Aristotle now turns to the second of the three ‘elements’ he had enumerated at the beginning of IV xiv, the executive (or, as he puts it, the archai, the ‘offices’ or ‘officials’). He raises a large number of issues: (a) What kinds of official are there? (b) Who appoints them? (c) From whom are they appointed? (d) How are they appointed? (e) What is their tenure of office? (f) What are their function and powers? (g) How do the various officials operate in relation to each other? (h) Which officials, modes of appointment, powers and tenure etc. are appropriate for which constitutions?

Aristotle’s long and discursive treatment of these topics is rich in observation and analysis, and two features of the chapter are of special interest: (1) His attempt, in the second paragraph, to isolate just what we mean by ‘official’, as distinct from persons merely ‘in charge’ of something. As can be seen from Newman’s comments and references ad loc. (cf. also III i and Plato, Laws 767a, 768c) the controversy was a live one. Aristotle briefly tries various lines of approach and plumps provisionally for the rather widely drawn criterion that officials deliberate, decide and give orders – the last function being crucial. But after these inconclusive remarks he drops the search for definition as being of academic interest only. (2) His elaborate analysis, towards the end of the chapter, of the ways in which the various features of appointment may be combined. Admittedly, this matter is of practical interest, as particular constitutions find it expedient to combine them in particular ways; yet, as he virtually admits, he carries the mechanical analysis beyond the point where it could serve any useful purpose. One wishes he had devoted less energy to this enterprise and more to the philosophically interesting question, ‘What is an official as distinct from a mere functionary?’

1299a3 Next, we turn to classify the officials. Great variety is also to be found in this element in the constitution: questions arise about their number and the scope of their sovereign powers, about the length of tenure of office of each (it is made six months in some cases, in others less, in others a year, but in yet others longer periods). Should tenure be perpetual, or for a very long term? And if neither of these, then the question arises whether the same persons should hold office repeatedly, or for one period only, being ineligible for a second. Then there is the officials’ appointment – from whom are they to be drawn, by whom appointed, and in what manner? We ought to be able in all these matters to determine how many different ways are possible and then match them up, looking to see what sorts of officials are best for what sorts of constitution.

1299a14 Another question – and even this is not easy to answer – is, which kinds ought to be called ‘officials’? The association which we call the state1 needs a great many people to take charge of various things, so many that we should not designate them all as officials, neither those appointed by lot nor those elected. I am thinking in the first instance of the priests, whose position is quite different from the offices of state. Then there are the heralds and the trainers of choruses,2 and envoys to be sent abroad, all these being appointed by election. Some responsibilities affect the state, and of these some affect all the citizens, for the purposes of a particular activity (e.g. a general, while they are under arms), others a section only (e.g. a controller of women or children). Other responsibilities affect the household;3 for example, they frequently elect persons to measure out corn. There are also ancillary responsibilities which, when resources permit, will be performed by slaves. Roughly speaking, we may say that officials are those empowered to deliberate and make decisions on certain matters and to issue orders; and particularly the last, since this is the essence of rule. All this makes hardly any difference in practice; disputes about the terms have not resulted in any decision. But it is a question which is open to further intellectual investigation.

1299a31 Turning to more difficult questions, we ask what kind of officials, and how many, are essential – essential, that is, if there is to be a state at all; we ask also what kind, while not essential, are yet useful for a sound constitution. Such questions need to be discussed in relation to every constitution, and in particular in relation to small states. For in the large states it is both possible and necessary to assign separate tasks to separate officials, one to each man because the large number of citizens makes it possible for many of them to sit on the committees, so that one man never holds the same office twice, or only after a long interval, and because every job gets done better when it is the responsibility of one official, not of many. In the smaller states, on the other hand, a number of offices have to be concentrated in a few hands (on account of the small population it is not easy for many to hold office, for who will there be to succeed?). However, sometimes the small states require the same officials and laws as the large; but whereas the small need the same persons to serve frequently, in the others this need arises only at long intervals. Thus there is really no reason why a number of different responsibilities should not be assigned together, because they will not hinder each other, and as a way of counteracting lack of manpower it is essential to make committees serve more than one purpose. (A hook will hang a roast as well as a lamp.) If therefore we can say how many officials are essential for any state at all, and how many are not essential but still ought to be there, then knowing all this we shall find it easier to deduce what sorts of offices are fit to be amalgamated into one.

1299b14 Another point not to be overlooked is fittingly mentioned here. What sort of matters ought to be supervised by many boards for different places, and which other sorts by a single official, whose authority is sovereign everywhere? I am thinking of such matters as keeping order in the market. Should there be a separate market-controller in every place, or one for everywhere? Should divisions be made according to the work or according to the persons? Is all regulation of good order a task for one man, or should there be a separate one for women and children? Similar questions arise when we consider offices in relation to constitutions. Does each constitution make some difference, or none, to the type of offices? Thus, are the same offices sovereign in democracy, in oligarchy, in aristocracy, and in monarchy, even though they are filled not from equal nor even similar people, but from different people in different constitutions – in aristocracies from the educated, in oligarchies from the rich, in democracies from the free? Or are there some offices that correspond precisely to the differences in the officials,4 and in some places do the same offices serve best, in others different ones? For it may happen that here an extensive role, there a minor, for the same office its the situation best.

1299b30 There are however offices peculiar to certain situations and not found everywhere, for example that of ‘pre-councillors’. This is not a democratic institution, but the council itself is; for a body of this kind whose responsibility is to deliberate on business beforehand is necessary so that the people shall get through their work. If this council consists of only a few men, it is oligarchical. But pre-councillors must necessarily be few in number; therefore they are always an oligarchical feature. Where both offices exist, there the pre-councillors stand over the members of the council; for the councillor is a democratic institution, whereas the ‘pre-councillor’ is an oligarchic one.

1299b38 The function of even the council may be weakened at the other end also, as in those democracies in which the people itself meets and takes a hand in everything. This is apt to happen wherever members of the assembly are well paid for their attendance, because this gives them time off to come to frequent meetings and decide everything themselves. A controller of children, a controller of women, and officers with sovereign powers to discharge responsibilities similar to these, are an aristocratic feature, not a democratic one (for who could prevent the wives of the poor from going out when they want to?). It is not oligarchic either, for the wives of oligarchs are rich and pampered.

1300a8 So much for the present on these matters; I must next try to describe from the beginning the ways of appointing officials. The alternative ways in which this can be done fall into three definitive groups, the combination and permutation of which will necessarily be found to include all the methods. First we ask who are those who make the appointments, second from among whom do they make them, third in what manner it is done. To each of these three questions there are three different answers: either all citizens appoint or only some do; appointments are made either from all citizens or from some specified persons,5 the qualification for appointment being property-group or birth or virtue or some similar thing (as at Megara, where only those qualified who had been among the returning exiles who had fought together against the people);6 and all this may be either by lot or by election. These coupled alternatives yield further couplings as follows: some appoint to some offices, all appoint to others; some offices are filled from all, others from some; some are filled by lot, others by election.7

1300a22 8For each of these alternatives there is a choice of four methods: all appoint from all by election or all from all by lot; or all appoint from some by election or all from some by lot (and if from all, either by sections, for instance tribe, deme, or brotherhood, and so on through all the citizens, or else from all on every occasion); or partly one way and partly the other.9 Again, if the appointers are only some, not all, the appointments may be made either by election from among all or by lot from among all, or by election from some, or by lot from some, or partly one way and partly the other – I mean partly by election from all, partly by lot, and partly by election from some, partly by lot. This gives twelve methods, apart from the two couplings.

1300a31 Of these modes of appointment, three are democratic – all appoint from all either by lot or by election or both, that is, to some offices by lot, to others by election. But that not all should appoint at one time,10 and either from among all or from some, by lot or election or both, or some officials from all and others from some, either by lot or election or both (that is some by lot, some by election) – that is a characteristic of a polity. When some appoint from all, by lot or election or both (some officers by lot and others by election), that is oligarchical, and the more so when they appoint from both.11 To appoint12 some officials from all, and others from only some, or some by election and others by lot, is characteristic of a polity, but with a bias towards aristocracy. But it is oligarchic when some appoint from some by election, and when some appoint from some by lot (it makes no difference that this is not in fact done), and when some appoint from some by both methods. When only some appoint from among all, and when all elect from some, that is aristocratic.

1300b5 Such then is the number, and classification in relation to the different constitutions, of the methods of appointing officials. Which method is best for what people, and how the appointments should be made, are questions which can only become clear in conjunction with decisions about what offices there are and what powers they have. By ‘power’ of an office I mean such things as sovereign control of revenue and of security; for the power of a general is different in kind from the function of controlling commercial contracts.

Appendix to IV xv

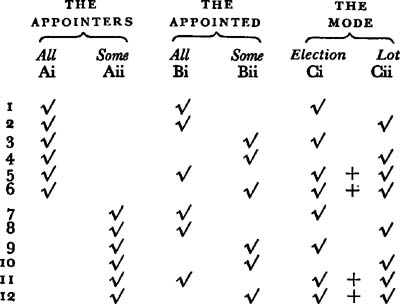

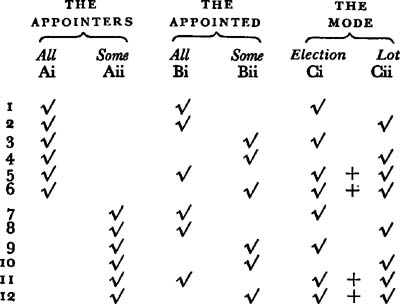

As Rackham remarks in the Loeb translation, 1300a22–b5 is a ‘dizzy passage’ (locus vertiginosus). If I understand it aright, the text down to a31 may be schematized as shown in the diagram. (In 1300a23 I read ‘four’, not ‘six’.)

These are the ‘twelve methods’: 1–4 and 7–10 each describe a method of appointment to all offices; 5–6 and 11–12 each describe a method of appointment coupling election and lot, in the sense that some offices are filled by election, others by lot. (Line 5 is in effect a conflation of 1 and 2, 6 of 3 and 4, and so on.) The ‘two couplings’, which are not represented in the diagram below, are Ai + Aii (all apoint to some offices, some to others), and Bi + Bii (all are appointed to some offices, some to others). Each of the six ‘althernalives’, all couplings apart, has ‘four methods’, represented by the four ticks in each column which have two companions in the same horizontal

‘These (six) alternatives’

(1300a22)

line; e.g. there are four ways of conducting an election by choosing officials from ‘some’ (Bii) of the persons qualified. Hence, the two missing couplings apart, A, B, and C have a total of ‘twelve methods’ (p. 286, middle).

In the second paragraph of the passage, Aristotle isolates which methods are characteristic of which constitutions, and complicates the picture still further by making use of all couplings, Ai + Aii and Bi + Bii as well as Ci + Cii (which is the most frequent): see footnotes for the less obvious instances.