Abel Ferrara occupies an unusual niche within the American underground. Although the edge of his work has continually appealed to downtown underground audiences (he is something of a hero at San Francisco’s Roxy Theater, for example) he has also garnered more mainstream acceptance than the other underground filmmakers to whom he is frequently compared in the alternative press (Nick Zedd, Amos Poe et al.). For this reason, his work – or at least its reception – highlights many of the tensions surrounding the dividing line between avant-garde, underground film and the cinema derisively labelled ‘indiewood’ by downtown cinema fans.

The Addiction (1995) stands as something of an interesting anomaly in Ferrara’s oeuvre. A vampire film peppered with references to Nietzsche, Beckett, the My Lai massacre and Burroughs, the film seemed tailor-made to appeal to both an underground and a mainstream audience. But, as Xavier Mendik points out:

Mainstream critical reaction to The Addiction was at best mixed. Although writers such as Gavin Smith [Sight and Sound] praised the complex nature of the film’s construction and style, the narrative’s continual shift from scenes of excess ‘necking’ to narrations on Nietzsche frequently lead to claims that it was both pretentious and greatly distilled its reading of European philosophy.1

While the much tamer Wolf (Mike Nichols, 1994) was praised in the mainstream press for its implicit critique of corporate downsizing and capitalist greed, The Addiction’s explicit retooling of vampirism as another example of Burroughs’ junk pyramid did not elicit the critical commentary it deserved.

The film that should have cemented Ferrara’s status with both mainstream ‘independent’ and underground audiences, then, had the reverse effect of solidifying his status as a primarily underground director. The very things that made The Addiction a difficult viewing experience for mainstream critics endeared it to underground audiences. As Tom Charity notes:

This is one wild, weird, wired movie, the kind that really shouldn’t be seen before midnight.… Shot in b/w, with an effectively murky jungle/funk/rap score, this is the vampire movie we’ve been waiting for: a reactionary urban-horror flick that truly has the ailing pulse of the time. AIDS and drug addiction are points of reference, but they’re symptoms, not the cause.… Scary, funny, magnificently risible, this could be the most pretentious B-movie ever – and I mean that as a compliment.2

In this essay, I plan to discuss the significance of The Addiction’s success as an underground film and to analyse the way it retools vampirism as addiction, economy and power. As the subtitle indicates, I am particularly interested in the way the film uses theory to get its point across. Because of its ‘narrations on Nietzsche’, The Addiction belongs to a growing body of underground work which I have described elsewhere as ‘theoretical fictions’, the kind of fiction in which ‘theory becomes an intrinsic part of the “plot”, a mover and shaker in the fictional universe created by the author’.3

It is the prominent position of theory in The Addiction which made reviewers on opposing sides of the cultural divide label the film as ‘pretentious’ (a word that took on both derisive and celebratory nuances, depending on the user’s cultural point of reference). It is the prominent position within the film of a theoretical discourse that intellectuals critiqued (for greatly distilling a reading of European philosophy) which problematises some of the assumptions that academics tend to make about the cultural uses of theory itself. Like Charity, I think this is ‘one wild, weird, wired movie,’ the vampire movie underground audiences have been waiting for. I hope in this article to demonstrate why.

The film begins with a philosophy lecture on the My Lai massacre – a series of atrocity slides with a voiceover explaining when the attack occurred, what happened in that place and the nature of US national reaction to the horror. As Kathleen (Lili Taylor) and her friend Jean (Edie Falco) leave the lecture, they discuss the central moral problem which the My Lai trial of Lt. Calley seems to illustrate. That is: how can you hold one man responsible for the crimes and guilt of an entire nation, and how do you separate what happened at My Lai from what happened during the rest of the Vietnam War? ‘What do you want me to say?’ Jean asks Kathleen. ‘The system’s not perfect.’ As Kathleen leaves her friend, she encounters a woman dressed in an evening gown (‘Casanova’, played by Annabella Sciorra), a real vamp who drags her into a subway station and bites her neck.

There is a certain grim logic in going from one kind of bloodlust (war crimes) to another (vampirism) here. And there is a way in which the hunger for blood – in all its manifestations – is disturbingly figured in the film as addiction. Throughout the movie, Kathleen keeps returning to images of atrocity – an exhibition of Holocaust photographs, documentary footage of a massacre on the evening news. In part, this continual return serves to remind us of the ethical questions posed at the beginning of the film. Who exactly is responsible for this constant replay of inhumane violence and brutality? To what extent are we all complicit in a world system which seems to need blood as much as vampires do? But, as the last question suggests, Kathleen’s continual return to a kind of ‘primal scene’ of historic atrocity also serves to link war crimes – crimes against humanity – to a trope of physical dependency and sickness, vampirism. ‘Our addiction is evil,’ Kathleen says at one point, meaning that our addiction is to evil, as well as being evil in and of itself. ‘The propensity for this evil lies in our weakness before it,’ she continues. ‘You reach a point where you are forced to face your own needs and the fact that you can’t terminate the situation settles on you with full force.’

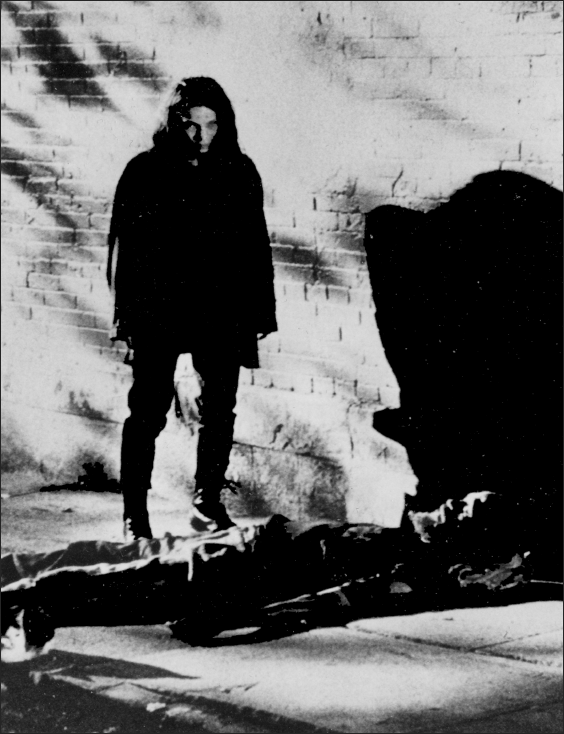

If war crimes are linked to vampirism and addiction, blood itself is continually linked to junk. This is most clearly manifest in Kathleen’s emerging vampiric ‘hunger’, as the need for a ‘fix’ makes her physically ill and as the lines between the substances of blood and narcotics are continually blurred. Kathleen’s first ‘fix’ is literally that – a fix. Walking down the street, she sees a junkie with a needle still in his arm. She draws blood up into the syringe, and once home shoots this blood-drug mix into her vein. Later, she initiates her graduate advisor into vampirism by seducing him first with drugs. Inviting him to her apartment, she kisses him and then disappears into the kitchen to fix ‘drinks’. What she brings out, however, is a tray with two syringes, a candle and a spoon. ‘Dependency is a wonderful thing,’ she tells him. ‘It does more for the soul than any formulation of doctoral material. Indulge me.’ It is only later, after he has succumbed to one potentially addictive substance, that she takes a bite out of his neck and turns him into a vampire. And Peina (Christopher Walken), the vampire ‘guide’ Kathleen encounters in the street, continually conflates the language of blood with that of drugs. He mixes terms like ‘fasting’ with ‘shooting up’ to describe his attempts to control ‘the hunger’, and pointedly asks Kathleen if she has read William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch.

FIGURE 3 Kathleen gets a fix in The Addiction

The repeated commingling of blood and junk, as well as the direct reference to Naked Lunch, invites the viewer to ‘read’ vampirism in The Addiction as yet another example of Burroughs’ ‘Algebra of Need’. In the Preface to Naked Lunch, Burroughs draws a picture of what he terms the ‘junk pyramid’, in which the traffic in heroin – and here, blood – becomes the distilled model of the entire capitalist system. The idea is to ‘hook’ the consumer on a product that s/he does not initially need, in the secure knowledge that once hooked the buyer will return for ever-increasing doses. Burroughs writes:

I have seen the exact manner in which the junk virus operates through fifteen years of addiction. The pyramid of junk, one level eating the level below (it is no accident that junk higher-ups are always fat and the addict in the street is always thin) right up to the top or tops since there are many junk pyramids feeding on the peoples of the world and all built on the basic principles of monopoly: 1) Never give anything away for nothing; 2) Never give more than you have to give (always catch the buyer hungry and always make him wait); 3) Always take everything back if you possibly can. The Pusher always gets it all back. The addict needs more and more junk to maintain a human form… buy off the Monkey.4

The analogy which Burroughs draws between addiction, capitalism, evil and power in Naked Lunch is drawn in The Addiction as well. Like many US urban universities, the university which Kathleen and Jean attend is located in the heart of what we euphemistically call the ‘inner city’ (the film was shot in and around New York University’s Washington Square, before it was ‘cleaned up’). An enclave of privilege, it is surrounded by streets that stand – as Robert Siegle points out – ‘as one of the most potent demystifiers of the illusions in which most of us live’.5 The economy here is based, it seems, on junk. The first time we see Kathleen walk down the street, young men approach her, hoping she will buy, and ‘I want to get high, so high’ plays on the soundtrack. It is in these mean streets that Kathleen is first accosted and then turned into a vampire, and it is to this neighbourhood – as well as to the University itself – that she continually returns, looking for blood.

The geographic construction of Ferrara’s New York is a junk pyramid, then, with the higher-up ‘pushers’ – those who push knowledge and a certain ideology – living off the addicts in the street. In case we do not get the economic/class point, Ferrara includes a doctoral dissertation defence party that plays like some vampiric reworking of May 1968, where the working class and student hordes rise up to attack the power elite. After successfully defending her doctoral thesis, Kathleen invites the faculty to a small gathering at her home. There, the loose coalition of vampire students, street people and one ‘re-formed’ graduate advisor, stage a blood bath – as they gorge themselves on professors and ‘unturned’ students. The class barriers between the University and the streets break down as soon as the underclass unmasks itself at Kathleen’s party, and begins drawing blood.

The subsequent vampire banquet is both a revolt and a final levelling of class structure. ‘The face of “evil”,’ Burroughs writes, ‘is the face of total need.’6 One of the disturbing things about this film is its insistence that reducing everyone to the ‘total need’ level of the addict on the street is a necessary precursor to meaningful sociopolitical, economic change. As Peina darkly tells Kathleen, the first step toward finding out what we really are is to learn ‘what Hunger is.’

THE WILL TO POWER

If blood/junk ‘is the mould of monopoly and possession’, as Burroughs asserts in Naked Lunch,7 it is also – as Allen Ginsberg testified at the Naked Lunch trial – ‘a model for… addiction to power or addiction to controlling other people by having power over them.’8 In The Addiction, Ferrara makes this explicit by substituting tropes of domination for the traditional vampiric trope of seduction. ‘It makes no difference what I do, whether I draw blood or not,’ Kathleen thinks as she gets ready for a vamp-date with her thesis advisor. ‘It’s the violence of my will against theirs.’ The fascistic nature of vampirism is hammered home early in the film with the pointed use of a sound bridge. In a key scene shortly after she has been bitten, Kathleen goes to an exhibit of Holocaust photographs at the University Museum with her friend Jean. A speech by Hitler plays in the background. In the next shot, Kathleen is slumped on the floor of her apartment – in a posture we have come to associate with her vampiric sickness. We still hear Hitler’s voice, echoing now, it seems, in her head. In the next shot, she is on the street, looking for blood.

While vampirism is cinematically linked to a Nietzschean ‘will to power’, the vampiric attack itself is figured as existential drama. Most vampiric encounters in The Addiction begin with a pointed invocation of individual responsibility. ‘Look at me and tell me to go away,’ the vampire tells the victim. ‘Don’t ask, tell me.’ And when the victim – overcome and traumatised by the violence of the unexpected attack – asks the vampire to leave her (usually her) alone, the vampire is quick to assign blame. ‘What the hell were you thinking?’ Kathleen asks an anthropology student. ‘Why didn’t you tell me to get lost like you really meant it?’ When Kathleen herself is first bitten by Casanova, she is called a ‘fucking coward’ and ‘collaborator’.

The question of who bears responsibility for the vampiric attack mirrors the ethical questions surrounding the prosecution of Lt. Calley, raised in the opening scenes of the film. Only here it is not the entire nation that stands culpable for war crimes, but the victim herself – the ‘fucking coward’, the ‘collaborator’ – who is somehow responsible for her own victimisation. The fact that so many of these victims are women and that they are seemingly punished for being too polite, too nice, too passive, only adds to the discomfort that many viewers experience watching a movie which – in the words of J. Hoberman – ‘insists on blaming the victim.’9

Furthermore, there are the recurring shots of atrocity photos within the film itself – shots of the My Lai massacre, the Holocaust, Bosnia – which only serve to increase the ethical stakes of raising the responsibility question at all. Are these victims, too, responsible for what happened to them? Were they too nice, too passive in the face of American/German/Serb aggression? In the face of such horrific brutality, does it even make sense to ask who is responsible, who holds the moral high ground?

Yet the film consistently does invite us to ask the question. The ongoing philosophical quarrel in the film – raised repeatedly by different characters – is the old quarrel between determinism and existentialism, the old dilemma governing the kind of guilt we choose to embrace. Are we evil because of the evil we do, or do we do evil because we are, in the last analysis, evil? In the universe of the film, the constant presence of evil is the only issue on which all Western philosophers seem to agree. Before biting Jean, for example, Kathleen pointedly sets an impossible philosophical task: ‘Prove there’s no evil and you can go.’

What made so many critics and reviewers uncomfortable about watching this film, then, is precisely what was supposed to make them feel uncomfortable. The Addiction mounts what Avital Ronell has called a ‘narcoanalysis’ of society, that is, a mode of analysis in which ‘substance abuse’ and ‘addiction’ name ‘the structure that is philosophically and metaphysically at the basis of our culture.’10 ‘Addiction,’ Ronell writes, ‘has everything to do with the bad conscience of our era.’11 To get the point of Ferrara’s film, one need only add ‘vampirism’ to ‘addiction’ in the above quote.

THE STATUS OF THEORY

As most critics note, theory and theoretical discourse are a heavy presence in the film. This is usually credited to the fact that Kathleen is a philosophy graduate student and that much of the film is set in academe. What is interesting, however, is that Kathleen does not really start speaking theoryspeak until after she has been bitten. When she discusses Lt. Calley’s case with her friend and fellow graduate student, Jean, in the opening sequences of the movie, she formulates questions using much the same language that any savvy watcher of the six o’clock news might use:

The whole country, they were all guilty. How can you single out one man? How did he get over there? Who put the gun in his hand? They say he was guilty of killing women and babies. How many bombs were dropped that did the exact same thing?

Once bitten, however, her manner of speaking begins to change. When she runs into Jean after her long absence from school, Jean asks if the infirmary gave her ‘something to take’. ‘Medicine’s just an extended metaphor for omnipotence,’ Kathleen answers. ‘They gave me antibiotics.’ In fact, in this film the emergence of theoryspeak becomes another sign that someone is ‘turning’; like loss of appetite and aversion to sunlight, it is a sign that the vampire virus is at work.

Like any sickness or physical addiction, the vampire virus plunges Kathleen into an awareness of the absolute materiality of the body. Soon after she has been bitten, she has to leave a philosophy lecture on determinism and rush to the bathroom, where she vomits blood. After she is released from the infirmary she begins to question the wisdom of doing a dissertation on philosophers who ‘are all liars’. ‘Let them rot with cancer,’ she tells Jean, ‘and we’ll see what they have to say about free will.’ The emergence of theoryspeak, then, seems to coincide with an awareness of mortality, of the absolute materiality of life. This is perhaps odd in a film that is also so resolutely and unabashedly metaphysical. But it foreshadows one of the important distinctions that the film insists on making between ‘academic’ philosophy and the theoryspeak of real life.

There are two textual canons which are given to Kathleen in the course of the film. The first is, of course, the reading list for her philosophy seminar: Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, Heidegger’s Being and Time, Husserl, Kierkegaard’s Sickness Unto Death, Nietzsche’s Will to Power. The list always gets a laugh from the audience, since the titles seem to play like double entendres – a further indication of the ways in which vampirism is categorically linked to existential despair (‘sickness unto death’) as the key sickness-metaphor of the time. This canon is not much use to Kathleen, however, as she tries to manage living-with-vampirism. So, she is in pretty bad shape when she meets Peina, who tries to teach her how to control the hunger.

Kathleen’s encounter with Peina is one of the crucial episodes of the film and central to their interaction is the fact that Peina operates according to a canonical logic of substitution and contamination. That is, Peina provides both an alternative canon and a deconstructive means for reading the old one. ‘Have you read Naked Lunch?’ Peina asks Kathleen early in their encounter. ‘Burroughs perfectly describes what it’s like to go without a fix.’ Later he tells her again: ‘Read the books. Sartre, Beckett. Who do you think they’re talking about? You think they’re works of fiction? “I felt the wind of the wings of madness” – Baudelaire.’ He also cites Nietzsche. ‘You think Nietzsche understood something? Mankind has striven to exist beyond good and evil from the beginning. You know what they found? Me.’ This is the vampire who will later drain Kathleen dry in order to teach her about pain and reveal her true nature.

With the exception of Sartre and Nietzsche, who appear on Kathleen’s philosophy seminar syllabus, the works in Peina’s canon are associated with literature; all the texts he mentions are works that have been privileged by those who ‘do’ theory – Kristeva, Cixous, Derrida, Ronell. Here, they emerge not only as key texts for Kathleen’s survival (‘Who do you think they’re talking about? You think they’re works of fiction?’), but as key texts for ‘reading’ philosophy. It is after her encounter with Peina that Kathleen begins serious work on her dissertation, which seeks to reposition the philosopher him/herself in the text. ‘Philosophy is propaganda,’ she tells her dissertation committee:

There is always the attempt to influence the object. The real question is what is the philosopher’s impact on other egos.… Essence is revealed through praxis. The philosopher’s words, his ideas, his actions cannot be separated from his value, his meaning. That’s what it’s all about, isn’t it? Our impact on other egos.

Kathleen’s dissertation comes down, then, on the side of existentialism (‘essence is revealed through praxis’), which she insists on reading through a vampiro-theoretical lens (‘philosophy is propaganda’). More importantly, however, the fact that she writes the dissertation after her encounter with Peina – an encounter which marks her painful initiation into theory and into learning the nature of the hunger – recalls the link between drugs (addiction) and writing that Derrida sees in the pharmakon. Certainly the writing pours out of her at this point, as she tries to deal with ‘a metaphysical burden and a history’ which, Derrida tells us, ‘we must never stop questioning’.12

As even this sketchy outline will show, Ferrara does not supply the viewer with a neat theoretical package, a logical argument leading to one final conclusion. Given the often contradictory discursive theoretical registers invoked during the course of the film, it is easy to see why academics disliked what they saw as a reductive reading of European philosophy and theory. And just as easy to see why people with no theoretical background at all might find the film ‘pretentious’ or confusing. But the very split which the film posits – the split between academic philosophy and a kind of savvy streetwise theory (where the real teachers emerge from the shadows) – is reflected in the reception the film received from underground, as opposed to academic, audiences. In fact, The Addiction’s positive reception as an underground film problematises some of the assumptions that academics tend to make about the cultural uses of theory itself.

A quick glance at alternative culture productions and publications (Bomb, CTheory, and the Frameworks Online Experimental Filmmakers listserv, for example) reveals that many of the distinctions academics routinely make between academic discourse (particularly theoretical discourse) and ‘lay’ discourse are problematic. People outside the academy read theory and they use it as an intrinsic part of their work – they do not always read it the same way academics do, and they certainly use it differently, but the received wisdom that only academics can understand theoretical language or concepts simply is not true.

To take one example, there are strong connections between poststructuralist theory and techno/electronic music. DJ Spooky – an African-American spin master whose real name is Paul Miller – has done gigs with Baudrillard, for example, and talks about DJing as a mode of deconstruction. One of the German labels that regularly records American DJs is called Mille Plateaus; it was specifically named after the famous work by Deleuze and Guattari – and one of its best selling compilation CDs is a memoriam for Gilles Deleuze.13

Within the experimental work of late twentieth-century culture there is a whole cultural formation that deals with theory in ways that mean we are ultimately going to have to redefine what we call theory – what counts as theory. There are a lot of works – literary, artistic, musical and cinematic/video – that I am beginning to call ‘theoretical art’. It is the audience for particularly this kind of underground theoretical culture which responded so positively to Ferrara’s film – who laughed out loud at the funniest academic pretences of The Addiction and did not find its theoretical contradictions disturbing at all.

REDEMPTION OR THE SEVENTH CIRCLE

The end of The Addiction is notoriously hard to read. It does not follow the formulaic folklore pattern that Carol Clover ascribes to most contemporary horror; that is, it does not seem to restore order.14 Or rather, it restores order, but it is difficult to say exactly what kind of order is being restored. In the words of one reviewer:

After the grand guignol hilarity of a faculty party/bloodfeast, Ferrara has the guts to go for the jugular. The final scenes of The Addiction are religious in the most unforgiving sense of the word; once again, Ferrara writes as a soul doomed to redemption.15

Following the bloodfeast, Kathleen is sick from overeating. Stumbling down the street, smeared with blood, she is taken to a nearby Catholic hospital by a good Samaritan. Once admitted to a room, she asks the nurse to let her die. When the nurse assures her that nobody is going to let her die, Kathleen asks her caregiver to open the blinds and let in the sunlight.

So far, so good. This is classic vampire movie fare, where we expect to see the vampire go up in a puff of smoke (as Christopher Lee does at the end of Terence Fisher’s 1958 film, Horror of Dracula). As soon as the nurse leaves, however, and Kathleen begins to pant and moan, the room suddenly darkens as the blinds quickly close. There is a cloud of smoke all right, but it is coming from Casanova’s cigarette. ‘The Seventh Circle, huh?’ she asks Kathleen. ‘Dante described it perfectly. Bleeding trees waiting for Judgement Day, when we can all hang ourselves from our own branches. It’s not that easy.’ Casanova leaves Kathleen’s room; a few minutes later a priest enters. The credits reveal that this is Father Robert Castle, who also provides the voiceover narration for the My Lai sequence which opens the film. Father Castle hears Kathleen’s confession (her acknowledgement of guilt and request for forgiveness). Shortly thereafter we see Kathleen’s grave. A woman, dressed in lightly coloured slacks and blouse, her hair neatly pulled away from her face, is standing in front of the grave. It is Kathleen. She puts a flower on the gravesite. In voiceover narration, she says ‘to face what we are in the end, we stand before the light and our true nature is revealed. Self revelation is annihilation of self.’ She leaves the churchyard and the screen goes black. The credits roll.

On one level, this seems to be a nod to Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976), whose shock graveside ending established the pattern for many horror movies to come. Only here, the Final Girl who survives the school party-turned-bloodbath is not the altruistic good girl who encouraged her boyfriend to take the school’s dowdy scapegoat to the prom. Rather, it is a reconstructed and resurrected vampire who appears to have finally learned, in Peina’s words, to control the hunger, blend in and ‘survive on a little’.

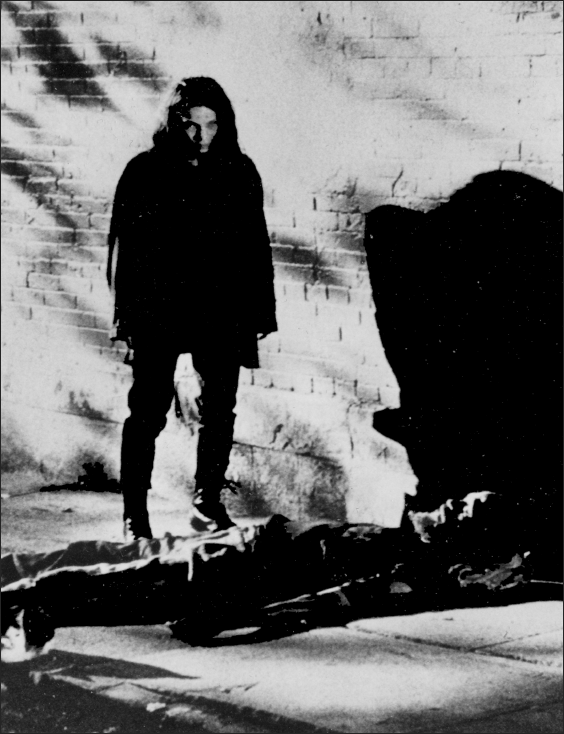

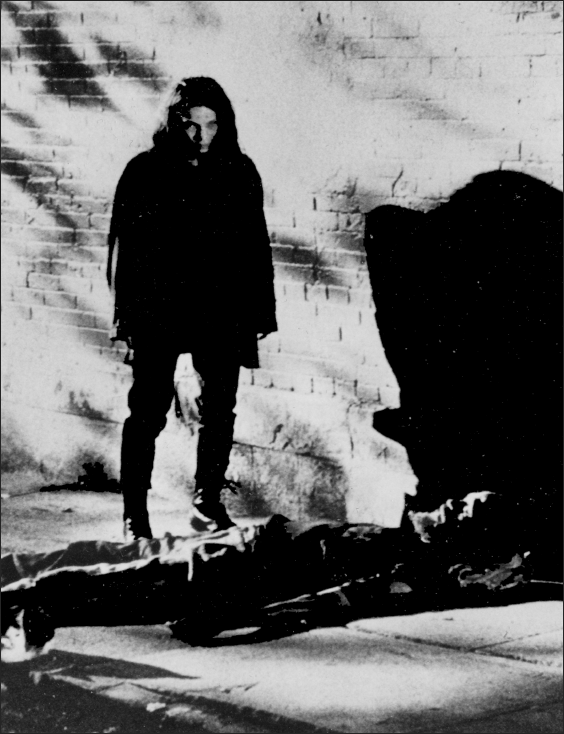

On another level, however, this scene is, as Peter Keough maintains, ‘religious in the most unforgiving sense of the word.’ Kathleen’s assertion that ‘self-revelation is annihilation of self’ seems a repudiation of the arguments she made during her dissertation defense: ‘That’s what it’s all about, isn’t it? Our impact on other egos.’

FIGURE 4 Elegant evil: Casanova at the blood feast in The Addiction

Here, by way of contrast, she seems to be moving toward the kind of Christian mysticism espoused by Simone Weil – a woman so dedicated to tearing down her ego that she literally starved to death. ‘If the “I” is the only thing we truly own,’ Weil wrote, ‘we must destroy it. Use the “I” to tear down the “I”.’16 As if this were not already confusing enough, the music which plays on the soundtrack during this sequence is an instrumental piece, ‘Eine Sylvesternacht’ (a New Year’s Eve Night), beautifully played by Joshua Bell and composed by the ‘beyond good and evil’ philosopher himself, Friedrich Nietzsche.

If the ending is perplexing, it is appropriate. One of the major stylistic aspects of The Addiction is its trompe l’oeil visuals, in which perspective – both historical/empirical and ethical – is repeatedly called into question. From the earliest shots in which we watch Kathleen watching, we are constantly challenged to think about perspective, to wonder whose point of view we are occupying and/or what exactly it is we are seeing. This emerges most pointedly in confusing or trompe l’oeil shots, the first of which occurs shortly before Kathleen encounters Casanova. As Kathleen walks down Bleecker Street, the screen goes black. Then we get what first appears to be a wipe, moving left to right. But there is a funny ‘hook’ at the bottom of the screen, the edge of a building, indicating that this is not a wipe, but a lateral tracking shot (right to left). Someone is coming from the shadows of a building, but who? Not Casanova, whom we see in long shot. Not Kathleen. This kind of Eye of God, point-of-view shot recurs several times during the course of the film, helping to visually establish a mystical/religious feel to the whole movie.

In addition, what appear initially to be unattributed associational shots/edits invite comparisons between vampirism and real brutality. This happens most frequently in the shots which show atrocity photographs. When Kathleen goes home with the anthropology student, for example, we see the women cross the street together. Then we get a shot of mutilated bodies. It takes a while before we realise that this is news coverage of Bosnia which Kathleen, blood still smeared on her lips, is watching on television – not a slaughter which she herself carried out.

Ferrara also repeatedly challenges traditional expectations of space. The scene during which Kathleen is working on her dissertation unravels as a lateral tracking journey through space and time. But here Kathleen seems to be literally butting heads with herself, as she appears frame left (facing right) in one shot and frame right (facing left) in the shot immediately following. Finally, Peina’s loft is an impossibly ethereal space. At once tiny apartment and cavernous loft, it changes shape and dimension, depending on the framing of each shot (there is a curious shot in which words appear on a wall behind Kathleen, a shot which somehow simultaneously invokes an art gallery, church and street graffiti). It is also notable that it is hard to tell where exactly in the city Peina’s loft is located; ‘someplace dark’, he tells Kathleen.

The fact that we are not continually exclaiming at these jumps and shifts, as we might during a Godard film, is a function of both the way we watch horror and of Ferrara’s genius for apparent continuity. But it is a mistake to read the confusing nature of the film’s end as somehow different from what came before. If this film is about anything, it is about the fact that – as Peina tells Kathleen – we are nothing, we know nothing; nothing, that is, except the fear of our own death.

It is interesting that the final ‘word’ of the movie – the song that plays on the soundtrack as the credits roll – takes us back to the opening sequences of the film (My Lai and our responsibility to and for the world). ‘Eine Sylvesternacht’ segues into a rap song about black-on-black violence, and the film ends with the vampire refrain ‘forever is a long time’.

CONCLUSION

‘Every age embraces the vampire it needs,’ the book jacket copy for Nina Auerbach’s Our Vampires, Ourselves proclaims.17 This applies not only to ages, but also to subcultures within each age. For while it is true that The Addiction had ‘the ailing pulse’ of its time, as Tom Charity wrote, it is also true that it did not find popularity among a mainstream independent or horror niche market. Instead it drew its audience from the underground, from a subculture of viewers who were not put off by its peculiar drug-theory blend, or obtuse vocabulary, or pointed socio-economic commentary. And while it did not cement Ferrara’s reputation with a mainstream ‘indie’ crowd, it did extend his fan base within the underground itself. The Addiction is an alt.film Goth lover’s delight, and so patrons (particularly women) who had not been attracted to Ferrara’s earlier work found him through this ‘vampire tale told Ferrara style’.18

The film that should have cemented Ferrara’s status with both mainstream independent and underground audiences, then, had the reverse effect of solidifying his status as a primarily underground director. But it also expanded his fan base within the underground, extending it beyond the audience for films like Bad Lieutenant (1992) to the audience for films like Nadja (Michael Almereyda, 1994) and the ever-popular Night of the Living Dead (George A. Romero, 1968). Its visually arresting style and ‘wild weird wired’ story confirmed Ferrara’s reputation as ‘one of contemporary American cinema’s most challenging and consistently innovative underground directors’.19 Finally, its ‘narrations on Nietzsche’ helped to situate Ferrara within a larger downtown artistic tradition (‘theoretical fictions’) that was already trading heavily on theory. For all these reasons, it has emerged as a key text in the history of contemporary underground US cinema. It is also, as I hope I have shown, a spectacular film. As Peina might say, ‘See it. Read the books.’

Special thanks to Chris Dumas, Nicky Evans, Skip Hawkins, Xavier Mendik, Steven Schneider and the students in my graduate horror seminar (C592).