KNOTTING TERMS

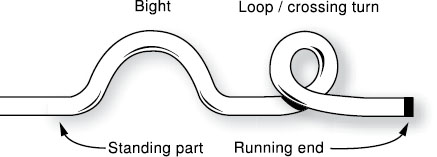

Knowing a few terms for knot tying is very important for following both illustrations and descriptions in the text. When you work with a rope, it generally has a standing part, bight, and running end.

When a knot is tied at the end of a rope, the very tip is referred to as the “running end.” In fishing publications, this section may be referred to as the “tag end.” Using this term in knotting directions gives the important distinction that the very tip of the rope is delivered where the directions say, whether it is over or under another rope, or through a loop of some kind. The other end of the rope—the leading part that is not manipulated in the knot tying—is called the “standing part.”

The term “bight” is the middle part of the rope that is not the running end or standing part. Just as a running end can be directed in many ways in the construction of a knot, a bight can be made out of any part of the rope, and directed the same way. If an arrow in an illustration seems to come from the standing part and not from the running end, it usually means that a bight should be formed and taken in the direction the arrow shows. It may help with some knots to fold the bight over very tight, thus forming a narrow doubled piece that can pass more easily where needed.

THE CROSSING TURN

Another important structure in knot tying is the crossing turn, used in many of the knots you’ll learn in this book. You can quickly create a crossing turn by grabbing a part of the bight and giving it a half twist that forms a loop. When making a crossing turn, it is very important that the orientation of the over-under section of the crossing is correct for the knot you are tying. In practice, you will quickly get the crossing orientation correct each time by associating it with a twist in a certain direction, which is quicker than trying to think about whether the running end crosses over or under when producing it.

HITCHING PRACTICES

When you tie a knot in the rope without ever using the running end, you’re said to “tie in the bight.” Tying in the bight may be done in the middle of the rope or near the end (as long as you’re not moving the running end). For example, you can make a Clove Hitch by making two crossing turns in the bight. Then, lay the right crossing turn over the left one, and the resulting hitch can then be placed over the end of a post.

Many knots that are usually tied with the running end can be tied in the bight by folding a bight anywhere in the line and then using it exactly as you would a running end. When a Simple Overhand Knot is tied this way, the bight that protrudes from the knot where the running end would have been can then be used as a loop. This is a good way to make a loop in very small cord or string.

Another term important in understanding knots is capsizing, which is when a knot changes its shape due to a rearrangement of one of its parts—for example, when you pull on the knot’s loop and it straightens out. If you set up your cord and pull on the running end, it will leave the crossing turn as it straightens and another crossing turn will form on the cord that was running through it. This transformation can happen in knots when they are not snugged down into their proper form, causing the knot to “spill.” In the case of the Square or Reef Knot, this is done intentionally, to untie it more quickly (capsizing is sometimes done on purpose to aid in tying a knot).

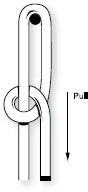

When you’re making hitches, you’ll also come across “turns” and “round turns.” These are two ways of starting a hitch around a ring, bar, or rail. With the turn, the running end is passed just once around the rail, which will allow a transfer of strain from the standing part to the rest of the knot. This may be desirable for some hitches that are better able to hold with strain on them. With the round turn, the extra turn around the rail allows friction to help hold against strain in the standing part, which may help when hitching a rope under strain and takes some of the strain off the knot. The round turn is the first part of the popular hitch called the Round Turn and Two Half Hitches.

TYING OVERHAND

The Overhand Knot and the Multiple Overhand Knot structures are used in many knots, and it is valuable to become familiar with their form. The following illustration shows the shape of a Multiple Overhand Knot of three turns in what is called its “belly-and-spine” form (the belly may also be referred to as the bight).

When you tighten the Multiple Overhand Knot by pulling on both ends, the belly wraps around the spine until it is barrel shaped, as shown here.

THE BEST KNOT FOR THE JOB

When you open a drawer or box of tools, it is immediately obvious that some of them are right and some of them are wrong for the job you have in mind. When you have a job to do with rope, the knots you know will serve you as your toolbox. Just as you would not have much use for a toolbox with just one tool in it, you would not want to do different jobs with rope or string with just one knot. You will want to learn a few different types of knots and learn to use the right one for your application.

The main categories of rope use are joining one rope to another, making a loop, binding, and tying off to an object. Identifying the function that the knot must serve is an important step in choosing one. Some knots are like a multitool in that they can serve a variety of functions, and some are very limited in what they do. A fixed loop will work in several different capacities (for instance, to moor a boat), but a knot like the Reef or Square Knot is unreliable when not used as a binding knot. Once you understand the function of the knot you learn, you will know whether it will work in any particular application.

When choosing a knot for a given application, ask yourself the following questions:

- Will the rope be under steady or changing strain?

- Will it need to be untied?

- Will it need to be tied or untied quickly?

- What knots do I know?

- How secure does it need to be?

- Will others need to tie or untie it?

- Will the tension in the rope need to be adjusted later?

- Will others have to use it?

- Is damaging the rope a concern?

These and many other questions can come into play when you choose a knot. You will, of course, need to limit your choices to which knots you know, just as you must choose from your toolbox only tools that are in it. This leads us to another question you may have been wondering about: “Which knots should I learn?”

CHOOSING WHICH KNOTS TO LEARN

Many people are quite intimidated by the thought of learning more than just a couple of knots, or think that it is difficult or time-consuming. So here are some things to ponder when deciding which ones you want to learn.

The first thing you may wonder about is how many knots you will need to know or what is the smallest number that you can get by on. The number is up to you and may vary depending on your needs. Here is a possible progression you might consider: A loop knot like the Bowline or Overhand Loop can serve a number of different applications, and thus gets you the most mileage from a single knot. Next you should consider learning other knots from different categories, like bends, hitches, and binding knots, so that you can apply them to many situations. It is better still to learn a couple of knots from each category. You might try experimenting with a number of knots within a given category, and settle on the ones you want to remember and use.

Many knots are similar in structure, which means that the more different kinds of knots you learn to make, the easier it’ll be to add new knots to your stock. Because of this, you may decide to choose knots from different categories that have similar structure—you’ll be able to remember them more easily. For example, the multiple overhand structure appears in many knots throughout this book, and so do knots that make use of combinations of Half Hitches.

Taking time to study knot-tying tips and terminology is key to success at learning new knots. Knot-tying practice also helps in following diagrams and in mastering successively complex knots more easily. With a little work, you will have no trouble both tying and teaching many of the different knots in this book. The chapters that follow include many types of knots, and even tips on teaching them and exploring the subject further.