Chapter 1

SIMPLE STOPPERS

The best place to start learning knots is with stopper knots, or knots that are tied at the end of a cord. Stopper knots have many uses and provide an excellent learning base for practicing a wide variety of other knots.

STOPPING AND MORE

Stopper knots, also known as terminal knots or knob knots, are tied at the end of a cord. In its strictest sense, the use of the word knot refers to a stopper knot.

A rope with a knot tied in the end of it is a completely different object than a rope without one. It is easier to hang on to, it cannot be pulled through the same size openings, the end will be less inclined to come unraveled, and it will look different, too. All these changes in the properties of the rope are accomplished with a simple stopper knot.

Basic Usage

To stop a cord’s end from running through a small opening is part of how a stopper knot earns its name. By “stopping” the rope, the knot allows us to suspend something from it. If the cord runs through a lead or pulley, a stopper knot can keep the line from running all the way out, or unreeving. This is commonly done on a sailboat, where the Figure Eight Knot is used for this purpose. It also stops the end of thread from passing through cloth and similar materials in needlework.

A simple stopper knot is often used to make cordage easier to grasp, whether you make it with the string doubled through the end of a zipper, or with larger rope to get a better grip. Several stopper knots can be tied, and spaced out, to give many handholds. When tied in the ends of many cords as if all one cord, it provides a way to keep them gathered.

What’s It Used For?

There are many other uses for stopper knots. They can make the end heavier to use for throwing. Heaving knots are for weighting the end of a rope to assist with throwing the rope. Often a smaller rope is thrown between a boat and the dock, and then used to pull a heavier one over. The same technique is used in many circumstances to get a heavy rope in a hard-to-reach place. In getting a rope over and between two particular branches high in a tree, a rope can be thrown over all of them, and then another can be thrown across it between the branches, from a different angle, 90 degrees if possible. In this manner, the second rope will pull the first down between the two branches. Two common knots for weighting the end of a line are the Heaving Line Knot and the Monkey’s Fist.

Stopper knots can be used as mallets with a soft striking surface, or they can be treated with shellac to harden them. They also use up line to make it shorter. Both the Heaving Line Knot and the Monkey’s Fist have a number of turns that use up line. Depending on how much shorter a cord needs to be, anything can be used from an Overhand Knot to a long Heaving Line Knot or even a coil. They can prevent the end from fraying, although whipping the end, as shown in Appendix A, is a neater solution. Stopper knots are used for decoration, and a knot in the end of a cord can be used as a reminder of something.

MULTISTRAND STOPPER KNOTS

Knot tyers long ago figured out that the strands of three-stranded rope can be unlayed and then tied together to form simple or complex stopper knots. These knots are characterized by simple and easy-to-remember patterns for tying, and their woven appearance. On square-rigged sailing ships these knots were used to stop hands and feet from sliding on ropes. They can also be tied by binding two or more separate cords together. Multistrand knots are also used as a form of decorative knot tying. Some knots, like the Matthew Walker Knot, can serve both decorative and functional purposes.

Multistrand stopper knots can be made in many variations just by using the Wall and Crown Knots (described later in this chapter). They can be combined in various orders and can even be doubled to make a larger knot. To double them, retrace each strand along a previous strand’s path. If a Wall and then a Crown is made, the ends can be tucked down the center from the top and then cut off where they come out the bottom. Then, when someone asks what you did with the ends, you can say that you “threw them away.”

THE OVERHAND SERIES

The Overhand Knot is a distinct knot with its own properties. It is also the basis for both tying and remembering many knots. For instance, the Overhand Knot is the base for two important series of stopper knots, the figure eight series and the multiple overhand series.

OVERHAND KNOT

STEP 1 Pass the running end around the standing part, making a loop, and then pass it through the crossing turn.

STEP 2 Tighten the knot by pulling on both the standing part and the running end.

Besides being the foundation of many different knots, the Overhand Knot has many distinct properties of its own. For example, it weakens most cordage it is tied in by 50 percent or more, and tightening it down can damage the fibers of some ropes. Consequently, it is tied in nylon fishing line to test for brittleness. If fishing line has lost any of its flexibility, it will break very easily as you tie an Overhand Knot in it and tighten it with a quick jerk from both sides. Fishermen take care not to accidentally let an Overhand Knot form in their line so as not to lose half its strength. Once it’s tied, the knot is difficult to undo. It should only be tied in small cordage or thread if it is not meant to be untied.

THE FIGURE EIGHT SERIES

The figure eight series contains frequently used knots. This series begins by making the crossing turn that would be used for an Overhand Knot, and then increasing the number of times the running end is wrapped around the standing part before passing once through the loop. Twisting this loop an increasing number of times before threading accomplishes the same thing. This series of knots is often used to stop a line from passing through an opening.

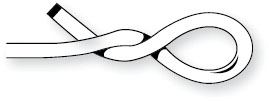

FIGURE EIGHT KNOT

This knot is started like the Overhand Knot, but here the running end makes a complete round turn around the standing part before passing through its loop.

STEP 1 Use the running end to make a crossing turn, and pass the end under the standing part.

STEP 2 Twist the running end up and through the crossing turn.

STEP 3 Tighten the knot by pulling on both ends.

If you wish to use the Figure Eight Knot as a stopper knot, modify Step 2 by pulling the standing part while pressing against the base of the knot on that side. When the Figure Eight Knot and similar stopper knots are tightened this way, the running end will point to the side at a right angle.

The Figure Eight Knot is frequently used as a basis for other knots. It is much easier to untie than the Overhand Knot, and is not as damaging to rope fibers. Because the Figure Eight Knot has a distinctive “figure eight” look, it’s easy to check to make sure it’s tied correctly. This is one of the reasons it is popular with rescue work. It is used on the running rigging of sailboats to keep lines from running all the way through leads and pulleys.

THE MULTIPLE OVERHAND SERIES

The multiple overhand series is made by increasing the number of wraps in the spine of the knot. After making an Overhand Knot, pass the running end through the loop of the knot multiple times, making a different knot in the series every time.

When tied this way, these knots change shape as they are tightened. If you tighten them by pulling on both the running and standing parts, the belly wraps around the spine until all you can see is the barrel shape of these wraps. They can also be tightened by manually wrapping the belly around the spine, which causes the spine to unwrap to a single crossing. These knots have many properties in common, including both high security and difficulty in untying when tightened.

Another way to tie this series is to make the desired number of wraps, and then pass the running end through all of them, leaving it already in its final form. The Double and Triple Overhand Knots are often tied this way. Knots of this series all have a right- and a left-handed version.

These knots are also sometimes called Barrel Knots or Blood Knots—the latter possibly because they were tied to the lashes of a cat-o’-nine-tails to help the flogger draw more blood from his victim. Another version claims the name comes from causing bleeding fingers from tight knots in fishing lines.

WHERE TO START?

Knots in the overhand series are the starting points of many other knots, bends, hitches, and loops. Some bends are made by interlocking Overhand Knots, some hitches are started with an Overhand or Figure Eight, and many friction loops and fishing knots are based on Multiple Overhand Knots.

For the series of stopper knots mentioned here, increasing the number of wraps will not increase their cross-section area. For a wider knot, use a different knot or double the cord first.

There are many advantages to tying knots that are based on others. They are certainly easier to remember because there is so much less to recall. By making it easier to keep many possibilities in mind, you can make better choices for what is needed. When one knot is the basis for another, it is also easier to check your progress as you complete the knot.

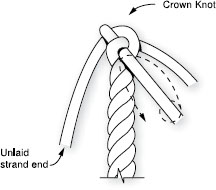

BACK SPLICE

To make a Back Splice, you need to prepare the rope by adding temporary binding where the strands separate out. This is where you will begin making the knot.

STEP 1 Begin the Back Splice by tying a Crown Knot (see following).

STEP 2 Take the first strand and tuck in an over-and-under sequence.

STEP 3 Continue tucks for a minimum of three times.

STEP 4 When you finish, you should have a rope end that looks like this.

The Back Splice Knot is used to keep three-strand rope from fraying and coming apart. If desired, the strands can be partially trimmed after each tuck to taper the splice.

CROWN KNOT

The Crown Knot is very similar to the Wall Knot (see further), except the direction of the running ends, which go down rather than up.

STEP 1 Take the three strands of the rope and tuck each one down through the loop made by another strand.

STEP 2 Tighten the knot by pulling on the strands.

This knot is rarely tied by itself, unless you keep on tying this knot to cover a cylindrical object.

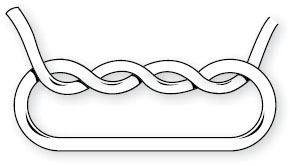

DOUBLE OVERHAND KNOT

This knot is the first in the multiple overhand series. It starts with a Simple Overhand Knot, and then the running end is passed through the crossing turn a second time, making the belly-and-spine appearance you see in Step 1.

STEP 1 Lay down the rope with the running end facing left. Move it down and twist to make the belly, bringing it up over the right side of the standing part.

STEP 2 Run the running end up and under the standing part, making two overhand loops.

STEP 3 Tighten the knot by pulling on both the standing part and the running end.

Twisting the ends in opposite directions will either help the belly wrap around the spine or impede it, depending on which way they are twisted. The Double Overhand, like all knots in the series, is very secure and difficult to untie.

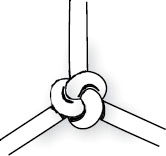

MATTHEW WALKER KNOT

This is another decorative knot that requires separating the rope you’re working with into three strands.

STEP 1 Begin the Matthew Walker Knot by making a Wall Knot (see further), tucking each end up through the next bight.

STEP 2 Continue by making another tuck.

STEP 3 Snug down by pulling each of the strands repeatedly.

Another way to tie the Matthew Walker Knot is to lay the strands in successive Overhand Knots.

STEP 1 Use one strand to make an Overhand Knot.

STEP 2 Continue making Overhand Knots with each consecutive strand.

As you pull on the strands to tighten the knot, make sure you do it gradually and evenly. The outer bights must be coaxed into place to wrap around the knot in the proper form. Gently brush them with your hand to assist them in wrapping all the way around the knot, while gradually and evenly taking out slack.

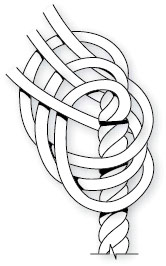

MONKEY’S FIST

The Monkey’s Fist Knot is most frequently used as a heaving knot, and can even be tied around an object to make it heavier. The knot is also popular with children and is used as a decorative knot (see Chapter 11 for more on decorative knots). It is made small to give earrings a nautical look, larger to make key fobs, and larger still to make doorstops. A pair tied to opposite ends of a two-foot cord makes a good cat toy.

Before you start making the knot, estimate the length of line needed by making nine or ten loops of about the size that will be tied.

STEP 1 Make the initial set of three vertical turns.

STEP 2 Hold the turns in place as you add three horizontal turns.

STEP 3 Next, add three turns that go through the middle of the knot, wrapping over the top and around the vertical turns.

STEP 4 Take care that the loops stay in place, and that they continue to stay in place, as you carefully work the slack out through the knot, one turn at a time.

The end can be left long and spliced into the standing part, or tucked into the knot. If the end is to be tucked within the knot, an Oysterman’s Stopper (see Chapter 6) tied in the end will help fill its center. After it is pushed into the middle of the knot, work the slack back to the standing part of the cord.

A variation on the Monkey’s Fist Knot is to use more than three turns. And for the ambitious knot tyer, a three-turn Monkey’s Fist can serve as the center for a five-turn Monkey’s Fist, and so forth, tucking each Monkey’s Fist inside the new one such that lines stay perpendicular.

The Monkey’s Fist can be dangerous if it hits a bystander while throwing it. Sometimes a small bag of sand is used to weight the end of a line if there is a risk of injury.

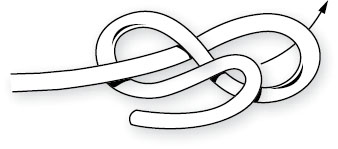

SLIPPED FIGURE EIGHT KNOT

If you want your Figure Eight Knot to release quickly, modify it by making it into a Slipped Figure Eight Knot. This knot is tied from a different version of the Figure Eight Knot.

Use the running end to make a crossing turn by twisting the end down and over the standing part and underneath it. Then, use the bight of the running end to pull it through the loop.

You can release this knot simply by pulling on the running end.

TRIPLE OVERHAND KNOT

This next knot in the multiple overhand series is tied similarly to the Double Overhand, but with three passes through the loop instead of two. When tied this way, it also has the belly-and-spine appearance you see in Step 1.

STEP 1 Tying this knot, you follow the steps described in the Double Overhand Knot (see previous), adding an extra loop at the end.

STEP 2 When you pull on both ends to tighten the knot, the belly will wrap around the spine, giving the knot its final barrel shape when fully tightened.

STEP 3 A popular way to tie this knot is to make the wraps working backward along the standing part, and then passing the running end through all the wraps at once.

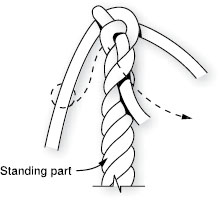

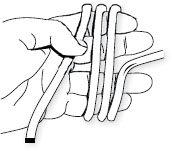

WALL KNOT

Generally, the Wall Knot is not tied on its own, but is the basis for other knots, such as the Wall and Crown Knot, which is made by first tying a Wall and then a Crown Knot (see previous). A continuous set of Wall Knots can cover a cylindrical object.

STEP 1 In order to make the Wall Knot, you’ll need to separate the end of the rope into three strands. Each of the strands is tucked upward through the loop made by another strand.

STEP 2 Tighten the knot by pulling on the strands.

In preparing three-strand rope for multistrand knots, it is best to whip the end of each strand and bind the rope itself with a Constrictor Knot (see Chapter 6) to keep the strands from separating any further down the rope.