CHAPTER 4

Plato on Justice and the Human Good

Marble bust of Plato, 428–348 B.C.E. Photo credit: The Art Archive / Capitoline Museums, Rome / Collection Dagli Orti / Art Resource, NY

The Republic is the book that started it all. Every other work of philosophy is a reply to the Republic, beginning with Aristotle’s Politics and extending up to our own day with John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice. The first and most obvious thing to note about the Republic is that it is a long book, not Plato’s longest work, but long enough. It will not reveal its meaning on a first reading, perhaps not even on a tenth reading unless it is approached in the proper manner with the proper questions. So we must ask, what is the Republic about?1

This is a question that has divided readers of the Republic almost from the beginning. Is it a book about justice as the subtitle of the work suggests? Is it a book about moral psychology and the right ordering of the human soul? Is it a book about the power of poetry and myth? Or is it about metaphysics and the ultimate structure of Being? It is about all of these things—and some others as well—but at least at the beginning we should stay at the surface. The surface of the Republic reveals that it is a dialogue, a conversation. We should approach the book not as we would an analytical treatise but as we might approach a work of literature. It is a work comparable in scope to other literary masterworks, like Hamlet, Don Quixote, War and Peace. As a conversation, it is something that the author wants us to join, to take part in. We are invited to become not passive onlookers but active participants in the conversation that takes place in the book over the course of a single evening. Perhaps the best way to approach the book is to read it aloud as you might a play to yourself or with your friends.

The republic that Plato presents is a utopia (a word not coined until much later by Sir Thomas More). Plato was an extremist. He presents an extreme vision of the polis. The guiding thread of the book is the correspondence between the parts of the city and the parts of the soul. Discord both within the city and within the soul is regarded as the greatest evil. The aim of the Republic is to establish a harmonious city based on a conception of justice that harmonizes the individual and society. The best city will necessarily be one that seeks to produce the best or highest type of individual. Plato’s famous answer to this question is that the city—any city—will never be free from factional discord until kings become philosophers and philosophers, kings (473d).

Many of the debates about the Republic return to the idea of the philosopher-king. Is it intended as a serious proposal for political reform, or did it represent a satire on political radicalism?2 Fortunately, Plato provides a partial solution to this puzzle. In his old age, approximately fifty years after the trial of Socrates and after his abortive Syracusan expeditions, Plato wrote a letter describing at considerable length his disillusionment with politics and returning to the idea of the philosopher-king that he had formed many years before. Here is what he says in the famous Seventh Letter:

When I was a young man I had the same ambition as many others: I thought of entering public life as soon as I came of age. And certain happenings in public affairs favored me, as follows. The constitution we then had, being anathema to many, was overthrown; and a new government was set up consisting of fifty-one men … with absolute powers. Some of these men happened to be relatives and acquaintances of mine, and they invited me to join them at once in what seemed to be a proper undertaking. My attitude toward them is not surprising because I was young. I thought that they were going to lead the city out of the unjust life she had been living and establish her in the path of justice, so that I watched them eagerly to see what they would do. But as I watched them they showed in a short time they made the previous democracy seem like a golden age.

The more I reflected upon what was happening, upon what kind of men were active in politics, and upon the state of our laws and customs, and the older I grew, the more I realized how difficult it is to manage a city’s affairs rightly. For I saw it was impossible to do anything without friends and loyal followers; and to find such men ready to hand would be a piece of sheer good luck, since our city was no longer guided by the customs and practices of our fathers, while to train up new ones was anything but easy. And the corruption of our written laws and our customs was proceeding at such amazing speed that whereas at first I had been full of zeal for public life, when I noted these changes and saw how unstable everything was, I became in the end dizzy.… At last I came to the conclusion that all existing states are badly governed and the condition of their laws practically incurable, without some miraculous remedy and the assistance of fortune; and I was forced to say, in praise of true philosophy, that from her height alone was it possible to discern what the nature of justice is, either in the state or in the individual, and that the ills of the human race would never end until either those who are sincerely and truly lovers of wisdom come into political power, or the rulers of our cities, by the grace of God, learn true philosophy.3

This autobiography provides a kind of introduction to the Republic. Here we have in Plato’s own words the way he viewed politics and his reasons for his political philosophy. Yet if the older Plato looked back with a kind of comprehensive despair and disillusionment with the prospects of reform, the Republic recalls an earlier and happier moment in Plato’s life and the life of his city. The action of the dialogue takes place long before the defeat of Athens, before the rise of the Thirty, and the execution of Socrates, but in the period that Plato refers to in the letter as a “golden age” where perhaps many things seemed possible.

The Republic asks us to consider seriously what would be the look or form of a city ruled both by and for philosophers. In this respect it is the perfect bookend to Plato’s Apology. While the Apology viewed the dangers posed to philosophy and the philosophical life from the city, the Republic asks what a city would look like ruled by philosophy. What would it be like for philosophers to rule? Such a city would require—so Socrates tells us—the severe censorship of poetry and theology, the abolition of private property and the family, at least among the guards, and the use of selected lies and myths—what today would be called “ideology”—as tools of political rule.

Much of modern political philosophy is directed against Plato’s legacy. The modern state is based on the separation of civil society—the entire domain of private life—from the state. Plato’s Republic recognizes no such independent private sphere and for this reason has been thought by some readers to be a harbinger of totalitarianism or fascism. A famous professor at a distant university used to begin his lectures on the Republic by saying, “Now we will consider Plato the fascist.” This was the view of perhaps the most influential book written about Plato during the last century: Karl Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies, which accused Plato of establishing a totalitarian dictatorship along the lines of Stalin’s Russia and Hitler’s Germany.4

But Plato’s Republic is a republic of a special kind. It is not a regime like ours, devoted to maximizing individual liberties, but one that holds the education of its members as its highest duty. His Republic, like the Greek polis itself, was a tutelary association, and its principal good was the education of citizens for positions of public leadership and high statesmanship. Plato, it is good to remember, was a teacher. He was the founder of the first university in the Western world, the Academy. This in turn spawned other philosophical schools throughout the Greek and later the Roman worlds. With the demise of Rome in the early Christian centuries, the philosophical academies were transformed into the medieval monasteries, and these in turn became the basis of the first universities in places like Bologna, Paris, and Oxford. When these were transplanted to the New World to places like Cambridge and New Haven, we can say today without doubt that we are literally the inheritors of the Platonic Republic. We are the heirs of Plato. Without him, no Yale.

And in fact the institutional and educational requirements of the Republic share many features with a place like Yale. In both places men and women are selected from a relatively early age because of their capacities for leadership, courage, self-discipline, and responsibility; they spend several years living together, eating in common mess halls, exercising, and studying far from the oversight of their parents. The best of them are winnowed out to pursue further study and eventually assume positions of high public authority. Throughout, they are subjected to a course of rigorous study and physical training that will lead them to adopt prominent positions in the military and other branches of public service. Does this sound at all familiar? It should. If Plato is a fascist, I would ask, what then are you?

Plato is an extremist, and he often pushes some of these ideas to their most radical conclusion, but he is defining a kind of school. He regards the politeia or republic as a school whose chief goal is preparing students for the guidance and leadership of a community. No less an authority than Jean-Jacques Rousseau understood this in its deepest sense: “Do you want to get an idea of public education?” Rousseau wrote in his Emile. “Read Plato’s Republic. It is not at all a political work, as think those who judge books only by their titles. It is the most beautiful educational treatise ever written.”5

“I went down to the Piraeus”

“I went down” or in Greek, katēben. These first words of the Republic are not merely incidental. I heard a story that when the German philosopher Martin Heidegger taught the Republic he never got beyond the opening lines. Socrates’s descent to the Piraeus is a katabasis, a going down, modeled on Odysseus’s descent to Hades in the Odyssey. The work is a kind of philosophical Odyssey that both imitates Homer and anticipates other odysseys of the mind, like those of Cervantes or Joyce. The book is full of a number of descents and corresponding ascents, like the climb up the Divided Line to the world of the imperishable Forms late in the book, only to return to the underworld in the Myth of Er at the very end. The work is written not only as a timeless philosophical treatise but as a dramatic dialogue with a setting, a cast of characters, and a firm location in time and place.

The action of the dialogue begins at the Piraeus, the port of Athens, sometime around 421 B.C.E. during the so-called Peace of Nicias when there was a truce in the war between Athens and Sparta. At the beginning we see Socrates and his friend Glaucon trolling the waterfront, so to speak. What are they doing? Why are they together? What do they see in one another? These are questions that immediately come to mind. We learn shortly after that they had gone down to the Piraeus to view a festival where a new goddess was being introduced. The suggestion is that it is the Athenians—not Socrates—who introduce new deities. Socrates’s remark that the Thracians put on quite a show suggests that his own perspective is not bound by his own city. It suggests a loftiness and impartiality characteristic of a philosopher, but not of a citizen.

On their way back to town they are accosted by a slave who has been sent on by Polemarchus and his friends, who order Socrates and Glaucon to wait up. “Polemarchus orders you to wait,” the slave says. “He is coming up behind you,” he continues, “just wait.” “Of course we’ll wait,” Glaucon replies. When Polemarchus and his friends arrive—friends who include Adeimantus, the brother of Glaucon, and Niceratus, the son of the famous general Nicias, whose brokered peace they are now enjoying—they challenge Socrates to stay with them or prove stronger. “Could we not persuade you?” Socrates asks. Not if we won’t listen, Polemarchus replies. Instead a compromise is reached. Let Socrates and Glaucon come with Polemarchus and the others to the home of Polemarchus’s father, where a dinner will be provided, and later return to the festival, where a horserace will take place. “It seems we must stay,” Glaucon acquiesces, and Socrates concurs (328b).

This opening gambit sets the stage for much of what is to follow. The issue is, who has title to rule? Is it Polemarchus and his friends, who claim to rule by the strength of numbers alone, or Socrates and Glaucon, who hope to rule by the powers of reasoned speech and persuasion? Can democracy, which expresses the will of the majority, be rendered compatible with the needs of philosophy that claims to respect only reason and the better argument? Or can a compromise between the two be reached? Is the just city a combination of the two, of force and persuasion?

The Faces of Justice

The first book of the Republic is a preamble for what follows. Here we see Socrates carry on a number of conversations, no doubt of the kind for which he became famous and for which he was subsequently tried and executed. As in any Platonic dialogue it is important to look not just at what is said but at what Plato chooses to reveal about the particular individuals with whom Socrates speaks. It is not only the words but also the action of the dialogue that counts. Who are Socrates’s interlocutors? What do they represent? There is Cephalus, the venerable father of the family, Polemarchus his son, a solid patriot who defends not only his father’s honor but also that of his friends and fellow citizens, and Thrasymachus, a cynical intellectual who rivals Socrates as an educator of future leaders and statesmen.

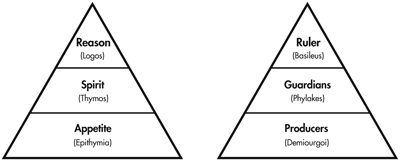

There is in the dialogue a distinct hierarchy of characters who, we see later on, express certain distinctive features of both the soul and the city. Cephalus, we learn, has spent his life in the acquisitive arts, concerned with satisfying the needs of his body; he represents the appetitive soul. Polemarchus—whose name means War Lord—is preoccupied with questions of honor and loyalty; he represents the spirited part of the soul. And Thrasymachus, a visiting sophist, seeks to teach and educate, anticipating what the Republic calls the rational soul. Each of these characters serves to prefigure the relatively superior natures of those who come later in the dialogue. The two brothers, the hedonistic and pleasure-seeking Adeimantus, the fierce and warlike Glaucon, and of course the philosophically minded Socrates each embody one of the key components of the soul—appetite, spiritedness, and reason. Together these figures form a kind of microcosm of humanity. Each of the participants in the dialogue represents one of the specific classes or groups that will eventually occupy the just city, to which Socrates will give the name Kallipolis.

We do not need to interrogate at length the arguments that Socrates makes against each of his interlocutors. Most important is what they stand for. Cephalus represents the claims of age, tradition, and the family. At the beginning of the dialogue, he has just returned from performing certain ritual sacrifices to the gods. His place as head of the household supported by wealth and the authority that wealth confers makes him the natural lead-off batter. Cephalus initially expresses great joy at seeing Socrates but is abruptly challenged by him with the question what it is like to be so old, to which Socrates then adds insult to injury by asking whether Cephalus’s reputation for justice is not merely a consequence of his great wealth. Cephalus then tells Socrates how his advanced age has freed him from the erotic passions that had occupied his youth, that when he was not engaged in or thinking about sex, he devoted his life to increasing his fortune. He recalls a line from Sophocles, who was asked whether he could still enjoy sex in his old age. “Silence, man,” the poet replied. “Most joyfully did I escape it as though I had run away from a kind of frenzied and savage master” (329c). Now in the twilight of his years he is able to turn his attention to justice, that is, performing sacrifices commanded by the gods. Why does Plato begin here?

Cephalus is the very embodiment of the conventional. He is not a bad man, but a thoroughly unreflective one. In attacking Cephalus, Socrates attacks the embodiment of the conventional opinions supporting the city. Note that Socrates turns Cephalus’s statement that the pious man practices justice by sacrificing to the gods into the proposition that justice means paying one’s debts and returning what is owed. This sleight of hand, which Socrates then turns against Cephalus—What do you think about returning a borrowed weapon to a madman?—has the effect of pushing Cephalus out of the conversation for good. Socrates achieves his desired effect. He banishes the natural head of the household in the same way that he will later try to abolish the family and property from Kallipolis. Socrates asserts his claim to rule over and above the claims of traditional authority.

Socrates next pursues the conversation with Polemarchus, the self-professed “heir” of the argument as well as to the family fortune. Polemarchus is what the Greeks would call a gentleman or Kalosgathos—a person willing to stand up for and defend his family and friends. Unlike his father, who shows himself concerned with the needs of the body (wealth and sex), Polemarchus is concerned to defend the honor and safety of the polis. He accepts the view of justice as giving to each what is owed, but interprets this to mean doing good to your friends and harm to enemies. Justice is, then, a kind of loyalty that we feel to family, members of a team, fellow students of a residential college, or to Yale as opposed to all other places. It is the kind of patriotic sentiment that citizens of one country feel for one another in opposition to all other places. Justice is a devotion to the good of one’s own family, friends, and citizens.

Socrates challenges Polemarchus on the grounds that loyalty to a group cannot be a virtue in itself. Do we ever make mistakes? he asks Polemarchus. Isn’t the distinction between friend and enemy based on a kind of knowledge? If so, haven’t we ever mistaken friend for enemy? How can we say that justice means helping friends and harming enemies when we may not even know with certainty who our friends and enemies really are? Why should the citizens of one state, namely our own, have any moral priority over the citizens of another state? Isn’t such an unreflective attachment to our own bound to result in injustice to others? Once again we see Socrates dissolving the bonds of the familiar. At no other point in the Republic do we see so clearly the tension between philosophical reflectiveness and the sense of comaraderie, mutuality, and esprit de corps necessary for political life.

Polemarchus appears to believe that a polity can only survive with a vivid sense of what it is and what it stands for and an equally vivid sense of what it is not and who its enemies are. Socrates challenges the very possibility of political life by questioning our ability to distinguish friend from enemy. Although Polemarchus is reduced to silence, it is notable that his argument is not defeated. Later in the Republic Socrates will argue that while the best city will be characterized by peace and harmony, this will never be the case in relations between cities. This is why even the best city, even Kallipolis, will require a warrior class. War and the preparation for war will be an intrinsic part of the just city. Even the Platonically just city will have to cultivate a “noble lie” to convince its citizens that there is a difference in nature between them and citizens of other states (414c–415d).

Thrasymachus presents the most difficult challenge to Socrates, in part because he is Socrates’s alter ego. Thrasymachus is a rival to Socrates as an educator and teacher. Unlike the others, he claims to have knowledge of what justice is and is willing to teach it for a price. His teaching is presented in the language of hard-boiled realism—he professes disgust at Polemarchus’s and Socrates’s lofty discussions of loyalty, friendship, and conferring benefits on others. Justice, he claims, is the interest of the stronger. Every polity, he argues, is based upon a distinction between the rulers and the ruled. Justice consists of the rules that are made for the benefit of the ruling class. It is nothing more—and nothing less—than the self-interest of the stronger party (338c).

Thrasymachus is the kind of “intellectual” who enjoys bringing the harsh and unremitting facts about human nature to light. No matter how much we might dislike Thrasymachus, we all feel there is more than a grain of truth in what he says. He contends that man is a being who is first and foremost dominated by a desire for power. This is what distinguishes the true man or the real man from the slave. Power and domination are what we care about most. What is true of individuals is also true for states. Every polity seeks its own advantage against others, making relations between states an unremitting war of all against all. Politics, in the language of modern game theory, is a zero-sum game. There are winners and losers. The rules of justice are simply the laws set up by the winners to protect their own interests.

Socrates challenges Thrasymachus with a version of the argument that he used against Polemarchus. Do we ever make mistakes? he asks. That is, if justice is the interest of the stronger, doesn’t it require some kind of knowledge to know what it is in our interest to do? Interests are not brute facts but require reflection. We frequently distinguish our true or long-term interests (“enlightened self-interest”) from short-term gains and immediate gratification. What it is in our interest to do or to be is not always self-evident. Do we ever mistake what is in our interests? Of course we do, Thrasymachus cannot help but admit. So justice cannot be simply power, it is power in conjunction with knowledge. We are close to the famous Platonic thesis that all virtue is knowledge.

Most of the exchange with Thrasymachus turns on the problem of what kind of knowledge justice involves. Thrasymachus contends that justice consists in the art of convincing people to obey rules that are really in the interests of the rulers. Justice is based on a kind of elaborate deception. We obey the rules of justice because we fear the consequences of injustice. The true man or real man would be the one with the courage to act unjustly for his own interests. The true ruler is one who treats his subjects like a shepherd treats his flock, that is, not for the good of the sheep but for the good of the shepherd. All rule, like all justice, is based on self-interest. Is Thrasymachus wrong to believe this?

Socrates wins his argument with a sleight of hand. Both he and Thrasymachus believe that justice is a virtue, but what kind of virtue can it be to deceive and fleece people? Thrasymachus is forced to admit that the just person is a fool for obeying laws that are not beneficial to him, while the best life is one of perfect injustice, doing whatever you want whenever you want. With this realization Thrasymachus begins to blush with embarrassment (350d). Why does Thrasymachus blush? Why should he be embarrassed to defend the unjust life? Apparently, he is not as tough as he thinks. He reveals himself to be far more conventional than his bold and ruthless words would seem to admit.

Book 1 ends in uncertainty with the three arguments of Cephalus, Polemarchus, and Thrasymachus having been silenced, but as yet no clear alternative to put in their place. It is only now that the real action of the dialogue can begin.

Glaucon and Adeimantus

Book 1 is a kind of warm-up for what follows in the rest of the Republic. In the first book we see Socrates refute—or appear to refute—a number of views of justice, yet we have no better idea of what justice is than we did at the beginning. Until we know this, there is little reason for us to abandon our previous ideas. It is here where Glaucon intervenes.

Glaucon tells Socrates that he is dissatisfied with his refutation of Thrasymachus—and so should we be. Thrasymachus has been shamed (he blushes), but not refuted. Glaucon tells Socrates that it is not enough to show that injustice is wrong; what we need is to hear the case for why justice is good or, more precisely, he wants to hear justice praised “for itself.” “Is there in your opinion,” he challenges Socrates, “a kind of good that we would choose because we delight in it for its own sake?” (358a). This is where the rubber hits the road.

Before addressing Glaucon’s challenge we might ask who he is. Glaucon and his brother, Adeimantus, are the brothers of Plato. Other than their appearance in the Republic there is no historical record left of either of them, but Plato has given us enough. In the first place, they are young aristocrats, and Glaucon’s desire to hear justice praised “for its own sake” indicates his scale of values. It would be vulgar to speak of justice or any virtue in terms of material rewards or consequences. Glaucon does not need to hear justice praised for its benefits. Rather, he complains that he has never heard justice defended the way it ought to be. The brothers’ desire to hear justice praised for itself alone is expressive of their freedom from utilitarian or mercenary motives; it reveals a kind of idealism and loftiness of soul not present in any of the previous interlocutors.

Certainly the brothers are not slouches. Although their role later in the dialogue may be reduced to repeating “Yes, Socrates” and “No, Socrates,” their early challenges show them to be potential philosophers, the kind of persons who might one day rule the city. Of the two, Glaucon is clearly the superior. He is described as “most courageous,” which in the context means most manly and virile. Later Socrates admits that he has “always been full of wonder at the nature” of the brothers and goes on to cite a line of poetry written about them after they had distinguished themselves in battle (368a).

They are also highly competitive super-achievers—something like yourselves. There is quite a bit of jousting between them that one needs to be attentive to. Each proposes to Socrates a test that he will have to pass in order to prove the value of justice and the just life. Glaucon goes on to rehabilitate Thrasymachus’s argument about the unjust life, but presents it more vividly than Thrasymachus could do himself. Glaucon tells the story of Gyges, who possessed a magic ring that conferred on him the power of invisibility.6 Who has not wondered what we would do if we had this power? Gyges murders the king and sleeps with his wife. What would you do? In any case, Glaucon wants to hear why a man with the power of Gyges should wish to be just. If we could commit any crime, indulge any vice, commit any outrage and be sure that we could get away with it, why would we want to be just? That is the challenge Glaucon poses to Socrates. Why would someone with absolute power and complete immunity from the law prefer justice to injustice? If justice is something truly worthy, then Socrates should be able to convince Gyges that it is in his interest to be just. This is certainly a tall order.

Now Adeimantus chimes in. He has heard parents and poets praise justice for its benefits in this life and the next. He takes this to mean that justice is a virtue for the weak, lame, and unadventurous, that is, justice is presented as good because of the consequences that will attend it. A real man does not fear the consequences of injustice. His concern, Adeimantus tells us in a revealing image, is with self-guardianship or self-control: “each would be his own guard” (367a). In other words we should not care what people say about us but instead we should be prepared to develop qualities of self-containment, autonomy, and independence from the influence that others can exercise over us. If justice is worth pursuing, then it is worth pursuing for its sake alone, not for some putative advantages or disadvantages that might follow.

The two brothers’ desire to hear justice praised for itself (Glaucon) and to live freely and independently (Adeimantus) shows to some degree their distance from their own society. To put the case slightly anachronistically: these two are sons of the aristocracy who feel degraded by the mendacity and hypocrisy of the world around them. What person with any sensitivity has not felt this way at one time or another? The two are open to persuasion to consider alternatives—perhaps radical alternatives—to the society that nurtured them. They are potential revolutionaries. The remainder of the Republic is addressed to them and people like them.

City and Soul

With the speeches of Glaucon and Adeimantus, the circle around Socrates has effectively closed. Socrates knows that he will not be returning to Athens that evening. He proposes instead a kind of thought experiment that he hopes will work magic on the two brothers. Let us, he proposes, “watch a city coming into being in speech” (369a). Rather than considering justice microscopically in an individual through a magnifying glass, let us view justice in a city in order to help us better understand what justice is in an individual.

This idea that the city is essentially analogous to the soul is the central metaphor around which the entire Republic turns. It is introduced quite innocuously, and no one in the dialogue objects, yet everything else follows from this idea that the city is in its essential aspects like an individual, and vice versa. What is Socrates trying to do here, and what function does the city-soul analogy serve?

To state the obvious: Socrates introduces the analogy to help the brothers better understand what justice is in an individual or in the soul, to use the proper Platonic term. The governance of the soul—Adeimantus’s standard of self-control—must be like the governance of the city in some decisive respects. But how is a city like a soul, and in what respect is self-governance like governing a collective entity like a polis?

Consider what we mean when we say that someone is “typically American” or that someone else is “typically French.” We take it to mean that their character and behavior expresses certain traits that we have come to regard as representative of a cross-section of their countrymen. Is this a useful way to think and speak? More specifically, what does it mean to say that an individual can be seen as magnified in his or her country or that one’s country is simply the collective expression of certain individual character traits?

One way of thinking about this thesis is to regard it as a particular causal hypothesis about the formation of both individual character and political institutions. This reading of the city-soul analogy grows out of the view that, as individuals, we live in societies that both shape us and that we help to shape in turn. The city-soul analogy is an attempt to understand how societies reproduce themselves and shape citizens who in turn help the society in question to function.

This is helpful, but it still makes us think. In what ways are cities like individuals? Does it mean that something like the presidency, the Congress, and the Supreme Court can be discerned within the soul of every American citizen? This would clearly be absurd. Or does it mean that American democracy helps to produce a particular kind of democratic soul, just as the old regime in France tended to produce a certain kind of aristocratic character. Every regime will produce a distinctive kind of individual, and this individual will come to embody the dominant traits of character of the regime.

The remainder of the Republic is devoted to crafting a regime that will produce a certain distinctive character type. This is why Plato’s republic is properly called a utopia. There has never been a regime in history that was so single-mindedly devoted to this end, to produce this rarest and most difficult species of humanity, namely, the philosopher.

The Reform of Poetry

Socrates’s “city in speech” proceeds through various stages. The first stage, proposed by Adeimantus, is the simple city, the “city of utmost necessity,” that is, a city limited to the satisfaction of certain basic needs. This primitive or simple city expresses the nature of Adeimantus’s soul. There is a kind of noble simplicity that treats its subjects as pure bodies or creatures of limited appetites. The simple city is little more than a combination of households designed for the purpose of securing existence.

At this point Glaucon retorts that it seems as if his brother has created a “city of pigs” (372d). Where are the luxuries? Where are the “relishes,” he asks? Where are the things that make up a city? Glaucon’s city in turn expresses his soul. The warlike Glaucon would preside over a “feverish city,” as it is called, one that institutionalizes honors, competition, and above all war. If Adeimantus expresses the appetitive part of the soul, Glaucon represents spiritedness, or what Plato calls thymos. Thymos is the central psychological category of the Republic. Spiritedness is that quality of soul that is most closely associated with the desire for honor, fame, and prestige. It is what seeks distinction, the desire to be first in the race of life, to lead and dominate others. It is the quality we associate with the alpha male. The issue for Socrates is how to channel thymos from a wild and untamed passion into support for the city and the common good. Can this be done? How would one begin the domestication of the thymotic soul? The entire thrust of the book is devoted to the taming of spiritedness.

It is here where Socrates turns to his first and one of his most controversial proposals. The creation of a just city—and not merely Glaucon’s luxurious city—can only begin with the control of poetry and music. It is from this that the image of Plato as educator derives. The first order of business for the founder of a city is the oversight of education. It is the principal task of a lawgiver to control what kinds of stories, histories, drama, poetry, and music people are permitted to hear and see. His proposals for the reform of poetry, especially Homeric poetry, represent a radical departure from Greek educational practices and beliefs. Why is this so important?

In the first place, it is from the poets in the broadest sense of the term—mythmakers, storytellers, artists, and musicians—that we receive our earliest and most vivid impressions of heroes and villains, gods and the afterlife. These stories shape us for the rest of our lives. The Homeric epics were to the Greek world what the Bible has been for ours. The names of Achilles, Priam, Hector, Odysseus, and Ajax would have been as familiar to the Greeks as the names and stories of Abraham, Isaac, Joshua, and Jesus are to us.

Plato’s critique of Homeric poetry is twofold: theological and political. The theological critique is that Homer depicts his gods as fickle and inconstant; such beings cannot be worthy of true worship. But more important, the Homeric heroes are said to be simply bad role models. They are shown to be intemperate in sex and unduly fond of money. To these vices Socrates adds excessive cruelty and disregard for the dead bodies of one’s opponents. The Homeric heroes are ignorant and passionate men, full of blind anger and the furious desire for retribution. How could such figures possibly serve as positive models for the future citizens of Kallipolis?

Socrates’s answer is, of course, the complete purgation of poetry and the arts. He wants to deprive the poets of their power to enchant and bewitch, something to which Socrates admits later he has always been susceptible (607c). In place of the pedagogical power of poetry, Socrates proposes to install philosophy. Consequently, the poets will have to be expelled from the just city.

Is Socrates’s censorship of poetry and the arts an indication of his totalitarian impulse? This is the part of the Republic most likely to call up our First Amendment instincts. Who are you, Socrates, we want to ask, to tell us what we can read, hear, and listen to? Furthermore, Socrates is not saying that Kallipolis would have no poetry and music; it would simply have to be Socratic poetry and music. But what would such Socratically purified poetry and music look or sound like? I do not have an answer to this. Perhaps the Republic as a whole is a piece of Socratic poetry.

It is important to remember that the question of education is introduced in the context of taming the warlike passions of Glaucon and others like him, whom Socrates refers to as the Auxiliaries of the city. The question of censorship and telling of lies is introduced not as an aesthetic matter but as a matter of military necessity. Nothing at all is said about the education of farmers, artisans, merchants, and laborers. To speak bluntly, Socrates does not care about them. Nor has he said anything yet about the education of the philosopher. His interest here is in the creation of a tight and highly disciplined cadre of young warriors who will protect the city much as watchdogs protect their homes (376a). Such individuals will subordinate their own desires and satisfactions to the group and live by a strict code of honor.

Are Socrates’s proposals unrealistic? Undesirable? Not if you believe, as he does, that even the best city must make provisions for war and therefore a warrior class. Such a life—the soldier’s life—requires harsh privations in terms of material rewards and benefits as well as a willingness to die for others, fellow citizens to be sure, but people whom they will not even know. Far more unrealistic would be those who believe that we can one day abolish war and the passions that give rise to it. So far as the passionate or spirited aspect of human nature remains strong, Plato believes, so long will it be necessary to attend to the warriors of society.

The Soul of the Guards

The great theme of the Republic—at least one of the great themes—is the control of the passions. Of course, this is the theme of every great moralist from Spinoza to Kant to Freud. How do we control the passions? Every moralist has a strategy for helping us to submit our passions to the control of reason or some kind of supervening moral power. Recall that this is the problem raised at the beginning of book 2 by Adeimantus, who puts forward an idea of self-control or self-guardianship that essentially entails protecting ourselves from the passion for injustice. Independence means not only freedom from control by others but also an image of self-control, control over our most powerful passions and inclinations.

The most powerful passion is designated by Socrates as thymos. This we have seen is the political passion par excellence. It is the kind of fiery desire for fame and love of distinction that leads men (and women) of a certain type to pursue their ambitions in public life. It is connected to the capacity for heroism and self-sacrifice, but it is also related to the exercise of domination and tyranny over others. The quality of thymos is possessed by every great statesman, but also by every tyrant who has ever lived. The question posed by the Republic is whether this thymotic quality can be controlled, and if it can, can it be put into the service of the public good?

Socrates introduces the problem of thymos with a story. In book 4 he tells a story that he says he has heard and believes: “Leontius, the son of Aglaion, was proceeding up from the Piraeus outside the North wall when he perceived corpses lying near the public executioner. At the same time, he desired to see them and, to the contrary, he felt disgust and turned himself away; and for a while he battled with himself and hid his face. But eventually overpowered by desire he forced his eyes open and rushing toward the corpses said, ‘See you damned wretches! Take your fill of the beautiful sight’ ” (439e).

The story that Socrates tells here is not one of reason controlling the passions but one of intense internal conflict. Leontius is torn by conflicting emotions, both to see and not to see; he is at war with himself. Who has not experienced this situation? Is it not the same emotion we feel when passing a car wreck on a highway? There is something shameful about slowing down to look to see if there is a body on the road, and yet our eyes are compelled to look, often despite ourselves. Think about it. The result is that Leontius becomes angry with himself for wanting to look on something he knows to be shameful. It is his thymos that is the cause of this anger.

The thymos of Leontius is connected to the fact that he is a certain kind of man: proud, independent, someone who wants to be in control of himself (and yet can’t be). His is a soul at war with itself and potentially at war with others. The Republic tries to offer a strategy—perhaps we might even call it a therapy—for dealing with thymos, for submitting it to the control of reason and allowing us to achieve a level of balance, self-control, and moderation. These qualities, taken together, Plato calls justice, which can only be achieved when reason is in control of our appetites and desires. Can such an ideal of justice ever be achieved? Can reason soften and moderate our conflicting emotions and desires? Can the soul of the guardian serve the cause of justice? These questions are addressed by Socrates with his construction of Kallipolis.

The Three Waves

The construction of Kallipolis proceeds through what Socrates calls “three waves.” These waves are, first, the restriction of private property, second, the abolition of the family, and, third, the establishment of the philosopher-king. Each of these waves is regarded as necessary for the proper construction of the just city. I will say something here about the proposals for coeducation of men and women that are a part of Socrates’s plan for the abolition of the family.

The core of Socrates’s proposal is the equal education of men and women, a proposal that in context he presents as laughable knowing it will certainly seem that way to Glaucon and Adeimantus. There is no job, Socrates states, that cannot be performed equally well by both men and women. Gender differences are no more relevant when it comes to positions of rule than is the distinction between the bald and the hairy (454c–d). Socrates is saying not that men and women are the same in every respect but that they are equal with respect to competing for any job at all. There will be no glass ceilings in Kallipolis. Socrates is perhaps the first champion of the emancipation of women from the household.

The proposal for a level playing field demands equal access to education. Here Socrates insists that if education is to be equal, both men and women should be submitted to the same regimen, meaning that they will exercise in the nude among one another in coed gymnasia. Moreover, marriage and procreation are to be for the sake of the city. Accordingly, there must be strict oversight of sexual contact between men and women. There is to be nothing like “romantic love” among the members of the guardian class. Sexual relations are intended strictly for the sake of reproduction, with unwanted fetuses aborted. The only exception to this prohibition is for members of the guardian class who are beyond the age of reproduction; they may have sex with anyone they want (a version of “recreational sex”) as a reward for a lifetime of self-control. Child bearing may be inevitable for the woman, but rearing the child will be the responsibility of the community or at least the class of guardians in common day-care centers. In the language of Hillary Clinton, “It takes a village.” No children should know their biological parents and no parents, their children. The purpose of this scheme is to eliminate the pronouns “me” and “mine,” which should be replaced by “ours.”

The Platonic community is to be one where men and women are rendered as alike as possible, “a community of pleasure and pain” (464a). I am reminded of the story told by the French feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, who expressed a similar point of view about creating a community where the “I” would literally become a “We.” What if I have a pain in my foot, someone objected. “No,” she replied, “we will have a pain in your foot.”7

The objections to Socrates’s—and Beauvoir’s—proposals are obvious. Aristotle was only the first to complain that common ownership, whether of children or property, leads to common neglect. We truly care only about what is ours; the community will never replace the individual as the ultimate locus of our love and concern. This is an old story, but again it is worth remembering that Socrates advances his prescriptions not to create happy or satisfied individuals, but for the sake of creating a unified guardian class capable of protecting and defending the city. The purpose of marriage is, to put it bluntly, to create soldiers.

It is in the same context of his treatment of men and women that, it often goes unnoticed, Socrates proceeds to rewrite the laws of war. In the first place children will be taught the art of war; “this must be the beginning [of their education],” Socrates notes, “making the children spectators of war” (467c). Not only is expulsion from the ranks of the guardians the penalty for cowardice, Socrates suggests that there should be erotic rewards for those who excel in bravery. Consider the following remarkable proposal:

SOCRATES: “But I suppose,” I said, “you wouldn’t go so far as to accept this further opinion.”

GLAUCON: “What?”

SOCRATES: “That he kiss and be kissed by each.”

GLAUCON: “Most of all,” he said. “And I add to the law [of war] that as long as they are on that campaign no one whom he wants to kiss be permitted to refuse, so that if a man happens to love someone, either male or female, he would be more eager to win the rewards of valor.”

SOCRATES: “Fine,” I said. (468b–c)

A rather prudish twentieth-century translator of Plato, Paul Shorey, notes of this proposal: “This is almost the only passage in Plato that one would wish to blot.”8 But just imagine what an incentive such as this might do for military recruitment today!

Justice as Harmony

At long last we are able to come to the theme of the Republic: justice. Recall that the Platonic idea of justice concerns harmony, both harmony in the city and harmony in the soul. We learn that the two are structurally homologous. Justice is variously defined as “what binds [the city] together and makes it one” (426b) and as “minding one’s own business” (433a). Put another way, it consists of everyone and everything performing those functions for which they are best equipped. “Each of the other citizens,” Socrates says, “must be brought to that which naturally suits him—one man, one job—so that each man practicing his own, which is one, will not become many but one, thus, you see, the whole city will naturally grow up to be one” (423d).

At the very least, these passages indicate that it was not Adam Smith but Plato who discovered the division of labor. But while Smith saw how the increased specialization of functions—his famous example was a pin factory—contributed to the overall “wealth of nations,” he was also cognizant of how the division of labor contributed to the narrowing and moral enervation of the worker. The paradox was that while the division of labor contributed to increased prosperity for society, it could also lead to the stultification of the individual. But Plato raises no such objection. For him, the division of labor leads to a concentration of the mind on the one or few activities that give life a sense of wholeness, gravity, and purpose.

The idea here is that justice consists in following a strict division of labor, everyone working at the job or task that naturally fits or suits him or her. One can, of course, raise several objections to this view of justice. Again Aristotle took the lead: Plato’s excessive emphasis on unity destroys the natural diversity of human beings that make up a city. Is there one and only one thing that each person does best and, if so, who is to decide what it is? Will such a plan of justice not be unduly coercive in forcing people into predefined social roles? Shouldn’t individuals be free to choose for themselves their own plans of life wherever these might take them?

However this may be, Plato believes he has found in the formula of the division of labor—one person, one job—a foundation for justice. That is to say, if the three parts of the city—craftsmen, auxiliaries, and guardians—all work together by each attending to his or her own tasks, doing his or her own job, peace and harmony will prevail. And since the city is simply the soul writ large, the three social classes merely express the three parts of the soul. The soul is a just soul when appetite, spiritedness, and reason cooperate, with reason ruling spirit and appetite, just as in the polis the philosopher-king rules the warriors and the craftsmen. The result is a perfect balance of the parts of the whole. The city and the soul each appear as a pyramid rising from a broad and flat base to a peak of perfection something like the following:

But this is to return us to Socrates’s initial proposal. Are the structure of the city and the structure of the soul really identical? Maybe not. For example, every individual necessarily consists of three parts of the soul—appetite, spirit, and reason—yet each of us will be confined to one and only one task in the social hierarchy. Why should a multifaceted being be confined to one social role? I assume what Socrates means is that although every person will embody to some degree all three of these features, only one of them will be the dominant trait in each of us. Some of us are dominantly appetitive, others spirited, and so on. But does even this make sense? The capacity to make money requires not just the appetites but also the powers of foresight and calculation, and a willingness to take risk. The capacity for war requires more than thymos alone; it requires the ability to conceive strategy, to pursue tactics, and to exhibit qualities of leadership and command. To confine the individual to one, and only one, sphere of life seems an injustice to the internal moral and psychological complexity that makes of us who we are.

There are further discrepancies in this analogy between city and soul. Justice in the city consists of each member fulfilling his or her task in the social division of labor. But this is a very far cry from justice in the soul that consists in a kind of rational autonomy or self-control, where reason directs the appetites. In point of fact, very few citizens will live a life of rational mastery and self-control. Most will be consigned to remedial tasks where they will live under the tutelary control of the guards of Kallipolis. The irony is that while the vast majority of citizens may live in a Platonically just city, very few of them will lead Platonically just lives. The only truly just individuals will be the philosophers who live according to reason and who control their passions and appetites. But what of the rest? The harmony and self-discipline of the city will not be due to each of its members; social justice will be the result of a functionally mandated division of labor that will be controlled by the selective use of lies, myths, and various other deceptions. How can a city be just if very few of its citizens are permitted to live just lives?

This question is raised in the Republic by Adeimantus, who at the beginning of book 4 asks Socrates: “What would your apology be Socrates if it were objected that you’re hardly making these men happy?” (419a). Adeimantus is concerned here that Socrates is being unfair to the Guards, giving them all the responsibilities but none of the rewards of political rule. How can a citizen of Kallipolis live a just or a happy life if he or she is deprived of the goods or pleasures that most of us seek? “In founding the city,” Socrates replies, “we are not looking to the exceptional happiness of any one group among us, but that of the city as a whole” (420b). Socrates deliberately suppresses here the definition of justice as self-guardianship or independence for the political definition of justice as collective well-being or collective harmony. Why does he do this? Is such an answer satisfactory? What does such an answer tell us about Socrates?

The fact that neither Adeimantus nor Glaucon disputes Socrates’s answer suggests that they share a common belief that the justice or collective well-being of the city must take precedence over the happiness of the individual. They are not natural ascetics; they desire pleasure, but in the case of a conflict between the happiness of the individual and the happiness of the city they agree that their own interests and desires must take a back seat. But the idea of a conflict between the individual and the city suggests that Kallipolis is not complete. The city-soul analogy proposed in book 2 suggested that a just city would be one where city and soul were in perfect accord, where conflict between the private good of the individual and the public welfare of the city were one and the same. At the least, the task of founding the city is incomplete. It will only be complete, and we will only see justice “coming into being,” with the introduction of the philosopher-king.

The Philosopher

The Platonic republic is not complete until the third and final wave of paradox with the proposal for a philosopher-king. “Unless the philosophers rule as kings or those now called kings and chiefs genuinely philosophize,” Socrates asserts, “there will be no rest from ills for the cities” (473d). Socrates presents this proposal as outlandish. He says that he expects to be “drowned in laughter.” This has led some readers to suggest that Socrates’s proposal for philosopher-kings is ironical, that it is intended as a kind of joke to discredit the idea of a just city or at least to indicate its extreme implausibility. The question is why Socrates regards philosopher-kingship as a requirement for a just polity.

I am by no means sure that Plato did regard the idea of the philosopher-king as an impossibility, much less an absurdity. Plato himself took three arduous trips to Sicily to serve as an adviser to two different kings. Although his mission to turn these Syracusan tyrants into Platonic philosophers failed and as a result Plato later retired from politics, the ambition to unite philosophy and politics has been a recurring dream of political philosophy ever since. What may have appeared as laughable to Socrates and his companions might appear very different in other times and places. The idea of a philosophically educated statesman—the later model of the enlightened despot—has resonated throughout the modern era where philosophers—one thinks of names like Machiavelli, Hobbes, Rousseau—all sought the ear of political leaders or those who could help to convert their political ideas into practice.

Most of the objections to Plato’s philosopher-king have centered on the practicability of the idea. Beyond this, however, there is a problem with the very cogency of the concept. Can philosophy and politics actually be united? The needs of philosophy seem quite different from the needs of political rule. Can one imagine Socrates willingly giving up one of his conversations for the tedious business of legislation and administration? The philosopher as described by Plato is someone with knowledge of the eternal Forms lying behind (or beyond) the many particulars. But just how does this kind of knowledge help us deal with the constant change and flux of political life? Plato does not say. It is not enough that the philosopher have knowledge of the Forms; this knowledge must be supplemented by experience, judgment, and a sort of practical rationality. On top of this, there is the question of the potential abuse of political power by the philosopher. Philosophers are not thinking machines but human beings composed of reason, spiritedness, and appetite. Will not even philosophers offered the possibility of absolute political power be tempted to abuse their positions?

The question we have to ask ourselves, then, is to what problem is the philosopher-king intended as the answer. Plato seems to draw our attention to the fact that political power is the deepest aspiration of philosophy. The Republic as a whole is a surrogate for Socrates’s failed ambition to rule Athens and Plato’s failed attempt to serve as an adviser to a king in Sicily. There are at least two implications that follow from this reading. The first is the view that Plato is the true founder of the revolutionary tradition, one that seeks to unite theory and practice, reason and reality, that reaches its culmination in the doctrines of Hegel and Marx. Plato, on this reading, is the founder of the view that politics is an activity guided by intellectuals, theoreticians, or philosopher-priests. It is this view of politics that has been consistently deplored by the conservatives of the philosophical tradition from Aristotle to Montesquieu to Burke, who have all been deeply suspicious of the efforts to reform politics in accordance with a plan or program of reason.

But there is another reading of the Republic, however, that stresses the ultimate impossibility of uniting philosophy and the city and that stresses not only the dangers to the city but also the dangers to philosophy. The effort to turn philosophy into a tool of political rule necessarily turns philosophy itself into an “ideology,” a form of propaganda forced to resort to lies, distortions, and half-truths in order to ensure its hold on political power. One aspect of the Republic that frequently goes unmentioned is that there are no non-Platonists in the city. The effort to maintain absolute control over thought cannot help but become tyrannical. Philosophy requires a certain distance, a certain independence, from the city if it is to remain a critical activity and not simply a tool of political power. Seen from this point of view, the proposal for philosopher-kings must be adjudged a failure. It demonstrates, at least for some readers, that politics and philosophy must maintain a respectful distance from one another.

The Cave and the Sun

The relation of philosophy to political power is the explicit theme of one of Plato’s most enduring images: the cave (514a–17a). Here Socrates challenges Glaucon to “make an image of our nature in its education and want of education” (514a). The image is of a cave in which from childhood its inhabitants have been shackled to one another facing a wall and have seen only the images projected on the wall from a fire burning behind them. The image is something like a modern movie theatre or a television screen where the spectators absorb the images they see in front of them. As a result the “prisoners”—for that is what they are—are never allowed to see the objects themselves that are projected on the wall, only the shadows of these objects. These persons—passive and enthralled—Socrates claims are “like us” (515a). The objects reflected on the wall are described as “artifacts”—statues of wood and stone and the like—that are manipulated by “puppet handlers.” These puppeteers are in the first instance the legislators of the city, its founders, statesmen, and legislators, the bringers of law and codes of justice. Next to them are the poets of the city, its mythologists, historians, and artists; and next to them are its craftsmen, architects, city planners, and designers. All of these form the horizon within which the collective life of the city takes place.

But then imagine, we are asked, that one of these prisoners escaped, that someone dragged him away “by force” in such a way that he could no longer see the fire projecting the shadows but was led out of the cave into the sunlight, the life-giving force, by which the cave itself was, however dimly, illuminated. Socrates describes this situation as having one’s soul “turned around,” the Greek word for which is periagogē. This kind of soul-turning is tantamount to a form of conversion moving far beyond the kind of politically useful education described earlier in the Republic:

SOCRATES: “Education is not what the professions of certain men assert it to be. They presumably assert that they put into the soul knowledge that isn’t in it, as though they were putting sight into blind eyes.”

GLAUCON: “Yes,” he said, “they do indeed assert that.”

SOCRATES: “But the present argument, on the other hand,” I said, “indicates that this power is in the soul of each, and that the instrument with which each learns—just as an eye is not able to turn toward the light from the dark without the whole body—must be turned around from that which is coming into being together with the whole soul until it is able to endure looking at that which is and the brightest part of that which is.” (518 c–d)

This metaphor of the turning of the soul is the Platonic image of education. This is not a pleasant experience. It requires us to call into question all of the comfortable certainties that we had previously held to be true, good, and beautiful. It is common in the literature on Plato to think of this as some kind of religious conversion, and Plato often writes as if philosophy requires a retreat from society to the inner citadel of the soul. But this ascetic model of philosophy fails to account for the experience of the cave. Philosophy is fundamentally a social art and requires others to engage in it. It entails a rigorous training that begins with mathematics and culminates in the comprehensive study of “dialectic,” or the art of conversation. The education of the philosopher teaches not withdrawal from but participation in the world.

Socrates next asks the reader to imagine that the philosopher returns to the cave. How would he or she be greeted? Appear to the other cave dwellers? Readjust to the light or the lack of it? Such a person, Socrates admits, would cut a “graceless” figure in attempting to convey to the other troglodytes in the cave what had been seen on the outside. Such a person might become an object of innocent fun or of good-natured teasing, but more likely of envy, ridicule, or contempt. On Plato’s telling, he might even find himself persecuted, harassed, and threatened with death as a dangerous enemy of the people.

The story of the cave is surely one of Plato’s most pessimistic tales of the relation of philosophy to political power. The question that the story begs us to consider is, why would the philosopher, after escaping his shackles and seeing the sun, consent to return to the cave at all? Would not anyone prefer to remain aloof from politics—compared by Socrates to immigrating to a colony on the Isles of the Blessed—to the guarantee of failure and even death upon one’s return? Would not compelling the philosophers to return to the cave be a manifest injustice to them, making them give up the best life? It is this question that is posed by Glaucon in the following bit of dialogue:

SOCRATES: “Then our job as founders,” I said, “is to compel the best natures to go to the study which we were saying before is the greatest, to see the good and to go up that ascent; and, when they have gone up and seen sufficiently, not to permit them what is now permitted.”

GLAUCON: “What’s that?”

SOCRATES: “To remain there,” I said, “and not be willing to go down again among those prisoners or share their labors and honors, whether they be slighter or more serious.”

GLAUCON: “What?” he said. “Are we to do them an injustice and make them live a worse life when a better is possible for them?” (519 c–d)

Socrates’s image seems to have worked its magic. It seems to have disenthralled Glaucon, if only temporarily, of his desire for political rule. Its point is that the city, even Kallipolis, is nothing but a cave and its inhabitants prisoners in comparison to the beauties of philosophy. As the image suggests, each of us is an inhabitant of a cave of our own; it may be better or worse, depending on the nature of its legislators, its poets, and its artists, but it can never be anything other than a cave. The prisoners facing the wall are not symbolic of a particularly bad or unenlightened community; they are the citizens of any possible community. By this time even Glaucon—the warlike Glaucon!—is complaining that it would be unjust to force the philosopher to return to rule the city.

The story of the cave reveals, more clearly than anything, the limitations of the city-soul analogy proposed by Socrates in book 2. Although the individual and the community may be like each other in some respects, Plato wants to show that at the highest level, in the crucial respect, they are fundamentally at odds. The aspiration of the soul, its erotic desire to escape the conventional and restrictive bonds of the community, remains the deepest impulse of philosophy. Even the best city will be experienced as a prison by those who have embarked on the long, soul-turning journey of education. We may never be able to live entirely outside the community, but we also cannot remain content within it. In this respect the Republic is not just a work of philosophy. It is the greatest bildungsroman ever written.

Plato’s Democracy and Ours

How would Socrates respond to a regime such as ours and, most important, what have we to learn from this confrontation?

In one sense, the Republic is the most antidemocratic book ever written. Its defense of philosophic-kingship is a direct repudiation of Athenian democracy. Its conception of justice as “minding one’s own business” is a rejection of the Athenian belief that any citizen has sufficient all-round knowledge to participate in the offices of government. Yet it is important to recall that Athenian democracy is not American democracy. Plato thought of democracy as rule of the many, which he associated with the unrestricted freedom to do as one likes. This is a far cry from American democracy based on a constitutional system of checks and balances, the rule of law, and a government created for the protection of individual rights. The differences between Athens and Washington could not be more striking on the surface.

Even if the institutions of American democracy are not what Plato had in mind in his rejection of democratic politics, there is still a condition of modern democratic life that comes very close to what he described. It is not only the politics but the culture of democracy that is of concern. Consider the following passage from book 8 of the Republic: “He [the democratic man] also lives along day by day, gratifying the desire that occurs to him, at one time drinking and listening to the flute, at another downing water and reducing; now practicing gymnastics, and again idling and neglecting everything; and sometimes spending his time as though he were occupied with philosophy. Often he engages in politics and, jumping up, says and does whatever chances to come to him; and if he ever admires any soldiers, he turns in that direction: and if it’s moneymakers, in that one. And there is neither order nor necessity in his life, but calling this life sweet, free, and blessed he follows it throughout” (561c–d).

This account should be instantly recognizable when applied to the modern democratic individual, especially the references to dieting and exercise coupled with bouts of indulgence and moral neglect. What Plato (like Tocqueville centuries later) discerned in democracy was a certain type of materialism that elevated pleasure above all else and fostered an unwillingness to sacrifice for ideals. Democracy, as the passage above makes clear, fosters a sham universality by exciting all manner of strange interests and passions. It makes it exceedingly difficult to concentrate on the very few things that give life a sense of wholeness and importance.

What bothers Socrates most about democracy, however, is its tendency toward a form of moral anarchy that confuses liberty with license and authority with oppression. It is in this section of the Republic that Adeimantus asks: “Won’t we with Aeschylus say whatever comes to our lips?” (563c). The idea of having the liberty to say “whatever comes to our lips” sounds to Plato like a kind of blasphemy, the view that nothing is shameful and everything is permitted. There is here a license that comes from the denial of any restraints on our desires or a kind of hedonistic belief that because all desires are equal, all should be permitted.

Plato’s views on democracy are not all negative. After all, it was a democracy that produced Socrates and allowed him to philosophize freely until his seventieth year. This would never have been permitted in Sparta or any other city of the ancient world. Furthermore, Plato may have had reason to reconsider the democracy in Athens in the letter that he wrote near the end of this life, where he called the democracy a “golden age” in comparison to what went after it. Plato seems to agree with Winston Churchill that democracy is the worst regime—except for all the others that have been tried.

So what is the function of Kallipolis? What purpose does it serve? The philosopher-king may be an object of wish or hope, but Plato realizes that the occurrence of such a ruler is not to be expected. The philosophical city is introduced as a metaphor to help us understand the education of the soul. The reform of politics may not be within our power, but the exercise of self-control always is. The first responsibility of the individual who wishes to engage in political reform is to reform himself. This point is made near the very end of the Republic where Socrates speaks not of the soul “writ large” but of “the city within” (591d). The dialogue once again turns from the city to the soul:

SOCRATES: “Yes, by the dog,” I said, “he will [be engaged with] his own city [Kallipolis], very much so. However, perhaps he won’t in his fatherland unless some divine chance coincidentally comes to pass.”

GLAUCON: “I understand,” he said. “You mean he will in the city whose foundation we have now gone through, the one that has its place in speeches, since I don’t suppose it exists anywhere on earth.”

SOCRATES: “But in heaven,” I said, “perhaps, a pattern is laid up for the man who wants to see and found a city within himself on the basis of what he sees. It doesn’t make any difference whether it is or will be somewhere. For he would mind the things of this city alone, and of no other.” (592a–b; emphasis added)

This is a point that is often lost, that the Republic is above all a work on the reform of the soul. This is not to say that it teaches us withdrawal from political responsibilities. Not at all. Philosophy, certainly Socratic philosophy, requires friends, comrades, conversation; it is not something that can be usefully pursued in isolation. Socrates clearly understands that those who want to reform others must first reform themselves, must “found a city within himself,” but many who have tried to imitate him have been less careful.

It is very easy to confuse, as many have done, the Republic with a recipe for tyranny. The twentieth century is littered with the corpses of those who have set themselves up as philosopher-kings: Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Khomeini to name the most obvious. But such men are not philosophers; their pretensions to justice are just that, pretensions, expressions of their vanity and ambition. For Plato, philosophy was in the first instance a therapy for the passions, a way of setting limits to the desires. This is precisely the opposite of the tyrant, whom Plato describes as a person of limitless desires, lacking the most rudimentary kind of governance, namely, self-governance.

The difference between the philosopher and the tyrant illustrates two very different conceptions of philosophy. For some, philosophy represents a form of liberation from confusion, from unruly passions and prejudices, a therapy of the soul that brings peace and satisfaction. For others, philosophy is the source of the desire to dominate, it is the basis of all forms of tyranny and the great age of ideologies through which we have just passed. The question is, since both tendencies are at work within philosophy, how do we encourage one side but not the other? As that great philosopher Karl Marx once asked: “Who will educate the educator?” Exactly. Whom do we turn to for help?

There is no magic solution to this question, but the best answer I know of is Socrates. He showed people how to live and, just as important, how to die. He lived and died not like most people, but better, and even his most vehement critics admit that.