B1A

The Viceregal Legacy

In 1880, the people of Ontario learned that their next lieutenant governor was to be John Beverley Robinson, whose father and namesake had been a prominent lawyer, politician, and chief justice of earlier times.1 Soon after his appointment, the new lieutenant governor struck upon the idea of a portrait gallery dedicated to his predecessors and all those who would come after him—a Gallery of Governors, as it were.2 This pet project was largely motivated by the lieutenant governor’s keen sense of Ontario’s history, and his family’s influential standing among the upper echelons of the province when it was still known as Upper Canada. But patriotism and posterity were also major considerations. The portraits were intended to be a source of pride among all classes of people—not only in Ontario, but in the rest of Canada as well. At a time when nationalism was on the rise, and when the imperial connection to Great Britain was still of paramount importance to a large segment of the Canadian population, it was perfectly reasonable for Lieutenant Governor Robinson to think that the collected portraits of his antecedents would inspire a devotion to the Crown for generations to come.

Lieutenant Governor Robinson’s method of assembling his collection of viceregal portraits quickly became well established. In each case, he began by looking for a suitable likeness, which was then borrowed or photographed so that George Berthon, a renowned Toronto-based artist, could work up an appropriately dignified copy in oils.3 By the spring of 1881, the lieutenant governor was anxious to track down a portrait of Major General Sir Isaac Brock, who served as president (or acting lieutenant governor) of Upper Canada prior to his death in 1812. The logical place to begin such a search was Guernsey, the Channel Island where Brock was born and raised. To aid in the search, the lieutenant governor enlisted the assistance of a brother who was then living in London. But Colonel Charles W. Robinson was not optimistic. He recalled that some years earlier he had attempted to find a portrait of Brock for the Royal Hospital at Chelsea and been told that none existed.4 The lieutenant governor was not deterred, however, and it appears that a journalist-turned-historian gave him reason to hope.

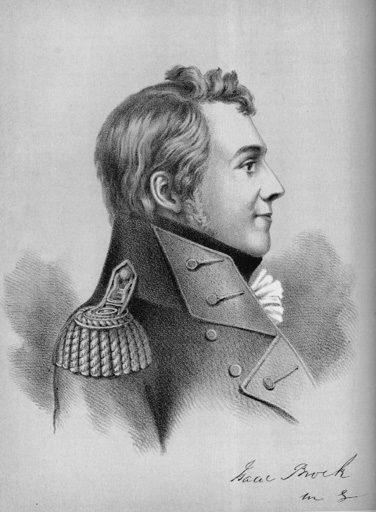

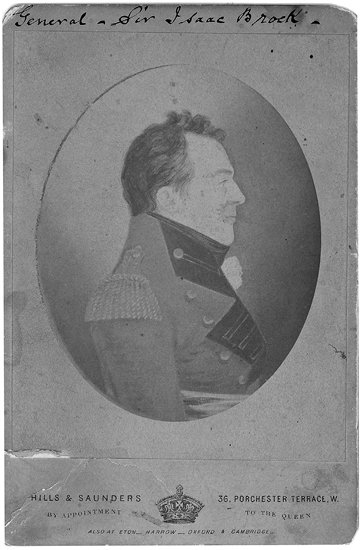

In 1880, the same year that Lieutenant Governor Robinson began his mandate, John Charles Dent published the first volume of his Canadian Portrait Gallery, which was followed by three additional volumes chronicling the lives of Canada’s leading personalities. The popularity of these illustrated books coincided with the emergence of a culture in which the enhancement of text with images was becoming increasingly common. Not surprisingly, Brock’s entry in the Canadian Portrait Gallery warranted a lavish colour portrait using the chromolithography process (fig. 1). The resulting illustration, a profile in muted tones, was similar to a wood engraving (fig. 2) that had appeared several years earlier in the Globe, a Toronto newspaper edited by Dent.5 Both interpretations were based on a portrait owned by Brock’s relatives in Guernsey, who had only just recently allowed it to be photographed for Dr. John George Hodgins of Toronto.6 As Ontario’s deputy minister of education, Dr. Hodgins wanted to have the photograph for a display in the Educational Museum, where Brock’s likeness would serve to evoke a heightened sense of pride in being Canadian.7 As noted, the latter part of the nineteenth century was a period of nation-building. And since the central theme of this movement was a love of one’s country, heroic iconography became a mechanism for instilling patriotism among the citizenry of the new nation. Having recognized the significance of such pictures, Dr. Hodgins enquired after Brock’s portrait. His efforts were rewarded with a photograph featuring the portrait of a pleasant-looking British officer in profile facing right. Dent used this same photograph as the basis for his illustrations, one or both of which likely convinced the lieutenant governor that a portrait of Sir Isaac Brock did in fact exist.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

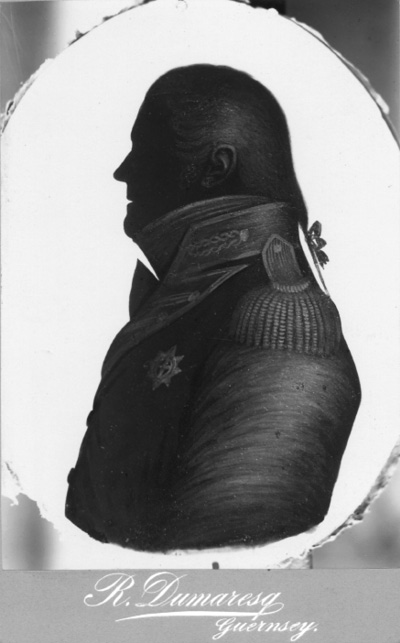

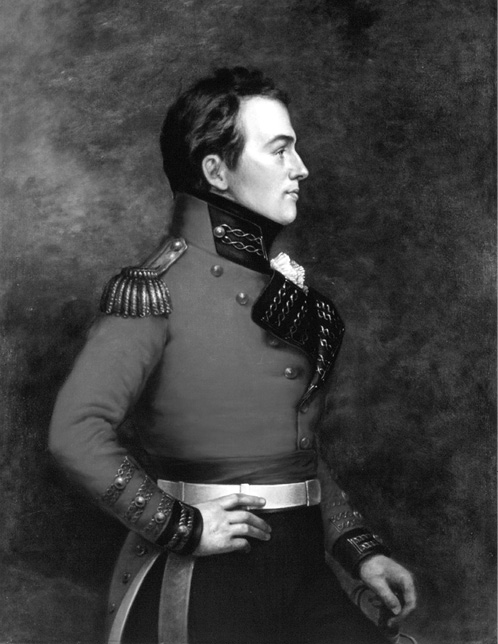

With the help of his brother, Lieutenant Governor Robinson managed to locate Brock’s profile portrait, which also brought about a complication—as there were two such portraits from which to choose. One (fig. 3) was owned by Mrs. Henry (Mary Ann Collings) Tupper, whose deceased husband was a nephew to Brock through his mother, Mrs. John Elisha (Elizabeth Brock) Tupper. The other (fig. 4) was the property of Mrs. George Huyshe, the former Miss Rosa Brock and a daughter of Brock’s brother, John Savery Brock. The discovery of two portraits called for a clarification, especially since what the lieutenant governor was really looking for was a full-faced likeness. He hoped that one of the two profile portraits might have been incorrectly described, and that one of them might in fact be closer to what he wanted. Dutifully, Colonel Robinson applied to Mrs. Huyshe for additional information.

The portrait belonging to Mrs. Tupper was found to be finely executed. But the one owned by Mrs. Huyshe was rendered in a somewhat cruder fashion, although the face was very well done.8 What Mrs. Huyshe never mentioned, however, was that both portraits were done in profile and nearly identical. Moreover, hers was obviously a copy. Because it was known to have belonged to her father, this reproduction was likely commissioned by him as a memento of his deceased brother.9 And since the original was considered more appropriate for the lieutenant governor’s purposes, Mrs. Tupper very reluctantly allowed it to be sent to London to be copied—not only by a photographer, but an artist as well. Colonel Robinson thought the latter means of reproduction might suffice for his brother’s gallery. With this in mind, he made arrangements for the portrait, measuring only some eight inches by nine (20.3 x 23.4 cm), to be duplicated twice that size in oils.10 The colonel also arranged for a smaller watercolour copy in sepia tones, which he planned to donate to the Royal Hospital at Chelsea (fig. 5).11 The artist commissioned for both works was Miss Alice Kerr-Nelson, “a lady with a great deal of talent” whose straitened circumstances forced her to turn to painting for a livelihood.12 Fortunately for Colonel Robinson, Miss Kerr-Nelson was not so destitute that she required an advance, just sufficiently cash-strapped that she agreed to do the work subject to approval. Miss Kerr-Nelson wasted no time, and before long she had both portraits done and ready for the colonel’s inspection.

Figure 5.

Finished in a competent and robust manner, the oil painting Miss Kerr-Nelson presented to Colonel Robinson (fig. 6) portrayed Brock as a young officer with an intense gaze. The colonel was pleased with the results, preferring Miss Kerr-Nelson’s portrait of Brock even to Mrs. Tupper’s original (fig. 3), which he found “a rather wishy washy production.”13 Colonel Robinson thought, erroneously, that the weak effect of the Tupper original was due to the use of a combination of chalk and watercolour. Actually, it was mainly pastel with some chalk and graphite, but no watercolour. Although Colonel Robinson was partial to Miss Kerr-Nelson’s copy, it remained to be seen whether or not it would receive the viceregal nod. Colonel Robinson was fairly confident that his brother would recommend the purchase of Miss Kerr-Nelson’s painting, but he was also well aware that the lieutenant governor might insist on having Berthon paint Brock’s official portrait. Therefore, Colonel Robinson had the original portrait photographed—just in case Berthon chose to work from it.14 If nothing else, Miss Kerr-Nelson’s painting could be used as a colour guide, since the photograph was only available in black and white (fig. 7). And if the lieutenant governor decided against the purchase, Berthon could still make good use of the painting before it had to be returned or sold to someone else.15

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Having settled on this strategy, Colonel Robinson thought it best to have the painting by Miss Kerr-Nelson sent to Canada in the care of Miss Augusta Robinson, one of the lieutenant governor’s daughters. Miss Robinson happened to be in England, and so the timing must have seemed nothing short of providential.16 But Colonel Robinson’s well-laid plans were soon upset. His brother was becoming uneasy about the commission and his skepticism focused squarely on the original profile portrait, which the colonel had just gone to great lengths to have reproduced.

Lieutenant Governor Robinson, still mindful of his brother’s earlier and unsuccessful attempt to find Brock’s portrait, became more than a little concerned after reading a short passage in The Life and Correspondence of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, K.B.17 The author of this work was Brock’s nephew, and Ferdinand Brock Tupper related a very disconcerting story in one of the footnotes. Apparently, when the officers of the 49th Regiment requested a portrait of Brock in order to have it copied for their mess room, they were disappointed to learn that the family “possessed no good likeness of the general.”18 The lieutenant governor was understandably dismayed, as Tupper seemed to imply that there was no portrait of Brock—but now there were two! Troubled by this discrepancy, the lieutenant governor wrote to his brother early in January of 1882, explaining the situation.19 Colonel Robinson promptly mailed off a letter to Mrs. Tupper, and he soon had a message back. Mrs. Hubert Le Cocq, who was the former Miss Victoria Tupper, replied for her ailing mother by assuring the colonel that there had simply been a misunderstanding.

As Mrs. Le Cocq pointed out, the officers of the 49th Regiment were disappointed not because the family possessed no likeness of Brock but rather because they “possessed no good likeness.”20 In other words, the profile portrait was not considered good enough for the officers’ mess. Colonel Robinson accepted what Mrs. Le Cocq told him, surmising that it was animosity that accounted for the confusion surrounding the profile portrait’s existence. “Guernsey,” he remarked, “is a small place and very likely one branch of Tuppers and Brocks doesn’t get on with another branch and so on. I know that there are differences among them. I can only suppose my explanation to be true, for I do not pretend to have any certainty about it.”21 It never occurred to Colonel Robinson that someone might have been trying to suppress the profile portrait, and that Ferdinand Brock Tupper himself was the most obvious culprit.

In addition to writing Brock’s first biography, Tupper also took on the added responsibility of safeguarding his uncle’s image, which he did by keeping the two profile portraits under wraps. Conspiratorial though it might seem, Tupper had both the motive and the means. He was undoubtedly Sir Isaac Brock’s greatest admirer, and had a tendency to present his hero in the best possible light.22 As for Brock’s profile portraits, Tupper seems to have disapproved of both, possibly because they showed only one half of the noble countenance.23 Whatever Tupper’s rationale, he was evidently determined to conceal them by denying their very existence. Despite the fact that neither portrait was in his possession, he was still capable of keeping them a closely guarded secret. His status as Brock’s biographer was the key to his success. With the publication of his Family Records in 1835, and The Life and Correspondence of Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, K.B. in 1845, which was soon followed by an enlarged edition in 1847, Tupper became the contact person for anyone wanting to track down a portrait of his uncle.24 As such, he was able to intercept and deflect any request that threatened to reveal the truth. The number of times Tupper was approached is unknown, but there is a sample of what likely became his typical response. In 1861, a Canadian historian by the name of Henry J. Morgan wrote to Tupper expressing an interest in Brock’s portrait.25 Tupper replied by saying: “I cannot tell you where you can obtain a portrait of the late Sir Isaac Brock, nor am I aware of any such being in existence.”26 Yet, the original profile portrait was owned by his younger brother Henry Tupper, just as it had been for more than twenty years.27

This peculiar behaviour on the part of Ferdinand Brock Tupper became routine, and whenever someone enquired after a portrait of Sir Isaac Brock, that person invariably met with the same fate as Morgan—such as when Colonel Robinson asked on behalf of the Royal Hospital at Chelsea.28 And Dr. Hodgins might have been the next victim, except that he had the good fortune to initiate his search after Tupper’s death in December of 1873.29

At the same time that Colonel Robinson wrote to query Mrs. Henry Tupper about the disappointed officers of the 49th Regiment, he also asked how the profile portrait had come to be in her husband’s possession.30 Unfortunately, when Mrs. Le Cocq replied for her mother she could offer little in the way of provenance. She was able to report that an aged relative, a niece to Sir Isaac Brock, always remembered “seeing the two portraits in the houses of her uncles” (by which she meant to say that each uncle owned one).31 But perhaps sensing that Colonel Robinson would require something more definitive, Mrs. Le Cocq called on the assistance of her cousin.32 Miss Henrietta Tupper was knowledgeable in such matters of family history, as she was Ferdinand Brock Tupper’s daughter. But unlike her hero-worshipping father, Miss Tupper had no agenda and nothing to hide. She was happy to elaborate on the meagre provenance supplied by Mrs. Le Cocq. The profile portrait belonging to Mrs. Henry Tupper (fig. 3) was a bequest to that lady’s husband from his uncle, Irving Brock. The other one, which was thought to be a copy (fig. 4), formed part of the inheritance Mrs. Huyshe received from her father, John Savery Brock.33

Thanks to Colonel Robinson and Miss Tupper, the lieutenant governor had a much better understanding of the confusing provenance of the two profile portraits of Sir Isaac Brock. While there was no indication as to the identity of the artist responsible for either of them, it was of little consequence.34 The lieutenant governor was satisfied that the portrait copied for him by Miss Kerr-Nelson was an authentic likeness, which was all that mattered, but he could not help but dwell on the portrait owned by Mrs. Huyshe. Since she had not specified that it was a close copy of the profile portrait, the lieutenant governor was left wondering if it could yet be the kind of full-faced portrait he sought.

Once again, Colonel Robinson wrote to Mrs. Huyshe. If her portrait happened to be full-faced, then he wished to have it photographed for his brother’s consideration.35 But Mrs. Huyshe was on vacation in Malta when the colonel’s letter arrived, and so she referred it to Miss Henrietta Tupper for reply.36 In her answer to Colonel Robinson, Miss Tupper enclosed a photograph of the portrait owned by Mrs. Huyshe (fig. 4).37 Disappointingly, it too was a profile portrait and clearly a facsimile of the one owned by Mrs. Tupper. Perhaps as consolation, Miss Tupper mentioned a third likeness of Brock, “also a profile, in bronze” (fig. 8).38 This mysterious portrait was actually a bronzed silhouette, meaning a silhouette with painted highlights of gold. But as Colonel Robinson assured his brother, “it is pretty clear that we have already got the best likeness possible of Sir Isaac and that no full faced one undoubtedly is to be obtained.”39

Figure 8.

By August of 1882, Miss Kerr-Nelson’s portrait of Brock (fig. 6) arrived in Toronto.40 While there is no record of the lieutenant governor’s reaction to it, he must have been favourably impressed as it was retained and put in an elaborate gold frame.41 But, just as Colonel Robinson feared, Miss Kerr-Nelson’s artistic abilities were not deemed suitable for Government House. The lieutenant governor preferred the style of George Berthon’s portraiture, and that artist was soon commissioned to paint the official portrait of Sir Isaac Brock. Berthon worked diligently on his assignment, which appears to have been completed sometime before the end of that same year.42 Judging from the finished canvas (fig. 9) he relied almost exclusively on the photograph of the original profile portrait (fig. 3). It would seem that Miss Kerr-Nelson’s bold brush strokes, while they may have suited Brock’s character, were not compatible with Berthon’s more refined style of painting.

Figure 9.

Berthon was careful to make a faithful copy of Brock’s profile portrait, but only in terms of the facial features. In painting the rest of the portrait, he allowed himself considerable latitude. The uniform, for example, was upgraded to reflect Brock’s ultimate promotion to major general. Moreover he was shown in a dress uniform—the formality of which was more in keeping with the stately decor of Government House.43 Brock was also represented in three-quarter length, as opposed to the half-length of the original portrait, which allowed Berthon’s subject to strike a more dignified pose (albeit still in profile).

One of the official portrait’s early admirers was the Canadian historian William Kingsford, who was also one of the few people to recognize the importance of Lieutenant Governor Robinson’s Gallery of Governors. As Kingsford observed, Ontario was singularly fortunate in possessing authentic portraits of its lieutenant governors from the earliest date, “not fanciful works of art, christened [as authentic] by auctioneers and dealers.”44 Kingsford then went on to predict the rich benefits to be derived from one of the portraits in particular: “The veneration felt in Canada for the memory of the illustrious Brock, is general in every sense. His name is a household word with our youth, and it will be a matter of common satisfaction to know that the portrait we possess is genuine and undoubted.”45 It would have been more prophetic, however, had Kingsford foretold of a general apathy, as none of the portraits could have much of an impact on the public sequestered deep within Government House. As a result, Lieutenant Governor Robinson’s good deed went largely unnoticed.

Apart from Kingsford, no one else took much interest in Berthon’s portrait of Brock until 1894, when a Toronto artist suddenly asked about it. To the Honourable John Beverley Robinson (who was no longer the lieutenant governor), it might have seemed that perhaps a fitting recognition of his good deed was finally in the offing.46 But if so, it soon became obvious that John Wycliffe Lowes Forster was driven more by self-interest than by any appreciation for Robinson’s efforts in procuring Brock’s portrait.47 Having been commissioned to render his own version, Forster wanted to make use of the same reference material Berthon had utilized, including the portrait by Miss Kerr-Nelson (fig. 6).48 Robinson graciously complied with the request, no doubt because Forster’s client—like Robinson himself—hailed from one of Ontario’s old Conservative dynasties. This client was John A. Macdonell, a lawyer from eastern Ontario, a published historian, and a relative of Lieutenant Colonel John Macdonell—Brock’s courageous provincial aide-de-camp.49

Such a famous association was certainly justification enough for John A. Macdonell to commission a portrait of Brock, but there might have been another consideration as well. Soon after the portrait (fig. 10) was completed (in December of 1894) a contributor to the Week’s “Art Notes”—possibly Forster himself—apprised the paper’s readers that it was “to form the frontispiece of Mr. D[avid] B. Read’s ‘Life and Times of General Brock,’ now in press.”50 While this reference seems to suggest that the commission was undertaken to provide Read with an illustration, it is also possible that the arrangement was merely coincidental. Whatever it was that motivated Forster, the end result was nothing short of striking. One observer described the new portrait of Brock as “powerful,” in the sense that it conveyed an impression of the “great intellectual and physical features which characterized the man.”51 This assessment must have been extremely gratifying to Forster, who was known to boast about his ability to capture “the character and prevalent moods” of his sitters.52 Yet, Forster owed much of his success in this instance to Mrs. Carl Hirschberg, the former Miss Alice Kerr-Nelson, as it was her painting he had copied.53

Figure 10.

Forster’s portrait of Brock was a highly successful commission, both for its artistic merit and also for its effectiveness as a marketing tool. Thanks to the obliging nature of John A. Macdonell, the portrait was reproduced in a number of publications and even borrowed for the occasional exhibit.54 It was all good advertising—and very timely, given the potential for lucrative repeat business in the not-too-distant future. The centenary of Brock’s death was less than a decade away, and thanks to the Macdonell commission Forster was poised to capitalize on the dead general’s heroic image. But before he was able to corner the market, a couple of historically minded ladies threatened his bottom line with a new and improved portrait of Sir Isaac Brock.