CHAPTER 5

Aristotle’s Science of Regime Politics

Alexander the Great, 356–323 B.C.E., as a youth listening to his tutor Aristotle. Ca. 1875. Photo credit: The Print Collector / Alamy

There is a story about the life of Aristotle the essentials of which run something like this: Aristotle was born; he spent his life philosophizing; and then he died. There is probably more to the life of Aristotle than these facts admit, but to some extent this captures the way in which he has been perceived: as the ultimate philosopher.1

Aristotle was born in 384 B.C.E. in Stagira in the northern part of Greece in what is now Macedonia. At the age of about seventeen—approximately the age of an undergraduate—he was sent by his father to study in Athens at the Academy established by Plato. But unlike most undergraduates, for the next twenty years Aristotle remained attached to the Academy, where he was later hired as a teacher. Is it not remarkable to consider that Plato and Aristotle, two people we think of as founders of the Western tradition, both lived and taught at the same place? We can only wonder what kinds of conversations they had over their many years together.

After the death of Plato, due perhaps to the choice of his successor at the Academy, Aristotle left Athens, first for Asia Minor and later for Macedonia, where he had been summoned by King Philip II to establish a school for the children of the Macedonian aristocracy. It was here that he first met and taught Philip’s son, Alexander, who later went on to conquer the entire Greek world. Aristotle later returned to Athens and established a school of his own, the Lyceum. There is a story according to which Aristotle was himself brought up on capital charges, as was Socrates, due to another wave of politically motivated hostility to philosophy. Rather than staying to drink the hemlock, Aristotle was reported to have left Athens saying he did not wish to see the Athenians sin against philosophy a second time. This story, even if apocryphal, is revealing.

Aristotle has often been described as the first political scientist: he is dry. Unlike his intellectual godfather, Socrates, who wrote nothing but conversed endlessly, and unlike his own teacher Plato, who wrote imitations of those endless Socratic conversations, Aristotle wrote disciplined and thematic treatises on virtually everything from biology to ethics, from metaphysics to literary criticism. Aristotle, one assumes, would have received tenure in any number of departments here at Yale, while Socrates could not have applied to become a teaching assistant. Like the image of him in Raphael’s famous painting The School of Athens, Aristotle kept his feet planted firmly on the ground: no flights of fantasy, no science fiction, no imaginary republics will enter his works.

These differences conceal others. While Plato’s dialogues weave endless and fascinating problems and paradoxes, Aristotle seems never to have been bothered by bouts of skepticism or doubt. He was the first to give form and shape to the discipline of political science. He set up its fundamental terms and concepts; he elaborated its basic questions and problems; he was the first to give conceptual clarity and rigor to the vocabulary of politics. There is virtually no issue we study today that was not first identified by Aristotle. His works like the Politics and the Nicomachean Ethics were intended as works of political education. They were designed less to recruit potential philosophers than to shape and educate citizens and future statesmen. His works were not “theoretical” in the sense of constructing abstract models of politics, but advice-giving in the sense of serving as an arbitrator over civic disputes. Unlike Socrates, who tended to denigrate political life as a cave, Aristotle took seriously the dignity of the city and showed the way that philosophy might be useful to citizens and statesmen alike.

It has sometimes been said that Aristotle’s political theory is related “directly” to political life. He did not set out to undermine the political order or to exercise a radical change of orientation upon the knower, as Plato seems to have done. His goal was to know more closely, to put in better order, what it is we already know. Accordingly, there is a greater respect for the opinions—the endoxa—that ordinary individuals already hold about the world in which they live. This feature of Aristotle’s thought has been nicely captured by an English reader: “Aristotle states clearly that moral theory must be in accord with established opinions and must explain these opinions as specifications of more general principles. An unphilosophic man of experience, who is of good character, usually reasons correctly on practical matters. Therefore Aristotle argues that acceptable moral theory will give a firm foundation to the principles that normally guide the decisions of the men whom we normally admire. Acceptable theory will not undermine established moral opinions nor bring about systematic moral conversion.”2 The claim expressed here that theory “must be in accord” with our ordinary perceptions and experience of the world is the key to Aristotle’s statecraft.

Yet there is still a profound enigma surrounding Aristotle’s political works. What were the politics of Aristotle’s Politics? Aristotle lived at the cusp of the world of the autonomous city-state. Within his own lifetime he would see Athens, Sparta, and the other cities of Greece swallowed up by the great Alexandrian empire to the north—the first great wave of what would later be called “globalization.” What we think of as the golden age of Greece was virtually at an end. Other Greek thinkers of his time, notably a rhetorician named Demosthenes, wrote a series of speeches, the Philippics, to warn his contemporaries about the danger posed to Athens from the Macedonians to the north. Yet Aristotle was completely silent on these truly epoch-making changes. What did he think of them?

Aristotle’s extreme reticence is perhaps the result of his foreignness to Athens. He was not an Athenian and therefore lacked the protections of a citizen. At the same time, this reluctance may have been a response to the fate of Socrates and the politically endangered situation of philosophy. Yet for a man as notoriously secretive and reluctant as Aristotle, his works acquired canonical status. He became an authority, really the authority, on virtually everything. Maimonides could refer to him in the twelfth century as “the master of those who know.” For Thomas Aquinas, writing in the thirteenth century, Aristotle was referred to simply as “the Philosopher.” Period. There was no philosophy but Aristotle’s. For centuries the authority of Aristotle went virtually unchallenged.

Naturally each of these thinkers read Aristotle through his own lens. Aquinas read him as a defender of monarchy, and Dante in his book De Monarchia saw Aristotle giving credence to the idea of a universal monarchy under the leadership of a Christian prince. Thomas Hobbes saw him completely differently. For Hobbes, Aristotle’s Politics taught a dangerous doctrine of republican government that he had seen practiced during the Cromwellian period in the England of his time and that had been used to justify regicide, the murder of a king. “From the reading, I say, of such books, men have undertaken to kill their kings because the Greek and Latin writers, in their books and discourses of policy, make it lawful and laudable for any man so to do, provided, before he do it, he call him tyrant,” Hobbes wrote in Leviathan (XIX, 14). Aristotle’s doctrine that man is a “political animal,” Hobbes believed, could only result in regicide. There are still echoes of Aristotle in the later writings of democratic political theorists from Tocqueville to Hannah Arendt.

This brings us back to the enigma of Aristotle. Who was this strange and elusive man, and what did he believe? The best place to start is with his views on the naturalness of the city.

Political Psychology

Perhaps the most famous doctrine found in the Politics is Aristotle’s statement that man is by nature a political animal. What does this mean?

Aristotle’s reasoning is stated succinctly on the third page of the Politics where he remarks that “every polis exists by nature” and goes on to infer that man is by nature the zōon politikon, the political animal. His reasoning is worth following here in some detail. “That man,” he says, “is much more a political animal than any kind of bee or herd animal is clear. For we assert, nature does nothing in vain; and man alone among the animals has speech.” While other species, he notes, may have voice that can distinguish pleasure from pain, logos is more than this. “But logos serves to reveal the advantageous and the harmful and hence also the just and the unjust. For it is peculiar to man as compared to the other animals that he alone has a perception of good and bad and just and unjust and other things” (1253a). So says Aristotle.

In what sense, though, is the city “by nature” and man a “political animal”? Aristotle appears to give two different accounts. In the opening pages he gives us something like a natural history of the polis. The polis is natural in the sense that it grows out of lesser forms of human association. First comes the family, then an association of families in a village, and then an association of villages that form a city. The city is natural in that it seems to be the most highly developed form of human association. But the city is natural in a second and more important sense. The city is said to be natural in that it allows human beings to achieve and perfect their telos or natural end. We are political animals because participation in the life of the polis is necessary for the achievement of human excellence. A man who is without a city, Aristotle says, must either be a beast or a god, that is, above humanity or below it (1253a). Our political nature is our essential characteristic.

When Aristotle claims, then, that man is by nature political, he is doing more than advancing a truism. He is advancing a philosophical postulate of great power and scope. In saying that man is by nature a political animal, he is not saying that there is some kind of biologically implanted desire that leads us to engage in political life. This would imply that we engage in politics as spontaneously and avidly as spiders spin webs or beavers build dams. Aristotle is not a kind of sociobiologist in the manner of E. O. Wilson.

Man is a political animal because we alone among the species are possessed of the power of speech. Speech or reason, far from limiting our behavior, gives us a latitude or freedom of choice not available to other species. It is reason, not instinct, that makes us political. But what is the connection between reason or the capacity for rationality and politics? It is reason that gives us the ability to judge, to deliberate, and to determine collective affairs such as war and peace, freedom and empire. Speech is what creates a community or, as Aristotle says, a sharing in what is just and unjust.

But to say that man is a political animal by nature is not just to say that we become fully human by participating in the life of our city. It means more. The form of association that leads to our perfection is necessarily something specific. The polis, as Aristotle conceived it, is a small society, what today might be called a “closed society.” His word for such a city was eusunoptos. This is often translated as “easily taken in at a glance” or “well taken in at one view”: “There is a certain measure of size in a city as well, just as in all other things—animals, plants, instruments: none of these things will have its own capacity if it is either overly small or excessive with respect to size.… Similarly with a city as well, the one that is made up of too few persons is not self-sufficient, though the city is a self-sufficient thing, while the one that is made up of too many persons is with respect to the necessary things self-sufficient like a nation, but is not a city: for it is not easy for a regime to be present. Who will be general of an overly excessive number or who will be herald, unless he has the voice of Stentor?” (1326a–b).

It is questionable if even during Aristotle’s lifetime the polis could be truly regarded as easily surveyable. Attica was approximately the size of Rhode Island, and that, even though small by American standards, can scarcely be “taken in at a glance.” Only a relatively closed society that is governed by face-to-face relations and can be held together by bonds of trust, of friendship, and of intimacy satisfies Aristotle’s criterion for a polis. Only a city small enough to be governed by relations of trust and friendship can be political in the true sense of the term. The alternative to the city—the empire—can only be ruled despotically.

It follows that the city by nature can never be a universal state and not even the modern nation-state. The universal state or all-comprehensive society will exist on a lower level of humanity than a closed society that over time has made a supreme effort at self-perfection. The city will always exist in a world with other cities or states based on different principles that may be hostile to its own, which is to say, not even the best city can exist without a foreign policy. Being a political animal means distinguishing fellow citizens and friends from enemies. A good citizen of a democracy will not be a good citizen in another type of regime. Partisanship and loyalty to one’s own way of life are required for a healthy city. Friend and enemy are thus natural and ineradicable political categories. Just as we cannot be friends with all persons, so the city cannot be friends with all other states. War and the virtues necessary for war are as natural to the city as are the virtues necessary for peace.

Note that Aristotle does not tell us—at least not yet—what kind of city or regime is best. How will such a city be governed? By the one, the few, the many, or some combination of the three? At this point we know only the most general features of the city. It must be small enough to be governed by a common language of justice or the common good. It is not enough merely to speak the same words; what shapes a city are common experiences and a common memory. The large polyglot multiethnic communities of today lack by Aristotle’s standards a sufficient basis for mutual trust and friendship so necessary for human well-being.

The citizen of such a city can only reach perfection through actively participating in the offices of the city. Again, a large cosmopolitan state may allow each individual the freedom to live as he or she likes, but this is not freedom as Aristotle understands it. Freedom only comes with the exercise of political responsibility, responsibility for and oversight of the well-being of one’s fellow citizens. It follows, then, that freedom does not mean simply living as we like; it must be informed by a sense of moral restraint, an awareness that not all things are permitted. The good society will be one that promotes a sense of moderation, restraint, and self-control inseparable from freedom. All of the above is suggested in Aristotle’s claim that man is a political animal.

Slavery and Inequality

Whatever we may think about Aristotle’s views on the naturalness of the polis, we must also confront his famous—or infamous—doctrine of the naturalness of slavery. The naturalness of slavery is said to follow from Aristotle’s belief that inequality is the rule between human beings. If this is true, Aristotle’s Politics would seem to stand condemned as one of the most antidemocratic works ever written. How, then, should we approach the book?

In the first place, we should avoid two equally unhelpful responses. The first is that we must not avert our eyes from those harsh, unappealing aspects of Aristotle’s thought and pretend he never said such things. We should avoid the temptation to airbrush or sanitize Aristotle in order to make him appear more politically acceptable. But we should also resist the opposite temptation to reject Aristotle out of hand because his views do not correspond with our own. The question is, what did Aristotle mean by slavery? Who did he think was the slave by nature? Until we understand what he meant about these most basic questions, we have no basis for either accepting or rejecting his teaching.

The first point worth noting is that Aristotle did not simply assume slavery was natural because it was practiced by the Greeks. You will notice that he frames his analysis in the form of a debate. There are some, he says, who believe that slavery is natural because ruling and being ruled is a pervasive distinction; but others believe that the distinction between master and slave is not natural but grows out of long-standing tradition and custom (1253b). In other words, is slavery by nature or by convention? Even in Aristotle’s time slavery was controversial and elicited different opinions.

Here is one of those moments where Aristotle seems almost maddeningly open-minded. He is willing to entertain arguments from both sides of the debate. He agrees with those who deny that slavery is justified by war or conquest. Wars, he remarks, are not always just, and so it cannot be assumed that those taken captive in war are justly enslaved. Similarly, he denies that slavery is appropriate only for non-Greeks. There are no racial or ethnic characteristics that distinguish the natural slave from the master. There is no hint of what we call “racism” in Aristotle’s views. And in a stunning admission he says that while nature may intend to distinguish the free man from the slave, “the opposite often results” (1254b). Now we are confused. Earlier, he said that nature does nothing in vain, but now he says that nature sometimes misses the mark. How is that possible? How can nature be mistaken? Such complications should alert the careful reader.

At the same time, Aristotle agrees with those who defend the thesis of natural slavery. Slavery is natural because we cannot rule ourselves without restraint of the passions. He shows himself a good student of Plato. Restraint or self-control is necessary for freedom and self-government. A person who is a slave to his passions is unable to exhibit the characteristics of a free human being. And what is true of restraint over one’s own passions and desires is true of restraint and control over others. Just as there is a hierarchy in the soul, with reason ruling the passions, so there is a social hierarchy, with rational persons ruling thoughtless ones. The natural hierarchy of master and slave is, then, a hierarchy of moral intelligence and the capacity for rational self-control.

But how did this come to be? Is the hierarchy of intelligence a genetic product or the result of nurture and education? If the latter, if differences of intelligence and moral character are a product of upbringing, can slavery ever be justified as natural? Is it not unjust that one person is elected to a position of privilege and education while another is fated to a life of anonymity and obscurity? Aristotle calls man the “rational animal,” suggesting that all human beings have a desire for knowledge, a desire to cultivate the mind and live as free persons. The famous opening line of his Metaphysics reads: “All men have a desire to know” (980a). The phrase “all men” clearly suggests something universal in this desire. If all men have a desire to know, then all men have an aspiration to rationality. The best regime would seem to be an aristocracy that had widened itself into a meritocracy of talent and intellect.

Aristotle still regards education—true, liberal education—as the preserve of the few. The kind of discipline and self-restraint necessary for an educated mind is unequally divided among human beings. It follows that the regime according to nature will be some kind of aristocracy of education and training, an aristocratic republic where an educated elite governs for the good of all. Aristotle’s republic is devoted to cultivating a high level of citizen virtue where this means those qualities of mind and heart necessary for self-government. These qualities, he believes, are necessarily the preserve of the few, of a small minority of citizens capable of sharing in the administration of justice and in the offices of the city. These few constitute Aristotle’s ruling class.

Aristotle’s conception of an educated aristocracy—something different from, but still related to, the Platonic notion of the philosopher-king—is not as far from our own experience as we might think. By education (paideia) Aristotle is speaking not of philosophy in any very precise sense but of a broader sense of intellectual culture (arts, literature, music). It is this sense of an aristocracy of education that Thomas Jefferson endorsed in a letter to John Adams. Jefferson distinguished between the “natural aristocracy” based on talent and intellect and the “artificial aristocracy” based on wealth and birth. “The natural aristocracy,” he wrote, “I consider as the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society.… May we not even say that that form of government is best which provides most effectually for a pure selection of the natural aristoi into the offices of government?” For Jefferson, it was representative institutions, in particular the institution of election, that was the best means of separating “the aristoi from the pseudo-aristoi, of the wheat from the chaff.”3

For those surprised to see Jefferson put in the same company with Aristotle, consider also the case of the nineteenth century’s greatest liberal mind, John Stuart Mill. In his Considerations on Representative Government, Mill was deeply concerned that the extension of the suffrage would result in the rise of mass democracy and the loss of influence for the educated minority. Accordingly, he embraced the scheme of voting proposed by Hare and Fawcett for its endorsement of proportional representation among different classes of voters in order to offset the disadvantages of “one man, one vote”:

The natural tendency of representative government, as of modern civilization, is toward collective mediocrity; and this tendency is increased by all reductions and extensions of the franchise, their effect being to place the principal power in the hands of classes more and more below the highest level of instruction in the community. But though the superior intellects and characters will be necessarily outnumbered, it makes a great difference whether or not they are heard.… In the old democracies there were no means of keeping out of sight any able man: the bema was open to him; he needed nobody’s consent to become a public adviser. It is not so in a representative government: and the best friend of representative democracy can hardly be without misgivings that the Themistocles or Demosthenes, whose counsels would have saved the nation, might be unable during his whole life ever to obtain a seat.4

Before we reject Aristotle’s account of the republic as insufferably elitist and antidemocratic, we must ask ourselves a difficult question. What else is Yale but an elite institution intended to educate—morally and intellectually—potential members of a leadership class? Can anyone get into Yale? Should the doors be open to everyone? Does it not require precisely those qualities of self-control, discipline, and deferred gratification necessary to achieve success here? Is it any coincidence that graduates from Yale and a small number of other elite colleges and universities find themselves in the highest positions of government, business, law, and the academy? Is it unfair or unreasonable to describe this class as a natural aristocracy, an aristocracy based not on wealth or tradition but on talent and merit? Before we reject Aristotle as an antidemocratic elitist, take a look at yourself. So are you—or else you wouldn’t be here.

Regime Politics

Aristotle’s comparative anatomy of regime types occupies the central books of the Politics, books 3 to 6. The regime or politeia is the central concept of his political science. The term is in fact the word used for the title of Plato’s Republic, the book dealing with the best regime or kallipolis. Aristotle uses it to capture something akin to the basic constitutional structure of a community. A regime refers to the formal institutional design of a community, but also to something closer to what we call the way of life or culture of a people, their distinctive customs, manners, and habits.

Aristotle’s constitutional theorizing begins by asking: What is the identity of a regime? What gives it an enduring existence over time? One can distinguish between the matter and the form of the regime. The matter of a regime concerns the citizen body, that is, the character of those who constitute a city. He rejects the idea that a regime is defined by a group of people who inhabit a common territory. “The identity of a polis is not constituted by its walls,” he remarks (1276a). In other words, physical proximity alone does not characterize a regime. Similarly, Aristotle rejects the view that a regime can be a defensive alliance to avoid invasion by others. In our terms NATO would not be a regime. Finally, he denies that a regime exists simply when a number of people establish commercial relations with one another for purposes of trade. NAFTA or the WTO does not a regime make. A regime is none of the above. “It is evident,” Aristotle writes, “that the city is not a partnership in a location or for the sake of not committing injustice against each other and of transacting business” (1280b). So what is it?

We can say, then, that a regime is constituted by its citizen body. Citizens are those who share a common way of life and who may therefore participate in political rule. “The citizen in an unqualified sense,” Aristotle says, “is defined by no other thing so much as sharing in decision and office” (1275a), or as he puts it later, “Whoever is entitled to participate in an office involving deliberating or decision is a citizen of the city” (1275b). A citizen is one who not only enjoys the protection of the laws but also takes a part in shaping the laws, who participates in political rule and deliberation. Aristotle even notes that his definition of the citizen is most appropriate to citizens of a democracy where in his famous formulation everyone knows how “to rule and be ruled in turn” (1277a). It is his reflection on the character of the citizen that leads Aristotle to wonder whether the good citizen is the same as the good human being. Is the best citizen necessarily the best type of person?

Aristotle’s answer to this question is perhaps deliberately obscure. The good citizen, he remarks, is relative to the regime. The good citizen of a democracy will not be the same as a good citizen of a monarchy. Citizen virtue is regime relative. Only in the best regime will the good citizen and the good human being be the same. But this formula seems question begging. For what is the best regime? Is there a regime where the good human being and the good citizen are identical? Aristotle does not say—at least not yet. The point is that there are several kinds of regime and therefore several kinds of citizenship appropriate to each. Each regime is constituted not only by its matter but also by its form, that is, by a set of institutions and formal structures that give shape to its citizen body. Regimes or constitutions contain forms or formalities that determine how powers are shared or distributed within a community.

The citizens who constitute a regime, we have just seen, do more than occupy a common space or associate for the sake of mutual protection or convenience; they are held together by ties of common affection, loyalty, trust, and friendship. What does Aristotle mean by this? “This sort of thing [the political partnership],” he writes, “is the work of affection for affection is the intentional choice of living together” (1280a). Philia or friendship, he notes, is “the greatest of good things for cities,” for when people feel affection for each other they are less likely to fall into conflict (1262b). What Aristotle calls by the Greek word philia has strong overtones of comradeship between people who share a common fate or destiny. Political friendships may well entail intense rivalry and competition for positions of political office and honor. Civic philia is not without a strong element of sibling rivalry in which each citizen strives to outdo the others for the sake of the civic good. Siblings—as everyone knows—may be the best of friends, but this does not exclude strong elements of competition and even conflict for the attention of the parents. Fellow citizens are like siblings, all competing with one another for the esteem, affection, and recognition of the city that serves as a kind of surrogate parent.

When Aristotle says that citizens are held together by ties of common affection, he means something quite specific. The civic bond is something more than an aggregate of mere self-interest, as it will later be claimed by Hobbes and many contemporary political scientists. One cannot account for politics simply in terms of the rational calculation of interest alone. But when Aristotle speaks of affection he does not mean the bonds of personal intimacy characteristic of private friendships. Citizens need not be intimates, but they must think of themselves as part of a common enterprise. They are part of an enterprise association, by which I mean a joint endeavor. Where this is lacking, where there is a breakdown of civic trust, people cannot be citizens in the true sense of the word. What Aristotle means when speaking of civic affection is more like the bonds of loyalty and camaraderie that hold together members of a team or a club. These are more than ties of mutual convenience; they require a kind of loyalty—what social scientists call “social capital”—and mutual recognition. It is the kind of spiritedness people feel when they say, “There is no ‘I’ in ‘team.’ ” They are part of a collective that is greater than the sum of its parts. “The political partnership,” Aristotle writes, “must therefore be regarded as being for the sake of noble actions not [just] for the sake of living together” (1281a).

If the matter of a regime concerns the composition of its citizen body, its form concerns the distribution of powers. Aristotle defines the strictly formal aspect of the politeia twice in the Politics. The first time appears in book 3, chapter 6: “The regime is an arrangement of a city with respect to its offices, particularly the one that has authority over all matters. For what has authority in the city is everywhere the governing body and the governing body is the regime” (1278b).

The second definition of appears in book 4, chapter 1: “For a regime is an arrangement in cities connected with offices, establishing the manner in which they have been distributed, what the authoritative element of the regime is, and what the end of the partnership is in each case” (1289a).

From these two definitions we learn a number of things. First, Aristotle distinguishes regimes on the basis of their ruling body or ruling class. A regime concerns the manner in which power is divided in any community. This is what Aristotle means when he says that a regime is “an arrangement of a city with respect to its offices.” In other words, every regime will be based on some kind of judgment of how power should be distributed, to one person, the few, or the many. In every regime one of these groups will be dominant, will be the “ruling body” or ruling class in Aristotle’s term, and this will define the nature of the regime in question. Aristotle’s regime analysis is thus concerned with perhaps the oldest political question: “Who governs?”

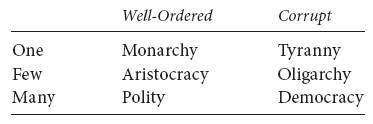

All regimes are dominated by the one, the few, or the many. But typical of Aristotle, after distinguishing regimes into three basic forms he goes on to complicate his initial formulation. He also distinguishes between regimes that are well ordered and those that are corrupt. His regime analysis is not only empirical; it is normative. On the well-ordered side he includes monarchy, aristocracy, and polity; on the corrupt side he includes tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy. Rule of one can be either monarchic or tyrannical; rule of a few either aristocratic or oligarchic; and rule of the many either constitutional or democratic. His table or catalogue of regime types looks something like the following:

What criteria does Aristotle use to distinguish well-governed from corrupt regimes?

There are two features that Aristotle believed necessary for a decent constitutional order. The first is the rule of law. No polity worthy of the name should be made to suffer self-interested rule of the few over the many or of the many over the few. The rule of law, as we shall see later, may not guarantee justice, but of one thing Aristotle was sure, namely, that justice, and hence political legitimacy, was not possible outside the framework of law. Regulation by law and responsibility to its citizens were deemed by him the necessary minimal conditions for what he termed polity or constitutional government. The second feature of a well-ordered regime is stability. Aristotle is generally reluctant to condemn any regime out of hand—even the badly ordered ones—so long as they maintain some modicum of order. In fact he provides reasoned arguments for the strengths and weaknesses of various regime types and can even be found offering advice to tyrants on how to make their regimes more stable. He considers no regime so entirely devoid of goodness that its preservation is not worth some effort.

For example, we find Aristotle defending democracy on the grounds that the many may collectively contain greater wisdom than the few. This argument is frequently referred to as the “wisdom of the multitude.” In book 3, chapter 11, Aristotle writes: “For because they are many, each can have a part of virtue and prudence and on their joining together, the multitude, with its many feet and hands and having many senses, becomes like a single human being, and so also with respect to character and mind” (1281b). We even hear Aristotle praising the democratic practice of ostracism, that is, exiling those individuals deemed to be preeminent in virtue or some other quality.

He makes a similar point in book 3, chapter 15, in describing the process of democratic deliberation, comparing it to a potluck dinner: “Any one of them taken singly is perhaps inferior in comparison to the best man; but the city is made up of many persons, just as a feast to which many contribute is finer than a single and simple one and on this account a crowd also judges many matters better than any single person. Furthermore, what is many is more incorruptible: like a greater amount of water, the many is more incorruptible than the few” (1286a). Here it is not so much the number as the diversity of offerings that add up to a feast.

Aristotle also can be found providing a defense of kingship and the rule of the one. In book 3, chapter 16, he considers the case of “the king who acts in all things according to his own will” (1287a). The kind of king he has in mind seems close to the Platonic idea of the philosopher-king. Aristotle calls it by the Greek word pambasileia, or literally a kind of universal kingship. He does not rule out the possibility of a person of “excessive excellence” who stands so far above the rest as to be their natural ruler.

How does one reconcile Aristotle’s account of the pambasileia with his earlier emphasis on the wisdom of the multitude? Does his suggestion of universal kingship reveal a hidden “Alexandrian” strain in his political thinking that owes more to his native Macedonia than to his adopted Athens? Later in the Politics Aristotle develops the thesis that under favorable conditions the Greeks could establish a universal hegemony over all the nations. Consider a famous passage from book 7, chapter 7: “The nations in cold locations, particularly in Europe, are filled with spiritedness [thymos] but relatively lacking in discursive thought and art; hence they remain freer, but lack political governance. Those in Asia, on the other hand, have souls endowed with discursive thought and art, but are lacking in spiritedness; hence they remain ruled and enslaved. But the stock of the Greeks shares in both—just as it holds the middle in terms of location. For it is both spirited and endowed with discursive thought, and hence both remains free and governs itself in the best manner and at the same time is capable of ruling all should it obtain a single regime” (1327b).

This passage is of enormous importance. Just as Aristotle believes one man might exercise rule over all Greeks, so too does he consider that under the right circumstances the Greeks could exercise a universal empire over all people. He does not rule out this possibility. Aristotle is a constitutional pluralist. He regards different regimes as being suitable for different situations. There is no one-size-fits-all model of political life, but good regimes may come in a variety of forms. The task of the political scientist is not to be a cheerleader for any one regime, it is to recognize that there are many different legitimate regimes that can satisfy different circumstances.

Nonetheless, Aristotle understands that a person of such superlative virtue is not to be expected. Politics is much more a matter of dealing with less-than-best conditions. Most regimes, for all practical purposes, will be a mix of oligarchy and democracy, by which Aristotle means a mix of the rich and the poor. It was not Marx but Aristotle who discovered the fact of class struggle. But unlike Marx’s, Aristotelian class struggle is not just a competition for resources or for control of the means of production but a struggle over positions of honor and status, ultimately over positions of political rule. It is, in short, political conflict, not economic incentives, that determines the regime.

It is a common misreading to think of Aristotle as stressing harmony and consensus over conflict and factional strife. This is clearly false. Every regime is a site of contestation where competing claims to justice and rule will be fought out. There is partisanship not only between regimes but within regimes where citizens are activated by often competing and incompatible understandings of justice. The members of the democratic faction, the poor, believe that because all men are equal, they should be equal in all things; the members of the oligarchic faction, the rich, believe that because men are unequal, they should be unequal in all things. Such rivalry is endemic to all politics; the attempt to remove the causes of conflict and create a community of interests would be an attempt to abolish politics. Politics is the art of the skillful management of conflict. How, then, to mediate the causes of faction before they lead to revolution and civil war?

Constitutional Government and the Rule of Law

Aristotle does propose various remedies to offset the competitive and potentially warlike struggle between the various factions. The most important of these is, again, the rule of law. Laws ensure the equal treatment of all citizens and prevent arbitrary rule at the hands of either the one, the few, or the many. Rule of law establishes a sort of impartiality, “for law,” Aristotle writes, “is impartiality”: “One who asks law to rule is held to be asking god and intellect alone to rule, while one who asks man, asks the beast. Desire is a thing of this sort; and spiritedness perverts rulers and the best men. Hence law is intellect without appetite” (1287a). But law is not the end of the story. It is only the beginning. Aristotle raises the question of whether the rule of law is to be preferred to the rule of men, even of the best individual. Typically, he examines the question from different points of view.

He begins by appearing to defend Plato’s view about the rule of the best individual: “The best regime,” he writes, “is not one based on written laws” (1286a). Law is a clumsy instrument of rule because laws deal only with general matters and cannot apply to particular situations. Further, the rule of law ties the hands of statesmen and legislators, who must always be prepared to respond to new and unforeseen situations.

At the same time, Aristotle makes the case for law. The judgment of an individual, no matter how wise, is subject to bias, whether due to passion, interest, or simply the fallibility of human reason. The sovereignty of the law, which is an imitation of wisdom, replaces the sovereignty of the human ruler. Further, he notes, no one person can oversee all things. This is a matter of practicability. But Aristotle also makes the case for law by claiming that no one can be trusted to be a judge in his own case. Doctors bring in other doctors when they are sick, just as trainers consult other trainers for fitness. Only a third party, in this case the law, is capable of adequately judging. The law can serve as a surrogate for the sovereignty of a single ruler.

So, should law be changed, and if so, how? Here again Aristotle presents different points of view. In book 2, chapter 8, he compares law to other arts and sciences and suggests that just as sciences such as medicine have exhibited progress and change, this is true for law, too. The antiquity of a law is no justification for its continued usage. Aristotle is not a Burkean conservative who identifies the ancestral with the good. He says as much: “In general all seek not the traditional but the good” (1269a).

Yet he recognizes that changes in law, even when the result is improvement, are dangerous: “It is a bad thing to habituate people to the reckless dissolution of laws,” he writes, “for the city will not be benefited as much from changing [laws] as it will be harmed through being habituated to disobey the rulers” (1269a). Sudden or frequent changes in the law, even where such changes aim at improvement, will result in unintended consequences. Lawfulness, like all the virtues, is a habit of behavior, and the habit of disobeying even an unjust law tends to make people altogether lawless. “For law,” Aristotle says, “has no strength with respect to obedience apart from habit … the easy alteration of existing laws in favor of new and different ones weakens the power of law itself” (1269a).

The most important remedy to the problem of faction is found in Aristotle’s theory of polity discussed in book 4. Polity actually goes by the same generic word, politeia, used for regimes in general that might be loosely translated by our term “constitution” or “constitutional government.” The essential feature of a polity or constitutional government is that it represents a mixture of the principles of oligarchy and democracy and therefore avoids the dominance of either extreme. By combining elements of the few and the many, polity is characterized by the dominance of the middle class. On this view, a polity with a middle class is more stable and more law abiding than regimes governed by the purely self-interested rule of the few or the many. The middle class is able to achieve the confidence of both extreme parties, and where it is sufficiently numerous, class conflict can be avoided: “Where the middling element is numerous factional conflicts and splits over the nature of the regimes occur least of all. And large cities are freer of factional conflict for the same reason—that the middling element is numerous” (1269a).

This passage should sound very familiar to readers of the Federalist Papers, who will recall James Madison’s proposal not to try to abolish or outlaw factions but to let them check and control one another in a large extended republic. The advantage of constitutional government is that each faction is able to speak of the regime as either a democracy or an oligarchy. Constitutional government is democratic because there is a common system of education and “a wealthy person is in no way marked off from a poor one.” It is oligarchic because political offices are determined by election and not by lot.5 There is, in short, something for everyone, and “none of the parts of the city would wish to have another regime” (1294b). Aristotle’s proposals for a mixture of both oligarchy and democracy also remind us of Madison’s call for a government where powers are separated, where “ambition must be made to counteract ambition” in the language of Federalist No. 51—in order to avoid the extremes of both tyranny and civil war. Aristotle seems to have discovered something like the American constitution centuries before the fact!

Political Science and Political Judgment

What is Aristotle’s political science? To ask this question is already to stake a claim. Does Aristotle have a political science—a science of politics—and if so, what is this science about? To begin to answer this question—even to begin just to think about it—requires that we stand back from Aristotle’s text and ask some fundamental questions about it: What does Aristotle mean by the political, what is the goal or purpose of the study of politics, and what is distinctive about Aristotle’s approach to the study of political things?

The core of Aristotle’s political science is based on the discovery of a certain kind of knowledge that he describes as practical reason (phronēsis). He distinguishes practical knowledge from two other forms: scientific or theoretical reason (epistēmē) and technical or productive knowledge (technē). Theoretical wisdom seeks out necessary or universal truths, what is true always and everywhere, such as those discovered in mathematics or logic. Technical know-how is the kind of instrumental knowledge involved in the production of useful objects. Practical knowledge, by contrast, is the knowledge of right action, where the end or aim of the action is the action itself performed well. It entails not a form of instrumental reasoning—knowing the most efficient means to produce a desired end—but is a kind of connoisseurship that involves knowing the right thing to do under the specific circumstances.

Aristotle is mainly concerned to distinguish the study of moral and political knowledge from purely theoretical pursuits such as mathematics or physics. In contrast to the theoretical sciences, the subject matter of politics admits of too much variation to yield law-like generalizations. Practical knowledge will always be provisional; it will produce truths that will hold for the most part but will always admit exceptions. What distinguishes practical judgment from both theoretical and productive knowledge is a sense of the fitting or the appropriate, an attention to the nuances or details of a particular situation. The phronimos—the person of practical reason—is the one able to grasp the fitting or the appropriate thing to do out of the complex arrangements that make up a situation. Above all, such a person embodies that special quality of insight and discrimination that distinguishes him or her from people of a more purely theoretical or speculative cast of mind.

Practical reason is, then, the type of knowledge appropriate to people situated in popular assemblies, courts of law, or any other place where deliberation takes place. It is neither theoretical knowledge aimed at abstract truths nor productive knowledge used in the manufacture of useful artifacts. This kind of practical wisdom entails insight and deliberation. We only deliberate over things where there is some choice. We deliberate with an eye to preservation or change. This kind of knowledge will be the art or craft of the skilled statesman concerned with what to do in a specific situation. It is less a body of true or universalizable propositions than a shrewd sense of know-how or political savvy. It is the skill possessed by the greatest statesmen—the fathers of the constitution, as it were—who create the permanent framework that allows lesser and later figures to manage change.

This Aristotelian quality of practical wisdom has been nicely developed, although without any explicit reference to Aristotle, in an essay by the English political philosopher Isaiah Berlin. In his essay entitled “Political Judgment,” Berlin asks what intellectual quality successful statesmen possess and how this quality differs from other forms of knowledge and rationality: “The quality that I am attempting to describe,” Berlin writes, “is that special understanding of public life (or for that matter private life) which successful statesmen have, whether they are wicked or virtuous—that which Bismarck had or Talleyrand or Franklin Roosevelt, or, for that matter, men such as Cavour or Disraeli, Gladstone, or Ataturk, in common with the great psychological novelists, something which is conspicuously lacking in men of more purely theoretical genius such as Newton or Einstein or Russell or even Freud.”6 “What are we to call this capacity?” Berlin continues: “Practical reason, perhaps a sense of what will work and what will not. It is a capacity for synthesis rather than analysis, for knowledge in the sense in which trainers know their animals, or parents their children, or conductors their orchestras, as opposed to that in which chemists know the contents of their test tubes, or mathematicians know the rules that their symbols obey. Those who lack this [quality of practical wisdom], whatever other qualities they may possess, no matter how clever, learned, imaginative, kind, noble, attractive, gifted in other ways they may be, are correctly regarded as politically inept.”7

What is necessary for political judgment is what Berlin calls a “sense of reality.” This does not mean simply knowledge of what will work and what will not, but a sense of what is possible and what is not. Judgment is not just a matter of fitting means to ends, but of knowing what is the fitting or appropriate thing to do under given circumstances. Good judgment in politics, just like the ability to judge good character in individuals, is not necessarily a matter of having more information or access to a larger body of facts, but the ability to see something before others do, knowing whom to trust and whom not to, and a willingness to accept responsibility for one’s mistakes.

But who, we want to know, is the person of practical judgment? Who is this paragon of the noble who serves as the standard of right action? Is the capacity for moral judgment a product of habituation or is it more like a gift of nature or grace, like the talent to paint or the ability to learn foreign languages? Are certain people just born with these abilities, or can they be acquired through practice and habit? The fact is that our natural talents and abilities are distributed very unequally and have little to do with our merit or desert; they are to a large degree the product of luck. Why does one person have a talent for the piano while another is tone deaf? Why does one person have the knack for moneymaking while another follows one dead end after another? Nature provides the raw materials; habit and practice help to give those materials form or shape, but judgment is ultimately the acquisition of a kind of connoisseurship that allows one to distinguish the appropriate from the inappropriate, the genuine from the ersatz. Aristotle’s motto could almost be: “Distinguish, always distinguish.”

What most distinguishes Aristotle’s concept of practical judgment is that it is emphatically addressed not to other political scientists and philosophers but to citizens and statesmen. His language stays entirely within the orbit of ordinary speech. Such language does not claim to be scientifically purged of all ambiguity but rather adopts standards of proof appropriate to debate in assemblies, courts of law, and council rooms. While contemporary political science is mainly concerned with advancing the claims of science (a body of true propositions), Aristotle is more concerned with finding ways of bringing peace to conflict-ridden situations. His political science is eminently practical or, as we might say, “normative.” It is the skill possessed by the most able political actors, a Themistocles or a Pericles to say nothing of a Lincoln or a Churchill. Aristotle’s approach does not claim to stand above or apart from the political realm as if he were viewing human affairs from a distant planet or like an entomologist observing the behavior of ants. Aristotle’s political science is civic-minded or patriotic. It seeks reasons for why political orders, even the less-than-best political orders in which we all live, are worth preserving and amending. From a present-day perspective, then, Aristotle’s approach seems radically “unscientific” because it culminates not just in knowledge but in action, action whose goal is the maintenance and preservation of the political regime.

Of course, present-day political scientists are not entirely neutral. They frequently insert their own “values” into their discussion. But these values are regarded by them as purely “subjective,” not a part of the science for which they speak. But this admits a problem. For if all values are subjective, that is, if no one has the right or authority to impose his or her values on another, then it follows that the only legitimate political order will be one that is “neutral” to the ways of life of its citizens, that maintains a strict wall of separation between the private sphere of values and the public sphere of law. But the political order that maintains or insists on the distinction between the public and the private, between law and morality, is a specific kind of political order. We call it a liberal regime. The question is whether any regime, even a liberal regime, can remain entirely neutral about the ways of life of its citizens. Isn’t asking us to remain value neutral like asking someone to view some physical object but from no particular point of view? It is an impossibility. In the end one might well wonder which approach is more scientific: Aristotle’s, which is explicitly and necessarily evaluative, which offers advice and exhortation about how to care for the political order, or contemporary political science, which claims to be neutral and nonpartisan, but which smuggles its values and preferences in through the back door.