CHAPTER 11

Tocqueville and the Dilemmas of Democracy

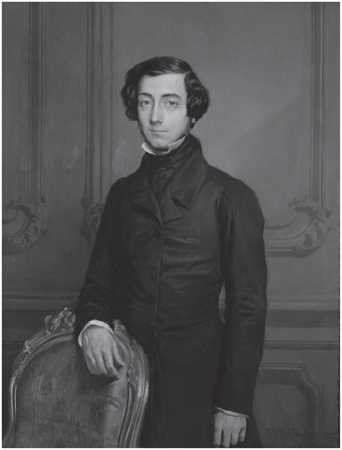

Charles Alexis Henri Clerel de Tocqueville, 1805–1859. 1850. Oil on canvas. Photo credit: The Art Gallery Collection / Alamy

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the ideas of freedom and equality walked confidently hand in hand. Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau all believed that in the state of nature men were born free and equal. As long as the enemy appeared to be entrenched hierarchies of power and privilege, freedom and equality were taken as mutually reinforcing aspects of the emergent democratic order.

It was not until the new democracies or proto-democracies began to take shape at the beginning of the nineteenth century that political philosophers began to wonder whether equality and liberty did not in fact pull in different directions. Tocqueville in particular—although we could add the names of Benjamin Constant and John Stuart Mill—saw the new democratic societies as creating new forms of power, new types of rule that represented organized threats to human liberty. These were the middle-class or bourgeois democracies emerging in France, England, and, of course, the United States. The question for Tocqueville was how to mitigate the effects of this new form of political power.

A standard answer to this question, taken up by the American constitutional framers, was to divide and separate powers. Tocqueville was less certain that this institutional device of checks and balances would be an effective safeguard in a democratic age where the people as a whole had become king. As I mentioned toward the end of the previous chapter, while seventy-five years before him Rousseau had taken the doctrine of popular sovereignty to be an ideal to be worked for, Tocqueville considers it to have come of age in the era of Jacksonian America:

In the United States, the dogma of the sovereignty of the people is not an isolated doctrine that is joined neither to habits nor to the sum of dominant ideas; on the contrary, one can view it as the last link in a chain of opinions that envelops the Anglo-American world as a whole. Providence has given to each individual, whosoever he may be, the degree of reason necessary for him to be able to direct himself in things that interest him exclusively. Such is the great maxim on which civil and political society in the United States rests: the father of a family applies it to his children, the master to his servants, the township to those under its administration, the province to the townships, the state to the provinces, the Union to the states. Extended to the entirety of the nation, it becomes the dogma of the sovereignty of the people. (I.ii.10 [381])

For Tocqueville, there was no reason to believe that the new democratic states ruled by the people will be more just, or less arbitrary, than any other previous form of rule. No one—no person or body—can be safely entrusted with power, and the united power of the people is no more reliable as a guarantee of freedom than any other regime. The problem of politics in an age of democracy is how to control the sovereign power of the people. Who can do this?

In aristocratic ages, Tocqueville believed, there had always been countervailing centers of power. Kings had to deal with an often fractious nobility. But who or what can exercise this role in a world where the people in their collective capacity are sovereign? Who or what has the power to check the popular will? This is the problem that Tocqueville’s political science—“a new political science for a world itself quite new”—set out to answer. To this extent we are all Tocqueville’s children, insofar as we are all dealing with the problem of the guidance and control of democratic government, of how to combine popular government with political judgment.1

Who Was Alexis de Tocqueville?

Alexis de Tocqueville was born in 1805 to a Norman family with an ancient lineage. The Tocqueville estate still exists and is still owned by members of the family. Tocqueville was deeply attached to his ancestral home and in 1828 wrote: “Here I am finally at Tocqueville in my old family ruin. A league away is the harbor from which William set out to conquer England. I am surrounded by Normans whose names figure in the list of the conquerors. All of this, I must admit, flatters the proud weakness of my heart.”2 Tocqueville’s parents had been arrested during the French Revolution and were held in prison for almost a year. Only the fall of Robespierre in 1794 saved them from execution. The young Tocqueville was born under the Napoleonic dynasty and spent his formative years in what might be called the most conservative, if not reactionary, circles of postrevolutionary France.

Tocqueville studied law in Paris and sometime during the late 1820s made the acquaintance of another young aristocrat by the name of Gustave de Beaumont. In 1830 the two men received a commission from the new government of King Louis Philippe to go to the United States in order to study the prison system there. Tocqueville’s journey to America, which has been extensively documented, lasted for a little over nine months, from May 1831 to February 1832.3 During that time he traveled as far north as New England, south to New Orleans, and west to the outer banks of Lake Michigan. The result of this visit was, of course, two large volumes that he called Democracy in America. The first volume appeared in 1835, when its author was only thirty years of age, and the second volume five years later, in 1840. A few years ago another Frenchman, Bernard-Henri Lévy, toured America and hit all the high spots—Las Vegas, evangelical churches—in order to do an update of Tocqueville in his book American Vertigo.4 The most charitable comparison one could make between Tocqueville and Lévy would be to say that there is no comparison.

Democracy in America is, to put it simply, the most important work about democracy ever written. To compound the irony, the most famous book on American democracy was written by a French aristocrat. From the time of its first publication, the book was hailed by no less an authority than John Stuart Mill as a masterpiece, “the first analytical inquiry into the influence of democracy” and the beginning of “a new era in the scientific study of politics.”5 Tocqueville has virtually taken a place alongside Washington, Jefferson, and Madison as an honorary American, and, as if this were not enough, his book was recently inducted into the prestigious Library of America series, setting upon it the mark of naturalization.

There is a textbook image of Tocqueville according to which the young aristocrat came to America as a kind of blank slate and was profoundly transformed by his experience of American democracy. Nothing could be farther from the truth. In a letter to his best friend, Louis de Kergolay, written just before the publication of the first volume of Democracy, Tocqueville describes his purpose in writing the book as follows:

It is not without having carefully reflected that I decided to write the book I am just now publishing. I do not hide from myself what is annoying in my position: it is bound to attract active sympathy from no one. Some will find that at bottom I do not like democracy and I am severe toward it; others will think I favor its development imprudently. It would be most fortunate for me if the book were not read, and that is a piece of good fortune that may perhaps come to pass. I know all that, but this is my response: nearly ten years ago I was already thinking about parts of the things I have just now set forth. I was in America only to become clear on this point. The penitentiary system was a pretext.6

Two points about this letter bear comment. First, Tocqueville indicates that his idea for the book had already begun to germinate five years before his trip to America—he was hardly a blank slate. If you consider that he was only thirty when the first volume was published, that means that parts of the book had already become clear to him when he was only about twenty years old—the age of a college undergraduate! He came to America to confirm what he had already begun to suspect.

Second, Tocqueville was writing the book not for the benefit of Americans, who he thought had little taste for philosophy, but for Frenchmen. In particular he was hoping to persuade his fellow countrymen who were still devoted to the restoration of the monarchy that the democratic social revolution he had witnessed in America represented the future of France. If John Locke had said that “in the beginning all the world was America,” Tocqueville’s point was that in the future all the world will be America. His attitude toward what he saw was one of cautious skepticism mixed with hope. “I confess that in America I saw more than America; I sought there an image of democracy itself, of its penchants, its character, its prejudices, its passions; I wanted to become acquainted with it if only to know at least what we ought to hope or fear from it” (Preface [13]).

There are two questions that Democracy sets out to answer. The first concerns the gradual replacement of the ancien régime, the French term for the old aristocratic regime based on the principles of hierarchy, deference, and inequality, with a new democratic society based on equality. How did this happen, and what brought it about? The second, not explicitly asked but present on virtually every page of the book, concerns the difference between the form democracy had taken in America and the form it took in France during the revolutionary period. Why has American democracy been relatively gentle or mild—what we might call a liberal democracy—and why did democracy in France veer dangerously toward terror and despotism? Tocqueville believed it to be virtually a providential fact of history that society was becoming increasingly democratic. What is not certain is what form this democracy will take. Whether democracy will be compatible with liberty or whether it will issue in a new kind of despotism remains a question that only the statesmen of the future will be able to answer.

From these two questions we can see that Tocqueville wrote his book as a political educator. More than a mere chronicler of American manners and customs, he was a teacher of future European statesmen hoping to steer their countries between the shoals of revolution and reaction. Let us see further exactly what Tocqueville hoped to teach.

The Age of Equality

Near the end of the Introduction to the first volume of Democracy Tocqueville writes: “I think those who want to regard it closely will find, in the entire work, a mother thought that, so to speak, links all its parts” (14). What is this “mother thought” or mother idea to which Tocqueville refers? The most likely candidate is the idea of equality. The opening sentence of the book reads: “Among the new objects that attracted my attention during my stay in the United States, none struck my eye more vividly than the equality of conditions” (3). What does Tocqueville mean here by equality?

Note that Tocqueville speaks of equality as a social state (“equality of conditions”) rather than a form of government. This is in part an expression of Tocqueville’s sociological imagination. Equality of conditions precedes democratic government. It is the cause from which democratic government arises. Equality of conditions was planted in both Europe and America long before democratic governments arose in either place. Democratic governments are only as old as the American and French revolutions, but equality of conditions had been prepared by deep-rooted historical processes long before the modern age came into being.

In the Introduction Tocqueville gives a brief—very brief—history of equality, taking it back to the heart of the medieval world seven hundred years before. Unlike Hobbes or Rousseau, he does not invoke a state of nature as a way of grounding equality. In fact, while Hobbes and Rousseau believed that we are by nature free and equal and that only over time were social hierarchies and inequalities introduced, Tocqueville argues the opposite. The historical process has been moving away from inequality and toward greater and greater equality of social conditions. Equality is a historical force, something that has been working itself out in history over a vast stretch of time. Tocqueville often writes of equality not just as a “fact” but as a “generative fact” from which everything else derives: “As I studied America, more and more I saw in the equality of conditions the generative fact from which each particular fact seemed to issue,” he writes in the third paragraph of the book (3).

Tocqueville writes about equality as a historical fact that has come to acquire almost providential force. He uses the term “providence” to describe a universal historical process that is constantly working, so to speak, even against the intentions of individual actors. The kings of France, for example, who struggled to subdue the power of the nobility were working—unbeknownst to them—to hasten the equality of social conditions. The gradual spread of conditions of equality has two characteristics of providence: it is universal, and it always escapes the powers of human control. It is the very power of equality that makes it seem an irresistible force. Tocqueville shows that rather than being the product of the modern age alone, the steady emergence of equality has been at the heart of European history for centuries.

It is in order to understand the advance of equality that Tocqueville turns to America of the 1830s. “There is only one country in the world,” he writes, “where the great social revolution I am speaking of seems nearly to have attained its natural limits” (12). That country is, of course, America. In this context it is revealing that he chose to call his book Democracy in America and not American Democracy. His point is not that democracy is a peculiarly American phenomenon; far from it. His point is to show the form that the democratic revolution has taken in America. What form it will take elsewhere is by no means predetermined. Democracy is not a condition but a process. It has the quality that Rousseau described as perfectibilité, an almost infinite elasticity and openness to change. It is less a determinate regime than a perpetual work in progress.

This is an extremely astute observation. Democracy is the only regime form that has become a verb. We do not know where the process of democratization will end or what form it will take elsewhere. Will future democratic regimes be liberal and freedom loving or harsh and rebarbative? This question is at least as important for us as it was for Tocqueville. What Tocqueville is sure about is that the fate of America is the fate of Europe and maybe the fate of the rest of the world. “It appears to me beyond doubt that sooner or later we shall arrive, like the Americans, at an almost complete equality of conditions,” he remarks (12). Do you like what you see? he seems to ask his readers. What form democracy will take elsewhere will be dependent on circumstances and statesmanship. His is an attempt to educate the statesmen of the future.

Democracy American Style

It is important to remember that Democracy in America was published in two volumes, five years apart. Some interpreters of the work have even taken to referring to them as Democracy I and Democracy II. Democracy I deals far more with American materials; Democracy II with the problems of democracy in general. Democracy I is also more optimistic about the structure of democracy; Democracy II is characterized by a far deeper pessimism about democracy’s fate. How to account for these differences? Let us consider first, however, Tocqueville’s account of American democracy in Democracy I.

There are three features of American democracy that Tocqueville isolates and that account for what contributes to a flourishing democratic state. These are: local government, civil associations, and what he calls the spirit of religion. I will consider these in order.

The first and perhaps most fundamental feature of American democracy is the importance given to local government and local institutions. The importance of localism—and the spirit that emanates from it—is the key to the whole. The cradle of democracy is to be found in what Tocqueville calls the commune or the township. “It is nonetheless in the township that the force of free peoples resides. The institutions of a township are to freedom what primary schools are to science; they put it within reach of the people; they make them taste its peaceful employ and habituate them to making use of it. Without the institutions of a township a nation can give itself a free government, but it does not have the spirit of freedom” (I.i.5 [57–58]).

Does this sound familiar? It should. Tocqueville’s description of the New England township breathes the spirit of Rousseau’s general will. It is the people organizing, legislating, and deliberating over their common interests that is the core of liberty. This coincidence is hardly fortuitous. In the letter to Kergolay cited in the previous chapter, Tocqueville admitted that Rousseau was one of three writers with whom he spent time every day. It is Rousseau more than any other writer who crafted the lenses through which Tocqueville observed democracy.

Yet Tocqueville combines Rousseau with an Aristotelian twist: “The township,” he continues, “is the sole association that is so much in nature that everywhere men are gathered a township forms by itself” (I.i.5 [57]; emphasis added). The township is said to be a product of nature, it “eludes, so to speak, the effort of man.” The township exists by nature, but its existence, far from being guaranteed, is fragile and uncertain. It is continually threatened by invasions, not by foreign powers, but from larger forms of government. The township is continually threatened by federal or national authority, and Tocqueville adds, with a definite hint of Rousseau, that the more “enlightened” a people are, the more difficult it is to retain the spirit of the town. The spirit of local freedom goes hand in hand with rustic, even primitive, manners and customs. For this very reason, he laments, the spirit of the township no longer exists in Europe, where the process of political centralization and the progress of enlightenment have destroyed the conditions for local self-government.

Tocqueville’s celebration of the township form of government is supported by another pillar of democracy: civil associations. This is the part of Democracy in America that has received the most attention in recent years. “In democratic countries,” Tocqueville writes in one of the most famous sentences in his book, “the science of association is the mother science; the progress of all the others depends on the progress of that one” (II.ii. 5 [492]).

It is through uniting and joining together in common endeavors that people develop a taste for liberty. “In America I encountered sorts of associations of which, I confess, I had no idea, and I often admired the infinite art with which the inhabitants of the United States managed to fix a common goal to the efforts of many men and to get them to advance to it freely” (II.ii.5 [489]).

It is in the importance he attributes to local voluntary groups and associations that Tocqueville seems to depart most widely from Rousseau. Rousseau, recall, had warned against “partial associations” for their tendency to frustrate the general will. Tocqueville, on the other hand, regards voluntary associations of all sorts—interest groups, as we might call them—as the place where we learn habits of initiative, cooperation, and responsibility. By taking care of our own interests, we learn to take care of others. “Sentiments and ideas renew themselves,” Tocqueville writes, “the heart is enlarged and the human mind is developed” (II.ii.5 [491]). It is through free associations—volunteer groups, PTAs, churches, synagogues, unions, and other parts of civil society—that institutions are formed that can resist the power of centralized authority. It is in such associations that we learn how to become democratic citizens.

The argument about the necessity of civil association has been taken up recently by political scientist Robert Putnam in his book Bowling Alone.7 Here Putnam speaks about “human capital”—what Tocqueville called mores or the habits of mind and heart—that is developed through civic association. Putnam’s chief example is the bowling league. He is concerned with the decline of such associations in contemporary America. More and more, Putnam complains, people choose to bowl alone, and this tendency toward isolation represents a danger to our civic capacities. Have our capacities for joining with others been eroded by forces of modern society and technology? Are we becoming more and more a nation of solitaries and couch potatoes?

These are serious questions, and a large literature has grown up around them. Some of this literature suggests that Putnam’s findings are overdrawn and that he exaggerates the decline of membership in civic organizations like Rotary Clubs and bowling leagues. Still others suggest that he overstates the relation between civic organizations and democracy. Many voluntary associations are exclusionary, whether along racial, ethnic, or gender lines. The Ku Klux Klan and the Aryan Nation are voluntary groups, but they are hardly teaching the lessons in democracy that either Tocqueville or Putnam would want us to learn. Is it even clear that clubs like bowling leagues make good citizens? Consider the Coen brothers’ great film The Big Lebowski. In the movie the Dude, Walter, and Donny are avid bowlers, and their great ambition is to enter the finals. The Dude is a stoned hippie, Walter a psychologically damaged Vietnam vet, and Donny a lost waif. Standing in their way is Jesus Quintana, a convicted sex offender (“That creep can roll,” Walter says). These men are all members of the same bowling league. Are they Putnam’s ideal democratic citizens? Is their team a model of civil association?

The third and final leg of the stool on which American democracy rests is what Tocqueville calls “the spirit of religion.” “On my arrival in the United States,” he observes, “it was the religious aspect of the country that first struck my eye” (I.ii.9 [282]). Like other European observers, then as well as now, Tocqueville was perplexed by the fact that in America the spirit of democracy and the spirit of religion have worked hand in hand. This is virtually the exact opposite from what has occurred in Europe, where religion and democracy have generally been on a collision course. What accounts for this peculiarity of American democratic life?

In the first instance Tocqueville notes that America is a uniquely Puritan democracy. “I see the whole destiny of America contained in the first Puritan who landed on its shores, like the whole human race in the first man” (I.ii.9 [267]). America was created by a people with strong religious habits who brought to the New World a suspicion of government and a strong desire for independence. This contributed to the separation of church and state that has done so much to promote both religious and political liberty.

Tocqueville drew two important theoretical conclusions from the fact of religious life in America. First, the thesis propounded by the philosophers of the Enlightenment that religion would wither away with the advancement of modernity is demonstrably false. “The philosophers of the eighteenth century,” he writes, “explained the gradual weakening of beliefs in an altogether simple fashion. Religious zeal, they said, will be extinguished as freedom and enlightenment increase. It is unfortunate that the facts do not accord with this theory” (I.ii.9 [282]).

Second, Tocqueville regarded it as a terrible mistake to attempt to eliminate religion or to secularize society altogether. It was his belief—as it was for Rousseau as well—that free societies rest on public morality and that morality cannot be effective without religion. Individuals may be able to derive moral guidance from reason alone, but societies cannot. The danger of attempting to eliminate religion from public life is that the need or will to believe will find other outlets. “Despotism can do without faith,” Tocqueville remarks in an arresting sentence, “but freedom cannot. Religion is much more necessary in a republic and in a democratic republic more than all others” (I.ii.9 [282]). But why is religion so necessary to a republic?

Tocqueville gives a variety of answers. One persistent theme of Democracy is that only religion can resist the tendency toward materialism and a kind of low self-interest that is intrinsic to democracies. “The principal business of religions [in a democracy] is to purify, regulate, and restrain the too ardent and too exclusive taste for well-being that men in times of equality feel” (II.i.5 [422]).

Tocqueville also operates with a kind of metaphysics of faith that regards religious belief as necessary for the efficacy of human action. “When religion is destroyed in a people,” he writes, “doubt takes hold of the highest portions of the intellect and half paralyzes all the others” (II.i.5 [418]). This paralysis of the will is a condition that later writers would diagnose as nihilism. Faith is a necessary component for our belief that we are free agents and not simply the playthings of a blind and random fate. “Such a state [of disbelief],” Tocqueville asserts, “cannot fail to enervate souls; it slackens the springs of the will and prepares citizens for servitude” (II.i.5 [418]). Our beliefs about the freedom and dignity of the individual are inseparable from religious faith, and it is unlikely that these beliefs could survive without religion to support them. “As for me,” Tocqueville writes, “I am brought to think that if he has no faith he must serve, and if he is free, he must believe” (II.i.5 [418–19]). No more powerful challenge to the Enlightenment has ever been uttered.

One final issue remains. Tocqueville often writes as if religion is valuable only for the social function it serves. This is surely consistent with the sociological interpretation of his thought, and Tocqueville often writes as though he is concerned only with the social and political consequences of religion rather than with the truth of religious beliefs. “I view religions only from a purely human point of view,” he says (II.i.5 [419]). How accurate is this view?

The sociological or functionalist reading of Tocqueville only captures a part of his complex attitude toward religion. Tocqueville was a student not only of Rousseau but also of Blaise Pascal, the seventeenth-century religious philosopher who more than any other philosopher saw the emptiness of knowledge without faith. Man may be the rational animal, but our reason is as nothing before the unfathomable depths of the universe. “A vapor, a drop of water, is enough to kill him,” Pascal wrote. “Man is but a reed, the weakest in nature. But he is a thinking reed.”8

Tocqueville discovered in Pascal a sense of the existential emptiness and incompleteness of life that cannot be explained in rational terms alone. His fear was that of an individual cast adrift in the vast, infinite space of the universe. Furthermore, there is something about the equality of conditions that fosters an ominous sense of the loneliness of humanity cut off from grace and true communion with others. Tocqueville sought the limits of reason precisely to leave room for faith. “The short space of sixty years,” he writes almost as an aside, “will never confine the whole imagination of man; the incomplete joys of this world will never suffice for his heart” (I.ii.9 [283]). In other words, there is something we desire beyond the here and now that only faith can supply. The soul exhibits a longing, a desire, for eternity and a certain disgust with the limits of physical existence: “Religion is therefore only a particular form of hope and it is as natural to the human heart as hope itself. Only by a kind of aberration of the intellect and with the aid of a sort of moral violence exercised on their own nature do men stray from religious beliefs; an invincible inclination leads them back to them. Disbelief is an accident; faith alone is the permanent state of humanity” (I.ii.9 [284]). This passage shows that Tocqueville was more—much more—than a sociologist of religion. It addresses the metaphysical side of his thought and shows him to be a writer of great psychological depth and insight.

The Tyranny of the Majority

Although there was much in American democracy to admire—its town meetings, its spirit of civil association, its religious commitments, and so on—Tocqueville also identified in it dangerous tendencies toward democratic tyranny. He in fact offered two quite distinct analyses of this problem, one in volume 1 and the other in volume 2 of Democracy. What was the problem of democratic tyranny that Tocqueville feared?

In Democracy I he treated the problem of “tyranny of the majority” largely in terms inherited from Aristotle and the Federalist Papers. In the Politics Aristotle had associated democracy with the rule of the many, generally the poor, in their own interests. The danger of democracy was precisely that it represented the self-interested rule of one class of the community, the largest class, over the minority. Democracy was thus always potentially a form of class struggle exercised by the poor over the rich, often egged on by populist demagogues. This theme was considered by the Federalist authors. Their solution to the problem of majority faction was to “enlarge the orbit” of government in order to prevent the creation of a permanent majority faction. The greater the number of factions, the less likely any one of them would be able to exercise despotic power over national politics.

The chapter of Democracy entitled “On the Omnipotence of the Majority in the United States and Its Effects” should be read as a direct reply to the Federalist. The U.S. Constitution enshrined the majority (“We the People”) even as it sought to limit its power. Although Tocqueville devoted a lengthy chapter to the federal structure of the Constitution, he was less convinced than Madison that the problem of majority faction had been solved. In particular he was skeptical that the Constitution’s plan for a system of representation and checks and balances could serve as an effective check on “the empire of the majority,” a term that has clear theological evocations of the doctrine of divine omnipotence (I.ii.7 [235]). Rather than regarding the people in Madisonian terms as a shifting coalition of interest groups, Tocqueville tended to regard the power of the majority as unlimited and unstoppable. Legal guarantees of minority rights were not likely to be effective in the face of mobilized opinion.

Tocqueville’s image of majority tyranny was inseparable from the threats of revolutionary violence fueled by “charismatic” military leaders like Andrew Jackson and Napoleon capable of mobilizing the masses in fits of patriotic zeal. Jacksonianism was the American equivalent of Bonapartism in France, a military commander riding to power on the wings of popular support (I.ii.9 [265]). More than anything, Tocqueville feared this militarism combined with a kind of unlimited patriotic fervor. It is in America that one can begin to see the ennobling qualities of equality of conditions and also the more ominous possibilities of democratic tyranny.

The power of the majority makes itself felt first of all through the dominance of the legislature. “Of all political powers,” Tocqueville writes, “the legislature is the one that obeys the majority most willingly” (I.ii.7 [236]). In a dramatic moment in the text he cites Jefferson’s warning to Madison: “The tyranny of the legislature is the most formidable dread at present and will be for long years.” Tocqueville regards this warning as especially ominous because in Jefferson he finds “the most powerful apostle that democracy has ever had” (I.ii.7 [249]).

What is it about legislative tyranny that Tocqueville fears? As the title of the chapter indicates, it is not the causes of tyranny but its effects that is Tocqueville’s main concern. In the first place, Tocqueville takes issue with the belief that there is necessarily more wisdom in the many than the few. He describes this as “the theory of equality applied to brains” (I.ii.7 [236]). There may be strength in numbers, but not necessarily truth. And second, Tocqueville questions the idea that in matters of policy the interests of the many must always take precedence over the few. It is precisely the “omnipotence” of the majority, not any particular policy, that Tocqueville finds “dire and dangerous for the future” (I.ii.7 [237]).

Tocqueville cites two examples of how intolerant local majorities can violate the rights of individuals and minorities. In a footnote he recalls the story of two antiwar journalists in Baltimore during the War of 1812 when pro-war sentiment was running high. The two journalists were arrested for their opinions, taken to prison, and under cover of darkness murdered by a mob. Those who participated in the crime were later exonerated by a jury of their peers. Tocqueville then tells a story of how even in Quaker Pennsylvania freed blacks were unable to exercise their right to vote because of popular prejudice against them. He sums up this situation with the following barb: “What! The majority that has the privilege of making the law still wants to have that of disobeying it” (I.ii.7 [242]).

It is, however, in the realm of thought and opinion that Tocqueville believes the empire of the majority makes itself especially felt. In an always startling passage Tocqueville remarks: “I do not know any country where in general less independence of mind and genuine freedom of discussion reign than in America” (I.ii.7 [244]). The dangers to freedom of thought do not come from the fear of an inquisition, they come in the more subtle forms of exclusion and social ostracism. Tocqueville is perhaps the first and still one of the most perceptive analysts of what today would be called the power of “political correctness” to stifle thought, to render “unthinkable” that of which the majority does not approve.

Tocqueville’s statement that there is less freedom of discussion in America than in any other country known to him is clearly an overstatement intended to shock the complacent. His point is that persecution can take many forms, from the cruelest to the mildest. It is the very mildness—a term that Tocqueville uses throughout Democracy—of democratic exclusion that he regards as exercising a profound, chilling effect on the free expression of unpopular beliefs: “Chains and executioners are the coarse instruments that tyranny formerly employed; but in our day civilization has perfected even despotism itself which seemed, indeed, to have nothing more to learn.… Under the absolute government of one alone, despotism struck the body crudely, so as to reach the soul; and the soul, escaping from those blows rose gloriously above it; but in democratic republics, tyranny does not proceed in this way; it leaves the body and goes straight for the soul” (I.ii.7 [244]).

The Centralization of Power

Tocqueville’s account of the tyranny of the majority in the first volume of Democracy remained tied to a fear of mob rule and general lawlessness. The danger of “mobocracy” (as Abraham Lincoln called it) combined with the ambitions of popular demagogues was very real. For Tocqueville and those of his generation, the images of the mob were invariably tied to the memory of the National Assembly during the French Revolution. Revolution and tyranny were virtually synonymous for a range of postrevolutionary writers. But by the time Tocqueville wrote his second account of democratic despotism in the second volume of Democracy either the memory or the fear of revolution had begun to wane. What might account for this change of mind?

As the images of revolutionary violence began to recede in Tocqueville’s mind, a new threat arose to take its place. This was the danger of centralization. Tocqueville is often read as a critic of the centralization of power and a defender of local self-government, and this is more or less correct, but it only grasps a piece of the picture. Tocqueville was not opposed to the growth of state power per se; he was opposed to the rise of bureaucracy and with it the growth of the centralizing spirit as the most serious threat to political liberty.

The theme of centralization is a constant in Tocqueville’s thought, linking not only the two volumes of Democracy but also Democracy and his other great work, The Old Regime and the Revolution. The issue of centralization emerges early in Democracy I with Tocqueville’s distinction between political and administrative centralization (I.i.5). Political or governmental centralization Tocqueville regards as a good thing. The idea of a uniform center of legislation is greatly to be preferred to any system of competing or overlapping sovereignties such as existed in France under the old regime. Political centralization has made significant progress in the United States in part due to supremacy of the legislature.

The danger is not with centralization of the law-making function but with what Tocqueville calls “administrative centralization.” What does this distinction amount to? Tocqueville regards a centralized sovereign as necessary for the promulgation of common laws that pertain equally and equitably to all. Governmental centralization is required to ensure that equal justice is afforded to all citizens. Administrative centralization is another matter. The science of administration concerns not the establishment of common laws but the oversight of the details of conduct and the direction of the everyday affairs of citizens. It represents the slow and insidious penetration of the bureaucracy into every aspect of daily affairs. While governmental centralization is needed for the purpose of making laws and national defense, centralized administration is mainly preventative and produces nothing but languid and apathetic citizens who are unable to look after themselves.

Administrative centralization carries with it the germ of what today is called the regulatory state. It is the spirit of regulation that Tocqueville regards as enervating the initiative of citizens to act for themselves. This kind of regulation, he writes, “succeeds without difficulty in impressing a regular style of current affairs, in skillfully regimenting the details of social orderliness [and] in keeping in the social body a sort of administrative somnolence that administrators are accustomed to calling good order and public tranquility” (I.i.5 [86]). It is clear that what Tocqueville is anticipating here is the rise of what we would call the administrative state.

What led Tocqueville to focus on administrative centralization as a peculiar threat to liberty? In many ways this expresses a peculiarly French view of the world. When Tocqueville was writing in the first third of the nineteenth century, the development of the great regulatory agencies that we associate with the Progressive movement was still at least half a century away. Only in France did the centralization of administrative power go back deep into the heart of the old regime.

Tocqueville’s interest in the theory and history of the administrative state grew out of his reading of the dynamics of French history. The last twenty years of his life were devoted to the examination of French municipal archives to find the earliest evidence of the growth of centralized administrative power. Fully consistent with his Introduction to Democracy, he found that the emergence of a central bureaucracy was not a new development but went at least as far back as the reign of Louis XIV. The administrative conquests of the French kings did the most to produce the coming age of equality and the democratic revolutions. In his paradoxical formulation the Revolution merely completed what had been set in motion during the ancien régime. The broad tendency of history was toward the greater and greater concentration of administrative power, and this is what deeply worried Tocqueville.

Democratic Despotism

It is only at the very end of Democracy II that Tocqueville provides his final reflection on the administrative state, in a chapter ominously entitled “What Kind of Despotism Democratic Nations Have to Fear” (II.iv.6). Here we see him abandon his earlier concerns with the tyranny of the majority and the danger of mob rule for a new kind of power, the outlines of which are only now becoming legible. Tocqueville gives some indication of his change of perspective when he remarks near the outset of the chapter that “five years of new meditations have not diminished my fears but they have changed their object” (II.iv.6 [661]).

Tocqueville seems at first reluctant to define this new power. “I think that the kind of oppression with which democratic peoples are threatened,” he writes, “will resemble nothing that has preceded it in the world.” No longer is he concerned with the emergence of a revolutionary charismatic leader, the prototype of the military despot. Instead there will be no image for this new despotism in our memories. Even our language is inadequate to define it; “the old words ‘despotism’ and ‘tyranny’ are not suitable” (II.iv.6 [662]. What, then, is it?

One feature of Tocqueville’s new despotism that distinguishes it from tyrannies of the past is its very mildness or “sweetness” (douceur) (II.iii.1). The mildness of democratic habits and manners is a theme that runs throughout both volumes of Democracy. The equality of conditions has rendered men gentler and more considerate with respect to one another. Being more alike, we have, in the words of a recent American president, an enhanced ability to feel one another’s pain. “Do we have more sensitivity than our fathers?” Tocqueville asks with apparent incredulity. “I do not know, but surely our sensitivity bears on more objects” (II.iii.1 [538]).

The word douceur is, of course, a term that Tocqueville’s readers would have associated with Montesquieu’s description of commerce in his book The Spirit of the Laws. Commerce was seen by many of the great eighteenth-century writers—Montesquieu, Hume, Kant—as exercising a pacifying and purifying effect on a fierce and warlike people. Commerce makes people less harsh toward one another and more tolerant toward strangers. It is the cause of a new, more cosmopolitan ethic of l’humanité. Montesquieu regarded the transition from the feudal warrior ethic to the modern bourgeois commercial ethic as a marker of progress; Tocqueville, while also appreciating the contrast, drew less optimistic conclusions.

The fact that democracy has rendered people gentler in their habits and practices, Tocqueville writes, is no doubt preferable to the kind of deliberate cruelty and indifference to human suffering quoted in the letters of Madame de Sévigné to her daughter (II.iii.1 [537]). It has also, Tocqueville believes, rendered us more pliant and subject to manipulation. It is here that he coins the term “democratic despotism” for this new species of power that has so far defied definition. He describes this despotism as “an immense tutelary power” (un pouvoir immense et tutélaire) that keeps its subjects in a state of perpetual political adolescence (II.iv.6 [663]). It is, above all, the paternalism of the new administrative state that elicits his strongest reaction. “It was not tyranny, but rather being held in tutelage by government that has made us what we are,” Tocqueville writes in a marginal comment in volume 2 of The Old Regime. “Under tyranny, liberty can take root and grow; under administrative despotism, liberty cannot be born, much less develop. Tyranny can create liberal nations; administrative despotism, only revolutionary and servile peoples.”9

Tocqueville is clearly concerned with the effects of this new kind of soft despotism on the character of its citizens. It is not revolutionary outbreaks of uncontrollable passion that will characterize the democratic social order but rather an extreme form of docility and apathy, a quality that he terms “individualism” (II.ii.2 [482–84]). For Tocqueville individualism is not a term of praise but the name for a pathology unique to democratic times. It points to a condition of extreme isolation, anomie, and alienation. He defines it as “a reflective and peaceable sentiment [un sentiment réfléchi et paisible] that disposes each citizen to cut himself off from the mass of his fellow men and to withdraw into the circle of family and friends” (II.ii.2 [482]). The isolated individual was not the village eccentric or nonconformist—someone whom Tocqueville might have admired—but the eremite, the solitary, cut off from society altogether, and is in Tocqueville’s chilling phrase confined in “the solitude of his own heart” (la solitude de son propre coeur) (II.ii.2 [484]).

The fact that equality renders us alike also renders us indifferent to one another and our common fate. The democracy of the future is less likely to be a land of rugged individualists and freethinkers than of couch potatoes:

Thus after taking each individual by turns in its powerful hands and kneading him as it likes, the sovereign extends its arms over society as a whole; it covers its surface with a network of small, complicated painstaking uniform rules through which the most original minds and the most vigorous souls cannot clear a way to surpass the crowd; it does not break wills, but it softens them, bends them, and directs them; it rarely forces one to act, but it constantly opposes itself to one’s acting; it does not destroy, it prevents things from being born; it does not tyrannize, it hinders, compromises, enervates, extinguishes, dazes, and finally reduces each nation to being nothing more than a herd of timid and industrious animals of which the government is its shepherd. (II.iv.6 [663])

Has there ever been a more powerful and prescient description of the modern administrative state?

Tocqueville came to regard the rise of this soft despotism as ultimately more dangerous to liberty than his early concerns about majority tyranny. The image of this new kind of tutelary despotism anticipates what the English call the nanny state or what is sometimes called the therapeutic state. This state, in the words of Michael Oakeshott, “is understood to be an association of invalids, all victims of the same disease and incorporated in seeking relief from their common ailment; and the office of government is a remedial engagement. Rulers are therapeutae, the directors of a sanatorium from which no patient may discharge himself by a choice of his own.”10 While Montesquieu had located the principle of despotism in fear, Tocqueville sees it as acquiescence. With all countervailing powers under the administrative control of the state, citizens have no choice but to become its wards. “They console themselves for being in tutelage [en tutelle] by thinking they have chosen their schoolmasters [tuteurs]” (II.iv.6 [664]).

The Democratic Soul

It would be misleading to conclude a consideration of Tocqueville with his account of democratic tyranny. A brief perusal of the section headings of Democracy II shows that his deepest concerns were not just with the institutions of democracy but with the ideas, sentiments, and habits that form democratic life. Following Plato, one could say that Tocqueville’s most profound reflections concern the state of the democratic soul. What indeed are the traits and characteristics of democratic man described in Democracy?

There are three features of the democratic soul on which I would like to spend some time: compassion, restiveness, and self-interest. Taken together these features constitute the psychology, the moral scope, of the democratic state. In describing these character traits Tocqueville is providing a moral phenomenology of democratic life, one into which we are invited to look and ask whether we see ourselves and whether we like what we see.

The first and most important moral effect that democracy has on its citizens is its constant tendency to make us gentler toward one another. This is an old eighteenth-century theme. Montesquieu had argued that it was commerce that made manners milder, but it was Rousseau who made pity or compassion—a repugnance to view the suffering of others—a fundamental feature of natural man. Compassion remains a remnant of our natural goodness even amid the growth of more powerful and noisier passions. For Tocqueville, however, compassion is a feature not of natural man but of democratic man. It is not nature but democracy that has rendered us gentler, and led to the softening of mores and manners.

In a chapter entitled “How Mores Become Milder as Conditions Are Equalized” (II.iii.1 [535–39]), Tocqueville describes the moral and psychological consequences of the transition from an age of aristocracy to the age of democracy. Under aristocratic times, individuals inhabited a world where members of one class or tribe may have been like one another but regarded themselves as different from members of any other class. This did not make them cruel so much as indifferent to the pain and suffering of others outside their group. Under democracy, where all people are equal, “all men think and feel in nearly the same manner.” The moral imagination of the democratic citizen is able to transport itself into the position of others more easily than in aristocratic ages. All become alike—or at least are perceived as being alike—in their range of emotions, sensibilities, and capacities for moral sympathy. “As peoples become more like one another,” Tocqueville remarks, “they show themselves reciprocally more compassionate regarding their miseries, and the law of nations becomes milder” (II.iii.1 [539]).

This transformation of morality has had different but profound effects. It has certainly made people gentler and more civil toward one another. Torture, deliberate cruelty, and spectacles of pain and humiliation that were once so much a part of everyday life have been largely eliminated from the world. Just think of the torture and execution of Damien so graphically described in the opening pages of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, or of William Wallace in the film Braveheart, to get a sense of how far we have moved from the world of the ancien régime.11 We more readily identify with those in pain or those who are suffering, even in distant parts of the world. Consider our responses to victims of the tsunami in Indonesia or to the genocide in Darfur. All of these events affecting people and places where we may never go have a claim on our moral sympathies. President Bill Clinton profoundly captured this point of view when he told his audiences, “I feel your pain”; when George W. Bush was running for president he referred to himself as a “compassionate conservative.” Compassion, it seems, is the moral marker of our time.

Tocqueville clearly believes that this represents a moral progress of sorts, especially in our unwillingness to tolerate policies of deliberate cruelty—note his statement that Americans, of all peoples, have almost succeeded in abolishing the death penalty (II.iii.1 [538])—but still, the advance of compassion comes at a price. “In democratic centuries,” Tocqueville writes, “men rarely devote themselves to one another, but they show a general compassion for all members of the human species” (II.iii.1 [538]). This generalized sympathy is genuine but soft; my ability to feel your pain does not require me to do very much about it. Compassion is a rather easy virtue, so to speak. It suggests sensitivity and openness; it implies caring without being judgmental; it is not exactly relativistic, but it refrains from imposing one’s own morals on others.

Does Tocqueville believe that democratic peoples are in danger of becoming too soft, too morally sensitive, and thus incapable of exhibiting the kind of manly virtues of nobility, self-sacrifice, and love of honor that formed the core of the aristocratic moral code? Yes. Compassion is an admirable sentiment and one likely to expand our range of moral sympathies, but there is also a kind of misplaced compassion that Tocqueville fears. Compassion is a virtue, but it carries with it its own form of misuse when, for example, it becomes a standard by which to express our moral superiority. To be accused of “insensitivity” is in many places today, especially college campuses, the worst moral crime imaginable. We must all care—or at least pretend as if we all care—about the plight of others worse off than ourselves. The result is to create new hierarchies of compassion where one’s superiority is demonstrated by a heightened sensitivity and feeling for others. It is precisely the fallacy of misplaced compassion that is at the root of contemporary forms of “political correctness”—who is the most sensitive among us?—and other moral idiocies of our age.

Compassion is not the only psychological trait of the democratic soul. At the core of the democratic character is a profound sense of uneasiness, of anxiety, which Tocqueville designates by the French word inquiétude. The term has been translated sometimes as “restlessness,” sometimes as “restiveness,” to indicate the perpetually dissatisfied character of the democratic soul. The democratic soul, like democracy itself, is never complete but is always a work in progress.

This feeling of perpetual restlessness is usually tied by Tocqueville to the desire for well-being, by which he always understands material well-being. It is the desire for happiness measured in terms of material happiness that is the dominant drive of the democratic soul. Tocqueville brings to his analysis of democratic restiveness something of the aristocrat’s disdain for the acquisition of mere material goods for which other people have had to work their whole lives. Perhaps this more than anything else is what perplexes him about democracy. Democracy meant for Tocqueville predominantly the middle-class or bourgeois democracies made up of people who are constantly in pursuit of some obscure object of desire.

Consider the following passage from a chapter entitled “Why the Americans Show Themselves so Restive in the Midst of Their Well-Being” (II.ii.13):

In the United States, a man carefully builds a dwelling in which to pass his declining years, and he sells it while the roof is being laid; he plants a garden and he rents it out just as he was going to taste its fruits; he clears a field and he leaves to others the care of harvesting its crops. He embraces a profession and quits it. He settles in a place from which he departs soon after so as to take his changing desires elsewhere. Should his private affairs give him some respite, he immediately plunges into the whirlwind of politics. And when toward the end of a year filled with work some leisure still remains to him, he carries his restive curiosity here and there within the vast limits of the United States. He will thus go five hundred leagues in a few days in order better to distract himself from his happiness. Death finally comes, and it stops him before he has grown weary of this useless pursuit of a complete felicity that always flees from him. (II.ii.13 [512]; see also I.ii.9 [271–72])

Tocqueville’s account here of the restlessness of the democratic soul sounds as if it could have come directly out of book 8 of the Republic, where Plato similarly describes democratic life as continually tempted by various curiosities, hobbies, and stimulants of all kinds, making it always more difficult to concentrate on those few things on which our wholeness entirely depends.

Tocqueville writes here with a kind of disdain for a life understood as a constant—and self-defeating—pursuit of happiness. The desire for well-being becomes the right of the democrat, but the more one desires it, the more it eludes one’s grasp. Thus in the sentence after the passage I have just quoted, Tocqueville says: “One is at first astonished to contemplate the singular agitation displayed by so many happy men in the very midst of their abundance” (II.ii.13 [512]).

There is a world of social commentary condensed into these sentences. Tocqueville’s combination of the words “agitation” and “abundance” in the same passage conveys his sense that the pursuit of happiness is more likely to bring frustration and anxiety than satisfaction and repose. He speculates in the same chapter that while in France there are more suicides than in America, in America there is more insanity. He attributes this ceaseless restlessness and anxiety to the virtual obligation to be happy. He notes “the singular melancholy that the inhabitants of democratic lands often display amid their abundance” (II.ii.13 [514]). Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness have become once more the joyless quest for joy.

The third and final aspect of Tocqueville’s democratic psychology is the doctrine of self-interest or “self-interest well understood.” The doctrine of self-interest well understood is the kind of everyday, practical utilitarianism with which we are instinctively familiar when we are told things like “honesty is the best policy.” It seems simple and obvious enough, but it has a complex history. By the time Tocqueville wrote Democracy, theories of self-interest had long been a staple of European moral philosophers. Already in the seventeenth century, the concept of interest was put forward as a kind of talisman by which to explain all kinds of human behavior.12

What work was the concept of self-interest intended to do? In the first place we often think of self-interest in contrast to altruism. Although interest is an inherently self-regarding disposition, altruism is an inherently other-regarding disposition. But at the time that Tocqueville wrote, self-interested behavior was put forward as a comprehensive antonym to behavior motivated by fame, honor, and, above all, glory. While glory was associated with war and warlike pursuits, interest was invariably associated with commerce and peaceful competition. In contrast to the aristocratic concern with fame and glory, interest was regarded as a relatively peaceful or harmless passion leading men to cooperate with one another for the sake of common ends. The pursuit of self-interest also had an unmistakably democratic and egalitarian impulse. It was something everyone could follow, while such things as honor and glory were by their nature unequally available.

Into this debate between honor and self-interest enters Tocqueville. He begins his chapter entitled “How the Americans Combat Individualism by the Doctrine of Self-Interest Well Understood” (II.ii.8) with the following observation: “When the world was led by a few wealthy and powerful individuals, these liked to form for themselves a sublime idea of the duties of man; they were pleased to profess that it is glorious to forget oneself and that it is fitting to do good without self-interest like God himself. This was the official doctrine of the time in the matter of morality. I doubt that men were more virtuous in aristocratic centuries than in others, but it is certain that the beauties of virtue were constantly spoken of; only in secret did they study their utility” (II.ii.8 [500–501]).

Note that Tocqueville adds to the concept of self-interest the modifier “well understood” (bien entendu). What does this add? Self-interest well understood is not the same thing as egoism or what Rousseau called amour propre. It is not the desire to be talked about, to be looked at, to be first in the race of life. Rather, self-interest is connected to the passion for well-being and the desire to improve one’s condition, which remain for Tocqueville important wellsprings of human action. But it is important to remember that these are not the only motives for action. Tocqueville is not a moral or psychological reductionist. He is not saying that all behavior is self-interested, in the way that some economists and political scientists today assert. In the same chapter Tocqueville cites an essay by Montaigne, significantly entitled “Of Glory,” to remind the reader that the desire for fame and honor will always contend with the desire for well-being and happiness as the principal motives of human behavior.

What did Tocqueville hope that this new ethic of self-interest well understood would bring about? First, it is important to note that he was not recommending the doctrine of self-interest as a universal antidote to the older aristocratic ethos of honor and glory. In a later chapter he laments the decline of the older aristocratic codes of honor and chivalry (II.iii.17). By contrast the doctrine of self-interest well understood may not seem lofty, but it is “clear and sure.” It has the characteristics of reliability and predictability. Self-interest is not itself a virtue, but it can form people who are “regulated, temperate, moderate, farsighted, masters of themselves” (II.ii.8 [502]). These are the virtues of the modern democratic republic: safe, predictable, and bourgeois. Such qualities may not be heroic or extraordinary, but they are within the reach of most.

Tocqueville notes, somewhat ambiguously, that of all “philosophical theories” the doctrine of self-interest well understood is “the most appropriate to the needs of men in our time.” He does not regard self-interest as the key to all human behavior. In that case it would simply be a tautology. It is a guarantee against egoism or selfishness; yet it is also a barrier to the excessive love of glory and honor. Like democracy itself, it addresses “the ordinary level of humanity” (II.ii.8 [502–3]).

Democratic Statecraft

What, finally, is the task of statesmanship in a democratic age? Democracy in America is—as mentioned earlier—a work of political education addressed to leaders (or potential leaders) in Tocqueville’s time and the future. The possibilities of statecraft are themselves dependent on what we understand by political science. In the Introduction to the book Tocqueville states in one of his characteristically epigrammatic sentences that “a new political science is needed for a world altogether new” (7). He clearly believes that his political science departs not only from the ancients but also from some of his modern predecessors, like Locke and Rousseau. What, then, is the distinguishing feature of Tocquevillian political science?

Tocqueville’s new political science, I want to suggest, is based on a novel appreciation of the relation between history or historical forces and human agency. Almost any reader of Democracy quickly notes that Tocqueville attributes to history a kind of providential power that we do not find in earlier writers. The immense, centuries-long transition from the aristocratic to the democratic age seems almost to be an act of divine providence. Tocqueville warns his readers that to try to resist this movement would be not only futile but also impious—to go against the will of God, as it were. He no doubt deliberately overstates his case, but he does so to make a point. Our politics are deeply embedded within long structures of human history, the longue durée, that we can do little to alter or escape. We seem to be deeply embedded within these structures that modern political scientists sometimes call “path development.”

Indeed, Tocqueville sometimes writes as a historical or sociological determinist who allows little room for human initiative and individual agency. Words like “fate,” “destiny,” and “tendency” are used frequently throughout his book to underscore the limits of political action. Tocqueville frequently offers predictions on the basis of underlying trends or causes. Much of this seems, again, to deny the role of independent human initiative or statecraft in history. Consider the following passage from Democracy I: “Sometimes after a thousand efforts, the legislator succeeds in exerting an indirect influence on the destiny of nations, and then one celebrates his genius—whereas often the geographical position of the country, about which he can do nothing, a social state that was created without his concurrence, mores and ideas of whose origin he is ignorant, a point of departure unknown to him, impart irresistible movements to society against which he struggles in vain and which carry him along in turn” (I.i.8 [154–55]).

This passage almost seems to be mocking the claims of writers like Plato, Machiavelli, and Rousseau, who saw the ability of a new prince or Legislator to literally found new peoples and institutions. Tocqueville seems to think that the statesman can do relatively little on his own, that he is strongly circumscribed by a host of factors—geographical, social, moral—over which he can exercise little influence. In Tocqueville’s language, these factors impart “irresistible movements” which simply “carry him along.” The statesman is more like a ship’s captain, dependent on the external circumstances that control the fate of the ship. “The legislator,” he continues, “resembles a man who plots his course in the middle of the sea. Thus he can direct the vessel that carries him, but he cannot change its structure, create winds, or prevent the ocean from rising under his feet” (I.i.8 [155]).

Yet if Tocqueville often writes as if the statesman is hemmed in by a host of external circumstances that constrain his powers of initiation, he also strongly opposes all systems of historical determinism that deny the powers of human agency. While he sometimes writes to shame or humble the pretentions of human greatness, he is just as concerned about the tendency toward self-abnegation that denies the role of the individual. He frequently writes as if this is a peculiarity of democratic times, when all people are considered equal, and therefore each is equally powerless to effect anything. Who has not felt this way?

Consider the often-neglected two-page chapter entitled “What Makes the Mind of Democratic Peoples Lean Toward Pantheism” (II.i.7). On the surface this seems like an odd worry. Pantheism today is regarded as a somewhat benign cult of nature worship of the kind often ascribed to American writers like Emerson and Thoreau. Tocqueville, however, looks at pantheism as an all-embracing form of determinism that is in fact fostered by the equality of conditions. It is an illusion peculiar to democratic times that we are governed by large impersonal forces over which we have no control, and a dangerous illusion at that: “As conditions become more equal and each man in particular becomes more like all the others, weaker and smaller, one gets used to no longer viewing citizens so as to consider only the people; one forgets individuals so as to think only of the species.… I shall have no trouble concluding that such a system, although it destroys human individuality, or rather because it destroys it, will have secret charms for men who live in democracy” (II.i.7 [426]).

Tocqueville returns to this theme fifty pages or so later in a chapter entitled “On Some Tendencies Particular to Historians in Democratic Times” (II.i.20). Here he observes that if ancient historians—think here of Herodotus, Thucydides, Livy—made all events dependent on the actions and dispositions of a few great individuals, modern historians (today we would call them social scientists) do precisely the reverse—they deny altogether the role of the individual in history:

Historians who live in democratic times not only deny to a few citizens the power to act on the destiny of a people, they also take away from peoples themselves the ability to modify their own fate, and they subject them either to an inflexible providence or to a sort of blind fatality. According to them, each nation is invincibly attached, by its position, its origin, its antecedents, its nature, to a certain destiny that all its efforts cannot change. They render generations interdependent on one another, and thus going back from age to age and from necessary events to necessary events up to the origin of the world, they make a tight and immense chain that envelopes the whole human race and binds it. (II.i.20 [471–72])

Note that Tocqueville considers this conception of history a peculiarity of historians in democratic ages. It is not necessarily true. But—and here is Tocqueville’s point—it will become true if we continue to think of it as such. There is a self-fulfilling element to these theories of historical necessity. It is a doctrine that must be resisted, if only because the future of human freedom may be at stake. “I shall say,” Tocqueville continues, “that such a doctrine is particularly dangerous in the period we are in; our contemporaries are only too inclined to doubt free will because each of them feels himself limited on all sides by his weakness, but they will still willingly grant force and independence to men united in a social body. One must guard against this idea, for it is a question of elevating souls and not completing their prostration” (II.i.20 [472]). In other words, the kind of history or political science we adopt is always a kind of moral choice; it will determine to some degree what kind of people we are, whether dependent or free.

Tocqueville is certainly correct in his evaluation of his contemporaries. His was the age of different schemes of historical determinism. Marx was simply the best known of the socialist thinkers who offered a sweeping view of all history as determined by economic factors and class struggle. No less important was the emerging doctrine, just beginning to be enunciated by Tocqueville’s contemporary Arthur de Gobineau, that all history is governed by racial genetics. It is worth noting that Tocqueville carried out a lengthy but respectful correspondence with Gobineau in which he vehemently resists Gobineau’s reductionism that regards all differences between peoples and nations as reducible to racial (including ethnic) features.13

Tocqueville certainly did not discount the importance of race as a factor in history. The longest chapter in either volume of Democracy is called “Some Considerations on the Present State and the Probable Future of the Three Races That Inhabit the Territory of the United States,” where he discusses whites, blacks, and native Americans (I.ii.10 [302–96]). But for Tocqueville race was merely one factor in social explanation. If history is a science—and Tocqueville believes it is—it is not a science that requires a single all-determining cause, whether class, race, or (as might be added today) gender. History is characterized by complexity; there are many sources of causation—physical causes, moral causes, ideas, and sentiments. All of these may be sources of historical change. What Tocqueville wants to resist is the spirit of a system that would reduce all of these to a single factor.

So what, then, is Tocqueville’s teaching, and more specifically what is his advice for the statecraft of the future? Tocqueville is walking a very narrow tightrope. He wishes to convince his contemporaries that the democratic age is upon us, that the transition from aristocracy to democracy is irreversible, and that what he calls the “democratic revolution” is an accomplished fact. Yet, at the same time, he wants to instruct us that what form democracy takes will very much depend on will, intelligence—what he often calls “enlightenment”—and individual human agency. Democracy may be inevitable, but democracy is not all of a piece. It depends not just on impersonal historical forces but also on active virtue and intelligence, ranging from self-interest well understood to ambition and honor. Democracy can still take many forms, and whether it will favor liberty or some kind of collectivist tyranny is very much an open question.

Tocqueville returns to this theme in the final paragraphs of his book. “I am not unaware,” he writes, “that several of my contemporaries have thought that peoples are never masters of themselves here below, and that they necessarily obey I do not know which insurmountable and unintelligent force born of previous events, the race, the soil, or the climate. Those are false and cowardly doctrines that can never produce any but weak men and pusillanimous nations.” And yet he continues: “Providence has not created the human race either entirely independent or perfectly slave. It traces, it is true, a fatal circle around each man that he cannot leave; but within its vast limits man is powerful and free; so too with peoples” (II.iv.8 [675–76]).

Tocqueville leaves us not with a solution but with a paradox or, more precisely, a challenge. We are determined, but not altogether so. The statesman must know how to navigate the shoals between the historical, social, and cultural forces over which we have no say, and the matters of institutional design and moral suasion that are within our power. Politics, as intelligent people have always known, is a medium that takes place within language; it is a matter of providing people with the linguistic and rhetorical abilities both to construct their past and imagine their future. It is language that gives us a latitude, an ability, to adapt to changing circumstances and create new ones. Tocqueville provides us living in a democratic age with the language to shape the democratic statecraft of the future. What we do with that language, how we apply it to new circumstances and conditions that Tocqueville could never have imagined, will be entirely up to us.