2.

Mill Reef

The year was 1971. Specify beat Black Secret by a neck to win the Grand National under a jockey called John Cook, wearing the colors of Fred Pontin, the owner of Pontin’s holiday camps.

I do this, I’m afraid. Mark my years by Grand National or Derby winners. Sometimes I do it by Olympics—give me a year and I’ll tell you where the Olympics were held, but that only works every four years, so Grand Nationals and Derbies are more precise.

In 1971, the Derby winner was a little horse called Mill Reef. He was one of the true greats. He’s still talked about as one of the best Derby winners ever. He’s also the only Derby winner I’ve ridden—well, sat on. But there’s a photo to prove it and everything. I’m wearing red cords, blue Wellington boots, a blue sweater and a red balaclava. I am a vision in red and blue.

I’m leaning forward like a jockey but there’s no saddle. I’m turning to the camera and smiling. I have a light grip on the reins and no one is holding me.

Hang on a minute . . . no one is holding me and no one is holding him. What the hell is going on here? I’m barely eighteen months old, I’m on a four-year-old colt who the year before had won the Derby, the Eclipse, the King George and the Arc, and earlier that year had won the Coronation Cup. Alone. There isn’t an adult in sight.

He could have bolted, I could have lost my balance and smashed my skull on the floor. Just one step sideways and I’d have been a mess. Clearly that mattered little to the people around the great horse—that is, my parents.

My dad cries when he talks about Mill Reef, because he knows he owes that brave little bay horse everything. I once met a man who bought his first house with the money he won on Mill Reef in the Derby. My father never put a penny on him and yet could claim to have won his career and lifestyle because of him.

Ask my father what happened in 1971 and he’ll tell you how disappointed he was when Mill Reef was beaten by Brigadier Gerard in the 2000 Guineas, how easy he was to train, how he had a serenity and inner confidence, how when he first saw him gallop it was like watching a ballerina float across the stage: his hooves barely touched the ground before they sprang up into the next stride. He was neat, compact—some might say small—but he was nimble, agile and fast.

Strong fitness training for racehorses, when they gallop fast in pairs or threes, is called “work.” It happens twice a week—at Kingsclere, where my father trained, the horses walk for twenty minutes up to the Downs on a Wednesday and a Saturday, and that’s where they do their serious work.

Some horses work moderately and improve on a racecourse; others show it all at home and are disappointing on race day. Mill Reef was so good at home that he needed one horse to lead him for the first half of the gallop and another one to jump in halfway to stay with him to the end. No horse was good enough to stay with him for the whole length of the gallop. When he got on a racecourse, he was even better.

Dad will tell you how he got stuck in traffic on the way to Epsom and had to run the last two miles to make sure he was in time to put the saddle on Mill Reef for the Derby. He might admit that he had a funny feeling that Mill Reef was going to win the greatest flat race of all, but even he didn’t know that this wonderful horse would do it so easily.

What he will forget to tell you, if you ask him what else happened in 1971, is that I was born.

~

No one was prepared to rush my grandmother out of her home, so she took her time. When she was ready, Grandma built a new house across the road and painted it pink. We called it “The Pink Palace.” There she would reign for a further fifty years.

The rooms at Park House were used as living quarters for the stable staff, and it acquired an air of faded glory. Now in a new house not far away, my mother was removed from the workings of the yard, and a safe distance away from Grandma, but she was also disconnected from her husband, who worked every day of the week.

My mother might see him if he popped in to change, but often he jumped in the shower, pulled on a suit and dashed off to the races. He would come back in time for evening stables and then, finally, some time after seven, he would arrive at the house with a large board that looked like a ladder of narrow slats. “The Slate” was sacrosanct.

Into each horizontal runner on the board, he would slide the name of a stable lad, and either side of it the name of a horse. The horse to the left of the name would be his ride for First Lot and the name to the right of it the one he would ride out Second Lot. The names of horses and lads were printed with a Dymo Maxi printing gun. It had a wheel with letters on it that would imprint in white on to colored plastic tape. The horses were color-coded according to their age, and the human names were all in blue.

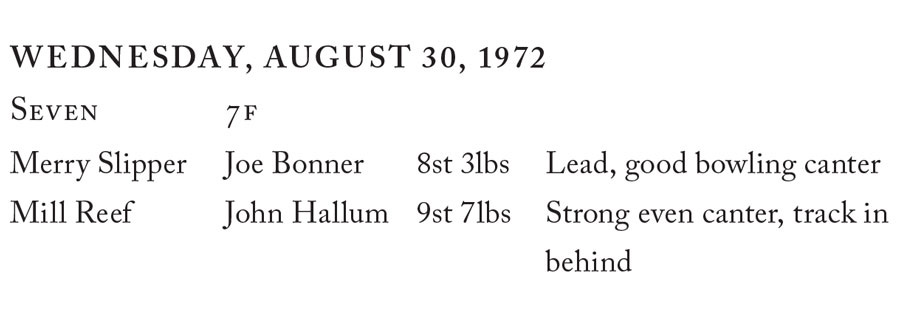

It took a fair amount of planning, and on Wednesdays and Saturdays there was “work” to be sorted out. My father did not like to be interrupted while he made his lists on paper with his all-color Biro: black for the date and for the horses’ names; blue for the riders and their weight; green for the gallop to be used, the distance to be covered and the instructions; red for the comments (written afterward) on how they had worked.

In the summer of 1972, Dad had planned a strong, bowling canter for Mill Reef on the Seven Gallop (so named because it was seven furlongs in length). Not a full piece of work—he wasn’t ready for that—but a gallop fast enough to ascertain how well he was and how much fitness work he would need before he could run again. John Hallum, who always rode him at home, was on board and set off behind Merry Slipper, who was going as fast as he could. Mill Reef—or Jimmy, as John called him—was swinging along in his usual fluid way.

It was and still is quite rare for a Derby winner to be kept in training as a four-year-old, but Paul Mellon, the American philanthropist who owned him, believed that racing was about being a good sport. The latest Derby winner is the headline horse—he can earn millions in his first season at stud. The risk of keeping him in training is that he may not improve or, even worse, he might deteriorate and therefore devalue his earning potential as a stallion.

In this case, the gamble of keeping Mill Reef in training had turned out well—he had won a Group 1 race in France that spring by ten lengths and the Coronation Cup in a tight finish at Epsom in June. Dad was worried about the way he’d struggled in that race and got the vets to check him over. He was found to be suffering from “the virus.” He was sick.

“The virus,” as all trainers call it, is an unspecified illness that can sweep through a yard, affecting all the horses to a greater or lesser degree. How it is caused is a mystery, and even stranger is how it suddenly disappears. The symptoms are hard to spot because the horses are generally fine at home. They work well, they eat up, they look healthy in their skin but, when it comes to racing, they run out of puff at the crucial stage and abruptly look as if they are treading water. Most ordinary horses finish nearer last than first when they have the virus. Mill Reef still managed to win, but he wasn’t right.

So he was given time over the summer to recover, and this gallop in late August was part of his preparation for another tilt at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris on the first Sunday of October. It’s the most stylish, glamorous occasion in the racing calendar. I have presented the Arc on television many times and I love it—as a sporting event, as a fashion parade and as a reminder that the French do things with such, as they would say, élan.

When Mill Reef careered away with the Arc in 1971, he was the first British-trained winner since 1948 and, if he could retain it, he would be the only British-trained horse ever to win back-to-back Arcs. It was with this elusive challenge in mind that Mill Reef was winging his way up the Seven Gallop early that morning.

My father was sitting on a horse farther up the gradual incline so that he could watch the final, fastest two furlongs and assess the fitness of his star. The heat was not yet in the sun. It was a bright day, the grass slightly browned by the summer months. My father loved the view from up there. He could look north from the height of the Downs, right across Berkshire and Hampshire, as far as Reading, sixteen miles away. He loved it there. He was a lucky, lucky man.

That bubble was about to burst and, for the first time in his life, neither his luck nor his charm would save him.

He heard the distant pounding of hooves. Mill Reef and his lead horse, Merry Slipper, came thundering by, their nostrils flaring, their coats gleaming like polished mahogany in the early-morning sun. John Hallum was crouched over Jimmy’s neck, his soft peaked cap turned backward so that it didn’t blow off in the wind, his reins tight, holding the horse together as he lengthened his stride and quickened his pace. He was moving well, looking good and, with a satisfied smile, my father turned to watch the next pair coming up the gallop.

As he followed that second pair with his eyes, sweeping his gaze from right to left, he noticed something strange. The first pair of horses were not at the top of the gallop as they should be, gently pulling up to a trot and turning to walk back along the track. Instead, one of them was standing to the side of the gallop, with only three legs on the ground. It was—oh God, he thought, it couldn’t be—it was Mill Reef.

John Hallum was holding him, trying to keep him calm as the other racehorses galloped past.

Dad’s heart stopped. He started shouting at the work riders coming up the gallop, “Pull up! Pull up!”

He then turned and cantered with dread toward John and Mill Reef.

“I heard a crack, Guv’nor. It’s not good,” said John, his quiet voice faltering.

The horse, whose galloping motion was so smooth and so easy, had suddenly shuddered. John had realized in an instant that something was badly wrong and pulled on the reins immediately to stop Mill Reef doing further damage to himself.

John, the man who loved and cherished this horse even more than my father did, was cradling Mill Reef’s head into his chest to stop him moving, stroking his face and whispering into his ear, “It’ll be all right, Jimmy. It’ll be all right.”

Mill Reef had fractured the cannon bone between the knee and the ankle of his front left leg. He was holding it above the ground, a look of confusion in his eyes, pain searing through his body.

Most racehorses will not stand still when they are hurting—they thrash, they bite and they try to gallop away from the thing that is causing them pain, injuring themselves further in the process. Mill Reef stood still. John kept whispering in his ear, telling him that the pain would stop soon, that he was a champion, that it would be all right.

Both John and my father knew that it would not be all right. They knew Mill Reef would never race again.

When a human breaks a leg, they can recover on crutches, taking the weight off the bad leg and allowing the bone to heal. A horse can’t do that and, for most, the suffering is too great to make an operation viable. In 1972, it was rare, if not unheard of, for a horse with a fractured cannon bone to survive.

My father and John both understood the gravity of the situation. Mill Reef had to be saved, whatever the cost. This wasn’t just a commercial decision. Their world had revolved around that horse since the day he had arrived in the yard. If my father knew anything about love, he knew he loved this horse.

Time must have dragged for the next hour. Grandma had been watching work and drove back in her car to the yard as fast as she could. She organized for the horse trailer to get to the top of the Downs and sent for the vet. Riders often fell off on the gallops but, thankfully, accidents are not an everyday occurrence. Perhaps once or twice in a season there would be a serious injury, but the chances of this happening to the best horse in the yard were 100:1. It was utterly shocking that it should happen to not only our best horse but the best horse in the country.

All that time, John kept talking to Mill Reef—not as a Derby winner, a champion, a superstar, but as Jimmy: his friend, the horse that he adored.

More remarkable than the way in which this beautifully balanced racehorse had, on the course, sailed past those stronger, bigger and more muscular than him was the way in which he allowed himself to be saved. He trusted John and he trusted my father, so he hobbled up the ramp into the horse trailer and was gently taken on the short journey back to the yard.

John talked to him all the while and stayed by his head as the vet examined him. “He knows what he’s doing, boy,” he murmured into Mill Reef’s ear. “He’ll sort you out.”

The vet did sort him out, but the horse would have known nothing about the plate and the three screws that were inserted into his front leg until he came around from the anesthetic. The whole operation was done on-site, in a large square room that had once been a chapel. Paul Mellon had instructed my father to do whatever it took, at whatever cost, to save the horse. When my father had called him in America, Mr. Mellon’s first question was, “Poor John—is he all right?” He knew how much his horse meant to the man who every day groomed him, fed him, mucked him out and rode him.

The recovery room was covered in the thickest, freshest straw, banked up at the sides. Mill Reef was never alone. Either John, my father or Bill Palmer would sleep in there with him while he lay with his left foreleg in plaster.

Eventually, Mill Reef could stand and, as his recovery progressed, so the attention increased. He had hundreds and hundreds of cards on lines of string in the recovery room, and the BBC had a live TV link-up with my father during Sports Personality of the Year in December 1972 to see how the patient was progressing.

The plaster was eventually removed, and Mill Reef could walk. He hobbled at first, unsure of how to put one leg in front of the other, but as he realized that it no longer hurt to place his weight evenly on all four legs, so he gained in confidence. Shortly after that, I was lifted onto his back and the photograph was taken. A last snapshot of Jimmy at home.

With every day that Mill Reef gained in strength, so John Hallum knew that his time with him was running out. Mill Reef’s life had been saved, but his racing career was over, and that meant his stay at Kingsclere was coming to an end.

John went in the horse trailer with him to the National Stud and wept as he kissed Mill Reef good-bye.

“It’s all change for you now, my boy. What a life you’ll have,” he explained to his friend. “Mares will come and visit you, so you be polite and always say thank you.

“This is your lovely new home in Newmarket, with all you can eat and huge fields to gallop in. You’ll want for nothing, I promise you, nothing. I’ll come and visit you to see how you’re getting on, you see if I don’t. Be a good boy now, Jimmy. Be a good boy.”

John was true to his word, and every time Mill Reef heard his footsteps approaching and his gentle voice he would whicker in recognition and fondness.

A film, Something to Brighten the Morning, was produced, with Albert Finney doing the voiceover, to tell the story of Mill Reef. He was the champion cut down in his prime, the perfect little package who had taken on and beaten bigger beasts. He had faced his toughest battle of all away from the racecourse, and he had won that too.

After Mill Reef had retired to stud, Mr. Mellon wrote to my father.

“Dear Ian, I’d like to do something special for you as a friend,” he proposed in his elegant handwriting, “and I would prefer to do it now rather than waiting until the day my will is read. Mill Reef brought me so much pleasure and you were masterful with him. I’d like to set up a trust fund for you and your children. You can do anything you like with it and, if you’re careful, it will last long beyond your lifetime.

“I do hope this will be useful to you, and in any case it comes to you with my warmest affection and regards, and my continued thanks for all you have done to make racing in England a tremendous pleasure. Yours ever, Paul.”

My father read the letter again and again. He could hardly believe it. He carried so much guilt for the way in which Mill Reef had broken his leg. He questioned himself endlessly—what if I hadn’t used that gallop? What if I’d sent him up second rather than first, would it still have happened? Not that he would have wished such a painful and life-threatening injury on any horse, but the question remained, why did it have to be him? Why the best horse he would ever train? Why?

Yet here was Mr. Mellon—he was always “Mr. Mellon”—thanking him and offering him a life-changing reward. My father knew that he would never have a chance like this again. Owners were not all as philosophical and as altruistic as Paul Mellon. He wrote straight back, “Thank you. That is an extraordinary offer and I would like to use your generosity to fund my children’s education. Emma and I have no savings to speak of and can’t afford to send them to the best school, but we will make sure they make the most of this opportunity. Thank you so much.”

Eighteen years later, when I was at Cambridge University, I sent Mr. Mellon a letter to express my gratitude for the education he had funded.

He sent me a postcard back with a picture of Clare College on it. He had studied there and used their black and gold college colors as the inspiration for his racing colors. It read:

A picture of Clare for Clare,

You need not thank me. I have watched from afar and you have more than fulfilled your side of the bargain. Be lucky, be happy and stay true to yourself.

With much love,

PM

As for Mill Reef, he passed on his brilliance to his progeny and, in doing so, became a champion sire: his son, Shirley Heights, would win the Derby in 1978. He eventually died in 1986, of heart failure, the year before another son, Reference Point, would also win the Derby.

There is a statue of Mill Reef at the National Stud, where he spent the majority of his life. Under it is an inscription from a speech that Paul Mellon gave about him. The last line reads: “Though small, I gave my all. I gave my heart.”

There is also an exact replica of that statue in the new yard that my father built the following year. He called it the Mill Reef yard. New visitors to Park House are shown that statue and told the story of the greatest horse he ever trained—the horse who encapsulated the mighty swing for Dad from a charmed life to the brutal reality of a world where everything would not always go his way.

Sometimes, early in the morning or when evening stables have finished, you will find my father standing alone looking at that statue.