SEXING UP THE UNDERGROUND

Although exploitation film studies are only in their infancy, it has already become evident that historians and theorists have begun to identify certain resonances between low-culture sex and horror films and the work of the culturally accredited, cinematic avant-garde. Both exploitation and avant-garde cinemas are generally credited with an ability to shock, a concept now associated importantly with the cinema in its ‘primitive’ form – spectacular, non-narrative, focused around the body. Exploitation films would normally seem to shock audiences by recourse to the obscene – through the representation of things that are visible but which are usually proscribed from emerging into sight. The cinematic avant-garde, on the other hand, seems to shock audiences by manipulating visual experience itself, by playing with tolerances of vision in such a way that the act of seeing becomes a shockingly aberrant phenomenon. Both avant-garde and exploitation cinemas, therefore, comment equally upon the cultural organisation of visuality, on the spectator’s encoded experience of seeing.

It is not the general case, however, that the operation and effects of the avant-garde and exploitation cinemas are granted equal significance by most film scholars. The avant-garde cinema maintains a place within critical discourse far more privileged than that of the exploitation sub-genres. Exploitation films are, after all, widely held to be inarticulate and aesthetically regressive; authorless and derivative, they pander to the worst impulses in human nature – violence and unregulated sexuality. Avant-garde films, on the other hand, experiment consciously with the boundaries of experience, both personal and aesthetic; although often controversial, they strive for formal originality and deal with questions of widely recognised intellectual worth.

That said, most scholars would also agree that during the 1960s a certain number of attributions did begin to manifest themselves linking the cinematic ‘underground’ – the term used during the period to describe the filmic avant-garde – with the dominant strain of 1960s low-budget exploitation – the so-called ‘sex-exploitation’ genres. These links, in fact, were a subject of interest to numerous contemporary commentators:

A particularly curious aspect [of the recent, non-conventional cinema] has been the almost inevitable confusion between the Underground and the commercial, sex-oriented cinema. This confusion is compounded by the fact that most of the Underground newspapers in America carry advertisements for sexploitation sagas which are placed side by side with advertising displays for the works of Warhol… Kenneth Anger, etc.1

This ‘almost inevitable confusion’, however, apparently rested upon a basis more complex than media misalliance alone. There were structural, even thematic links between the two cinemas. As the same writer observes:

[Both sexploitation and avant-garde films] share the same insistence on portraying sexual activity and deviations; the same desire to abolish all censor control; they have in common low budgets, the use of amateur or semi-professional actors and a disdain or disregard for the gloss and polish of Hollywood film techniques.… Leaving aside the large proportion of Underground films which aren’t concerned with sex at all, it’s fair to say that the most commercially successful [underground] artists… have been those who featured sex prominently in their works.2

This essay will seek to examine in greater detail the relationship between certain elements of the intellectually accredited underground movement of the 1960s and the work of one ‘sexploitation’ auteur active during the same period. Doris Wishman’s cinema has been the subject of only limited critical analysis,3 but has in recent years gained a certain notoriety among aficionados of the abject, no-budget film world of the 1960s and 1970s.4 The director proved herself to be a by-product of the anomalous circumstances under which independent production was able to operate during these tumultuous decades. With at least 27 feature titles to her credit, Wishman is probably the most prolific American woman filmmaker of the sound era as well as a self-taught cinematic stylist whose work has been deemed by one critic ‘easier to recognise than Orson Welles’s’.5

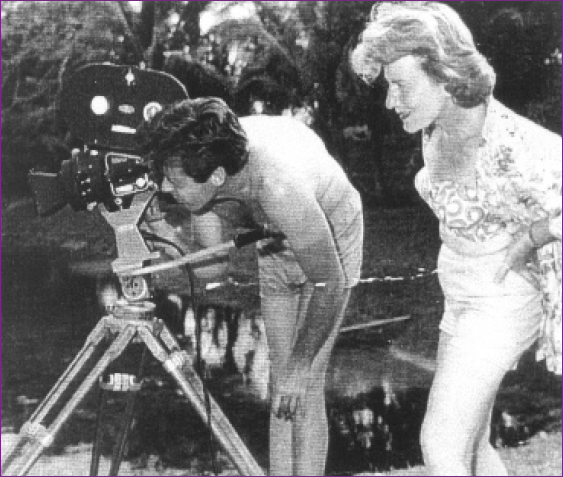

FIGURE 12 Doris Wishman working at Sunny Palms Lodge nudist camp with cameraman Raymond Phelan

Wishman’s definition exclusively as an exploitation filmmaker, however, is highly problematic. Her own stated commercial orientation, seeming adherence to recognised exploitation formulas and association with New York’s low-budget 9th Avenue film world seem to mark her efforts as those of an ‘exploiter’. Her marginalisation within this sphere (her films were among the least known and least successful in the exploitation genres), her explicitly recognisable and unconventional style as well as her recent recuperation within avant-garde retrospective/exhibition circles, however, indicate that Wishman has a certain role in the discourse on film art.

With only a modest background in film distribution and no formal training in production, Doris Wishman’s arrival as an independent filmmaker was actually the product of a confluence of forces that I intend to examine in more detail. Her knowledge of independent distribution gave Wishman a good sense for the idiosyncrasies of the ‘state’s-rights’ film market – a loose association of regional distributors who had lived in the shadow of studio-controlled distribution networks since the 1920s. Wishman’s lack of training in film production (almost impossible for a woman to acquire formally in this period) – dictated that she rely upon the technical support of various assistants. However, the dynamic industry for film and television production in New York during the early 1960s put her in an excellent position to access talent and services necessary to her efforts.6

Except for her reliance upon camera and editing personnel, however, Wishman tended to work with few collaborators, usually writing, producing, directing and overseeing the editing of her own films. It also seems significant that Wishman rarely attracted investors. Her first feature – Hideout in the Sun (1960) – was financed primarily by family loans, while subsequent financing originated substantially from distribution advances and Wishman’s own reinvested profits. In this way, Wishman managed to retain a high degree of control over her own filmmaking efforts.

It was typical of Wishman’s work, however, to correspond to the general outlines of certain recognised genres within the rapidly transforming sex-exploitation world of the 1960s and 1970s. Inspired by the legal and commercial success of Garden of Eden (1954) – a film that offered a fictional account of daily life in a Florida nudist camp – Wishman launched her production career in the colourful nudist genre. With the demise of the nudist market in the mid-1960s, however, she switched allegiance to the then-ascendant, black and white, sex and scandal genre known as the ‘roughie’. With the advent of ‘soft-core’ in the late 1960s, however, Wishman began a graduated manoeuvre to distance herself from the burgeoning ‘hard-core’ market and seek out an alternative filmic language.

In command of a system of production and assisted by her familiarity with outlets dedicated to marketing low-budget sex-exploitation features, Wishman had established herself by the early 1960s as one of the most active independent producer-directors working in the sex-exploitation milieu. Economically self-sufficient and dedicated to her craft, she claims to have cared little for the fact that she received no critical recognition for her efforts as a filmmaker. This may seem especially odd during a time when cinephile culture was rapidly proliferating and the discourse on ‘auteurism’ had been galvanised by both European and American ‘underground’ innovators.

Curiously, however, Wishman’s work did not go completely unnoticed by the film critical culture of the early 1960s. In a somewhat accidental review in the Summer 1962 issue of Vision, a columnist reported his response to a randomly-encountered double-bill featuring a dated Eva Gabor jungle romance (Love Island (1952)) and, at the top of the marquee, Wishman’s Hideout in the Sun.7

While the author goes on to critique in detail the tedious, ‘sexless’ quality of the nudist genre as a whole, it is noteworthy that his low esteem for the ‘salacious elements’ in Wishman’s work does not extend to the film’s plot. Defrocked of its dull but exploitable nudist trappings, he finds the film’s story, in fact, to be worthy of a backhanded compliment:

The plot of the first film – Hideout in the Sun – was so ludicrous that had it been intended for a ten-minute short it would have been one of the funniest, wildest ever.… Needless to say, the dramatic urgency… comes to a grinding halt once we hit the nudist colony.8

Describing the story in detail, the film concerns a pair of bank-robbing brothers hiding out from the police in a nearby nudist resort. One of the brothers – the bad one – falls to his death in a snake pit while running from the police. The other brother, having fallen in love with his nudist accomplice, decides to turn himself in to the law, planning to return to the peaceable nudist lifestyle once he has settled his debt with society. Padded out to seventy minutes with the addition of nudist exploitation footage – the trope of the genre itself – the film was reportedly ‘like slow death.’ But taken for its residual narrative, the above critic seems to see the basis for an engaging short film – ‘the funniest, wildest ever.’9

What is ‘so wild’ about Wishman’s nudist narratives is her inclination for genre mixing. Wishman’s nudist films appear to unfold on two levels. Firstly, there is the level of the nudist spectacle (the functional reason for the existence of the genre itself), while a separate level of narrative occupies a space in Wishman’s work entirely on its own. One has the impression of two films, one locked inside the other, unable to achieve mutual narrative resolution. In Hideout in the Sun, for instance, the trope of gangsters going on the lamb is subverted by their efforts to hide out inside a nudist resort. In Nude on the Moon (1960), the stereotype of the science fiction film is set at odds with the discovery of a colony of topless ‘moon dolls’ living on the lunar surface. Equally, in Diary of a Nudist (1961), a girl reporter goes undercover to write an exposé, not on urban political corruption but on nude sunbathing. Naked gangsters, topless aliens, a nudist Girl Friday – all invoke a stock of cinema clichés subverted by their reorientation within the larger context of the nudist film’s generic limitations.

For spectators versed in the mechanics of genre, such stark violations of generic boundaries cannot help but instigate a certain sense of absurdity. An important mode of avant-garde readership, the ironic resonance of Wishman’s nudist films aligns her efforts with the 1960s underground by providing an opportunity for transgressive reading. ‘It’s claimed that George Kuchar had a satiric purpose in making Colour Me Shameless,’ one 1960s critic notes facetiously, pointing out a similar tendency to mix genres within the work of one of the Underground’s most widely heralded operatives. ‘Most of the sex-and-deviation films are also amusing by… slightly sophisticated standards.’10 Films such as Wishman’s could be enjoyed for their moments of irremediable hybridity as well, therefore, as the tedious spectacle of celluloid flesh giving way to the lived experience of watching a film lost in the play of its own contradictions.

This effect of irony in Wishman’s cinema is complicated, however, by evidence that her transgressions were not intentionally ironic. Within Wishman’s film world, the juxtaposition of incongruous elements follows a logic only obvious to the filmmaker herself. Ironically, the real rationale that is driving Wishman’s system is the logic of genre alone. ‘I was really only interested in the stories,’ Wishman has frequently reported, ‘but if the public wants nudity, you’ve got to give them nudity.’11 Confronted by the opportunity to work within the confines of genre or not to work at all, Wishman chose the former. But the uncompromising manner in which she interpolated her narrative visions into the spectacle of nudist exploitation subverted genre once again. Wishman sees her nudist efforts, in fact, as dramas – not as comedies – wrapped within a commercially dictated shell. Similarly, the commentator above opines that Warhol’s ‘humor’ in films like My Hustler (1964) and Flesh (1968) also ‘seems accidental rather than intentional.’ ‘It becomes difficult,’ he argues, ‘to distinguish between the two.’12

AN ERUPTIVE MOBILITY

Wishman’s second critical period began in late 1964 with the release of her first film in what would come to be known as the ‘roughie’ genre. Distinguished by its lurid subject matter – particularly emphasising illicit and sado-masochistic sexuality – as well as by its stark, minimalist production values – black and white, hand-held cinematography and gritty urban settings – the roughie substituted a violent eroticism for the naive exhibitionism and colourful locations of the upbeat nudist romance.

With her switch to roughie aesthetics, Wishman also entered immediately into her most widely recognised period of stylistic innovation. Films such as Bad Girls Go to Hell (1965), My Brother’s Wife (1966) and Indecent Desires (1967) have attracted the attention of numerous cinephiles and counter-culture film fans able to rediscover such grind-house relics through the agency of home video. The irony implicit in this statement, of course, arises from the fact that Wishman’s films were technically never ‘discovered’ in the first place. Flashing invisibly across the marquees of fading downtown cinemas, bundled into salacious double-bills that no newspaper would dream of reviewing and for which many would not even accept advertising, Wishman’s contribution to the film art of the mid-1960s went entirely unnoticed. In the days before the advent of legal hard-core, the roughie was the equivalent of a bona fide dirty movie, and Wishman’s situation within the genre virtually guaranteed her continued anonymity.

Recent interest in Wishman’s roughie period, however, seems to have little to do with its sexual content – or lack thereof. Conforming to the conventions of the genre, her offerings tended to exhibit little nudity and less sex, rarely defying the still-lingering censorial standards of the mid-1960s. It may be, in fact, that this very absence of sexual content constitutes one of the cores of fascination with Wishman’s ‘rediscovered’ cinema. In an arguably post-porn universe in which public sexual expression has been linked – perhaps insidiously – with personal liberation, the reflex to repress the spectacle of sex seems to have become a form of pornography in its own right. Wishman’s roughies now appear as a nebulous meditation on our own assumptions about the effects of sexual freedom: before AIDS, before feminism, Wishman’s negation of the truth of sex haunts a world in which its absence now appears to have become a sort of deviant sexual thrill.

What seems to attract most viewers to Wishman’s mid-1960s film work, however, is its extraordinary mobilisation of stylistic signifiers, suggesting the operation of a unique and astonishing filmmaking intelligence. ‘Only Jean-Luc Godard can match her indifference to composition and framing,’ one of her early chroniclers notes with genuine admiration.13 The fact that a poorly funded filmmaker, working for explicitly commercial purposes, should have managed to create and replicate such a recognisable lexicon of surprising cinematic images constitutes one of the central attractions – and mysteries – of her work of this period.

Wishman’s style is perhaps best typified by a unique combination of eruptive mobility and unexpected stasis. The highly mobile hand-held camerawork common in her mid-1960s efforts traverses her mise-en-scène like an inexplicable presence, paradoxically constructing the camera operator as a virtual character in an otherwise fictionalised diegesis. Added to Wishman’s resiliently real locations – kitschly appointed 1960s interiors and cracked Manhattan sidewalks – and the spectacularly unrehearsed efforts of her semi-professional actors, Wishman’s work accumulates a veritable documentary sensibility. One feels that one is witnessing the actual recording of an actual event taking place in an actual space – the record of a film being made more than of a film itself. In this respect, there is a surprising ‘liveness’ to Wishman’s mid-1960s work, a sense of a world that cannot hide the traces of its origins in reality.

At the same time, however, one is struck by a deadly stillness that haunts Wishman’s output during this period. In spite of the immediacy of her method of registration, Wishman’s ‘cut-away’ editing style vivisects the most dynamic elements of her mise-en scène, draining the image of its tendency to represent real time and space. Her persistent reliance upon post-sync dialogue recording empties the diegesis of sonic density as well: voices – no matter what the location – seem to emanate from the profound depths of a soundproof booth. The impossible stiffness of her actors; her constant recourse to static inserts of shoes, ashtrays, knickknacks, wall hangings – anything inanimate; even her decision to use her own sparsely-furnished apartment as her principle location – all reinforce a sense that time itself has been frozen in Wishman’s world. This creation of a barren nowhere in which nothing happens and where there is an absence of continuous activity or motivation, begins to become one of her films’ most shocking and compelling attributes.

The overall effect of Wishman’s style, therefore, is a powerful sense that the integrity of reality has been wilfully and alarmingly deranged. Her films of the roughie period manifest a marked disrespect for the boundaries of the realism of her chosen medium and recording techniques, fragmenting and even falsifying the documentary element of her work through what begins to feel like an extraordinary act of narcissistic interference. In Wishman’s hands, the solidity of the shot is broken like match sticks; her style of montage treats the inviolable photographic image like a paper doll, imposing upon it the whim of some invisible hand. The visible sphere becomes captive to the almost sadistic manipulation of a narrative will, whose excessive exertions mark each cut as an irreparable scar, whose desires attempt to drain the image of any relationship with the world beyond that which it wishes to impose upon it.

As a result of these potent and vexing inclinations within her roughie work, Wishman has come to earn the interest of numerous later-day aesthetes, some of whom claim to see a relationship between her efforts in the exploitation demimonde and developments in various efforts associated with the avant-garde. Underground filmmaker Peggy Awesh – among the first to introduce Wishman’s work to a modern film-going public – has screened Bad Girls Go to Hell at the Whitney Museum alongside the work of Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet. Wishman’s appearance at the Harvard Film Archive in 1994 – her first public manifestation as an ‘auteur’ – was met with comparisons to Maya Deren and Chantal Ackerman. Screenings at the Andy Warhol Museum as well as numerous colleges and art theatres have also highlighted Wishman’s counter-cultural resonance.

Wishman’s penetration even into the music subculture ought not to be surprising. For instance, there is a notable affinity between her work and elements of the lingering punk underground – particularly in its feminist variants – within which the reputation of Wishman’s films as ‘sleazy’ and her authorship of numerous ‘bad girl’ characters have proven to have a durable appeal. Paradoxically, however, it is Wishman herself who most frequently refuses to admit that there is anything unwholesome about her films; nor does she claim to champion the parade of call girls, lesbians, and fallen women who populate her scenarios. Greatly at variance with nihilist punk aesthetics, the director has unswervingly insisted that her films were made with ‘love’ and is deeply offended when anyone refers to them as ‘trash’. She also insists that she is not a feminist and tends to stare blankly at cultural theorists who question her about her representation of gender. ‘People always talk about Wishman’s style,’ the stymied filmmaker has confessed, ‘but I just did what I had to do to get the film done.’14

Wishman’s oft-noted lack of comprehension for the appeal of her work within cinephile circles both comments upon and reduplicates the mystery surrounding her films themselves. A trash filmmaker who insists that her movies were not ‘trash’, and yet who also refuses to accept their designation as ‘art’, the problem of Wishman’s authorship becomes as complicated as her baffling stylistics. Few filmmakers welcomed into the circle of the underground elite do so without professing some kind of artistic mission; nor are such filmmakers generally spawned within the aggressively commercial context that gave birth to Doris Wishman. Yet, Wishman’s stock among the avant-garde continues to rise: she has recently followed John Waters and Alejandro Jodorowsky as recipient of The Chicago Underground Film Festival’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

THE ROUGHIE MYSTIQUE DECODED

As with her entry into filmmaking as a whole, the conditions under which Wishman’s distinctive mid-1960s stylistics came into being ought to be examined in more detail. Wishman’s situation as both a filmmaker and an auteur have much to do with the contexts within which ‘Doris Wishman’ came to be invented – not just as a repository of cinematic authorship, but also as a no-budget exploiter. In many respects, as a filmmaking entity Wishman does not really exist outside of certain processes of production and strategies of readership – a fact which, amazingly but refreshingly, she herself is usually the first to acknowledge.

The Doris Wishman of the mid-1960s first comes into being once again through the strictures of genre – namely, the roughie – a form which she freely confesses she elected to work in only after the collapse of the nudist market left her with no economically viable alternative. A poor-man’s neo-realism – part film noir and part stag film – the roughie took its cues from cheap erotic fiction and the social hygiene exploitation sagas of an earlier generation. It claimed to take harsh reality as its subject matter, bespeaking the dangers of urban life and the failure of traditional values.

The look of the roughies, however, conformed to the economics of independent filmmaking of the period. Black and white film stock – more affordable than colour – typified the production standards of most low-budget filmmaking enterprises through the 1960s, particularly in the neo-realist and avant-garde modes. The look of cinéma verité, the French New Wave and newsreel photography soon made black and white synonymous with the ‘realist’ agendas associated with these forms. Black and white was also increasingly associated with an ideology of authenticity once colour photographs began to become a dominant mode of mass representation.

Hand-held camerawork participated in the ideology of realism as well. Increasingly the mechanism for fast-paced, documentary reportage, hand-held cameras had found their niche in neo-realist cinemas by the late 1950s. This blurred the boundaries between feature production – long subservient to the ‘seamless’ industrial mode of Hollywood filmmaking – and the freeform look of home movies. The noticeable reference to the photographer embedded in hand-held camerawork also augmented the overall effect of authorial presence so important to the blossoming auteurist sensibility. Someone beyond the diegesis was clearly focusing, panning and recording the filmic event. The presence of the filmmaker, therefore, entered the diegetic universe as a reflection of technology.

Wishman’s oft-noted indifference to visual composition is a telling reflection upon the effects that such generic structures of registration had upon her work. The style of camerawork frequently attributed to Wishman’s name – ‘her singular camera technique’ as one critic puts it15 – generally had little to do with the director herself. As frequent Wishman cameraman, C. Davis Smith, has noted in an interview: ‘Doris didn’t get into how the scene was lit or how you should shoot it. She only wanted to know whether or not the action had been recorded.’ Hand-held shooting was quick, Smith claims, and ‘it worked well for that type of show.’16 Wishman herself has also commented that the choice of black and white was as much conventional as aesthetic: ‘It was just what people were using.’17 Wishman’s ‘singular… technique’ therefore had its origins in the pre-existence of a largely-encoded schema of registration which aligned her mid-1960s films both with the realist ideology of black and white and the heightened sense of authorial presence implied by mobile camerawork.

Within the realm of editing – admittedly Wishman’s favourite aspect of the filmmaking process – similar exigencies also need to be taken into account. Given the extremely limited budgets available to her, Wishman’s ability to record multiple takes, re-shoot problematic footage and assemble adequate ‘coverage’ for her films was often severely limited. Not an uncommon predicament among low-budget exploiters – often referred to as ‘one shot wonders’ – the hurdles she had to overcome in the editing process were continual and extreme. Missed cues, bad focus, disappearing props and unfilmed plot components frequently forced Wishman to develop new story elements at the editing table itself. Continuity problems invariably arose, forcing Wishman as editor to search for an available solution.

The solution to her problems, however, came in the form of a discovery she claims to have made early in her career – the cutaway. An old editor’s trick used to smooth over the transition between discontinuous shots, Wishman realised that the panacea to her editorial woes was a quick insert of some object situated within the vicinity of the scene’s main action. A tabletop, a picture on the wall, somebody’s feet, a quick ‘reaction shot’ of a person in the room – all could serve to cover a bit of bad dialogue or to smooth over the obvious elisions in a scene created at the editing bench. As elements within the diegesis, in Wishman’s estimation these extra-narrative glances did not disrupt narrative continuity but served instead to bandage the ruptures that confronted her during the editing process. The technique, however, has frequently been described as cubist in its effect.

Wishman’s noted ‘cutaway style’, therefore, had deep roots in economic necessity and in filmmaking tradition as well. In her eyes, the manipulation was little more than a corrective to the flaws endemic in her otherwise irregular registration process. In spite of the fact that avant-garde commentators often identify a stylistic effort in this highly visible element of Wishman’s work,18 the director herself acknowledges a major difference between the intentions of her own editorial efforts and the efforts of those who utilise similar techniques to achieve avant-garde ends. ‘There’s nothing worse than a jump cut,’19 she has pointed out, noting that the goal of all editing should be to maintain narrative continuity.

AN OBSCENE SPLENDOUR

It is in Wishman’s final period, however, that her affinity for and accessibility to avant-garde reading strategies seemed to reach its crisis point – its apotheoses, as well as its definitive rupture. Confronted by shifts in exploitation filmmaking toward increasingly explicit representations of sex and violence during the early 1970s, she faced a difficult choice. Should she continue to adapt to these changes and produce increasingly violent and sexually explicit work, or should she attempt to break with genre altogether and set out on her own?

Following the lead of the soft-core film market in the late 1960s, Wishman at first attempted to conform to the will of the new genre. Her first colour film after the roughie period, Love Toy (1968), signified a turn toward a more sexually central theme – a man gambles away a fortune, earning it back by offering the winner a night with his teenage daughter. It is also acknowledged that she worked on at least two hard-core films under pseudonyms during the mid-1970s as well – Satan Was a Lady (c. 1975) and Come with Me My Love (c. 1976). Dominated largely by scenes of sexual intercourse, neither Wishman’s narrative irony nor her stylistic inventiveness seemed able to rise to the challenge of subverting the generic spectacle of sexual pleasure.

Gradually abandoning the standardised codes of the hard-core genre, however, Wishman’s cinema of the 1970s came to be typified by a less explicit but actually somehow more obscene organisation of the somatic spectacle. The obscenity of Wishman’s 1970s efforts arises from its depiction of the body as a profoundly disruptive and disrupted phenomenon. Her work of the period posits a body out of control, tending toward collapse, representing the instability of somatic existence itself.

Transplanted penises that drive their hosts to murder, breasts impregnated with cameras and bombs, the agony of surgical gender reassignment. These strategies were ostensibly invented to reduce the need for stronger modes of sex and violence within her work. However, the admixture of murderous sex and sexualised dismemberment that typified Wishman’s work concocted a stronger, more vitally offensive play of taboos than that of her generic counterparts.

This obscenity is especially noticeable in the case of two Wishman features starring the striptease sensation Chesty Morgan. Deadly Weapons (1974) and Double Agent 73 (1974) are both premised upon the gimmick of Morgan’s monstrous 73-inch bust. In the first feature, Deadly Weapons, Morgan hunts down and smothers her lover’s killers with her enormous bosom. In the second film, she is a spy who uses a secret camera implanted in one of her breasts to photograph an underworld cartel. Exceptional in Wishman’s oeuvre for the attention the two films received from the press, Morgan was referred to by one critic as ‘a refugee from Freaks’, while another evaluated her pained performance as ‘more pathetic than if she were to have been posed in a side-show’.20

Besides Morgan’s sexual monstrosity, however, the central gimmick of her breast as a weapon exemplifies Wishman’s strange conflation of eroticism and violence within these films. In The Amazing Transplant (1970), a grafted penis becomes a kind of weapon as well, urging its formerly impotent recipient to rape and murder women. In Let Me Die a Woman (1978) – Wishman’s only foray into the ‘documentary’ field – violence and sexuality are monstrously joined in the testimony of actual transsexuals, who see their organic gender assignment as a form of disease. In one scene excised from currently available prints, Wishman features a distraught pre-op who is shown removing his own penis with a hammer and chisel. The film, however, does not shy from exhibiting the removal of a penis and scrotum in footage from an actual male-to-female sex change operation.

FIGURE 13 Chesty Morgan in Deadly Weapons

In addition to such sensational and disturbing subject matter, Wishman’s films of this period also evince a stunning aesthetic obscenity as well. Artless, incomprehensible, for many impossible to watch – not only the film’s content but the very filmmaking itself revolts aesthetic decency. Consider the agonies of Let Me Die a Woman, its ‘documentary’ integrity turned inside-out through the addition of staged soft-core sex scenes in which its authentic transsexual subjects perform simulated intercourse. Equally, the patent ugliness of The Amazing Transplant, whose return to colour intersects nauseatingly with the worst excesses of the 1970s palette. Then there is the inexplicable and sublime tackiness of Chesty Morgan’s wardrobe – reportedly her own clothes! – mixed with the impossible vision of her haggard grimace whenever her character is called upon to smile. ‘Atrociously directed and edited and invariably out of focus,’ one of the previous critics scolds dejectedly.21 ‘Deadly Weapons is an insult not only to those who view it, but also, perversely, to its uniquely endowed subject.’

It is painful to watch Wishman’s output from the 1970s. This pain reflected in the face of every female viewer who momentarily imagines herself burdened with Chesty’s stretch-marked endowments. This pain is also seen in the reaction of cinephiles as well. Her films of this period grate painfully against the colourful backdrop of her earlier nudist romances and the unexpected stylistic revelations of her classical roughie melodramas. Their discontinuities confound instead of astonish; their amateurism depresses instead of inspires; the only reward associated with watching them is the satisfaction of knowing that one has seen the last, the most wretched, the worst movie that has ever been made.

FIGURE 14 Conflating eroticism and violence in The Amazing Transplant

There is, therefore, an element of radical displeasure associated with watching Wishman’s films of the 1970s – a displeasure that, in some ways, pushes her efforts definitively into the realm of the avant-garde. Wishman’s aesthetic of obscenity goes beyond ‘trash’, beyond ‘camp’, beyond ‘low-tech’. It is a challenge to filmmaking itself. Her formal pornography works to de-fetishise the cinematic experience, exposing its cherished affectations as contrivances, ripping out the heart of its pleasurable illusions. It is not morality but vision itself that is shocked by Wishman’s excesses – the shock of the avant-garde. Before Wishman, one had never known that it was possible to produce such an obscene splendour.

Wishman’s romance with the filmic avant-garde, therefore, is fruitful but precarious for both parties. It is precarious for the avant-garde in the sense that in its appreciation of Wishman it might ultimately lose its faith in the cinema itself; precarious for Wishman in the sense that she might – much to the detriment of her vision – gain that faith which the avant-garde has lost. The marriage of avant-garde and exploitation remains an uneasy alliance. Film studies, however, can only profit by looking more frequently into the basement – and not just the ‘underground’ – of the filmmaking experience.