Gross-out speaks in a voice that demands to be heard because it represents a powerful strain in contemporary American culture. And it demands to be listened to closely: in the free-form give-and-take of its licentious manner, it speaks in the voice of festive freedom, uncorrected and unconstrained by the reality principle – fresh, open, aggressive, seemingly improvised, and always ambivalent.

[T]here is such a thing as good bad taste and bad bad taste. It’s easy to disgust someone; I could make a ninety-minute film of people getting their limbs hacked off, but this would only be bad bad taste and not very stylish or original. To understand bad taste one must have very good taste.

Heads are crushed, cars explode, a schoolroom full of ‘special’ students get massacred, and there’s a scene of a dolphin-person with two masturbating superheroes against a backdrop of an American flag. The Tromeo and Juliet monster penis even makes a cameo appearance. Yes folks, this is quality Troma.3

INTRODUCING THE OBSCENE

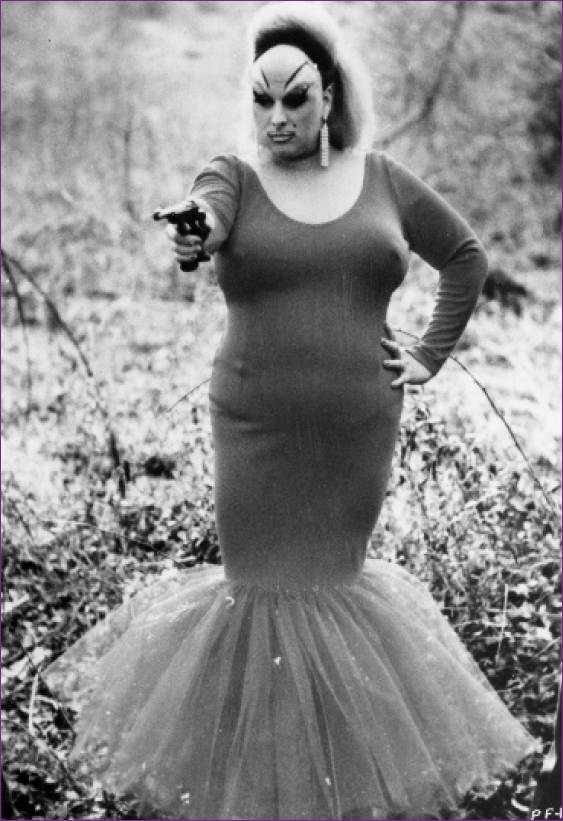

Whether embodied by the excrement-eating transsexual Divine, the chemically-altered, melted-down figure of the Toxic Avenger or the pig-faced, penis-empowered heroine of Tromeo and Juliet (1996), the films of John Waters and Lloyd Kaufman have come to define the American underground’s ability to shock and outrage. With films such as Multiple Maniacs (1970), Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1975) and Desperate Living (1977), Waters pioneered an ‘aesthetics of gross’ that differed greatly from the Hollywood images of excess available at the time. It was not merely the vast downward shift in production values, pacing, acting and effects work that distinguished his works from mainstream attempts to offend. Rather, it was the fact that his cross-gendered, orally-obsessed filth fetishists belonged to a wholly distinct order of trangressiveness.

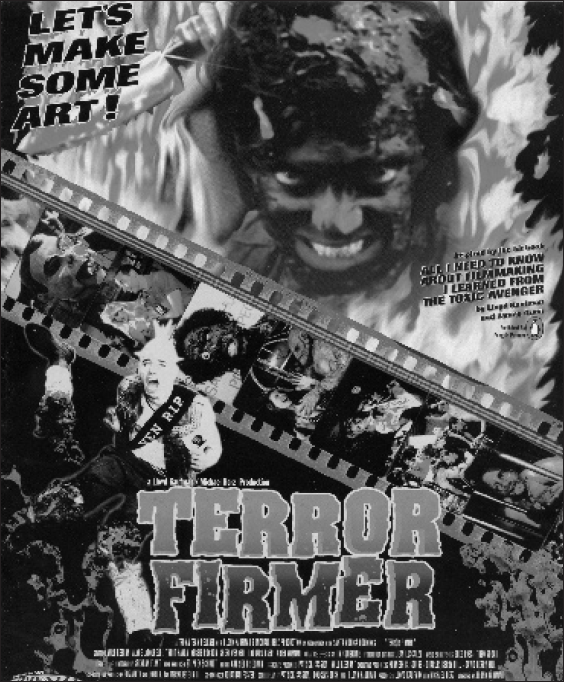

It is this same drive towards violation that also characterises the work of Lloyd Kaufman, the self-styled ambassador of bad taste whose films include The Toxic Avenger (1986), Tromeo and Juliet and Terror Firmer (1999). Working through his independent production house ‘Troma Pictures’, Kaufman has created a series of underground classics whose imagery trades on grotesque and humourous depictions of the body – notably blood, buns and bodily dismemberment – whilst also utilising established literary and cinematic motifs for parodic purposes. For instance, Kaufman’s daring rendition of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet periodically disrupts ‘accepted’ and ‘official’ passages from the Bard’s text with a far more bodily form of communication that sees bouts of flatulence, masturbation and mutilation interrupting the dialogue between the star-struck lovers.

Although Kaufman’s version/vision of the tale ends on a far more upbeat note than its source material, these changes are made with an end to achieving obscene and distasteful comedic effect. So, Tromeo (Will Keenan) and Juliet (Jane Jensen) manage to overpower the heroine’s father at the point where he threatens to ‘kill and fuck her at the same time’ for disrupting his plan to marry her off to ‘King Meatball’ Arbuckle (Steve Gibbons), a local abattoir entrepreneur. Having forced the head of the evil patriarch through a television monitor, the couple proceed to ram ‘Tromalite’ tampons up his nostrils and beat him repeatedly with a copy of the Collected Works of William Shakespeare. After defeating their oppressor, the white-trash lovers emerge into the sunlight to the shocking revelation that they are in fact brother and sister. This discovery causes a momentary pause in the lovers’ plans before Juliet announces: ‘Fuck it, we’ve come this far!’ With this the pair tear away in Tromeo’s car before an epilogue reveals the fruits of their blissful union: a pair of misshapen, bone-headed, toxic toddlers – the result of incestuous inbreeding.

As this brief description implies, Kaufman’s ‘gross-out’ construction of the human form and its secretions are anchored by an anti-authoritarian, distinctly un-American sentiment – one that has been embraced by the marginal and dispossessed groups circulating around America’s youth population through such subcultures as death metal music and underground film. For these groups, Troma productions are seen as using comically offensive, disgusting and disturbing images to examine more serious issues and inequalities within US society. As Brian Matherly notes:

Troma isn’t all about boobs, blood and goo though. Through their skewed lenses, the Troma team have tackled such sensitive issues as AIDS (Troma’s War), parental abandonment (Toxic Avenger 2), incest (Tromeo and Juliet), and gender confusion caused by years of sexual abuse (Terror Firmer).4

Indeed, it could be argued that whereas (early) Waters utilised the independent exhibition circuit as a way of circulating his obscene images of a seriously dysfunctional America, Kaufman has taken the practices and politics of underground cinema even further. Alongside his associate Michael Herz, the pair have turned Troma Pictures into a vertically-integrated production company, responsible for disseminating images that, while fiendish and quite often ‘sick’, are also free from big-budget studio interference. As a result, Troma not only produces films – they also distribute a wide range of existing American underground and European cult classics on celluloid, video and DVD, and stage underground film festivals as well.

What unites the films of both directors is the use of gross-out as a means of shocking and scathing viewers in a way that separates their work from mainstream cinematic efforts to disturb. To this extent, we might hypothesise that the works of both Waters and Kaufman point to differences between underground and mainstream cinematic gross-out that are not just a matter of degree, but rather a matter of kind.

These distinctions are most evident in the commentaries that have circulated around the work of both directors. Reviewers frequently emphasise the visceral effects of the films’ narratives in very bodily terms, e.g., ‘This is some of the funniest shit I’ve seen in a long, long time’.5 Moreover, this type of underground gross-out is often interpreted as a ‘pure’ effect distinct from that offered up by mainstream film culture: ‘Forget all you know about what Hollywood considers ‘gross-out’ comedy and prepare yourself for one of the most offensive, distressing and viciously funny satires ever made’.6

Here we will seek to determine just what this difference in kind amounts to. Our aim is to explicate the curious pleasures of underground gross-out versus the tamer, relatively ‘tasteful’ Hollywood alternative, and to argue for the existence of a ‘pure’ gross-out genre – one that bears an essential connection to the aesthetics and practices of underground filmmaking. Using the work of Mikhail Bakhtin, we will examine the visceral quality of Waters’ and Kaufman’s images, as well as their films’ appeal to underground audiences. One advantage of a Bakhtinian analysis is that it allows for the work of both directors to be considered via notions of the carnivalesque, grotesque body. Finally, we will show how the unruly nature of these directors’ gross-out spectacles indicates the potential of the American cinematic underground to subvert the physical, stylistic and ideological norms held in check by the Hollywood system.

UNDERBELLY, UNDERGROUND

In his 1990 book, The Philosophy of Horror; or, Paradoxes of the Heart, Noël Carroll proposes that the spectatorial response of ‘art-horror’ be understood as a compound emotion directed towards onscreen entities – monsters – that strike us as being both physically threatening and conceptually ‘impure’. Carroll then analyses his notion of impurity using the terms originally suggested by anthropologist Mary Douglas in her classic 1966 study, Purity and Danger:

Douglas correlates reactions of impurity with the transgression or violation of schemes of cultural categorisation.… Things that are interstitial, that cross the boundaries of the deep categories of a culture’s conceptual scheme, are impure.… Faeces, insofar as they figure ambiguously in terms of categorical oppositions such as me/not me, inside/outside, and living/dead, serve as ready candidates for abhorrence as impure, as do spittle, blood, sweat, hair clippings, vomit, nail clippings, pieces of flesh, and so on…7

By adding impurity (understood in the culturally-specific sense of category violation) to threat in his above definition of art-horror, Carroll is able to distinguish this ‘sophisticated’ spectatorial response from ‘mere’ fright or even terror in the face of something interpreted as dangerous and intending to cause physical harm. In other words, it is precisely the addition of impurity to threat that separates the complex emotion of art-horror – and the horror genre on the whole – from the simple emotion of what might be called ‘art-fear’ (and those other genres which aim, each in their own way perhaps, at frightening audiences). What is left unresolved in Carroll’s account is the question of what impurity without threat, or impurity minus threat amounts to. That is, what can we say about those films in which particular objects, entities or events are presented to the viewer as disgusting and repulsive – in short, as ‘gross’ – without their also (simultaneously and independently) being presented as dangerous and intending to cause physical harm? Carroll does not perform this operation in The Philosophy of Horror, which is not surprising considering his focus on those films in which perceived threat is held to be at least a necessary condition of horror-genre membership.

The cinema of both Waters and Kaufman, in which gross bodily activities are annexed to some form of comedic effect, provides us with the basis for a generic definition of the ‘pure’ gross-out film. Here, disgusting depictions are just as likely to be accompanied by humourous elements as by horrific ones, making their intended responses multiple and ambivalent. For example, scenes from The Toxic Avenger, such as the one in which a bunch of street-trash assassins holding up a fast food joint are violently turned into human taco shells, ice-cream and other menu items by a sub-humanoid superhero, is just as capable of generating howls of laughter as screams of terror.

It is precisely the ability of the human body’s gross-out gestures to provoke reactions of humour and disdain that governed Bakhtin’s classic study of physiological transgression, Rabelais and His World. In this volume, Bakhtin charted what he saw as the ‘civilising’ and restraining processes that had been enacted against public display of the body from the seventeenth century onwards. During this period, both official acts and informal sensibilities mounted an increasing regulation of the human form, its gestures, waste products and secretions that still remains at play in (mainstream) contemporary society. For Bakhtin, the battleground for accepted notions of the human form dominated the policing of popular festivals, carnivals and their related bawdy representations. For instance, he argued that the work of François Rabelais focused on unruly feasts, carnal celebrations and unruly bodily representations that used comedy, excess and physiological ‘gross-out’ as a way of destabilising official power structures. Whether occurring through the absurd and fantastical scenarios of Rabelais’ work or the gross-out displays of public farting, belching and feasting that occurred in carnival activities across Europe, the ‘carnivalesque body’ points to a wider suppression of established order and physical restraint. As Bakhtin noted:

One might say that carnival celebrates temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marks the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms and prohibitions.8

For Bakhtin, the social dimension of carnival practices was marked through the principle of a ‘world turned upside down’ – a politics of subversion that saw everyday practices temporarily suspended and parodied as a way of drawing attention to established hierarchies and dominant beliefs. Here, it would not be uncommon for a beggar to be allowed to parade as a king, while women were given a free reign over sexual and social practices, all in marked contrast to the ‘normal’ restrictions placed on their behaviour.

Bakhtin argued that the carnivalesque body stands in opposition to the obsessive ‘aesthetics of beauty’ governing Renaissance constructions of the human form. Indeed, it could be argued that if modern society privileges the clean, sculptured and co-ordinated body, then the carnivalesque emphasises the body that is overwhelmed by its own gestures and secretions. This is a physiology that is dominated by libido rather than rational thought, a human form that is beset by its own tremors and spasms rather than being restrained by order and cognitive skill. In short, this is a body that provokes both laughter and unease in the viewing spectator.

While recent theorists such as Barbara Creed have charted the gradual legal and cultural drive towards cleaning up and suppressing the more gross-out aspects of carnival, they have also outlined the various ways in which the unruly grotesque body has resurfaced in underground practices and marginal representations. Whereas Peter Stallybrass and Allon White identified a carnivalesque dimension to slum/fairground and brothel practices in their classic study The Politics and Poetics of Transgression,9 for Creed, similarly grotesque and unruly representations of the human form can be seen as circulating in disreputable genres such as the horror film. Through their obscenely comic images, these marginalised but militant cultural formations ensure the continuation today of a genuine carnival spirit.

In her 1995 article ‘Horror and the Carnivalesque’, Creed notes that central Bakhtinian features (such as an emphasis on transgression, the grotesque body and humour) are also present in modern horror cinema. As with carnival, Creed argues that, as a genre, horror films employ a transgressive drive that ‘mocks and derides all established values and proprieties: the clean and proper body… the law and institutions of church and family, the sanctity of life’.10 The body plays a central part in these subversive strategies, as indicated by Creed’s ‘Twelve Faces of the Body Monstrous’ criteria.11

However, in marked contrast to Carroll’s account of threat and impurity, Creed’s use of Bakhtin allows her to discuss the type of representation where an excess of impurity actually serves to downgrade or diminish horrific effect. As she notes, these are representations where the monstrous body is as much ‘a source of obscene humour’ as a site of terror and decay.12 For Creed, this obscene-comedic effect is particularly prominent in self-reflexive examples of the genre, where ‘postmodern horror… combined with its deliberate use of parody and excess indicate the importance of grotesque humour to the success of the genre’.13

A prime example of this self-reflexive gross-out horror is Kaufman’s Terror Firmer, an obscenely outward-looking tale which finds an independent film production being stalked by a serial killer intent on ruining the latest work of the blind, babbling auteur Larry Benjamin (played a bit too convincingly by Kaufman himself). Kaufman’s manipulation of the film-within-a-film motif facilitates not only cine-literate commentary and image-laden in-jokes – it also allows him to kill off and abuse some of his greatest Troma creations. Thus, ‘Sgt. Kabukiman’ is listed as a prime suspect for the mayhem, while the actor playing the Toxic Avenger is assaulted in a pool of his own excrement – his nauseous leading lady declaring that she is ‘not gonna take this shit any longer’. Although one fat slob attempts to clear Toxie’s crud-caked passageways with an ill-aimed kiss of life (cue shots of someone literally shit-faced), the paramedics have a swifter solution to the patient’s malaise: after vomiting over the unconscious actor, they dump him ungraciously off a hospital stretcher. Other notable examples of gross-out humour in Terror Firmer include the scene where Benjamin’s obnoxious and overweight producer is attacked with an axe while on an escalator. This unlikely demise allows the chubby character to examine the discarded contents of his own stomach (guts, gore and out-of-state car licence plates) as his innards are displayed before him.

While depictions of the obscene body as a source of comedy are by no means uncommon in mainstream cinema, films like Terror Firmer indicate the manner in which marginal and underground genre pictures use such imagery in markedly different ways to Hollywood. Here, an intensity of physiological corruption and display not only gratifies underground audience desires, but also challenges the strength of the viewer’s stomach as well as their endurance skills. In this respect, underground gross-out works in a different manner to the excessive ‘Bodywood’ depictions identified by scholars such as William Paul. As Paul argues in his 1994 book Laughing Screaming: Modern Hollywood Horror and Comedy, the main form of pleasure offered by Hollywood/mainstream gross-out is that which comes from allowing oneself ‘spontaneous’ feelings that may well be undesirable if reflected upon in real-life scenarios:

It is fun to indulge in feelings that in the context of the real world would give us pause, to experience the surge of vitality that comes with the sudden onset of any strong feeling. There are values in gross-out horror and comedy that have more to do with the immediacy of play than the delayed satisfaction of ultimate purpose.14

FIGURE 25 Obscene cinema: Terror Firmer

What is so striking about the case of underground gross-out auteurs like Waters and Kaufman is that, despite having many fans and admirers, their films seem far more likely to be endured than enjoyed. Whereas in the Hollywood/mainstream case the gross-out effect is primarily functional – a means of achieving the contrary generic ends of comedy (utopian in its message, according to Paul) or horror (dystopian) – for Waters and Kaufman the cinematic gross-out is often an end in itself. One regularly reads or hears about the latest ‘gross-out comedy’ or ‘gross-out horror movie’, but the possibility of a ‘pure gross-out’ film has remained purely underground. According to Paul,

Gross-out aesthetics must seem an oxymoron since aesthetic means the beautiful, implying a sense of decorum and proportion singularly absent from most of these films. This more usual definition was in fact a main ambition of earlier mainstream Hollywood films, which strove for middle-class respectability.…[N]ever before had an ambition to grossness in itself become such a prominent element in mainstream Hollywood production.15

If our thesis is correct, however, then the ambition to ‘grossness in itself’ that Paul identifies in recent Hollywood comedies and horror films indicates less a radical change in aesthetic sensibility than a radical change in the way already-existing generic aims have been strategically and formally achieved.

THE PURSUIT OF PURE GROSS-OUT: THE EARLY FILMS OF JOHN WATERS

If it is indeed the case that Hollywood cinema fails to provide genuine gross-out thrills, the successful pursuit of an aesthetics of ‘pure gross-out’ can clearly be found in the early films of John Waters. This is partly seen in the fact that his formative productions are not themselves generically situated in any clear manner; that is, they shift uneasily between definitions of comedy, horror and the absurd. Moreover, these productions connect a raw, even experimental, underground filmmaking style with depictions of disgusting characters, objects and events. As Jack Stevenson notes, ‘Anyone could haul out stock grotesqueries and assault audiences with bucketfuls of bad taste, but Waters had mastered a certain ambiguity of intention that was the “active ingredient” in his filmmaking. Maybe he really was a fucked-up sonofabitch’.16 A corollary to these two points is that Waters’ films seemed to become less ‘purely’ gross just as they became more mainstream.

As numerous critics have observed, beginning with Hairspray in 1988, the dark violence, perverse sexuality and largely incoherent narratives of Waters’ earlier work was replaced by sweeter, often nostalgic storylines. This sentimental affect was assisted by bigger budgets and the familiar presence of Hollywood stars (e.g., Johnny Depp, Kathleen Turner) and pop-culture icons (e.g., Deborah Harry, Patricia Hearst). Implicit in this shift towards the mainstream was Waters’ move away from the carnivalesque via the courting of actors who define what Bakhtin characterised as the ‘new bodily canon’, i.e., those represented as possessing ‘an entirely finished, completed, strictly limited body, shown from the outside as something individual’.17

This stands in stark contrast to the forms of physiological abnormality and transgression present in Waters’ early films. For instance, although Stevenson calls it a mere ‘marketing gimmick’,18 and Waters himself admits that it was ‘conceived as a negative publicity stunt’,19 the aesthetics of pure gross-out are fully operative during the infamous finale of Pink Flamingos. Justin Frank is hardly exaggerating when he identifies this film’s concluding scene as ‘the most famous… in all underground cinema – the underground equivalent of the shower scene in Psycho’.20 Pink Flamingos traces the inevitable victory of Waters’ transvestite diva Divine and ‘her’ equally eccentric family in a battle against the self-consciously twisted and social-(anti)-climbing Marbles (Mink Stole and David Lochary) for the title of ‘The Filthiest People Alive’. In the film’s notorious postscript, Divine stops on a street in downtown Baltimore to pick up the freshly-laid turd of a small dog. Waters’ own recollection of what happens next is as good a description as one could possibly want: ‘[she] put it in her mouth. She chewed it, flicked it off her teeth with her tongue, gagged slightly, and gave a shit-eating grin to the camera. Presto – cinema history!’21

What is it about this simple, if sick and twisted, act of coprophagy that enabled it so quickly to obtain the status of gross-out legend? (Just try entering the words ‘Waters’, ‘shit’ and ‘divine’ into an Internet search engine and see how many thousands of hits you come up with.) After all, the turd might have been – it surely should have been! – a fake. In fact, however, it may not matter ultimately whether Divine nibbled on a real piece of crap that afternoon or just an expertly-crafted shit simulacrum. What matters is that Waters succeeded in making viewers believe she ate shit; not in order to make them laugh (though he was happy for them to do so), and not so as to horrify them (in any but a metaphorical sense of the term), but in order to give them a pure gross-out they would not soon forget.

This success was obtained primarily through Waters’ concerted effort at achieving maximum verisimilitude through the adoption of traditional documentary film technique: the scene was shot in real time, on location, using natural light, with minimal cuts, etc. This was merely an extension of the same underground aesthetic (dictated as much by budgetary constraints as by any kind of ‘principle’) dominating Pink Flamingos and Waters’ early work as a whole. The shit-eating case, despite its (assumed) status as a truthful representation, is actually not dissimilar to that of such fictional/pseudo ‘snuff’ killings in 1970s exploitation horror movies such as Snuff (1976) and Cannibal Holocaust (1979). In both of these pictures, while the gruesome murders depicted on-screen were only staged re-enactments of the real thing, extraordinary numbers of viewers bought into the faux documentary charade and were convinced that they were watching actual snuff cinema. Had the production values of these films, including Pink Flamingos, been of a higher, more ‘polished’ and ‘above-ground’ (read ‘Hollywood’) standard, most viewers would not have been anywhere near so quick to buy into their signature displays of transgression.

FIGURE 26 Divine in Pink Flamigos

However, unlike cases of pseudo-snuff cinema – as well as such modern ‘shock-horror’ classics as Eyes Without a Face (France, 1959) and Suspiria (Italy, 1977) – Pink Flamingos does not ‘dilute’ its disgust with horror, as there is no obvious or significant physical threat implied in Divine’s shit-eating spectacle, save the digestive harm she might have caused herself. (Waters reports how that same evening, at the film’s wrap party, Divine rang the emergency ward of the local hospital stating that her ‘retarded son… ate some dog faeces and I’m wondering if he can get sick?’22) Beyond this, the distinctly underground sensibility of Pink Flamingos can be seen in the film’s raw, unfiltered, uncensored content; the haphazard camerawork and half-arbitrary mise-en-scène; the campy, over-the-top nature of Divine’s performance; and the lack of firm distinctions between characters and the actors (often non-actors) who play them. Together these features operate as an extra-diegetic parallel of sorts to the disgusting acts depicted within the diegesis: Pink Flamingos is itself bad taste, although, as Waters would say, it is ‘good bad taste’ not ‘bad bad taste’.

Though it might provoke a degree of awkward laughter, most viewers would hardly admit to the final scene’s qualifying as particularly funny either. Arguably, the film has its amusing moments – in particular the scenes involving Mama Edie (Waters regular Edith Massey), as an old woman who spends most of her time worshipping eggs while sitting in a playpen dressed in nothing but a bra and girdle. However, even these unconventional scenes hardly fit in the ‘comedy’ category in any straightforward generic sense of the term. Divine’s fabled act of shit-eating, though it may have been conceived of merely as a ‘negative publicity stunt’ to be tacked on to the end of Pink Flamingos, nevertheless stands as a perfect encapsulation of all that comes before it in the film. It represents a minimalist display of multiple transgression (abjection, impurity, boundary-crossing) without the distraction of mainstream genre conventions that would effectively ‘impurify’ the gross-out grabber.

As befitting Desperate Living’s relatively more polished look (it’s $65,000 budget was much bigger than any of Waters’ previous productions), the central gross-out scene in this film occurs midway through the story and is no longer minimalist in either style or duration. The emphasis on multiple transgressions is still in place, but now the presentation is extended, lasting several minutes, and with the disgusting displays piled on to such an extent that the sheer spectacle of the sequence serves to render the loose but inspired narrative utterly inconsequential.

Waters himself has called the scene in question ‘more outrageous than any [other] in the film’,23 and for good reason. The director’s characterisation of the film as a ‘lesbian melodrama about revolution.… A monstrous fairy-tale comedy dealing with mental anguish, penis envy, and political corruption’24 suffices for present purposes. The scene opens with butch lady wrestler Mole McHenry (Susan Lowe) returning home from a sex change operation in Baltimore to her ditzy, massive-bosomed girlfriend Muffy St. Jacques (Liz Renay). To Mole’s dismay, Muffy is repulsed by the very sight of her partner’s penis transplant, and vomits after Mole climbs on top of her in an over-eager attempt at showing off the new organ. Muffy pleads with Mole to cut it out – and cut it off – and the depressed and defeated Mole promptly obliges, using a pair of garden shears to perform the self-surgery. Showing no mercy to his audience, Waters does not end the scene with this castration operation: while Mole cries out in agony, Muffy begins to sew up her girlfriend’s bleeding crotch, reassuring her ‘I’ll love it, Mole. I’ll love it, feel it and eat it just like old times’. As for the prosthetic penis, after Moles tosses it out the front door, a dog comes along, sniffs around for a while and finally starts nibbling on it.

In his review of Desperate Living for the Baltimore Evening Sun following the film’s premiere, Lou Cedrone declared: ‘Waters is a little bent. No, he’s twisted, maybe even broken. If you are amused by vomit, blood, cannibalism, cruelty to children, and rats served as dinner, you may want to see the film. It would be fun as low-low camp if it wasn’t so sick’. R. H. Gardner of The Sun, another Baltimore daily, somehow managed to top Cedrone:

John Waters specialises in works of an unbelievably gross and offensive nature. No contemporary filmmaker has presented the human race in so disgusting a light. Waters’ characters are not simply hideous, they affront the soul. They exude the aroma of outside toilets. They achieve a grotesqueness for which the adjective ‘repulsive’ leaves something to be desired.25

Interestingly, it is not entirely clear whether these reviews are meant to be positive or negative in their evaluations of the film. It would be one thing if Waters, like his more mainstream contemporaries, intended for the grossness and offensiveness of Desperate Living to serve (functionally) as a source of humour, or perhaps of horror. Were that the case, then the striking statements by Cedrone (who comes close to accusing Waters of trying unsuccessfully to make a campy comedy) and especially Gardner could be taken as indicating the director’s failure. But not surprisingly, given his long-standing efforts at creating a cinema of pure gross-out, Waters himself takes both statements as compliments: ‘the[se] two leading local critics… who had given up on getting rid of me years ago, came through with just the kind of review I love to get’.26 This offhand remark indicates something other than a desire on Waters’ part for negative publicity; it signals his appreciation for those in the press who eventually learned to judge his work by its own (underground) standards, rather than according to the conventions of Hollywood genre cinema.

Besides lasting several minutes longer than the shit-eating scene in Pink Flamingos, the gross-out sequence in Desperate Living described above differs from its predecessor in giving up any pretence to verisimilitude. Instead, it emphasises – even revels in – the obvious fakeness of the situation: yet another underground (and avant-garde) filmmaking strategy present in the works of Jack Smith and Andy Warhol, among others. Besides the histrionic, hyperbolic performances and the see-through set design, Mole’s makeshift member looks more like a dime-store dildo than a real-if-transplanted penis, and Muffy’s vomiting act has nothing whatsoever on The Exorcist (1973). But here it is precisely the fact that there is no attempt to hide the artifice that adds to the gross-out flavour of the scene. Fully aware the whole time that what we are watching is fake – there is not even a moment of suspended disbelief – we are forced to wonder both why the director is doing this at all and why we are allowing him to do it to us.

BLOOD, BUNS AND BELLY LAUGHS: LLOYD KAUFMAN AND TROMA

With their uneasy blend of sick humour, bodily fluids and diverse displays of gross-out, Lloyd Kaufman’s films share many of the same offensive qualities marking the early works of John Waters. Similar to the excess orality of Pink Flamingos, Kaufman and Herz’s The Toxic Avenger offers up multiple images of unruly feasts, riotous gatherings and body secretions (notably blood, semen, excrement and toxic urine), as well as depictions of the grotesque body in a variety of incarnations. These unsavoury images are stitched together in a format that fuses parodic film references (e.g., to old Chaplin movies and 1930s ‘cliff-hanger’ serials) with nods to experimental underground techniques (including a ‘toxic transformation’ with colour codings straight out of Stan Brakhage). The film focuses on a deformed superhero who defends the people of small town Tromaville from political corruption and violent crime in a narrative that uses the grotesque body to parody the norms, ideals and values associated with the American dream.

By centring the film at ‘The Tromaville Health Club’, The Toxic Avenger establishes the ideal of a worked-out, toned and trimmed, pumped up and primed physical form (this being reiterated by the theme song ‘Body Talk’ that accompanies the gym sequences). From the outset, however, the film degrades and displaces this notion of bodily integrity. For instance, it is implied that Tromaville’s corrupt Mayor Belgoody (Pat Ryan) has been allowing the illegal dumping of toxic waste in suburban areas, thus ensuring human decay and infection. In this environment, it is the grotesque, carnivalesque frame that comes to replace the body beautiful.

Indeed, The Toxic Avenger splits Bakhtin’s conception of the grotesque, comedic body into two distinct forms. Firstly, there are the gargantuan, slob-like and food-obsessed figures such as Belgoody (whose excessive orality is signified by his insistence on eating fast food whilst receiving an erotic massage), who are clear matches for the oversized and insatiable creatures found in writers such as Rabelais. Alongside these (literally) larger than life figures exist the emaciated males – including the film’s hero, Melvin (Mark Torgl) – whose meagre frames and jerky, uncoordinated gestures contradict the healthy images of masculinity that the film is seen to critique. In Bakhtinian terms, this split represents a disjuncture between the essentially open, tactile and unfinished body of carnival and the sleek, sculptured and ‘closed’ human ideal that came to replace it. As Bakhtin states in Rabelais and His World:

We find at the basis of grotesque imagery a special concept of the body as a whole and of the limits of this whole. The confines between the body and the world and between separate bodies are drawn in the grotesque genre quite differently than in the classic and naturalist images.27

The distinctions between the grotesque and classical depictions of the body are present in the opening montage scene of The Toxic Avenger. Here, Kaufman and Herz shift between the vigorous exercises of the film’s key villains, Bozo (Gary Schneider) and Slug (Robert Prichard), contrasting these physically perfect but psychotic protagonists with the misshapen misfits who circulate on the health spa’s fringes. The latter include a pair of old camp queens engaged in heavy petting over an exercise machine, a grossly overweight woman eating potato chips during an aerobics routine and various male weaklings on the very edge of being crushed by their own dumbbells.

In the course of surveying this curious collection of individuals, the camera eventually settles on Melvin, the nerdy toilet attendant who is later transformed into the toxic superhero of the film’s title. From the outset, this character’s comic construction meets Bakhtin’s criteria in several ways. To begin with, Melvin’s emaciated, effeminate features provide a direct and parodic contrast to the socially-reinforced ideals embodied by Bozo’s construction of masculinity. (Melvin’s pitiful attempts at flexing his underdeveloped muscles before a locker room mirror provoke hysterical outbursts from Bozo precisely because they comically emulate his own, overblown gestures of machismo.) At the level of facial characteristics, Melvin’s bucktoothed visage – a deformity that literally prevents him from closing his mouth – further links him to notions of the grotesque.

In Bakhtinian language, Melvin’s body is perpetually ‘in the act of becoming. It is never finished, never completed, the body swallows the world and is itself swallowed by the world’.28 This is also a physique that retains a degraded, low socio-economic status (embodied by Melvin’s role as the health club ‘mop boy’), one that is intrinsically linked to the body’s more distasteful aspects. Indeed, Melvin is associated with waste matter from the start via his role as a toilet attendant. At one point Bozo even comments that Melvin is struck with a ‘shit-eating grin’, and the latter’s excremental stench serves to offend the ‘cool kids’ who hang out at the club.

Melvin’s gross-out status is confirmed by the cruel trick (played on him by Bozo and his buxom girlfriend Julie (Cindy Manion)) that unwittingly transforms him into the Toxic Avenger. Here, Melvin is cajoled into donning a pink leotard and tutu in the belief that he is about to experience a sexual encounter with Julie in the girl’s locker room. (The protagonist’s comment that he can meet her at this location whilst he is cleaning the nearby toilets once again confirms his association with waste matter.) Having been led into a darkened location, Melvin begins to kiss and fondle what he believes is the object of his affections, before a blaze of light and laughter reveal that he is in fact engaging in an erotic encounter with a goat. Having been tricked by Bozo, Julie and the ‘beautiful people’ of the health club, Melvin attempts to escape his tormentors by jumping from an upper-level window… only to land in a vat of toxic waste that has been dumped outside the venue.

FIGURE 27 A grotesque carnivalesque body: The Toxic Avenger

Melvin’s subsequent ‘toxic’ transformation more than satisfies Creed’s criteria concerning the gross-out nature of the carnivalesque body in underground and horror cinema. Here, the protagonist’s skin turns green, pulsates and oozes slime as he jerks, spasms and finally erupts into flames before an assembled audience from the health club. The scene also confirms Bakhtin’s belief that ‘exaggeration, hyperbolism, excessiveness are all generally considered fundamental attributes of the grotesque style’.29 In case the effects might be deemed too horrific, or his agony look too real, Bozo re-injects a comic angle into Melvin’s suffering by informing Julie (and thereby the film’s audience) that he is ‘faking it’. (A similar self-reflexive comment is made in Tromeo and Juliet when the heroine’s father derides his daughter’s self-inflicted transformation into a farmyard animal as ‘special effects’.)

The Toxic Avenger’s semi-humourous degradation of the body in pain is reiterated when Melvin returns home to bathe and metamorphose some more. Here, the protagonist’s skin erupts into a series of lesions which then expel a foul green liquid, while his hair falls out in clumps revealing a misshapen, swollen skull. Further, his torso and arms swell to body-builder proportions while his effeminate squealing is replaced by a far more masculine voice. This leads Melvin’s mother (on overhearing her son’s transformation through the wall) to comically misinterpret what she hears as her ‘little boy’ finally reaching puberty!

Melvin’s alteration into Toxie confirms Creed’s claim that ‘the grotesque body lacks boundaries; it is not “completed”, “calm” or “stable.” Instead the flesh is decaying and deformed’.30 This process of becoming also points to themes of metamorphosis within the carnivalesque and underground fictions that she analyses. In many respects, such images of transformation disturb ‘not only what it means to be human’,31 but also what it means to be gendered. Although Melvin’s toxic makeover results in a newly hyper-masculine appearance, his chemical fusion also results in the permanent moulding of the ‘feminine’ health club tutu onto his flesh. As a result, his body connotes a grotesque excess of both male and female signifiers that rival the transgendered glory of Divine in John Waters’ early productions.

The connection between the grotesque, carnivalesque body and sexual ambiguity is not only confined to Toxie and his opponents (who include cross-dressing martial artists and over-decorated and rouged street punks), but rather forms a consistent trait in all of Kaufman’s work. Tromeo and Juliet, for instance, features a heroine who transforms herself into a pig-faced monster with an excessively long phallus in order to avoid the advances of an amorous suitor. The protagonist’s uneasy relation to traditional notions of femininity are established in an earlier dream sequence, when Juliet imagines her belly swollen and erupting with filth in a bizarre parody of the birth act. This sequence supports the notion that the carnivalesque body ‘gives birth and is born, devours and is devoured, drinks, defecates, is sick and dying’.32 Even more surreal is the figure of Casey (Will Keenan), a cross-dressing killer from Terror Firmer. Although Casey appears to the film’s heroine in a variety of fantasised ‘macho’ poses, he is only able to pleasure her with the aid of a green pickle, after his father (played by porn superstar Ron Jeremy) castrates him and forces him to dress as a female.

With their outrageous content, parodic, scathing humour and emphasis on bad taste, both John Waters and Lloyd Kaufman have confirmed the American underground’s ability to produce ‘pure’ gross-out cinema. Yet behind the muck, goo and outlandish body imagery lies a far more serious and potentially subversive message. This relates to the ability of humour and obscene human forms to be presented in challenging and unconventional ways that are capable of overturning wider social norms and values. Bakhtin argued that ‘Whenever men laugh and curse, particularly in a familiar environment, their speech is filled bodily images’.33 The films of our two underground auteurs have turned such body talk into an aesthetics and politics of gross-out, now residing in the obscene underbelly of Hollywood.