Irena: Where’ve you been?

Lesley: Where’ve I been? Around the world in eighty ways, that’s where.

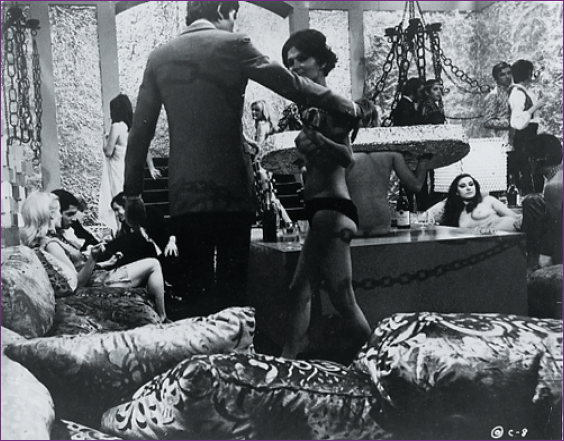

The Alley Cats (1966)

It is now a commonplace to view the 1960s as marked by the public sphere’s saturation with sexual representations. These were representations that had up until that time only circulated within underground, marginal viewing spaces. The debates which coalesced around this putatively pornographic visibility were concerned as much with questions of taste and the exceedingly blurred boundaries between art and obscenity as with the possible responses of an untrained ‘low-brow’ public to the products of savvy sexual entrepreneurs and ‘smut peddlers’. One such place where the shift from underground to ‘above ground’ occurred was in the genres and cycles of the sexploitation film. Independent filmmakers such as Russ Meyer, Herschell Gordon Lewis, Doris Wishman, Michael and Roberta Findlay, Andy Milligan and many others produced profitable cycles of nudies, roughies and kinkies to capitalise on the inability of the courts to empirically define and legislate against obscenity.1

Marked by their low budgets, oppositional stance towards Hollywood, amateur (if not ‘impoverished’) aesthetics and ‘crude’ transcriptions of dystopian sexual fantasy, simulated violence and soft-core sex, sexploitation films provide a shadow history to the cultural and social events of the turbulent 1960s. As ‘the capitalist impulse seized upon sexual desire as an unmet need that the marketplace could fill’,2 sexploitation films deployed a rhetoric of erotic consumption made prevalent in the public sphere of the 1960s.

The film work of Radley Metzger plays a significant role in the history of this independent mode of production. This is because it mediates between the high culture status of the foreign art film and the rough-hewn, low-cult material of the sexploitation feature. Metzger’s work can be seen in terms of its attempts to dissociate from its sexploitation neighbours through a process of cultural distinction, mapping the move from underground to aboveground along an axis of sexual, and cinephile, taste. Shot in Europe with European actors on lavish and ‘cultured’ locations, Metzger’s cinema of the 1960s attempted to school its public in the erotic pedagogy of continental life.

Bringing ‘art-house’ legitimacy to the economic and narrative degradations of the American sexploitation film industry were films such as The Dirty Girls (1964), The Alley Cats (1966), Carmen Baby (1967), Therese and Isabelle (1967), Camille 2000 (1969), The Lickerish Quartet (1970) and Score (1972). With these works, the director introduced a component of market segmentation into the field of erotic consumption. Metzger’s talent as a ‘creative distributor’ facilitated the importing of European films with sexually suggestive content – films such as the infamously auto-erotic I, A Woman (1966), as well as The Fourth Sex (1961), The Twilight Girls (1956), Sexus (1964), The Frightened Woman (1968) and The Libertine (1969) – to American theatres.

HISTORY, INDUSTRY, RECEPTION

Metzger began his career in films as an editor, with a brief stint as a film censor, cutting out offensive footage from Bitter Rice (1948) for RKO. He moved on to editing and making trailers at Janus Films, a major distributor of European art cinema. European films had garnered a substantial audience in American cities in the late 1940s and early 1950s in the emergent exhibition context of the art-house theatre.3 After making the relatively unsuccessful film Dark Odyssey (1959), about Greek immigrants in New York City, Metzger decided to start a distribution company with Janus co-worker Ava Leighton, which they named Audubon Films. The 1960s began with the buying of US rights to risqué European films, repackaging them – via dubbing, liberal editing and sensational ad campaigns – before distributing them in art-houses in urban and suburban locales. The Danish I, A Woman (1966), directed by Mac Ahlberg, concerning the unsatisfied and auto-erotic desire of a young woman played by Essy Persson, was the most successful and notorious of these imports. It was credited with expanding the contexts in which erotic films could be screened in the United States, prior to Vilgot Sjoman’s controversial I am Curious [Yellow] (1969). Exemplary of the Audubon art-porn hybrid aesthetic, I, A Woman was seen to ‘break down the distinction between sex-violence films and conventional films’.4 This breaking of barriers came at a price, as Metzger’s soft-core films can be understood as setting the scene for the emergent circumstances of hard-core ‘porno-chic’ in the early 1970s by validating, for audiences, the exhibition of sexual content in more conventional theatres.

In the mid- to late 1960s, when the availability of European product dried up due to more stringent censorship codes established in Europe, Metzger, while still importing films, shifted gear and began filming his own features in extravagant continental settings such as mansions, castles and swish European apartments, with cast and crews culled from other European productions. Renowned cinematographer Hans Jura worked with Metzger on a number of films, including Therese and Isabelle and The Alley Cats, giving the films a glossy aesthetic which utilised processes as Ultrascope and 3 strip Technicolor. As the decade progressed, Metzger’s budgets grew larger, from five to six figure sums. As a result, his features took up the florid and modern excesses of 1960s fashion via set design and costume to impart a polished and streamlined look to his filmic locations and his characters’ upper-class lifestyles. Many of the films were adapted from novels, short stories and plays, according to Metzger a compensation for his lack of skills as a storyteller.5 Score, filmed in 1972, was the bridge between Metzger’s soft-core and hard-core product, the latter directed under the pseudonym of Henry Paris.

Metzger’s studied cinephilia, garnered from years of his editing work, film viewing and childhood bouts in the summer air conditioning of New York City movie theatres, found an apt object in the aesthetic and editorial construction of his films. The logic of the cut, a mark of the censors classification and judgement as well as of the manipulation of flow, movement and economies of visual desire, defined the cinema of Metzger in both his authored and ‘curated’ projects. Metzger himself claimed, in allegiance with the marketing angle, ‘I’m never going to make a shot that I couldn’t use in the trailer. And I think that rule gives the scenes an intrinsic movement.’6

This stylistic and conceptual synthesis of the commodity status of the cinema with its new cultural value as art, not only exemplifies the ethos of the sexploitation film, but also speaks to the particular predicament of the American cinema at the crossroads of the 1960s. Specifically, one granted free speech protection by the 1952 Miracle case, and capable of enlightenment, yet still bound to the travails of the free market.7 The film trailer, the lynchpin of the sexploitation industry’s appeals to its audience and mode of address, held the key to the experience of sexually explicit films, as one of condensation. Vincent Canby noted that ‘exhibitors of these film find that the trailers advertising their coming attractions are as eagerly awaited as the feature films. On one Monday night, a Manhattan sex-violence house devoted no fewer than 20 minutes to its trailers for future films.’8

We can look at one of Metzger’s own trailers to see their effectiveness in condensing a cinematic experience and promising pleasures ahead. In the trailer for The Alley Cats, Metzger’s editing style – reused in the Camille 2000 trailer – stacks a series of quickly-cut freeze frames from the film in a synchronised crescendo, a movement which is arrested by the intruding flow of the moving image. This stop and start method, in which sexual scenarios are catalogued and archived as cinephilic moments or screen memories of auratic female sexuality, stilled and put in motion, reveals all of the narrative and spectacular trajectories of the film itself. The condensation of sexual action, and the condensation of the action of the film into a commodity form, itself enacts a certain mnemonic function at the same time that it provides promise of a future ahead of it, of footage that will exceed what has been shown. The finale, which zooms in staggered fashion on main character Leslie’s (Anne Arthur) face and parted mouth, with moaning voiceover, seems to presage the facial displacements of the hard-core genre that would soon follow. Signaling a kind of completion in the aural acquisition of female orgasm, the double play on ‘COMING!’ and ‘COMING ATTRACTIONS’ performs a textual joke on the structure of the trailer itself and the temporal structure of viewer desire. Metzger’s success can thus be partly attributed to his creative and skillful workings of the art-erotica hybrid in all arenas of film production, promotion and distribution.

The lesson of the economic success of independents such as Metzger and the lesser-budgeted sexploitation mavericks was not lost on the major Hollywood studios. In an attempt to alleviate its economic slump, Hollywood began to compete with sexploitation features, art-house films, foreign imports, underground and experimental films and independent films for a share of the commercially lucrative arena in sexual suggestiveness.9 By the latter part of the 1960s, Metzger was complaining of the danger Hollywood’s poaching strategies posed to his business, as he asked, ‘How can we compete with Elizabeth Taylor’s dialogue in Virginia Woolf or undraped stars in many big-budget films with our unfamiliar starlets?’10 Positing difference and distance from the rabble of sexploitation in the aspirational trajectory towards a more middle-class audience did not necessarily alleviate the fuzzier distinctions between Camille, Carmen, Therese et al. and the majors.

At a point when sexualised narratives and Hollywood features with ‘mature’ themes seemed to blur the lines between ‘smut’ divined by community standards and ‘film art’, Metzger’s ‘high class’ productions introduced distinction in their upper class pedigree and representations of the sex lives of the decadent bourgeoisie. The relationship between classification of ‘art films’ and sex films has a detailed history,11 and Metzger’s pictures took advantage of the slippages, misrecognitions and overlaps between the grind-house and the art-house to maximise audience attendance. In the early 1960s, for example, the debate over the classification of films as ‘adult’ or designated for ‘adults only’ met with consternation from conservatives such as Martin Quigley, the editor of the Motion Picture Herald,12 and with exasperation on the part of art-house proprietors such as Walter Reade.13 This was because ‘adult films’ included films that ranged from foreign imports, mature family melodramas produced by Hollywood, underground and avant-garde work and sexploitation fare. Metzger’s films intervened to re-inscribe the battle over adult sexuality and its fantasmatic dangers along the lines of taste cultures and edified publics.

By positing a classed hierarchy between his own features and the sexploitation market, Metzger’s films made a claim for the ‘average’ audience and purportedly deflected the more ‘prurient’ viewer who was out to see flesh regardless of the finer points of story, sentiment and ambience. Metzger preferred not to term his pictures ‘exploitation films’ but rather ‘class speciality films’,14 or ‘class sex’, and tried to ‘appeal to the sophisticated filmgoer, not to the skinflick audience… he conceived of his audience as consisting of “sophisticated married couples in the mid-30s” rather than of ageing insurance salesmen with their finger poised behind their suitcases.’15 These intentional modes of address to a particularly classed audience produced a speculative, if not successful, alibi of a middlebrow spectator who wants, presumably, to be educated and edified more than entertained or aroused.

It is evident that Metzger’s film work engaged with and produced a unique discourse of taste around the consumption of sexual images. Looking at the historical reception contexts and the directorial and marketing strategies of Metzger, I want to ask how sexuality and sexual taste gets classed in the films he both directed and re-directed, through distribution, for an American audience. What are the specific aesthetic and ideological strategies deployed to create this art-erotica/soft-core hybrid, and what are its characteristics and effects? As Mark Jancovich notes:

[T]he study of pornography… requires us to acknowledge that sexual tastes are not just gendered but also classed and that, as Bourdieu argues in relation to the aesthetic disposition more generally, sexual tastes are not only amongst the most ‘classifying’ of social differences, but also have ‘the privilege of appearing the most natural’.16

The rhetoric of taste is deployed in Metzger’s 1960s films on numerous levels, on the level of aesthetics, decor, sexual content and performance, and in the films’ marketing and distribution.

‘MIDDLEBROW PORNOGRAPHY’ AND SEXUAL TASTES

Agnes: I like you because you’re always… ready.

The Alley Cats

The historical and aesthetic complication of Metzger’s output, which in the 1970s expanded from soft-core into hard-core pornographic product, is an interesting test case for understanding the economically destabilised film market of the 1960s. It also clarifies the debates over obscenity, classification, taste and aesthetic judgement that gained prominence at the time. 1968 saw the emergence of the CARA ratings system and the final sloughing off of the spectre of the arcane and obsolete Production Code Administration, which had regulated the visibility of licentious subject matter in Hollywood films since the early 1930s.17

Margot Hentoff, writing in 1969, pointed to one element of the saturation of the marketplace with sexual imagery:

There is almost no one left in town who is not an expert on sex, going from film to theatre to newsstand to bookstore – talking and writing about what he has seen. Everyone knows which theatrical coupling was real and which was simulated. Everyone tells us how sexually healthy he is and how non-erotic the performance, the performer, the book. The New York Review of Sex advertises in these pages. Screw and Pleasure, two of the other raunchy commercial offshoots of the old love-drug-revolution press, are read for fun by people I know. One turns the pages of these papers, sees a naked girl whose legs are spread, and says very Yellow Book – ‘What bad teeth she has!’ We are apparently developing a new genre of middle-class pornography: one which stimulates no one at all.18

Hentoff’s ironic reading of the contemporary scene is concerned with the ways in which the seeming underground has lost its sense of transgression and taboo. In the hands of a middlebrow, middle-class audience for whom aesthetic distancing, just short of boredom, is the hermeneutic strategy tout court for reading sexual representations, sex is evacuated of its secret thrills. Her wit, in the final line, proclaims null and void the experience of sensual shocks and affective inscriptions on the viewer’s body. This is an experience diluted and denigrated by the light of day and the codes of propriety, knowledge and taste that rule middlebrow consumption. No one can acknowledge their own arousal, a function of a border policing and regulated sexuality which distinguishes middle-class bodily response from the excesses of the lower-class lower body. In the context of over-stimulation, arousal is transformed into boredom.

In an attempt to make arousal ‘elegant’, Metzger’s films can be seen as part of this branch of a middle-class pornography, a niche market expanded to include less the maligned all male ‘raincoat brigade’ – envisioned as the true audience of sexploitation – but more the newly targeted ‘date crowd’. A reviewer, sceptical of their aesthetic innovation, commented that:

Metzger’s films allow middle-class people who have been conditioned to abhor pornography but who secretly crave it, to indulge their erotic fantasies with the firm conviction that what they are witnessing on screen is somehow more ‘serious’, more ‘uplifting’, than the crudely made quickies designed for the proles.19

Contrary to the work of Meyer, his competitor at the time, to whom Metzger was often compared, Metzger’s films refuted the more overt appeal to the low cultural sensibilities of the ‘cold-beer and grease-burger gang’.20 Whereas Meyer revelled in the inept physicality of his spectator and the boorishness of a stereotypical underclass, Metzger promoted an aspirational project, both in terms of genre and narrative, classing his films in terms of the already available and upper-middlebrow tenets of the art-house patron.

As Pierre Bourdieu notes, tastes manifest and justify themselves in the negation of the tastes of other groups, and are constituted as much through distaste and disgust as through a positive identification. As he writes:

[A]version to different lifestyles is perhaps one of the strongest barriers between the classes… the most intolerable thing for those who regard themselves as the possessors of legitimate culture is the sacrilegious reuniting of tastes which taste dictates shall be separated.21

Continually described in terms of his stylistic elegance, aristocracy, sophistication, distinction and refinement, Metzger remarked in an interview that:

We didn’t start out to be elegant. I was taught in college that the reason comedies are about rich people is because you shouldn’t have to worry about how they make a living… if you want people at leisure, they have to have resources.22

Lifestyle, particularly sexual lifestyle, defined by a utopian notion of sexual liberation becomes the landscape upon which Metzger unites the particularly apposite fields of youth culture and bourgeois living. Metzger’s films embraced the counter-cultural cache of the image of the ‘swinging sixties’ and sexual experimentation, of which his party scenes are the utmost apotheosis. These included images of women jumping fully clothed into swimming pools with men, a prison-themed bourgeois orgy replete with jail cell and a nightclub where a strip poker game leads to a female player’s removal of her underwear in full view of the club crowd. Yet Metzger managed to cloak such tactical screen debauchery in the patina of respectability, attempting to unravel sexual practice from its moralising and pathologising vestments. In Metzger’s films, narratives of erotic ennui and sexual existentialism piggyback on the fashionable pop-psychologised rhetoric of social malaise and youthful disinvestment. In The Lickerish Quartet, the disaffection of a family is disrupted by their pursuit of a circus performer, played by Silvana Venturelli, whom they are convinced starred in a stag film they have just screened. Her spectral appearance and disappearance spurs psychological rediscovery on the part of the father, mother and her son. In Therese and Isabelle, Therese (Essy Persson) returns to the site of her first love, a lesbian romance, at a now decaying and abandoned school for girls, in which her present experience of the space mixes fluidly with the recollection of her amorous entanglements with the elusive Isabelle (Anna Gael). The erotic listlessness of Metzger’s female protagonists is tinged with memory and melancholy – Marguerite Gautier (Danièle Gaubert), the relentless playgirl of Camille 2000, is haunted by her mysterious illness, which in deadly combination with her debauchery, prompts her demise at the end of the film. Monique (Reine Roman) wistfully pines for the icy Laurence, who we realise is actually Nadia, in the end of The Dirty Girls. And Leslie in The Alley Cats, on the heels of her rejection by her lovers and fiancé, considers suicide off the balcony of a church, only to be deterred by the lesbian artist Irena (Sabrina Koch).

FIGURE 5 Making pornography middle class in The Lickerish Quartet

These scenarios intermingle the prototypical gesture of refusal, sported by youth cultures with the literary pretensions of alienation and psychic torment. The literary sources of many of Metzger’s works – from Dumas to Merimee, from LeDuc to contemporary theatre – authorised the sexual liberties taken on screen. It also veiled them in the impulse of a modernised and utopic desire, a sensibility that necessitates a contemporary yet aloof viewpoint on the world and historical events. The preference for fantasy, chosen over the depredations of material necessity, gave Metzger’s films the structure of fables, erotic melodramas set against the eminent yet denied contexts of 1960s social change.

Metzger’s work therefore draws attention to the historicity of taste and its relation to sexual pleasure. If an understanding of taste is always reckoning with ways it can negotiate and train the body, in the Kantian project of distanciation, abstraction and aestheticisation, the location of eroticism in the act of consumption has no better model than sexploitation film and pornography. Russell Lynes, whose book The Tastemakers (1954) introduced the lexicon of ‘highbrow, lowbrow and middlebrow’ to the American public, reverts to gendered and sexualised analogies to lament the loss of pleasure in the pursuit of taste for taste’s sake within the post-war leisure economy. He writes, ‘a great many people enjoy having taste, but too few of them enjoy the things they have taste about. Or to put it another way, they are like a man that takes pleasure in his excellent taste in women but takes no pleasure at all in a woman.’23 This point, about abstraction of pleasure from its object, takes on another meaning in the context of 1960s public sexual culture. Sexual taste is coded into the structure of consumption, and it appears the most irrefutable of processes and preferences, aspiring to its own invisibility. Metzger’s films, as artefacts of a middlebrow trajectory, attempt to have it both ways, in taking pleasure in the aestheticisation and abstraction of sexual pleasure itself, in an erotic reflexivity.

STYLE, GESTURE, DÉCOR: CONSUMING SEX

Metzger’s films contributed to what Margot Hentoff identified as the inundation and overexposure of sexuality in the public sphere, coded in the same principles of access, but still embedded in the logic of the ‘tease’. As Thomas Waugh notes, ‘The tease, an erotic enunciation orchestrated like a tantalising power game, was still the characteristic erotic rhetoric of 60s public culture, the sexual revolution notwithstanding.’24 Metzger’s cinema is full of what would become generic soft-core aesthetic motifs which generated and refined the art of the tease in its narrative and mise-en-scène: focus on decorative objects such as sculptures, glass bottles, furniture and mirrors, and creative attention to off-screen space.

It is in the aesthetics and syntax of Metzger’s films that we can see the articulation of the paradox of art-house erotica. This is a place where the tease is held in tension between the edification and abstraction accorded to art and the materiality of arousal and an embodied spectator. Likening his films to the equivalent of foreplay, the representation of sexual acts and physical pleasure is met with the challenge of attempting to create a metaphor of pleasure into an aesthetic experience, between exhibition and concealment. These works move against the realist ontological function attributed to pornography as the limit of the representable. As Fredric Jameson claimed, ‘the visual is essentially pornographic, which is to say that it has its end in rapt, mindless, fascination.’25 However, Metzger’s images arrest the motion towards representational truthfulness of the sexed body in favour of presenting sex as aesthetically mediated or dematerialising. Many examples of this tendency can be seen in the texts, in which the mise-en-scène serves to make manifest a psychic function or process of desire, arousal and pleasure.

In certain films, actual physical objects within the set take on the role of lenses through which the sex act can be seen. In Carmen Baby, coloured glass bottles on a ledge become the telescoping filter to the imaging of sex between Carmen (Uta Levka) and her lover. The camera slowly pans along the length of their reclined bodies through the mediating tints and mildly distorted perspectives of the bottles’ organic contours. A similar device is used in Camille 2000 to serialise and fragment the sex between Marguerite and Armand Duval (Nino Castelnuovo) in her futuristic, all white, mirrored boudoir. Sex on a clear plastic bed is seen only reflected through the series of vertical mirrors which encircle Marguerite’s bed, as the camera pans across slowly and the image the viewer sees is broken up into a repetition of frames within the frame.

Representing the inner experience of primarily female sexual pleasure is also organised through this interface with the décor and decorative objects. In The Dirty Girls, Monique’s lesbian sexual longings are temporarily satisfied by a bout of masturbation with her own reflection in the mirror, in which her image is reduplicated in the frame and she appears to be kissing her own likeness. In The Alley Cats, Metzger frames Leslie’s face during an oral sex encounter with Christian (Harald Baerow) by a mirror against which she has her back. As she is being stimulated, a montage of shots of her point of view of the rococo ceiling and her bear rug which has been blindfolded are rapidly edited together. As Leslie nears orgasm, her head shaking back and forth in close-up, the ceiling, replete with curlicue details and gilt angels, begins to spin, alternating more rapidly with the bear’s head, and on cue with the non-diegetic sound of the film’s score and her moaning. Another heterosexual sex scene in The Alley Cats, between Logan (Charlie Hichman) and Agnes (Karin Field), uses a deliberate and distorted blurry focus, a mode of dematerialisation, to signify sexual pleasure. The physical gestures and facial responses of Agnes, astride Logan, appear fogged, as if the lens is smudged or out of focus, thereby cueing the spectator to the relationship between perceptual clarity and physical release, the parallel between the corporeality of sex and the recession of the image into a literalised ‘bodylessness.’ This performs an indexical move despite itself – attempting to allegorise and conflate the pleasure of sex with the impulse to watch, from outside oneself.

A comparable scene in Camille 2000 focuses exclusively on Marguerite’s face, in the background, and a vase of camellias, in the foreground. As Armand performs oral sex on her – implied off-screen – Marguerite’s moans punctuate an alternating focus of the camera, from her face to the camellias. The screen is split into two fields, as the flowers and Marguerite’s expression get fuzzy and then come into sharp view, in time with her accelerating orgasm. The temporality of pleasure is coded, through visual clarity and rhythm, to represent the unrepresentable female clitoral orgasm, cloaked in the excesses of a lavish mise-en-scène and the organic associations of the highly arranged flora.

These examples, a choice few among many, dramatise the trajectory towards abstraction which orient Metzger’s films to a discourse of taste. Attributable to Metzger’s signature style, it is style itself that is being eroticised. Such scenes are themselves easily abstractable from the films they are in. They emphasise the extent to which his films are ready-made for a cinephile sensibility, constructed of rhythmically adept fragments which operate, like the ambulatory and swerving route of fantasy, independently and often unmoored from their narrative content, capable of being re-arranged by the viewer.

Such is the guiding trope of The Lickerish Quartet, which depends on the misrecognitions of desire, as the metacinematic film screen, on which are screened stag films – thus becoming the mediating site for the operations of fantasy. The back of the screen, set up in the living room, becomes the physical and psychic space of traversal (by the camera and the viewer), mobilising the distance between a husband, his wife and his stepson through an erotic character who seems to emerge from the screen, from the stag film, to rearrange their fantasies and their memories. Metzger commented on the idea for the film:

FIGURE 6 The cluttered erotic frame: Camille 2000

It came from Dark Odyssey days. Whenever we screened the picture the film looked different for different audiences. I didn’t understand this, there’s nothing more permanent than film. Once its developed, it cannot change. And yet depending on the audiences, the film would actually change. The actor’s timing would change, the performances would change. Depending on who was in the theatre at the time.… And I wanted to kind of get that across, when we have a piece of film that is never the same, its different every time you run it.26

The mutability of the film image resembles the mutability and plasticity of sexual fantasy. Again we can see the importance of the cut, of the editorial signature, in Metzger’s films, as it allows for the camp reappropriation of images and scenes, gestures and dialogue, the standard of curation and the instrument of classification.

TASTE AND (SEXUAL) PREFERENCE

The camp value of Metzger’s films emerges from their flaunting of social change, and particularly female sexual liberation, as transformations in the consumption and economy of lifestyle. Taste, as Bourdieu reminds us, is emblematic of what one has and who one is in relation to the classifications of others and how one is classified by others.27 That a ‘modernised’ female sexuality became available for consumption by heterosexual men in the burgeoning sex industry of the 1960s is another commonplace of cultural history. We can see this hitoricist cliché transcribed into a scene in The Alley Cats, as Christian writes ‘GREAT!’ on Leslie’s naked back while she sleeps, assessing her previous night’s sexual performance and manifesting classification as body graffiti. The body becomes a vehicle, a prop like the décor itself, a material which requires evaluation, and through this evaluation it can be distanced from its physicality into style. It is also a mark of Christian’s appetite, an inscription of his own sexual taste, which has been sated by Leslie. The ‘GREAT!’ on Leslie’s back serves as an impetuous move signifying Christian’s defiant cad persona as well as a mode of address to the audience, a complicity to appreciate and consume Leslie, and the film itself, as a pure, fantasmatic surface.

The emergence and availability of particular sexual preferences – such as lesbianism and bisexuality – coded as consumer preferences, comes as a unique effect of the relationship between capitalism and sexual identities as they were mutually constituted in the 1960s. For Metzger, this offering up of alternative sexualities within his filmic narratives – from the lesbianism of Therese and Isabelle, The Alley Cats and The Dirty Girls, to the bisexuality exhibited in The Lickerish Quartet and Score, becomes the premise for an aesthetic ‘elevation’ rather than degradation of his films. Here, such images are filtered through his particular style and mise-en-scène. What Metzger’s films lack in comparison to his more ‘crude’ sexploitation competitors is an attribution or designation of pathology to its sexually and emotionally voracious characters.

In the 1960s, sexploitation films capitalised on lesbianism as a safe way to present sexual content without the incriminations associated with full frontal male nudity. Lesbian sex became a legal loophole, and as Kenneth Turan and Stephen Zito claim about sexploitation, ‘there is a great deal more explicit activity in the lesbian scenes than in the heterosexual ones, because it is much easier to fake sex between two women than between a woman and a man’.28 Despite the spurious assumptions in their analogy between sexual visibility and simulated sex, their logic makes clear how lesbian sexuality became a staple of adult film product, a token benchmark in the ‘progress’ of sexual liberalism.

Whereas gay male sexual cultures became accessible in part through the avant-garde film work of the New York underground, in the likes of Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith and Andy Warhol, images of lesbian sexuality had a more marginal existence as an accessory or indulgence of heterosexual male fantasy. Janet Staiger and others have credited the visibility of non-traditional sexuality in the avant-garde films of the early 1960s with opening up a space for the later flourishing of the soft-core and hard-core film market.29 Metzger’s popularity came on the heels of the waning of the New York underground in the mid- to late 1960s. Indeed, it is interesting to periodise the declining years of the underground, as well as the falling fortunes of the foreign film, in relation to the economic boom years of sexploitation, 1966–70.

Therese and Isabelle became the first sustained exploration of lesbian romance, adapted from Violette LeDuc’s 1964 memoir, La Bâtarde. One of the most ‘sensitive’ of Metzger’s portrayals and subsequently one which shows a minimum of bare flesh, Therese and Isabelle was a landmark film in its non-pathological portrait of lesbian sexuality. Couched within the art-house erotica mould, lesbianism became a consumable and aestheticised experience, heavy on sentiment, and sexual experimentation was positioned from a classed space of exploration and safety. Lesbianism was a stage passed through, a refutable yet pervasive melancholia haunting the now presumably straight and adult Therese. Literary voiceovers and the structure of memory which frames the narrative, in Therese’s adult return to the site of adolescent sex, buffer the impact of a film entirely devoted to lesbianism.

Lesbian relationships work in many of Metzger’s features, both his own and in the Audubon imports, as a structure of ‘diversification’ of the sexual commodity. Women, unmoored from traditional marriage and work, could be pictured in the extremity of their autonomy. In The Alley Cats, the artist and socialite Irena mediates between Leslie and her philandering fiancé Logan, ultimately through a seduction, delivering the emotionally harrowed Leslie back into her fiancé’s arms. And in The Dirty Girls, lesbianism, the surprise ending which reveals that the prostitute Monique’s affection rests with a woman, is more subtly mediated by an American john who has just had a sexual encounter with Monique. A shower scene in which the lesbian lovers are reunited is intercut with an image of the john reminiscing about Monique as he sits on the train, with a recurring male voiceover questioning, ‘Who is a dirty girl?’ The john becomes the authenticated spectator, the voyeur who haunts the unravelled ‘mystery’ of Monique’s inner life.

These films depict alternative sexualities as a refinement of sexual taste and a ‘sign of the times,’ as well as a gesture of pedagogy, in which sex is treated without guilt. Participating and forwarding the trend of ‘bisexual chic’ in his films, Metzger’s Score was one of the few films to present same-sex scenarios between both men and women. Indeed, the film’s male-male scenes caused a considerable stir in its initial release, as the straight male audience for sexploitation was considered too squeamish to sit through gay sex.30 Score’s status as a film which bridges the soft-core and hard-core stages of Metzger’s work is substantiated by the existence of both hard and soft versions of the film, as censorship and regional distribution necessitated different sells. As a result, a crucial five minutes of hard-core footage was pared down, excised or reinserted in a number of the prints of the film. Starring gay porn icon Cal Culver, Score featured a seduction of one married couple by another older, more experienced one, as husbands and wives pair up with each other in a play of erotic education, the learned initiating the naïve into sexual knowledge. Score’s innovation came at the waning days of the sexploitation genre, as hard-core pornography, enjoying widespread public exhibition, had begun to eclipse the now dated novelty of the soft-core sexploitation tease. Metzger went on to direct a number of highly popular hard-core porn features such as The Private Afternoons of Pamela Mann (1975), Barbara Broadcast (1977) and The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1975), and acceded to auteur status in the acquisition of his films by the Museum of Modern Art.

CONCLUSION

Having operated on the cusp of the underground and in pursuit of legitimacy and larger audiences, Metzger’s films of the 1960s represent an expansion of the sphere of acceptable consumption in a period of re-stratifying public taste. ‘Sexual liberation’ is allegorised through a Continental and fairytale elsewhere of lush homes and bodies pliable to the plasticity of fantasy. In assessing Metzger’s work in the present, one is struck by its capacity for camp reading as well as its auratic textures, as the diversions of the tease are redirected onto other surfaces – décor, objects, bodies. The soft-core predicament in the conditions of its production – the prohibition of the explicit sexual act – requires strategies of association to link it back to that act. The paradox between the aesthetic sensibility, for a person who has taste, or is looking for taste, is always contravened by the ways in which abstraction, in Metzger’s mise-en-scène, leads back to pleasure. The soft-core predicament is turned into an asset, as style becomes a mode of cultural capital, justifying sex while re-eroticising it through mediation, reflection and atmospherics.

If Metzger’s films ‘date’ in the present, they are coded as archives of the fluctuating American film industry, as the very hybridity which he pioneered is today a mark of its place within film history, addressed to an audience classed by their sexual tastes for ‘sophisticated’ erotica. By paying attention to the soft-core work of Metzger in the 1960s and early 1970s, we can begin to see how erotic films were legitimised and began to circulate amongst a wider audience, and what the impact of such a move up from the underground could and did yield within its own historical moment.