The Menace is loose again, the Hell’s Angels, the hundred-carat headline, running fast and loud on the early morning freeway, low in the saddle, nobody smiles, jamming crazy through traffic and ninety miles an hour down the centre stripe, missing by inches… like Genghis Khan on an iron horse, a monster steed with fiery anus, flat out through the eye of a beer can and up your daughter’s leg with no quarter asked and none given; show the squares some class, give ‘em a whiff of those kicks they’ll never know…

Hunter S. Thompson, Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs1

‘SHOW THE SQUARES SOME CLASS’: MASCULINITY, OTHERNESS AND REBELLION IN THE BIKER MOVIE

‘Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?’ asks a pretty college girl, an epitome of teen convention with prim dress and neatly coiffured hair. ‘What’ve ya got?’ growls back the leather-jacketed leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club, played as a study in taciturn brooding by a wickedly sexy Marlon Brando. Though brief, the snatch of dialogue is pivotal to The Wild One (1954), the film that paved the way for a slew of biker movies churned out by Hollywood throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. Loaded with defiant nihilism, Brando’s retort exemplifies the mood of renegade alienation and freewheeling machismo that pervades the film. It was this sense of undirected anger and unleashed passion that became central to the succession of movies based around the exploits of marauding motorcycle gangs – a genre whose combination of sexually charged menace and seditious nonconformity had special appeal to both the hucksters of exploitation cinema and to the underground auteurs of the art-house circuit.

The biker flick traded in many themes common to the wider genre of the road movie. The restless anomie of the celluloid biker, for instance, exemplified the ‘distinctly existential air’ identified by Timothy Corrigan as a defining quality of the road movie.2 Other traits Corrigan highlights as principal to the road genre were also evident in the archetypal biker film. For example, a sense of social destabilisation, with characters having little control over the course of events, was a recurring theme within the biker flick. Equally, the biker’s reverence for his ‘sickle’ was the quintessential expression of what Corrigan sees as the road movie protagonist’s spiritual investment in his vehicle – to the extent that the car or motorcycle ‘becomes the only promise of self in a culture of mechanical reproduction’.3 Most of all, the biker movie exemplified the masculine focus that Corrigan argues is central to the road movie, the genre promoting a male escapist fantasy in which masculinity is linked to technological power and the road is defined as a space free of the onerous shackles of domesticity.4 The biker flick also shared the ‘romantic alienation’ of the road genre, Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark arguing that the archetypal road movie ‘sets the liberation of the road against the oppression of hegemonic norms’.5 The narrative of rebellion integral to the biker genre also matched what Cohan and Hark interpret as the road movie’s capacity to explore the tensions and crises of particular historical moments.6 In juxtaposing the lawless marginality of the motorcycle gang against the conservatism of small-town America, the classic biker flick explored the shifting contours of contemporary cultural life, epitomising what David Laderman sees as the road movie’s characteristic positioning of conservative values and rebellious desires in an unsettling dialectic that encompasses both utopian fantasy and dystopic nightmare.7 But while the biker movie engaged with themes common to the road movie genre, the ‘chrome opera’ put a distinctive spin on the ‘road’ formula by giving exaggerated (and often grotesque) form to the road movie’s mythologies of masculine power and existential freedom.

FIGURE 15 The archetypal bike rebel: Marlon Brando in The Wild One

The daring independence and cocksure cool that pervade the iconography of the motorcycle represent an exceptionally phallocentric form of symbolic power. The sexual connotations to straddling the massive cylinder blocks of a Harley are unmistakable – an avatar of macho sexual power that the biker flick exploited to the full, extending and intensifying the road movie’s paean to masculine bravado. The figure of the ‘bad boy’ biker was also fundamental to the genre’s aura of virulent machismo. In its depiction of snarling, maverick outsiders, the biker movie conjured a form of masculinity predicated on aggressive individualism and difference. Based around the salacious exploits of ‘outlaw’ motorcycle gangs such as the Hell’s Angels, the lurid biker films of the late 1960s and early 1970s were especially notable for their themes of an uncontrolled, macho ‘otherness’. Primitive and barbarous, the outlaw biker was cast as existing beyond the margins of the ‘normal’, his unrestrained lusts and sneering disaffection setting him beyond the pale of mainstream culture.

Yet the biker movie’s treatment of these themes was avowedly ambivalent. In the biker genre the anarchic excesses of the motorcycle gang were constructed as a spectacle that was both appalling and beguiling, the biker flick mixing horror and fascination in equal measure. On one level the later biker films of the 1960s and 1970s presented the bestial depravity of outlaw motorcycle gangs as chilling evidence of a societal order in a state of collapse. But in other respects the biker movies themselves flouted mainstream tastes and conventions. Revelling in their anti-heroes’ wanton displays of savagery and violence, biker flicks themselves sought to ‘show the squares some class’ – their emphasis on transgressive difference effectively blurring the boundary between exploitation and experimental cinema.

‘A WHIFF OF THOSE KICKS THEY’LL NEVER KNOW’: WILD ONES, ANGER AND MOTORPSYCHOS

The biker movie’s origins lie in the teen exploitation films of the 1950s. Facing a decline in adult cinema audiences, Hollywood increasingly appealed to the lucrative youth market, the ‘teenpic’ industry coming of age in the 1950s with a glut of quickly made, low-budget features aimed at the young. Films such as Rock Around the Clock (1956) and Shake Rattle and Rock! (1956) capitalised on the rock ‘n’ roll boom, while Hot Rod Gang (1958) and Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow (1959) exploited the latest adolescent crazes. Juvenile delinquency was also a recurring theme, with a flood of ‘J.D. flicks’ – for example Untamed Youth (1957) and High School Confidential (1958) – which purported to sermonise against the ‘evils’ of juvenile crime, yet simultaneously provided young audiences with the vicarious thrills of delinquent rebellion.

Released in 1954, The Wild One was an early entry into the ‘J.D.’ film canon. The story of a motorcycle gang’s invasion of a sleepy rural town, the movie was loosely based on actual events. Returning from the stresses of war, many former servicemen struggled to settle back into the routines of civilian life. Some, searching for camaraderie and excitement, were drawn to the world of the motorcycle and fraternities of rootless bikers began to take shape. It was one such group whose weekend of drunken carousing in the Californian town of Hollister in 1947 became the basis for The Wild One. Fictionalised in ‘Cyclists’ Raid’, a short story by Frank Rooney published in Harper’s Magazine in 1951, the Hollister incident was taken to the big screen by director Laslo Benedek.

The film was produced for Columbia Pictures by Stanley Kramer, whose earlier success with Home of the Brave (1949) and High Noon (1952) had marked him out as a pillar of liberal morality at a time when the major studios were cowed by McCarthyite witch-hunts. However, while The Wild One’s narrative of conflict between a nomadic biker gang and conservative townsfolk had been originally conceived as an indictment of middle America’s greed and prejudice, this was an angle too radical for industry censors. Kramer’s intended ending had seen the town’s merchants refusing to press charges against the bikers because of the dollars the gang had pumped into their coffers, but this portrayal of capitalist hypocrisy was considered too contentious and was scrapped in favour of an enigmatic romantic pairing between gang leader Johnny (Brando) and archetypal goodgirl, Cathy (Mary Murphy). Nevertheless, while the liberal moralising of The Wild One was watered-down, the film’s portrayal of swaggering delinquents courted controversy and a mystique of alluring danger developed around both the film and the bikers it depicted.

In The Wild One Benedek and Kramer had sought to create an air of gritty authenticity. In pre-production, hours were spent interviewing Californian bikers, snatches of their conversation appearing verbatim in the movie as the filmmakers reproduced the lore and culture of maverick motorcycle gangs. To mainstream eyes the results often seemed outrageous. Harry Cohn, directorial head of Columbia, reputedly hated the picture and grudgingly released it only on the basis of the track records of Kramer and Brando. Others were equally hostile. Amid a wider climate of unease about the course of postwar cultural change, many national newspapers and magazines slammed the film as a celebration of anti-social delinquents. In Europe, too, The Wild One was a target for moral crusaders and in Britain the film was banned until the late 1960s through fear it would incite juvenile crime. But despite being abhorred by officialdom (indeed, partly because it was abhorred by officialdom) the movie was a hit with young cinemagoers – Brando and his bikers cheered on by audiences seduced by images of seditious cool.

The Wild One established many of the conventions that became the stock-in-trade of the biker movie – the simmering tension around the bike gang and their violation of social taboos; the provincial ‘squares’ terrorized by subcultural Others; the fascination with polished chrome, black leather, and other markers of menacing machismo; and the synthesis of moody introspection and crude belligerence that constructed the biker gang leader as an unthinking man’s Beat Poet. For most of the 1950s, however, major studios were wary of venturing into the territory of delinquent rebellion. In 1953 a Senate subcommittee had begun investigating the causes of juvenile crime and the following decade saw its hearings give special attention to the possible influence of the media. Amid the climate of hand-wringing and suspicion, therefore, the Hollywood majors were cautious in their treatment of wayward youth.

It was, though, a domain in which the majors’ lower-budget competitors felt at home. Leading the way were American-International Pictures (AIP). Founded in 1954 by James Nicholson and Samuel Arkoff, AIP specialised in courting the youth audience. The company built its reputation on films like Reform School Girl (1957) and I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) – movies that set autonomous and sexually aggressive teenagers against conformist and inhibited authority figures. In Motorcycle Gang (1957), AIP sought to reproduce the charisma of The Wild One. Its screenplay partially ripped-off from an earlier AIP exploitation flick (Dragstrip Girl (1957)), Motorcycle Gang’s narrative focused on the struggle between reformed delinquent Randy (Steve Terrell) and biker hothead Nick (John Ashey) for the affections of tomboyish sex-kitten Terry (Ann Nyland). However, filmed in bright sunshine and interspersed with slapstick and wisecracks, Motorcycle Gang was bereft of the noir-esque elements that gave The Wild One its edge, one critic reflecting that sitting through Motorcycle Gang was ‘seldom more disturbing than being stuck in the slow line at Disneyland.’8 The deviant biker gang put in a further (less desultory) appearance in another AIP release, Dragstrip Riot (1958), but it was experimental and independent filmmakers that best capitalised on the biker’s image of dark intensity and sexual danger.

Almost inevitably Kenneth Anger – occultist, perverse visionary, and premier figure of American avant-garde cinema – was drawn to the myths and rituals of the biker. Anger’s reputation as incendiary auteur was established early. While still only seventeen he had completed Fireworks (1947), an overtly homoerotic and sadomasochistic psychodrama which showcased his trademark hallucinogenic visual style. Relocating to Paris, Anger spent the next decade working on a variety of projects, including several short films and Hollywood Babylon, his notorious biography of Tinsel Town’s sordid underbelly. Returning to New York in 1963, Anger continued his exploration of the seamy eroticism repressed beneath the staid inhibitions of modern culture. Running across a motorcycle gang hanging out by the rollercoaster at Coney Island, Anger was inspired to make the film that won him recognition as America’s foremost independent filmmaker. Premiered at the Gramercy Arts Theatre in New York in October 1963, Scorpio Rising was later described by Anger as ‘a death mirror held up to American Culture’.9

Stylised and iconoclastic, Scorpio Rising makes explicit the edgy homoeroticism of biker culture, the film’s hyperbolic symbolism invoking the macho world of chrome and leather in a sardonic commentary on American mythologies of glamour, power, and masculinity. In an ‘Eisensteinian’ montage, Scorpio Rising intercuts visceral images of motorcycle subculture with a catalogue of media allusions, a jarring collision that climaxes with the blasphemous juxtaposing of Hitler and Christ. Throughout, the film’s sense of knowing irony is underpinned by its kitsch Top Forty soundtrack – Bobby Vinton crooning ‘Blue Velvet’ as a lithe stud buttons his bursting jeans and the Crystals bawling ‘He’s a Rebel’ as muscled bikers strike fetishistic poses in boots, buckles, and studded leather.

In Scorpio Rising the implied homoerotic charge of The Wild One becomes overt. Brimming with the semiotics of moral and sexual transgression, Scorpio Rising gives full play to the mythologies that formulate the biker as a symbol of unsettling Otherness. A similar iconography of violation and disruptive excess also figures in the work of another leading light of American underground cinema – Russ Meyer. And, again, the biker made an early appearance in Meyer’s oeuvre. A professional photographer turned independent filmmaker, Meyer had enjoyed moderate success in the late 1950s with tongue-in-cheek, soft-core sexploitation flicks such as The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959) and Eve and the Handyman (1959) before perfecting his distinctively boisterous and sardonic style in Lorna (1964), Mudhoney (1965), and Motorpsycho! (1965). In Motorpsycho! Meyer draws on media stereotypes of biker savagery to present a garish parody of mainstream culture’s voyeuristic fascination with illicit desire. An exercise in sleazy excess, the movie deals with the trail of rape and murder left by a trio of malevolent bikers, the gang ultimately self-destructing after being stalked by their vengeful victims. Again, then, the biker figures as a disconcerting challenge to ‘square’ taboos, though in Meyer’s hands the theme is given satirical inflection. Motorpsycho! is an exaggerated celebration of exploitation cinema, its larger-than-life clichés serving to lampoon the shrill anxieties and inhibited obsessions of middle America.

The sinister volatility of Scorpio Rising and Motorpsycho! contrasts starkly with AIP’s treatment of the biker mythology during the early 1960s. Beginning with Beach Party in 1963, AIP’s cycle of beach movies were a bubbly blend of music and comedy centred on a vivacious group of Californian teens. The surfside antics of adolescent funsters Frankie Avalon, Annette Funicello and co. were the focus for the Beach Party series, but a gang of bumbling bikers also made regular appearances. Led by the patently middle-aged Eric Von Zipper (comedian Harvey Lembeck mercilessly sending-up Brando’s smoldering angst), the ‘Rats and Mice’ biker gang of AIP’s beach movies existed as a comic foil to the surfers’ frothy hijinx. A jokey caricature of the 1950s wild ones, the inept Beach Party bikers were a motif for outdated rebellion – a symbol of generational revolt configured as laughably old-fashioned against the cheerful hedonism of the surf set.

The good-time exuberance of the Beach Party cycle was, as Gary Morris argues, part of AIP’s attempt to leave behind its schlock-horror origins in favour of films that could achieve wider commercial success.10 But the beach movies’ representation of sun-kissed, teenage fun can also be seen as constituent in broader shifts in the symbolic connotations of youth in American culture. Throughout the 1950s, notions of ‘youth’ had been surrounded by largely negative social meanings – fears of juvenile depravity serving as a vehicle for wider concerns in the face of rapid and disorienting socio-economic change. By the beginning of the 1960s, however, the intensity of the ‘J.D.’ panic was dissipating.

During the early 1960s a more positive set of youth stereotypes came to the fore, young people portrayed (celebrated even) as an excitingly new and uplifting social force. This was an iconography powerfully marshaled by John F. Kennedy in both his public persona and political rhetoric, youth coming to represent the confident optimism of America’s New Frontier. Commercial interests, AIP for instance, also figured in this upbeat ‘re-branding’ of youth. With the growing profitability of the youth market, consumer industries fêted young people as never before and ‘youth’ became enshrined as a signifier for a newly prosperous age of fun, freedom, and social harmony. This was a discourse embodied in the beach movies’ eulogy to ‘fun in the sun’ ebullience – an idealised teenage lifestyle in which the biker’s surly estrangement looked sadly anachronistic.

The ambience of national wellbeing, however, was transient. By the mid-1960s the American economy was stumbling, while liberal optimism crumbled in the face of racial violence, urban disorder and a spiraling sense of social discontent. Against this backdrop the beach movies’ innocent high spirits looked increasingly incongruous. But it was a mood of uncertainty that gave the biker flick a new lease of life.

A ‘STRANGE AND TERRIBLE SAGA’: THE HELL’S ANGELS, THE COUNTERCULTURE AND EXPOITATION CINEMA

During the mid-1960s the winged death’s-head emblem of the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club became synonymous with the murkiest fears of mainstream America. Amid the social turmoil of race riots, countercultral radicalism, and escalating opposition to the Vietnam War, a new wave of moral panics gave focus to broader anxieties – particular alarm surrounding the spectre of outlaw biker gangs. The Hell’s Angels, especially, were reviled as the heinous bête noir of civilised society. As in the 1950s, however, it was precisely this aura of fearful Otherness that guaranteed the biker subculture a special place in the hearts of both the artistic avant-garde and exploitation sleaze-merchants. Indeed, it was often difficult to tell the two camps apart; both scurrying to take advantage of ‘square’ society’s repulsed fascination for the Hell’s Angels.

The Angels had originally formed among California’s loose packs of renegade bikers during the late 1940s. In 1954 a merger with a San Francisco bike gang, the Market Street Commandos, swelled the Angels’ ranks and local divisions sprang up along the west coast. With the formation of the Oakland Chapter under the presidency of Ralph ‘Sonny’ Barger – a 6-foot, 170-pound warehouseman – the Hell’s Angels developed greater structure and organisation. Under Barger’s aegis the gang hammered out its own bylaws, codes of conduct, hierarchy, and insignia. Against this style of biker brotherhood, Brando’s leather-jacketed hoodlums looked almost quaint. By the 1960s the Hell’s Angels had taken the aesthetics of liminal dissent to new extremes – with long hair, Nazi motifs, crusty Levis, and customised motorcycles (‘chopped hogs’) whose low-slung frames, raked front forks, and cattle-horn handlebars were a symbolic expression of defiant nonconformity.

But the Hell’s Angels were still just one among a motley assortment of outlaw motorcycle gangs – for example, the Gypsy Jokers, the Commancheros, and Satan’s Slaves. In 1964, however, the Angels were plunged into the media spotlight. Following a biker party in the Oceanside town of Monterey, several Angels were arrested for the gang rape of two local teenagers. The charges were later dropped, but sensational newspaper headlines transformed the Hell’s Angels into America’s public enemy number one. A report hurriedly published by California’s Attorney General painted a lurid picture of outrages committed by assorted biker gangs, and throughout 1965 stories in the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, and Esquire highlighted the Hell’s Angels as the most deplorable of the bunch.

The Angels’ mounting notoriety made them the bane of conventional society, but within the developing counterculture they were eulogised as rebellious outsiders who refused to be pushed around by ‘The Man’. The truth was rather different. The outlaw biker culture of the 1960s exemplified reactionary chauvinism. Violent, racist, homophobic misogynists, the Hell’s Angels held the civil rights movement in contempt and brutally attacked anti-war activists. Nevertheless, many among the avant-garde cognoscenti revered the Hell’s Angel as a romantic ‘Noble Savage’, fondly imagining the outlaw biker as an icon of raw, spiritual freedom. Hence bikers were regular houseguests of psychedelic emissary Ken Kesey, while countercultural luminaries such as Allen Ginsberg and the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia struck up friendships with many Angels. Hunter S. Thompson also established his reputation as literary gunslinger through his account of the gang. Originally dispatched by The Nation magazine to write a story on the Angels, Thompson rode with them for a year as he researched Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gang – his 1966 bestseller, which further heightened the gang’s demonic mystique.

Countercultural luminaries were not alone in being captivated by the Hell’s Angels’ infamy. A Life magazine feature on the gang also caught the eye of Roger Corman, AIP’s exploitation-meister par excellence. Corman had directed an array of horror and western flicks for AIP and, sensing the potential of a film based around the exploits of outlaw bikers, rushed The Wild Angels into pre-production. Aiming for graphic realism, Corman and scriptwriter Charles Griffith undertook background research by drinking and hanging out with Californian bikers – and, for extra frisson, even hired several Hell’s Angels as film extras. Released in 1966, The Wild Angels established the template for the welter of biker movies that followed. As ‘Heavenly Blues’, Peter Fonda plays the leader of an unsavoury biker gang hunting down a stolen motorcycle. After a confrontation in Mexico, gang member ‘Loser’ (Bruce Dern) is fatally wounded and his fellow Angels resolve to return his body to his hometown – the film climaxing with an orgy of rape and destruction in the local church, the gang ultimately routed by the parochial townsfolk.

Billed as ‘the most terrifying film of our time’, The Wild Angels gave ambivalent treatment to the biker mythology. ‘The picture you are about to see will shock you, perhaps anger you!’ warned the movie’s precredits, but the ensuing flick was far from a straightforward denunciation of the Angels’ misdeeds. As Blues, Fonda cuts a quixotic figure. In a role that would become formulaic in biker movies, the gang leader is distanced from the violent extremes of his fellow Angels, but remains an uncontainable rebel. Blues is the biker constructed as romantic hero. Amid the violence and mayhem his key speech, with its demand for the Angels ‘To be free, to ride our machines without being hassled by The Man. And to get loaded,’ marks him out as a free spirit kicking back against the stifling conventions of the mainstream.

Here there are obvious parallels with the counterculture’s rose-tinted celebration of the outlaw biker. But Corman was no Allen Ginsberg. Where the counterculture had naively championed the Hell’s Angel as an icon of resistance to the establishment, exploitation filmmakers were more calculating in their caricature of his lore and lifestyle. Rather than putting the Angels on a pedestal, the biker flick took advantage of their shock value. In The Wild Angels and the films that followed, the Hell’s Angel was turned into an outlandish bogeyman – jarring the audience’s sensibilities, manipulating their obsessions, and laughing at their mores in a mischievous pageant of excess.

With a spartan plot and minimalist script (120 lines at most), the real centre of The Wild Angels is its salacious parade of transgression. Shots of open kissing between male gang members are calculated to offend conventional morals, while everyday norms dissolve in the portrayal of the Angels’ wild partying and constant brawling, their sexual violence, and invasion of small-town America (the bastion of conservative morality). Moreover, interspersed with the frequent sequences of ‘sickle action’ (backed by Davie Allen and the Arrows’ pulsating fuzz guitar soundtrack), the film privileges spectacle over narrative, action over intellect. This carnivalesque exhibition of the world-turned-upside-down was a theme common to AIP films during this period. As studio head Arkoff recalls, during the late 1960s outrage and misrule were the hallmarks of AIP’s audience appeal:

We started looking for our audience by removing the element of authority in our films. We saw the rebellion coming, but we couldn’t predict the extent of it so we made a rule: no parents, no church or authorities in our films.11

The relish for reckless thrills also featured in AIP’s psychedelic exploitation-vehicles – The Trip (1967), Psych-Out (1968), and Wild in the Streets (1968). But the ‘chopper opera’ was AIP’s finest hour. Shot in two weeks, The Wild Angels was panned by critics at the 1966 Venice Film Festival, but (like The Wild One a decade earlier) the movie was a massive hit with young audiences. AIP even had trouble keeping up with demand for prints of the film as it grossed $5 million in its opening month. The Hell’s Angels themselves, however, were not impressed. Feeling they had been misrepresented and short-changed by the film, the San Bernardino Angels sued AIP for $2 million, claiming (somewhat improbably) that the movie had defamed their good character. But the gang were soon placated with a $200,000 settlement, and Angels’ President ‘Sonny’ Barger even signed up to work on several of AIP’s biker sequels.

In all, AIP went on to produce around a dozen biker flicks. In 1967, while The Wild Angels was still screening, the studio quickly completed Devil’s Angels. Directed by Daniel Haller and starring John Cassavetes, this was another tale of small-town locals terrorised by depraved bikers. Again, the sparse script and storyline gave way to an emphasis on visuals, with panoramic shots of cruising motorcycles and a succession of ‘set pieces’ used to show off the gang’s lifestyle of beer-swilling, punch-ups, and rape. But it was US Films, an AIP rival, who produced the most successful biker movie of the year in Hell’s Angels on Wheels. Directed by exploitation veteran Richard Rush, the film starred Jack Nicholson as an introspective loner, Poet, whose spell on the road with outlaw bikers ends in a violent confrontation with the gang leader over the latter’s neglected and abused ‘old lady’. Here, the usual exaggerated coverage is given to the wild depravity of biker subculture, though with the added spice that the Hell’s Angels actually endorsed the film (the entire Oakland Chapter appearing in the opening sequence). Nicholson also appeared in a second biker flick that year, the actor assuming a more sadistic persona in Rebel Rousers, a lacklustre tale of biker mayhem completed in 1967 though not released until 1970.

Other independent producers also competed in the field. William Greffe came up with The Wild Rebels (1967), and Titus Moody released Outlaw Motorcycles (1967) and Hell’s Chosen Few (1968), while K. Gordan Murray offered Savages From Hell (aka Big Enough and Old Enough, 1968). But AIP were still leaders of the pack. Throughout the late 1960s biker films steadily rolled off the AIP production line, the studio often recycling props and using the same actors and crew from one movie to the next. In 1967 AIP followed Devil’s Angels with Born Losers, the first film to feature writer/director/actor Tom Laughlin in the role of half-Indian activist Billy Jack, who stands up against a predictably obnoxious biker gang.12 The same year also saw AIP release The Glory Stompers, with Dennis Hopper making his biker flick debut as the unhinged leader of the Black Souls Motorcycle Club. Subsequent years saw further AIP biker fare with the release of Angels From Hell (1968), The Savage Seven (1968), Hell’s Angels ’69 (1969, featuring cameos from ‘Sonny’ Barger and other Oakland Angels), The Cycle Savages (1969), and Hell’s Belles (aka Girl in the Leather Suit, 1969). Garish, low-budget exploitation movies, they were all true to the AIP formula, revelling in wild thrills and outrageous shocks. The next celluloid motorcycle epic, however, marked a revival of avant-garde models of the biker as bohemian rebel.

FIGURE 16 Bikers, counter-culture and transgression

‘LIKE GENGHIS KHAN ON AN IRON HORSE’: MYTHOLOGY, NATIONHOOD AND GENDER IN THE BIKER MOVIE

Easy Rider (1969) was very nearly an AIP production. The film that kicked the road movie genre into gear had been offered to Samuel Arkoff by the writer/producer/director team of Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, but the AIP studio boss demanded the right to impose his own director if production fell behind schedule. Instead, Fonda and Hopper took their brainchild to producers Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson who secured big league financial backing from Columbia. And from the outset the major studio ensured Easy Rider was distanced from AIP’s leather and chrome stable. Promotional strategies marked out Easy Rider as a more intellectual, highbrow affair – with the wistful tag-line ‘A man went looking for America. And couldn’t find it anywhere.’ Further underscoring Easy Rider’s artistic pretension was the film’s entry into the Cannes Film Festival, where it picked up an award for Best Film by a New Director.

Easy Rider is a landmark film, signalling the impact of exploitation and avant-garde filmmaking on the mindset and working practices of mainstream cinema. As Richard Martin argues, Easy Rider was a trailblazer of ‘the fusion of mainstream and art cinema filmmaking techniques in the nouvelle vague-influenced Hollywood renaissance cinema of the late sixties and early seventies’.13 The film’s innovative visual style, quick-paced editing, improvised dialogue, and fierce rock soundtrack gave it a sense of spontaneity and energy that resonated with audiences, Easy Rider grossing over $50 million on first release from a budget of $375,000. The movie’s ideological positioning also gave it cachet as a hip incarnation of the cultural moment. On the proceeds of a lucrative drugs deal the film’s protagonists, Wyatt (Fonda) and Billy (Hopper), leave California on a motorcycle odyssey through the American Southwest. Reaching New Orleans they drop acid with two prostitutes and freak out through the Mardi Gras celebrations, then return to the road – where they are gunned down by shotgun-wielding rednecks. The characters’ haphazard travelogue can be read as a cynical commentary on US society and politics. Beginning with the optimism of the open road and ending in the disillusionment of a shotgun blast, Easy Rider is an allegory for liberal America’s collapsing ideals as the US was traumatised by burning inner-city ghettos and the mire of the Vietnam War. ‘We blew it,’ reflects Wyatt in one of the film’s most poignant lines.

But Easy Rider is not simply a disconsolate critique of a society gone sour. As Barbara Klinger observes, rather than being ‘a clear-cut counter-cultural message about the state of the nation’, Easy Rider is a text of ‘conflicted historical and ideological identity.’14 Alongside the film’s images of countercultural rebellion, the ‘affirmative patriotisms of Americana’15 are also heavily referenced, connecting Easy Rider with many of the myths and ideals of dominant American culture – in particular the mythic figure of the pioneering frontiersman. Since the nineteenth century, dominant ideological discourse has configured the frontier experience as the crucible of American independence and democracy. Here, the frontier pioneer is constructed as a rugged individualist – sturdy, autonomous, and resourceful. A core theme in the imagery and narratives of the western, this mythology of individualism and freedom is also central to Easy Rider. Indeed, allusions to the western punctuate the film. The main characters’ names (Billy and Wyatt) are reminiscent of cowboy gunfighters, while Billy’s buckskin coat and Stetson are an obvious western touch. And, as Alistair Daniel observes, their journey across the vastness of the American landscape further invokes the pioneering spirit of the early settlers and the innumerable westerns that mythologise them.16 More widely, the whole biker movie genre can be read (at least in part) as a celebration of the ‘last American hero’, essentially a generic revision of the western. In fact AIP effectively retooled its western assembly line for biker films, with a wholesale shift of its western production crews and actors into the creation of ‘iron horse’ sagas. Moreover, many biker plots were actually lifted from classic westerns. For example, the narrative of Chrome and Hot Leather (1968) is indebted to the Magnificent Seven (1960), while Hell’s Belles (1969) borrows heavily from Winchester ‘73 (1950).

This immersion in western myth explains why the biker flick is a peculiarly American phenomenon. It also locates the genre within distinctly masculine themes and discourses. Like the subculture they depicted, the 1960s biker flicks invariably marginalised women, consigning them to the pillion seat as submissive ‘old ladies’ or sexually compliant ‘mamas’. More broadly, the biker genre shared the road movie’s decidedly masculine connotations of individualism, aggression, independence, and control. As Shari Roberts contends, both the classic western and road movie are genres ‘propelled by masculinity’, informed by ‘a residual, American, masculinist ideal’ which links masculine superiority with racial hierarchies, manifest destiny and closure’.17 Nevertheless, Roberts argues that this does not add up to a monolithic formula, the ‘more fluid’ character of the road movie offering potential space ‘for protagonists of any nationality, gender, sexual orientation, or race’.18 Hence the 1990s saw the road genre recodified – its masculine, heterosexual codes reconfigured by films such as Thelma and Louise (1991) and My Own Private Idaho (1991).

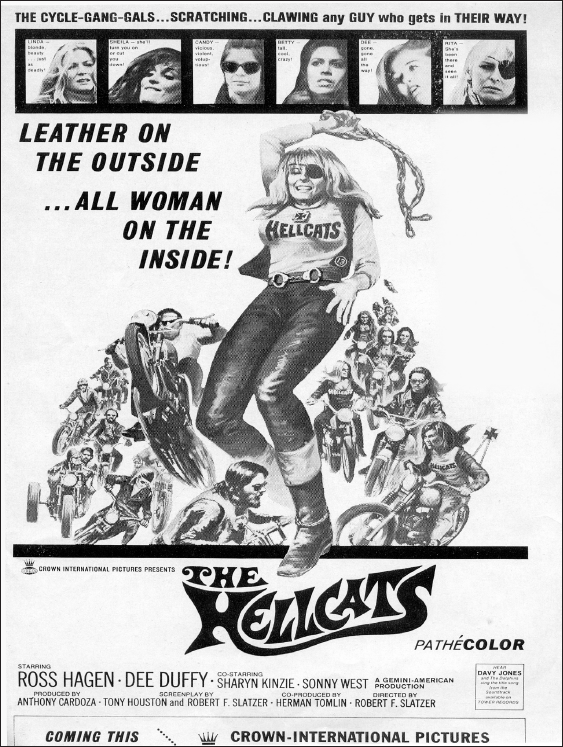

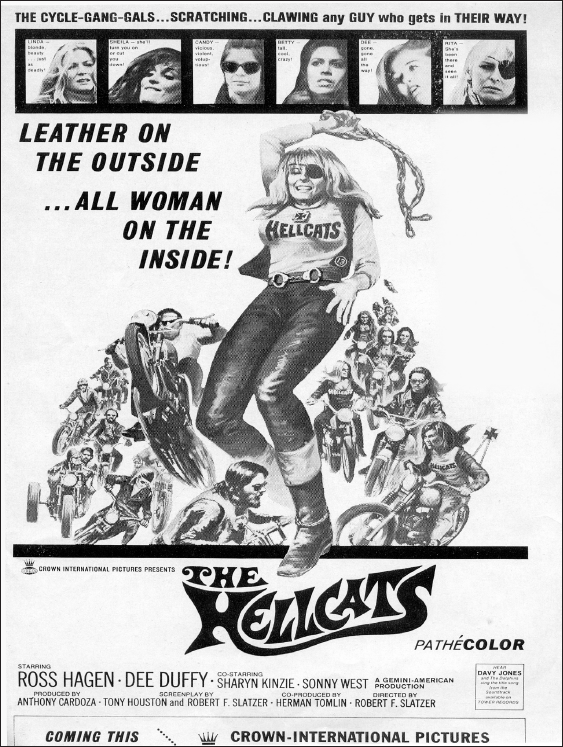

The biker flick was also ‘propelled by masculinity’. Indeed, the casual regularity with which biker films featured the rape and molestation of women marked them out as appallingly misogynistic. But, even here, there were spaces for recodification. Of course, there are many ‘motorcycle’ films that focus on women, these invariably oriented around an eroticised pairing of femininity with the phallic connotations of the powerful motorbike – from artsy erotica like The Girl on the Motorcycle (aka Naked Under Leather, 1968), to contemporary soft-core offerings such as Hollywood Biker Chicks (1998) or the more robust Butt-Banged Cycle Sluts (1995). Yet there also exists another, more transgressive, tradition in which the macho creed of the biker is inverted and women appear as dangerous and hard-hitting predators. AIP’s Mini Skirt Mob (1968), for instance, features a group of tough biker women, while The Hellcats (1968), Sisters in Leather (1969), and Angels’ Wild Women (1972) all focus on violent female bikers who terrorise those men who dare to cross their path.

The most incredible example of the subgenre, however, is She-Devils on Wheels (1968). Independently produced by Herschell Gordon Lewis (who had earlier crafted the shlock-horror classics Blood Feast (1963) and 2000 Maniacs (1964)), She-Devils on Wheels centers on ‘The Maneaters’ – a sadistic, all-girl biker gang who select their sexual playthings from a ‘stud line’, later dragging the discarded lover behind their speeding motorcycles.

None but the most delusional would try to redeem the likes of Angels’ Wild Women, The Hellcats, or She-Devils on Wheels as ‘feminist’ texts. Nevertheless, in their carnivalesque inversion it is possible to identify elements of disruption. Like the over-sized and domineering female characters distinctive of Russ Meyer’s films, the ‘She-Devils’ of the biker flick can be interpreted as ‘a revel in gendered excess’,19 an exercise in exaggerated caricature that sends up and usurps the conventions of respectable filmmaking. Indeed, this appetite for the grotesque and scorn for mainstream taboos is a trait central to the celluloid biker canon – and to exploitation cinema more generally. Ribald and bawdy, these are films that delight in tweaking the tail of conformist sensibilities through their love of all that is shocking, liminal, and ‘unacceptable’. As such, Easy Rider sits uneasily in the genre. Cerebral and reflective, Easy Rider is not really a biker flick at all. The classic biker movie rode roughshod over intellectual subtleties, the root of the genre’s appeal lying in its full throttle, blood-and-thunder sensationalism.

‘THE MENACE IS LOOSE AGAIN’: THE BIKER MOVIE’S LAST STAND

With the box-office success of Easy Rider more biker movies followed. Wild Wheels (1969) saw bikers battle a dune buggy gang, while Roger Corman returned to the saddle with Naked Angles (1969). Even to devoted fans, however, the genre was beginning to pale and producers looked for new spins on the formula to refuel their engines. Al Adamson (who earlier masterminded Angels’ Wild Women) came up with a biker/blaxploitation crossover in The Black Angels (1970). Director Lawrence Brown, meanwhile, proffered the even more unlikely concept of transvestite bikers in The Pink Angels (1971). The biker/horror hybrid also appeared with the release of Werewolves on Wheels (1971) and (from Britain) Psychomania (1971). Throughout the early 1970s the biker movie spluttered on, though releases became increasingly sporadic. Audience fatigue played a big part in the genre’s decline – the market could bare only so many two-wheel spectaculars. But other factors also contributed to the biker flick’s demise.

FIGURE 17 Phalic power: female bikers in The Hellcats

FIGURE 18 Contemporary biker imagery: Chopper Chicks in Zombietown

Jim Morton suggests that the popularity of biker movies declined after the true viciousness of the Hell’s Angels was exposed at Altamont in 1969.20 Hired as security for a Rolling Stones concert, the Angels proceeded to intimidate and beat both the audience and performers, stabbing to death black spectator Meredith Hunter in front of the stage as Mick Jagger nervously sang ‘Sympathy for the Devil’. After Altamont, Morton argues, the Hell’s Angels were ‘no longer funny symbols of rebellion’, but were revealed as being ‘really as dangerous as everyone said they were.’21 However, while events at Altamont certainly blew apart the counterculture’s veneration of the Hell’s Angels, the outrage was actually a gift for exploitation filmmakers. Their murderous reputation confirmed, outlaw bikers featured in a new burst of exploitation shockers, with Satan’s Sadists (1970), Angels Die Hard (1970), Hell’s Bloody Devils (1970), The Hard Ride (1971), and Under Hot Leather (aka The Jesus Trip, 1971) – the latter seeing a convent overrun by outlaw bikers. The biker flick even gleefully capitalised on the Altamont furore, the hippy commune replacing the small-town community as the target of biker carnage in Angel Unchained (1970) and the ultra-violent Angels, Hard as They Come (1971).

After this brief and bloody renaissance, however, the biker flick finally ran out of road. This was not due to public disenchantment with biker violence, nor simply to audience boredom. More important was the fact that the image of the outlaw biker became (hushed voice) acceptable. By the mid-1970s the biker archetype had been rehabilitated as a stock image of Americana. Taking his place alongside Mom and apple pie, the biker became an abiding signifier for the sturdy egalitarianism and healthy independence of the ‘American Way’. Indeed, this process of incorporation was detectable in the tail end of the biker genre itself. In 1969 the National Football League actually encouraged Joe Namath (star quarterback of the New York Jets) to take the lead in C.C. and Company, Namath starring as an all-American ‘good guy’ biker. In The Losers (1970), meanwhile, outlaw bikers join forces with ‘The Man’ – a biker gang helping the CIA bust out American POWs from a communist prison camp in Cambodia.

During the 1980s and 1990s the success of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s character in The Terminator (1984) and Terminator 2 (1991) testified to the continued Hollywood appeal of the outlaw biker as an image of dark menace. Elsewhere, the biker gang also figured in postmodern nostalgia movies such as Rumble Fish (1983) and The Loveless (1983), as well as ironic pastiches like Killer Klowns From Outer Space (1988) and Chopper Chicks in Zombietown (1991). For the masters of exploitation cinema, however, the biker flick was an exhausted genre. Co-opted into mainstream culture, the semiotics of outlaw bikerdom were no longer a dependable source of outrageous excess. Instead, the deranged serial killer and the chainsaw-wielding maniac increasingly replaced the savage biker as a symbol of terrifying Otherness as exploitation filmmakers sought new ways to ‘show the squares some class’ and ‘give ‘em a whiff of those kicks they’ll never know…’