If it is real, I’d be a fool to admit it. If it isn’t real, I’d be a fool to admit it.

Allan Shackleton, about his film Snuff1

You could take the best expert today on moviemaking and he wouldn’t be able to tell if it’s real or not. The only thing is if you find the victim.

Israeli investigative journalist Yoram Svoray on snuff films2

THE SHOCK OF THE (UN)REAL

Without a doubt the most extreme form of underground cinema is the death film. Up to now, non-fictional footage of executions, assassinations and ritual sacrifice of the sort featured in the Mondo Cane and Faces of Death series have enjoyed a limited, cult following. Yet there are growing signs that this form is gaining more widespread public acceptance, and is emerging from the underground to appear in more mainstream forms of entertainment.

The principal reason why ‘real life’ death films have traditionally been an underground subgenre is because of the virtual ban on visual records of death, and especially violent death. As a result, the movies have found it not only necessary but profitable to adopt a variety of conventions for simulating loss of life. This was not always the case. In the early years of cinema, scenes of actual death were as likely to be encountered as their simulations. It was not President William McKinley’s 1901 assassination, after all, that Thomas Edison’s studio re-enacted on film, but a recording of the actual execution that same year of his killer, the anarchist Leon Czolgosz. With its depiction of the condemned man approaching the electric chair, being strapped down, blindfolded and finally electrocuted while staring directly into the camera, Edison’s Execution of Czolgosz with Panorama of Auburn Prison elicited a voyeuristic response in the viewer rather than surprise at a time when cinema was a ‘medium of shock and excitement and stimulation’.3 As such ‘spectacle films’ evolved from a documentary record of actual events into a form of fictional entertainment, simulations of violence increasingly became the norm while actual recordings of violent death tended to be marginalised, in effect going underground.

Although today executions have become a fairly routine occurrence in contemporary American society, they are sealed off from public view and are no longer the spectacles they once were, satisfying either the masses’ demand for justice or their appetite for violence. (The last legal public execution took place in the United States in 1937.) Now the public must turn to movies, television and video games for their dose of realistic – as opposed to real – violence. Such simulations thrive principally in the genre of horror cinema: first, in stylised and expressionistic monster films from Nosferatu (1922) to Frankenstein (1931), and later in increasingly realistic representations of serial killers and other outwardly normal sociopaths that are often based on actual individuals. Unable, and supposedly unwilling, to see the real thing, American spectators have turned to thrillers and horror movies for the next ‘best’ thing – realistic simulations of murderous violence that afford many the luxury of seeing and experiencing what they profess to abhor.

Recently it seemed that the real-life death of convicted Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh in June 2001 might become the most watched American execution in well over a half-century. Yet although McVeigh himself wanted his death broadcast nationally, the country’s first closed-circuit television broadcast of a federal death sentence was seen (besides by the actual witnesses in Terre Haute, Indiana) by an audience of only 232 survivors and family members of victims who gathered to watch the event at a secure site in Oklahoma City. And despite last-minute efforts of lawyers in an unrelated death penalty case to allow McVeigh’s execution to be videotaped in order to show that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, no visual document of the execution was made since federal regulations prohibit such recordings. As it turned out, witnesses of the death by lethal injection of the unrepentant McVeigh reported no evidence of pain or suffering on his part, and little satisfaction on theirs. ‘It was almost like the Devil was inside him looking at us,’ said one observer who had lost an uncle in the blast.4 Glaring up at the camera suspended from the ceiling at the moment of his death, McVeigh was both the star and the director of his own underground film. To the ‘grieving people’ watching him die he was ‘more [a] manipulator… than an offering to them.’5

The unsuccessful efforts by McVeigh to have his execution broadcast on national television, and by the attorneys who sought to have his execution videotaped, were essentially an attempt to bring back the practice of public execution in the age of electronic mass media. It was an attempt to show the real thing rather than a simulation. In effect, an underground genre of visual reality would have suddenly erupted into the mainstream of cinematic illusion, exposing the latter as such in the process. Even if such executions were made visible to mass audiences, however, this ultimate form of Reality TV is bound to be as contrived and artificial as any of the other so-called ‘reality shows’ that have saturated the air-waves in recent years (although this could change as such ratings-driven shows continue to ‘to push the envelope farther and farther in order to make them interesting… even if something terrible happens, even if someone gets killed’).6 As Wendy Lesser has foreseen, televised executions ‘would give us a false experience, a substitute experience, while leading us to imagine we had had a real one.… Watching on television as our government eliminated someone in a prison death chamber would seem like just another form of reality programming.’ The principal reason in Lesser’s view that such actual killings would seem so false is because, like most deaths on television (or, for that matter, in the movies), they are ‘almost always expected’. Lacking the element of surprise, a fully-anticipated event like McVeigh’s execution has virtually none of the shock value that could enable anti-death penalty advocates to argue that executions are a cruel and unusual punishment. Nor, for that matter, would live broadcasts of executions have the shock value we (paradoxically) look for in horror movies, and that we occasionally experience on live television when death is least expected, as in Lesser’s examples of Jack Ruby’s shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald or the Challenger space shuttle explosion.7

If we cannot find the shock of ‘reality’ in live broadcasts or videotapes of actual executions in which, even if they could be shown, the public display of inflicted death would strip it of its actual horror and neutralise it into a ‘false experience’, where then is such visual horror to be found? Once again, it seems, we must turn from underground visual records of actual deaths to commercial media fictions. By exploiting elements of suspense, surprise and spectacle, the fictional violence depicted on television and especially in the movies may elicit, as Lesser suggests, a greater sensation of horror in viewers than underground visual recordings of real-life violence.

Yet what if the sensational aesthetic elements of suspense, surprise and spectacle in mainstream fictional films were to be incorporated in episodes of real-life violence? Would this not produce the ultimate ‘horror effect’? It is not surprising, then, that a number of commercial filmmakers have adopted the strategy of incorporating what seems to be authentic death-film footage within their cinematic fictions. Steven Jay Schneider has noted this convention in films like Special Effects (1984), Mute Witness (1994) and Urban Legends: Final Cut (2000), which begin by first presenting some obviously fake ‘horror movie’ material and then switching to a supposedly real ‘snuff’ mode.8 Here I would like to pursue this observation, and to offer my own sampling of feature films that use this technique to push the envelope of what Cynthia Freeland calls ‘realist horror’.9 The films I have in mind attempt – either through apparently de-aestheticising techniques or though the opposite use of hyper-aestheticising strategies – to approach the theoretical limit of real horror through their references to, and occasionally their re-enactments of, actual filmed records of murder. Through their incorporation of amateurish, homemade snuff sequences, this subgenre of ultra-realist horror films reveals the concept of realist horror in underground as well as in mainstream fictional films to be a relative, aesthetic notion – at once an oxymoronic impossibility and a cinematic and cultural necessity.

USING SNUFF TO MAKE HORROR REAL

We may begin by briefly considering the film that has occasioned perhaps the most debate concerning the concept of realist horror: John McNaughton’s Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1990). This commercial movie, which has spawned its own cult following, is loosely based on the actual serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, but is more a fictional narrative than a documentary presentation. While various explanations have been offered as to why the film is so disturbing – because of its ‘attitude of neutrality toward Henry’,10 because Henry ‘defies external exegesis’ and ‘never comes to an ethical reckoning with his own savagery’11 – the movie is especially problematic because it presents murderous violence in a way that seems both real and staged. The most disconcerting and frequently discussed scene in this film is a sequence in which Henry (Michael Rooker) and his partner Otis (Tom Towles) view their slaughter of a suburban family that they have recorded on a stolen camcorder. In this sequence, which has been called ‘the scariest home-movie footage ever to make it to the big screen’,12 viewers see the killings not as they happen, but afterwards as we find ourselves watching the taped footage of the slaughter. As Freeland notes, what makes the camcorder sequence so disturbing beyond the brutality of its content is the viewers’ discovery that

we are watching this footage alongside the killers.… Point of view and real time are wrenched in a disconcerting way, with contradictory effects. On the one hand, the scene distances viewers and makes the murders seem less awful. The effect is as if we were just watching something on TV. The people in the family are already dead, depersonalized, not individuals. On the other hand, the amateur camera also makes the murders seem more real: things happen unexpectedly, everything seems unplanned and awkward. The view-point is not standard, and the murders are not cleanly centered for our observation.13

In Freeland’s view, it is the combination of our identification with the killers in the act of reviewing the video of their deed and the ‘grainy, tilted… amateur’ appearance of that home video that ‘makes the murders seem more real’. The viewer has the uncanny experience of watching a snuff film – a visual record of a murder filmed (and viewed) by the killer or his or her accomplices. (Small wonder, as David Kerekes and David Slater note, that in some edited versions of Henry, ‘an edit insert makes it clear much earlier on that Otis and Henry are watching a re-run of the murder on their television set. There seems to be some comfort in establishing that it is the two protagonists who were watching a snuff film and not us, the public.’)14 Only at the end of the snuff-film-within-the-film is it made clear that Henry and Otis are in fact the principal viewers. It is their emotionless, affektlos reaction to the video that provides such a stark contrast to what is presumably our horrified reaction at watching the identical footage. And the horror we experience is the result of the grainy realism of the snuff tape and the editing of the frame film, which bring about a temporary suspension of disbelief whereby we momentarily forget we are watching a fictional movie. For just a moment we think we are witnessing an actual snuff film: the horror we experience stems from our capacity – in contrast to Henry and Otis – to empathise with the terror of the apparently real victims.

Although it is certainly possible to consider ‘this snuff movie within a movie to be John McNaughton’s self-reflexive commentary on the lurid nature of his own movie’,15 the snuff sequence is first and foremost a means of giving a heightened sense of reality to the film as a whole. Yet for all its vaunted realism, the fictional snuff sequence in Henry hardly seems true to life if we compare it with footage of an actual sexually abused and terrorised victim in the hours and moments before she is killed. Even in the brief, heavily edited footage of Leonard Lake and Charles Ng’s treatment of their victims shown in the 2000 A&E documentary The California Killing Field, the inert, passive state of the actual bound women contrasts sharply with the thrashing and screaming of the fictional bound woman in McNaughton’s film. It would seem that claims about the realist horror of Henry are undercut by comparing the theatrical hysteria of the actress playing the part of the female victim in Henry and Otis’ video with the frozen terror of the actual victims in Lake and Ng’s tapes. As Irene Brunn of the San Francisco Police Department comments: ‘You hear about movies, and you read about books and sadistic things that some people do to others, but [when] you view it unexpectedly it is just a total shock – something I never want to see again.’16

THE REALITY OF SNUFF FILMS

Since 1975, attempts to reproduce purportedly non-fictional recordings of murder in fictional films have raised a host of intriguing legal, moral, social, but also aesthetic issues stemming from the fact that snuff films lead a paradoxical – indeed virtual – existence. These issues were first memorably raised by the snuff sequence tacked onto the unreleased 1971 Argentine movie Slaughter. The five-minute film-within-a-film purportedly shows a director filming an obviously staged scene in which a pregnant woman is killed. Aroused by the scene, the director proceeds to have sex on the set with a production assistant whom he ultimately (and seemingly actually) dismembers and disembowels while the cameras are still rolling. Released in 1975 with the title Snuff, the movie was marketed as – and apparently believed by many to be – an actual snuff film. The producer, Allan Shackleton, capitalised on rumours that such films were being made in and exported from South America, and that at least one such film had been made in the US; namely, a recording of the Tate/LaBianca murders supposedly filmed by Charles Manson and his ‘family’. Despite the inept result of tacking an apparently real snuff sequence onto a tacky exploitation film about a cult of young women following a Manson-like leader named Satan, Shackleton in effect bridged the gap between realist horror and real horror. He achieved this effect not only by resorting to a more graphic depiction of violence than that shown in Slaughter, but by deliberately staging this violence before the camera, thereby repositioning the viewer as filmmaker (as a surrogate for the director-turned-killer) and implicating the viewer in the violence.

The movie Snuff inaugurated a spate of underground cult films, and eventually several mainstream Hollywood products (for example: Hardcore (1979), 8MM (1999) and, most recently, John Herzfeld’s 15 Minutes (2001)), in which apparently real snuff recordings are incorporated into fictional films. As Julian Petley remarks, ‘the notion of the “snuff” movie was [soon] working its way into actual cinematic narratives, typically in the form of apparently “documentary” episodes inserted into the fictional story.’17 The technique of following an obviously staged murder with a snuff sequence is a way of making the snuff sequence seem all the more realistic. And even if, as Schneider has observed, everyone watching these films ‘knows that even the “real” murder is faked (fictional)’ – a phenomenon he calls the ‘aesthetic dilemma’ in snuff films18 – viewers of films like Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer may be led through a willful suspension of disbelief to be momentarily troubled and tantalised by the possibility that they are witnessing the visual record of an actual murder. Viewers can even become disoriented to the point that they can no longer be certain of ontological distinctions, and have the truly troubling sensation of what it is like to watch snuff despite their knowledge that what they are seeing is not – and indeed cannot be – real. Not only do fictional horror films in the tradition of Snuff incorporate staged snuff sequences to make themselves appear shockingly real, but these fictional films also give reality to snuff films. In making use of snuff sequences to arouse terror in viewers and to produce the horror effect, horror films and thrillers also play on people’s suspicions that an underground subculture exists in which snuff films are made and marketed.

It is one thing to note that the snuff sequences in most thrillers and horror films are not so graphic that viewers mistake them for the real thing. But the artificiality of these sequences, all of which can be traced back to the hokey history of the movie Snuff, has led skeptical critics to flatly deny the existence of such films, and to dismiss snuff as a modern myth. Thus Petley calls snuff movies ‘entirely mythical’, and repeatedly refers to ‘the stubborn absence of any real evidence’ of such films.19 The problem with such an assertion is that it fails to distinguish between snuff films per se and snuff ‘as a commercial commodity’, a concept that Kerekes and Slater (in a line cited by Petley) call ‘fascinating, but illogical.’20 While the existence of a commercial underground market in snuff films is open to question, there is no doubt that sexually sadistic killers do make visual records of their deeds. Besides the Charles Ng/Leonard Lake tapes I have already cited, there is the case of Melvin Henry Ignatow, who in 1988 forced his girlfriend Mary Ann Shore to photograph him sexually abusing and torturing his fiancée Brenda Schaefer, who died during the ordeal of chloroform inhalation. As former US Attorney Scott Cox described the more than 100 photographs that eventually were found: ‘They’re just gruesome. It’s like looking at a snuff film. At the beginning you can tell she’s mortified and she’s being ordered to disrobe and so forth. And then it depicts her being sexually assaulted.’21

Perhaps the most notorious recent murder case involving video recordings is that of the Canadian couple Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka. Technically the videotapes they made of their victims Leslie Mahaffy and Kristen French were not snuff films because, as in the photos of Schaefer’s ordeal, they only recorded the sexual abuse leading up to the girls’ deaths and not the killings themselves – and in the case of Mahaffy, her dismemberment. In this respect, the content of the real-life Bernardo tapes inverts the camcorder sequence in the fictional feature Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer: whereas the latter sequence shows Henry and Otis slaughtering a suburban family but breaks off when Otis begins to molest the corpse of his female victim, the Bernardo tapes depict his sexual degradation and violation of his victims, but breaks off before the actual killings. As might be expected, staged depictions of murderous violence are acceptable in mainstream movies while explicitly sexual scenes are taboo. (Sexual scenes are acceptable as long as it is clear that, like murder scenes, they are simulated and not real.) For a real-life sexual sadist like Bernardo, in contrast, the object is to preserve a visual record of sexual violence; recorded documentation of murderous violence remains taboo.

The absence of any visual record of the murders became a key issue in Bernardo’s 1995 trial, in which Bernardo and Homolka each accused the other of doing the actual killing. (Bernardo maintained that the murders of both Mahaffey and French were carried out by Homolka in his absence.) However, the prior death of Homolka’s younger sister Tammy Lyn appears to have been inadvertently recorded, since the anaesthetised girl expired at some point during her abuse. While it can be argued that this was not a snuff film because Tammy Lyn was unconscious during the filming, and because her death was accidental and not intentional, such technicalities only serve to point up the absurdities entailed in identifying and categorising snuff films: if the actual death of the victim must be shown and the victim must be conscious, then the various tapes made by Bernardo and Homolka meet only some of the requirements of the snuff film, and none of them satisfied all the requirements.

Far from supporting the view that snuff films do not exist because no one would be foolish enough to record evidence of the crime of murder (Kerekes and Slater, for example, claim that ‘sexuality aside, it is unlikely that… any figure… would allow themselves to be filmed committing the act of murder’),22 the Bernardo tapes lend credibility to the view that such films do exist. After all, the reason Mahaffy and French were killed in the first place was to eliminate them as witnesses of their own molestation; in effect they were killed to keep them from revealing what the tapes themselves revealed. (Indeed, after Tammy Lyn’s inadvertent death while she was unconscious, there was little to keep Bernardo and Homolka’s crimes from escalating to intentional killings of conscious victims.) So even if the tapes did not record the girls’ actual deaths, they recorded the sexual violence to which they were subjected that culminated in their deaths. Eventually the tapes were used as evidence that Bernardo had not only kidnapped and raped but also killed Leslie Mahaffy and Kristen French. In effect, the tapes recorded the reason – and indeed were themselves the reason – why the girls were killed.

We know in any case how important it is for the sadistic killer to keep a visual record of his sexual violence that may culminate in murder; indeed, this visual record is itself the reason why the victim must die. When the photographs that Mary Ann Shore admitted taking of Melvin Ignatow torturing Brenda Schaefer could not be found, FBI profiler Roy Hazelwood urged police to continue their search, claiming that Ignatow would not have destroyed them. ‘That was his record,’ Hazelwood maintained. ‘That was his trophy. That was the most important part of the entire crime that was still left to be examined.’23

If no one seems to have seen snuff films it is not because they do not exist, but either because they cannot be found or they cannot be shown. The only people who get to see snuff films (besides the people who make them) are law enforcement officers, prosecutors and the defendants’ lawyers. At Bernardo’s trial, the infamous sex tapes were strictly barred from the general public. Only 69 people, most of them prosecutors, were authorised to see them. When true-crime author Stephen Williams offered a detailed description of the taped scenes in his bestselling 1996 book Invisible Darkness, he was charged with two counts of disobeying the judge’s order restricting their viewing. Williams denied seeing the tapes, saying he had got almost all the details from material available to the public, but he refused to say where he had come by the rest – an offence for which he risked prosecution in Canada.24

While Williams managed to gain unauthorised access to the incriminating videotapes, the prosecutors who were authorised to see the tapes had at first been prevented from doing so because Bernardo’s attorney Kenneth D. Murray concealed them for 16 months. (During this time, Homolka cut a deal with the prosecutors and was charged only with manslaughter because she had agreed to testify against her former husband. Similarly, in Ignatow’s case the photographs which his girlfriend confessed she had taken of him torturing his fiancée were not found until after his acquittal. Unable to stand trial for murder under double indemnity laws, Ignatow could only be given a five-year sentence for perjury.) In 1997, professional misconduct complaints were issued against Murray, who was charged with becoming ‘the tool or dupe of his unscrupulous client’. In the case against him, the Ontario courts and the Law Society of Upper Canada had to decide whether to ‘interpret the videotapes as communications from Bernardo or, as one lawyer said, the crime itself’.25

Given the temptation on the part of defence lawyers to conceal graphic evidence of their clients’ crimes, and the tight security surrounding (and, at least in Canada, the heavy penalties awaiting authors and journalists who disclose) such evidence once it is seized by the police and impounded by the courts, it is no wonder that snuff films seem to some a purely mythic phenomenon. On the one hand, such films lead an elusive, phantom existence that cannot be verified; on the other hand, supposing that they do exist, they depict a reality so horrific that it cannot be shown except in cinematic simulations like those in Snuff and Henry. Snuff films present us with a paradoxical singularity in cinema: a glimpse of ultimate reality shorn of any and all special effects, and yet a subgenre whose own elusiveness makes it seem the stuff of myth – the ultimate special effect.

PASSING SNUFF OFF AS FICTION

The mythic status of snuff films has spurred underground and, increasingly, mainstream filmmakers to incorporate simulated snuff scenes in their movies, employing all manner of special effects – prostheses, camera angles, et cetera – to produce the illusion of reality. Sometimes, however, these movies about snuff films deal with the opposite problem: a character who produces a snuff film tries to find a way to exhibit and distribute it by making it seem fake. Thus in Larry Cohen’s Special Effects, film director Chris Neville (Eric Bogosian) inadvertently kills a girl on camera, and then decides to use the footage of the actual murder in a fictional feature that will appear ‘totally real’. In the course of the film, however, Neville switches from his original goal of making his movie ‘as real, as totally real as I can get it’, to ‘taking reality and making it look make-believe. That’s a special effect too.’26

An even more striking example of the same ploy to pass actual snuff films off as fake horror cinema is Doug Ulrich’s Screen Kill (1997), which concerns a goth-rock musician named Ralis who invites a horror film enthusiast named Doug to make a slasher movie with him. Doug soon discovers, however, that his partner Ralis is actually making snuff films, and that he, Doug, has been filming Ralis in the act of killing victims who also thought until the last moment that they were merely playing a role. Thus Ulrich exploits the familiar formula used in numerous other films such as F/X (1986), Body Double (1984), Mute Witness and The End of Violence (1997), in which a character in the business of making horror movies suddenly finds that he or she is involved in a real-life horror show.

As it turns out, Ralis is not content merely to make snuff films; he is determined to market them commercially, and has come up with a plan to do it. ‘I know a way of setting up a distributor,’ he tells Doug, who cannot believe he is serious and who worries that ‘We’ll have the fucking FBI all over us for making snuff movies!’ Ralis then calmly explains his plan:

You see, that’s the thing. We don’t put it out as a snuff movie. Snuff movies show one long take of someone getting killed, which makes it obvious that it’s the real thing. Now what we can do is we can insert different cut-aways with the actual kill, which will give the audience the illusion that they’re watching a very realistic special effect.

The snuff filmmaker Ralis simply plans to employ the opposite technique of realist horror films such as Screen Kill itself (which the actor playing Ralis, Al Darago, happens to co-direct). Whereas realist horror incorporates seemingly ‘documentary’ episodes of violence as (real) footage within the main (fictional) film, thereby adding authenticity to the fictional production, the real-horror filmmaker Ralis inserts fictional ‘cut-aways’ in the actual snuff sequence, thereby making the real murder scene seem fictional. After all, an obvious giveaway that a snuff film is not authentic are the cut-aways and the multiple camera set-ups and editing they entail. (As Petley points out, the murder sequence in the film Snuff seemed fake precisely because of the presence of such cut-aways: ‘the “murder” is filmed in classical “Hollywood” style, complete with alternating point-of-view shots and so on, which would have meant that the unfortunate “victim” would have had to have remained in place throughout the course of various camera set-ups!’)27 In contrast, it is precisely the absence of such cut-aways and ‘visual angles’ that makes a snuff sequence in a film look like it is documenting an actual murder. By inserting cut-aways into the sequence shots of his murders, the snuff filmmaker Ralis in Screen Kill simultaneously solves both the problem of how to make staged movie violence seem real, and the problem of how to make his snuff films available to a mass audience.

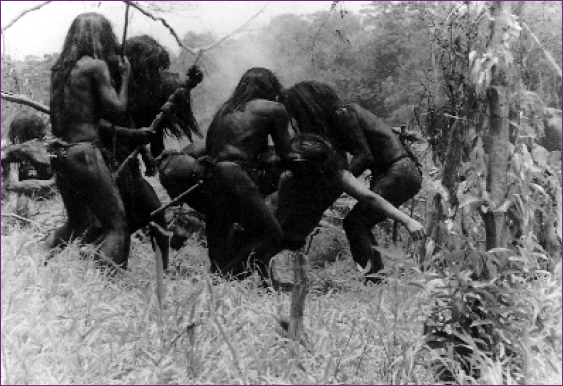

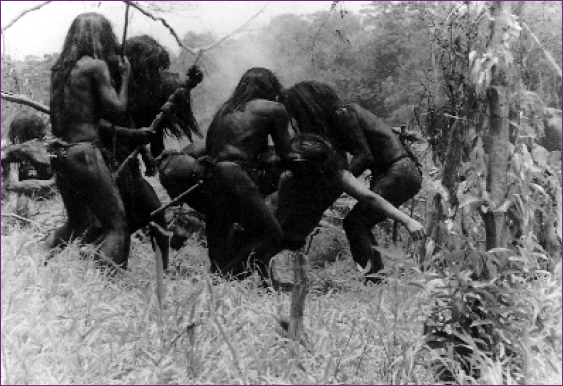

This crafty mixing of documentary and fictional footage to create an indeterminate, virtual murder scene is of course nothing new. Citing the ‘huge vogue’ of Gualtiero Jacopetti’s Mondo Cane series of documentary films in the 1960s, the British novelist J. G. Ballard has noted how they ‘cunningly mixed genuine film of atrocities, religious cults, and “Believe-it-or-not” examples of human oddity with carefully faked footage’. Yet, as Ballard points out, it is not just these cult shockumentaries that play havoc with reality and fiction, but the genre of the war newsreel, most of which ‘are faked to some extent, usually filmed on manoeuvres’.28 Nowhere is this confusion of the real and the fake more evident than in Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust (1979), in which actual newsreel footage of a military death squad at work is included as a film within the film. Far from reinforcing the distinction between fiction and reality, the inclusion of this archival material thoroughly blurs any such distinction because the fictional deaths in the film are presented as being more real than the documentary footage of actual killings, the latter of which are dismissed by characters within the film as ‘fake’.29 Yet while the effect of incorporating documentary footage in fictional films may be to subvert the distinction between fiction and reality, the purpose of this ploy is typically to make the fictional frame story seem more convincing and real, even if – as in Cannibal Holocaust – this means branding actual documentary footage as fake.

Once snuff films began making their way into commercial cinema, first as cult films and later as mainstream movies, a paradoxical situation arose. Audiences enter a theatre to see a horror movie or thriller with the express understanding that they will witness graphic spectacles and simulacra of death, but that real death itself can never be shown. But is this really so? Oliver Stone’s graphic use of the Zapruder film in JFK (1991) is, in fact, an instance of a type of snuff film being introduced – at once surreptitiously and flagrantly – into a mainstream Hollywood movie. Technically, of course, the Zapruder footage is not a snuff film because it was inadvertently filmed by a bystander at a public event who was not in any way involved in the murder. Yet its form is typical of snuff films. As described by Pasolini, it is the ‘most typical’ of sequence shots: ‘the spectator-cameraman… did not choose any visual angles; he simply filmed from where he was, framing what his eye saw – better than the lens.’30 Yet when Stone introduces the Zapruder footage as a film-within-his-film in the courtroom scene in JFK to give his movie added credibility, he does not present it simply as the straightforward documentary footage that it is. Instead, Stone works his own artistic fakery on the footage so that it begins to take on a unreal or surreal fictional quality of its own. ‘In Stone’s JFK’, as Ken Morrison observes,

the Kennedy head shot is lifted out of the Zapruder film and exploited by techniques of close-up, replay, and optical enhancements. Moreover, it is strategically held until the end of the courtroom scene to maximize its impact in an entertainment medium. In this way, frames 313 and 314 are placed within a Hollywood homicide technique.31

FIGURE 7 Fiction as death film: Cannibal Holocaust

Here we have the inverse effect as that in the underground cult film Snuff. Whereas the snuff sequence tacked on at the end of that film was a staged sequence that was made to seem real, Stone incorporates footage of an actual murder in his film in a way that makes it seem unreal and staged, much in the manner that Ralis presented his snuff films in Screen Kill or that Deodato introduced archival execution footage in Cannibal Holocaust. By adding cut-aways, close-ups and optical enhancements, Stone transforms Zapruder’s minimalist sequence shot into a polyvalent artifact in which any and all interpretations and conspiracy theories are equally tenable. Through its incorporation of Zapruder’s filmed record of a real murder, Stone’s JFK is actually more graphically violent and horrifyingly real than his 1994 film Natural Born Killers, despite all of the controversy sparked by the latter film’s simulated violence.

SNUFF AND SURVEILLANCE

It is worth noting, finally, how public space has changed altogether since 1963, particularly with respect to the deployment of surveillance cameras in most major public places. These days, when cameras are everywhere, an assassination attempt in broad daylight in an open public place like Dealey Plaza, Dallas (site of the Kennedy shooting) is likely to be documented by an array of cameras, both manned and unmanned. In fact, visual records of murder today are less likely to be made by the killer himself than by surveillance cameras that happen to record – and in some cases even incite – a violent act. Thus, in ‘techno-artist’ Natalie Jeremijenko’s piece ‘Suicide Box’ (1996), a motion-detection video system programmed to capture vertical motion was set up for a hundred days by the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. The camera ‘watched’ the structure constantly and recorded people leaping to their deaths, some of whom may have been impelled to jump by the presence of the camera. As justification for her apparatus, Jeremijenko claimed it generated ‘information about a tragic social phenomenon that is otherwise not seen’. Jeremijenko has since been working on a project called ‘Bang-Bang’, which she describes as ‘a set of low-power automated video camera triggered by ammunition fire. Whenever there’s an explosive event, it collects two seconds of video. They’re being deployed in places where one would anticipate ammunition activity: East Timor, Kosovo, L.A.’32 A case can be made that such automated documentaries that conflate art, snuff and surveillance represent one direction that underground films may be heading in the future.

In effect, there has been a new high-tech twist in the relation between snuff and surveillance since the 1970s and 1980s when, as Julian Petley has described, the British police’s quest for a ‘chimerical snuff film’ led them to launch a ‘surveillance campaign of horror and cult film enthusiasts, as well as individuals with sado-masochistic proclivities. In effect, the police ended up making the very films they were looking for.’33 With the proliferation of surveillance cameras today, from satellites in outer space, to stoplights at busy traffic intersections, to the motion- and sound-sensitive video-cameras of techno-artists, it is only to be expected that the authorities will once again create the very snuff films they claim to be looking for – a paranoiac possibility explored by Wim Wenders in his film The End of Violence.34 Even if filmmakers heed the call of critics to renounce fictional violence in their pictures, they will have little effect on reducing violent crime in real life. This is because the filmmakers who have the greatest interest in and closest relation to actual violence are not movie directors or producers, but the ‘undercover’ secret police and security agencies that have appropriated the most advanced film-recording technology for ‘security’/surveillance purposes. In a postmodern cyber-society like our own, the underground is no longer ‘under ground’, and ‘realist horror’ films are being superseded by visual records of real horror whose reality, however, may go entirely unrecognised.