Oh, the helplessness of the professionals, and the creative joy of the independent film artist, roaming the streets of New York, free, with his 16mm camera, on the Bowery, in Harlem, in Times Square, and in Lower East Side apartments – the new American film poet, not giving a damn about Hollywood, art, critics, or anybody.

In film, most new waves emerge not from soundstages and studios, but from the streets. The aesthetic revolution of postwar Italian neo-realism and of the French and British new waves in the early 1960s drew their vitality directly from the teeming milieus of Rome, Paris and London. The New York avant-garde film movement of the 1960s was no exception. Rejecting the factory-style artifice of Hollywood films, whose worlds were literally built from scratch on empty soundstages, underground filmmakers found their reality in the world around them. The city’s buildings and streets became a vast impromptu studio in which personal, idiosyncratic movies were made – movies as eclectic and varied as the city itself.

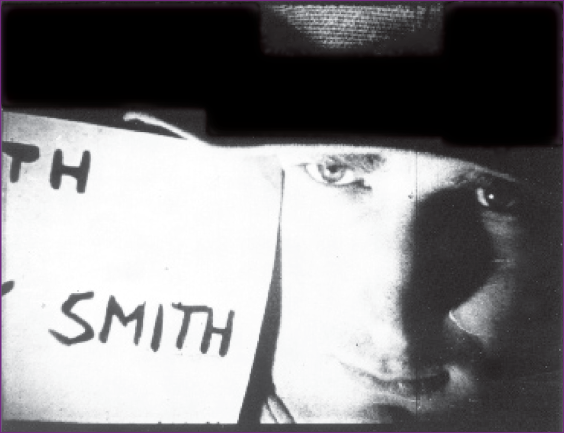

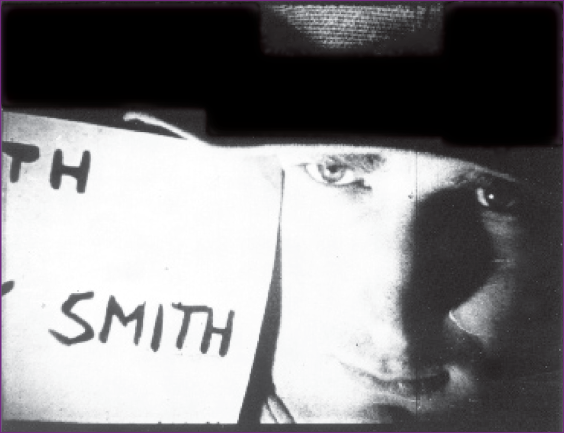

FIGURE 24 Jack Smith in Blonde Cobra

Ken Jacobs reveled in the bohemian splendor of cheap Lower East Side tenement flats and rooftops to create Little Stabs at Happiness (1960) and Blonde Cobra (1963). George and Mike Kuchar made the Bronx a cinematic wonderland, creating tawdry and hilarious versions of the Hollywood spectacles they watched as teenagers in the 1950s at the Loew’s Paradise. Working with the open-eyed curiosity of the Lumière brothers, Andy Warhol turned his impassive lens on the Empire State Building, and let the camera roll for eight hours.

Cinema, after all, is an art form rooted in photographic reality, so it makes perfect sense that the films of the New York underground provide, among their artistic breakthroughs and triumphs, a vibrant record of what life felt and looked like in the 1960s.

To create Still (1971), his monumental study in superimposition, in which different layers of time exist in the same frame, Ernie Gehr trained his camera on a section of a block on Lexington Avenue. A mesmerising and confounding experiment in the manipulation of time and space, Still is also an impressionist urban portrait that takes delight in the changing patterns of sunlight on a tree, the comings and goings of people in a small diner and the flow of traffic as it passes in front of the camera.

Of course, New York City gave its filmmakers more than just a physical setting – it also provided a culture, and a means of distribution, exhibition and promotion. In 1962, the Filmmakers’ Co-operative was founded, providing distribution to any filmmaker who submitted a print. Formal and informal venues emerged around the city, offering a moveable cinematic feast to an adventurous and sizeable audience. The Charles Theater, on Avenue B and East 12th Street, presented open house screenings from 1961 to 1963. The Bleecker Street Cinema briefly attempted to cash in on the scene with midnight screenings in 1963 – including the legendary double-feature premiere of Blonde Cobra and Flaming Creatures. Ken Jacobs organised screenings in his lower-Manhattan loft; it was here that the Kuchar brothers first showed their 8mm comedies.

Interest in avant-garde films was bolstered by sustained press coverage. The quarterly journal Film Culture, and the Village Voice, with its weekly ‘Movie Journal’ column by Jonas Mekas, provided a public forum where underground films could be championed and discussed, and placed in the context of a thriving international film scene that included Hollywood movies as well as the foreign films playing in the city’s numerous commercial art-houses.

Further enhancing the impact of the New York film underground throughout the 1960s was the fact that it fit into a much broader counterculture scene that encompassed many art forms. The spontaneity and rebellious nature of underground film echoed the beatnik writing of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac; the painting of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol; the music of John Cage; and the live performances of the Living Theater, Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown, to name just a few. When Warhol released Chelsea Girls in 1966, it became a commercial success, quickly moving from a run at the Filmmakers Cinematheque on West 41st Street to a 57th Street art-house, where it played for months, and was reviewed by Newsweek, which called it ‘one of those semi-documents that seem to be the most pointed art forms of the day’.2 The underground also benefited from controversy and scandal. The sexually outlandish and explicit Flaming Creatures was banned by New York City, which was trying to clean up its public image before the 1964 World’s Fair. Warhol’s epic-length movies in which ‘nothing’ happened became the subject of cocktail-party ridicule by people who had, of course, never actually seen the films.

The notoriety and attention that gave the New York film underground a rare moment of impact and exposure have long faded, replaced by an independent film scene today that is deeply intermeshed with the mainstream. The city, too, has changed, becoming more commercial. So in a way, this retrospective is as much a portrait of a vanished city as it is a survey of a film movement that was truly independent.

This essay first appeared as programme notes for a film series held at the American Museum of the Moving Image (Astoria, New York), 4 November – 3 December 2000.