CHAPTER FIVE

Reclaiming Minnesota—Mni Sota Makoce

“By putting forth our stories we are exerting this belief in ourselves, in our history, and our ability to transform the world.”

Waziyatawiŋ Angela Wilson, Remember This! Dakota Decolonization and the Eli Taylor Narratives

The treaties of 1851 marked the beginning of the Dakota’s exile from their homelands in Minnesota. The Dakota people were not given a permanent home in which to live, and efforts to confine them to the region of the Upper Minnesota River began before the treaties were even ratified. Willis A. Gorman, who succeeded Alexander Ramsey as governor of Wisconsin Territory in May 1853, took official charge of the removal beginning in August of that year. Although the Dakota did not have full possession of their reservation and preparations to receive them at their new locations were far from complete, Gorman persuaded the Red Wing and Wabasha bands to move as far as Kap’oża in September. By November he had succeeded in getting all but a few of the Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ, Sisituŋwaŋ, and Waḣpetuŋwaŋ who lived on the Mississippi and lower Minnesota rivers to move to the Upper Minnesota. Gorman noted, however, that “A portion of Wabasha’s band left the Village near Lake Pippin [sic] on the Mississippi R and hid themselves in the country on the Red Cedar river near the Iowa line. But every soul of every other have been removed.” An agency was established on the south side of the Minnesota River near the mouth of the Redwood, about fifteen miles above Fort Ridgely, the new military post.1

During the removal process, Gorman recognized the difficulty of defining a reservation consisting of ceded land in which the Dakota resided under the sufferance of the president. Writing to the commissioner of Indian affairs, he stated that there were places in the ceded lands the Dakota were leaving that were “quite as much out of the reach of the white settlements as on the purchased reservations,” which were actually, by the original terms of the treaty, reserved from the lands ceded. If the reservation was to be open “to all to come and go at pleasure,” then there was no way to protect Indian occupancy through the laws generally applied to “Indian country.” Gorman declined to authorize extensive improvements on the reservation lands until the matter could be settled. Despite these difficulties, he was determined to keep the Dakota on the reservation.2

Plowing and the construction of a few houses for the Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ and Waḣpekuṭe bands began in 1854. But supplies and food were lacking, due in part to government appropriations that did not fulfill the 1851 treaty provisions and to continual delays in the delivery of annuities. To support themselves, many Dakota continued to return throughout the 1850s to areas in which they had lived, hunted, and harvested for generations. In January 1855, Gorman allowed Dakota to hunt deer along Rice Creek and at Rice Lake. The St. Paul Daily Democrat reported on January 27, 1855, that they had “killed five hundred deer, in addition to a large amount of smaller game.” A well-known daguerreotype of tepees adjacent to the John H. Stevens house, in the area of present-day downtown Minneapolis, was probably taken during one of the removed Dakota’s return visits. Meanwhile Sisituŋwaŋ and Waḣpetuŋwaŋ bands located farther up the Minnesota River had received very little assistance on their reservation. They continued hunting as a primary form of subsistence during the winter.3

Even before ratification of the 1851 treaties and removal of the Dakota from the ceded lands, whites predicted the Dakota would disappear from the landscapes in which they had lived for thousands of years. And, at this point, the Dakota began to disappear from the written history of Minnesota. In February 1853, just before the treaties were proclaimed by the president, Governor Alexander Ramsey, acting as president of the Minnesota Historical Society (which was founded in 1849, within the first months of the territory’s existence) wrote a letter, with the historian Edward D. Neill, to the commissioner of Indian affairs in Washington: “The Dakota Indians having ceded their territory on the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, in a short time the villages of this tribe which greet the eye of the traveler from Galena to Fort Snelling will be obliterated.”

Ramsey and Neill noted that ever since the territory’s organization, white inhabitants had had “the most friendly relations with this nation.” They had seen Dakota in the streets of St. Paul and had looked at them as their “new neighbors.” They had taken “lively interest in their customs and culture.” At the fourth anniversary of the Minnesota Historical Society, held in St. Paul, the organization passed a resolution requesting that a member of the society edit a work on “the early history, customs, and belief of the Dakotas, as a memorial of the people who now dwell where our children will build and plant.” They also resolved to ask for the right to use some of the plates prepared for the massive six-volume work on Native American tribes compiled by the former Indian agent Henry Schoolcraft and published at government expense beginning in 1851. That work included the engravings based on the works of Seth Eastman, the military artist and officer stationed at Fort Snelling in the 1830s and 1840s.4

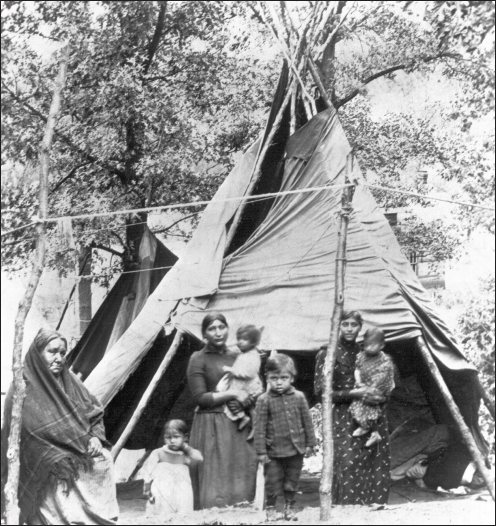

Tepees of Dakota people camped in what would one day be the intersection of Hennepin and Nicollet avenues in downtown Minneapolis, shown in a daguerreotype taken in the 1850s. A portion of the house of city pioneer John H. Stevens is visible in the background. Because of poor food supplies on the reservations created under the Treaty of 1851, Dakota people continued to return to the areas they had ceded, including the Twin Cities.

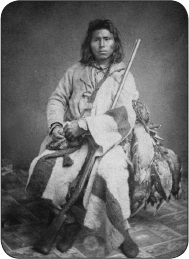

A Dakota hunter was probably photographed in a St. Paul studio in the 1850s; he may have come to sell his ducks to local grocers.

Neill, a Presbyterian minister who was the author of the first histories of Minnesota as a territory and a state, had already begun to gather materials about the Dakota, working with some of the missionaries who had arrived in the region in the 1830s. Though the missionaries’ purpose was to convert Dakota people to Christianity and to change the Dakota way of life, they made a real effort to record the Dakota language and traditions, not just for their own uses but for what they viewed as posterity, though perhaps a posterity that would give them credit for their work. One motivation was the belief that removal of the Dakota from their earlier band locations after the Treaty of 1851 would mean the earlier history of the places they were leaving would be lost.

The bilingual Dakota-English publication Dakota Tawaxitku Kin or The Dakota Friend, published by Samuel and Gideon Pond in 1851 and 1852, included a series of articles on the history of the Dakota, gleaned not only from French sources but also from the Dakota language and oral tradition. An issue published in March 1851 included a short article, “Dakota’s First History,” containing a description of the earliest French commentators on the Dakota. This was just the sort of account one would have expected non-Dakota to view as authoritative. But the same issue contained another article about “hints concerning the traditionary history of the Dakotas.”

The author of this and subsequent articles based on Dakota oral tradition, who may have been Gideon Pond, began by suggesting that he had little confidence in Dakota oral tradition, a view the Dakota themselves would not have shared. He gave the opinion that the Dakota did not see any importance in their own history, writing that “a book on this subject is lost in the death of every old man.” It was left, he said, for “white men, half-breeds, and educated Indians” to “collect and preserve” Dakota traditions. The author appeared to hope that a person of mixed ancestry, who knew how to read and write, someone like the Ojibwe historian William Warren, would appear among the Dakota. He concluded the first installment by stating, “Is it not the imperative duty of every Dakota, or half-breed Dakota, who can read and write—a duty which he owes to himself, his people, and the world—to commence, without delay, to glean in earnest in this long neglected field, formerly rich in Dakota tradition.”5

In May 1851 the journal included the first of several of these articles based on oral tradition. The author stated that he wanted to contribute his “mite of Dakota history” in the hopes that it would provoke others to contribute in a similar fashion on the Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ Dakota and other groups: “Who will give us the Sisitonwan, Warpetonwan, Ihanktonwan and Titonwan traditions? Who will collect and write out their interesting history, as it has been handed down by themselves?”6

In subsequent issues, further articles drew together information from the Dakota oral tradition and from early European sources while also including important accounts of Dakota stories and traditional beliefs such as the Wakaŋ Wac̣ip̣i or medicine ceremony. Another focus was language, particularly the way in which the names of Dakota bands and villages preserved a piece of their history, a record of where and how they lived in the past. The interest in language was shared by another missionary, Stephen R. Riggs, who wrote in the 1893 version of his Dakota Grammar, first published in 1852, that the Dakota people carried with them “to some extent, the history of their removals in the names of the several bands,” a point supported by the names recorded by Pierre Le Sueur 150 years before. Dakota names for particular communities recorded where the Dakota had been and where they moved at different points in their history. Village and group names were a link between the written record and the oral tradition.7

Though influenced by missionary attitudes and language, these accounts offered a Dakota view of history not as an abstraction but within the context of the world view and values of the people themselves. The Dakota Friend’s perspective on the Dakota tradition was more sophisticated than that of other non-Dakota observers, but it did show many biases, in particular in its sense of the precariousness of Dakota knowledge about their ancient homelands, a belief that oral tradition would not be able to survive. If there was any faint truth in these predictions, they might seem eerily prescient when viewed with the knowledge that scarcely ten years from the date of the articles almost all of the Dakota in Minnesota would be driven from their homelands. The precariousness of oral tradition would be an effect of genocide practiced against the Dakota, tearing the people from the places in which that tradition was encoded.

EXILE AND RETURN

As a result of the Dakota–U.S. War of August and September 1862, there was widespread hatred for the Dakota among whites in Minnesota. All Dakota regardless of their actions were punished. Many became refugees on the prairies to the west and in Canada, the object of military actions by the U.S. Army. Thirty-eight Dakota men were hanged at Mankato in December 1862 and more than 260 others, who had been sentenced to hang but whose sentences were commuted by President Abraham Lincoln, were sent to a prison in Fort Davenport, Iowa, for varying terms. Approximately seventeen hundred Dakota men, women, and children were placed in a concentration camp below Fort Snelling during the winter of 1862, where many died. In May 1863 as many as 1,310 surviving Dakota left Fort Snelling in two steamboats for a site at Crow Creek, near Fort Randall on the Missouri River, Dakota Territory. As historian Roy Meyer put it, never again would the Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ, Waḣpekute, Sisituŋwaŋ, and Waḣpetuŋwaŋ Dakota occupy a “single fairly well defined land area.” Instead, wrote missionary John P. Williamson, “henceforth they were scattered over states and provinces, with hundreds of miles separating their dispersed settlements and the lands rapidly filling up with white men, who learned eventually to tolerate the Indian, if only to exploit him, but never to accept him as an equal.”8

A young Dakota girl holding her doll, shown here in a photo from the 1880s or later, was one of the members of the community who survived in Mendota long after the exile of their relatives from the state in 1863.

After 1862 a few hundred Dakota people remained in Minnesota, some providing assistance as scouts and soldiers in the battles against their fellow Dakota. Some were able to take refuge in Mendota under the protection of Henry Sibley, who at the same time was out on the plains seeking to punish their relatives who had never been captured. Others were protected in Faribault under Alexander Faribault and Bishop Henry Whipple. Some continued to make use of their traditional resources.

Little was done by the federal government to provide for the Dakota who remained in or those who had returned to Minnesota—until the 1880s, when federal appropriations allowed for the purchase of small parcels of land at Hastings, Birch Coulee (near the old Lower Agency), Prior Lake, and Prairie Island. Purchased land was first given in title to individuals and later only to those who had lived in Minnesota before the arbitrary date of May 20, 1886, and who wished to cultivate the land. A January 1889 census of the “Mdewakanton Sioux in Minnesota,” compiled by the Birch Coulee agent Robert Henton, enumerated 264 people in eighty family groups, including settlements at Redwood, Prairie Island, Hastings, Bloomington, Prior Lake, and Wabasha and camps at Grey Cloud Island and Mendota. This figure did not include all Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ Dakota in Minnesota but rather those living in Dakota communities and considered most in need. A census taken ten years later by U.S. Indian inspector James McLaughlin recorded 903 Dakota people, including those residing in Indian communities as well as many living in white cities and towns.9

After 1900 many Dakota continued to live in locations covered by these land purchases, where they were permitted “land assignments” on territory that continued to be held by the federal government. Individual Dakota were not permitted to own this land. Many other Dakota bought their own land or lived in white communities. In the 1930s, under the Indian Reorganization Act, communities were organized under tribal constitutions at Lower Sioux and Prairie Island, while an informal organization was created at Upper Sioux where Sisituŋwaŋ and Waḣpetuŋwaŋ had begun to return in the 1880s. In 1969, the Shakopee community was organized around land purchases at Prior Lake. Despite efforts from members of Lower Sioux and Prairie Island to organize as Mdewakanton Sioux of Minnesota, the federal government insisted arbitrarily on organization based on previous federal land purchases.10

RECLAIMING THE LAND THROUGH STORY

Despite the missionaries’ fears about the precariousness of Dakota oral tradition, Dakota people themselves kept the traditional knowledge about Mni Sota Makoce alive. Some Dakota also began to write down stories as a way of preserving them and of spreading the knowledge of Minnesota as a Dakota place. Many of these Dakota writers recounted or translated traditional stories about the origins of the Dakota people and their ties to specific places in the landscape. Frequently published in the past as children’s stories or folktales, they serve as a record of culture and history as well as of land tenure, reclaiming in language the land the Dakota were forced to leave. Julia A. LaFramboise and Charles A. Eastman are two of the earliest published Dakota writers born before exile.

Julia A. LaFramboise is often referred to as the first Dakota woman “to translate and record Dakota legends”; her stories appeared in English in Iapi Oaye, the Dakota- and English-language newspaper established by Stephen R. Riggs and John P. Williamson in 1871. Her translations of seven Dakota stories include “The Orphan Boy,” which describes a large Dakota village along the “sea shore” of Lake Superior, and a version of “Hogan wanke kin—The Place Where the Fish Lies,” about the sandbar on the St. Croix River.11

LaFramboise was born in 1842 into distinguished and influential native families. Her mother was Hapstiŋna (also known as Julia), the third daughter of Iṡtaḣba or Sleepy Eye. Her father was Joseph LaFramboise II, son of the Odawa trader Magdelaine Marcot and her French husband Joseph LaFramboise I. Julia LaFramboise’s early education came from missionaries Stephen R. Riggs and Amos Huggins, and she was later sent to the Western Female Seminary in Ohio. She returned to Minnesota in 1860, where she was appointed as a teacher at Lac qui Parle by the Indian agent. A member of the Hazelwood Republic, established by Stephen R. Riggs for Christian Dakota, she remained at U.S.–controlled Camp Release in the 1862 war to serve as an interpreter for Tataŋka Nażiŋ (Standing Buffalo) and other Dakota leaders who corresponded with Sibley. When the majority of the Dakota were removed from Minnesota in 1863, LaFramboise sold her “Half-Breed Scrip” (based on her claim to land set aside for people of mixed Dakota-European ancestry in the Treaty of 1830) in order to fund her continued education at Rockford Seminary in Illinois. In August 1867 she received a teaching certificate granted by the Hennepin County superintendent of schools and was listed as a Minneapolis Public School teacher. She then went to Santee, Nebraska, in the spring of 1869, where she taught the Dakota people to read and write first in their own language and then in English. She died of tuberculosis in 1871.

Charles Eastman became famous as a Dakota writer whose explicit mission was to reclaim Minnesota as a Dakota place. He did so by situating all his books within the Dakota geography of Minnesota, placing actual events in specific Dakota places. Eastman was born in 1858 among the people of Cloud Man’s village after their removal to the Upper Minnesota River following the Treaty of 1851. His grandparents were artist Seth Eastman and Wakaŋ Inażiŋ Wiŋ (Stands Sacred), Cloud Man’s daughter. Charles Eastman’s Dakota family was exiled to Canada in 1862. They lived along the Saskatchewan River in Saskatchewan and Manitoba until being reunited with Eastman’s uncle and father, who had been in prison at Fort Davenport. Eastman then lived in South Dakota before attending Knox College in Illinois. He received a teaching certificate from the Hennepin County superintendent of schools in October 1866 and went on to receive an undergraduate degree from Dartmouth and a medical degree from Boston College. He was stationed at Pine Ridge Indian Reservation as a government physician during the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890.12

Eastman would later write extensively about the origins of his family in Minnesota. In his book Indian Boyhood, he told of his great-grandfather Cloud Man, “whose original village was on the shores of Lakes Calhoun and Harriet, now in the suburbs of the city of Minneapolis.” He told of the ball game at a Waḣpetuŋwaŋ village on the Minnesota River, when he received his Dakota name, Ohiyesa, meaning the winner (see page 119). In another story Eastman referred to the place where his family went maple sugaring along the Minnesota River, their last Dakota sugar-making before 1862. Other stories about his people’s history in Minnesota were relayed to him during his many childhood visits with Dakota elder and historian Smoky Day. Eastman and LaFramboise represent the impact of oral tradition about Dakota connections to Mni Sota Makoce as a bridge between oral history and printed primary sources.13

Charles Eastman, the great-grandson of Maḣpiya Wic̣aṡṭa or Cloud Man, shown in 1897, became widely known in the early twentieth century for his many writings recording the heritage of the Dakota in Minnesota.

RECLAIMING DAKOTA PLACES IN MINNESOTA

Throughout the 150 years following exile, many Dakota have sought to retain or reclaim the heritage of their homelands, including places which had been part of their history and culture for hundreds of years. A history of Washington County and the St. Croix River region recorded in 1881 that Dakota people continued to make use of the wild rice resources along the Rice Creek corridor in Anoka and adjacent Washington counties. It reported that Rice Lake just east of Hugo “has long been the resort of a band of Indians from Mendota, who go to it every summer, bringing with them from eight to twelve lodges; they gather rice during the summer, which they sell in St. Paul. The lake affords them excellent fishing-ground, containing more pickerel than any other lake in the town. It is fed by springs on the east and west sides in such a quantity as to furnish a steady flow of water into Rice Creek.”14

Exiled Dakota began returning to Minnesota in the 1870s, often going to places where the Dakota who had remained were still living and to places where they had lived before. Dakota anthropologist Ella Deloria wrote about her conversations with Minnesota Dakota: “Dakota felt pulled to the region where their dead were put to rest. A survivor of the 1862 Minnesota Uprising reported in her interview the following: ‘We were driven out of Minnesota wholesale, though the majority of our people were innocent. But we could not stay away so we managed to find our way back, because our makapahas were here.’ The term means earth-hills and is the Santee idiom for graves.”15

Dakota residents of the Mendota area, who lived near the sacred hill of Oheyawahi/Pilot Knob in the 1890s, were recorded by photographer James Methven.

Like many of the burial mounds that covered lakeshores and riverbanks in Minnesota, a large mound at White Bear Lake was “demolished” in April 1889 as a result of a road project. These workmen are cutting trees in preparation for the destruction.

The attraction of burial sites and culturally important places was noted by whites. The Hastings Gazette reported on February 20, 1866, in reference to the Dakota’s return to Oheyawahi, the hill opposite Fort Snelling, “The Pilot Knob is an ancient burial place of the Dakota’s, and is yearly visited by many of the Indians of that nation.” Despite the Dakota people’s knowledge about places of importance to them, reclaiming their connection was difficult because of white Minnesotans’ residual prejudices against them and the growth and development of cities and towns, especially in the Twin Cities area. Even if knowledge of the importance of places as sacred to Dakota people existed, it was seldom seen as a reason to preserve such places.

As areas along the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers were developed from the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth, destruction of burial mounds was a routine activity. Such mounds were mapped extensively by archaeologists during late-nineteenth-century surveys. Many of these mounds have since disappeared. In a booklet called Burial Places of the Aborigines of Kaposia, South St. Paul historian Reinhold Weiner wrote in 1974 of the fate of many burial mounds. Of one mound group located on a bluff above Concord Street, Weiner wrote, “This bluff existed as late as 1885 when excavations began for fill and sand and gravel…This was later known as the Stiefel pit.” Of another mound he wrote, “In the winter of 1973 I tried to locate this mound but they had already started a sanitary land fill in this area.” For a group of eleven mounds, once the “largest recorded burial place in South St. Paul,” he noted their destruction through placement of several sandpits as well as street grading and home building: “This must have been a very impressive sight along the brow of this bluff to see those eleven mounds in a row.”16

Efforts to protect such sites did not begin on a statewide level until the 1960s and 1970s. Archaeologists and Indian people working together helped create laws to protect burial places. But for many more sites, it was already too late.

BLACK DOG VILLAGE AND PROTECTING NATIVE AMERICAN BURIAL SITES

Traditional burial places in Minnesota continued to disappear at the hands of developers well into the twentieth century. After midcentury, however, attempts were made to halt the destruction. In the late nineteenth century a group of 104 mounds had been mapped in the area of Black Dog Village, located on the south side of the Minnesota River in present-day Eagan, then one of the townships of Dakota County. The first recorded excavation of a Black Dog cemetery took place in 1943 when Lloyd Wilford, a University of Minnesota archaeologist, explored a site disturbed by a molding sand pit on Thomas Keneally’s farm in Eagan. Wilford found four historic Dakota burials in rough wooden coffins. Included with the burials were a variety of metal trade artifacts, glass and shell beads, and a pipestone pipe.17

Excavations of other burial sites in the area by the Science Museum of Minnesota in 1963 and by the Minnesota Historical Society in 1968 took place as a result of highway construction. Some of the remains uncovered were later reburied at the Lower Sioux Community. Another burial site at Black Dog was discovered in January 1977 after a report from a concerned citizen. The site was included in the same quarter-section where the first Black Dog burial was excavated in 1943. It was slated to be used as a borrow pit for gravel for the construction of a new Cedar Avenue Bridge. Although the highway itself did not affect burial sites, the contractor on the project proposed using a nearby property for the borrow pit. The digging was expected to impinge directly on the area where Wilford had found remains in 1943.18

In the months that followed, negotiations to save this burial site involved the Minnesota Sioux Inter-Tribal, Inc. (also known as the Sioux InterTribal Council), which represented the Upper Sioux, Lower Sioux, and Prairie Island communities; the Minnesota Indian Affairs Intertribal Board (now the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council); and the Minnesota Historical Society. Dakota representatives were unanimously opposed to any plan to rebury the bodies or further disturb the burial ground. Prior to 1976 there was no specific protection in state law for Indian burial grounds, though there was a rule against destroying tombstones and other features of cemeteries and discharging firearms in such places. This provision was amended in the 1976 legislative session to forbid damage to any “authenticated and identified Indian burial ground.” The law provided that Indian cemeteries must be protected from destruction and that the Indian Affairs Board had to give permission to relocate an Indian burial ground, but it offered little instruction on how to “authenticate” and “identify” Indian burial grounds or what specifically could be done to save them from destruction. It was unclear how the various provisions might be applied to burial grounds on private property. There was also no funding mechanism for dealing with remains on private property.19

In the case of the Black Dog site in 1977, it did not appear practical to allow the remains to lie undisturbed. The landowner was obstinate in his desire to sell off the fill from his property. Even if the segment of land containing the remains was left untouched, it would be in a precarious position because of all the earth removed around it. And there was no funding available from the federal or state governments to acquire the land in order to protect the remains. The Minnesota Indian Affairs Council came to the conclusion that “the most feasible means of insuring the integrity of any remaining burials would involve the removal and reburial of the remaining burials in a secure location.”20

The work of removal was delayed due to the continuing problem of finding the money to pay for the removal. Because of the time constraints, the excavation was primarily a salvage operation, not a scholarly one like Wilford’s in 1943. Over a three-day period twelve archaeologists carefully removed remains and burial materials. After being inventoried the remains were reburied at Morton, on land belonging to the Lower Sioux Community.21

There were many lessons to learn from the events that unfolded at Black Dog in 1977. For Dakota people and native people of other tribes, the experience illustrated the need to strengthen laws to give them more control over what happened to American Indian cemeteries. In October 1977 Don Gurnoe, executive director of the Indian Affairs Intertribal Board, summarized the need to change the law, citing “inequities in current law making it legally impossible to protect Indian burials existing on private lands.” The law made the authentication of a burial ground contingent on a request by a political subdivision owning the land. In the case of Black Dog, Gurnoe later wrote, “the only person having title to the land was the unsympathetic [private] landowner.” If burials were discovered on private land there was no allocation of money or any procedures to be followed under the law.22

As a result of these problems there was a push to change the law. Veteran archaeologist Alan Woolworth, then with the Minnesota Historical Society, worked with Don Gurnoe on a bill submitted at the legislature in 1978 that was passed in early 1980 as Section 307.08 of Minnesota Statutes. Gurnoe noted that the new law looks at the problem of unmarked burials as “an issue of human dignity and treats it cross-culturally.” More responsibility was given to the Minnesota Historical Society and the Indian Affairs Intertribal Board. The bill allocated fifteen thousand dollars for the costs of identification, posting, removal, and reburial of remains. One significant change was an amendment giving the Indian affairs board the power to approve any request to relocate authenticated and identified Indian burial grounds. This new provision stated that “if large Indian burial grounds are involved, efforts shall be made by the state to purchase and protect them instead of removing them to another location.”23

Section 307.08 of Minnesota Statutes still bears the marks of the extensive changes made in the law in 1980. Despite these updates, however, protecting burial sites on private property continues to be a persistent challenge, with no easy solutions.

PROTECTING DAKOTA SACRED SITES

One major challenge for Dakota people today is that despite being able to live within their ancient homelands, they own little of the land and can seldom control what happens to their sacred sites. Even in the case of public lands they often have little influence over the results of decision-making. Perhaps the most contentious issues have occurred within the area known as Bdote, surrounding the mouth of the Minnesota River, the site of some Dakota creation stories and also, coincidentally, within the Fort Snelling military reservation negotiated in Pike’s treaty of 1805.

Many areas within Bdote were preserved because of their natural features and their connections to European American history, but until recent years the importance of these places for Dakota people had been little noted. Minnehaha Falls, several miles north of Fort Snelling, was preserved beginning in the 1880s because of its association with the inauthentic Indian legends popularized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in The Song of Hiawatha. Later the homes of Henry H. Sibley and Jean-Baptiste Faribault in Mendota opposite the fort were preserved through the efforts of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Fort Snelling State Park, including within its boundaries the site of Pike’s treaty signing and, unheralded, the concentration camp of 1862–63, came into being in 1962. In the 1950s the remains of Historic Fort Snelling, the original fort built in the 1820s, were saved from highway construction and the Minnesota Historical Society began to reconstruct the fort as it existed in the 1820s. In none of these efforts was the importance of these places to the Dakota a major focus.24

In the 1990s, the proposed expansion and reconstruction of Highway 55 from downtown Minneapolis to the Mendota Bridge led to controversy because of its effect on Minnehaha Park and the area to the south around Mni Sni, Coldwater Spring. A coalition of environmentalists and native people fought this construction through protests and by occupying houses, groves of trees, and lands in the highway’s path.25

Among those opposing the highway was a group known as the Mendota Mdewakanton Dakota community, descendants of Dakota people who intermarried with French Canadian employees of Henry Sibley, including the family of trader Jean-Baptiste Faribault and Hypolite Dupuis, Sibley’s bookkeeper. Dupuis was married to Angelique Renville, a cousin of Little Crow, the leader of the Kap’oża band. These families, not among those exiled in 1862–63, continued their association with the area of Mendota throughout the late 1800s and into the twentieth century.26

Though they were relatives of Dakota who were members of the federally recognized Dakota communities in Minnesota, the Mendota Dakota were not a federally recognized community. However, their leader, Bob Brown, and other community members felt an obligation to defend sites of importance to Dakota people. Coldwater Spring and other sites in the area were directly endangered because of the effect construction would have on the water and on the landscape around the spring, which was located on property once operated by the Bureau of Mines–Twin Cities Campus, just east of the path of Highway 55.27

Making the case for the importance of the spring and the area known as Bdote to the Minnesota Department of Transportation and to the Federal Highway Administration proved problematic. In retrospect it is clear that government administrators’ skepticism about the area’s cultural importance was not just about the people—a non-federally recognized group of Dakota—bringing the message. It was also about the message itself, that there were now Dakota people making their voices heard in the Fort Snelling area and in larger Minnesota, seeking to reclaim their homelands and be involved in decisions about places of cultural importance to them.

Subsequently a cultural resource firm was hired by the Minnesota Department of Transportation to examine some of the issues associated with the highway construction. While the study found no evidence that the highway would impinge on historical resources, including an arrangement of four oak trees said by some to be culturally important to the Dakota, it compiled evidence that Coldwater Spring could very well be a Traditional Cultural Property, or TCP, under the criteria of the National Register of Historic Places. Designation as a place of traditional cultural importance is one way to protect sites from damage during projects paid for with federal money. The study recommended a full TCP evaluation, including consultation with Dakota and other Indian people to examine the question. Referring to places of cultural importance as TCPs was one of several ways tribal groups could seek to have an effect on government actions. Sacred sites were also specifically mentioned in President Bill Clinton’s Executive Order No. 13007 of May 24, 1996, relating to Indian sacred sites. However, the order merely required government agencies to accommodate tribes in using the sites and did not offer any real protection for them.28

Despite the efforts of highway opponents, Highway 55 was built, although because of a state law its design had to be altered to minimize the impact on the flow of water to Coldwater Spring. In the years that followed the Highway 55 controversy, action was taken on other fronts in the area of Bdote. In 2003, as a result of plans for a 157-unit housing development on Pilot Knob, the hill was nominated to the National Register as a TCP and a place of importance because of its association with the signing of the Treaty of 1851. In 2004 the Keeper of the National Register agreed that the site was eligible, though it could not be listed because of the landowners’ objections. In the following years this private land was purchased through a variety of funding agencies and preserved as open space by the City of Mendota Heights, precluding any development.29

One of the difficulties in protecting Oheyawahi/Pilot Knob and other Dakota sacred sites has to do with the concept under National Register criteria of “integrity,” meaning the degree to which a site preserves the characteristics that make it important. The question of integrity is easier to answer about buildings or archaeological sites than it is about natural sites. Darlene St. Clair, an educator and Lower Sioux community member, noted that in some cases Dakota traditional cultural sites bear the litter of settlement, industrialization, and commercialization of the landscape, including industrial structures and government buildings. Pilot Knob is surrounded by freeways, the Wakaŋ Tipi/Carver’s Cave site is on the edge of a railroad yard, and the Coldwater Spring site is filled with crumbling buildings. The question of whether such sites can still be sacred for Dakota people is often raised. But as St. Clair noted, to assume these sites have to be naturally beautiful to be TCPs is to mistake beauty for sacredness. These sites may once have been beautiful and it might be good to protect them from further changes. But even if they lose the natural beauty they once had, their sacredness is not destroyed.30

In October 2009 Lakota Chief Arvol Looking Horse participated in a pipe ceremony on Pilot Knob to celebrate the protection of the land on the hill from development, noting that sacred sites are for Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota peoples “power points, the grid” through which people interact with the landscape. From this point of view development, while damaging to the environmental characteristics of sacred places, sometimes reflects the energy and power found there. Chris Leith, the late spiritual leader of the Prairie Island Dakota, also present at the 2009 event, stated in a 2003 interview that Bdote, a site of creation for the Dakota that contains many sacred sites, was a “vortex” in the landscape. The very presence of Fort Snelling, the airport, and the complex freeway system there reflected the site’s powerful energy. Leith cautioned, however, that powerful spiritual places should rightly be left alone, not because they would be damaged by what was built upon them but because in the long run the nature of the place would damage what was built there.31

Coldwater Spring, like many sites sacred to the Dakota, survived despite the debris of industrial building such as structures south of the basin where the water from the spring is collected. Since this photo was taken in 2011, the National Park Service has removed the buildings and is undertaking re-vegetation of the property.

Such perspectives are often far from the minds of government agents who make decisions about Dakota sacred sites. In 2005 plans were under way to dispose of the Bureau of Mines site that included Coldwater Spring. As part of an environmental review process, the National Park Service (NPS) hired a cultural resource firm to examine the cultural importance of Coldwater Spring for Dakota and other native groups. Through research and interviews, the firm determined that Coldwater Spring was a TCP for the Dakota people. The report cited the spring “as being significant at a statewide level as a TCP associated with the Dakota communities in Minnesota,” involved in Dakota traditional practices and “important for the continued maintenance of their cultural identity.” The report also noted, in relation to the traditional cultural property’s boundaries, “There is a consensus that the boundaries of Coldwater Spring include not only where the water flows from the rock wall, but also the source of the spring and the location where the spring water finally deposits into the Mississippi River.”32

The study’s findings were based not just on historical facts about the spring itself but on the fact that springs like this one—its water used in the ini ceremony, also called inipi, or “they sweat”—have been known for many years to be of great significance for Dakota people in Minnesota. In addition, Coldwater Spring was located within not only Bdote but also Ṭaḳu Wakaŋ Tip̣i, the place where the water spirit Uŋkteḣi was said to reside. The precarious written record left by whites that the spring was important to Dakota people was not necessary to prove its significance. The traditional accounts given today and the historical records of the importance of springs were enough to show that this spring was a TCP for Dakota people.33

Despite this report and the earlier testimony of Dakota people, NPS staff announced publicly in August 2006 that they would not accept the study’s findings about Coldwater Spring. By that point the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area superintendent had already written to Dakota communities, stating, “After thoroughly reviewing the evidence provided in the report the National Park Service has concluded that neither the Center nor Coldwater Spring meet the specific criteria in the National Register to designate the area as a TCP.” The letter concluded by acknowledging that the spring had “significant contemporary cultural importance to many Indian people” and noting that “the spring is already a contributing element to the Fort Snelling National Historic Landmark and the Fort Snelling National Register of Historic Places District.” In recognition of the “contemporary cultural importance” of the site to the Dakota and the significance of the site in Fort Snelling history, protections would be recommended.34

The condescending words suggested that although the federal government rejected the Dakota communities’ claim to the spring as a historical and cultural feature and in the process rejected the history and cultural traditions on which the claim was based, the park service would try to protect the spring because it was part of a site important for, among other things, its role in colonizing Minnesota and sending the Dakota into exile in 1863. The area’s place in Dakota history was not significant; its white history was. A reaction to these offensive comments could be seen in the support among some Dakota people for a movement to tear down Historic Fort Snelling, where interpretation of military history was often the emphasis to the exclusion of its role for the Dakota.35

The idea that the spring’s cultural and historical importance had to be verified using written historical sources is a problem all too familiar to the Dakota, who in trying to reclaim their homelands are often required to prove, through written sources recorded by white people, the cultural importance of every bit of ground in Minnesota, one square inch at a time.

In fact, the very idea of Traditional Cultural Property was intended in part to avoid requiring written historical evidence produced by non-native people to nominate sites to the National Register. Thomas F. King, who together with Patricia Parker wrote Bulletin 38 of the National Register, which pioneered the concept of the TCP, has written that a people’s belief in the sacredness of particular kinds of places within their homeland makes those places important traditionally regardless of the historical record associated with them: “Traditional cultural properties must be respected for their own sakes—regardless of whether they are referred to specifically in oral history.” He argues that “traditional cultural properties can legitimately be identified through field inspection by knowledgeable people in the absence of specific association with known traditions, and that whole classes of properties—such as ancestral archeological sites—can be categorically identified as traditional cultural properties.”36

The criteria of the National Register as interpreted in Bulletin 38 states that a traditional cultural place is eligible for the National Register “because of its association with cultural practices or beliefs of a living community that (a) are rooted in that community’s history, and (b) are important in maintaining the continuing cultural identity of the community.” King wrote, “if a community traditionally believes that rocks pointed toward the sky are places of communication between this world and the spirit world, and if belief in communication between these worlds is important in maintaining the community’s identity, the fact that its members may not know of any pointed rocks in a given area doesn’t make such rocks, when discovered in the area, any less recognizable to the community’s elders as places of interworld communication, which automatically have cultural significance.”37

In the case of Coldwater Spring, direct oral tradition is related to the spring, but federal officials declared this to be inadequate. One official lamented the lack of more detailed narratives which would support the spring’s significance. Anthropologist John Norder provided an answer to such demands. Norder, whose family is from Spirit Lake, North Dakota, and who has worked in a number of native communities in the Great Lakes region, argued the lack of relevance about the need to prove native connections to particular places—in this case rock art in the border lakes region of northern Minnesota and Ontario—through stories or detailed explanations of their origin and meaning. Landscape itself is perceived by many groups as having its own agency and power with which people today engage, regardless of a relationship proved through narrative. Even if they do not know the “full story” about places of importance, they understand them and know how to act toward them when they see them. In other words, the traditional importance of such places is recorded in behavior, not narrative. Norder noted, “the landscape provides the impetus for stories as much as humans do. Places in the landscape speak, and it is the responsibility of the people inhabiting it to listen and to learn what they must to engage appropriately with it.”38

Norder’s analysis recalls the words of elder Chris Leith, who, during the contentious process which led to the preservation of Oheyawahi/Pilot Knob, was asked repeatedly for a more detailed explanation about the meaning of the hill for Dakota people. Leith stated that the origins of Oheyawahi’s sacred character could not be explained by any person: “There are many questions that no human being can answer.” When Leith was pressed for details about the connection of the site to Uŋkteḣi, he stated,

I just answered it…You asked me something in a different way…That’s a European concept. If they don’t get an answer, well then they’ll ask another way. They can’t accept what they’ve been told. They want to change it…Our ceremonies come in dreams and visions. Our way of life is conducted under dreams and visions. We don’t change it. We don’t have that right. It is not of our making.39

According to the cultural-resources study that found Coldwater Spring to be a traditional cultural place, the meaning of Coldwater Spring can only be understood within the Dakota’s beliefs—ceremonial and cultural—about springs of various kinds. Culturally important places are significant for traditional reasons regardless of whether the particular place has the kinds of specific associations that connect Coldwater Spring to Dakota history and identity. In Charles Eastman’s account of his boyhood years in his family’s exile in Manitoba, he was asked by elders, as part of his becoming a man, to sacrifice to the Great Mystery that which was most precious to him—his dog. He and his grandmother took the body of the dog and laid it inside a cave located along the Saskatchewan River. The immense cave was located fifty feet above the river, under a cliff. “A little stream of limpid water trickled down from a spring within the cave. The little watercourse served as a sort of natural staircase for the visitors. A cool, pleasant atmosphere exhaled from the mouth of the cavern. Really it was a shrine of nature and it is not strange that it was so regarded by the tribe.” They laid down the dog’s body, decorated and accompanied by a pipe, within the cave. The boy’s grandmother spoke the offering: “O, Great Mystery, we hear thy voice in the rushing waters below us! We hear thy whisper in the great oaks above! Our spirits are refreshed with thy breath from within this cave. O, hear our prayer! Behold this little boy and bless him! Make him a warrior and a hunter as thou didst make his father and grandfather.”40

Sheldon Peters Wolfchild, a Lower Sioux Indian Community member and activist, commented on this story, noting that Dakota people living so distant from their homelands had found places that echoed the importance of those they had known for centuries. This cave bore great similarities to Wakaŋ Tipi/Carver’s Cave, where early European visitors mentioned that the Dakota yearly brought the bodies of their deceased family members for blessing. In finding such locations even in exile, Dakota people made clear the importance of place and the characteristics that made such places sacred, ultimately defining them as traditional cultural places.41

Another spring, located near Shakopee and called Boiling Springs, was nominated to and placed on the National Register in 2002 as a TCP, based mainly on an early newspaper article and the testimony of Gary Cavender, a Dakota elder whose traditional accounts were called into question by the NPS when he spoke about Coldwater Spring. The water in this spring was unusual in that it boiled up from the bottom of a deep pool. Given this example, Wolfchild pointed out that the Dakota did not view all springs in the same way. The water from this spring was sacred, according to Dakota elders, but, due to its unusual qualities, was not appropriate for use in ceremonies. Instead, the water of springs like Coldwater—which seeped from between the rocks—was preferred for sweat lodges and other ceremonies.42

Despite community members’ testimony, agencies such as the National Park Service continue to ask for written verification of a site’s importance. Dakota historian Waziyatawiŋ, writing in Remember This! noted that verification is a common requirement in white interpretations of oral history and oral tradition, not just in relation to cultural places. She cited Vine Deloria Jr.’s observation that the differences in native and western views include the belief that native people “tend to be excitable, are subjective and not objective, and consequently are unreliable observers” and that all of the evidence their traditions present must be verified. Waziyatawiŋ comments, “This dismissal of Indigenous perspectives is symptomatic of the relationship of the colonizer to the colonized. Colonial domination can be maintained only if the history of the subjugated is denied and that of the colonizer elevated and glorified.”43

Dakota views on these questions are borne out in part by NPS actions in relation to the Coldwater/Bureau of Mines property. In 2005 and later, Dakota communities in Minnesota sought to obtain ownership of the site, citing their cultural connection to the spring and to Ṭaḳu Wakaŋ Tip̣i and Bdote and making reference to the rights retained under Pike’s Treaty of 1805, Article 3, which states, “The United States promise on their part to permit the Sioux to pass, repass, hunt or make other uses of the said districts, as they have formerly done, without any other exception, but those specified in article first.”44

At a contentious meeting in February 2009 at the Minneapolis Veterans Administration Hospital, which is built on a portion of Ṭaḳu Wakaŋ Tip̣i/Morgan’s Mound, various Dakota people spoke out in favor of Dakota ownership and objected to the NPS’s continuing refusal to recognize the importance of the place for the Dakota. In January 2010, at the end of the environmental review process, the National Park Service announced it would retain ownership of the property for itself, to be used as a public park. The park service issued a press release: “The public’s interest in this site throughout this process illustrates the great significance that the Dakota and so many others attach to this special place…We are excited to be the caretakers, and to work with many partners to tell all the stories associated with this place. There are many layers of history associated with this site, from the Dakota to European settlement to 20th century mining technology.” Since the park service had consistently denied any historical or cultural connection of the Dakota to the property, the statement was surprising. Rejecting Dakota traditions and then using them in the agency’s historical interpretation appeared to add insult to injury.45

The example of Coldwater Spring suggests the Dakota have a long way to go in reclaiming their homelands in Minnesota, whether in achieving protection for their sacred places or in the simplest sense of making Minnesotans aware of their history and contributions. Ignorance and skepticism about their place in the region continues to be widespread. In 2012, when recalling the events of 1862, many remember what happened in August and September of that year. But far fewer remember the words of the Dakota leaders who came to see the French official Joseph Marin in 1754, carrying a map and stating, “No one could be unaware that from the mouth of the Wisconsin to Leech Lake, these territories belong to us. On all the points and in the little rivers we have had villages. One can still see the marks of our bones which are still there…These are territories that we hold from no one except the Master of Life who gave them to us. And although we have been at war against all the nations, we never abandoned them.”46

THE POWER OF PLACE

Human beings have recorded their relationships with places in innumerable ways throughout their existence. They have given descriptive names to special features of the landscape, gathered in powerful areas, and marked their experiences on the land. The power of place is undeniable. Many of us have experienced it in different ways during our lifetimes—returning to ancestral homelands or family burial sites, visiting spectacular places of worship or historic battlefields, or standing in awe of remarkable natural beauty. These places tell us stories and provide us with long-lasting memories. It is through stories and experiences that we understand the power of place.

For Dakota people, this place, Mni Sota Makoce, embodies all of those characteristics. It has been described as our “Garden of Eden,” where the first Dakota people—the Wicaŋḣpi Oyate—walked upon the land given to them by the Creator, the Maker of All Things. As such, everything is imbued with an element of wakaŋ, or sacredness. In describing the “great mystery,” Ohiyesa Charles Eastman observed that sacredness is encountered as it is present in the natural landscape. Those encounters are remembered still today through Dakota place names that tell the stories and histories of our interaction with the land—Minnetonka, Chanhassen, Mahtomedi, Wayzata. And what makes a place sacred is collective memories.47

While story and memory form the basis of all our human experience, it is the written record that we have come to rely on as primary evidence of land tenure and possession. However, that “written” proof includes the earliest forms of inscription on rocks and in caves as well as maps drawn on birch bark and wood described by the first European explorers to this region, the French. Their documentation of villages, burial mounds, and names at the beginning of the seventeenth century testify to the importance of this place as the Dakota homeland. In the extended relationships Dakota people developed with the explorers, the French seemed to understand how they valued kinship, not only between human beings but also with the land.

Their relationship with the land was intimate and reverent. The Dakota knew Mni Sota Makoce as an interconnected network for travel and subsistence and followed seasonal rounds of hunting, fishing, gathering, and cultivating. They understood the power of place and gathered together for ceremonies and celebrations, games and feasts, and to bury the dead. As missionaries and traders entered their territories, the Dakota shared their knowledge of the land and its abundant resources. Conflicts were inevitable, but it was inconceivable that Dakota people would ever be separated from the land of their birth.

By 1805 the lines were beginning to be drawn. Not the maps of waterways and centuries-old travel routes, but the demarcation of possession. Mutual hunting and ricing areas shared by the Dakota and Ojibwe were divided in 1835 by the “S & C” line implemented by the U.S. government. Treaty negotiations in 1851 were supplemented by a written Dakota-language version that underscores the differences in understanding about the meaning of land “possession” and the difficulties of translation by a missionary and interpreters. The vast homeland of the Dakota, “from the great forest to the open prairies,” was reduced by 1858 to a ten-mile strip running 140 miles on the south side of the Minnesota River from Lake Traverse to just west of present-day New Ulm. And then exile in 1863.

To “reclaim” Minnesota as a Dakota place is to once again interact with what is sacred and to recall its stories. We believe the land remembers, and as we walk near Minneopa Falls or in Blue Mound State Park or around Lake Calhoun, we are surrounded by those memories held in the land. These stories recount Dakota experiences and help us remember beyond the historical record. The collective voices of the earliest inhabitants, the explorers, the missionaries, and the historians of this place tell us unmistakably that this is Mni Sota Makoce—Land of the Dakota.