CHAPTER FOUR

Drawing Lines on Sacred Land: The Dakota Treaties

Mni Sota Makoce is a rich and diverse land that gave birth to the Dakota people eons ago. As the mother and grandmother of the Dakota people, it has sustained them for countless generations. For the Dakota the land was animate, a relative, a mother. When Dakota people greet each other they often say, as Dakota historian Chris Mato Nunpa did at the beginning of a 2006 article, “Hau Mitakuyapi. Owasin cantewasteya nape ciyuzapi do!” This means, “Hello my relatives. With a good heart I greet you all with a handshake.” Particularly important in this greeting is the term mitakuyapi, or “all my relatives,” which acknowledges the central place the Dakota’s sense of living in deep and extended kinship with each other has in their culture, a meaning close to their hearts. This kinship leads Dakota to accept the obligation of attending to the well-being of their relations in a way that defines them in their interactions with each other and the land. For them, to carry out this obligation they are called upon to embody wo ohoda (respect) in their actions. This expresses a deep and pervasive sense of respect for the bonds of kinship that starts with the land that gave them birth and is their home. It is in this context that we must understand the way in which the Dakota had their lands taken from them. In the nineteenth century the Dakota were asked to sell the land and make way for its possession by another people. In the process, the deep roots of Dakota identity in Mni Sota Makoce suffered a tragic wound as the Dakota were physically driven from their homelands. This wound is carried by many Dakota people today.1

A CLASH OF STORIES

In the nineteenth century a process began through which the Dakota were dispossessed of their Minnesota homelands. Between 1805 and 1858, a period of fifty-three years, twelve treaties were concluded between the Dakota and the United States. These treaties, as understood and acted upon by the United States, had a dramatic impact on the relationship of the Dakota people with their ancestral lands in Minnesota. Where once they had ranged across the entire territory of what would become the state of Minnesota, by 1858 they had been physically confined to a small reservation ten miles wide, running 140 miles along the south shore of the Minnesota River from just east of Lake Traverse to just west of the site of the city of New Ulm.

The negotiation of these treaties was not a clear-cut process or one easily categorized. Collectively these treaties included three great cessions, comprising the Treaties of 1825, 1837, and 1851. But to call these agreements cessions is to privilege the nonindigenous side of the negotiating table. For the Dakota the word cessions might well be replaced with seizures, because of the stark contrast between the Dakota views of land and that of government negotiators, not to mention the dubious process through which these treaties were written, negotiated, and carried out.

The Dakota people and the government agents who negotiated and signed the treaties had radically different points of view about their meaning. Without understanding these differences, anything said about the treaties can be nothing more than a European projection of a far different story about the land that masks the true identity of the Dakota people. Both the Dakota and the Europeans have an intense and intimate relationship with the land, but that relationship springs from strikingly different sources of understanding. Dakota people view the land as their homeland, their relative, their mother; the Europeans see it as a possession.

Out of these two vastly different understandings have come two equally different master stories—the great stories by which a community names and explains itself and its members. The two master stories of the Dakota people and the recent European immigrants to Mni Sota who called themselves “Americans” clashed at the treaty-making table in the nineteenth century, with tragic consequences that continue down to the present day.

In a European American view, the story of the treaties between the United States and the Dakota Oyate or Nation—in individual treaties with various of the Oc̣eti Ṡaḳowiŋ, or Seven Fires—is often told as the story of U.S. westward expansion through the extension of American dominion over the Dakota homeland. This is the American story of “how the west was won and held” through warfare and politics and through the spread of European-style agriculture, forestry, mining, and urban settlement, along with the market-based commercialism that accompanied these activities. The American story also tells how, in the face of this wave of activity breaking over their homelands, Indian people were forced into a smaller and smaller territory and a correspondingly smaller range of activity on the land as they were cut off from the game and plant resources that sustained their traditional way of life. Ultimately, native people were physically separated from their homeland and confined to the small scattered areas chosen by the Europeans and called “reservations.”

Often the reservations were marked out on the least desirable land from a European American point of view. These often desolate lands lacked the resources by which the native people could live as they always had and thus compromised not only their sustenance but also their survival as a distinct people. Meanwhile, the European Americans set about to “improve” the rich land which, in their view, had been wasted by the native people. Treaties played a crucial role in the increasing separation of the Dakota from their homeland in the years between 1805 and 1858, leading up to their ultimate expulsion by military force in 1863–64.

DOCTRINE OF DISCOVERY

The Americans’ exercise of dominion over the Dakota homeland under the treaties concluded in the nineteenth century is both a product and an expression of the European Doctrine of Discovery that goes back to a series of Papal bulls issued by Pope Alexander VI in the late fifteenth century. In 1493, the year after Columbus “discovered” America, the pope issued the bull entitled In caetera Divinae, dividing the earth’s continents between Portugal and Spain. Under this bull, America was granted to Spain. It was based, in part, on Pope Innocent IV’s thirteenth-century legal commentary on an earlier decree by Pope Innocent III justifying the Christian Crusades undertaken between 1096 and 1271. The Discovery Doctrine’s foundation, under which dominion of the Christian nations of Europe was extended over the non-Christian nations of Europe and elsewhere, is rooted in the much earlier eleventh-century pronouncements on the crusades which themselves emerged from the imperial church established by Constantine after his Edict of Milan tolerating Christianity in 313. The end of persecution of the early Christian movement laid the cornerstone for the imperial church that would eventually usher in the Doctrine of Discovery. It facilitated the spread of European Christian nations’ dominion over land where such dominion had not previously existed by laying down the principle that once dominion was established by one Christian nation over such lands no other Christian nation could exercise the same right.2

The Discovery Doctrine sparked a race among the Christian nations of Europe to “discover” and “claim” lands over which no Christian nation had previously exercised dominion. Explorers set off across the seas and upon landing in new lands would, Bible in hand, plant the flags of their ruler and claim the lands against any declarations that might be subsequently made by other Christian nations. Understood from a European perspective, the doctrine authorized the “discovering” Christian nations to exercise dominion by virtue of what came to be viewed as the conquest of the non-Christian inhabitants found in the new lands. Discovery and conquest went hand in hand, laying a supposed legal foundation for the spread of European empire upon the distant lands of North America and beyond. The Discovery Doctrine provided the basis for Spanish, French, and English land claims in North America and for carving up the “discovered” land between these three European sovereign powers. Even though it was questioned by the Spanish priest Franciscus de Victoria, who in 1532 challenged the power of the Spanish crown to simply seize the indigenous peoples’ land without their consent, the conquering thrust unleashed in the fifteenth century with papal approval continued to inform the Spanish conquest and colonization of America. Eventually the Discovery Doctrine became the source of authority for non-Spanish European colonization of North America, and with the coming of the American Revolution eventually was embraced as legal precedent within the domestic law of the United States.3

The first recorded statement of a claim for the Dakota homeland in Minnesota was made under the Doctrine of Discovery in a “Minute of the taking of possession of the country of the Upper Mississippi” to include “the country of the Nadouesioux, the rivers Ste Croix and Ste Peter [later called the Minnesota River] and other places more remote,” by Nicolas Perrot on May 8, 1689. Perrot’s document was noted in the presence of several witnesses whose names are recorded and includes the fact that he had traveled “to the Country of the Nadouesioux on the border of the River Saint Croix and at the mouth of the River Saint Peter, on the bank of which were the Mantantans [sometimes called the Mdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ], and farther up into the interior to the North east of the Mississippi as far as the Menchokatoux with whom dwell the majority of the Songeskitons and other Nadoussioux, who are to the North east of the Mississippi, to take possession for, and in the name of the King [of France], of the countries and rivers inhabited by the said Tribes and of which they are proprietors.”4

Perrot’s authority for taking possession comes not from any acquiescence on the part of the Dakota or other native peoples but directly and entirely from European law and the Doctrine of Discovery, which justified the occupation of non-Christian lands. After the American Colonies broke from Britain in 1776 and the United States was established as a separate nation in 1781, the Americans increasingly became the successor beneficiaries to the perquisites gained in North America by the European Christian nations of Spain, France, and Britain under the Doctrine of Discovery. The doctrine of Manifest Destiny, an American version of the Doctrine of Discovery that envisioned westward expansion across the content, fueled extension of American dominion over indigenous land in the nineteenth century as the frontier of the new nation moved ever westward. Thus the idea that land can and is to be organized under the possession of one owner to the exclusion of all others, an old European idea that now came into American legal usage through English common law, led directly to the Louisiana Purchase of the remaining French territory west of the Mississippi River, including a portion of present-day Minnesota.

The Louisiana Purchase came about through a treaty concluded between France and the United States in Paris on April 30, 1803. By its terms France transferred to the United States 529,911,680 acres in exchange for fifteen million dollars. Following ratification of the treaty, President Thomas Jefferson was duly authorized under the established principles of domestic and international law to take possession of the newly acquired land in the name of the United States and to establish a temporary military government there. On March 10, 1804, formal ownership of Louisiana was transferred from France to the United States at a ceremony conducted in St. Louis. With this transfer the U.S. land mass doubled overnight, with the Dakota nation finding itself, without knowledge or consent, a “captive nation” within the expanded boundaries over which the United States now exercised dominion. Over the next fifty-four years, the U.S. government would negotiate with the Dakota to obtain legal ownership of all of their lands in this region to facilitate its formal transfer, parcel by parcel, to immigrant settlers under the Anglo-American rules of property law.5

In this way the United States became the successor to the Europeans who first brought the Discovery Doctrine to North America. Subsequently, this doctrine provided the basis for the U.S. Supreme Court to hold that under American law the land and sovereignty of the indigenous peoples was limited. The court took this position in a series of cases known as the Marshall Trilogy after Chief Justice John Marshall. While native peoples residing on their homelands within the expanding territorial boundaries of the United States had the right to use and occupy these lands, they no longer had the power to convey title to them. That title now rested in the United States and any of its successors to whom the land might be transferred or sold under established principles of real property law imported to the United States from England. In addition, the court held that while the “Indian nations” had some limited sovereignty to govern affairs on the land on which they resided, they did so at the pleasure and subject to the “plenary power” of Congress. Congress could, if it so chose, have the last word on how affairs were to be governed within the communities of Indian nations on their homelands. Indian nations were now defined as “domestic dependent nations,” captive within the territorial boundaries of the United States, able to exercise a limited amount of sovereignty with which the individual states could not interfere but which Congress could at any time alter by legislative action.6

From this understanding developed the Trust Doctrine, under which the federal government was held to have certain duties toward Indian nations as a guardian does to a ward, the Indian peoples being regarded as in a state of “pupilage.” The European master story viewed the indigenous peoples within the United States as defeated nations whose communities were thought to be the diminishing vestiges of a primitive, childlike, savage, warlike, and heathen race that would soon vanish from the face of the earth and/or be fully assimilated into the Christian Euro-American culture that had discovered and conquered them. This master story justified the American nation’s claim to dominion over their land, and with it the power to distribute the “free” land to the flood of European immigrants coming to the so-called new world to claim it. The indigenous people would be reduced to a small number, and their culture would disappear through assimilation. Or so it was thought.7

But this is not the only way to tell the story, and in fact it is far from complete in many senses, including a legal one. In the first place, the native peoples did not disappear, nor did their culture. Their stories of the land and the language in which those stories were told was severely stressed but not defeated, and they did not vanish as expected. In the second place, the legal assumptions that bolstered the European story were changing. The U.S. Supreme Court developed what are known as the Rules of Sympathetic Construction of Indian Treaties, a protocol for judges who interpret the treaties in cases that come before the courts. These rules recognize the disadvantage of the Indians engaged at the treaty-making table and try to compensate in the judicial interpretation of the treaties. The most important of these rules are that treaties between the United States and the Indian nations are to be (1) liberally construed in favor of the Indians “in a spirit which generously recognizes the full obligation of this nation to protect the interests of a dependent people”; (2) “in accordance with the meaning they were understood to have by the tribal representatives who participated in their negotiation” by “look[ing] beyond the written words to the larger context that frames the Treaty, including the history of the treaty, the negotiations, and the practical construction adopted by the parties”; (3) with ambiguities resolved in favor of the Indians.8

Under the Rules of Sympathetic Construction comes to light a Dakota narrative markedly different from the American narrative about the nature and function of land. When both points of view at the treaty table are understood and considered, what emerges is a complex and larger story of the negotiations as a dramatic clash of master stories evolving over the fifty-three-year span of treaty making between the Dakota and the United States, in which contrasting views of land were opposed one to the other.

It should also be noted that there were several distinctive subtexts within each of the master stories. Within the American narrative, the interests of traders, missionaries, government officials, and real-estate speculators became part and parcel of what happened at the treaty table. So did the differing points of view between Dakota traditionalists and those more willing to accept change in reaction to European American patterns of life on the frontier. These subtexts at the treaty table became a source of conflict within each of the narratives themselves. Individuals with vested interests in the treaties, such as fur traders, played prominent roles in preparations leading up to negotiations as well in the negotiations and subsequent ratification process, and the treaties became the source of internal conflicts and double-dealing by many of those involved.

PIKE’S TREATY OF 1805 AND ITS LEGACY

In September 1805 Lieutenant Zebulon Pike arrived at the island (later known as Pike Island) at the mouth of the Minnesota River at the place the Dakota called Bdote. Pike was greeted by C̣etaŋ Wakuwa Mani, also known as Petit Corbeau or Little Crow, the leader of the Kap’oża village, with a hundred and fifty warriors. The day after he arrived, on September 23, Pike, representing the United States, and the leaders of two local Dakota villages met on the island to conclude a treaty between the United States and the “Nation of Sioux Indians,” a term used to refer to the Dakota and other groups making up the Oc̣eti Ṡaḳowiŋ, or Seven Fires.9

The Dakota signers were C̣etaŋ Wakuwa Mani and Way Aga Enogee, Waŋyaga Inażiŋ (He Sees Standing Up), the chief known as Fils de Penishon, whose village was located on the lower Minnesota River.

By the wording of the treaty, the so-called Sioux Nation granted to the United States “for the purpose of the Establishment of Military Posts” two pieces of land, one at the mouth of the St. Croix River, the other to include land from below the mouth of the St. Peters or Minnesota River to the Falls of St. Anthony. According to Article 1, “the Sioux Nation grants to the United States, the full sovereignty and power over said districts forever, without any let or hindrance whatsoever.” As consideration for these grants Pike intended that the United States would pay something, but he left this line blank in the treaty. Additionally, the United States promised “to permit the Sioux to pass, repass, hunt or make other uses of the said districts, as they have formerly done, without any other exception, but those specified in article first.” In securing the agreement of the Dakota present at the council to establish military posts, Pike fulfilled specific orders for his expedition.10

On the matter of the land’s value to the United States omitted in Article 2, Pike noted in his journal that he received on behalf of the United States “about 100,000 Acres (equal to 200,000 Dollars).” Pike also reported that on the day of the council “I gave them presents to the amount of about 200 dollars, and as soon as the Council was over, I suffered the Traders [who, Pike wrote, appeared at the council as “my Gentlemen”] to present them with some liquor, which, with what I myself gave, was equal to 60 gallons.”11

The Senate did not take up the treaty until it was sent to them by President Thomas Jefferson in 1808, when they filled in the blank of Article 2 with the following language: “The United States shall, prior to taking possession thereof, pay to the Sioux two thousand dollars, or deliver the value thereof in such goods and merchandise as they shall choose.” In making this recommendation the Senate was following a committee report that put the amount of land “ceded by the Sioux” at the mouth of the St. Croix at 51,840 acres and that between St. Anthony Falls and the mouth of the Minnesota at 103,680 acres, for a total of 155,520 acres. The report went on to calculate that two thousand dollars amounted to “one cent and twenty-eight mills the acre.”12

Although President Jefferson sent the treaty to the Senate, once it was ratified he never proclaimed it, the usual final step in the process. Charles J. Kappler, who compiled the definitive collection of all treaties concluded by the United States with the various Indian nations, noted, “examination of the records of the State Department fails to indicate any subsequent action by the President [following Senate approval] in proclaiming the ratification of this treaty; but more than twenty-five years subsequent to its approval by the Senate the correspondence of the War Department speaks of the cessions of land described therein as an accomplished fact.”13

The documentary record of the 1805 treaty and its subsequent implementation gives some evidence of the clash of master stories at the treaty table, although exactly how Dakota leaders understood the treaty terms has never been completely explained. Did they appreciate the phrase “full sovereignty and power”? How was the word grant translated to them? What did they think the treaties were meant to accomplish?

Clues may be found not just in the treaty itself but in accounts of the council that took place to negotiate it and in the words and behavior of the Dakota in the years that followed. In his journal Pike stated that other Sioux chiefs were present at the treaty council, including Le Grand Partisan (possibly Wanataŋ), Le Orignal Levé (Rising or Standing Moose), Le Demi Douzen (Half Dozen or Six, Ṡakp̣e), Le Becasse (possibly a mistake for Bras Cassé, Broken Arm), and Le Boeuf qui Marche (Walking Buffalo). Pike stated that “it was somewhat difficult to get them to sign the grant, as they conceived the word of honor should be taken for the Grant, without any mark; but I convinced them that, not on their account but my own I wanted them to sign.” Some later Dakota statements about the treaty seem to suggest that the chiefs who did not sign simply did not approve of the treaty, although there is no direct evidence of this.14

In an account written on the same date as the treaty, Pike claimed he informed the Dakota that the U.S. government wished to establish military posts on the Upper Mississippi. He echoed the treaty’s wording in saying that he wished them to “grant to the United States” two parcels of land and that “as we are a people who are accustomed to have all our acts wrote down, in order to have them handed to our children—I have drawn up a form of agreement.” He stated that he would have it “read and interpreted” to them. There is no further discussion of what Pike meant by the term grant or how it was translated into Dakota. As will be seen later in relation to the Dakota Treaty of 1851 at Traverse des Sioux, the term cede was translated there with a Dakota word meaning to give up or throw away. Given the provision for the continuing use of the land by the Dakota, it is likely that such a word used for grant would have made no sense. In any case, the continuing use of the land by the Dakota contradicts the idea of the treaty as involving a sale of land. Further, Pike did go on to explain that this military post would be of benefit to the Dakota who remained around it. He stated that the Dakota’s situation would improve “by communication with the whites.” He further shared that at these posts, “factories”—usually understood to mean government-run trading posts—would be established where Indian people could get their goods cheaper than they did from their traders.15

Another stated purpose of the government-run posts was “to make peace between you and the Chipeway’s” through diplomacy. Pike wrote in his journal that he intended to take some Ojibwe and Dakota chiefs with him to St. Louis, where peace could be cemented “under the auspices of your mutual father,” meaning General James Wilkinson, then governor of the Louisiana Territory. Pike asked that the Sioux chiefs respect “the flag and protection” Pike would extend to Ojibwe chiefs who came down the river in the spring with him. He would also discourage the traders from Canada who, according to Pike, encouraged the Ojibwe to fight against the Dakota.16

In 1816 the War Department developed a plan to establish forts on the northwestern frontier, on the land described in the 1805 treaty. In an 1817 report on an expedition initiated to pursue the War Department’s plan, Major Stephen Long recommended constructing a fort at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers. The payment dictated by the U.S. Senate did not arrive in Dakota hands for fourteen years, when in 1819 Major Thomas Forsyth, Indian agent in St. Louis, traveled up the Mississippi River on instructions from the War Department, bringing a quantity of goods worth two thousand dollars, to be delivered “in payment of lands ceded by the Sioux Indians to the late Gen. Pike for the United States.” On July 25, 1819, Major Forsyth distributed some of the goods to several Sac and Fox Indians who came to him complaining that one of their brothers had been killed by a white man the previous year. Commencing August 5 at Prairie du Chien in present-day Wisconsin and ending August 26 at the juncture of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, Forsyth distributed the remainder of the goods to various Dakota tribal representatives as payment under the terms of the 1805 treaty.17

Forsyth’s payment was designed to allow the carrying out of an order from Secretary of War John C. Calhoun (after whom Lake Calhoun in Minneapolis was named) directing Colonel Henry Leavenworth to transfer the bulk of his regiment from Detroit to the juncture of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, so as to begin construction of a fort there. After wintering on the Mendota side of the Minnesota River, Leavenworth moved his encampment to the north, near the spring at what became known as Camp Coldwater. Later that year construction on Fort St. Anthony, the first name given to Fort Snelling, commenced. Leavenworth himself was not sure about the validity of Pike’s treaty, so he negotiated a new one in 1820 to accomplish the same purposes. However, his own treaty was never ratified. In June 1821 Colonel Josiah Snelling succeeded Leavenworth. Snelling redesigned the fort and construction was begun at its present location that fall.18

In the years following Fort Snelling’s construction, the Treaty of 1805 continued to be discussed in encounters between government agents and Dakota people, each of whom believed for their own reasons that it had been a legitimate treaty. In March 1829 Indian agent Lawrence Taliaferro recorded the comments of C̣etaŋ Wakuwa Mani or Little Crow, the only surviving signer of the 1805 treaty: “My Father: Since I was a small boy I have lived upon these Lands near your Fort. I gave this place to your people more than 20 years ago. My Father: I am disposed to be friendly with every body, with your Nation & our neighbours the Chippy. And Sacs & Foxes. It was allways your wish and mine also.”19

The statements are in keeping with the Dakota idea that they were giving Pike the right to build forts as a means to further the mediation between Dakota and Ojibwe and other groups. Little Crow also mentions the work of Taliaferro, Pike’s successor, in that continuing mediation.

At a meeting on June 15, 1829, Little Crow may have repeated his statement about the land on which Fort Snelling stood, because Taliaferro recorded remarks from Kaḣboka, or the Drifter, described as the second chief of the Black Dog band: “My Father I will speak a few words to you. What the Chief the Little Crow said to you this day is all true—he gave you the land on which your Fort now Stands. My Brother was on the spot at the time & knew but he is now no more for he lays among the white people—and I am sorry he did not live longer that you might have known him better.” Although Little Crow spoke that day, the remarks recorded by Taliaferro do not echo what he had said earlier. However, Taliaferro did record a speech on July 31, 1829, in which the chief stated, “My Father—I gave you the Land on which your fort Stands, if I had not been friendly disposed and wished the white people to settle near me—you would not have gotten an inch of ground from me.”20

In this period Dakota bands around Fort Snelling were concerned about both the boundaries of the land on which a military post could be built and operated and what rights the military had to the resources within and surrounding those boundaries. In September 1829 Wambdi Taŋka (Big Eagle) of Black Dog village complained to Taliaferro that trees his people needed for fencing and houses were being cut near his village. The following September Wambdi Taŋka returned to see Taliaferro and the fort’s commanding officer. Taliaferro wrote, “He wished to know the exact bounds to the U S. reserve—around Fort Snelling—& what we claim as his people wished to be immediately informed.”21

Taliaferro responded that the military reservation extended from two miles below the fort up to St. Anthony Falls and beyond for nine miles on each side of the Mississippi. This territory would extend just beyond Penichon’s village. Taliaferro stated that Henry Leavenworth had misled the Dakota about these boundaries when he negotiated the never-ratified Treaty of 1820, noting that Leavenworth “included by 4½ miles less than Pike—which oversight—has induced the Indians contiguous to this Post to aver that they only gave Pike a mile around the present site of Fort Snelling—or as they say just as far as can be seen around the Fort without elevating the eyes—which would be at the rate of two miles in some places one mile in others—where no promontory intervened it would be the greater distance 2 miles.”22

In response, Wambdi Taŋka told Taliaferro, “It is a matter of surprize to us that your Nation should come here among us poor Indians—to live hard & suffer upon this barren land. You quit a good country when you have a plenty to eat drink & to wear always with good clothes. This seems Strange to us. When the British used to see us we were better off. Our game was plenty, & our hunts good—they came but few among us—& assisted us much. I do not say this that you are to understand me as dislikeing your Nation—for we do not—but since your Nation has been here, they are catching at every thing, & times are altogether changed.“23

Taliaferro stated that he knew the chief’s feelings. The fort had not been located where it was “to injure any body much less—those whom we feel a disposition to protect.” Its purpose was protecting the fur trade and the traders “& to have proper persons in the Country to carry it on also to have a general depot to Store goods—to be divided, & sent out to different Stations for your accommodation & convenience.” The Dakota had had “many advantages both yourself & people from our location here. Much bread meat & I am assured in saying much bounty at my hands—all of which you cannot deny—but again I can assure you that we derive neither pleasure or satisfaction from our residence in your Nation, on the contrary such a long Stay has become truly irksome & disagreeable and we wish to be away from you—much worse than you do or can possibly suppose.”24

The first real survey of the Fort Snelling reservation that came into being as a result of the 1805 treaty was not done until 1839, by Lieutenant James Thompson. As shown here in a later version of the map redrawn in the 1850s, the reservation was understood to have included much of the present-day city of Minneapolis as far west as Lakes Calhoun, Harriet, and Cedar as well as portions of Bloomington and Richfield.

Shown here is a portion of a map drawn by Charles C. Royce for an 1899 Bureau of American Ethnology report recording the boundaries for land cessions covered in all of the treaties negotiated by tribes in Minnesota. The boundary at the top shows the 1825 treaty line between the Dakota and Ojibwe.

Questions about the meaning of the Fort Snelling reservation persisted. In June 1835, in a conversation with the American Fur Company trader at Mendota, Henry H. Sibley, Taliaferro referred to Pike’s treaty as not a purchase of land but a “perpetual lease.” He wrote, “M Sibley—asked how I viewed the reserve at this Post Answer—Here is the Law of June 30 1834—my opinion this rese[r]vation at S Peters is nothing more than a perpetual lease under the convention with Pike. The Treaty of 1825 (August) at Prarie du chiens confirms it. It is taken and deemed to be the Indian country in my view of the case—by the act of the 30 June 1834—as before stated.”25

This statement implies that the Treaty of 1805 was affirmed by the Treaty of 1825, a reference to Article 10 of the latter treaty which acknowledged “the general controlling power of the United States” and the existence of several reservations made under previous treaties, including one at St. Peters. Nonetheless, the questions relating to the Treaty of 1805 persisted to such an extent that the Dakota would not sign another treaty in 1837 unless a promise was made to pay some of what they considered they were owed for the earlier treaty. A total of four thousand dollars was distributed to five bands of Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ Dakota in October 1838.26

In 1837 the subject of the treaty’s meaning came up in discussions about the nature of the rights the military and civilians had in the Fort Snelling reservation. Fort commander Lieutenant Colonel William Davenport wrote the U.S. adjutant general about attempts to purchase the flour mills built by the military at St. Anthony Falls. Davenport insisted it was not in the public interest to sell the mills. Cattle imported for army use were kept at the mill before slaughter, where there were accommodations for the men who herded them and all the necessary enclosures for the cattle and hay. He interpreted Pike’s treaty as simply the Dakota’s consent to establish the fort, not a sale of land, so that the Indians never parted with the right in the soil or any other right they previously enjoyed: “Thus we are on Indian land and cannot grant any part of it to a person for private use.” Taliaferro’s point was that the land was Indian country by definition of federal law, an area where land purchases by private individuals were prohibited.27

Even after the Dakota were paid money for Pike’s Treaty in 1838 and the new treaty was signed, government correspondence refers to continuing rights under Article 3 of Pike’s treaty, “to pass, repass, hunt or make other uses of the said districts, as they have formerly done.” On April 23, 1839, Fort Snelling post surgeon John Emerson wrote to Surgeon General Thomas Lawson to complain about the presence of trader Joseph R. Brown selling whiskey within gunshot of the fort. As a solution he suggested extending the military reserve to an area twenty miles square, including the mouth of the St. Croix, “especially as the Indians are allowed by treaty to hunt on it.”28

Conflicts between the Dakota and other nearby tribes are a subtext within the larger Dakota treaty narrative. The Dakota relationship to the land included sharing that land from time to time with others, in contrast to the European American perspective that the land was a possession and property rights allowed the exclusion of others from the land. The Dakota and other nations moved back and forth through the area of Mni Sota Makoce, which the Dakota considered their sacred homeland, and the idea of drawing a boundary across it would have made little sense to them.

THE TREATY OF 1825

In August 1825, U.S. government officials met at Prairie du Chien to negotiate a “firm and perpetual peace” between the Dakota and the Ojibwe, the Sac and Fox, the Menominee, the Ioway, the Ho-Chunk, and the Odawa. The treaty attempted to establish boundaries between the lands the various nations occupied in the region of the Upper Mississippi River. For the Dakota, this involved a negotiated boundary between them and the Sac and Fox and Ioway to the south and the Ojibwe to the north. Tribes would not hunt on each other’s lands without their assent and that of the U.S. government. The various nations acknowledged the general controlling power of the United States and disclaimed all dependence upon and connection with any other power.

In 1823 Lawrence Taliaferro, as Indian agent at St. Peters, proposed that the Dakota and Ojibwe should both send delegates to Washington to negotiate a settlement and draw up a boundary. The following year Taliaferro took a party of Dakota, Ojibwe, and Menominee on the first of a series of trips to Washington, one purpose of which was to give them a chance to see something of the white man’s strength and numbers. Although no treaty was signed, the groundwork was laid for a great intertribal council at Prairie du Chien the next year.29

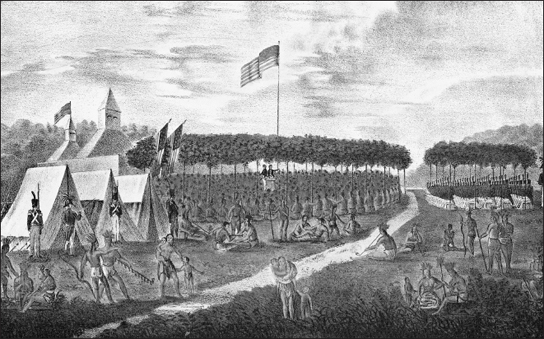

Agent Taliaferro gathered a delegation of 385 Dakota and Ojibwe of the Mississippi at Fort Snelling, including interpreters and assistants. They made their way downriver and at length halted at the Painted Rock above Prairie du Chien. After “attending to their toilet and appointment of soldiers to dress the columns of boats, the grand entry was made with drums beating, many flags flying, with incessant discharges of small arms. All Prairie du Chien was drawn out, with other delegations already arrived, to witness the display and landing of this ferocious looking body of true savages.”30

Twenty-six Dakota leaders, representing the Waḣpekute, Waḣpetuŋwaŋ, Sisituŋwaŋ, and Ihaŋktuŋwaŋ, were present at the treaty negotiation. At the beginning of the treaty council Superintendent of Indian Affairs in St. Louis William Clark told the assembled delegates that the lack of clear boundaries between nations was the cause of hostilities: “Your hostilities have resulted in a great measure from your having no defined boundaries established in your country. Your tribes do not know what belongs to them & your peoples thus follow the game into lands claimed by other tribes. This cause will be removed by the establishment of boundaries which shall be known to you & which boundaries we must establish at the council fire.”31

In fact the purpose of establishing boundaries may have been as much for facilitating treaties of cession for the lands as for establishing peace. Though the federal policy of relocating Indian tribes west of the Mississippi River was not formally passed by Congress until 1830, the Prairie du Chien treaty prepared the way for removal by establishing boundaries that would be cited in treaties ceding land in the years ahead. In light of ongoing disagreements between tribes, forcing a few tribal leaders to agree to boundaries that might or might not be respected by all tribal members certainly did not guarantee peace.

Tribal leaders knew that portions of their territory was shared, and some tried to warn the American officials that they had differing concepts of land ownership. Coramonee, a Ho-Chunk chief, said, “The lands I claim are mine and the nations here know it is not only claimed by us but by our Brothers the Sacs and Foxes, Menominees, Iowas, Mahas, and Sioux. They have held it in common. It would be difficult to divide it. It belongs as much to one as the other…My Fathers I did not know that any of my relations had any particular lands. It is true everyone owns his own lodge and the ground he may cultivate. I had thought the Rivers were the common property of all Red Skins and not used exclusively by any particular nation.”32

Similarly Noodin (the Wind), an Ojibwe leader from the St. Croix–Mille Lacs region, saw a danger in forcing the tribes to agree to a boundary: “I wish to live in peace—But in running marks round our country or in giving it to our enemies it may make new disturbances and breed new wars.” A Menominee chief named Grizzly Bear said, “We travel about a great deal and go where there is game among the Nations around who do not restrain us from doing so.” Tribal groups often made accommodations with each other and did not require a fixed boundary.33

The major disagreements at the council occurred in defining the boundaries between the Dakota, Ojibwe, and Sac and Fox. Leaders from these groups gave detailed descriptions, sometimes with the help of maps, laying out their territories. Only those Dakota leaders whose lands bordered neighboring nations demarcated their territories’ relevant boundaries, often not only naming rivers, lakes, and landmarks but noting they were born in or had long connection to these areas. The territories generally corresponded to areas where the Dakota were often described as hunting in the nineteenth century and earlier.

Wabasha, leader of the southernmost Dakota band along the Mississippi, stated that despite his claims he was willing to “relinquish some of my lands for the sake of peace.” He noted he had formerly owned the lands at Prairie du Chien but had given them up to the whites. He described a southern boundary for his land extending west of the Mississippi River from below the mouth of the Upper Iowa River to the head of the Raccoon fork of the Upper Cedar River. Beyond that, he said, “I leave for my relations to settle.”34

C̣etaŋ Wakuwa Mani or Little Crow, the surviving 1805 treaty signer, defined boundaries that bordered Ojibwe country in the north, extending from the falls of the Chippewa River to the first river above the falls of the St. Croix and up the St. Croix to Cedar Island, a day’s march above the falls at present-day Taylors Falls, Minnesota–St. Croix Falls, Wisconsin. Ṣakp̣e’s boundary lay west of that described by Little Crow. He stated that he was born on the Minnesota River and that his line “commences at Crow Island and Sandy hills on the East of the Mississippi and runs along where the timber joins the meadow to the Mississippi at the Isle [Aile] de Corbeau [Crow Wing] at the mouth of the Crow Wing River.”35

A Waḣpetuŋwaŋ leader known as the Little then spoke: “The Band of the lakes have been speaking. I am of the prairie. I claim the land up the River Corbeau [Crow River] to its source & from there to Otter Tail Lake. I can yet show the marks of my lodges there and they will remain as long as the world lasts.” Tataŋka Nażiŋ or Standing Buffalo, a Sisituŋwaŋ leader from Lake Traverse and Lac qui Parle, stated that his lands commenced at Ottertail Lake and ran north to Pine Lake and the Pine River, which emptied into the Red River. Wanataŋ, the Ihaŋktuŋwaŋ leader, said, “I am from the plains and it is of that part of our Country of which I speak. My line commences where Thick Wood River empties into Red River thence down Red River to Turtle River—up Turtle River to its source, thence south of the Devils Lake to the Missouri at the Gros Ventre Village.”36

C̣aŋ Sagye or Cane, a Waḣpekute chief whose territory overlapped with Wabasha’s on the west, stated, “I will now point out the boundary of the land where I was born. It commences at the raccoon fork of the Des Moines River at the mouth of the Raccoon River, thence up to a small lake, the source of Bear River & thence following Bear River to its entrance into the Missouri a little below Council Bluffs (suppose the Bowyer’s [Boyer] river).”37

The artist James Otto Lewis recorded the gathering of tribes at Prairie du Chien in 1825, where leaders came to sign a treaty with the U.S. government containing agreements about tribal boundaries.

Among the Ojibwe leaders, two from the Minnesota region delineated land overlapping that of the Dakota, though notably they did not claim birthright for this territory. Pee a jick [Bayezhig], or Single Man, an Ojibwe leader from Mille Lacs who also had Dakota ancestry, gave a southern boundary beginning at the mouth of the Chippewa River and extending to the head of Lake St. Croix, “thence to Green water Lake, thence to the mouth of Rum River,” across the Mississippi to the headwaters of the Crow and Sauk rivers. He said, “This is the land I claim for myself & my children hereafter.” He presented a birch-bark map showing the area. Kau ta wa be taa (Broken Tooth) of Sandy Lake claimed a line going beyond Pee a jick’s through the Crow River, to the Red River and beyond to Devils Lake.38

After some discussion, agreement was reached for a boundary between the Dakota and Ojibwe that, as historian Gary Clayton Anderson pointed out, appears to split the overlapping territory in the Minnesota region. The treaty’s wording described the boundary in terms of locations known to both nations, though identifying those exact locations today is not always easy. The eastern end of the boundary began

at the Chippewa River, half a day’s march below the falls; and from thence it shall run to Red Cedar River, immediately below the falls; from thence to the St. Croix River, which it strikes at a place called the standing cedar, about a day’s paddle in a canoe, above the Lake at the mouth of that river; thence passing between two lakes called by the Chippewas “Green Lakes,” and by the Sioux “the lakes they bury the Eagles in,” and from thence to the standing cedar that “the Sioux Split;” thence to Rum River, crossing it at the mouth of a small creek called choaking creek, a long day’s march from the Mississippi; thence to a point of woods that projects into the prairie, half a day’s march from the Mississippi.

From there the boundary continued in a diagonal line across the present state to the Red River near the mouth of “Outard or Goose creek.”39

Negotiations between the Dakota and the Sac and Fox were more difficult because of disagreements about the names given to the various forks of the Raccoon River, which involved the Waḣpekute and persisted after the treaty. The treaty also provided for further consultation with the Ihaŋktuŋwaŋ (who had not been fully represented at the negotiation) about the boundary in the area between the Des Moines and Missouri rivers.40

At the end of the negotiations, after the treaty was read and “explained to the Indians article by article,” William Clark brought out a beaded belt of wampum, such as had been used in negotiations involving Indian people and European governments in North America for hundreds of years, and sought to cast the agreement as a “religious contract between all the tribes,” represented in the belt’s patterns of beadwork. He pointed out the representation of the Great Father and the “twenty-four great fires” on the belt and offered it to the treaty signers, after which they smoked a pipe. The treaty journal does not record any responses to this aspect of the negotiation.

Although the treaty contains no cessions, it was in effect a cessional treaty for all tribes who gave up claims to land. For the Dakota the line drawn would, for all practical purposes, “cede” the northern portion of their ancestral homeland to the Ojibwe, who had come to dominate it only seventy-five years earlier when the Dakota moved out of the Mille Lacs area. As it turned out, the treaty did not have the desired effect of quelling skirmishes across the line between rival Dakota and Ojibwe bands, but it did “ratify” the Dakota’s separation from the northern reaches of their homeland that had come about as a result of the Ojibwe migration to the west. Mni Sota Makoce—the place where the Dakota dwell—had now formally become the place where the Dakota and the Ojibwe dwell.

The treaty was proclaimed by President Martin Van Buren on February 6, 1826: “The negotiations between the Sioux and the Chippewa, with which alone we are concerned, resulted in an agreement on a dividing line between their respective countries, which the Indians solemnly promised would never be crossed by either nation unless on peaceful missions.” But the treaty did not transform relations between Dakota and Ojibwe. The Dakota saw the Ojibwe pushing even beyond the agreed-upon boundaries. In June 1829, the chief of Black Dog village complained to Taliaferro, “My Father. We made peace with the Chippeways and gave them up much of our Lands—but it appears they are not satisfied with this but continue to trespass on our Lands which are bad enough & take every thing clean from the Earth as they go.” Similarly, in June 1832, Taliaferro heard several Dakota chiefs tell him, in council, “Our lands are destitute of game & our old enemies the Chippeways by constant encroachments—keep our lands so closely to themselves—ever since our treaty at Pra[i]rie du Chien that we suffer more than [can] be well conceived.”41

The Ojibwe-Dakota boundary was not surveyed until 1835, after repeated requests by the Indians. In Taliaferro’s journal for 1835 are twenty-seven entries, beginning June 10 and ending September 23, related to the survey of the “S & C Line” by Major Jonathan L. Bean, whom the Dakota called, according to Taliaferro, “Blue Cloud.” While the survey was in progress both Dakota and Ojibwe complained of the location. Taliaferro wrote to Major Bliss, commander of Fort Snelling, on August 30, 1835, that the Ojibwe would not observe the landmarks or survey markers but on the contrary had been throwing them down and attempting to demolish many of them. He predicted occasional bloodshed for the reason that, since their country was “not at all adequate to the support of their population,” the Ojibwe would force themselves on the Dakota’s hunting grounds. A few years later it was reported by a Methodist missionary that boundary mounds constructed by the surveyors “had been destroyed by the Chippewa Indians; and he was under the impression that the Chippewas were opposed to having mounds made in their country.” The missionary reported that “Indians greatly prefer natural boundary lines where the situation of the country will permit.”42

In fact, the government’s insistence that the Dakota and Ojibwe reach an agreement about an exact boundary appears to have aggravated the situation between them. Until then, the two peoples would reach yearly agreements about sharing the territory for winter hunting. Such agreements were still necessary despite the definition of the boundary line.

THE 1830 TREATY

Even if the Ojibwe-Dakota boundary had been surveyed immediately after the Treaty of 1825, however, it would probably not have brought about the stability on the frontier that Americans desired. The next attempt to resolve the issue came in 1830, when Congress passed the Removal Act, which attempted to end the ongoing conflict between the indigenous peoples and the immigrant-settlers along the frontier by removing the Indian people from their lands and moving them west. The impact of this law would be felt later in the Minnesota region than in other parts of the United States.

At Prairie du Chien in July 1830, leaders representing the Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ, Sisituŋwaŋ, Waḣpetuŋwaŋ, and Waḣpekute signed a treaty ceding a tract of country twenty miles in width, from the Mississippi to the Des Moines River, situated to the north and adjoining the line agreed upon between them and the Sac and Fox in the Treaty of 1825. This was part of a larger agreement, essentially an extension of the 1825 treaty, whereby the Dakota and the other tribes gave up their lands between the Des Moines and the Missouri for the purpose of establishing a neutral “common hunting ground” to be administered by the president of the United States. As stated in the treaty, “it is understood that the lands ceded and relinquished by this Treaty, are to be assigned and allotted under the direction of the President of the United States, to the Tribes now living thereon, or to such other Tribes as the President may locate thereon for hunting, and other purposes.” Lawrence Taliaferro took credit for this aspect of the treaty, noting “The purchase of Lands on the disputed line between the Sacs—Foxes—& the Sioux was at my instance.” He also urged that a similar agreement be reached between the Dakota and Ojibwe. Waḣpekute leader “Wiash ho ha,” who was known at the time as French Crow, stated, “You have asked for a piece of land, but you must give us $3,000 for it, and the privilege of hunting on it, and no white man must come on it.” In the end they received only two thousand dollars from the treaty, though with other benefits.43

Also at the treaty the Dakota agreed to establish a tract of land for the people of Dakota and European ancestry, beginning at Barn Bluff near Red Wing village, running back fifteen miles from the Mississippi, and then in a parallel line with Lake Pepin and the Mississippi, ending around the Grand Encampment located at one of the Wabasha village sites opposite the mouth of the Buffalo River, to be held by them “in the same manner that other Indian Titles are held.” The people to be benefited were sometimes called “half-breeds,” and the area set aside was called the “Wabasha Reservation” or the “Half-Breed Tract.” The Dakota themselves made no distinctions based on blood quantum, preferring instead to call people of such mixed ancestry with a term usually translated as “our relations”—probably from takuyapi or unkitakuyapi, versions of the word for relatives cited at the beginning of this chapter. The Wabasha Reservation was later abolished and those it was intended to benefit were issued scrip, allowing them to obtain land in other locations.44

At the 1830 negotiations Wabasha made clear that as with the neutral ground, he agreed to give up the strip of land for the mixed bloods providing the Dakota would continue to have “the privilege of hunting on it.” Other chiefs deferred to Wabasha. Little Crow—still C̣etaŋ Wakuwa Mani, the 1805 treaty signer—stated, “We say nothing about the land you spoke of. We leave that all to Wabashaw. But we have brought down a few pipes to smoke with those with whom we have made peace & to the custom of our people.” The 1830 treaty was the first treaty after Pike’s whereby the Dakota formally ceded any land to the U.S. government and the first to provide yearly payments of money in the form of annuities. The eastern Dakota received two thousand dollars a year for the period of ten years. They also were to be supplied with a blacksmith to work for them, with iron, steel, and tools from the government, as well as tools for agricultural purposes.45

THE TREATY OF 1837

The press for “cession” (which could also be called “sale”) of land by the indigenous people to the United States became a major theme in the 1830s. The first significant formal cession of Dakota land was undertaken with the Treaty of 1837 in Washington. Despite Taliaferro’s high hopes for the 1830 treaty, it did not accomplish what he had expected of it. Relations between the Dakota and the Sac and Fox worsened, as did those with the Ojibwe after the attempt to draw a boundary line in 1835. The answer, it seemed to Taliaferro, lay in another treaty, not merely to try to improve relations between the Dakota and their neighbors but also to cede lands east of the Mississippi for logging, an increasingly important industry in the region.46

Taliaferro began to think about such a treaty in late 1835. In a conversation with Major Bliss, commander at Fort Snelling, he suggested that a treaty might involve ceding Dakota lands east of the Mississippi and moving the Ho-Chunk west of the river. He noted that traders, including the American Fur Company, might try to use the agreement to seek repayment of the Dakota’s debts, something Taliaferro had successfully opposed in the Treaty of 1830. The trading companies’ claims were based on paper debts and not necessarily actual debts because for generations traders had calculated their rates of exchange of furs for merchandise to allow for the variability of fur animal populations and their customers’ ability to pay. Some had begun to give out credit to native peoples expecting to be reimbursed by the federal government. Taliaferro believed the traders would oppose the treaty until they could have him removed from his job.47

The following spring Taliaferro vowed he would leave his post once he could get such a treaty signed. He continued to write of the “rascality & frauds permitted by the treaty making power generally.” He wrote, “The Am F Cpy [American Fur Company] I say or many of its traders are disposed to stop short of nothing in getting me off from this Agency before the treaties in question are to be commenced with my Indians. But I feel doubly strong in my integrity.” In July Taliaferro warned that traders threatened or corrupted Indian people into receiving goods, forcing an “acquiescence to their diabolical plans of procuring gold out of their [natives’] hunts and mainly from the proceeds of the sales of their lands to the United States.”48

Taliaferro submitted a detailed proposal for a treaty to Superintendent William Clark in 1836, receiving a cool reception from Clark and Commissioner of Indian Affairs Elbert Herring. Later in the year, after jurisdiction of the St. Peter Agency was transferred to Governor Henry Dodge of Wisconsin Territory, the treaty was looked upon more favorably. On November 30, 1836, Taliaferro sent a new proposal to Indian Commissioner Carey A. Harris, who appeared to share the enthusiasm. Later, in July 1837, in full view of the Dakota bands, a treaty with the Ojibwe was signed at Fort Snelling, ceding Ojibwe lands east of the Mississippi River and south of the Lake Superior watershed.49

The chief negotiator for the Ojibwe treaty was Henry Dodge, who after its completion gave Taliaferro written instruction to organize two delegations of Dakota to go to Washington, one from those who lived along the boundary with the Sac and Fox, “for peace purposes,” and the other of Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ Dakota “who claim the Lands East of the Mississippi.” It was apparent the latter group would be asked to sign a treaty cession for their land, though this plan was apparently not discussed openly and it may be that the Dakota themselves were not aware of it prior to their departure. In early August, Hercules Dousman, agent of the American Fur Company at Prairie du Chien, wrote that the delegations would be going “ostensibly to make peace, but the real object is to get their Lands.” Dousman had been shown a copy of Taliaferro’s letter and had actively lobbied against the treaty. His efforts were evidence of Taliaferro’s fear that the greatest obstacles to completing the treaty would come not from the Dakota but from the American Fur Company. For this reason, officials had decided to hold the treaty negotiations in Washington, despite the logic of having them at Fort Snelling.50

Among those with a special interest in the treaty was the Mendota trader Henry H. Sibley, who was present in Washington. Sibley had particular motivation for attempting to influence the treaty negotiations. He had come to the territory in 1834, just in time to cash in at the very end of the successful fur trade and also to experience the difficulties of its decline. He soon became skilled in manipulating the engines of government for his own purposes. Sibley clearly knew of the planned treaty, if only because Taliaferro needed supplies for the delegation going to Washington. On August 16 Taliaferro purchased coats, “laced & garnished,” for ten chiefs, and a variety of other cloth, clothing, blankets, and looking glasses. Taliaferro apparently tried to mislead observers into thinking he would be leaving later than he did. Sibley wrote in mid-August to American Fur Company representatives that the delegation would not depart for Washington until September 1, at which point he would follow. Other sources suggest the delegation left around August 18. Historian Edward Neill later wrote that Taliaferro was “keeping his own council.” He engaged a steamboat captain to be at the landing at a certain date, and then “to the astonishment of the traders, the Agent, interpreters, and a part of the delegation were quickly on board, and gliding down the river.” Stops were made at Kap’oża, Red Wing, and Winona to pick up other delegation members.51

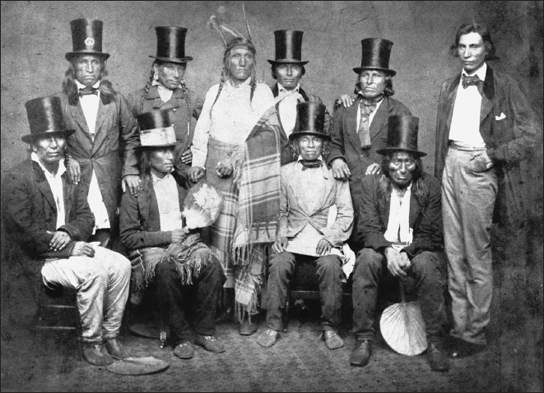

Included were at least twenty-six Dakota leaders, numbering among them not only Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ and Waḣpekute but also Sisituŋwaŋ and Waḣpetuŋwaŋ, who were not among the twenty-one who ultimately signed the treaty. The explanation for their presence comes from the instructions Taliaferro had received from Governor Dodge to bring delegations both for selling lands east of the Mississippi River and of “the Sioux on the Sac & Fox territory for peace purposes.” The various Dakota communities along the Upper Minnesota River all hunted, on occasion, along the line with the Sac and Fox. Though they did not all sign the treaty, some of them participated in its negotiation.52

On August 21, Taliaferro and his delegation reached Prairie du Chien. He wrote to Dodge at Mineral Point, stating that he intended to proceed with the delegation by way of the Ohio to Wheeling and thence to Bedford, Pennsylvania, where his wife’s family had a hotel, stating that he could “subsist my Delegation for a few days for one half less than in Washington.” He planned to wait there until Dodge arrived “with the other tribes,” probably meaning the Sac and Fox.53

Taliaferro and the delegation reached Washington on September 15, where they were boarded at the Globe Hotel. On September 20, Taliaferro outlined for fellow officials a proposed treaty that would cede all Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ Dakota lands east of the Mississippi River between the mouth of the Upper Iowa River and Watab, on the Mississippi River near the present-day town of that name. He advised that one million dollars be paid for the cession. Despite his concerns about fraud on the part of traders, Taliaferro appeared to be open to putting some such provision in the treaty, though he stated that “great care is necessary or extensive frauds will be practiced not only on the Indians but on the government.” He suggested that all claims for amounts due from the Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ to traders “be laid before the Agent and Sec. of the [treaty] Commission to prevent frauds.”54

On September 21 negotiations began at a Presbyterian church, where those not working for the government were excluded. The record of the treaty meetings provides little evidence of real negotiations. Rather it suggests that government officials had a firm idea of what they wanted based on Taliaferro’s suggestions but were unwilling to reveal the terms until well along in the process. Whether designed to keep the Dakota in the dark or to forestall the traders’ influence is not clear.55

Each day’s council was preceded by smoking a pipe passed from the treaty commissioner, Secretary of War Joel R. Poinsett, who was aided in his negotiations by Commissioner of Indian Affairs Carey Harris, to the chiefs. The commissioner began the first session by making clear the negotiations were primarily about the cession of land. He noted that the Dakota had come through “some of our great towns” and had seen “the power of the Nation.” This power would never be used to exert evil against them but only to protect them. The purpose of selling their land was to “place the great river between you and the Whites.” The hunting grounds west of the river should be sufficient for them. In return for selling their land they would be given money and things they needed. But rather than proposing terms, the commissioner indicated he was ready to receive “any proposition you may be prepared to make for that purpose.” It seems the government officials were holding their cards close to the vest, insisting that the Dakota name a price before the officials described the lands they wanted.56

The first Dakota leader to speak was Wakiŋyaŋ Taŋka, Big Thunder, son of the recently deceased Little Crow, who would later come to be known by his father’s name. He stated, “My Father, we live a great distance in the West, from the rising of the Sun. We have occupied the lands we now live on. We did not come here to learn the strength of your nation. Our friends have been here and have told us of your power.” He said they had nothing to say but would be willing to speak the following day.57

Subsequent meetings suggest government officials were reluctant to make a full proposal until they had heard what the Dakota wanted. On September 22, Ehake, a leader whose village connection was not named, spoke, stating they had no idea yet of the extent of the lands which government officials wanted. At this point the commissioner stated, “Your father will buy all of your lands East of the Mississippi for what he will pay you, one million dollars as may hereafter be agreed upon.” The Dakota responded that they wished to think over the proposition until the next day.58

At the meeting on Saturday, September 23, the commissioner began by asking the Dakota if they had an answer to the government’s offer. In response Ehake stated that they hoped he would consider that they were “naked, you are rich and well clothed.” The amount offered when divided among the Dakota would give “but little to each.” The commissioner responded that if he had not considered their needs the amount offered would not be “more than one half of the amount.” He stated, “The offer will not be changed.”59

In response Ehake noted that the recent purchase of Ojibwe lands involved “low and marshy country,” while Dakota lands were worth much more. Other leaders representing the various bands spoke, emphasizing in different ways how little the amount offered would give to each Dakota person. It was only after a Sunday break in the meetings that on September 25 the commissioner presented the details of how the one million dollars would be divided in the terms of the treaty. The largest single portion of the money would be invested to pay them a permanent annuity. Other money would be used to pay their trade debts, settle the claims of “the Half Breeds”—or those of Dakota-European ancestry—and pay for agriculture, for blacksmiths, and for presents.60

After receiving these terms, the assembled Dakota took the paper describing the division with them and spent until late afternoon discussing it among themselves. They reported they wished to keep considering the matter until they had counseled more. It appears the discussion continued until Wednesday, September 27, when the Dakota indicated they were still not in agreement about the terms. They had hoped for a higher payment but had been told that the “great council now in session” (Congress) would not accept that. The Dakota felt they were in the same situation: they were afraid “our people will not consent.” That afternoon, the Dakota leaders returned with their own proposal, apparently changing somewhat the proportions but accepting the total amount of the government’s offer. A number of chiefs spoke about their decision, after which the commissioner responded that he felt they had left out “many useful articles that they cannot well do without,” such as tobacco, salt, provisions, and stock. He said he would return with his own proposal for dividing the money.61

On September 28 several Dakota leaders, speaking in turn, asked for a further change in the provisions to the treaty, concerning the amount set aside for “our relations,” that is, the people of Dakota-European ancestry. The leaders asked that the amount be increased to $110,000. Aside from that they accepted the terms offered. Wasu Wic̣aṡtaṡni, known as Bad Hail, stated, “I addressed you the other day. I told you that I was a chief and a soldier. My father we are a part of the nation called the Seven Fires. We hope you will consent to our proposition.”62

The following day, September 29, a number of Dakota chiefs spoke about the treaty and those that preceded it. Among them was Mazamani, the Waḣpetuŋwaŋ leader from the Little Rapids village, who stated, “Since I came here I find that I have no claims to these lands. I thought I had but my friends here say that I have not. I am an old man. I shall not prevent you from buying these lands. [T]hey feel sore about parting with this country. It would bring a great price if you could cut it up and bring it here.” Ehake spoke about the land set aside for “some of our relations” in the Treaty of 1830. He pointed out that this land had not been surveyed. He asked if “you will allow us to hunt on the land we now give up to you” and said that they wished “to reserve the islands in the river so that we can go and cut wood.” He also asked that when they were paid money it should be in silver pieces. Other chiefs spoke about these and other requests. Maḣpiya Nażiŋhaŋ (Mauc peeah nasiah, Standing Cloud) noted, “We never dreamt of selling you our lands until your agent our Father invited us to come and visit our Great Father. The land that we give up to you is the best that we have. We hope you will allow us to hunt on it.”63

After the Dakota chiefs finished speaking, the commissioner presented them with the treaty for signing. Some of what they had just requested, including the right to hunt and the ownership of the islands, was not in the treaty. In fact, the treaty specifically included the islands in the land ceded. Article 1 stated that “the chiefs and braves representing the parties having an interest therein cede to the United States all their lands East of the Mississippi River and all their islands in the Said river.” From this example it is easy to conclude that the version presented for signing may not have been read or interpreted fully for the Dakota leaders.64

IMPLEMENTATION: VARIOUS PERCEPTIONS

Henry Sibley himself did not know the exact nature of the provisions in the treaty until after the signing. Writing to American Fur Company official Ramsay Crooks, he stated, “the whole treaty is but one series of iniquity & wrong and the half breeds here are so exasperated they will not move a step with the Indians, but will go by themselves. This is the boasted paternal regard for the poor Indians, ‘O shame, where is thy blush!’” He noted that part of Article 3, which provided a parcel of land for Taliaferro’s interpreter Scott Campbell, had been kept secret. “Not one of our number knew of this provision till the Indians were called upon to sign it after it was read to them.” In the end, the grant to Campbell was stricken from the treaty by Congress.65

In fact, Sibley’s own behavior exemplified the difficulties of getting a fair treaty for the Dakota. Sibley supported the American effort to secure the Dakota land through a cession in the hope that he might then have the Dakota accounts on his trader company books satisfied. On the other hand, Sibley claimed he was concerned about providing for the material well-being of the Dakota, many of whom trusted him and some of whom were related to him through their extended kinship system, based on his relationship with a Dakota woman. By expressing his concern and by actually taking some actions that addressed benefits to the Dakota, Sibley was able to maintain his influence with them and encourage their acquiescence to the cession in the treaty—which of course would secure his own material well-being.

While it is arguably the case that Sibley’s efforts had a beneficial effect on the Dakota in terms of their ability to maintain and provide for a decent way of life, the documentary evidence makes clear that his central concern throughout was to maintain his own financial security and also to secure his position in the growing immigrant-settler community. In a letter written to Ramsay Crooks after the treaty was signed, Sibley demonstrated that neither he nor the other traders would be satisfied with what they got out of the treaty for the land east of the Mississippi. He wrote, “The Sioux Indians leave today for home, having come to the conclusion not to treat for the land West of the Miss[issippi], which I am not sorry for, as we can make much better treaties at home than we can here.” He was already thinking of the next treaty.66

After the treaty signing, Dakota leaders met with Sac and Fox to negotiate for peace and then returned to the Upper Mississippi. Nearly nine months elapsed between the Dakota treaty signing and its formal proclamation, with an additional delay before the promised annuities would begin arriving at the agency. This period was filled with anxiety, fueled in part because even before the treaty was proclaimed white lumbermen, loggers, and settlers had begun to come into the region. Two years after the treaties were signed, the first sawmill on the St. Croix was put in operation at Marine. Five years later, in 1844, lumber manufacture was begun at Stillwater.67

In May 1838 Taliaferro noted that several Dakota chiefs came to the agency to report their dissatisfaction, based on “reports all winter unpleasant to the Indians—& calculated to render them suspicious of the government and dissatisfied with their tr[e]aty—& if practicable with their Agent and Interpreters.” They had been worried “that the treaty would not be fulfilled—that their people thought they would be deceived—with many other idle Stories.” He noted, “It is a hard matter for the Agent to disabuse their Ears as to much ridiculous stuff Infused into their minds.” Taliaferro tried to quell the rumors they heard, though his task was considerably difficult in the case of the islands, as they had been included in the land cession contrary to Dakota wishes. A few days later Taliaferro wrote that he told visiting chiefs “to say nothing about Islands which had been sold nor the land—but leave the whites alone and not seek to disturb Set[t]lers nor to make war on the Chippewas on the Lands which they had sold to the United States.”68

Some of the annuity goods and money began to be paid in the fall of 1838. However, in the years ahead, the first provision in Article 2 proved to be a more lasting problem. Under the treaty, the U.S. government would “invest the sum of $300,000 (three hundred thousand dollars) in such safe and profitable State stocks as the President may direct, and to pay to the chiefs and braves as aforesaid, annually, forever, an income of not less than five per cent. thereon; a portion of said interest, not exceeding one third, to be applied in such manner as the President may direct, and the residue to be paid in specie, or in such other manner, and for such objects, as the proper authorities of the tribe may designate.” Strictly interpreted this clause would have provided the Dakota, apart from any other treaty arrangements, with an annual payment of ten thousand dollars in perpetuity to be divided up by the tribal leadership. Another five thousand dollars would be applied for whatever the president decided. Government officials appear to have assumed the government would spend this money for educational programs, including the missionary schools. Paying this money directly to the Dakota was opposed by missionaries, who felt it would “render them indolent and dissipated,” though their point of view was hardly disinterested.69

There had been no real discussion of schools in the treaty negotiations. On the second day, Commissioner Harris had noted that with the money received from selling the lands the Dakota could “buy a great many comforts” and could use it to “build churches, to establish schools, to procure blacksmiths.” When the first part of Article 2 was initially presented to the Dakota, Harris stated that the interest on the principal, which was then $200,000, “would be sufficient to maintain schools support Blacksmiths and all the necessary articles if given them at once it would be soon lost.” At the same time, this first draft of the treaty contained $170,000 for “agricultural purposes, smiths, etc.” Throughout the process the Dakota had never mentioned schools. The closest they came to the subject was when Kaḣboka (Koc Mo Ko, the Drifter), the chief from the Black Dog village and later Cloud Man’s village, asked for help in teaching them how to plant corn and “cultivate our fields.”70

Even the ratified treaty did not refer to schools, but it contained in the fifth provision of Article 2 a promise “to expend annually for twenty years, for the benefit of Sioux Indians, parties to this treaty, the sum of $8,250 (eight thousand two hundred and fifty dollars) in the purchase of medicines, agricultural implements and stock, and for the support of a physician, farmers, and blacksmiths, and for other beneficial objects.”

The official government journal kept during the 1837 treaty negotiation makes clear the divergence between the recorded statements and conversations of government officials and Indian people and the resulting wording in the treaty. Despite the Dakota’s specific requests, language appeared in the treaty that did not follow their wishes. As a result, misunderstandings increased in the years that followed. In particular, Dakota people were not content to have the decision about the school fund left entirely in the hands of government officials. For several years the money was not spent at all, accumulating to the amount of fifty thousand dollars in 1850. This fact would be a bone of contention leading up to the treaty negotiations in 1851.71

The misunderstandings that arose both during the negotiations for the Treaty of 1837 and later during its implementation illustrate a number of misconceptions over the terms of the treaty itself that reflect a deeper cultural divergence in the relationship the two peoples at the treaty table had with the land. The Americans assumed the Dakota would be operating out of the American narrative, with its distinctive view of land as subject to possession and therefore sale. The Dakota at this time, however, are unlikely to have embraced this view—or even to have fully comprehended it. They would have had to change the entire self-understanding of their identity and the land in which they lived. The historical record does not support such a conclusion.

THE TREATIES OF TRAVERSE DES SIOUX AND MENDOTA, 1851