UNDERGROUND/OVERGROUND: WAYS INTO WARHOL

The films of Andy Warhol are possibly some of the best known yet paradoxically the least viewed of underground movies. The bulk of the films remain largely unseen, rarely broadcast on television, and only the last three titles have been officially released on video. Only the most famous ones – notably My Hustler (1965), Chelsea Girls (1966) and Lonesome Cowboys (1968) – are exhibited at cinemas or galleries with anything approaching regularity.

Warhol’s career as a filmmaker has traditionally been divided into four stages by film historians such as Sheldon Renan and Richard Dyer.1 The first-period films, such as Kiss (1963), Sleep (1963), Haircut (1963), Eat (1963), Blow Job (1963), Couch (1964) and Empire (1964), were produced between 1963 and 1964. These films are characterised by the use of a singular long take, shot from a stationary camera angle, and their emphasis is on the celluloid’s plasticity as much as the subject matter presented.

Warhol’s second period, roughly running from 1964 to 1965, was produced largely with the assistance of Ronald Tavel (who would go on to form the Theater of the Ridiculous). These movies still use the fixed camera perspective but introduce sound as an element of the diegetic cinematic experience, with Tavel feeding lines to, or engaging with, the ‘cast’ from behind the camera. These films include Harlot (1964), Suicide (1965), Horse (1965) and The 14-Year-Old-Girl (aka Hedy, the Shoplifter, aka The Most Beautiful Women In The World, 1966). Warhol’s third period of filmmaking – from 1965 to 1966 – relies on quasi-vérité scenarios written by Chuck Wein, and includes Beauty #2 (1965) and My Hustler.

Both Renan and Dyer have suggested that Warhol’s fourth period is characterised by his use of expanded cinema, beginning with the double projection feature Chelsea Girls, which opened in New York in the Autumn of 1966. However, the first-period films were also screened in expanded cinema scenarios as early as January 1966, and such multiple projections formed part of Warhol’s ‘Up Tight’ events at the Cinematheque on 41st Street, several months before the shooting and cinematic release of Chelsea Girls (see below).

Further, given that the previous periods are defined by the collaborators involved, this distinction between the third- and forth-period films seems somewhat false. I would therefore suggest that Warhol’s last period of film production, for the sake of discussion, is better described as beginning in 1967 with films such as I, A Man (1967), Bike Boy (1967) and Lonesome Cowboys, and reaches its apex with cult films such as Heat (1972). In these films, the narrative emphasis gains greater importance.

Equally, this final period sees a more widespread focus on the concept of the superstar, the Factory’s own version of the Hollywood star system and a greater use of colour film stock. The last of these fourth-wave films were the most famous of Warhol’s output – Flesh (1968), Trash (1970) and Heat – and were produced in collaboration with Paul Morrissey, a protégé/collaborator who directed all three pictures (and who, it has been suggested, also directed most of the Warhol movies post-1967).2 These final few productions are better described as midnight movies than as underground films and Flesh, Trash and Heat have been released on video.

Identifying four broadly temporal stages within Warhol’s cinema represents an approach based purely on a move from avant-garde film through to a more immediately recognisable mode of narrative cinema. However, it would be just as viable to suggest that Warhol’s films also progressed through a series of stages based on the ways in which they were presented to an audience. Thus, while early productions were screened at the Factory or at underground cinema functions at venues such as the Filmmakers Co-op, some films were also presented in multiple screenings as a backdrop to the ‘Up Tight’ events. Here, screenings were merely one part of a larger affair that included pulsating music and performance/dance displays.

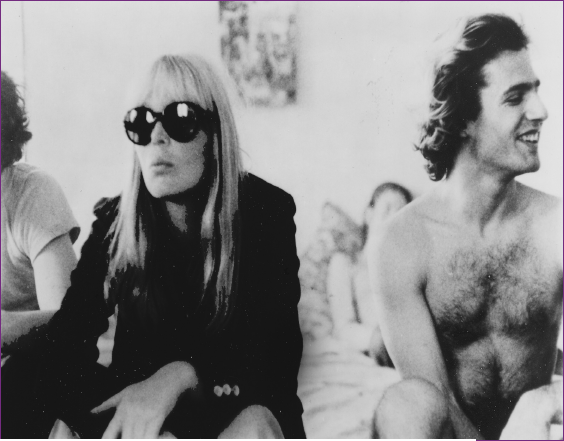

FIGURE 8 Trash goes respectable: Nico and Gerard Malanga in Chelsea Girls

Later films differed again merely because they were screened at more ‘respectable’ cinemas, beginning with Chelsea Girls, which, after a brief and very successful run downtown, moved to the midtown Cinema Rendezvous on West 57th Street. This move uptown garnered a New York Times review that condemned Warhol for screening his movies beyond the confines of Greenwich Village.

Warhol’s realisation that audiences wanted to see this work was the first clear step towards his making more commercially viable films and a move away from the supposedly difficult early movies. In POPism, Warhol acknowledges that by December of the following year, ‘We began to think mainly about ideas for feature-length movies that regular theatres would want to show.’3

IT IS ALL ABOUT IMAGE, ABOUT SURFACE, WATCHING

I guess I can’t put off talking about it any longer.

Okay, let’s get it over with. Wednesday. The biggest nightmare came true.… I’d been signing America books for an hour or so when this girl in line handed me hers to sign and then she did – did what she did. The Diary can write itself here.

[She pulled Andy’s wig off and threw it over the balcony to a male who ran out of the store with it…]4

For a few minutes, Warhol’s worst fear became actualised. Already the victim of exceptional and brutal violence, having been shot and nearly killed by SCUM manifesto author Valerie Solanis, Warhol was understandably upset. But this is not the fear of an assassination attempt; rather, in 1985, Warhol is upset that the surface has cracked. And, perhaps more than anything else, Warhol was interested in the creation and deconstruction of spectacle.

The Empire State Building is the supreme icon of New York City, of Deco architecture, of collective memories of cinematic experience; who can forget Kong’s final confrontation with the Air Force whilst hanging from the building’s spire? The Empire State Building was – as Warhol would later note – the first of his superstars:

Suddenly B said, ‘There’s your first Superstar.’

‘Who? Ingrid?’

‘The Empire State Building.’

We had just turned onto 34th Street.5

Possibly the most notorious of Warhol’s observation movies, Empire consists of eight hours of film of the Empire State Building – an icon of modernity celebrated as pure spectacle. This represents the cinematic equivalent to Warhol’s paintings and screen prints of tins of Campbell’s Soup or of Brillo Boxes. The commonplace rendered as art because of the way Warhol perceived it, reproduced it and demanded the viewer engage with it.

But if Empire was the most infamous of these films, it is only because it exists in the popular imagination as the supreme trial of patience. Like the excesses of modern art it becomes in the mind of the audience a conceptual joke – do you need to watch all of the film to have seen it, or is a casual five-minute section of Empire as good as viewing the whole movie? It should, of course, be noted that Warhol did not stand and film the whole movie; assistants and friends all supervised the shoot (including poet, writer, filmmaker, underground legend and independent film prothelyser Jonas Mekas). But this is only one aspect of pop iconography. Playing with our collected impressions of the totems of our culture, recognising them as signifiers for modern life, Empire is about the response of the audience as much as the icon itself. It raises the question of how we look at art and the world around us. Like the variations in the silk-screening process leading to fluctuations and nuances in colour and tone, each individual frame in Empire is slightly different in tone, in texture, as the light changes. One aspect of Warhol’s 1960s work is the recurring theme of repetition and non-identical repetition, that is, the repetition of the same thing only differently.

But Warhol was also concerned with people. The stars of his portraits (Elvis Presley, Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe, et cetera) found their echoes in the various personalities that made their way to Warhol’s studio. Thus, those who came to the silver-painted Factory would often be asked to sit for a screen test. Three minutes of 16mm film capturing the faces of everybody from personalities such as Lou Reed or Allen Ginsberg, through to the faces of young hustlers and aspiring models. Some of these tests were collated into groupings that became the basis for films such as The Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys (1964–65) and The Thirteen Most Beautiful Women (1964). The entire series is best known to contemporary audiences under the collective title Screen Tests (1964–66).

As for Andy, I wondered if he really liked people, or did he just like being fascinated by people?6

In these unremittingly sadistic films, individuals undergo the gruelling screen test ordeal in whatever way they choose. Almost inevitably the individuals try and look cool, but posing for three minutes invariably becomes impossible and the projected veneer of image begins to collapse almost immediately. In some cases the subjects begin to crack, smiling nervously and glancing from side to side, as if searching for help from behind the cold, unblinking eye of the Factory’s camera. Only the most self-assured individual can remain focused enough to carry off their image for the length of an unedited shoot.

Warhol’s fascination with spectacle is thus concerned not merely with the creation of the icon, manifested by the subjects of the screen tests as cool and composed, but also in the simultaneous deconstruction of the icon. When their image collapses and the person underneath emerges in minute flickers of anxiety, then the self-designed spectacle collapses and a new form of spectacle emerges. This is not the emergence of an essence, but a manifestation of immanence. Nothing is revealed; certainly any truth of the subject remains under erasure. The brief displays of nervousness – quickly hidden behind a new pose, or a drag on a cigarette (the ultimate cinematic signifier of cool) – enables the subject to re-immerse themselves in the spectacle, thereby allowing the viewer to catch a glimpse of the constructed nature of the spectacle of the public self.

The Warhol screen test must rank as one of the harshest initiation ceremonies yet devised. The subjects hope to appear suitable to join the Factory crowd and even Warhol’s inner clique. (Whether or not this clique actually existed is largely unimportant, those individuals filmed sitting in front of the clattering camera, be they queer street hustlers or wealthy uptown socialites, collectively believed that there was something unique in the Warhol entourage that should be aspired to.)

FIGURE 9 Cinematic sadism? The screen tests of Andy Warhol

Like a medieval inquisition, we proclaimed them tests of the soul and we rated everybody. A lot of people failed. We could all see they didn’t have any soul.… But what appealed most of all to us – the Factory devotees, a group I quickly became a part of – was the game, the cruelty of trapping the ego in a little 15-minute cage for scrutiny.… Of course, the person who loved watching these films the most – and did so over and over, while the rest of us ran to the other end of the Factory – was Warhol.7

Other films made by Warhol betray a similar scopophilia, in which the pleasure of looking at somebody’s emergent discomfort is equally apparent. Thus Screen Test #2 (1965) betrays a sadistic glee when actress Mario Montez, whilst being interviewed by Ronald Tavel, is harangued until she breaks down and reveals to her inquisitor that she is actually male. In his account of screening The 14-Year-Old-Girl in POPism, Warhol reveals a similar event: ‘When he [Montez] saw that I’d zoomed in and gotten a close-up of his arm with all the thick, dark masculine hair and veins showing, he got very upset and hurt.’8

While Mary Woronov’s autobiography recounts that her role in various Warhol movies – including what is probably his most famous work, Chelsea Girls – consisted of exorcising her demons, the director and writer encouraged her to give full vent to her dark side regardless of the effects. Indeed, if other members of the cast became agitated or upset then so much the better. Although to accuse Warhol of misogyny would be too simplistic and crass, it is nevertheless pertinent to observe that competition between the females in the film is brutal.

The Factory was like a court, the old court of King Louis or something like that – and people were always fawning after his favour, and at times he did toy with them. And one of the many ways that he’d toy with them is these girls would fight over whether they were going to be in a movie, or not in a movie, and whether they were a superstar or not, and whether they were sitting next to him or not. And the queens who also were there, would thrive on a bit of fighting amongst the girls.9

A girl always looked more beautiful and fragile when she was about to have a nervous breakdown.10

Warhol’s interest in cruelty and S&M may not have necessarily reflected his own personal tastes. These were merely aspects of his surroundings – both spatial and temporal – that fascinated him, just as he was fascinated with the drug and sex habits of those who entered his zone. However, the distance he enjoyed from the events around him suggests a certain coldness that in part must be seen as sadistic:

I still care about people but it would be so much easier not to care… it’s too hard to care… I don’t want to get too involved in other people’s lives… I don’t want to get too close… I don’t like to touch things… that’s why my work is so distant from myself.11

It was not for nothing that he was referred to as Drella – a fusion of Dracula and Cinderella – surreptitiously (and less so) by many amongst his amphetamine-fuelled entourage. He wanted to live vicariously through the experiences of those he filmed, people who performed their personalities and paraded their dysfunctions for his lens and ultimately for his voyeuristic pleasure.

SEX AND SILKSCREEN SUICIDES

Between 1962 and 1968 Warhol created a series of shocking silkscreen prints – ‘The Disaster Series’ – replete with images of gangsters, Bellevue Hospital, electric chairs, race riots, car crashes, suicides and newspaper headlines heralding numerous apocalyptic events. Even the artist’s most enduring image, that of Marilyn Monroe, must be seen as belonging to this series. She was, after all, the world’s most famous suicide, and it was this act that inspired the series of Monroe screen prints. These powerful images betray a fascination with various manifestations of violence: from the results of the grisly car crashes, through to the violence about to be realised in the brightly (electrically) coloured electric chairs.

These silkscreen prints reveal something that is both universal and forbidden: death. Death emerges in the images as both an actualised event (realised in the prints of a car crash or of a body plummeting from a building) and as an iconographical representation (for example, in a newspaper headline or a currently empty electric chair).

This engagement with the taboo, and with showing the forbidden, is also present within Warhol’s films of the same period. Most obviously it appears in his representations of all manifestations of sexuality and, to a lesser extent, drugs (see, for example, Couch, Blow Job, Chelsea Girls, My Hustler, Bike Boy). Warhol was obsessed with observing the chaos of the urban world around him. The excesses of his friends, associates and the numerous people who made the Factory their home, was a source of detached fascination for Warhol in the same way that society’s momentary excesses – manifested in events such as riots, violent death and stardom – were a source of interest. In this work, the forbidden and the hidden are exposed and dissected under the artist/filmmaker’s gaze, just as his earlier works (c. 1961–63) had engaged with an examination of the banal commonplace manifested through objects-as-icons such as the cans of Campbell’s soup or Coke bottles. But Warhol’s art – whether depicting images of consumerism, capitalism or execution – was never expressly political, the dissection neither offering, nor even so much as suggesting, an analysis of the mechanisms of power inherent within the electric chair or a drug deal or a sex act. Instead, the dissection is about fascination (be it Warhol’s, the media’s, society’s or, more commonly, all three) and the nature of the reproduced image itself.

I don’t really feel all these people with me every day at the Factory are just hanging around me, I’m more hanging around them.12

In Blow Job, one of Warhol’s earliest movies, a young man with a greasy quiff receives the infamous blow job for an estimated 45 minutes. Shot so that only the man’s head is visible, the oral sex occurs off-camera. The man leans back against a wall. The scratched celluloid is silent, nothing but projector hum. The young man, face in partial shadow, looks down. His head rolls back, presumably adjusting his pose so as to facilitate oral copulation. He looks down; again his head rolls back. At one point his mouth moves. The film burns to white. Next reel. Leader. More of the same. Head lolls. Eyes flutter. At the close of the film the protagonist lights a cigarette. End.

Warhol shot this 16mm film in 1963. According to POPism, the film was cast with ‘a good-looking kid who happened to be hanging around the factory that day.’13 He received a steady stream of blow jobs from the ‘five different boys [that] would come in and keep blowing him until he came.’14 Blow Job premiered in 1964 and was screened at various performances by the Velvet Underground. The film emphasises the act of oral copulation, but as the projected image focuses entirely on the head of the youth on the receiving end, the gender of those giving the blow job is concealed. Warhol’s statement that those giving head to the boy were male is irrelevant: to audiences watching the film, the youth could be blown by anybody. The point of the movie is to pay witness to the ecstasy on the man’s face – not to the image of his penis ejaculating.

The nature of Blow Job is ambiguous. Do we watch it as avant-garde text, documentary or underground art film? Repeated viewings suggest that Blow Job may be seen as a documentary, but rather than employing the traditional conventions of the documentary form the film is a liminal hymn. Like all of Warhol’s early productions, some members of the audience are forced to wonder if the film is an endurance test: should they watch the whole picture from beginning to end, or should they engage in another activity simultaneously and view it as something resembling moving wallpaper?

Blow Job works as a neo-documentary which follows the process of giving/receiving head through 45 minutes of sucking, and culminates (the audience is led to presume) in an off-screen ejaculation and (somewhat ironic) post-coital cigarette. Yet at the same time, Blow Job may be viewed as an anti-documentary, since the audience does not ‘learn’ anything. The audience is not given any specific information. (This raises the question, does that matter? Is that a function of documentaries anyway?) Instead they experience their own spectral appellation. Watching the flickering images of a blow job, should they be aroused? Appalled? Bored? Whilst the film functions as a voyeuristic glimpse of a sexual exchange, Warhol also emphasises surface, and engages literally with the texture of the celluloid – the scratches, the flickers and the play of shadow and light within the image are all crucially important to him. There is no editing because Warhol wants the audience to see everything – every inch of celluloid, every frame. The non-identical repetition of the projected image is what fascinates as much as the act that is transpiring on screen. This is a film about film as much as it is a film about oral sex or New York queer culture. Warhol wants the viewer to see the action but he also wants the viewer to engage with the medium as he or she is watching it.

Stylistically different from Blow Job is Warhol’s I, A Man, which was produced as a collaboration with the filmmaker Paul Morrissey. I, A Man – which takes its title from the erotic movie I, A Woman (1966), which was playing in New York at the same time the Warhol/Morrissey film was produced – locates its action in a series of encounters between a hustler-stud (Tom Baker) and six women (Ivy Nicholson, Ingrid Superstar, Valerie Solanis, Cynthia May, Bettina Coffin, Ultra Violet and Nico).

In I, A Man, the static camera and single-take shots that dictated the aesthetic of the early films is replaced by a greater variety of camera angles. (However, the film is still remarkably slow by contemporary standards, and the introduction of in-camera editing creates occasionally disjoined moments, loops of repetition and flashes of apparently random images.) Moreover, the silence that characterised Blow Job is replaced with a diegetic soundtrack. I, A Man is less film-as-art, film-as-installation or film-as-backdrop as it is simple, very loose narrative cinema. This is in direct contrast to Warhol’s previous films, which were engaged predominantly with the act of watching (even Chelsea Girls emphasised the experience of watching the double-projection images more than the experience of listening to the dialogue).

Like Blow Job, I, A Man retains an air of authenticity, as the audience can imagine the events in question actually transpiring. But while Blow Job records events as documentary evidence, as phenomenological experience played before the camera, I, A Man presents a series of sexual encounters with which the cast engage as a form of naturalistic melodrama. Each encounter is punctuated with a rambling conversation on topics that range from killing cockroaches to astrological symbols to lesbianism and so on. These conversations echo the rambling engagements presented in Warhol’s previous cinematic collaborations, but without the camp ferocity of Tavel’s dialogue or the dry irony of Wein’s scripts.

The ‘acting’ that occurs in the film is less about taking on a role than it is about putting specific people (Factory regulars, superstars, wannabe superstars) together and allowing their personalities to emerge and engage with one another. Like the earliest Warhol films, I, A Man also exists as phenomenological evidence, in this case of the meetings between the various individuals within the film. Where I, A Man differs from Warhol’s earlier works is in its emphasis on the star personas of the people involved rather than on the activities in which they engage. In earlier films the activity of stardom and the potential collapse of image (as in Screen Tests) was emphasised, whilst in I, A Man the star personas are maintained throughout.

Although more narrative than Blow Job, I, A Man still maintains a degree of engagement with the plasticity of film. In its editing, the cuts create momentary flashes of images, and the audio track cracks and spits like a sadist’s whip. These effects continually remind the audience that they are watching a film and so are engaged in a mutually complicit voyeuristic experience with the director and producer.

Throughout all of his movies, Warhol and his numerous collaborators attempted to engage with the notion of cinema from a uniquely personal perspective. One of Warhol’s main interests – most clearly envisioned in the earliest productions – is the act of voyeurism, in how an audience engages with the process of watching film. This interest is still apparent in his later works, the central difference being the way in which the audience is seduced via the process of narrative.

Like the Disaster series, films such as Blow Job and I, A Man, despite their stylistic differences, both seek to illuminate the ‘obscene’ and forbidden, framing that which society excludes despite the fact it is actually the everyday. Warhol is showing the audience something that is traditionally concealed because to see that which is hidden fascinates, and to see something completely, to succumb to a visual seduction, is ultimately what fascinates Warhol, and what seduces the audience of the Warholian cinema.