CHAPTER 7

Machiavelli and the Art of Political Founding

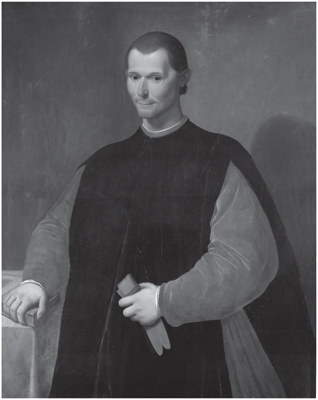

Portrait of Niccolò Machiavelli, 1469–1527. Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Photo credit: Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Machiavelli was a Florentine. To know that is to know virtually everything you need to know about him. I exaggerate, of course, but the point is that Florence was a city-state—a republic—and Machiavelli spent his life in the service of the republic. Living in Florence, the center of the Renaissance at the height of the Renaissance, he hoped to do for politics what his contemporaries Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo had done for art and sculpture. He hoped to revive the spirit of the ancients, of antiquity, but to modify and correct it by the light of his own experience. As he puts it in the Dedication of The Prince, his book is the product of “long experience with modern things and a continuous reading of ancient ones” (Dedication/3).1

To be sure, Machiavelli was not an ordinary Florentine. He was born in 1469 and grew up under the rule of the Medici, the first family of Florence, but lived to see them deposed by a Dominican friar by the name of Savonarola. Savonarola sought to impose on Florence a kind of theocracy, a republic of Christian virtue, but the Florentines being what they were, his experiment proved short-lived. In its place, a republic was established under a man named Piero Soderini (whose name appears several times in The Prince), where Machiavelli occupied the office of the secretary of the Second Chancery—a diplomatic post—for fourteen years from 1498 to 1512. After the fall of the republic and the return of the Medici, Machiavelli was tortured and then exiled from Florence to a small estate that he owned on the outskirts of the city. It was here during this life of political exile that he penned his major political works, The Prince, the Discourses on Livy, and the Art of War.2

It was also here that he wrote voluminous letters to friends, seeking knowledge of political events and happenings. In one letter to his friend Francesco Vettori he describes how he came to write his most famous book. “When evening comes,” he writes, “I return to my house and enter my study”:

On the threshold I take off my workday clothes, covered with mud and dirt, and put on the garments of court and palace. Fitted out appropriately, I step inside the venerable courts of the ancients, where, solicitously received by them, I nourish myself on that food that alone is mine and for which I was born; where I am unashamed to converse with them and to question them about the motives for their actions, and they, out of their human kindness, answer me. And for four hours at a time I feel no boredom, I forget all my troubles, I do not dread poverty, and I am not terrified by death. I have jotted down what I have profited from in their conversation and composed a short study, De principatibus, in which I delve as deeply as I can into the ideas concerning this topic, discussing the definition of a princedom, the categories of princedoms, how they are acquired, how they are retained, and why they are lost.3

The Prince is a deceptive book. What else would we expect? It is a work that everyone has heard of and perhaps has some preconception about. It is a book that has spawned scores of imitators. There are serious books, like Carnes Lord’s The Modern Prince, dealing with leadership issues in times of war, and James Burnham’s classic study The Machiavellians, defending the role of elite rule in modern society. But there are also books with titles like The Machiavellian Guide to Womanizing (by an appropriately named Nick Casanova), The Mafia Manager: A Guide to the Corporate Machiavelli, and my personal favorite, The Suit: A Machiavellian Approach to Men’s Style. We all know—or think we know—what the work is about. Machiavelli’s name is synonymous with deception, treachery, cunning, and deceit. Just look at his likeness. His smile—really a smirk—seems to say, “I know something you don’t know.” The difficulty with reading Machiavelli is that we already think we know all there is to know and consequently do not read him with the care he deserves. But there is more—much more—to Machiavelli than this.

Machiavelli was, above all, a revolutionary. In the Preface to his Discourses on Livy he compares himself with Christopher Columbus for his discovery of “new modes and orders.” What Columbus did for geography, Machiavelli will do for politics: discover a new continent, a new world, so to speak. Machiavelli’s new world, his new modes and orders, will require the displacement of the previous one. He makes this clear in the opening to chapter 15 of The Prince: “I depart from the orders of others,” he writes. “But since it is my intent to write something useful to whoever understands it, it has appeared to me more fitting to go directly to the effectual truth of the thing than to the imagination of it. And many have imagined republics and principalities that have never been seen or known to exist in truth; for it is so far from how one lives to how one should live that he who lets go of what is done for what should be done learns his ruin rather than his preservation” (XV/61). But what was Machiavelli’s revolution about?

This passage is often taken as providing the essence of Machiavellian realism, often called realpolitik, his appeal from the ideal to the real, from the Ought to the Is.4 Machiavelli’s call is to take one’s bearings from the “effectual truth of things”: do not look at what people say, look at what they do. To be sure, Machiavelli focuses on key features of reality: murders, conspiracies, coups d’état. He is more interested in the actual evils that men do than in the goods to which they aspire. You might even say that Machiavelli takes delight in demonstrating, much to our chagrin, the space between our lofty intentions and the actual consequences of our deeds.

And yet there is more—far more—to Machiavelli than the term “realism” connotes. The term may be deeply misleading. Machiavelli speaks the language of political innovation, renewal, and even redemption. The book draws on the biblical language of prophecy, and Machiavelli presents himself as a prophet of liberation. In the passage cited above, he boldly announces his break with—indeed, his repudiation of—all those who have come before him. He both replaces and combines elements from both Christianity and the Roman republic to create a new form of political organization distinctly his own: the modern state. He is the architect of the modern sovereign state that is given theoretical expression in the later writings of Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, to say nothing of contemporary writers on both the left and the right, from Max Weber and Carl Schmitt to Antonio Gramsci, the author of a book called The Modern Prince.

The Form and Dedication of The Prince

Machiavelli was a partisan of the new. But like all pathbreakers, he often combined his novelties with conventional pieties and forms. His writings are a curious combination of boldness and caution. His often conventional exterior almost always belies an unconventional interior. Consider just the form and dedication of The Prince.

The Prince appears on its surface to be the most conventional of books. It presents itself as a work in the long tradition of what is known as “mirror of princes,” that is, handbooks that attempt to advise a prince about how to behave, a kind of dos and don’ts of princely rule. Fair enough. The oldest work of this genre is Xenophon’s Education of Cyrus (Cyropaideia), which Machiavelli both misidentifies and includes on his required reading list (XIV/60). The appearance of conventionality is further supported by the opening words of the book: “It is customary.” Machiavelli wraps himself in the mantle of tradition. It is a work intended to ingratiate him to Lorenzo de Medici, the man whose name appears on the dedication page.

But look again. Consider the structure of the first three chapters. “All states, all dominions that have held and do hold empire over men, are either republics or principalities,” Machiavelli declares in the opening sentence of chapter one (I/5). He then asserts that in this work he will deal only with principalities, leaving the discussion of republics for elsewhere, one assumes his Discourses. Having distinguished principalities and republics as the only two kinds of regime worth mentioning, he goes on to distinguish between two kinds of principality: hereditary princes like Lorenzo, who have acquired their authority through tradition and blood line, and new princes.

But then Machiavelli goes on to tell the reader that the exclusive subject of the book will be the new prince—not Lorenzo at all, but precisely the kind of prince who has achieved his authority through his own guile, force, and cunning. The true addressee of the book must necessarily be the potential prince, someone with sufficient political audacity to create his own authority. The Prince is addressed to a new kind of leader, one who is prepared to create his own authority ex nihilo. But there is literally only one creator who is able to create from scratch. Machiavelli’s prince seems to be an answer to the creator described in the opening chapters of Genesis. The Prince describes a new kind of political leader emancipated from traditional forms of authority and virtue and endowed with a species of ambition, love of glory, and elements of prophetic authority that we today might call “charisma.”

Armed and Unarmed Prophets

So what, then, is the character of this new prince, and how does he differ from more conventional models of princely authority? In one of the most famous chapters of the book, entitled “Of New Principalities That Are Acquired Through One’s Own Arms and Virtue,” Machiavelli discusses the character of the new prince (VI/21–25). He begins by stating, perhaps overstating, the difficulties in establishing one’s authority. “A prudent man should always enter upon the paths beaten by great men, and imitate those who have been most excellent, so that if his own virtue does not reach that far, it is at least in the odor of it” (VI/22). One should do what archers do when attempting to reach a distant target, namely, aim one’s bow high, knowing that gravity will force the arrow down. In other words, set your sights high, knowing that you will probably fall short. So who are “the greatest examples” of princely rule that the prudent man should imitate?

Here Machiavelli gives a list of heroic founders of peoples and states: Moses, Cyrus, Romulus, Theseus, and so on. “As one examines their actions and lives,” he writes, “one does not see that they had anything else from fortune than the opportunity which gave them the matter enabling them to introduce any form they pleased” (VI/23). In short, these were founders who, like the biblical God, created ex nihilo, with only the occasion to act and the necessary virtues—strength of mind—to take advantage of their situation. “Such opportunities,” he continues, “made these men successful and their excellent virtue enabled the opportunity to be recognized; hence their fatherlands were ennobled by it and they became prosperous” (VI/23).

It is here that Machiavelli introduces his famous distinction between armed and unarmed prophets. “All the armed prophets conquered and the unarmed ones were ruined,” he concludes (VI/24). This seems to be—and is—a statement of sheer power politics. Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun, as a twentieth-century Machiavellian has said. But there is more than this. Why does Machiavelli compare the new prince to a prophet? What is a prophet? The most obvious answer is a man to whom God speaks. The biblical prophet—Nathan is a perfect example—is someone brought to chastise or rebuke rulers for their injustice and misuse of power. Machiavelli’s prophets, however, come armed. They come to assume power. There is only one figure on Machiavelli’s list who could qualify as a prophet in the strict sense, namely, Moses, whom he calls a “mere agent” who should be admired not for his skill “but for that grace which made him deserving of speaking with God” (VI/22).

But the prophet in Machiavelli’s sense is also someone who inhabits the imagination (fantasia) of a people. It is not enough that a prophet be obeyed; he must be believed. An interesting case in point is the treatment of Savonarola, a near-prophet, who failed, so to speak, only when words failed him. “He was ruined in his new orders as soon as the multitude began not to believe in them and he had no mode for holding firm those who had believed nor for making unbelievers believe” (VI/24). The lesson of Savonarola cannot be repeated too often. Savonarola did not fail because he was the prototypical unarmed prophet; the source of his failure was not just a failure of arms but of words: the people had ceased to believe in him. Machiavelli’s prophets may not be religious figures or the recipients of divine knowledge, but they must be persons of exceptional personal qualities that allow them to bring laws, to shape institutions, and reform the opinions that govern men’s lives. Machiavelli’s armed prophet is more than a gangster; he is an educator.

Although it is characteristic of Machiavelli to talk tough—armed prophets always conquer and the unarmed always lose—he clearly recognizes that there are huge exceptions to this rule. The most obvious and important exception of an unarmed prophet conquering is Jesus Christ. Jesus conquered by words alone, which helped to establish first a sect, then a religion, and eventually an empire. Words may well be a weapon as powerful as a gun. And, then, what is Machiavelli himself but an archetypal unarmed prophet? He controls no troops or territory. Yet he is clearly attempting to conquer in large part through the transformation of our understanding of good and evil, of virtue and vice. In order to make people obey, you must first make them believe. Machiavelli’s prophetic prince must have many of the qualities of a philosopher and a religious reformer.

Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

It is often said of Machiavelli that he introduced a new kind of immoralism into politics. In his famous formula from chapter 15 he sets out to teach the prince “how not to be good.” Leo Strauss, in perhaps the most important book on Machiavelli ever written, declared him to be a “teacher of evil.”5 Questions of good and bad, virtue and vice, appear on virtually every page of The Prince. Machiavelli is not simply a teacher of pragmatism, of how to adjust the means to fit the ends; he is offering nothing short of a comprehensive reevaluation of our basic moral vocabulary of good and evil.

In order to affect his transformation of Christian morality, in order to teach the prince “how not to be good,” it is necessary to go to the source of morality. To effect the maxims that actually govern our lives, it is necessary to go to the foundation of those maxims, ones that can be found only in religion. Oddly enough, religion does not seem to be a major theme of The Prince. In a memorable passage from chapter 18, Machiavelli advises the prince to always cultivate the appearance of religion: “He should appear all mercy, all faith, all honesty, all humanity, all religion,” he writes, adding that “nothing is more necessary to appear to have than this last quality” (XVIII/70–71). The point is clear: the appearance of religion—by which he means here Christianity—is good, while the actual practice of it is harmful.

Machiavelli’s point is that if you want liberty, you have to learn how not to be good, at least as Christianity has defined goodness. The Christian virtues of humility, turning the other cheek, and forgiveness of sins must be rejected if you want to do good as opposed to just be good. You have to learn how to get your hands dirty. Between the innocence of the Christian and the worldliness of Machiavelli’s new morality, there can be no reconciliation. These are two incompatible moral positions. But Machiavelli goes further. The safety and security enjoyed by the innocent, their freedom to live blameless lives and untroubled sleep, depends entirely upon the prince’s clear-eyed and even ruthless use of power. The true statesman must be prepared to mix a love of the common good, a love of his own people, with a streak of cruelty that is often deemed essential for a great ruler in general. It is simply another example of how moral goodness grows out of and requires a context of moral evil. Machiavelli’s advice is clear: if you cannot accept the responsibilities of political life, if you cannot accept the harsh necessities that may require cruelty, deceit, and even murder, then get out of the way. Do not seek to impose your own high-minded innocence—sometimes called justice—on the requirements of statecraft, because it will only lead to ruin. In our era, the presidency of Jimmy Carter is usually taken as Exhibit A of this confusion of Christian humanitarianism with raison d’état.

In the philosophical literature this is known as the problem of dirty hands, so called after a play, Les Mains sales, written by the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. The problem of dirty hands refers to the conflict between the harsh requirements of politics and the equally demanding desire for moral purity, to keep the world at a distance. In Sartre’s play, which takes place in a fictional eastern European country during World War II, a communist resistance fighter named Hoederer upbraids an idealistic young recruit who balks at the order to carry out a political assassination. The communists are no different from members of any other party, Hoederer explains. They will do whatever they have to do to achieve victory: “How you cling to your purity, young man! How afraid you are to soil your hands! All right, stay pure! What good will it do you? Why did you join us? Purity is an idea for a yogi or a monk. Well, I have dirty hands. Right up to the elbows. I’ve plunged them in filth and blood. But what do you hope? Do you think anyone can govern innocently?”6

Or take another example: Carol Reed’s great film The Third Man. There an American innocent named Holly Martins comes to postwar Vienna to join his boyhood friend and idol, Harry Lime, who, Martins discovers, is deep inside a murderous black market racket. From a ferris wheel high above the bombed-out city, they look down on the people below, and Harry asks: “Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever? If I offered you twenty thousand pounds for every dot that stopped, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money, or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spare?” As they prepare to part, Harry provides a speech that would have done Machiavelli proud: “Under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland they had brotherly love—they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”7

Or take one more example: John Le Carré’s splendid Cold War thriller The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Here a British agent, Alec Lemas, carries on an affair with an idealistic young Englishwoman who has joined the Communist Party out of a belief in nuclear disarmament and world peace. In the course of the story, the two are used to protect an East German agent who has been turned by the English intelligence forces. After their unwitting role in the plot is made clear, Lemas explains what the world of high espionage is all about: “There’s only one law in this game, the expediency of temporary alliances. What do you think spies are? Moral philosophers measuring everything against the word of God or Karl Marx? They’re not! They’re just a bunch of seedy squalid bastards like me: little men, drunkards, queers, hen-pecked husbands, civil servants playing cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten little lives. Do you think they sit like monks in London balancing right against wrong?”8

These are all examples of what I would call faux Machiavellianism: intellectuals engaging in tough talk to show that they really have lost their idealism, the intellectual’s equivalent of losing one’s virginity. It suggests that the world is divided between the strong and the weak, between realists who see things the way they really are and the idealists who require the comfort of moral illusions.

Machiavelli does not so much reject the idea of the good as redefine it. He is continually speaking the language of virtue—actually virtù—a word which retains the Latin root for the word “man” and which translates into something like our term for manliness. What distinguishes Machiavelli’s use of this term is that he seeks to locate it in certain extreme situations such as political foundings, changes of regimes, and wars, both domestic and foreign. What distinguishes Machiavelli from his predecessors is his attempt to take the extraordinary situation—the extreme—as the normal situation and then make morality fit the extreme. His examples are typically drawn from situations in extremis where the very survival or independence of society is at stake. In such situations—and only in such situations—is it permissible to violate the precepts of ordinary morality. Machiavelli takes his bearings from such extreme states of emergency and seeks to render them normal.

Machiavelli does not deny that in ordinary times—in what we might call times of normal politics—the rules of justice may prevail. He shows only that normal politics is itself dependent on extraordinary politics—periods of crisis, anarchy, and revolution—where the normal rules of the game are suspended. It is in these times when individuals of extraordinary virtue are most likely to emerge. Machiavelli’s preference for the extreme situation expresses his belief that only in moments of great political crisis, when the very existence of society is at risk, does human nature most fully reveal itself. His writings convey a sense of urgency that evokes the necessity for the most drastic action. While the Aristotelian statesman is most likely to value stability and the means necessary to achieving it, the Machiavellian prince seeks war because only in the most extreme situations can one hope to prosper.

Machiavelli’s ethics are avowedly immoralist. What he wants the prince to value above all else are glory, fame, and honor. These are sought by the most “excellent men,” Moses, Theseus, Cyrus, and maybe Cesare Borgia, but others like Agathocles lack them. The ethic of glory is a distinctively nonmoral good. It aims not at justice, fairness, or friendship but at fostering those qualities that bring with them memorable greatness and lasting fame. These qualities Machiavelli believes are most conspicuously displayed in the world of “great politics,” specifically building up the strength of one’s city or nation for it to play a role in the game of world history. History, for Machiavelli, becomes the true court of judgment—the only final reward of virtue. Machiavelli’s advice to the prince is to create monuments for your city, make something that will be remembered, whether for good or evil. He advises citizens to take pride in the glorious achievements of their country and make their own contributions to the annals of its history.

The question that animates Machiavelli’s Prince is this. Politicians cannot serve their country unless they are prepared to dirty their hands through unscrupulous means. But how does one—how can one—preserve something like inner integrity while stooping to means—lying, character assassination, betrayal—that no decent person would employ? Machiavelli does not discuss the inner states or frames of mind of his heroes—Caesar, Hannibal, Borgia—who have chosen to get their hands dirty. What such men think of themselves, we have no idea. They perhaps have no inner life, and this is what renders them psychologically flat. Machiavelli seems to assume that the glory that comes with creating or strengthening a state is its own reward. His advice seems to be, “if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” If you don’t like the kind of person you think you might become through the demands of political life, then stay at home.

The Aesthetics of Violence

The model of Machiavellian virtù is the Renaissance statesman and general Cesare Borgia. In chapter 7 of The Prince he gives a powerful example of Borgia’s virtue in practice. Here Machiavelli tells the story of how Borgia appointed one of his lieutenants, Remirro de Orco, “a cruel and ready man,” to help organize a territory not far from the outskirts of Florence. Remirro was an efficient officer and soon established order, but Borgia, to show that he was in charge, ordered Remirro to be murdered and the body and bloody knife to be displayed in the town square. “The ferocity of this spectacle,” Machiavelli concludes, “left the people satisfied and stupefied [satisfatte e stupidi]” (VII/30).

Borgia’s use of cruelty here is an example of what Machiavelli calls “cruelty well-used”: “Those [cruelties] can be called well-used,” he writes, adding parenthetically “(if it is permissible to speak well of evil) that are done at a stroke, out of the necessity to secure oneself and then are not persisted in but are turned to as much utility for the subjects as one can” (VIII/37–38). So Machiavelli criticizes Agathocles, the tyrant of Syracuse, whose “savage cruelty and inhumanity, together with his infinite crimes, do not allow him to be celebrated among the most excellent men” (VIII/35). There can be no clearer statement of what Sheldon Wolin has called Machiavelli’s “economy of violence,” that is, the need for quick, efficient, and resolute acts of cruelty that are judged in terms of their effects alone. “What he hoped to further by his economy of violence,” Wolin writes, “was the ‘pure’ use of power, undefiled by pride, ambition, or motives of petty revenge.”9

This is at best only partially true. The term “economy of violence” says little of interest about Machiavelli, but the term “spectacle” does. He is less interested in the economy than the aesthetics of violence. He approaches politics not as an economist calculating costs and benefits but as an aesthetician concerned with the spectacular effects that violence will achieve. No one can read his descriptions of political assassination, conquest, and empire without sensing a deep admiration, even a celebration, of acts of creative violence. Thus can Machiavelli heap praise on Hannibal and his “inhuman cruelty that together with his infinite virtues always made him venerable and terrible in the sight of his soldiers” (XVII/67). But Machiavelli was not a sadist. He did not celebrate cruelty for its own sake. In a deeply revealing passage, he criticizes Ferdinand of Aragon for his acts of “pious cruelty” in expelling the Jews from Spain (XXI/88). He treated violence not as an unfortunate byproduct of political necessity but as a supreme political virtue through which form is imposed on matter.

Machiavelli’s aesthetic of violence is connected to the belief that the great civilizations in history—the Persian, the Hebrew, the Roman—all grew out of acts of cruelty, domination, and conquest. The great political leaders past and present were not monks or moral philosophers calibrating finely tuned theories of justice but men with “dirty hands” who were prepared to use instruments of deceit, cruelty, and even murder to achieve conspicuous greatness. Machiavelli takes a perverse delight in bringing out the dependence of flourishing and successful civilizations on initial acts of fratricide, murder, and civil war.

There is an often violent and usurpatory character to what Machiavelli calls virtù. Virtù is above all the ability to take advantage of a situation—the “occasion,” as Machiavelli sometimes calls it—that has been handed to us by fortuna. Virtù and fortuna are complementary terms for Machiavelli. There can be no virtue without a proper occasion in which to use it, and no occasion that does not create opportunities to exercise the proper human skills and abilities. Thus in the famous chapter 25, “How Much Fortune Can Do in Human Affairs,” Machiavelli begins by considering the proposition that so much of human life is left to chance that there is little we can do to affect the course of events. “This opinion,” he writes, with a nod to the present, “has been believed more in our times because of the great variability of things” (XXV/98).

Machiavelli considers the proposition, but rejects it. While much of what happens in politics is a matter of happenstance, luck, and sheer contingency, human intelligence, planning, and foresight still have some role to play. “In order that our free will not be eliminated,” he conjectures, “I judge that it might be true that fortune is arbiter of half our actions, but also that she leaves the other half, or close to it, for us to govern” (XXV/98). The idea is that if fortuna governs half of life, virtù has some role in shaping the other half. And in a famous image he compares fortuna to a raging current or a flood, but says that virtù, using foresight, can create artificial barriers like dams to control the uncontrollable and put in order what is by nature chaotic. It follows that those who rely or depend too much on the power of luck—like those people who live in perpetual hope that they will purchase a winning lottery ticket—will come to ruin, while those who adapt themselves to the times have a greater chance of success. This seems to be a variation of the adage that fortune favors the prepared.

But Machiavelli goes further than this. Virtù is not simply a matter of adaptation and adjustment to the circumstances. It is also a matter of forcing the circumstances to adapt to you. There is a violent and aggressive aspect to Machiavelli’s idea of adapting to the occasion. “I judge this indeed,” he writes, “that it is better to be impetuous than cautious because fortune is a woman and it is necessary, if one wants to hold her down, to beat her and strike her down” (XXV/101). In other words, fortune responds more easily to audacity than to caution, to boldness and resoluteness than to moderation. Machiavelli’s virtue is nothing if not a policy of preemption. Furthermore, Machiavelli tells the reader that such policies are more likely to find favor among the young, who he says are “less cautious, more ferocious, and command her [fortuna] with more audacity” (XXV/101).

Two Humors

What kind of government did Machiavelli think best? As he indicates at the beginning of The Prince, there are two kinds of regimes: principalities and republics. But each of these regimes is based on certain contrasting dispositions or what he calls “humors.” “For in every city,” Machiavelli writes in chapter 9, “two diverse humors are found, which arises from this: that the people desire neither to be commanded nor oppressed by the great and the great desire to command and oppress the people” (IX/39).

Machiavelli here uses a psychological, even quasi-medical term—“humors” (umori)—to designate the two great classes of people on which every state is based. Machiavelli’s theory of the two humors is reminiscent of Plato’s account of the three classes of the soul, with one vivid exception: each class in the city is bound to a “humor,” but neither humor is anchored in reason. Every state is divided into two classes, the grandi, the rich and powerful who wish to dominate, and the popolo, the common people who wish merely to be left alone, who desire neither to rule nor be ruled. One might expect the author of a book entitled The Prince to favor the great. Are not these aristocratic goals of honor and glory precisely what Machiavelli has been advocating?

Yet Machiavelli proceeds to deprecate radically the virtues of the nobility. “The end of the people,” he says, “is more decent than that of the great, since the great want to oppress and the people want not to be oppressed” (IX/39). His advice seems to be that the prince should seek to build his power base on the people rather than the nobles. Because of their ambition for power, the nobles will always be a threat to the prince, while a prince who has the people for his base can rule with greater ease and confidence. In an interesting reversal of the classical conception of politics, it is the nobles who are here said to be fickle and unreliable, while the people are more constant and stable. “The worst that a prince can expect from a hostile people is to be abandoned by it,” Machiavelli writes, “but from the great, when they are hostile, he must fear not only being abandoned but also that they may move against him” (IX/39–40).

The main business of government consists, then, in knowing how to control the great because they are always a potential source of conflict. The prince must know how to chasten the ambition—to humble the pride, as it were—of the great and powerful. This, as we will see, will be a major theme in the political philosophy of Hobbes. The rule of the prince or sovereign requires the ability to control ambition and to do so through selective policies of execution, public accusations, and political trials. Remember the example of Remirro de Orco and how his execution left the people “satisfied and stupefied.” Here is a perfect example of how both to control the ambitions of the nobles and to cater to the desires of the people.

Machiavelli’s prince, while not exactly a democrat, recognizes the essential decency of the people and the need to keep their faith. By decency Machiavelli seems to mean their absence of ambition, the absence of the desire to dominate and command. But this decency is not the same as goodness. For there is a tendency on the part of the people to descend into what Machiavelli deems “idleness” or license. The desire not to oppress others may be decent, but at the same time the people must be taught how to defend their liberty. Fifteen hundred years of Christianity have left men weak, without the capacities to exercise political responsibility or the resources to defend themselves from attack. Just as the prince must know how to control the ambitions of the nobles, he must know how to strengthen the desires of the common people.

Some readers—even some very astute readers—of Machiavelli have thought that his prince is really a kind of democrat, and that The Prince is intended precisely to alert the people to the dangers of a usurping prince. Consider Spinoza’s Political Treatise: “[Machiavelli] perhaps wished to show how careful a free people should be before entrusting its welfare to a single prince.… I am led to this opinion concerning that most far-seeing man because it is known that he was favorable to liberty.”10 Or, if you do not believe Spinoza, consider Rousseau’s comment from The Social Contract: “Machiavelli was an honest man and a good citizen; but being attached to the house of Medici he was forced during the oppression of his fatherland to disguise his love of freedom.”11

These comments are extremely revealing. Both of these great political writers take Machiavelli to be an apostle of freedom. Spinoza takes him to be offering a warning to the people about the dangers of princely rule; Rousseau takes him to have deliberately disguised his love of freedom due to the tyrannical rule of the Medici. Both regard him to be surreptitiously defending the people against the nobles.

Spinoza and Rousseau may exaggerate, but they are surely on to something. In the classical republic it is the nobility—the gentlemen possessed of wealth and leisure who are therefore capable of forming judgment—who dominate, while in Machiavelli’s state it is the people who are going to be the dominant social and political power. Machiavelli wants to redirect power away from the nobles and toward the people. Why? In the first place, he judges the people to be more reliable than the great. Once the people have been taught to value their liberty, have learned to oppose encroachments on their freedom, to be fierce and vigilant watchdogs rather than humble and subservient underlings, they will serve as a reliable basis for the greatness and power of a state. With the people on his side, the prince is more likely to achieve his goals of a robust civil life for his people and eternal glory for himself.

As Machiavelli likes to say, a prince must know how to adapt to the times. What is true for princes is no less true for their advisers like Machiavelli. One must know the nature of both princes and peoples. In the Dedication Machiavelli compares himself to a landscape painter who must place himself on top of mountains to paint the valleys and in the valleys to paint the mountains (Dedication/4). In the ancient republics it may have been necessary to find restraints on the passions of the demos, but in the modern world, where republics have become a thing of the past, the people need to be taught to value their liberty above all else. The most excellent princes of the past were those, like Moses, who brought tablets of the law and prepared their people for self-government. It is fitting that Machiavelli concludes The Prince with a chapter calling upon his countrymen to emancipate themselves and to liberate Italy from foreign intruders.

Machiavelli’s Utopianism

Let me conclude this analysis of The Prince by considering what I want to call Machiavelli’s utopianism. On the face of it, this term seems to be an oxymoron. Doesn’t Machiavelli exhort us to consider only “the effectual truth” of things, as opposed to imagined principalities, that is, to look at what people do, not at what they say, at the Is rather than the Ought? Yet despite his avowed rejection of ancient utopianism, Machiavelli tells readers to take as their models the greatest founders of peoples and nations, that these founders must be endowed with certain charismatic or prophetic properties, and that such people have come to power not through force alone but through their own virtù. These views provide evidence for an idealistic, even utopian, strain in Machiavelli’s thought.

Nowhere is Machiavelli’s idealism more on display than in the final chapter of The Prince, “Exhortation to Seize Italy and Free Her from the Barbarians.” This chapter has probably given rise to more discussion than any other part of the book. Why at the end of what to many readers seems no more than a technical, how-to manual on politics does Machiavelli conclude with a passionate call for liberation? Some readers even believe there was a gap of several years between the composition of the first twenty-five chapters of the book, written in 1513, and the final chapter. For such readers the sections of the final chapter that speak of the liberation from the barbarians and the call for the redemption of Italy could only have been written around the year 1518.12

Far from an afterthought, these reflections were an obsession of Machiavelli’s throughout all of his writings. His answer to the weakness and disunity of the Italian states was the myth of the prince: the figure personifying virtù, strength, and charisma whose redemptive power could point the way to a new Rome. In fact the opportunity for such a prince to exhibit real virtù is dependent on the current degradation of society, just as “it was necessary for anyone wanting to see the virtue of Moses that the people of Israel be enslaved in Egypt” (XXVI/102). The prophet and his people are linked. There is no such thing as a prophet without a people, or redemption without a redeemer. That Machiavelli expected such a redeemer-prince to emerge from the conditions of current decadence is clear from a letter to Vettori of August 26, 1513, during the time he was writing The Prince: “I certainly do not think that they [the Swiss] will create an empire like the Romans, but I do think they can become masters of Italy thanks to their proximity and thanks to our disarray and bad situation. And because these things appall me, I should like to remedy them … and now I am ready to start weeping with you over our collapse and our servitude that, if it does not come today or tomorrow, will come in our lifetime.”13

It is precisely out of the degradation of Italy that Machiavelli believes political redemption will follow. In fact the condition of Italy’s degradation is even necessary for the accomplishment of its eventual redemption. Like Moses, Machiavelli seems to be aware that he would not live to see the new promised land, that he was an unarmed prophet, who at best could show a new prince the way out of the wilderness and to a new Jerusalem. Machiavelli is aware that such a redeemer-prince may not come “in our time,” that the immediate future of Italy will be one of weakness and disorder, but come he will; and when he does, he will not be the prince of peace but another Borgia, Hannibal, or Alexander. Machiavelli writes to hasten the coming of this redeemer-prince. He may well have added: “May he come quickly and in our time.”

Machiavelli’s Discourses

For serious students of Machiavelli, the Discourses on Livy—the full title of the book is actually Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livy—has always been considered his most important work. In part because of its length and the organization of its subject matter, it is not read nearly so frequently as The Prince. In fact the relation between the two books has been something of an enigma for generations of readers.

The Prince was published in 1513, the year after Machiavelli was expelled from public office. The date of the Discourses is more difficult to establish. The best guess is that it was written sometime between the years 1513 and 1517, although it was not published until 1531, four years after Machiavelli’s death. Even so, he seems to have been working on both books simultaneously. In the second chapter of The Prince, he makes what seems to be an allusion to the Discourses. He remarks that The Prince will deal only with principalities and that he has saved his discussion of republics for elsewhere. That is commonly believed to be a reference to the Discourses.

Machiavelli’s statement here tells us something about the subject matter of the two books. The Prince follows the genre of the mirror of princes. It is a manual on how to achieve and maintain princely power. The Discourses is commonly regarded as Machiavelli’s book on republics. It takes the form of a historical and political commentary on the first ten books of Livy’s history of Rome, Ab Urbe Condita. Livy was widely regarded as the greatest of the Roman historians. He told the history of Rome from its founding—actually, its numerous foundings—to the establishment of the republic and the height of its power. He did not dwell (as he might have) on the descent of the republic into civil war and the transition from the republic to the monarchy under the emperors (although he wrote during the reign of Augustus). Livy’s history was always regarded as the Bible of republican government. Machiavelli, in choosing to present his teaching by means of a commentary on the greatest Roman historian, calls the reader’s attention to the greatness, the unsurpassable greatness, of Rome. Anyone who wants to understand greatness must understand Rome. Machiavelli’s turn to Rome, and especially to the history of the republic, is a signal that he sides with the ancients against the moderns and the republic against princely rule.

The Two Dedications

The difference between The Prince and the Discourses is further indicated by the dedications of the two books. The Prince is dedicated to Lorenzo de Medici. Machiavelli begins by noting that it is customary for a man of low station to dedicate his work to a person of high station. The Discourses by contrast is dedicated to two young friends of Machiavelli’s—Zanobi Buondelmonti and Cosimo Rucellai—who he says have “forced” him to write the book that he would never have written of his own accord. In what way, we wonder, was Machiavelli forced? These two young men were part of a literary circle to which Machiavelli belonged.14 More important than who they were is what they represent. Sociologically, they were members of the grandi—the aristocracy—and as such the future members of the Florentine ruling class. Machiavelli’s audience was composed of young men like Buondelmonti and Rucellai, cultured aristocrats who frequented the social gatherings in the great houses of the Italian cities, who gathered for discussions in the court of Lorenzo, and who attended productions of Roman and contemporary plays in the Orti Oricellari (Rucellai Gardens), which have been compared to the Platonic Academy. It was, apparently, under the trees in these gardens that Machiavelli first read sections of his tribute to republics to his Medicean audience!

Yet something seems amiss. Machiavelli is writing a book in praise of republics but dedicates it to two members of the aristocracy, who by their birth, education, and upbringing were bound to be deeply hostile to the cause of republican government. To be sure, Machiavelli’s best friends were members of this class. The two best known were his friend Francesco Vettori, the Florentine ambassador to Rome with whom he shared a lengthy correspondence, and the historian Francesco Guicciardini. What was he trying to accomplish? What seems clear is that he intended the Discourses as a kind of educational treatise for these young aristocrats. He presents himself as a teacher, an educator. The length and academic form of the work—a commentary on an ancient historian—would presumably have appealed to the two young Florentine humanists. In any case Machiavelli knows how to flatter his readers: “I have chosen to dedicate these, my discourses, to you in preference to all others; both because, in doing so, I seem to be showing some gratitude for benefits received, and also because I seem in this to be departing from the usual practice of authors, which has always been to dedicate their works to some prince and blinded by ambition and avarice, to praise him for all his virtuous qualities when they ought to have blamed him for all manner of shameful deeds” (Dedication/201–2).

In his dedication Machiavelli seems to be engaged in an act of self-criticism, repudiating his dedication of The Prince to Lorenzo. “So to avoid this mistake,” he continues, “I have chosen not those who are princes, but those … who deserve to be … those who know how to govern a kingdom, not those who, without knowing how, actually govern one” (Dedication/202). Machiavelli enjoys underscoring the youth of his audience. In fact book 1 of the Discourses ends with a reference to “very young men” who won triumphs for Rome. In the dedication and throughout the book, Machiavelli presents himself as a guide to the young.

Of course, Machiavelli exaggerates. If the young readers to whom the work is dedicated already knew how to govern a kingdom, then his act of writing the Discourses would appear superfluous. You don’t write a book of this length to tell people what they already know. Machiavelli insinuates himself into his readers’ good graces in order to gain their confidence. His purpose, I want to suggest, is to win over this class to the cause of republicanism, to show them the well-ordered republic so that they might create the republic that might yet be. The Discourses brings out Machiavelli’s ambition and idealism. His desire is nothing less than to create a new Rome.

“New Modes and Orders”

Machiavelli hopes to whet his readers’ appetite for Rome in the Preface to the Discourses. This is where he famously announces his discovery of “new modes and orders.” He compares himself to Columbus in a search for “new seas and unknown lands” and boasts that he has entered upon “a new way as yet untrodden by anyone else” (Preface/205). But it turns out that Machiavelli’s nautical image is the discovery not exactly of a wholly unknown land but rather of a forgotten land, a land that time has forgotten. This new land is Rome.

Machiavelli knows this claim will seem strange. He lives in a time—the Renaissance—and place—Florence—saturated with antiquity. The humanists of Machiavelli’s time were themselves imbued with love of the ancients. In order, then, to distinguish himself, Machiavelli contrasts his approach to the ancients to the aestheticizing tendency of his contemporaries in order to return his readers to the first principles of the Roman republic. Rather than praising dilettantes who collect fragments of Roman statuary to adorn their houses and gardens, Machiavelli points his readers to the actual deeds of the Romans as related by Livy: “When I notice that what history has to say about the highly virtuous actions performed by ancient kingdoms and republics, by their kings, their generals, their citizens, their legislators, and by others who have worn themselves out in their country’s service, is rather admired than imitated; nay, is so shunned by everybody in each little thing they do, that of the virtue of bygone days there remains no trace, it cannot but fill me at once with astonishment and grief” (Preface/205–6).

Machiavelli’s sarcasm is obvious. What interests his contemporaries about Rome, he implies, is its artistic style—its art and architecture. In focusing on matters of what we would call art history, they forget the most vital and important lessons, that is, the political lessons. It is important to return to Rome today, Machiavelli says, because our capacity for self-government has undergone degeneration. The moderns are inferior to the ancients in precisely those qualities that contribute to freedom. Machiavelli attributes this decline in part to Christianity, but even more to a degeneration in the art of reading. His book will be a reading lesson—a very long reading lesson—addressed to those who lack “a proper appreciation of history, owing to people failing to realize the significance of what they read, and to their having no taste for the delicacies it comprises. Hence it comes about that the great bulk of those who read it take pleasure in hearing of the various incidents that are contained in it, but never think of imitating them, since they hold them to be not merely difficult but impossible of imitation, as if the heavens, the sun, the elements of man had in their motion, their order, and their potency, become different from what they used to be” (Preface/206).

Machiavelli wants to encourage his readers not just to idly and eclectically reflect on what they read but to actively imitate the great deeds of their ancient ancestors. It is this, he says, that has led him to write a commentary on Livy. Indeed, to do full justice to the Discourses one would need to read with constant reference to Livy and to Machiavelli’s many other sources. To be sure, the Discourses is no ordinary commentary. Machiavelli uses Livy promiscuously, and for long stretches of time he disappears altogether from Machiavelli’s text. He hopes to improve upon Livy and therefore to improve upon Rome. Machiavelli will not confine himself to the study of his ancient sources alone but will constantly be “comparing ancient with modern events” in order to draw “practical lessons” from them. Let us consider some of these lessons.

Republics Ancient and Modern

The paradox at the heart of the Discourses is that Machiavelli’s claim to novelty—his nautical image of the discovery of new lands—is actually a recovery of ancient modes and orders. How does Machiavelli make something very old appear to be new and unprecedented? One answer is that he uses Livy—a respected and respectable authority—as a means to advocate for his own views on what constitutes a well-ordered republic. He hides behind Livy’s authority in order to give himself the sheen of respectability and therefore takes full advantage of the immunity of the commentator. There are four features, I want to suggest, that constitute the novelty of Machiavelli’s republic and that bear some marked resemblances to our own.

The Discourses begins with a reflection on whether it is preferable for a regime to be established by a single lawgiver or to grow haphazardly over time. The model for the former is Sparta, whose laws and constitution were given by a single man, Lycurgus, and remained intact for eight centuries. The latter model, the regime that is the product of chance—or fortuna, in Machiavelli’s language—is Rome, which lacked a single founder and was forced to refound and adapt itself to circumstances as they arose. Machiavelli presents this as something of a debate, considering the pros and cons of each side. Yet contrary to expectation, he draws a surprising conclusion: “In spite of the fact that Rome had no Lycurgus to give it at the outset such a constitution as would ensure to it a long life of freedom, yet owing to friction between the plebs and the senate, so many things happened that chance effected what had not been provided by a law-giver. So that, if Rome did not get fortune’s first gift, it got its second. For her early institutions, though defective, were not on wrong lines and so might pave the way to perfection” (I.2/215).

The claim that Rome achieved its longevity and freedom not thanks to conscious design but as a consequence of chance and luck merely paves the way for Machiavelli’s most daring and arresting thesis. It is the claim that conflict, not consensus, was what contributed most to the greatness of Rome. Not unity but disunity gave Rome its strength. Machiavelli is above all a theorist of social conflict—of class conflict—which he treats, when it is kept within bounds, as a positive good.

Machiavelli remained deeply controversial for his rejection of the model of class consensus or harmony so beloved by the humanists of his time. He returns to this theme again in book 1, chapter 4: “To me those who condemn the quarrels between the nobles and the plebs, seem to be cavilling about the very things that were the primary cause of Rome’s retaining her freedom, and that they pay more attention to the noise and clamor resulting from such commotions than to what resulted from them.… Nor do they realize that in every republic there are two different dispositions, that of the plebs and that of the nobles and that all legislation favorable to liberty is brought about by the clash between them” (I.4/218; translation modified).

This passage makes two important points. The first goes back to Machiavelli’s statement in The Prince always to look at “the effectual truth of things.” It is consequences that count, and one should not be misled by other considerations. And second, conflict is rooted deeply in human psychology, in the two “humors” or dispositions, the desire of the nobles to rule and dominate and the desire of the plebs to be free. National strength and greatness are the outcome of a clash of these opposing dispositions, not of some specious appeal to consensus. All politics is for Machiavelli partisan politics. Consensus is a fraud. Appeals to consensus are just a smokescreen for the dominance of one class. Human life is essentially an inescapable conflict. To claim that people can rise above partisanship and all embrace some idea of the common good is one of those pleasing illusions that belong to “principalities in the air.” The aim of politics should not be to eliminate conflict but to organize it and make it serve the cause of national greatness.

The second major claim of the Discourses is introduced in book 1, chapter 5, in a debate over what Machiavelli calls the “guardianship” of liberty. He asks, is power better entrusted to the people or to the nobles? Once again, he sets up the question as a debate and presents arguments from both sides. Sparta and Venice are republics that have followed the aristocratic model, lodging power within the hands of the nobility. There are good reasons for them to do this. The nobles are the class that most desire to rule, so giving them political power satisfies this desire. Also, giving power to the nobles offsets the restlessness of the plebs, who are notoriously agitated and fickle. Rome, on the other hand, is the example of a republic where power was concentrated in the plebs. It was above all the power of the people that contributed to the greatness of Rome. Although Sparta may have lasted longer, it was Rome that demonstrated greater virtue. Machiavelli sets himself firmly on the side of Rome.

Machiavelli’s preference for the plebs—the common people—is perhaps a first in political theory.15 Unlike the Aristotelian model of the politeia, or constitutional government that sought a balance of the different factions or classes, Machiavelli clearly favors the dominance of what Aristotle calls the demos. The people, Machiavelli believes, are the most reliable support of liberty. The Aristotlelian balanced constitution has become with Machiavelli a democratic republic. Machiavelli returns to this theme near the end of book 1 of the Discourses. In chapter 55 he defends republics that have established a wide degree of social equality. He goes on a tear against the nobles, who “live in idleness on their abundant revenue derived from their estates” and perform no essential labor for the republic (I.55/335). Such a class is a drain on the republic and should be eliminated. In other words, occasional purges are necessary to keep the republic pure—a lesson later adopted by the French and Russian revolutionaries who instituted bloody purges of those deemed to be “enemies of the people.” This is surely one of Machiavelli’s most bloodthirsty moments.

This argument is further developed in book 1, chapter 58, entitled “The Multitude Is Wiser and More Constant Than the Prince.” Here Machiavelli sets out his differences with Livy. Where Livy had said that the people are the most inconstant faction, Machiavelli stands this on its head. “I propose to defend a position that all writers attack,” he declares (I.58/341). Having just declared himself in favor of a bloody purge of the nobles in chapter 55, he now proclaims: “There can be no harm in defending an opinion by arguments so long as one has no intention of appealing either to authority or force” (I.58/341). It is odd that in a book designed to help us become better readers, Machiavelli seems to assume here that we have forgotten what he said just a few pages before!

Machiavelli’s arguments in defense of a democratic republic develop what he says in chapter 9 of The Prince, where he calls the people more “decent” than the prince. The people as a whole—not as any particular individual or group—reveal better judgment, more prudence, than a prince. Machiavelli develops arguments that attribute great foresight and intelligence to the people. When two speakers with equal rhetorical gifts are advocating for different positions, he asserts, the people never fail to make the right choice. I am not sure what evidence there is to support this claim. Machiavelli remarks that in the entire history of Rome, only four times—he does not say which four—did the people have cause to repent their decisions (I.58/344). Further, it is far easier to corrupt a single individual ruler than the great body of the people. In short, the people are more reliable and better judges of character than a prince. And finally, Machiavelli is prepared to excuse the brutalities of the people because, he says, they are more likely to be directed against the enemies of the republic, while the brutalities of a prince are directed against his private enemies (I.58/345).

There is one further feature of Machiavelli’s democratic republic that is worth noting. This is the Roman institution of public indictments (I.7/227–30). These were similar to people’s courts, where those accused of conspiring against the public good would have to defend themselves. Machiavelli approves the Roman practice of bringing public accusations against citizens deemed to be enemies of the people. This sounds more than a little like the practice of public denunciations during Mao’s Cultural Revolution or the infamous “show trials” under Stalin. Machiavelli approves this as an outlet for venting public hostility and also as a tool for keeping the aristocracy in check. He criticizes modern Florence for lacking such an institution, which leaves no means of chastising ambitious citizens. Note that Machiavelli says nothing about the possible injustice of such indictments. He will gladly sacrifice one person—recall Remirro d’Orco from The Prince—if it brings satisfaction to the many. In Rome public indictments were a weapon of the plebs against the rich and powerful and a chief outlet for what Machiavelli calls the “malignant humors”—jealousy, resentment, envy—to which all of us are prone.

This brings us to the fourth feature of Machiavelli’s republic. In book 1, chapter 6, Machiavelli sets out another point for the reader to consider: “Should anyone be about to set up a republic, he should first inquire whether it is to expand, as Rome did, both in dominion and in power, or is to be confined to narrow limits” (I.6/225). Traditionally, republics were understood to be small, self-contained city-states. Aristotle, recall, had praised the city that could be “taken in at a glance.” A large state undercuts the ethos necessary for political participation and civic engagement; it also encourages luxury that tends toward corruption. Machiavelli even admits that if your concern is longevity, you should follow the Spartan and Venetian models.

But after appearing to endorse the city-state model that he associated with aristocratic predominance, Machiavelli immediately goes on to undercut it. The goal of Rome was not simply longevity but greatness, and greatness is only possible with a policy of imperial expansion and conquest. Machiavelli’s republic is a republic on the march. His point is connected with the republic’s ability to control its own environment. All cities have enemies and live in the domain of fortuna; to adopt a purely defensive posture is to render oneself vulnerable to attack from others. One should therefore follow the policy of the Romans, who resolved upon empire as a means of conquering their environment and thus rendering themselves immune to the winds of fortune. They achieved this first of all by arming the plebs, which contributed to Rome’s military greatness. Arming the plebs was the source of continual tumult and dissension, but it was also the source of glory and power.

Machiavelli defends this claim with a kind of ontological argument about the nature of political reality. We live in a world of flux. States of affairs are in constant change, and the fortunes of nations constantly go up and down. A state that seeks merely to preserve itself thus risks disaster. There is no perfect balance or stable point of equilibrium to be found; therefore one has to grow and expand in order to survive. States must expand their power or face ruin—it’s that simple.

Machiavelli concludes this part of his discussion as follows: “Since it is impossible, so I hold, to adjust the balance so nicely as to keep things exactly to this middle course, one ought, in constituting a republic, to consider the possibility of its playing a more honorable role, and so to constitute it that, should necessity actually force it to expand, it may be able to retain possession of what it has acquired.… I am convinced the Roman type of constitution should be adopted and not that of any other republic, for to find a middle way between the extremes, I do not think possible” (I.6/226–27).

Machiavelli’s dismissive reference here to the “middle course” is a clear reference to Aristotle and his policy of seeking the mean or the moderate course of action. As Machiavelli suggests here, moderation is not possible in a world characterized by constant flux, because there is no stable point of equilibrium from which to measure the mean. His advice: a republic must either expand or die. Does Machiavelli’s contentious, large-scale, imperialistic republic sound familiar? It should, because Machiavelli is describing us.

The New Christianity

We cannot leave the Discourses without a word about religion—a theme that Machiavelli alludes to several times throughout the book. In the Preface he blames Christianity—he calls it “the religion of today” (what about tomorrow?)—for abetting the weakness and disunity of present-day Italy. He also refers to the evils brought about by ambition mixed with idleness, a standard form of reference to priests and their influence (Preface/206). Much of his language is that of a religious reformer—sometimes a radical reformer—much like his German contemporary Martin Luther. Yet there is a difference—a big difference.

Machiavelli is a great admirer of Numa Pompilius, the founder of the pagan religion of ancient Rome.16 “The religion established by Numa,” he writes at I.11, “was among the primary causes of Rome’s success.” What was it that Machiavelli admired? He freely acknowledges that the religion founded by Numa was a kind of fraud created to establish political virtue. Numa “pretended to have private conferences with a nymph who advised him about the advice he should give the people. This was because he wanted to introduce new institutions to which the city was unaccustomed and doubted whether his own authority would suffice” (I.11/241). In short, political innovation requires that it be shrouded in the mystique of divine authority.

The religion created by Numa is contrasted with what Machiavelli calls in the next chapter “our religion” (I.12/244). He begins this chapter by acknowledging—or pretending to acknowledge—the authority of existing religion. It is important that the prince or rulers of a republic or a monarchy uphold the principles of the religion of their state. Machiavelli takes a position of apparent neutrality toward the content of any particular religion; it is important that those in positions of political authority practice the established religion. He goes on to contrast this with the way that Christianity has historically evolved from its original teachings. “If such a religious spirit had been kept up by the rulers of the Christian commonwealth or as was ordained for us by its founder, Christian states and republics would have been much more united and much more happy than they are” (I.12/244). The cause of political decline, he says in the next sentence, can be laid at the doorstep of the Church of Rome. It is the church, more than any other institution, that has kept Italy weak and divided. “The reason why Italy is not in the same position,” he continues, “why there is not one republic or one prince ruling there is due entirely to the Church” (I.12/245). So far Machiavelli sounds like a critic of papal abuses of power, a complaint quite common and even conventional in his day.

It is not until considerably later that Machiavelli lets the cat out of the bag. In book 2, chapter 2, he asks the question, why it is that the ancients seemed more fond of liberty than the moderns? The difference, he answers, is due to the difference between our religion and theirs. It is not the corruption of Christianity that is responsible for the loss of liberty and the disunity of Italy; the problem goes back to the founding principles themselves. Machiavelli then goes on to provide a sharp and devastating series of contrasts: “Our religion has glorified humble and contemplative men, rather than men of action. It has assigned as man’s highest good humility, abnegation, and contempt for mundane things, whereas the other identified it with magnanimity, bodily strength, and everything else that conduces to make men very bold. And if our religion demands that in you there be strength, what it asks for is strength to suffer rather than strength to do bold things” (II.2/364). Here is where Machiavelli drops his bombshell:

This pattern of life, therefore, appears to have made the world weak, and to have handed it over as a prey to the wicked, who run it successfully and securely since they are well aware that the generality of men, with paradise for their goal, consider how best to bear, rather than how best to avenge, their injuries. But, though it looks as if the world were become effeminate and as if heaven were powerless, this undoubtedly is due to the pusillanimity of those who have interpreted our religion according to idleness [l’ozio] and not in terms of virtue. For, had they borne in mind that religion permits us to exalt and defend the fatherland, they would have seen that it also wishes us to love and honor it, and to train ourselves to be such that we may defend it. (II.2/364; translation modified)

What is Machiavelli saying here, and why does he wait until almost the midpoint in the book to announce it? What does he want us to do? Rather than simply advocating the reform of Christianity, he seems to be advocating the creation of a wholly new religion to replace it, in the way that Christianity once replaced the pagan Roman religion. The founder of a new republic needs to be the founder of a new religion; he should follow the example of Numa and create new rites and ceremonies from scratch. He will be a transformative, even a redemptive, leader such as Machiavelli speaks about in the final chapter of The Prince. But what would such a Machiavellian civil religion look like? Here Machiavelli is tantalizingly and, I suspect, deliberately obscure. One cannot legislate these matters in advance. This is why the founder needs constantly to read history: to see what others have done in the past so as to discover what to do and what to avoid and how to make not only a new Rome but a new Jerusalem.

Machiavellianism Comes of Age

Machiavelli’s call for the replacement of Christianity by some kind of fortified paganism did not fall on deaf ears. His most obvious disciples were those who followed the “Erastian” creed of submitting religion to political control. The most famous—or infamous—of these Erastians was Thomas Hobbes, who in both his De Cive and his Leviathan defended the proposition that religion is simply too important to be left to the priests. It must be put under secular authority. Hobbes’s goal, as we will see in the next chapter, was to establish religion on such a footing that it could not interfere with the requirements of political order.

Yet the most ferocious Machiavellian of all was Rousseau. We have already seen how Rousseau, like Spinoza, interpreted Machiavelli as providing a satire on monarchy and an esoteric defense of democracy. In the final chapter of The Social Contract, he takes up Machiavelli’s unanswered question, “What kind of religion can best serve republican government?” Like Machiavelli, and almost all who went before him, Rousseau accepted the sociological fact that “no state has ever been founded without religion serving as its base” (IV.8/146). He takes for granted the power or muscle of religion to serve as the foundation of political morality. But what kind of religion will this be? Rousseau contrasted the various polytheisms of the Greek and Roman world with the universalist monotheisms that emerged first with Judaism and later with Christianity and Islam. The pagan religions of the ancients drew no distinction between their gods and their laws. Religion could serve as a force of national strength and unity. It was also relatively tolerant, since the power of the gods extended only as far as the city walls. Even the Romans were inclined to leave peoples’ gods intact, a point with which the Jerusalemites might have taken issue. All of this changed, so Rousseau argues, with the introduction of Christianity.

Christianity was the first religion to offer itself as a purely “spiritual” kingdom apart from politics. Rousseau even has some kind words for Islam: “Muhammad had very sound views” in tying his system of law (Sharia) to his form of government. But Christianity introduced a conflict of jurisdictions between church and state, which will forever be at odds with each other. Rather than a source of unity, Christianity became a source of conflict, and religion became dominated by priests who would use it to advance their own interests. Although he recognizes that the pure religion of the Gospels contains teachings that are “saintly” and “sublime,” these are not fit for men in society. “We are told,” he writes, “that a people of true Christians would form the most perfect society imaginable. I see only one major difficulty with this supposition; which is that a society of true Christians would no longer be a society of men” (IV.8/148). He goes on to explain this point: “Christianity is a wholly spiritual religion, exclusively concerned with the things of Heaven: the Christian’s fatherland is not of this world. He does his duty, it is true, but he does it with profound indifference to the success or failure of his efforts.… True Christians are made to be slaves; they know it and are hardly moved by it; this brief life has too little value in their eyes” (IV.8/148–49).

Rousseau’s attack on “the religion of the priest” was the reason why The Social Contract was burned in his home city of Geneva. Nonetheless, the attack on “the domineering spirit of Christianity” as a cause of political conflict was widely heralded by the French revolutionaries as a basis for their new cults and rituals. These experiments with a religion of reason were short-lived, but in fact these often became in a modified form the foundation of the nationalisms of the nineteenth century, with their worship of the nation, la patrie, and the fatherland. The nation and the sovereignty of the people, as Tocqueville later saw, became substitutes for religion, or the place where religion managed to live on in a kind of ghostly half-life. Rousseau’s civil religion, which is nothing more than Machiavellianism come of age, survives today in many of the debates over the secular identity of France and its resistance to efforts—think of the debate over Muslim women wearing head scarves—by religion to intrude into public life.

Machiavelli’s dream of a new political religion that would surpass or supplant the revealed religions of the past was not confined to France. In 1967 the American sociologist Robert Bellah revived this debate in a groundbreaking article called “Civil Religion in America.”17 “What we have from the earliest years of the republic,” Bellah wrote, “is a collection of beliefs, symbols, and rituals with respect to sacred things and institutionalized in a collectivity. This religion—there seems no other word for it—while not antithetical to and indeed sharing much in common with Christianity, was neither sectarian nor in any specific sense Christian.”18 This might be called the domestication of Rousseau’s ferocious Machiavellianism. Americans, Bellah claimed, maintained a civil religion that retained key elements of the prophetic tradition but combined these with worship of the Constitution and reverence for the American Framers. “The American civil religion,” he continued, “was never anticlerical or militantly secular. On the contrary, it borrowed selectively from the religious tradition in such a way that the average American saw no conflict between the two.”19

There has been no greater avatar of this American civil religion than Abraham Lincoln. For him the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were sacred texts, and Washington and Jefferson like the prophets who led their people out of tyranny. Nowhere does Lincoln give more passionate expression to this civil creed than in his 1838 address to the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.” Shocked at the recent rise of lawlessness and the outbreaks of mob violence, Lincoln exhorted his listeners to reattach themselves to their form of government. But how to do this, he asked, at a time when the living connection to the revolution was fading, and the Founding was little more than a distant memory? His answer is as follows:

Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well wisher to his posterity, swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others. As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property and his sacred honor;—let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the character of his own, and his children’s liberty. Let reverence for the laws, be breathed by every American mother, to the lisping babe, that prattles on her lap—let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges;—let it be written in Primmers, spelling books, and in Almanacs;—let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay, of all sexes and tongues, and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.20

Lincoln’s effort to enlist the power of religion in support of the Constitution and its laws has a distinctively Machiavellian ring to it. Religion is to be made instrumental to the cause of liberty and republican government. There is nothing here with which the great Florentine would have disagreed. Are we to conclude, then, that America is a Machiavellian nation? Yes and no. The idea of an American civil religion has always remained somewhat disreputable. America may be overwhelmingly a nation of Christians, but it is not and was not intended to be a Christian nation. The attempt to enlist religion for the cause of the nation has always struck thoughtful observers as a misuse both of religion and of the patriotic ideal. The American experience is no exception. A civil religion, however ennobling its goals, is less an expression of religion than a substitute for it.