CHAPTER 9

Locke and the Art of Constitutional Government

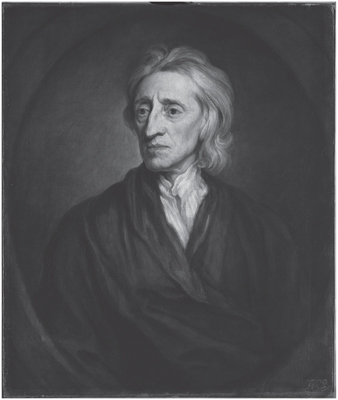

John Locke, 1632–1704. 1697. Oil on canvas. Portrait by Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723). Photo credit: bpk, Berlin / State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg / Roman Beniaminson / Art Resource, NY

John Locke gives the modern state the expression that is most familiar to us. His writings seem to have been so completely adopted by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence that Locke is often thought of as almost an honorary member of the American founding generation. Among other things, he advocates the natural liberty and equality of human beings; the individual’s right to such things as life, liberty, and property; government by consent; limited government with a separation of powers; and a right to revolution. In addition, Locke was an advocate of religious toleration. His name is forever linked to the idea of liberal or constitutional democracy.1

Yet Locke’s teachings did not arise ex nihilo. They were prepared in part by Machiavelli, who died approximately a century before Locke’s birth, but more importantly by Locke’s immediate predecessor, Hobbes. Hobbes had taken Machiavelli’s idea of the prince and in effect turned it into the doctrine of sovereignty. The Hobbesian sovereign is at the basis of our idea of impersonal government; Hobbes transforms princely rule into an office which is at once a creation of a social contract or “covenant” and responsible to the agents or persons who have created the contract. Hobbes had taught that the sovereign is representative of the people who create this office in order to ensure peace, justice, and order. Without the power of the sovereign, we would find ourselves in a state of nature—a term coined by Hobbes to indicate a world without civil authority. Hobbes gives voice to the doctrine of secular absolutism, one that invests the sovereign with virtually unlimited power to do whatever is necessary to ensure peace and stability.

Out of such harsh and formidable premises grew Locke’s new, more liberal constitutional theory of the state. Locke set out to tame or domesticate Hobbes, whose theory of absolute government found few immediate defenders. Locke’s most important work of political theory is the Two Treatises of Civil Government. The First Treatise was an elaborate and painstaking refutation of the theory of the divine right of kings advocated by Sir Robert Filmer in a book called Patriarcha. Here Locke demolishes the claim that kingship derives from God’s grant of dominion to Adam and hence that all authority is acquired by divine right. The First Treatise is an important but long and tedious work that even Locke must have found tiresome. It is in the Second Treatise, written we now believe shortly before the Glorious Revolution of 1688, that Locke advanced his bold and innovative ideas on the role of government.

Locke’s Second Treatise was intended as a practical work, addressed not so much to philosophers as to Englishmen, in the everyday language of his time. Locke wrote to capture the common sense of his age, although this is not to say that he was not extremely controversial. He was a deeply political man, although a cautious and reticent one, who lived in a period of intense religious and political conflict. He was a boy when Charles I was executed and an adult when James II was overthrown and forced into exile. He spent many years at Oxford, where he was suspected of harboring radical sympathies but was so cautious and careful in expressing them that even after many years the head of his college could call him “a master of taciturnity.” Locke was private secretary and physician to a man named Anthony Ashley Cooper—later Lord Shaftsbury—who formed a circle of radical opponents to the monarchy. Locke was forced into exile in 1683 and lived in Holland for several years before returning to England, where he remained until his death in 1704. At the time of his death he was the most famous philosopher in Europe.

Locke’s Bestiary

More than any other modern thinker, Locke makes the natural law the centerpiece of his political theory. To understand the natural law, it is necessary to see it in the natural condition, the state of nature. For Locke the state of nature is not a condition of ruling and being ruled as it was for Aristotle but one of “perfect freedom” (II/4). While Aristotle understood that by nature we are members of a family, a polis, a moral community of some sort bound by ties of obligation, Locke means this as a condition without civil authority or civil obligation. The state of nature is not an actual historical state—although Locke sometimes compares the state of nature to the vast tracts of North America—but a kind of thought experiment. What is human nature, Locke asks, in the absence of all authority?

On the surface Locke’s state of nature seems the virtual antithesis of Hobbes’s. The state of nature is not an amoral condition of violence and murder, as Hobbes had opined. The state of nature is a moral condition governed by a moral law that dictates peace and sociability. This law “willeth the peace and preservation of all mankind” (II/7).

Locke’s natural law seems like a traditional form of moral law that would have been familiar to readers of Cicero, Thomas Aquinas, and Richard Hooker (“the judicious Hooker”). It sounds very comforting and traditional. All civil authority has its foundation in a law of nature that is knowable to all human beings by virtue of their reason alone. The law of nature declares that as we are all the “Workmanship” of “one Omnipotent and infinitely wise Maker,” we ought never to harm any others in their lives, liberties, or possessions (II/6). Locke seems to weave together effortlessly the Stoic tradition of natural law and the Christian conception of divine workmanship into one seamless whole.

But even within the opening paragraphs, Locke’s law of nature turns into a right of individual self-preservation. From the beginning it is not altogether clear whether the natural law is a theory of moral duties and obligations toward others or a Hobbesian doctrine of natural right that mandates that priority be given to individual self-preservation and what is necessary to achieve it. The state of nature is a condition without civil authority. The law of nature has no person or office to oversee its application. The state of nature, at first described as a condition of peace and mutual trust, quickly degenerates into a state of war, with every individual serving as the judge, jury, and executioner of the natural law. The state of nature quickly has become a Hobbesian condition of every man for himself: “The damnified Person has this Power of appropriating to himself, the Goods or Services of the Offender by Right of Self-preservation, as every Man has a Power to punish the Crime, to prevent its being committed again, by the Right he has of Preserving all Mankind, and doing all reasonable things he can in order to that end” (II/11).

The “Fundamental law of Nature,” as Locke calls it, is the right of self-preservation, which states that each person is empowered to do whatever is in his power to do to preserve himself. “And one may destroy a Man who makes War upon him, or has discovered an Enmity to his being, for the same Reason that he may kill a Wolf or a Lyon; because such Men are not under the ties of the Common Law of Reason, have no other Rule, but that of Force and Violence and so may be treated as Beasts of Prey, those dangerous and noxious Creatures that will be sure to destroy him, whenever he falls into their Power” (III/16).

One might call this Locke’s bestiary. The state of nature is a condition populated not by gentle, peace-seeking, and cooperative persons but by various “Beasts of Prey” of all descriptions—lions, tigers, and bears. The very freedom that such beings enjoy in the state of nature leads to its abuse, which in turn requires the need for government. In the meantime, however, is the state of nature—as Locke initially asserts—a moral condition overseen by a natural law of peace or is it a thinly veiled description of a Hobbesian war of all against all?

Locke seems to be speaking two different languages: one of traditional natural law that posits duties to others, and the second of a modern Hobbesian conception of natural right that maintains the priority of rights, especially the right to one’s self-preservation. Is Locke a member of the Ciceronian and Thomistic natural law tradition or a modern Hobbesian? Do his politics derive from a theological conception of divine “workmanship” or from an ultimately naturalistic account of the human passions and the struggle for survival? These are the questions that have long bedeviled readers of the Second Treatise.

Some readers argue that Locke’s idea of equality in the state of nature relies specifically upon a Christian context of argument.2 His statement that “there being nothing more evident, than that Creatures of the same species and rank, promiscuously born to all the same advantages of Nature, and the use of the same faculties, should also be equal one amongst another” (II/4) is said to rely on an idea of God’s workmanship. What it means to belong to a species and why belonging to the same species confers a special rank and dignity on its members only makes sense if one believes that the species in question has a specifically moral relation to God. In the end, as I will try to show later, it is not the theological conception of divine “workmanship” but the utterly worldly and secular doctrine of “self-ownership” that best characterizes Lockean political philosophy.

The question of whether Locke’s idea of natural law relies upon theological belief or whether it can be inferred from nontheological, purely naturalistic grounds is not simply a philosophical problem. If we consider that Locke’s doctrine about natural law forms an important support of the Declaration of Independence, how we interpret his thought will carry major implications for how we think about a host of public policy issues. For example, the Declaration’s reference to “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” seems to come right out of the Second Treatise. But if the laws of nature are underwritten by “Nature’s God,” this has major implications for issues such as school prayer and the display of the Ten Commandments in courthouses and other public spaces. To what extent do our rights and duties depend upon a theological conception of nature and human nature? How one thinks about this issue will often determine the place, if any, of religion in the public arena.

Let us consider this question by examining Locke’s most characteristic doctrine: his theory of property.

“The Labour of his Body”

The core of Locke’s theory of government is arguably lodged in his account of property in chapter 5 of the Second Treatise. Locke’s conception of human nature is very much that of man as the property-acquiring animal. Our claims to property derive from our own work; the fact that we have expended our labor on something gives us the title to it. Labor is the source of all value. The state of nature is a condition of communal ownership—what Marx would have called primitive communism. The fact that we add our labor to something marks it off as ours: “Every man has a Property in his Person. This no Body has any Right to but himself. The Labour of his Body and the Work of his Hands, we may say, are properly his.… For this Labour being the unquestionable Property of the Laborer, no Man but he can have a right to what that is once joyned to, at least where there is enough, as good left in common for others.… That labour put a distinction between [him] and the common. That added something to them more than Nature, the common Mother of all, had done; and so they became his private right” (V/27–28).

The natural law, according to Locke, dictates a right of private property, and it is to secure this right that government is established. In a striking passage he says that the world was created in order to be cultivated and improved. Those who work to improve and develop nature are the true benefactors of mankind. “God gave the World to Men in Common,” he writes, “but since he gave it to them for their benefit, and the greatest Conveniences of Life they were capable to draw from it, it cannot be supposed he meant it should always remain common and uncultivated. He gave it to the use of the Industrious and Rational … and not to the Fancy or Covetousness of the Quarrelsome and Contentious” (V/34).

From this passage we can see at once that the Lockean state will be a commercial state. Ancient political theory regarded commerce and property as subordinate to the life of the citizen. Plato advocated communism among his Guards; Aristotle regarded the necessity of private property as a means for the few to engage in a life of politics while still being supported by a class of slaves. Economy was subordinate to polity. For Locke, however, the world belongs to “the Industrious and Rational,” namely, those people who through their own efforts increase and enhance the plenty of all. “He who appropriates land to himself by his labour,” Locke writes, “does not lessen but increase the common stock of mankind” (V/37). It is only a relatively short step from Locke’s Second Treatise to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations.3

For Locke there are no natural limits to property or acquisition. This is the absolutely essential point. Accumulation may be initially limited by use, but the introduction of money or coinage makes unlimited capital accumulation not only possible but even a moral duty (V/36). By enriching ourselves we unintentionally contribute to the benefit of others. “A King of a large and fruitful Territory [in America],” Locke writes, “feeds, lodges, and is clad worse than a day Labourer in England” (V/41). The creation of general plenty—the “common-wealth,” to use a revealing term—is due entirely to the emancipation of labor from its previous moral and political restrictions. Labor becomes the title and source of all value. In a remarkable series of rhetorical shifts, Locke makes not nature but human labor and acquisition the source of different degrees of property and material possession.

He begins the chapter with the assertion that “God hath given the world to men in common,” suggesting that the original state of nature is one of collective ownership. He then suggests that, since every person is the owner of his own body, we acquire a title to those things with which we have “mixed” our labor. But what starts as a very modest title to those objects that we have worked on ourselves, such as picking apples from a tree, soon turns into a full-scale explanation of the rise of property and a kind of market economy. Labor accounts for ten times the amount of value that is provided by nature alone, but Locke then goes on to add quickly: “I have here rated the improved land very low in making its product but as ten to one, when it is much nearer an hundred to one” (V/37). Later he even asserts that the value of anything is improved a thousandfold due to labor (V/43). What began as a fairly rudimentary discussion of the origins of property limited by the extent of use and spoilage has by the end of the same chapter turned into an account of large-scale ownership with considerable inequalities of possession. There appears to be an almost direct link between Locke’s dynamic theory of property and Madison’s claim in Federalist No. 10 that “the protection [of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property] is the first object of government.”4

Locke gives to commerce, moneymaking, and acquisitiveness not only pride of place but a moral status that such activities never enjoyed in the ancient and medieval worlds. Locke is the author of the idea that the task of government is the protection of the right of property. The new politics will no longer be concerned with glory, honor, virtue, but will be sober, pedestrian, hedonistic, though without sublimity or joy. Commerce does not require us to spill blood or risk life. It is solid, reliable, and thoroughly middle class.

The Spirit of Capitalism

The first five chapters of the Second Treatise take the form of a speculative history or anthropology of human development that walks us through the state of nature, the state of war, and the creation of property. The fifth chapter begins with a condition of primitive communism, discusses the creation of property through work, and ends with the creation of a market economy marked by vast inequalities of wealth and property. How did this occur and, what’s more important, what makes it legitimate?

Locke retells or rather rewrites the narrative of human beginnings that had previously belonged to the Bible. He tells the story of how human beings finding themselves in a state of nature without authority to adjudicate their disputes and governed only by the natural law are nevertheless able to create and enjoy the use of property acquired through “the Labour of their Body and the Work of their Hands” (V/27). Man is a property-acquiring animal even in the state of nature where there are no laws but the natural law to govern human association.

The problem, of course, with the state of nature is its instability. With no civil authority to adjudicate disputes—especially disputes over property—the peaceful enjoyment of the fruits of our labor are constantly threatened by war and conflict. How can we be secure in our person or property with no enforcement agency to resolve breaches of the peace? The need for government arises out of the real need to resolve disputes over property rights.

In many respects the very familiarity of Locke’s doctrine conceals its radicalism. Locke has made the protection of property “the great and chief end of Men’s uniting into Commonwealths” (IX/124). No one prior to Locke—I would submit—had ever believed that the purpose of politics was the protection of property rights, and by property, it should be said, Locke meant more than real estate: he meant everything that encompasses our lives, liberties, and estates. All of these are property in the literal and most revealing sense of the word: they are things that are proper to us.

Locke continually emphasizes that it is the uncertainty or “inconveniences” of the state of nature that leads us into civil association. Hobbes had emphasized the absolute fearfulness of the state of nature; for Locke it is the fact that we are beings continually beset by unease and anxiety that is the problem. It is unease—restlessness—that is both the source of our insecurities and the spur to labor and the acquisition of property.

What is it about Locke that led him constantly to emphasize the restless, uneasy, and perpetually anxious character of human nature? Certainly one never hears Plato or Aristotle refer to the fearful character of human nature. Was this an expression of Locke’s own psychological disposition that was especially prone to caution, reticence, and fearfulness? Or does his emphasis on uneasiness represent the qualities of a new class—the commercial class—seeking to establish its claim to legitimacy? When Locke writes that the world is intended for the use of the “Industrious and Rational,” he is speaking of a new middle class whose title to rule rests not on heredity or tradition or claims to nobility but on the exercise of the capacities of hard work, thrift, and opportunity. Locke’s goal in the Second Treatise seems to have been to provide this new class with a title to rule. Consider the following words of a distinguished twentieth-century commentator: “The new and politically inexperienced social classes which, during the last four centuries, have risen to the exercise of political initiative and authority, have been provided for in the same sort of way as Machiavelli provided for the new prince of the sixteenth century. None of these classes had time to acquire a political education before it came to power; each needed a crib, a political doctrine, to take the place of a habit of political behavior.… This is pre-eminently so of Locke’s Second Treatise of Civil Government.”5

Locke’s new commercial state is Machiavellianism with a human face. It is the rule not of the prince but of a new entrepreneurial middle class that operates outside the traditional sources of authority. It is the ethic, literally, of the self-made man, with all the insecurities that self-making represents. Locke’s self-made man is virtually identical to the Protestant images of the self in books like John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and the greatest single work of this genre, Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography. Locke’s account of property and the urge toward accumulation reveals the deeply Calvinist structure of his thought. His Calvinism domesticates or tranquilizes Machiavelli by turning Machiavellian virtù—manliness or daring—into the virtues of labor, industry, and hard work.

Locke’s account of our self-making, particularly our struggle to overcome the penury of nature through work and self-discipline, anticipates the genre of the “Robinsonade,” the great romance of adventure and affective individualism created by Defoe. Young Robinson Crusoe, contrary to the wishes of his father, abandons his home in England for a life of adventure and discovery abroad. A storm shipwrecks him on a deserted island where he is forced to recapitulate the experience of mankind’s struggle out of the state of nature. Severed from all social ties, he is forced back on his own resources to provide for his own self-preservation. Due to his passion for cataloguing and making use of all of the items at his disposal, Crusoe is able to re-create himself, the essence of the autonomous, self-reliant individual that would provide the model for so many of the great novels of individual self-improvement.

Defoe, like Locke, depicted the new ethic of the bourgeois class in the early stages of its vigor and optimism. They present not the warlike qualities of the martial nobility but the more homely virtues of frugality, economy, prudence, thrift, and hard work. No less an authority than Karl Marx saw in the Crusoe story the origins of the very bourgeois science of modern political economy. I cannot resist quoting at length Marx’s wonderful depiction of the Robinsonade in the first volume of Das Kapital:

Since Robinson Crusoe’s experiences are a favorite theme with political economists, let us take a look at him on his island. Moderate though he be, yet some few wants he has to satisfy, and must therefore do a little useful work of various sorts, such as making tools and furniture, taming goats, fishing and hunting. Of his prayers and the like we take no account, since they are a source of pleasure to him, and he looks upon them as so much recreation.… Necessity itself compels him to apportion his time accurately between his different kinds of work. Whether one kind occupies a greater space in his general activity than another depends on the difficulties, greater or less as the case may be, to be overcome in attaining the useful effect aimed at. This our friend Robinson soon learns by experience and having rescued a watch, ledger, and pen and ink from the wreck, commences, like a true-born Briton, to keep a set of books. His stock-book contains a list of the objects of utility that belong to him, of the operations necessary for their production; and lastly, of the labor-time that definite quantities of those objects have, on the average cost him. All the relations between Robinson and the objects that form his wealth are his own creation, are here so simple and clear as to be intelligible without exertion.… And yet those relations contain all that is essential to the determination of value.6

Lockean political philosophy gives expression precisely to what the great German sociologist Max Weber called the “the spirit of capitalism.” In his classic work The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber argued that the capitalist ethic that made a high moral duty of the limitless accumulation of capital was the outgrowth of Puritanism and Calvinism. For Weber, it was through the Protestant Reformation that took root in the countries of northern Europe that capitalism first developed, along with a wholly new moral attitude to such things as wealth and moneymaking. It would take us too far afield to examine Weber’s famous thesis about the religious origins of capitalism and the ethic of capital accumulation, but Locke seems to be exhibit A in this changed moral view toward economic activity.

Weber regarded Benjamin Franklin most of all as epitomizing the new bourgeois attitude toward wealth and capital accumulation. But rather than depicting this attitude, as had Defoe and Locke, as one of liberation from feudal hierarchies of status and tradition, Weber saw in it little more than a crabbed and colorless ethic of utilitarianism and materialism. Weber could see nothing to admire in Franklin’s ethic. It seemed to him merely a mask for hypocrisy. To view the virtues as a means to the ends of prosperity and well-being was to diminish the beauty and dignity of virtue that should be treated as an end in itself. This kind of low-minded utilitarianism was for Weber the essence of the new bourgeois creed. Franklin’s ethic represented for Weber the transformation of the Calvinist idea of a “calling” into a purely worldly ethic of success and profit seeking:

In fact, the summum bonum of this ethic, the earning of more and more money, combined with the strict avoidance of all spontaneous enjoyment of life, is above all completely devoid of any eudaimonistic, not to say, hedonistic, admixture. It is thought of as so purely as an end in itself, that from the point of view of the happiness of, or utility to, the single individual, it appears entirely transcendental and absolutely irrational. Man is dominated by the making of money, by acquisition as the ultimate purpose of his life.… At the same time it expresses a type of feeling which is closely connected to certain religious ideas. If we thus ask, why should “money be made out of men,” Benjamin Franklin himself, although he was a colorless deist, answers in his autobiography with a quotation from the Bible … “Seest thou a man diligent in his business? He shall stand before kings” (Proverbs, XXII:19).7

Weber conceives of capitalism as torn between two competing ethical ideals: one is Puritan asceticism and self-denial, the other is a eudaimonism that seeks worldly happiness through wealth accumulation and property. This tension is something that worried not only Weber but also those who have been deeply influenced by him. Leo Strauss, for example, regarded the Lockean teaching concerning property as openly “hedonist,” an “aimless” search for those things that provide satisfaction but are no longer sufficiently moored in a substantive conception of the summum bonum. “Life,” in Strauss’s famous formulation, “is the joyless quest for joy.”8 The great American sociologist Daniel Bell similarly regarded the capitalist spirit as torn between an ethic of accumulation and an ethic of consumption. These tensions constituted “the cultural contradictions of capitalism,” a contradiction between the Puritan ethic of work, discipline, and deferred gratification and a hedonistic ethic of enjoyment, pleasure, and the limitless pursuit of happiness.9 This tension still remains at the core of our capitalist system as we try to find a way to manage our contradictory impulses toward our urge to save and our urge to spend, our Calvinism and our hedonism.

It would be a mistake to think of Locke’s capitalistic revolution as due to religious sources alone. Weber struggled with the question of how a doctrine originally as morally elevated and austere as Calvin’s could morph into something like a worldly “spirit of capitalism” with its gospel of success. Even Weber was forced to admit that it was not so much Calvinism but a “corruption” of Calvinism that led its followers to see in economic well-being a sign of spiritual election. Locke was without doubt indebted to Calvinism and its Puritan offshoot in England, although he also follows secular philosophical sources initiated by Machiavelli and especially an Englishman named Sir Francis Bacon. The moral autonomy of the individual, so central to Locke’s philosophy, depends in part on Calvinist and Puritan doctrines but also on fundamental changes in the philosophical tradition that preceded by decades the writings and influence of Calvin and his acolytes.

Advise and Consent

The origin of all government—or at least all legitimate government—is said to derive from consent. In chapter 8 of the Second Treatise Locke provides a hypothetical reconstruction of the origin of all societies. “The only way whereby anyone divests himself of his Natural Liberty,” he writes in section 95, “and puts on the bonds of Civil Society is by agreeing with other Men to joyn and unite in a Community, for their comfortable, safe, and peaceable living.” Locke goes on to affirm that whenever a sufficient number of people have consented to make one community, “they are thereby presently incorporated and make one Body Politik, wherein the Majority have a right to act and conclude for the rest” (VIII/95).

This short and apparently unobtrusive statement makes the first and most powerful case for democracy. On the basis of this statement a famous Yale professor and author of an important book on Locke declared Locke to be the font of “the faith of a majority-rule democrat.”10 Locke a radical democrat? Consider the following: “For when any number of Men have, by the consent of every individual, made a Community, they have thereby made that Community one Body, with a Power to Act as one Body, which is only by the will and determination of the majority” (VIII/96). To be sure, it would have come as a surprise to the king of England or any other existing monarch to learn that he ruled only by the consent of the governed.

Is Locke denying the legitimacy of all governments that have not received the consent of the majority? This is certainly what David Hume, writing approximately half a century after Locke’s death, believed him to be saying. For Hume the doctrine of consent constituted the essence of anarchy. There was not now nor never has there been a government based on the consent of the governed, Hume argued. Government, like all institutions, rests upon habit and custom. To argue that only consent could lend legitimacy to government was to destabilize all governments: so said the Tory Hume against the Whig Locke.11

Locke did not use his theory of consent to defend democracy as the only legitimate form of government. The Second Treatise argues that government derives its just powers from the consent of the governed, but it does not specify which particular form of government is best. The majority may agree to keep political power in its own hands in which case it remains a democracy. But it may agree to be ruled by some body or even a single individual. The point seems to be that all government is elective, all government derives its power and legitimacy as a grant from the majority. Oligarchies and monarchies only exist due to the consent of the governed. Without that consent, Locke contends, even “the mighty Leviathan”—an unequivocal reference to Hobbes—could not “outlast the day it was born” (VIII/96).

Locke’s doctrine of consent could be called the cornerstone of his political theory—even more so than his doctrine of property. It is largely through Locke that the language of consent entered American political discourse. Not only did the Declaration of Independence affirm that all lawful government derives from the consent of the governed, Lincoln reaffirmed the importance of consent in the course of his struggle against slavery. Consider the following passage from his speech on the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854: “When the white man governs himself, that is self-government, but when he governs himself and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism. If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that ‘all men are created equal;’ and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.… What I do say is that no man is good enough to govern another without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle—the sheet anchor of American republicanism.”12 Lincoln’s statement here was part of his debate with Stephen Douglas over the issues of slavery, but it cut to the core of the doctrine of consent. Douglas defended the theory of “popular sovereignty” according to which whatever the majority of a people in a state or territory desired was the legitimate source of law. From this premise he could argue that slavery to him was a matter of “indifference” since it all depended on what the popular will desired. Lincoln argued otherwise. The doctrine of consent was not a blank check for majority rule. It implied a set of moral limits on what a majority can do. Consent was inconsistent with slavery because no one person can rule another without that other’s consent.

Locke was clearly aware of the radical, unsettling implications of his theory of consent. In particular, how did he believe that consent was actually conferred? We are citizens of the oldest democracy in the world, yet did anyone ever ask any of us to give our consent to our form of government? The idea of giving one’s consent to something suggests an active, emphatic voice, yet has anyone after the first generation of founders who created and ratified the Constitution ever been asked or required to give his or her consent to it? What is Locke’s answer to this problem?

Locke clearly struggles with the problem of how consent is conferred. His answer to this question is quite different from our views on citizenship. “A child,” he writes in section 118, “is born a subject of no country or Government.” In other words—and contrary to our own Fourteenth Amendment—citizenship is not conferred by birth. Every person, Locke continues, referring to his argument from the state of nature, is born free and equal and is only under the authority of his parents. Whatever government we may choose to obey is a matter not of birth but of choice.

It is only when one reaches the “Age of Discretion” that one is obligated to choose through some sign of agreement to accept the authority of government. Locke is unclear as to how this sign or act of consent is given. One suspects he is referring to some kind of oath or civil ceremony where one pledges with one’s word to accept the form of state. “Nothing can make any man so”—an actual citizen of the state—“but his actually entering into it by positive engagement and express promise and compact,” Locke writes at section 122. Such an expressed promise or agreement leaves one “perpetually and indispensably obliged to be and remain unalterably a Subject to it” (VIII/121).

One can see from this passage just how seriously Locke takes the idea of consent. One’s word is one’s bond. To give voice or consent to government is not an act to be entered into lightly but suggests a lifetime commitment. It also shows just how different Locke’s views on citizenship are from ours. For Locke, the only people to be full citizens are those who have given their active consent. The only people in our regime who have given their consent in this Lockean manner are what we call “naturalized” citizens, those who have through an official ceremony pledged their support to the form of government under which we live.

For all others, Locke contends, only a “tacit” consent has been given. But how is tacit consent conferred? How can we infer consent when it is not expressly given? This is a question that Locke does not ponder. He suggests that if we have enjoyed the safety of our person and property, one can infer our consent. When, for example, in a wedding ceremony, the minister or justice of the peace asks the congregation to “speak now or forever hold your peace,” he is asking for their consent to the legitimacy of the marriage. Generally—except in the movies—there is silence, and silence implies consent. But how do we really know under what conditions silence confers consent or when it is only silence? Silence can equally be the result of threat or intimidation. This is always the problem of inferring intention ex silentio.

“God-like Princes”

Locke’s doctrine of consent does not appear to endorse any one particular form of government. The task of forming a government will fall to the decision of the majority, but what form the majority will choose must remain an open question. What gives Locke his distinctive voice is his claim that whatever kind of government a majority decides upon, it must be one that limits the power of the sovereign.

Locke’s answer to the problem of what kind of government is best is, in a phrase, a system that checks power, especially the power of the monarch or executive. Although we typically think of the father of the doctrine of the checks and balances as the great Montesquieu, who wrote half a century after Locke, in the Second Treatise Locke spends several chapters dealing with what he calls the “subordination of powers.” His doctrine of the separation or subordination of powers is somewhat different from our own constitutional separation of executive, legislative, and judicial powers.

In the first place Locke emphasizes—in fact continually affirms—the primacy of legislative authority. He states that “the first and fundamental positive Law of all Commonwealths is the establishing of the Legislative power” (XI/134). In England this meant a doctrine of parliamentary supremacy. It is the law-making authority of government that is supreme. There is nothing more important than having settled or known laws that serve as a fence against arbitrary rule. The purpose of government is less to offset the danger of lapsing back into the state of nature (as Hobbes believed) than to prevent the possibility of a tyrant or despotic sovereign with arbitrary power over our lives and property.

Here is where we see Locke’s greatest difference with Hobbes. While Hobbes had been an unwavering defender of a united sovereign power, Locke warns continually against the dangers of too great an executive authority. In one of the few jokes to appear in the Second Treatise, Locke says the following of Leviathan: “As if when Men quitting the State of Nature entered into Society, they agreed that all of them but one, should be under the restraint of Laws, but that he should still retain all the Liberty of the State of Nature, increased with Power, and made licentious by Impunity. This is to think that men are so foolish that they take care to avoid what Mischiefs be done them by Pole-Cats, or Foxes, but are content, nay think it Safety, to be devoured by Lions” (VII/93). Here is another example of Locke’s bestiary. Hobbes had identified a real problem, but his cure was worse than the disease. Locke’s answer to Hobbes seems to be that if you thought you were bad off in the state of nature, think how much worse off you would be under the power of an absolute sovereign armed with the powers of taxation and conscription. It is not the state of nature but the use of arbitrary power that is the chief evil to be avoided.

Yet even Locke, the great constitutionalist and critic of absolutism, could not dispense entirely with the necessity for executive power. He often treats the executive—and it is not clear whether this refers to one person or a body of persons—as if it were simply an agent of the legislative power. The purpose of the executive often seems to be merely carrying out the will of the legislature. In Locke’s language, the executive power is “ministerial and subordinate to the Legislative” in its law-making capacity (XIII/153). The executive seems to be little more than a cipher in Locke’s view of legislative supremacy.

Yet there is in every community, Locke affirms, the necessity for a distinct branch of government dealing with matters of war and peace. He calls this the federative power. Every community, he affirms, is to every other community what every individual is to every other individual in the state of nature (XII/145). A distinct federative or war power is necessary in dealing with matters of international conflict between states. In a remarkable passage he notes that this power cannot be bound by “antecedent standing positive Laws” but must be left to “the Prudence and Wisdom of those whose hands it is in, to be managed for the public good” (XII/147).

In other words, matters of war and peace cannot be left to the legislature; they require the intervention of strong leadership—what Locke in an absolutely stunning turn of phrase refers to as “God-like princes” (XIV/166). It is necessary for the executive in extreme situations to call on the use of the prerogative power. “It is impossible,” Locke writes, “to foresee, and so by laws to provide for, all Accidents and Necessities, that may concern the public” (XIV, 160). During contingencies or emergencies, the executive must be empowered to act on its own initiative for the good of the community. For this reason it is necessary that the executive be entrusted with a reservoir of prerogative power that Locke defines as “the power to act according to discretion for the public good without the prescription of the Law” (XIV/160).

Locke’s prerogative power is the result of the inability of the law to foresee all possible contingencies. Our inability to make rules that can apply to all possible events makes it necessary to leave some discretionary power in the hands of the executive to act for the public safety. He gives as an example the necessity to tear down a person’s house to prevent a fire from spreading to the entire neighborhood (XIV/159). Locke’s example calls to mind certain contemporary decisions concerning the right of eminent domain. Under certain circumstances it is permissible under the laws of eminent domain for the government to seize private property for the purpose of enhancing the public welfare, for example, building a school or expanding an airport. But when do such acts become abuses of power? Is this an example of using prerogative power for the public good or an unjust usurpation of property rights? Under certain emergency circumstances, in other words, it is necessary to go beyond the letter of the law to act for the public good. The question is whether prerogative power is contained within a constitution or whether it is some kind of extraconstitutional power. And what are the limits of the executive’s prerogative power? What check, if any, is there on the use and abuse of this power?

Locke does not exactly say, yet this is a point that raises questions of fundamental importance for constitutional government. Does executive authority extend to all things in times of war, for example? Can traditional limits on presidential power (e.g., the Geneva Conventions) be curtailed under emergency circumstances or are such departures destructive of constitutional government and the rule of law? It is clear that Locke’s doctrine of prerogative power vastly expands the legitimate sphere of executive authority, as opposed to a more legalistic definition. Does Locke demonstrate to us the limits of legalism or does his advocacy of prerogative power dangerously skirt the boundless field of absolutism?

I will leave it to you to judge the extent of Locke’s prerogative power. He praises the “wisest and best princes” of England as those who exercised the largest prerogative. Such power comes into play especially during times of national crisis or emergency when the rule of law may have to be suspended for the sake of national security and protection. At such times a sovereign may find it necessary to invoke the law of nature that gives him the power to do whatever is in his power to ensure the survival of the state. Locke’s acknowledgment of a distinct power that can act on its own authority without the guidance of law is clearly in tension with his theory of legislative supremacy. His reference to “God-like princes” recalls Machiavelli’s “armed prophets” and undermines his commitment to law and limited government. Does his idea of an executive prerogative put his reputation as a founder of constitutional democracy into doubt? Was Locke aware of these paradoxes? I think so.13

Locke’s theory of prerogative power has special resonance today as we face issues of emergency (as in the wake of 9/11) and states of exception. There are some thinkers, like Carl Schmitt, the German legal theorist of the Weimar period, who believed that the state of emergency—the state of the exception—is the essence of the political and that the person or body who has the power to declare the exception is the sovereign. From Schmitt’s point of view, this is an extraconstitutional power that statesmen must necessarily utilize when ordinary constitutional operations like the rule of law prove inadequate. Such extensive power, even if it exceeds the authority granted by a constitution, is necessary to confront unforeseen situations.

But is it possible that prerogative powers are granted by our Constitution? Consider Lincoln’s decision to suspend habeas corpus during the Civil War. Lincoln did not take this extraordinary step by appealing to an extraconstitutional power that obtains in times of emergency only. He was deeply concerned about the dangers and temptations of dictatorship but argued effectively that the Constitution grants extraordinary powers to deal with extraordinary situations. He cites the Constitution: “The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety requires it.”14 In other words, the Constitution contains within itself the provision for the executive to act with prerogative power in times of rebellion or invasion, as the public safety demands. Are such arguments equally applicable to current issues relating to the detention of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay or the National Security Agency’s claims about domestic spying?

At the end of the same chapter Locke asks the question, Who shall judge—who shall arbitrate—in cases of conflict between the legislative and executive powers? He seems to be referring to moments of high constitutional crisis between conflicting powers of government. In cases of such conflict, he writes, “there can be no Judge on Earth.” “The people,” he says, “have no other remedy in this but to appeal to Heaven” (XIV/168). How much is contained in this phrase “appeal to Heaven”!

By an appeal to Heaven Locke refers to his doctrine of the right of a people to dissolve their government. He raises this question again at the very end of the book. When a conflict between the people—or their representatives—and the executive becomes so great that the very conditions of social trust have been dissolved, who shall judge? Locke answers emphatically, “The people shall be judge” (XIX/240). In other words, all power derives from and reverts back to the people.

Locke affirms a right of revolution. An appeal to Heaven refers to an appeal to arms, to rebellion, and the need to create a new social contract. He attempts to hold together a belief in the sanctity of law and the necessity for prerogative power that may sometimes have to circumvent the rule of law. Are these two compatible? Can the prerogative power of the executive be constitutionalized so that it does not threaten the liberty of its citizens? Locke alerts us to, even if he does not solve, this timeless problem.

In the end Locke was a revolutionary, but a moderate and cautious one—if this is not too much of a contradiction in terms. His doctrine of consent and legislative supremacy should make him a hero to radical democrats; his beliefs about limited government and the rights of property should make him a hero to constitutional conservatives and libertarians. Ultimately, Locke was neither and both. Like all great thinkers, he defies simple classification. But there is no doubt that he gave the modern constitutional state its definitive form of expression.

Locke’s America

No one who reads Locke can fail to recognize the profound influence his writings had on the formation of the American republic. His conception of natural law, individual rights, government by consent, and a right to revolution were the inspiration of the Declaration of Independence and other founding U.S. documents. To some degree a judgment on Locke is a judgment on America, and vice versa. He is—to the extent that anyone is—America’s philosopher-king. So what, then, should we think now just over three centuries after Locke’s death?

For many years the affiliation between Locke and America was regarded in a largely positive light. For historians and political theorists, our political stability, system of limited government, and market economy have been the result of a broad consensus on Lockean principles. But for many, this relation has also been seen as problematic. The famous historian Louis Hartz complained of America’s “irrational Lockeanism,” by which he meant a kind of closed commitment to Lockean ideals that shut off other political alternatives and possibilities. For others, Locke legitimized a narrow ethic of “possessive individualism” that focused entirely on market relations. And for still others, his emphasis on rights suggested a legalistic conception of politics that has no language for talking about the common good, the public interest, or other collective goods.15

Today, however, Locke’s theory of liberalism is confronted with another alternative that also has deep roots in the liberal tradition. I am referring to John Rawls’s widely read and widely acclaimed book A Theory of Justice.16 Rawls’s book is in many ways a contemporary attempt to update the theory of the state of nature and the social contract through the insights and techniques of contemporary philosophy and game theory. It is certainly the most important work of Anglo-American political philosophy of the past generation. It is a work that situates itself within the liberal tradition of philosophy begun by Locke but developed by Immanuel Kant and John Stuart Mill, and which Rawls hopes to put in a completed or perfected form.

Rawls’s Theory of Justice stands or falls on its theory of rights, from which all else is derived. Consider the following propositions:

Locke: “Every man has a property in his own person. This nobody has any right to but himself.” (V/27)

Rawls: “Each person possesses an inviolability founded on justice that even the welfare of society as a whole cannot override. For this reason justice denies that the loss of freedom for some is made right by a greater good shared to others.”17

So far so good. Both of these authors present theories of justice, and both justify them by recourse to liberal principles of freedom and equality. Both regard the purpose of government as securing the conditions of justice, and both regard justice as deriving from the consent—the informed consent—of the governed. But they differ profoundly over the source of rights and therefore over the role of government in securing the conditions of justice.

For Locke, rights derive from a theory of self-ownership. According to this view, everyone has a property in his or her own person, that is, no one has any claim on our bodies or our selves. On the rock of self-ownership Locke builds his edifice of natural rights, justice, and limited government. We possess an identity—what we might call moral personality—by virtue of the fact that we alone are responsible for making ourselves. We are literally the products of our own making. We create ourselves through our own activity, and our most characteristic activity is our work (“the Labour of his body and the Work of his hands, we may say, are properly his”). Locke’s doctrine is that the world is the product of our own making, of our own free activity. Not nature but the self is the source of all value. It is this self that is the unique source of rights. The task of government is to secure the conditions of our property in the broadest sense of that term, namely, everything that is proper to us.

Now contrast Locke’s theory of the source of rights to Rawls’s. Rawls adds to his conception of justice something he calls the “difference principle.” This principle maintains that our natural endowments—our talents, abilities, our family backgrounds and history, our place on the social hierarchy—are, from a moral point of view, something completely arbitrary. They are not “ours” in any strong sense, they do not belong to us, but are the result of an arbitrary genetic lottery of which each of us is the wholly undeserving beneficiary. The result is that no longer can I be regarded as the sole proprietor of my assets or the unique recipient of the advantages or disadvantages that accrue from them. Fortune—Machiavellian fortuna—is utterly arbitrary, and therefore I should be regarded not as the possessor but merely the recipient of what talents, capacities, and abilities that I may possess.

The result of Rawls’s principle—and its differences from Lockean self-ownership—could not be more striking. The Lockean theory of justice supports a meritocracy, sometimes referred to as an equality of opportunity; that is, what a person does with his or her natural assets belongs exclusively to that person. No one has the moral right to interfere with the products of our labor, which include not just the “labor of our body and the work of our hands” but also our intelligence and natural endowments. For Rawls, on the other hand, our endowments are never really our own to begin with. The capacities for hard work, intelligence, ambition, and just plain good luck do not properly belong to you at all. They are part of a common or collective possession to be shared by society as a whole. Consider the following: “The difference principle represents, in effect, an agreement to regard the distribution of natural talents as a common asset and to share in the benefits of this distribution whatever it turns out to be.”18

It is this conception of common assets that underwrites Rawls’s theory of distributive justice and the welfare state, just as it is Locke’s theory of self-ownership that justifies his conception of private property and limited government. According to Rawls’s view, justice requires that social arrangements be structured for the benefit of the “least advantaged,” that is, the worst off in the genetic lottery. For Rawls, a society is just if, and only if, it is engaged in redressing social inequalities, if it serves to benefit those whom he calls the least advantaged. Redistributing our common assets does not violate the sanctity of the individual, because the fruits of our labor were never really “ours” to begin with. Unlike Locke, whose theory of self-ownership provides a moral justification for the self, for our moral individuality, Rawls’s difference principle maintains that we never belong to ourselves alone but are always part of a “we,” a social collective whose common assets can be redistributed to the advantage of the whole.

Locke and Rawls represent two radically different visions of the liberal state, one broadly libertarian, the other broadly egalitarian, one emphasizing liberty, the other equality. Both of these views begin from certain common premises, but they move in very different directions. Locke’s theory of self-ownership regards the political community in largely negative terms as protecting our natural rights to our persons and properties; Rawls’s theory of common assets regards the community in positive terms as taking an active part in redistributing the products of our individual endeavors for the common interest. The question is which of these two views is the more valid?

My own view is that Locke is far closer to American theory and practice than is Rawls. The Declaration of Independence, the charter of American liberties, states that each individual is endowed with certain “unalienable rights,” among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The very indeterminacy of this last phrase, with its emphasis on the individual’s right to determine happiness for himself or herself, suggests a form of government that allows for ample diversity of our natural talents and abilities as well as the inequalities that derive from such diversity. Although the Declaration certainly intends the establishment of justice as one of the first tasks of government, nowhere is it implied that this requires the wholesale redistribution of our individual assets. In fact Rawls’s claim that a government is just to the extent—and only to the extent—that it is actively involved in the redress of inequalities would cast a pall of illegitimacy over virtually every government that has ever existed. This idea would also have come as news to thinkers as different as Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, Maimonides, and Thomas Aquinas, all of whom believed that social inequalities were necessary for societies to achieve a high degree of personal and collective excellence.

Also, although Rawls is clearly attentive to the moral ills of inequality, he seems naïve about the actual political mechanisms by which those inequalities will be rectified. He wants government to work for the benefit of the least advantaged, but this will require the extensive and often arbitrary use of judicial power to determine who has a right to what far in excess of limited constitutional government. At bottom are two very different conceptions of law. For Locke, laws are known rules used for the adjudication of conflicts; for Rawls, laws are the considerations of “fairness” in the distribution of scarce resources. For Rawls, laws are not simply procedures but designate substantive outcomes. Laws pertain not to rules but to regulations that certain rational competitors would agree is an equitable distribution of goods. It is not surprising that the warmest reception of Rawls’s work today has come from those advocating the modern regulatory policies whose goal is to rearrange our collective assets for the sake of achieving a maximum degree of social equality.

A return to Locke—even if such a return were possible—would by no means be a panacea for what ails us. Some historians—Louis Hartz was the most famous—treat America as a nation uniquely built upon Lockean foundations. America, Hartz believed, remained something of a Lockean remnant in a world increasingly governed by more radical forms of modernity. Indeed, it has been our stubborn Lockeanism that has prevented the kinds of extreme ideological polarization and conflict characteristic of continental Europe throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Yet the image of America as something of a theoretical anomaly protected from the shocks of later modernity cannot be sustained. Those who would urge a return to the language of Locke or the American framers are blind and deaf to later developments—romanticism, progressivism, postmodernism—that have been grafted on to the character of our regime. “The United States,” as Joseph Cropsey has argued, “is an arena in which modernity is working itself out. The founding documents are the premise of a gigantic argument, subsequent propositions in which are the decayed or decaying moments of modern thought.”19

Locke’s effort to build modern republican government on the “low but solid” ground of self-interest and the desire for comfortable self-preservation could not help but generate its own forms of dissatisfaction. Can a regime dedicated to the pursuit of happiness ever satisfy the deepest longings of the human soul? Can a regime devoted to the rational accumulation of property answer the needs for those higher-order virtues like honor, nobility, love of country, and sacrifice? Can a regime devoted to the avoidance of pain, discomfort, and anxiety produce anything more than contemporary forms of Epicureanism and nihilism? To understand the full scope of our dissatisfaction with the Lockean conception of modernity, it is important that we turn to modernity’s greatest critic: Jean-Jacques Rousseau.