle names of my uncles. Every one of them is Robin Hood, and Uncle Willie—William Edward Robin Hood—is the 17th and current Earl of Huntingdon. It is a title that is worth very little in material value—there is no stately home and no land to go with it—but it has a certain historical magic, I suppose.

Uncle Willie, my mother and their two brothers did not see much of their parents. Nanny took care of the children’s everyday needs and a nursery maid was ever present. They got under the feet of Mrs. Paddy, the cook, and mimicked Stampy, their butler. The household bristled with staff.

The children ate, played and slept in the east wing of the house. They were presented to their parents in the drawing room of the main house at exactly six o’clock every evening: William, Emma, Simon and John, in that order. All present and correct. All sent to bed.

My grandfather is the reason that we lived at Park House Stables in Kingsclere, a village on the Hampshire/Berkshire border. His uncle was a brewery magnate called Sir William Bass. Sir William had no children and was concerned that the Bass name was threatened with extinction. So he asked my grandfather if he would consider adopting Bass into his own name.

Grandma was appalled.

“I will not have any part of that common beer name,” she said. “You can if you wish, but let it be your business.”

My grandfather duly changed his name by deed poll to Captain Peter Hastings-Bass, and all of his children’s surnames became Hastings-Bass. My grandmother steadfastly remained Mrs. Priscilla Hastings. Most people called her Mrs. Hastings. A few close friends called her Pris. Two naughty nephews dropped the “r” and got away with it, but woe betide anyone who called her “Prissy.”

“I am not Prissy. Not to anyone!”

In return for the adoption of the name, my grandfather inherited the Bass family fortune on Sir William’s death. In 1953 he used it to buy Park House Stables and the surrounding fifteen hundred acres on the southern outskirts of Kingsclere. It had the benefit of downland turf on Cannon Heath Down that had never in its history seen the blade of a plow. It was deep, lush, springy grass—perfect for gallops. There were just over fifty stables, onsite accommodation for the employees and a house big enough for an expanding family and domestic staff.

It was a magnificent house. The short drive, between two Lebanon cedar trees planted in the middle of perfectly maintained lawns, led up to a front door that stood twelve feet high and seven feet across. A stone vestibule protected it, with ivy-enlaced columns on either side. The north-facing wall of the house was covered with a mature Virginia creeper, while the south side boasted sweet-smelling hydrangea.

The house had huge sash windows that filled the rooms with light. The only room that was dark was the kitchen, where the cook and her army of helpers baked, steamed, boiled and roasted slightly below ground level. The kitchen separated the adult side of the house from the children’s quarters.

When guests were welcomed through that front door by Stampy, the butler, his heels would click together on the black and white marble floor. My grandparents shared the main bedroom, with windows to the south and west, their views across the adjacent farmland—also part of the estate—to Watership Down and beyond it to Beacon Hill. Sir William Bass would have been satisfied with the acquisition afforded by the addition of his surname.

My grandfather would only enjoy his new surroundings for a few years. A persistent cough that had been with him for ages worsened, and his skin turned a shade of yellowy gray. As illness ravaged his body, he had to make plans that would last beyond his lifetime.

He employed a twenty-four-year-old American-born assistant trainer in whom he saw something special. He was a good amateur rider, had a rugby-union blue from Cambridge, played cricket and polo. He was handsome, with jet-black hair parted to the side, full lips, dark-brown eyes and clear, fresh skin, marred only by a livid red scar across his left cheek.

He had an extraordinary way with horses and, importantly, he was not intimidated by my grandmother. He had no family money, which might be construed as an advantage, as it made him less likely to leave. The only negative was that he had a reputation for being a bit of a ladies’ man. Grandpa was confident he would grow out of that.

His name was Ian Balding. Six months after he arrived at Park House Stables, my grandfather died of cancer at the age of forty-three. It was 1964, the year of the Tokyo Olympics. My mother was just fifteen. Nanny passed on the news of their father’s death and the instruction from their mother that none of the children were to cry in public.

The grief belonged to Grandma and to her alone.

In terms of the business, it was two years before the Jockey Club would allow women to hold a trainer’s license. They were banned on the grounds that female trainers might see semi-naked jockeys in the weighing room—and who knows what might have happened if that came to pass! Might they be overcome with desire? Faint from the shock?

Grandma had to allow a man to take over as the trainer at Park House, so she allowed Ian Balding to take on the license. She remained on hand to help with the owners, many of whom were personal friends, and she had her views on which races the horses should run in, but the management of the business, of the staff, and the day-to-day training of the horses was the responsibility of my father.

Grandma and my father ate dinner together every night. They had breakfast together every morning. He rode out with the racehorses, a flat cap on his head, a tweed sports jacket worn over his dark-beige breeches. Grandma walked or drove with her whippet and her Labrador to stand by his side, binoculars in her hands. They commented to each other on how each horse was moving, how each rider was coping and whether a certain race at Ascot, Newbury or Goodwood might suit. Ian Balding charmed the sensible pants off the widow Hastings. He made her laugh.

Ian introduced her to a colorful array of girlfriends in miniskirts, tight tops and big sunglasses, their hair piled up high. None of them met with the approval of Mrs. Hastings. He worked hard, he trained winners, played cricket with the boys, tennis with the sporty American owners and often drove my mother back to school, much to the delight of her teenage friends. Ian was the only one she could talk to about her father and how much she missed him. She was only fifteen and needed someone with whom to share her fears, her problems and news of school, to test her on her French and talk to about her domineering mother. Ian became that confidant and, best of all, when he dropped her off, her friends would gather around and giggle excitedly as the Cary Grant lookalike took her suitcase out of the trunk.

My mother was bright. She excelled in English and history and was an A-grade student. She was advised by her careers teacher at school to apply to Cambridge University. Her eldest brother, William, was already there, at Trinity College. Her younger brothers, Simon and John, would eventually follow. When it came to Emma, however, there was no encouragement.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” said Grandma. “I will not have a bluestocking for a daughter.”

There was no point in arguing. The sixties may have been in full swing, but my mother was locked in a Jane Austen novel where women learned to play the piano, to sew and, if it was strictly necessary, to cook. They could be witty, pretty and well read but God forbid they should be “clever” or have opinions of their own.

Ian suggested that Emma go to America to visit his family. By coincidence, his little sister Gail had been at prep school with Emma and they had been firm friends. It was the first time my mother had been abroad. Family holidays had always been taken at Bognor Regis, in a rented house within walking distance of the pebbly beach. Crucially, it was not far for Grandma to leave the children and join her friends at Goodwood racecourse. The children came to dread Boring Bognor.

So my mother flew to America, the land of the free—free at least from her mother. When she came back, armed with her own declaration of independence, she went to London to find a job. She grew in confidence, had her own income from work as a secretary and was enjoying being able to make her own decisions, but when she went home it was back to square one. A contemptuous “What on earth do you think you look like?” from her mother would send her scurrying back to her room to change her clothes to something more conservative. Progress was constantly and consistently blocked.

Ian Balding, meanwhile, was fitting in just fine. He looked good in a dinner jacket and even better in sports gear. He hadn’t been in the army so had none of the constraints of officer syndrome and didn’t live in tweed or yellow cords. He was different from any man any of them knew—there was a hint of danger about him, yet he looked like a Boy Scout.

He was far removed from and much more fun than any of the men my mother met in London. She watched the way he dealt with her mother and envied him. He had such an easy manner. She rode with him one morning and, after the racehorses had finished their work, Ian called out, “Come on, Ems, we’re going back this way.”

He headed toward the fence line and popped his horse over a jump about three feet high onto the side of the Downs. Emma followed. They galloped along together, jumping everything in their path—hedges, ditches, post and rail fences. She felt exhilarated—galloping on a tightrope of fear and fun.

Many women had stayed in the guest room of Park House and were certainly worth creeping down the corridor for, but none had quite made Ian feel the way he did that morning on the Downs. As if overnight, Emma had grown up. He had never really looked at her before, not like that.

Three months later, he asked Grandma for permission to marry her only daughter.

“Really? Well, that’s very kind of you,” she said.

My father went to telephone his mother in America while Grandma called Emma in to see her.

“I understand you’re going to marry Ian. You’re a lucky girl.”

“Oh,” said my mother, “am I? He hasn’t asked me.”

He never did actually ask her but, clearly, it had been decided. When he rang America to pass on the good news to his own mother, Eleanor Hoagland Balding said, “So which one did you choose, the mother or the daughter?”

The wedding was organized by my grandmother. My mother was allowed to invite ten friends. She was twenty, my father thirty. A number of his ex-girlfriends (the ones whose names he could remember and whose addresses he had logged) came to St. Mary’s Church in Kingsclere to see the great charmer finally tie the knot.

With no father of the bride to call upon, Grandma decided that it would be appropriate for Emma’s eldest brother, William, to give her away. My mother was horribly nervous. She had not really had time to think this through. Ian made her heart skip a beat but she wasn’t at all sure that she was ready for this. She dreaded the sight of all those women from her fiancé’s past, in their miniskirts and trendy hats, their sunglasses and platform shoes. It felt a bit like the ride on the Downs—dangerous, with the threat of a fall right around the corner.

Her brother William stood with her outside the church door. She looked to him for comfort as he took her hand to lead her down the aisle. The best he could offer was “Your hands are sweaty.”

So Ian and Emma, my parents, were married in the summer of 1969. They honeymooned in Cornwall, at a house belonging to a friend of Dad’s. They couldn’t be away for long because the flat season was in full swing and my father was busy. They stayed for four nights and then they were back to the hectic life of Kingsclere and the glare of my grandmother.

My father gave my mother a horse called Milo as a wedding present. It was a re-gift, really, as Dad had been given him and continued to ride him. By 1970, he’d clearly forgotten that he had gifted him to my mother at all, as he rode him in his own colors and listed himself as “owner” for the whole point-to-point season.

My mother’s life ran to the clock of her new husband. His work was important and all-consuming. The horses were divided into two “lots” of around thirty horses each. One was exercised before breakfast, the other after. My father got up before six, rode Milo out with First Lot and then went to Park House for breakfast with my grandmother, his assistant trainer and Geoff Lewis, the stable jockey. Then he rode out a different horse with Second Lot and went to the office to plan the entries, speak to the owners, pay the bills and sign the checks for the staff wages.

There was racing from Monday to Saturday. On Sundays, he played cricket in the summer and rugby in the winter. Or my mother drove the horse trailer to Tweseldown or Larkhill or Hackwood Park so that my father could ride Milo in a point-to-point.

His life was frantic, but my mother was lonely. She needed company. So she trawled the ads in the Horse & Hound, the Telegraph and the Sporting Life. Eventually, the Newbury Weekly News came up trumps:

Boxer Puppies for Sale

3 BITCHES, 2 DOGS

Already weaned. Ready for new home.

Phone Paul on 0703 556218

Mum and her younger brother Simon drove down to Southampton to see the litter of puppies. Paul opened the door wearing a tight white blouse, an A-line skirt, a silk scarf tied in a bow around his neck and full makeup.

“Come in, come in,” he said as he ushered them through the door. “Now, sit down, the both of you. My, what a handsome couple you make. Cup of tea?”

Uncle Simon blustered and flustered, “We’re not, we’re not . . . It’s not like that. She’s my sister,” not sure where to look.

Paul shimmied into the kitchen to flick on the kettle.

“So, my lovelies, what do you know about boxers? Do you realize how much work they take, how much exercise they need, how they will take over your life?”

He made tea, and for half an hour he told them every detail about the behavior of boxers. He grilled my mother about the house, where the dog would sleep, how often it would be exercised and what sort of lifestyle it was entering into. My mother was tested further on her suitability to be a dog owner than she had been to be a wife. Forced to think about it more deeply, she knew that this was what she wanted.

When finally allowed to see the litter of puppies, she was captivated. One of the red-and-white bitches was playing with her brothers when my mother knelt down beside the pen. Paul and Uncle Simon stood back to let the bonding process begin. The puppy looked up at my mother and wiggled her hips. Mum leaned down to pick her up, and the puppy seemed to smile. She licked my mother’s face and then pressed her velvet head into the soft part of my mother’s neck, just below her jawline.

My mother smiled and a tear formed at the corner of her eye.

“Hello, you,” she whispered. “Where have you been?”

Uncle Simon uttered his first words in an hour. “We’d like to take that one, please. If it’s not an imposition. If we can, that is.”

Paul had watched my mother and understood. She had been a bit stranded, floating on a raft not of her own making.

“Of course. She’s weaned, she’s had her injections and she’s good to go.”

Candy sat by Uncle Simon’s feet in the passenger seat of the car. He was wearing open-toed sandals, which was how he realized, as they passed Winchester, that she had peed on his foot. It was the only thing she ever did wrong.

Boxers are such fun to be around. Forever playful, fiercely loyal and always affectionate, they will demand a full part in family life. Mum said that if we grew up thinking that boxers were beautiful, then the whole world would be a beautiful place. She was right.

~

I arrived about six months after Candy, in January 1971. My father was not present at the birth. It was not the done thing.

I spotted early on that the dogs got lots of attention so worked out that it would be best to be a dog. I crawled to drink from the water bowl—I mean, who doesn’t do that? I stopped short of sharing their food, because I was a fussy eater.

During my early years, Candy was queen of our castle and she took her responsibilities seriously. When a photographer came to take an official black and white photo of “the new baby,” he asked my mother to find something for me to play with. I was lying on my front on a rug on the lawn. Candy watched my mother disappear and silently moved in next to me, just to make sure the man with the camera didn’t whisk me away. The best photos are of Candy and me together.

Later that day, Mum shut Candy and Bertie, the lurcher, in the house and headed off down the steep drive with me in the stroller. She was wearing a new coat, which changed her outline from behind. She heard a noise and, when she turned around, she saw a slightly wonky-looking boxer trotting down the drive, barking a low, gruff warning alarm.

“Candy, what are you doing here?” she said.

Candy looked a bit dazed, as well she might. She had clearly thought that I was being abducted, so she’d thrown herself out of a top-floor window.

She had tried the back door, the front door and all the windows on the ground floor but found them locked. So she’d run up the stairs and discovered one window that was slightly ajar. Pushing hard, she had squeezed through the gap and jumped the twenty feet down to the ground. Her job was to protect me, and protect me she damn well would.

She suffered only a mild concussion and recovered quickly.

When Candy was nine years old, my parents took a rare holiday. My mother was persuaded, against her better judgment, to send her and Bertie to a kennel. What happened is still a mystery but it seems that Candy had a heart attack. She died before my mother returned.

Mum has never since sent a dog to a kennel. It wasn’t the kennel’s fault, she knows that, but she still frets that Candy must have felt abandoned and confused, that she wouldn’t have known she was being left there only for a fortnight, that she must have panicked and weakened her heart with anxiety.